Abstract

Addressing climate change requires accelerating the development of sustainable alternatives to energy- and water-intensive technologies, particularly for rapidly growing infrastructure such as data centres and cloud1. Here we present a life cycle assessment study examining the impacts of advanced cooling technologies on cloud infrastructure, from virtual machines to server architecture, data centre buildings and the grid. Life cycle assessment is important for early-stage design decisions, enhancing sustainability outcomes alongside feasibility and cost analysis2. We discuss constructing a life cycle assessment for a complex cloud ecosystem (including software, chips, servers and data centre buildings), analysing how different advanced cooling technologies interact with this ecosystem and evaluating each technology from a sustainability perspective to provide adoption guidelines. Life cycle assessment quantifies the benefits of advanced cooling methods, such as cold plates and immersion cooling, in reducing greenhouse gas emissions (15–21%), energy demand (15–20%) and blue water consumption (31–52%) in data centres. This comprehensive approach demonstrates the transformative potential of life cycle assessment in driving sustainable innovation across resource-intensive technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Since 2010, global internet traffic has increased more than 15-fold, with the sharpest jump occurring in the past few years. The increasing demand for cloud apps, machine learning, augmented reality, autonomous vehicles, artificial intelligence (AI) and other applications3,4,5 is driving the rapid acceleration and transfer of computing tasks to data centres, to the point that this phenomenon has been called the fourth industrial revolution. And this revolution has just begun6.

As exciting and useful as it is, the data-centre-centric revolution also poses sustainability challenges. Generally, data centres consume 10–50 times more energy per square foot than typical commercial office buildings1. Across providers, data centres accounted for approximately 1.5% (about 300 TWh) of global electricity demand in 2020, a figure that is expected to increase in the future7. It should be noted that, owing to energy efficiency improvements, the increase in data centre energy use has grown more slowly than the number of data centres and the equipment they house. Expressed as energy per compute instance, the energy intensity of global data centres has decreased by 20% annually since 2010 (ref. 7).

The information, communication and technology (ICT) sector needs to do more. The Science Based Target Initiative (SBTi) indicates that a 42% reduction by 2030 (compared with a 2015 baseline) in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions across the entire ICT sector must occur to achieve net-zero and limit global warming to 1.5 °C as recommended by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)8. To meet this challenge, the ICT sector should prioritize data centre designs that reduce consumption of water, energy and GHG emissions.

Strong action is necessary. However, without understanding the overall environmental implications of new technologies, organizations find it difficult to chart a path to their reduction goals. Microsoft has committed to being carbon-negative and water-positive by 2030 (ref. 9). As part of achieving this commitment, Microsoft has used life cycle assessment (LCA) to systematically analyse the potential environmental impacts of data centres (GHG emissions, energy and water consumption) and enable sustainability by design. When applied to the wider data centre industry, LCAs show that traditional cooling technologies can comprise up to 40% of the total energy demand of the data centre10. Microsoft has already driven a reduction in data centre cooling and power conditioning overheads with power usage effectiveness (PUE) as low as 1.12 (ref. 11). Doing more requires a better understanding of the impacts of different cooling technologies, which can be provided by LCA.

In general, any product or system at any stage in development can benefit from LCAs, but early application provides the greatest benefits2,12. Here we use LCA to analyse three cooling technologies for data centres: (1) cold plate (also referred to as direct-to-chip); (2) one-phase immersion; and (3) two-phase immersion cooling. The analysis considers the impact of these technologies on the efficiency and performance of the computational infrastructure. The LCA included raw material acquisition, production, transportation, use and EOL treatment to pre-emptively identify and mitigate the most notable data centre value chain impacts and support effective decision-making for GHG, energy and water reduction.

Data centre cooling systems, including required equipment and use cases, have been extensively reviewed13,14. However, to our knowledge, this is the first public LCA comparing the GHG emissions, energy demand and blue water consumption of air cooling, cold plate and immersion cooling completed by a hyperscale cloud provider. The LCA approach described—and the lessons learnt—can be leveraged for other energy- and water-hungry applications.

The challenges of data centre cooling

As cloud-service demands increase, so must data centre capacities and heat mitigation strategies. The information technology (IT) industry has benefited from efficiencies following Moore’s law (the number of transistors on a chip and the resulting processing power doubling every 2 years) and Dennard scaling (doubling the transistors per unit area for each new generation of semiconductors without altering their power dissipation)15. However, the recent slowing of Moore’s law and Dennard scaling means that improving chip performance now requires more power and generates more heat.

Moreover, the power (measured in watts) and heat flux (measured in watts per unit area) have been increasing for both graphics processing units (GPUs) and central processing units (CPUs). This trend will probably push the thermal loads of data centres beyond the capacity of current air-cooling technologies16,17 and cause power leakage and reduce efficiency because of the higher operating temperatures of the components. Exceeding thermal limits can increase emissions, reduce clock frequency and degrade component performance18. Excessive heat also reduces server packing density.

The cooling technology contenders

Two forms of liquid cooling—cold plate and immersion cooling—can decrease energy consumption while increasing computational efficiency and capacity19, which reduces GHG emissions and water consumption. Recent research demonstrates that these cooling methods also enable overclocking (the process of running processors at a higher speed than intended) and, therefore, the packing of more virtual machines and servers into a smaller footprint20, which offers efficiencies and cloud processing advantages.

Cold plates (also referred to as direct-to-chip cooling) are small heat exchange modules equipped with microchannels to enhance heat transfer. They are typically placed on top of high-power chips and high-density components inside the server. A coolant loop flows through the cold plate to transfer the heat of the chip outside the server. A cold-plate-system liquid-to-air heat transfer ratio ranges from 50% to 80% or more.

Immersion cooling involves fully submerging servers in dielectric fluid tanks that absorb 100% of the generated heat (Fig. 1). Dielectric fluid increases heat transfer, improves chip power and performance21, and reduces power overhead and equipment degradation (because they make fans unnecessary22). The two main types of immersion cooling are one- and two-phase, as determined by fluid type and heat transfer mode. One-phase immersion transfers heat from hardware to fluid by natural and/or forced convection. Pumps push the fluid through the servers. The fluids are usually hydrocarbon-based and sometimes fluorinated (but on a smaller scale than for two-phase immersion). Two-phase immersion transfers heat from hardware to fluid by latent heat transfer: heat boils the fluid at a lower temperature (30–50 °C), the fluid vaporizes and lofts to a condenser coil and then recondenses to a liquid. In most cases, the fluids used in two-phase immersion are fluorinated.

Schematics showing the functional differences between the cooling technologies. a, Cold-plate cooling uses a metal plate with embedded channels for coolant, such as 25% polyethylene glycol and 75% water, to directly absorb and dissipate heat from electronic components with convection23,24. b, One-phase immersion systems immerse the entire server in a tank of dielectric fluid, such as mineral oil, to remove heat with convection25. c, Two-phase immersion systems submerge servers in a dielectric fluid that boils at low temperatures, such as a refrigerant, which removes heat with the phase change23.

