Abstract

With the near eradication of poliovirus due to global vaccination campaigns, attention has shifted to other enteroviruses that can cause polio-like paralysis syndrome (now termed acute flaccid myelitis)1,2,3. In particular, enterovirus D68 (EV-D68) is believed to be the main driver of epidemic outbreaks of acute flaccid myelitis in recent years4, yet not much is known about EV-D68 host interactions. EV-D68 is a respiratory virus5 but, in rare cases, can spread to the central nervous system to cause severe neuropathogenesis. Here we use genome-scale CRISPR screens to identify the poorly characterized multipass membrane transporter MFSD6 as a host entry factor for EV-D68. Knockout of MFSD6 expression abrogated EV-D68 infection in cell lines and primary cells corresponding to respiratory and neural cells. MFSD6 localized to the plasma membrane and was required for viral entry into host cells. MFSD6 bound directly to EV-D68 particles through its extracellular, third loop (L3). We determined the cryo-electron microscopy structure of EV-D68 in a complex with MFSD6 L3, revealing the interaction interface. A decoy receptor, engineered by fusing MFSD6 L3 to Fc, blocked EV-D68 infection of human primary lung epithelial cells and provided near-complete protection in a lethal mouse model of EV-D68 infection. Collectively, our results reveal MFSD6 as an entry receptor for EV-D68, and support the targeting of MFSD6 as a potential mechanism to combat infections by this emerging pathogen with pandemic potential.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The FASTQ files for CRISPR screens generated in this study have been deposited at Array Express (E-MTAB-14765). The MAGeCK analysis of the CRISPR screens and datasets analysed during the current study are appended as Supplementary Data. MFSD6 expression data (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000151690-MFSD6/tissue) were retrieved from the Human Protein Atlas (v.24.0). The cryo-EM maps generated in this study have been deposited at the EMDB under accession numbers EMD-48705 and EMD-48713 for the EV-D68 apo and EV-D68 + Fc-MFSD6(L3) maps, respectively. The cryo-EM models generated in this study have been deposited at the PDB under accession numbers 9MWZ and 9MXC for the EV-D68 apo and EV-D68 + Fc-MFSD6(L3) models, respectively. Source MS data are available at the MassIVE repository under identifier MSV000096996 and the PRIDE repository via ProteomeXchange under identifier PXD060344. The default pGlyco human N-glycan database was used for proteomics data analysis53. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Morens, D. M., Folkers, G. K. & Fauci, A. S. Acute flaccid myelitis: something old and something new. mBio 10, e00521-19 (2019).

Murphy, O. C. et al. Acute flaccid myelitis: cause, diagnosis, and management. Lancet 397, 334–346 (2021).

Peters, C. E. & Carette, J. E. Return of the neurotropic enteroviruses: co-opting cellular pathways for infection. Viruses 13, 166 (2021).

Messacar, K. et al. Enterovirus D68 and acute flaccid myelitis-evaluating the evidence for causality. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, e239–e247 (2018).

Oberste, M. S. et al. Enterovirus 68 is associated with respiratory illness and shares biological features with both the enteroviruses and the rhinoviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 85, 2577–2584 (2004).

Heckenberg, E., Steppe, J. T. & Coyne, C. B. Enteroviruses: the role of receptors in viral pathogenesis. Adv. Virus Res. 113, 89–110 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Sialic acid-dependent cell entry of human enterovirus D68. Nat. Commun. 6, 8865 (2015).

Baggen, J. et al. Enterovirus D68 receptor requirements unveiled by haploid genetics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 1399–1404 (2016).

Wei, W. et al. ICAM-5/telencephalin is a functional entry receptor for enterovirus D68. Cell Host Microbe 20, 631–641 (2016).

Hixon, A. M., Clarke, P. & Tyler, K. L. Contemporary circulating enterovirus d68 strains infect and undergo retrograde axonal transport in spinal motor neurons independent of sialic acid. J. Virol. 93, e00578-19 (2019).

Sanson, K. R. et al. Optimized libraries for CRISPR-Cas9 genetic screens with multiple modalities. Nat. Commun. 9, 5416 (2018).

Li, W. et al. MAGeCK enables robust identification of essential genes from genome-scale CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screens. Genome Biol. 15, 554 (2014).

Bagchi, S. et al. Probable role for major facilitator superfamily domain containing 6 (MFSD6) in the brain during variable energy consumption. Int. J. Neurosci. 130, 476–489 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. CLN7 is an organellar chloride channel regulating lysosomal function. Sci. Adv. 7, eabj9608 (2021).

