Abstract

Two-dimensional (2D) metals are appealing for many emergent phenomena and have recently attracted research interests1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Unlike the widely studied 2D van der Waals (vdW) layered materials, 2D metals are extremely challenging to achieve, because they are thermodynamically unstable1,10. Here we develop a vdW squeezing method to realize diverse 2D metals (including Bi, Ga, In, Sn and Pb) at the ångström thickness limit. The achieved 2D metals are stabilized from a complete encapsulation between two MoS2 monolayers and present non-bonded interfaces, enabling access to their intrinsic properties. Transport and Raman measurements on monolayer Bi show excellent physical properties, for example, new phonon mode, enhanced electrical conductivity, notable field effect and large nonlinear Hall conductivity. Our work establishes an effective route for implementing 2D metals, alloys and other 2D non-vdW materials, potentially outlining a bright vision for a broad portfolio of emerging quantum, electronic and photonic devices.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. The datasets used for Figs. 3 and 4 and Extended Data Figs. 5, 7 and 9 are provided as Source data. All other data are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Chen, Y. et al. Two-dimensional metal nanomaterials: synthesis, properties, and applications. Chem. Rev. 118, 6409–6455 (2018).

Gou, J. et al. Two-dimensional ferroelectricity in a single-element bismuth monolayer. Nature 617, 67–72 (2023).

Briggs, N. et al. Atomically thin half-van der Waals metals enabled by confinement heteroepitaxy. Nat. Mater. 19, 637–643 (2020).

Xing, Y. et al. Quantum Griffiths singularity of superconductor-metal transition in Ga thin films. Science 350, 542–545 (2015).

Jäck, B. et al. Observation of a Majorana zero mode in a topologically protected edge channel. Science 364, 1255–1259 (2019).

Maniyara, R. A. et al. Tunable plasmons in ultrathin metal films. Nat. Photon. 13, 328–333 (2019).

Zhu, F.-f et al. Epitaxial growth of two-dimensional stanene. Nat. Mater. 14, 1020–1025 (2015).

Ji, J. et al. Two-dimensional antimonene single crystals grown by van der Waals epitaxy. Nat. Commun. 7, 13352 (2016).

Chen, L. et al. Exceptional electronic transport and quantum oscillations in thin bismuth crystals grown inside van der Waals materials. Nat. Mater. 23, 741–746 (2024).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004).

Geim, A. K. & Grigorieva, I. V. Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 499, 419–425 (2013).

Liu, Y. et al. Van der Waals heterostructures and devices. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16042 (2016).

Novoselov, K. S., Mishchenko, A., Carvalho, A. & Castro Neto, A. H. 2D materials and van der Waals heterostructures. Science 353, aac9439 (2016).

Du, L. et al. Engineering symmetry breaking in 2D layered materials. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 193–206 (2021).

Du, L. et al. Moiré photonics and optoelectronics. Science 379, eadg0014 (2023).

Rotkin, S. V. & Hess, K. Possibility of a metallic field-effect transistor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 3139–3141 (2004).

Steves, M. A. et al. Unexpected near-infrared to visible nonlinear optical properties from 2-D polar metals. Nano Lett. 20, 8312–8318 (2020).

Jin, K.-H., Oh, E., Stania, R., Liu, F. & Yeom, H. W. Enhanced Berry curvature dipole and persistent spin texture in the Bi(110) monolayer. Nano Lett. 21, 9468–9475 (2021).

Reis, F. et al. Bismuthene on a SiC substrate: a candidate for a high-temperature quantum spin Hall material. Science 357, 287–290 (2017).

Shao, Y. et al. Epitaxial growth of flat antimonene monolayer: a new honeycomb analogue of graphene. Nano Lett. 18, 2133–2139 (2018).

Fang, A. et al. Bursting at the seams: rippled monolayer bismuth on NbSe2. Sci. Adv. 4, eaaq0330 (2018).

Wu, X. et al. Epitaxial growth and air-stability of monolayer antimonene on PdTe2. Adv. Mater. 29, 1605407 (2017).

Huang, L. et al. Intercalation of metal islands and films at the interface of epitaxially grown graphene and Ru(0001) surfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 163107 (2011).

Calleja, F. et al. Spatial variation of a giant spin–orbit effect induces electron confinement in graphene on Pb islands. Nat. Phys. 11, 43–47 (2014).

Hussain, N. et al. Ultrathin Bi nanosheets with superior photoluminescence. Small 13, 1701349 (2017).

Li, L. et al. Epitaxy of wafer-scale single-crystal MoS2 monolayer via buffer layer control. Nat. Commun. 15, 1825 (2024).