Each cooling technology contender has pros and cons23,24,25 (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Cold plates deploy with less disruption to existing air-cooled data centres (ACDs). However, installing them can be complex, and air cooling may still be necessary. One-phase immersion uses cheaper coolants and simpler tanks than two-phase immersion but performs less effectively at the chip level. Two-phase immersion can support very high tank power densities (+500 kW) but uses polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) that have been under legislative scrutiny and requires complex tanks. In February 2023, the European Chemicals Agency proposed restricting PFAS under the chemicals regulation of the European Union26. The proposed restrictions on more than 10,000 substances would affect immersion cooling and the manufacturing of chips, chillers, devices, plastics, fire suppressants and more. An extended discussion of the potential risks—and risk-mitigation strategies—for cooling fluids in general is included in the Methods.

Both one- and two-phase immersion methods isolate servers from airborne corrosive agents (such as humidity), lower their failure rates and increase their reliability—all of which combine to decrease the total cost of ownership and reduce embodied carbon. Scale and space do not limit immersion cooling, and Intel has demonstrated that ACDs can be retrofitted for immersion cooling22. Microsoft, Alibaba, Bitfury (LiquidStack), Riot and others have pioneered immersion-cooled data centres (ICDs) and navigated the complexities of deployment, operations and maintenance16,17. Figure 2 shows some of the early cold plates and immersion pilots of Microsoft.

a, Cold plate configurations conform to server design and functionality. The left panels show a general-purpose server cooled with air (top) or cold plates (bottom). The right panels show a GPU server cooled with air (top) and cold plates (bottom). b, One-phase immersion uses tanks (left) for submersion of servers. The right panel shows a partially submerged server. c, Two-phase immersion also relies on the immersion of servers in a tank, which relies on the boiling of a refrigerant, evident as surface turbulence in the inset.

For some time, the prevailing sentiment has been that the benefits of cold plate, one-phase and two-phase immersion could ultimately outweigh their drawbacks. We conducted this LCA to provide a quantitative comparison of the different technologies to enable design decisions that enhance sustainability outcomes for data centres and cloud infrastructure. Our findings highlight that using LCA enables informed decision-making, optimizing the sustainability of advanced cooling technologies in data centres by quantifying their environmental benefits. Specifically, LCA measures the advantages of advanced cooling methods, such as cold plates and immersion cooling, in reducing GHG emissions (15–21%), energy demand (15–20%) and blue water consumption (31–52%) in data centres.

LCA for data centre cooling

Why LCA?

LCAs drive effective design and maximize the environmental performance of a product or system2,12. Although cold-plate and immersion-cooled servers reduce energy use, understanding their full potential requires assessment of the complete picture of their GHG emissions and environmental impacts. This LCA for advanced cloud cooling technologies is the first public end-to-end (software–server–data centre impacts) LCA that compares the GHG emissions, primary energy demand and blue water consumption of ACDs, cold-plate cooled data centres and ICDs. The Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) 100-year timescale of the IPCC, excluding the biogenic carbon method, was used for quantifying GHG emissions, and it is measured in units of carbon dioxide equivalents (kgCO2e). The low heating value (or net calorific value) was used to determine the primary energy from non-renewable resources and is measured in megajoules (MJ) as a measurement of energy use from fossil resources that cannot be replenished. The blue water consumption metric captures the amount of water consumed by the system, which is the withdrawals minus any water returned to the ecosystem in a usable form.

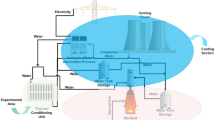

This LCA was a cradle-to-grave assessment (Fig. 3). It included the impacts of the building (core and shell), use phase workload, servers, racks (air-cooled), tanks (liquid-cooled), support equipment, grid electricity, cooling water, cooling fluids production, cold plates, CDUs and material EOL treatment of the data centre.

Impacts of all main subcomponents of the data centre were evaluated at each stage. Short descriptions of key aspects of each stage highlight the system boundaries.

Data sources and functional unit

The data analysed included equipment lists and BOM for server rack elements27, including the equipment and server differences for air-cooling, cold plate, one-phase, and two-phase immersion cooling. We calculated material environmental impact data using LCA for Experts (LCA FE) databases, ecoinvent 3.6 (refs. 28,29) and environmental product declarations (EPDs). The support equipment was primarily modelled with EPDs30,31,32,33,34.

A key challenge to LCAs for complex systems is identifying one unit for comparing systems that perform similar functions in different ways (functional unit). In this LCA, we used annualized virtual core units (Vcores). This is the smallest operational set for memory and processing capacity, and the basic unit for the cloud ecosystem. The choice of Vcores enabled data centre comparison across the entire ecosystem and was found to be an ideal comparison unit for LCAs relating to general-purpose cloud infrastructure.

Table 2 shows the individual data centre components included in the LCA model. As with many LCAs, the data limitations of this study included missing (or outdated) life cycle inventory data sources for specific equipment or semiconductors. Therefore, when necessary, we used proxies and best-available data to fill gaps. We suggest referring to the Supplementary Information, as it describes in detail how the model of this complex system was built (see Supplementary Information for detailed data sourcing and calculation information).

We estimated and modelled the use phase impacts across GHG emissions, energy and water consumption using the 2021 US energy grid average, which includes fossil fuels such as coal (22% in 2021), natural gas (38% in 2021) (ref. 35) and other sources. Both coal and natural gas contribute the most to GHG emissions and primary energy. By contrast, in 2015, thermoelectric power was the largest water consumer at 41% (ref. 36). We estimated component-specific end-of-life (EOL) impacts based on their recycled and remarketed components. Microsoft provided the primary data, and (when possible) EPDs provided secondary data. We sourced background data from LCA FE (modelling for all systems in this study was conducted in the LCA software LCA for Experts, developed by thinkstep, now Sphera (https://sphera.com/product-sustainability-software/)) and ecoinvent 3.6 when primary data or EPDs were unavailable. Microsoft has committed to sourcing 100% renewable energy for data centres, so we included this scenario in our analysis9.

We modelled fluid impacts in LCA FE for the cold-plate coolant and one-phase and two-phase cooling fluids. An immersion cooling fluid has different physical properties when compared with a cold-plate coolant. Unlike the immersion fluid, the cold plate interacts only with the chips. We assumed the cold-plate coolant to be PG25 (propylene glycol) and modelled it as a water–propylene glycol mixture (75:25). We modelled its EOL impacts as treatment of spent propylene glycol. The manufacturer modelled and provided us with the two-phase immersion fluid production and EOL impacts because they consider the fluid specifics confidential. To model the one-phase hydrocarbon fluid used in one-phase immersion fluid, we used natural gas production, liquification and fractionation into a hydrocarbon as a proxy. The one-phase immersion fluid is assumed to be re-refined, reused or repurposed, and this reuse does not cause additional impacts. The final disposal of the fluid was modelled as incineration.