Steenhuis, P., Herder, S., Gelis, S., Braulke, T. & Storch, S. Lysosomal targeting of the CLN7 membrane glycoprotein and transport via the plasma membrane require a dileucine motif. Traffic 11, 987–1000 (2010).

Shaner, N. C. et al. A bright monomeric green fluorescent protein derived from Branchiostoma lanceolatum. Nat. Methods 10, 407–409 (2013).

Malaker, S. A. et al. Revealing the human mucinome. Nat. Commun. 13, 3542 (2022).

Termini, J. M. et al. HEK293T cell lines defective for O-linked glycosylation. PLoS ONE 12, e0179949 (2017).

Roberts, D. S. et al. Top-down proteomics. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 4, 38 (2024).

Bagdonaite, I. et al. Glycoproteomics. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2, 48 (2022).

Roberts, D. S. et al. Structural O-glycoform heterogeneity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein receptor-binding domain revealed by top-down mass spectrometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 12014–12024 (2021).

Struwe, W. B. & Robinson, C. V. Relating glycoprotein structural heterogeneity to function—insights from native mass spectrometry. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 58, 241–248 (2019).

Rossmann, M. G., He, Y. & Kuhn, R. J. Picornavirus-receptor interactions. Trends Microbiol. 10, 324–331 (2002).

Rosenfeld, A. B., Warren, A. L. & Racaniello, V. R. Neurotropism of enterovirus D68 isolates is independent of sialic acid and is not a recently acquired phenotype. mBio 10, e02370-19 (2019).

Yeh, M. T., Capponi, S., Catching, A., Bianco, S. & Andino, R. Mapping attenuation determinants in enterovirus-D68. Viruses 12, 867 (2020).

Watarastaporn, T. et al. Studies of C57BL/6J mice deficient in receptors for IFNα/β and IFNγ as a model for EV-D68 acute flaccid myelitis. Comp. Med. 74, 392–398 (2024).

McCulloch, K. A., Qi, Y. B., Takayanagi-Kiya, S., Jin, Y. & Cherra, S. J. 3rd Novel mutations in synaptic transmission genes suppress neuronal hyperexcitation in Caenorhabditis elegans. G3 7, 2055–2063 (2017).

Kim, K. W. et al. Expanded genetic screening in Caenorhabditis elegans identifies new regulators and an inhibitory role for NAD+ in axon regeneration. eLife 7, e39756 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. MFSD6 is an entry receptor for respiratory enterovirus D68. Cell Host Microbe 33, 267–278 (2025).

Dermody, T. S., Kirchner, E., Guglielmi, K. M. & Stehle, T. Immunoglobulin superfamily virus receptors and the evolution of adaptive immunity. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000481 (2009).

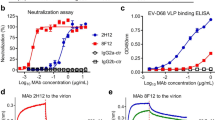

Zhang, C. et al. Functional and structural characterization of a two-MAb cocktail for delayed treatment of enterovirus D68 infections. Nat. Commun. 12, 2904 (2021).

Vogt, M. R. et al. Human antibodies neutralize enterovirus D68 and protect against infection and paralytic disease. Sci. Immunol. 5, eaba4902 (2020).

Bai, L., Sato, H., Kubo, Y., Wada, S. & Aida, Y. CAT1/SLC7A1 acts as a cellular receptor for bovine leukemia virus infection. FASEB J. 33, 14516–14527 (2019).

Ericsson, T. A. et al. Identification of receptors for pig endogenous retrovirus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 6759–6764 (2003).

Overbaugh, J., Miller, A. D. & Eiden, M. V. Receptors and entry cofactors for retroviruses include single and multiple transmembrane-spanning proteins as well as newly described glycophosphatidylinositol-anchored and secreted proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65, 371–389 (2001).

Dvorak, V. & Superti-Furga, G. Structural and functional annotation of solute carrier transporters: implication for drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 18, 1099–1115 (2023).

Ma, H. et al. LDLRAD3 is a receptor for Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. Nature 588, 308–314 (2020).

Arimori, T. et al. Engineering ACE2 decoy receptors to combat viral escapability. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 43, 838–851 (2022).

Allen, M., Bjerke, M., Edlund, H., Nelander, S. & Westermark, B. Origin of the U87MG glioma cell line: Good news and bad news. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 354re3 (2016).