Jiang, K. et al. Mechanical cleavage of non-van der Waals structures towards two-dimensional crystals. Nat. Synth. 2, 58–66 (2023).

Singh, S. et al. Low-energy phases of Bi monolayer predicted by structure search in two dimensions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 7324–7332 (2019).

Lu, Y. et al. Topological properties determined by atomic buckling in self-assembled ultrathin Bi(110). Nano Lett. 15, 80–87 (2015).

Kittel, C. & McEuen, P. Introduction to Solid State Physics (Wiley, 2018).

Sodemann, I. & Fu, L. Quantum nonlinear Hall effect induced by Berry curvature dipole in time-reversal invariant materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 216806 (2015).

Kang, K., Li, T., Sohn, E., Shan, J. & Mak, K. F. Nonlinear anomalous Hall effect in few-layer WTe2. Nat. Mater. 18, 324–328 (2019).

Ma, Q. et al. Observation of the nonlinear Hall effect under time-reversal-symmetric conditions. Nature 565, 337–342 (2019).

Wu, F. et al. Giant correlated gap and possible room-temperature correlated states in twisted bilayer MoS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 256201 (2023).

Ma, T. et al. Growth of bilayer MoTe2 single crystals with strong non-linear Hall effect. Nat. Commun. 13, 5465 (2022).

Du, L. et al. Nonlinear physics of moiré superlattices. Nat. Mater. 23, 1179–1192 (2024).

Kumar, D. et al. Room-temperature nonlinear Hall effect and wireless radiofrequency rectification in Weyl semimetal TaIrTe4. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 421–425 (2021).

Huang, M. et al. Giant nonlinear Hall effect in twisted bilayer WSe2. Natl Sci. Rev. 10, nwac232 (2022).

Lannin, J. S., Calleja, J. M. & Cardona, M. Second-order Raman scattering in the group-Vb semimetals: Bi, Sb, and As. Phys. Rev. B 12, 585–593 (1975).

Puthirath Balan, A. et al. Exfoliation of a non-van der Waals material from iron ore hematite. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 602–609 (2018).

Balan, A. P. et al. Non-van der Waals quasi-2D materials; recent advances in synthesis, emergent properties and applications. Mater. Today 58, 164–200 (2022).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank N. Lu, M. Zhu and L. Yang for their assistance with the in-plane XRD measurements. We thank X. Li for the SAED analysis and Y. Wang for the discussions. This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2021YFA1202900), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, grants 62488201, 12422402, 12274447 and 62204166), the Guangdong Major Project of Basic and Applied Basic Research (2021B0301030002) and the China National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents (no. BX20230251). L. Du acknowledges the National Key R&D Program of China (grant 2023YFA1407000).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.Z. proposed and supervised the project; J.Z. was involved in all aspects of this work, including experimental setup, sample preparations and electrical and optical characterizations with help from J.D., K.J., X.L., Z.H., J. Liu, Y.C., X.Z. and S.W.; P.L., J.P. and S.D. conducted the theoretical calculations. L. Dai took the in-plane XRD measurements; Y.W. and P.Z. prepared the fast-cooling samples; L.L., L.Z., Y.Z., H.Y., Z.W., J. Li and B.W. provided the MoS2-sapphire samples; J.Z., L. Du, W.Y. and G.Z. analysed the data with help from N.L. and D.S.; and J.Z., L. Du and G.Z. wrote the paper with the input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Fengxia Geng, Han Woong Yeom and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

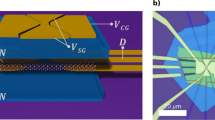

Extended Data Fig. 1 The photograph and diagram of the squeezing setup.

Note that the bottom/top plate (made of tungsten steel) can be heated up (temperature range: 20–500 °C) and exerted force (force range: 0–50000 N).

Extended Data Fig. 2 The large-scale optical image.

a, The optical microscopy images of Bi over a ~1 mm2 area produced under ~140 MPa. Those areas marked with white dashed lines are the monolayer regions; while those areas marked with brown dashed lines are the bilayer MoS2 regions without metal inside. b, Zoom-in optical images taken from the red rectangular area of (a). c, AFM images of monolayer Bi. The height line profile indicates the thickness of ~0.64 nm.

Extended Data Fig. 3

The diffraction patterns of In (a), Sn (b), and Pb (c). In addition to the diffraction spots from MoS2 (marked in red), sharp and regular diffraction spots (marked in yellow) can be recognized explicitly for In, Sn and Pb, suggesting the single crystal nature. From the diffraction patterns, we can extract that In and Sn have a rectangle lattice structure, while Pb has a hexagonal lattice structure.