LCA model

We aggregated the impacts across all life stages to represent the impact of the data centre over a 15-year lifetime, and then

-

modelled specific individual data centre components based on their lifetimes;

-

assumed a 6-year lifetime for servers (compute, networking and storage);

-

annualized support equipment based on the equipment lifetime provided by EPDs or LCAs;

-

estimated that support equipment has the same 15-year lifetime as the data centre; and

-

annualized the results based on lifetime and normalized using the total number of Vcores.

Table 3 highlights the relative differences between the key components relative to the ACD for the cold-plate cooled data centres and ICDs. Models for the data centres generated the LCA results.

Cooling technology sustainability comparison

Our LCA study has compared GHG emissions, energy demand and blue water consumption for the three cooling technologies described. In addition, we have included a parametric study to see how the different electricity sources (100% average grid energy versus 100% renewable) during the use phase affect the results. Here we present this LCA approach, challenges, successes and the lessons learnt to help other industries and sectors achieve their own sustainability goals.

The baseline results of the LCA with grid electricity showed that cold-plate technology, one-phase immersion cooling and two-phase immersion cooling for GHG emissions, energy demand and blue water consumption can save ≥15%, 15% and 31%, respectively (Table 4). A more detailed graphical breakdown of the results can be seen in Fig. 4.

Two scenarios are presented for all cooling technologies—one uses grid electricity for the operation of the data centre and the other uses renewable energy for the operation of the data centre. The results for all technologies are in reference to the total impact of ACDs using 100% grid electricity, that is, the total impact of an ACD with 100% grid electricity is always at 100, and all other results are relative to this value.

When comparing data centre designs in terms of building, cooling overhead, server architecture, overclocking and increased server lifetime, the primary environmental impact reduction driver is energy savings during the use phase and the expanded server lifetime. As shown in Fig. 4, the largest contributor to impacts for all cooling technologies is the use phase, which is consistent with other data centre LCA literature37. The electricity consumed to operate the servers in the data centre drives GHG emissions, energy demand and blue water consumption. Average grid electricity is still heavily dependent on fossil fuels (which generate GHG emissions). It is also important to note that thermal power generation (using coal and natural gas) requires water to convert to steam that turns power plant turbines. The second largest contributor to impacts comes from embodied carbon in the manufacturing of servers. Although the per-server impacts are similar between technologies, cold-plate and ICDs can hold more servers than those that are air-cooled, because liquid cooling enables higher IT capacity. Cold-plate and immersion technologies can also host higher Vcores because of better heat transfer capability when compared with air-cooling. Focusing on alternative technologies, cold plate can host more Vcores than one-phase immersion because of its higher cooling ability at the chip. This combination of effects leads to a lower server embodied carbon impact (per Vcore) for cold plates, when compared with one-phase immersion.

Building size reductions did not markedly contribute to the environmental impact reductions of cold plate or immersion cooling. Fluid impacts for two-phase and cold plate are driven by using cooling liquids and coolants, respectively. Coolant impacts are lower than two-phase fluid impacts because less coolant is used. LCA data for cooling fluids were not readily available, so we used an approximation for one-phase based on expert opinion from Microsoft and data for two-phase provided by fluid manufacturers. Cold-plate technology that uses a water–propylene glycol mix (PG25) requires less fluid per rack than immersion. One-phase immersion uses hydrocarbon, whereas two-phase immersion uses fluorinated fluids; however, in both cases, more fluid is needed than cold plates because the server must be completely immersed. Overall, the embodied carbon impacts of the cooling fluid for the three technologies are low compared with other components. LCA FE cannot accurately model one-phase fluid production, so we used the closest match between the ‘body of materials’ and the data available in the database (Methods). However, better data are needed for an accurate representation of one-phase fluid embodied impacts. For the cold-plate coolant PG25, we modelled the fluid using propylene and glycol data, but could not include additives such as corrosion inhibitors and biofilm resistors because of a lack of data. Further optimizations for cold-plate and one-phase immersion cooling that would put them on par with two-phase immersion are possible. Technology choice, thus, depends on regulatory requirements, implementation cost, environmental savings goals and deployment complexity. An example is the lower dependence of immersion cooling on water. This characteristic is particularly important in water-stressed regions.

Impact of using 100% renewable energy

According to the International Energy Agency, the contribution of renewable energy to energy generation has increased globally from 20% in 2010 to 29% in 2020 (ref. 38). This increase is significant, but an even higher decarbonization of the electric grid is necessary to keep global warming below 1.5 °C (ref. 39).

Microsoft has committed to power all its data centres and facilities with 100% additional, new renewable energy generation that matches its electricity consumption on an annual basis by 2025. By 2030, Microsoft has committed that 100% of its energy supply, 100% of the time, will come from carbon-free resources40. Therefore, 100% renewable energy in data centres was a key scenario for this study.

When a data centre is operated on 100% renewable energy, the new savings compared with air cooling for cold-plate, one-phase immersion and two-phase immersion cooling for GHG emissions, energy and blue water consumption were ≥13%, 15% and 50%, respectively (Fig. 4). In the original US average grid results, the overall GHG savings for one-phase immersion was slightly higher than cold plate although overclocking was higher for cold plate, because of the combined effects of lower server power and lower PUE for one-phase immersion that enabled more server count. When we switched the source of energy to renewable, overclocking became more dominant, because it increases the core count with reduced energy overhead (and GHG overhead). This is why in a renewable case, cold plate had lower GHG emissions. The water savings were higher because of the lower water consumption of renewable electricity.

We next focused on the impact of switching from US average grid to 100% renewable. We normalized each liquid-cooling technology to air cooling and then compared the delta between the two different sources of energy (Fig. 4). The shift from 100% grid electricity to 100% renewable energy reduced GHG emissions by 85–90%, energy demand by 6–7% and blue water consumption by 55–85%, based on the cooling technology deployed in the data centre.

Notably, the contribution from embodied carbon in servers (manufacturing overhead) became more significant under the renewable energy scenario—this highlights the need for improved and relevant data on server components for additional decarbonization41. Building-water impacts do not substantially change between air, cold-plate and immersion cooling because construction metals are primarily responsible for the embodied water impacts of the building. However, the recyclability of metals does offer a positive water impact at EOL. Overall, the embodied water impacts between air cooling, immersion cooling and cold plate are within 1–15% of each other.

A data quality assessment was performed using a pedigree matrix to help understand the quality of the input data collected and the datasets used. This pedigree matrix provides an indication of the level of variability in the data. Given that the standard deviations for datasets were not readily available, a quantitative uncertainty assessment would provide incomplete information. From this perspective, the pedigree matrix provides the necessary indication of where uncertainty could be reduced, providing future opportunities to increase data availability. The detailed pedigree matrix is provided in the Supplementary Information in the LCA Tool Excel.

LCAs to inform engineering design

Our LCA has shown that reducing data centre energy use through advanced liquid-cooling technologies will lead to marked reductions in data centre environmental impacts. This is valuable and actionable information.