Dehairs, J., Talebi, A., Cherifi, Y. & Swinnen, J. V. CRISP-ID: decoding CRISPR mediated indels by Sanger sequencing. Sci. Rep. 6, 28973 (2016).

Clement, K. et al. CRISPResso2 provides accurate and rapid genome editing sequence analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 224–226 (2019).

Sage, D. et al. DeconvolutionLab2: an open-source software for deconvolution microscopy. Methods 115, 28–41 (2017).

Campeau, E. et al. A versatile viral system for expression and depletion of proteins in mammalian cells. PLoS ONE 4, e6529 (2009).

Wessels, E., Duijsings, D., Notebaart, R. A., Melchers, W. J. G. & van Kuppeveld, F. J. M. A proline-rich region in the coxsackievirus 3A protein is required for the protein to inhibit endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi transport. J. Virol. 79, 5163–5173 (2005).

McKnight, K. L. & Lemon, S. M. Capsid coding sequence is required for efficient replication of human rhinovirus 14 RNA. J. Virol. 70, 1941–1952 (1996).

Malaker, S. A. et al. The mucin-selective protease StcE enables molecular and functional analysis of human cancer-associated mucins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 7278–7287 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Structure and inhibition of EV-D68, a virus that causes respiratory illness in children. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1261962 (2015).

Liu, Y. et al. Molecular basis for the acid-initiated uncoating of human enterovirus D68. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E12209–E12217 (2018).

de Vries, E. et al. Quantification of receptor association, dissociation, and NA-dependent motility of influenza A particles by biolayer interferometry. Methods Mol. Biol. 2556, 123–140 (2022).

Rogers, H. T. et al. Comprehensive characterization of endogenous phospholamban proteoforms enabled by photocleavable surfactant and top-down proteomics. Anal. Chem. 95, 13091–13100 (2023).

Larson, E. J. et al. MASH Native: a unified solution for native top-down proteomics data processing. Bioinformatics 39, btad359 (2023).

Marty, M. T. et al. Bayesian deconvolution of mass and ion mobility spectra: from binary interactions to polydisperse ensembles. Anal. Chem. 87, 4370–4376 (2015).

Zeng, W.-F., Cao, W.-Q., Liu, M.-Q., He, S.-M. & Yang, P.-Y. Precise, fast and comprehensive analysis of intact glycopeptides and modified glycans with pGlyco3. Nat. Methods 18, 1515–1523 (2021).

Adams, T. M., Zhao, P., Kong, R. & Wells, L. ppmFixer: a mass error adjustment for pGlyco3.0 to correct near-isobaric mismatches. Glycobiology 34, cwae006 (2024).

Kong, A. T., Leprevost, F. V., Avtonomov, D. M., Mellacheruvu, D. & Nesvizhskii, A. I. MSFragger: ultrafast and comprehensive peptide identification in mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nat. Methods 14, 513–520 (2017).

Polasky, D. A., Yu, F., Teo, G. C. & Nesvizhskii, A. I. Fast and comprehensive N- and O-glycoproteomics analysis with MSFragger-Glyco. Nat. Methods 17, 1125–1132 (2020).

Scheres, S. H. W. RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J. Struct. Biol. 180, 519–530 (2012).

Zheng, S. Q. et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017).

Rohou, A. & Grigorieff, N. CTFFIND4: fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J. Struct. Biol. 192, 216–221 (2015).

Wagner, T. et al. SPHIRE-crYOLO is a fast and accurate fully automated particle picker for cryo-EM. Commun. Biol. 2, 218 (2019).

Punjani, A., Rubinstein, J. L., Fleet, D. J. & Brubaker, M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017).

Liebschner, D. et al. Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in Phenix. Acta Crystallogr. D 75, 861–877 (2019).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF ChimeraX: structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 30, 70–82 (2021).

Croll, T. I. ISOLDE: a physically realistic environment for model building into low-resolution electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr. D 74, 519–530 (2018).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D 60, 2126–2132 (2004).

Pintilie, G. et al. Measurement of atom resolvability in cryo-EM maps with Q-scores. Nat. Methods 17, 328–334 (2020).

Zhang, K., Pintilie, G. D., Li, S., Schmid, M. F. & Chiu, W. Resolving individual atoms of protein complex by cryo-electron microscopy. Cell Res. 30, 1136–1139 (2020).

Kretsch, R. C. et al. Complex water networks visualized by cryogenic electron microscopy of RNA. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08855-w (2025).

Chen, V. B. et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 12–21 (2010).