Extended Data Fig. 4 The diffraction patterns taken from 56 monolayer Bi samples.

All the monolayer Bi samples show rectangle diffraction patterns and thus are α-phase.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Theoretical calculations.

a. Formation enthalpies ∆H of the selected configurations. The magnitude of the energy above hull is represented by colour, as indicated by the colour bar. b,c, The schematic diagrams of heterojunctions composed of α-Bi(110) (b) and β-Bi(111) (c). Both the formation enthalpies ∆H and the energy above convex hull for MoS2/α-Bi/MoS2 are lower than those for MoS2/β-Bi/MoS2, indicating that the α phase structure is more energy favourable and thus the ground state phase. In addition, the interlayer spacing between α-Bi and MoS2 is ~3.1 Å, which signifies the vdW stacking.

Extended Data Fig. 6 SAED patterns taken from randomly picked 20 positions across the entire Bi film.

The diffraction area is ~1 μm, and adjacent SAED patterns are taken more than 5 μm apart. It can be seen that these SAED patterns are essentially identical with a degree of rotational misalignment <1°, evidencing the single-crystalline nature of the achieved monolayer Bi.

Extended Data Fig. 7 In-plane XRD measurements.

a, XRD pattern of φ scan using Al2O3 (110), MoS2 (110), and Bi (100) Bragg condition respectively. b,c, XRD pattern of an in-plane scan around the Bi (100) Bragg condition (b) and around the Bi (010) Bragg condition (c). The 2θ angle of 35.104° ± 0.045° (37.764 ± 0.013°) indicates the lattice parameter of monolayer Bi 5.108 ± 0.006 Å (4.760 ± 0.001 Å), which matches well with the measured TEM results.

Extended Data Fig. 8 vdW squeezing experiments under the fast-cooling process.

a, The photograph of the operating apparatus for the fast-cooling process. Cryogenic nitrogen (from a liquid nitrogen tank) is aggressively blown to the sample for the fast-cooling process. In such way, the samples can cool down quickly within 10 min. b-d, The optical image, SAED pattern, atomic-resolution STEM image of the as-produced Bi under the fast-cooling process. Monolayer Bi can be reliably achieved, but with much smaller grain sizes and some grain boundaries can be clearly seen at the grain-grain jointing regions. It is noteworthy that from the atomic-resolution STEM image, the as-produced Bi under the fast-cooling process is also α-phase.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Hall measurements.

a, Antisymmetricalized Hall resistance versus the magnetic field from −9 T to 9 T. The inset is the measurement configuration. The sign of Hall voltage demonstrates the p-type behavior of 2D-Bi film. b, Carrier density extracted from Hall measurements across several samples. c, The extracted Hall mobility of monolayer Bi at 1.5 K and 42 mK from different devices. At 1.5 K (42 mK), the average Hall mobility of monolayer Bi is ~300 cm2V−1s−1 (~500 cm2V−1s−1). The extracted mean free path is ~100 nm.

Extended Data Fig. 10 vdW squeezing experiments under different pressures.

The optical microscope images of the as-produced Bi under 50 MPa (a), 80 MPa (b), 100 MPa (c), 130 MPa (d), 140 MPa (e). The scale bars are 20 μm. When the applied pressure is small, i.e., 50 MPa and 80 MPa, all Bi samples produced are thick and no monolayer Bi can be found. When the applied pressure is increased to a moderate value, i.e., 100 MPa and 120 MPa, mono-, bi-, tri-, and few-layer Bi samples can be observed simultaneously, and the probability that monolayer Bi occurs increases with increasing the applied pressure. When the applied pressure is high, i.e., 140 MPa, Bi monolayers larger than 100 μm can be obtained.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Notes, Supplementary Tables, Supplementary Figs. and Supplementary References.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, J., Li, L., Li, P. et al. Realization of 2D metals at the ångström thickness limit. Nature 639, 354–359 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08711-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08711-x

This article is cited by

-

Van der Waals injection-molded crystals

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2025)

-

Move over graphene! Scientists forge bismuthene and host of atoms-thick metals

Nature (2025)

-

Pronounced orbital-coupled asymmetrically coordinated NiCoMn heterotrimetallic atomic sites enable efficient thousand-hour urea electrooxidation-coupled hydrogen production

Nature Communications (2025)

-

General strategy for activating ferroelectricity in bilayer 2D materials with intercalating inert atoms

npj Computational Materials (2025)

-

News and views (7&8)

AAPPS Bulletin (2025)