Comparative LCAs, such as the one presented in this study, enable the cloud industry to focus environmental strategies on the most notable impacts of their data centre. As the ICT industry continues developing and implementing new technologies and pioneering design processes to catalyse global data centre evolution, it must prioritize environmental assessment at the same level as cost and performance. LCAs are a powerful tool that enables assessment and provides opportunities to engage internal and external stakeholders who have a strong influence over the overall environmental footprint of the ICT industry. LCAs also ensure a harmonized approach to advancing potentially sustainable technologies and facilitating decision-making.

LCAs can show the sustainability trade-offs either within the same cooling technology or when comparing different technologies against each other. For example, cold-plate cooling offers improved heat transfer at the chip compared with one-phase immersion, but may not have as low PUE values. Two-phase immersion could have high heat transfer at the chip and lower PUE at the data centre side, but might involve more complex components with higher embodied carbon toll, such as a more intricate tank design and fluid manufacturing. LCA ensures that all these engineering design decisions and trade-offs can be considered within holistic sustainability perspectives.

There are pros for each technology considered. With air-cooling, there are no required retrofits and new embodied carbon. For cold plate, less fluid is needed per rack. One-phase immersion cooling can use a variety of dielectric fluids, including synthetic hydrocarbons and fluorinated fluids—the most common being hydrocarbon-based mineral oils. One-phase immersion fluids have low global warming potential42, and the technology is relatively inexpensive. Most two-phase immersion fluids are fluorine-based dielectric and have a heat rejection capacity multiple times higher than traditional air cooling43.

There are also cons for each type of liquid cooling. Air cooling uses by far the most electricity. The copper components of a cold-plate cooling network must be replaced for each server during each IT cycle. Although hydrocarbon oils used in one-phase immersion cooling are recognized for their dielectric properties, low toxicity and low fluid loss, their high flammability is a safety concern, and their high viscosity creates pumping difficulties. Hydrocarbon oils can leave oily residues, known as oil blooms, around the immersive tanks and neighbouring surfaces, inhibiting IT maintenance43. Oil blooms can form on outside surfaces and leak to surrounding surfaces. Hydrocarbon oils are used in various fields, so established mitigation and clean-up procedures are already in place. Hydrocarbon oil spill risks include aspiration, bioaccumulation and groundwater contamination; however, engineering controls, such as triple containment, can help prevent leaks or spills. In the event of a total fluid loss to the ground, clean-up procedures typically involve replacing contaminated soil with off-site soil to eliminate groundwater leakage effects. Two-phase immersion fluids are PFAS, which face legislative restrictions for reasons mentioned earlier in the paper and in the Methods.

Each cooling technology assessed in this study has drawbacks, which could include pending regulations, additional necessary cooling infrastructure and new service and operational models. When selecting a cooling technology fluid, data centre designers should consider a wide range of criteria, including the following:

-

EHS: full environmental, health and safety analysis should be the first step when evaluating a new cooling fluid for both short- and long-term human effects, if any.

-

End-to-end LCA impacts: analysing the full data centre ecosystem to include systems interactions across software, chip, server, rack, tank and cooling fluids allows decision makers to understand where savings in environmental impacts can be made across various impact categories.

-

High cooling capability at the chip level: some fluids are capable of cooling at the chip that can result in higher efficiency and more functional units per unit resource.

-

Associated socioeconomic and business impacts: including regulatory landscape and impacts on community, short and long term, from the fluid factory to the EOL.

-

Ozone depletion potential, global warming potential: only fluids with low to zero values should be considered.

-

Bioaccumulation, aquatic and terrestrial toxicity, persistence and breakdown: in addition to taking mitigation actions to prevent leakage or spills, fluids should have minimal bioaccumulation, persistence and toxicity.

-

Viscosity, flammability and volatility: higher viscosity can lead to lower heat transfer at the chip, higher flash point to none is favourable and volatility can provide a clean service model but increase fluid loss.

LCAs can help inform regulation and policy by enabling the evaluation of trade-offs.

As shown in this LCA, all immersion cooling and cold-plate cooling technologies offer efficient cooling and heat rejection. But all available immersion fluid options have their challenges, including regulatory ones. An important application of LCA should be in the design of regulatory approaches. This is important because of emerging PFAS regulations in the European Union and the United States, which will restrict its use for two-phase immersion cooling (and a wider range of industries and products, including firefighting, medicine and food packaging).

The chemical properties and the regulatory landscape for cooling fluids used in the different technologies are further discussed in the Methods.

Conclusions

This study describes the use of LCA as a tool to compare ACDs to cold-plate data centres and ICDs. Our results demonstrate the importance of using LCA in early-stage design decisions to improve sustainability outcomes44 and show how cold-plate and immersion cooling have excellent potential for reducing environmental impacts such as GHG emissions (at least 15% reduction), energy consumption (at least 15% reduction) and water consumption (at least 31% reduction) per Vcore per year.

Our analysis has provided quantitative evidence of the sustainability aspects of relevant cooling technologies so they can be properly evaluated in decision-making: highly optimized cold-plate or one-phase immersion cooling technologies can perform on par with two-phase immersion (which has challenges because of emerging regulatory constraints on PFAS), making all three liquid-cooling technologies desirable options. Additional considerations for decision-making on cooling technologies are time-to-market, regulatory and supply chain landscapes, technology complexities and implementation costs.

A key result from our study was the effectiveness of the virtual core concept—a new approach towards a functional unit that can simplify and improve LCA analysis and comparison for complex cloud ecosystems. This can be illustrated as follows. Typically, a data centre is capable of handling millions of Vcores. If, for example, a 10 GW of IT capacity data centre can handle 1 thousand million Vcores and each Vcore in the ACD has an impact of 1 kgCO2e, 1 MJ and 1 l, the total impact of the data centre is 1 thousand million kgCO2e, 1 thousand million MJ and 1 thousand million l of water. If the same capacity centre were operated using any of the liquid-cooling technologies presented here, then the impacts of the data centre would reduce to 0.85 thousand million kgCO2e, 0.85 thousand million MJ and 0.69 thousand million l of water at the very least.

Perspective on future work

Microsoft is using these results to drive cooling and cloud infrastructure innovation. As shown here, the early use of LCA identified the embodied impacts of electronic equipment and how addressing use phase energy and shifting to renewables can reduce them. This enables Microsoft and others to effectively engage with suppliers to reduce the environmental footprint of their equipment.

Limited data availability, particularly for cooling fluids production, data-centre-specific equipment and electronics life cycles, is a constraint in the effectiveness of any LCA. Therefore, we encourage the improvement and development of more comprehensive information databases to support the increasing use and effectiveness of LCAs.

As part of its progress towards achieving its carbon-negative, water-positive commitments, Microsoft is integrating LCAs into its decision-making and data centre design processes. We hope this study will provide useful guidance and learnings to other companies and industries, large and small, to further accelerate and progress their own sustainability commitments, helping to address the unfolding global climate challenges. We have also summarized the process and lessons learnt for building LCA for cloud systems45 to facilitate others to build on top and use this approach. This foundational work will serve as a living tool that is iteratively improved based on new developments in data centre cooling, usage patterns (for example, AI training) and innovative methods to reuse waste heat (for example, warming local homes46).