Krissinel, E. & Henrick, K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797 (2007).

Krissinel, E. Stock-based detection of protein oligomeric states in jsPISA. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W314–W319 (2015).

Xiao, C. & Rossmann, M. G. Interpretation of electron density with stereographic roadmap projections. J. Struct. Biol. 158, 182–187 (2007).

Zheng, Q. et al. Atomic structures of enterovirus D68 in complex with two monoclonal antibodies define distinct mechanisms of viral neutralization. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 124–133 (2019).

Hrebík, D. et al. ICAM-1 induced rearrangements of capsid and genome prime rhinovirus 14 for activation and uncoating. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2024251118 (2021).

National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals 8th edn (National Academies Press, 2010).

Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (US Department of Health and Human Services, NIH Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare, 2015).

Mao, Q. et al. A neonatal mouse model of coxsackievirus A16 for vaccine evaluation. J. Virol. 86, 11967–11976 (2012).

Karlsson, M. et al. A single-cell type transcriptomics map of human tissues. Sci. Adv. 7, eabh2169 (2021).

Uhlén, M. et al. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 347, 1260419 (2015).

Hadfield, J. et al. Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics 34, 4121–4123 (2018).

Sagulenko, P., Puller, V. & Neher, R. A. TreeTime: maximum-likelihood phylodynamic analysis. Virus Evol. 4, vex042 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of J.E.C.’s laboratory and the members of W.C.’s laboratory, especially A. Dupzyk, B. Waldman and F. Cooper, for their feedback and insights; I. L. Weissman, G. Tender and C. Xiao for their advice and feedback; M. Amieva and D. Monack for the use of their confocal microscope; D. Monack for the use of her tissue homogenizer; the members of the ISCRBM FACS Core for the use of their Sony MA900 system. Schematics in Figs. 1a and 2f,g were created using BioRender. This work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) T32G Stanford Cellular and Molecular Biology Training Program M007276 (to L.V.); NIH T32 AI00732 (to C.E.P.); NIH R01 CA200423 (to C.R.B.); NIH R01 AI169467 (to J.E.C.); NIH R01 AI153169 (to J.E.C.); NIH R01 AI140186 (to J.E.C.); National Science Foundation (NSF) GRFP DGE-1656518 (to L.X.), NSF DGE-1656518 (to C.E.P.) and NSF DGE-2146755 (to S.R.); Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation DRG-2526-24 (to D.S.R.); Burroughs Wellcome Fund Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease (to J.E.C.); Stanford Maternal & Child Health Research Institute (to W.Q.); European Union’s Horizon Research and Innovation program PANVIPREP (grant number 101003627) (to F.J.M.v.K.); and EU Horizon ERC Advanced Grant program VIRLUMINOUS (grant number 01053576) (to F.J.M.v.K). Cell sorting was done through the Stanford Shared FACS Facility (RRID: SCR_017788) using either the BD FACSAria II (funded by NIH S10RR025518-01) or BD FACSFusion (purchased by the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunology) sorter. Cryo-EM data were collected at the Stanford-SLAC CryoEM Center (supported by the NIH Common Fund Transformative High-Resolution Cryo-Electron Microscopy program U24GM129541 to W.C.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.E.P., Y.S.O. and J.D. contributed to project conception. L.V., L.X. and J.E.C. contributed to experimental design. C.E.P., Y.S.O., J.D., W.Q. and C.M.R. contributed to CRISPR library construction. L.V. and C.E.P. performed CRISPR–Cas9 knockout screens and L.V. and W.Q. performed data analysis. L.V. engineered cell lines, propagated viruses, generated the replicon and cloned Fc constructs. L.V. conducted the replicon assay, IP assay, cell inhibition assay, RT–qPCR and western blots. L.V. and L.X. generated knockout cells and performed PFU production assays. L.X. purified virus and Fc constructs, conducted cell surface biotinylation, and viral binding and internalization assays. S.R., L.X. and L.V. engineered iPS cells and differentiated iPS cells. L.V., L.X., C.E.P., S.R. and J.C. performed immunofluorescence imaging and L.X., C.E.P. and S.J. performed confocal data analysis. L.X. conducted cryo-EM imaging and data processing. G.P. conducted modelling and generated the interaction video. W.C. provided structural insights. L.V., L.X. and C.M.N. performed in vivo mouse experiments. D.S.R. conducted MS and analysis. C.R.B. provided insights on glycobiology. M.L., E.d.V. and F.J.M.v.K. conducted BLI and analysis. L.V., L.X. and J.E.C. interpreted the experimental data and wrote the manuscript. L.V., L.X. and G.P. generated figures. W.C. and J.E.C. supervised the research. All of the authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript before submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.E.C. consulted for Janssen BioPharma on topics unrelated to this study. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Ming Luo, Kenneth Tyler and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Expression of MFSD6 and characterization of ΔMFSD6 cells.