Methods

Methodology and background

The LCA method used in this study compares the environmental impacts of cold-plate-cooled data centres (CPD) and ICDs with those of ACDs. Immersion cooling included both one-phase (1P-ICD) and two-phase cooling (2P-ICD). This cradle-to-grave study (Fig. 3) characterizes the GHG emissions, primary energy and blue water consumption of the CPD, 1P-ICD, 2P-ICD and ACD by analysing the infrastructure components listed in Table 2. The IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) 100-year timescale, excluding the biogenic carbon method, was used for quantifying GHG emissions. It is measured in units of carbon dioxide equivalents (kgCO2e). Biogenic carbon emissions originate from natural carbon-cycle-related biological sources, such as plants, trees and soil; therefore, excluding biogenic carbon emissions quantifies GHG emissions from fossil sources. Although biogenic carbon is part of the natural cycle, fossil-derived carbon releases otherwise sequestered carbon to the atmosphere. The low heating value (or net calorific value) was used to determine the primary energy from non-renewable resources and is measured in megajoules (MJ) as a measurement of energy use from fossil resources that cannot be replenished. The blue water consumption metric captures the amount of water consumed by the system, which is the withdrawals less any water returned to the ecosystem in a usable form. The study models the production, use phase and EOL of all components over the lifetime of the data centre.

We estimated the use phase as the energy consumed by the data centre and modelled it based on the electricity consumed by the data centre from the 2021 US grid. The US electric grid is powered by fossil fuels, namely, coal (22% in 2021) and natural gas (38% in 2021) (ref. 35), which contribute the most to GHG emissions and primary energy demand. In 2015, thermoelectric power was the largest consumer of water at 41% (ref. 36). We estimated the EOL impacts for the previously mentioned components based on the extent of recycled components. Primary data are from Microsoft, and secondary data are from EPDs wherever possible. We used LCA FE and ecoinvent 3.6 data when primary or EPD data were unavailable.

Data centres provide cloud services delivered on demand over the internet. Services include everyday applications such as Microsoft 365, storage server space infrastructure and web-based environments of the cloud apps. These services are performed in the cloud and require specific levels of memory and processing. The smallest set of operations over a given amount of memory and processing capacity is known as a virtual core (Vcore). This study used the common functional unit of 1 Vcore to analyse all cooling technologies studied because it is the fundamental unit that represents the operations carried out to provide the different cloud services. A server Vcore results from the relationship between physical cores, logical cores and packing density. A physical core (also processing units) or just simply a core is a well-partitioned piece of logic capable of independently performing all functions of a processor, that is, the CPU in the case of a general-purpose microprocessor. A single physical core may correspond to one or more logical cores. Logical cores are the number of physical cores times the number of threads that can run on each core. Packing density is the number of devices (such as logic circuits) or integrated circuits per unit area of a silicon chip.

where a is packing density 0 < a < 1.5.

The impacts across all these stages are then aggregated to represent the impact of the data centre over its 15-year lifetime. Some individual components in the data centre were modelled based on the lifetime provided by Microsoft or specified in the documentation. For servers (compute, networking and storage), we assumed a 6-year lifetime based on expert opinion from Microsoft. We annualized support equipment based on the equipment lifetime provided in the EPDs or LCAs. Any support equipment modelled in LCA FE, using data from the ecoinvent 3.6 or LCA FE databases, is assumed to have the same lifetime as the data centre, that is, 15 years. We annualized the results using the lifetime and then normalized using the total number of Vcores.

The following are explanations of the parts of the data centre and how they were modelled. Table 3 shows the relative difference in the number of components between the cold-plate cooled, immersion-cooled and ACDs.

Building production and EOL

The building shell was modelled based on the bills of material (BOM) of Microsoft and Tally. Modelling for building GHG emissions and energy was conducted using the LCA software Tally Environmental Impact Tool (https://choosetally.com/overview/). Environmental Impact Tool was used to model the GHG emissions and the primary energy demand associated with the building shell, whereas blue water consumption was modelled in LCA FE based on materials used to make the data centre. The concrete associated with the pathways and floor slabs around air-cooled, cold-plate, one-phase immersion and 2P-ICDs were included in the model. We assumed that the concrete was 5,000 psi and of an average depth of 8 in. The databases used to model the building materials were ecoinvent 3.6 and LCA FE. The analysis excluded any interior non-structural partitions, ceilings and equipment.

EOL GHG emissions and water impacts were also modelled in Tally based on building materials. Water EOL impacts were modelled in LCA FE based on building materials. For water EOL impacts, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) data were used for metal recycling and landfill rates. All other materials were assumed to be landfilled.

Server production and EOL

The compute, network and storage server models were built in LCA FE. The compute, networking and storage servers contribute 70%, 10% and 20% to the data centre IT capacity, respectively. The compute server model was built based on the BOM provided by Microsoft. The compute server includes a processor, memory module, solid-state drives (SSDs), chassis, field-programmable gate array (FPGA), assembly, riser card, heat sinks, clips, inserts and cables. The storage servers consist of just a bunch of drives (JBOD) and head nodes. The JBOD consists of processors, hard disk drive (HDD), SSD, chassis, FPGA and motherboard. Each head node is the same as that of a compute server. Owing to data gaps, the network server is assumed to be equivalent to 1.3 times the embodied impacts of a compute server, based on internal expertise.

All server types were modelled as the same between the ACDs, cold-plate data centres and ICDs, except that the cold-plate servers included copper plates, tubing, manifold and CDUs, whereas the immersion-cooled servers had no heat removal devices. The immersion-cooled servers were modelled as air-cooled servers without fans, heat sinks or baffles. The embodied impacts of the air-cooled rack were scaled based on the number of servers.

The BOM consisted of electronic and non-electronic elements (structural elements of the server). The production of electronic elements was modelled using the LCA FE electronics extension database (for example, for resistors, transistors, capacitors, printed wiring board and IC). When an exact match for an electronic component was unavailable, we identified proxies and scaled based on the package type of the component and the die area. All electronics impacts in LCA FE are based on research that changed the industry48. It is important to note that this research is two decades old, and it is crucial to have newer data for electronics to reflect current technologies. The non-electronics elements were modelled based on the material type and weight of the component. For example, if there was a steel sheet for the enclosure, then the enclosure was modelled using the steel weight. The server memory was modelled using an ecoinvent memory dataset, because a datasheet for the memory was not publicly available. The SSDs were conservatively modelled as a 16-layer printed circuit board (PCB) of a specific dimension, a silicon wafer and dynamic random-access memory (DRAM). The wafer was estimated as one-third the area of the PCB, and the remaining two-thirds was the DRAM.

The EOL of all servers is modelled as 100% recycling. All server components are assumed to be recycled after 6 years. The electronics components are modelled as the recovery of precious metals, whereas the non-electronic components are modelled as material recycling. All EOL models were weight-based for each component.

Rack and tank production and EOL

The rack or server rack cabinet in an ACD and cold plate data centre houses and organizes all the important IT systems, including servers required to provide cloud and data services. The rack is enclosed to ensure the safety and security of the server. The tank performs the same function as a rack in the ICDs, but includes cooling fluid. All IT equipment is immersed in the fluid, which removes the need for fan-based cooling. The racks and tanks are assumed to have the same lifetime as the building, which is 15 years.

The production of the rack and tank was based on the material used to construct the rack and tank. Microsoft suppliers obtained raw material type and weight data for both the rack and the tank. The power distribution unit (PDU) and the power and management distribution unit are excluded from the rack and tank because no data were available for the ICDs. The assembly and testing energy for integrating the rack and tank with the servers is also accounted for (values provided by Microsoft). Because the production of racks and tanks was modelled primarily based on input metal components, the EOL impacts were calculated based on 100% recycling of these input metals.

Support equipment production and EOL

Support equipment within the data centre consists of the mechanical and electrical equipment required for cooling and power. Support equipment was primarily modelled using EPDs and LCAs from equipment lists and BOM provided by Microsoft. If no EPDs or LCAs were available, secondary data from LCA FE was used. Support equipment modelled in an ACD and CPD included AHUs, generators, uninterrupted power supplies (UPSs), transformers, PDUs, bus ducts, bus plugs and e-houses. Support equipment modelled in the ICDs included AHUs, generators, UPSs, transformers, PDUs and adiabatic coolers. Equipment was scaled by capacity (for example, cubic feet per minute, kilovolt-amperes and kilowatts). Several EPDs or LCAs included water use rather than water consumption. In those cases, water use was used. If no water data were available within an EPD or LCA, water data were proxied using data from LCA FE. If no data were found for a piece of equipment, the closest material or component proxies available were used to estimate the impacts. The following proxies were used because of a lack of data:

-

Adiabatic cooler: proxied with a chiller and radiator.

-

e-house: proxied with the weight of steel based on product dimensions.

-

Bus ducts: proxied with copper.

EOL impacts were modelled using data from the EPDs or LCAs. If no EOL information was provided, EOL impacts were estimated using the weight of component materials. EPA data were used for metal recycling and landfill rates. Transformer oil was treated as hazardous waste, and all other waste was considered wood products or inert material and landfilled.

Use phase

Use phase energy includes the electricity consumed to operate IT and non-IT equipment at a data centre. The annual use phase energy consumption was calculated based on the IT capacity of the data centre, its average PUE and the server use rate of the data centre (also referred to as load factor).

At a data centre scale, the IT capacity is the capacity of the IT for which the data centre is built and is expressed in MW. The PUE is a ratio that describes how efficiently a data centre uses energy, and it gives the ratio of the total amount of energy used by the entire data centre to the energy delivered to the IT equipment. Finally, the load factor or operational capacity factor is the percentage of IT capacity that a specific data centre uses. The annual energy is modelled for the design capacity using a conservative assumption for the utilization rate. This conservative assumption helps in determining the capacity planning and the total number of servers and supporting equipment in the data centre.

Blue water consumption refers to surface and groundwater that the data centre uses during operation, including water use for cooling, irrigation, restrooms and cafés. Non-cooling water use (that is, restrooms, cafés and irrigation) was excluded from this analysis as it was assumed to be the same for ACDs, cold-plate-cooled data centres and ICDs because similar staffing requirements are anticipated for all types of data centre. Temperature-based use scenarios were modelled for air-cooled, cold plate-cooled and immersion-cooled scenarios. Two data centre locations in which temperatures can rise above a certain threshold were chosen to illustrate the differences in water required for cooling in a dry and a humid climate. When the temperature breaches the threshold, additional cooling may be required.

Cold-plate-cooled, immersion-cooled and air-cooled models all use air-handling units (AHUs) with evaporative cooling to provide cooling for the server rooms. Apart from AHUs for the server rooms, the cold-plate design includes copper tubing and CDUs, whereas the immersion-cooled model uses fluid coolers to reject server heat by a heat transfer fluid. In most climates, the fluid coolers can provide sufficient cooling without water (dry operation). However, in some environments, additional cooling capacity is required for parts of the year, in which case adiabatic cooling (wet operation) is used. Adiabatic systems pre-cool warm outdoor air with water when the outdoor air is above a user-specified temperature, taking advantage of the temperature decrease when water changes phases from liquid to vapour20,49. Adiabatic systems use more water to cool but have higher cooling efficiency than dry cooling systems, especially in warm, dry climates50. In this analysis, it was assumed that when the outdoor dry-bulb temperature is above 35 °C, the adiabatic cooling capacity of the fluid coolers is enabled. The dry-bulb temperature, or ambient temperature, is the air temperature measured by a thermometer not affected by the moisture of the air (https://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/dry-wet-bulb-dew-point-air-d_682.html). Fewer air-handling units and adiabatic coolers result in less water use for cooling in ICDs. A key metric for water use is cycles of concentration, a measure of the concentration of dissolved solids in the cooling tower process water. As water evaporates from a cooling tower, it leaves behind dissolved solids, which increase in concentration in the process water until there is a blow-down (flushing the system to prevent the buildup of solids). As the dissolved solids increase, so do the cycles of concentration (https://aquaclearllc.com/technical-info/cooling-tower-cycles-of-concentration-and-efficiency/). Higher cycles of concentration mean more fresh make-up water is required, resulting in greater overall water use.

Design assumptions for cooling technologies

Cold-plate technology is a functional hybrid of air-cooling and two-phase immersion cooling technologies. At the chip level, it has cooling ability similar to two-phase cooling, but at the data centre level, it could have a higher PUE than two-phase cooling because it still requires air cooling. Cold-plate technology uses racks, so the design for cold plates uses racks with the same power as two-phase immersion tanks. The compute server power for cold-plate technology is the average of the power of air-cooled and two-phase immersion servers. The PUE is also an average of the air-cooled and two-phase immersion PUE. To account for the cold-plate copper, tubing, manifolds and CDUs, the cold-plate embodied rack impacts were scaled by a suitable factor to be equivalent to the embodied impacts of one cold-plate rack, including the copper, tubing, manifolds and CDUs. Cold-plate cooling typically uses water or a water–propylene glycol mixture as the cooling fluid. For the model, the coolant PG25 was modelled using a water–propylene glycol mixture (75:25). EOL impacts were modelled as the treatment of a spent water–glycol mixture.

The one-phase immersion cooling has the same tank power, same compute server power, compute server count, data centre architecture, data centre footprint and PUE as the two-phase immersion cooling design. The fluid used in one-phase immersion cooling is different from the two-phase immersion fluid. The one-phase immersion fluid is modelled as a hydrocarbon derived from natural gas. To model the fluid, natural gas is produced and then converted to liquefied natural gas. Finally, the liquified natural gas is fractionated into hydrocarbons. After the useful lifetime of the one-phase immersion fluid, the fluid is assumed to be re-refined and reused or repurposed. EOL impacts after cycles of reuse and repurposing were modelled as incineration. The fluid quantity used for one-phase is the same as for two-phase, but the heat removal efficiency of the one-phase fluid is lower than that of the two-phase fluid, so the overclocking rate under the best-case scenario for one-phase immersion is capped at 10%. The tank embodied impacts for the one-phase fluid are the same as those for two-phase immersion cooling because the one-phase immersion tank has a higher number of CDUs, although the tank itself is simpler.

The two-phase immersion fluid and EOL impacts were modelled by the manufacturer and remain confidential.

Data quality assessment

A quantitative uncertainty assessment is not possible across all the datasets that are used, in part because standard deviation is not accounted for in most of the datasets available for LCA FE. Instead, a pedigree matrix was developed to qualitatively assess the data quality, which in turn provides an indication of variability and uncertainty in the model.

The quality of fit, or representativeness, of model inputs was evaluated across five indicator categories: reliability, completeness, temporal correlation, geographical correlation and technological correlation, as shown Extended Data Table 1. For each indicator, a score of 1–5 was assigned to each model input, where 1 indicates high representativeness of the product system and 5 indicates low representativeness51. The assessment was completed across life cycle stages for a final average score in each indicator.

Geographical resolutions have seven levels: global, continental, sub-region, national, province/state/region, county/city and site-specific51. The sub-region level refers to regional descriptions (for example, the United Arab Emirates), and the site-specific level, the most granular level, and includes the physical address of the site. The geographical correlation is scored based on the level of the input data and the level of the dataset that is available.

Technological correlation is represented using four categories: process design, operational conditions, material quality and scalability. Process design refers to the set of conditions in a process that affect the product. Operational conditions refer to variable parameters such as heat, temperature and pressure that are needed to make the product. Material quality refers to the type and quality of feedstock material. Scale refers to output per unit time or per line that needs to be described.

As described in the Supplementary Information, the data quality across all the phases that were modelled is between good and average. They scored between 2 and 3 across all data quality categories. Overall, the assessment has a score of 3 for data quality, which indicates that the variability in data is not large and is manageable. A key reason for this is the large impact that the use phase has on all three impact categories. The data quality for the use phase has consistently been high, and hence has had low uncertainty; the uncertainty of the overall results is also low.

PFAS: LCAs to inform sustainability regulations

As shown in this LCA, immersion cooling offers the most efficient cooling and heat rejection; however, all available fluid options have their challenges, including regulatory ones. An important application of LCAs should be in the design of regulatory approaches. This is important because of emerging PFAS regulations in the European Union and the United States, which will restrict its use for two-phase immersion cooling (and a wider range of industries and products, including firefighting, medicine and food packaging).

The chemical properties and the regulatory landscape for cooling fluids used in the different technologies are further discussed in this section.

Fluids that are important for two-phase immersion cooling are classified as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and more than 4,000 synthetic chemicals are used in industries and products such as firefighting, medicine and food packaging. Emerging PFAS regulations in the European Union and the United States are a potential barrier to their use in two-phase immersion cooling. On 7 February 2023, the European Chemicals Agency published the restriction proposal for PFAS substances26. Similarly, several US states are also working to restrict or ban non-essential PFAS use. A broad ban on more than 10,000 chemicals might be impractical, but science-based regulations based on overall LCA, persistence, bioaccumulation and toxicity may be effective.

The limitations on PFAS use may directly influence data centre immersion-cooling efforts. However, LCAs can calculate PFAS leakage impacts, help mitigate their associated risks and establish industry best practices such as sealed tanks and multiple levels of fluid containment.

For end users, LCAs are powerful tools in reducing GHG emissions, water consumption and energy demand. A holistic, multi-pronged risk-mitigation approach to use liquid-cooling fluids at scale includes the following:

-

alleviating the impacts of accidental spills by using chemicals that will not partition into groundwater and have lower solubility and reactivity with water streams;

-

ensuring that the fluid creation process follows all environmental, health and safety protocols, and that the production plant always acts as a good neighbour to its surrounding community;

-

tracking transportation and establishing the shortest possible routes;

-

using containers and secondary containers to prevent direct ground spills;

-

situating the data centres away from large bodies of water (above or below ground) in zones with low natural disaster risk and drier climates;

-

using asphalt and concrete barriers to catalyse evaporation if spill prevention fails; and

-

minimizing server and tank fluid usage, designing tanks for minimal fluid loss, implementing primary and secondary spill containment, monitoring vapour loss, implementing mechanical and chemical vapour traps at the exhaust systems and providing adequate air circulation in the data centre.

Data availability

The datasets and tools generated and/or analysed during the current study are available at Zenodo52 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14268168). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Data centers and servers. US Department of Energy https://www.energy.gov/eere/buildings/data-centers-and-servers (2022).

ISO. ISO 14040:2006 Environmental Management — Life Cycle Assessment — Principles and Framework (ISO, 2006).

Data centers and data transmission networks. IEA https://www.iea.org/energy-system/buildings/data-centres-and-data-transmission-networks (2021).

Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index. Digiconomist https://digiconomist.net/bitcoin-energy-consumption (2022).

Gallersdörfer, U., Klaaßen, L. & Stoll, C. Energy consumption of cryptocurrencies beyond Bitcoin. Joule 4, 1843–1846 (2020).

Maynard, K. & Ross, P. Towards a 4th industrial revolution. Intell. Build. Int. 13, 159–161 (2021). no. 3.

Masanet, E., Shehabi, A., Lei, N., Smith, S. & Koomey, J. Recalibrating global data center energy-use estimates. Science 367, 984–986 (2020).

IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2018).

2022 Environmental Sustainability Report. Microsoft https://query.prod.cms.rt.microsoft.com/cms/api/am/binary/RW13Fpq (2023).

Whitehead, B. et al. The environmental burden of data centres - a screening LCA methodology. In CIBSE ASHRAE Technical Symposium (2012).

Inside Azure Innovations with Mark Russinovich. Microsoft. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PO5ijv6WDv0 (2023).

ISO. ISO 14044:2006. ISO, Environmental Management — Life Cycle Assessment — Requirements and Guidelines (ISO, 2006).

Khalaj, A. H. & Halgamuge, S. K. A review on efficient thermal management of air- and liquid-cooled data centers: from chip to the cooling system. Appl. Energy 205, 1165–1188 (2017).

Xu, S., Zhang, H. & Wang, Z. Thermal management and energy consumption in air, liquid, and free cooling systems for data centers: a review. Energies 16, 1279 (2023).

Johnsson, L. & Netzer, G. The impact of Moore’s law and loss of Dennard scaling: are DSP SoCs an energy efficient alternative to x86 SoCs? J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 762, 012022 (2016).

Jalili, M. et al. Cost-efficient overclocking in immersion-cooled datacenters. In 2021 ACM/IEEE 48th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA) 623–636 (IEEE, 2021).

Ramakrishnan, B. et al. CPU overclocking: a performance assessment of air, cold plates, and two-phase immersion cooling. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packaging Manuf. Technol. 11, 1703–1715 (2021).

Raniwala, A. Bringing 2-phase immersion cooling to hyperscale cloud. In Optical Fiber Communication Conference (OFC) Technical Digest Series (Optica, 2022).

CoolIT liquid cooling solutions contribute towards sustainability and energy efficiency in data centers. Bloomberg Business (20 January 2023).

Jones, N. How to stop data centres from gobbling up the world’s electricity. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-06610-y (12 September 2018).

Kanbur, B. B., Wu, C., Fan, S., Tong, W. & Duan, F. “Two-phase liquid-immersion data center cooling system: Experimental performance and thermoeconomic analysis. Int. J. Refrig. 118, 290–301 (2020).

Avalos, J., del Rio, O. & Farias, O. Air cooling server conversion to two phase immersion cooling and thermal performance results. In 2022 38th Semiconductor Thermal Measurement, Modeling and Management Symposium (SEMI-THERM) 55–61 (IEEE, 2022).

Alissa, H. & Rubenstein, B. OCPSummit19 - EW: Advanced Cooling - Liquid Cooling Trends and Requirements for Racks and Servers. Open Compute Project Global Summit. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=108r5nOcElw (2019).

Alissa, H. & Rubenstein, B. Liquid Cooling Trends (Open Community, 2019).

Chiaroni, D., Amalfi, R., George, J. & Riegel, M. Towards greener digital infrastructures for ICT and vertical markets. Ann. Telecommun. 2023, 255–275 (2023).

European Chemicals Agency. Annex XV Restriction Report - Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): Proposal for a restriction (European Chemicals Agency, 2023).

Boyd, S. B. Life Cycle Assessment of Semiconductors (Springer, 2012).

Wernet, G. et al. The ecoinvent database version 3 (part I): overview and methodology. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 21, 1218–1230 (2016).

Sphera. Dataset Documentation. https://lcadatabase.sphera.com/dataset-documentation-download/ (2023).

ABB Oy, Machines. Environmental Product Declaration: AC Generator Type AMG 0900, 5152 kVA Power. (ABB, 2000).

Schneider Electric. Product Environmental Profile: Metered Rack Power Distribution (PDU) (APC, 2012).

ABB T&D S.p.A. Environmental Product Declaration: Large Distribution Transformer 16/20 MVA (ONAN/ONAF) (EPD, 2003).

Simonson, C. J. & Nyman, M. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Air-Handling Units with and without Air-to-Air Energy Exchangers (AIVC, 2004).

Schneider Electric. Product Environmental Profile: I-Line I & II Fusible Plug-in Unit (Schneider Electric, 2020).

US Energy Information Administration. Electricity Explained: Electricity in the United States (EIA, 2022).

Center for Sustainable Systems, University of Michigan. U.S. Water Supply and Distribution Factsheet (Center for Sustainable Systems, 2021).

Siddik, M. A. B., Shehabi, A. & Marston, L. The environmental footprint of data centers in the United States. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 064017 (2021).

IEA. Renewable Electricity www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2022/renewable-electricity (IEA, 2022).

Charbonnier, F., Morstyn, T. M. & McCulloch, M. D. Coordination of resources at the edge of the electricity grid: Systematic review and taxonomy. Appl. Energy 318, 119188 (2022).

Microsoft. 2021 Environmental Sustainability Report (Microsoft, 2022).

Open letter on EPD adoption. The iMasons Climate Accord (16 July 2024).

LiquidStack. Understanding different approaches to immersion cooling. LiquidStack https://liquidstack.com/blog/understanding-different-approaches-to-immersion-cooling#:~:text=The%20benefits%20of%20one-phase%20immersion%20cooling%20include%3A%20Better,About%2010X%20heat%20rejection%20capacity%20vs.%20air%20cooling (2021).

LiquidStack. White paper: Two-phase vs single phase immersion cooling fluids: deconstructing myths with science. LiquidStack https://liquidstack.com/white-papers/fluorinated-cooling-fluids-101 (2022).

Wisthoff, A., Ferrero, V., Huynh, T. & DuPont, B. Quantifying the impact of sustainable product design decisions in the early design phase through machine learning. In International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (2016).

Alissa, H., Sinistore, J. & Lio, K. (eds) Guidelines: Life Cycle Assessment, LCA Guidelines for Cloud Providers (Open Compute Project, 2022).

Judge, P. Microsoft to warm homes with waste heat from Danish data center. Data Center Dynamics (5 March 2024).

Kleyman, B. From modernization to modular: new design considerations. Data Center Frontier (19 November 2021); https://datacenterfrontier.com/modernization-demands-new-modular-datacenter-design-considerations/.

Boyd, S. B. Life-Cycle Assessment of Semiconductors (Springer, 2012).

EVAPCO. Adiabatic Cooling 101. EVAPCO. https://www.evapco.com/adiabatic-cooling-101 (2022).

Frye, D. J. & Guntner The benefits of using adiabatic cooling. Process Cooling Equipment (2021); https://www.proquest.com/docview/2766091709/1283ABB8CE674451PQ/4?sourcetype=Trade%20Journals.

Edelen, A. & Ingwersen, W. Guidance on Data Quality Assessment for Life Cycle Inventory Data (EPA, 2016).

Alissa, H., Nick, T. & Sinistore, J. Life cycle assessment (LCA) tools used for “Using life cycle assessment to drive innovation for a sustainable and cool cloud” by Alissa et al. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14268168 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank the contributions from the Microsoft and WSP teams for their work on the comparative cooling technologies LCA, on which this article is based. We are particularly grateful to N. Sundar, L. Bitar, J. Cheng, S. Danino-Beck, S. Buffaloe, J. Miller, D. Fehrer, S. Gilges, J. Delapaz, D. Millard Hastings, P. Fleming, D. Stupple, J. Halpern and A. Narasimhan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.A. conceived and designed the study. H.A., T.N. and J.S. wrote the paper. J.S., M.N., P.A., M. Frieze, L.J. and V.M. contributed expert LCA knowledge, performed detailed analyses and reviewed drafts of the paper. H.A., T.N., A.R., A.A.H., K.F., K.L., I.M., B.W., T.J.D., K.O.-S., V.O., B.R., N.G., R.B., J.K., C.B. and M. Fontoura contributed expert data centre knowledge and information and reviewed drafts of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors are/were employees of Microsoft or WSP.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Yulong Ding and Nan Li for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Process Flow Diagram and Pedigree Matrix. A diagram of the data sources, their inter-relationships, and equations used in the study.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alissa, H., Nick, T., Raniwala, A. et al. Using life cycle assessment to drive innovation for sustainable cool clouds. Nature 641, 331–338 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08832-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08832-3

This article is cited by

-

Advancing cooling limits with 3D embedded microchannels

Nature Electronics (2025)

-

Environmental impact and net-zero pathways for sustainable artificial intelligence servers in the USA

Nature Sustainability (2025)