(a) RNA expression of MFSD6 from Human Protein Atlas80,81 using the GTEx dataset. nTPM is the normalized protein-coding transcripts per million. (b) Percentage of edited DNA harvested from pooled knockouts (KOs). Analysis was done with CRISPResso2. (c) Detection of MFSD6 by western blot in A549 cells (top) and U87-MG cells (bottom) using an endogenous MFSD6 antibody. The black triangle points to MFSD6. (d) Representative immunofluorescence images, zoomed in, from two independent experiments for A549 wild-type (left), A549 ΔMFSD6 cells (middle left), U87-MG wild-type (middle right), and U87-MG ΔMFSD6 cells (right) infected with EV-D68 (MOI = 5) for 24 h and stained for EV-D68 VP1 (green). Nuclei are labelled with Hoechst (blue). Percentages indicate the mean with s.e.m. (n = 5 images). Over 500 cells were imaged for each condition. Scale bar, 25 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Characterization of MFSD6 clonal knockouts made in iPSC-derived neurons.

(a) Sanger sequencing of wild-type cells and MFSD6 knockout clones in iPSC-derived neurons. Two ΔMFSD6 clones were generated. ΔMFSD6 1 has mixed sequencing and ΔMFSD6 2 has a 99 bp deletion. The black underline refers to the guide sequence, the red underline is the PAM site, and the black dash is the cleavage site. Sequences were analysed using CRISP-ID and Synthego Performance Analysis, ICE Analysis. (b) Representative immunofluorescence images, zoomed in, from two independent experiments for non-target cells and ΔMFSD6 cells. Cells are co-stained with the neuronal marker TUJ1 (green) and DAPI (blue). A full 96-well scan of images containing over 500 cells was taken for each condition. Scale bars, 5 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Characterization of MFSD6 and SLC35A1 clonal knockout cell lines.

(a) Sanger sequencing of wild-type cells and MFSD6 knockout clones in A549 and U87-MG cells. The A549 clone has a one base pair insertion. The U87-MG clone has a one base pair and two base pair insertion. The black underline refers to the guide sequence, the red underline is the PAM site, and the black dash is the cleavage site. Sequences were analysed using CRISP-ID and Synthego Performance Analysis, ICE Analysis. (b) Sanger sequencing of wild-type cells and SLC35A1 knockout clones in A549 and U87-MG cells. The A549 clone has a two base pair deletion. The U87-MG clone has a two base pair insertion and other mixed sequencing. The black underline refers to the guide sequence, the red underline is the PAM site, and the black dash is the cleavage site. Sequences were analysed using CRISP-ID and Synthego Performance Analysis, ICE Analysis. (c) Representative immunofluorescence images, zoomed in, from two independent experiments for WT, MFSD6 knockout (KO), MFSD6 add back (AB) , and SLC35A1 knockout cells in A549 and U87-MG cell lines (n = 5 images for each cell line). Cells are co-stained with SNA-FITC (green) and nuclei are stained with Hoechst (blue). Over 50 cells were imaged for each condition. Scale bar for A549 cells, 10 μm. Scale bar for U87-MG cells, 20 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Characterization of other enteroviruses and other EV-D68 strains in ΔMFSD6 cells.

(a) Dendrogram of different strains of EV-D68 used for infection. Dendrogram was based on Nextstrain82,83. (b-c) Wild-type, ΔMFSD6, and ΔMFSD6 + A549 cells were infected (MOI = 1), and harvested for PFU production after 24 h (n = 3, biological replicates) (b) or stained for crystal violet after 5 days (c). (d) RT–qPCR analysis of various enteroviruses in U87-MG cells. Cells were infected (MOI = 5), and harvested 24 h post-infection. Samples were normalized to WT as 100% infection (n = 3, biological replicates). (e) Crystal violet stains of wild-type, ΔMFSD6, ΔMFSD6 + , and ΔMFSD6 + MFSD6-mNeon A549 cells infected with EV-D68 (MOI = 1) and fixed after 5 days. (f) Schematic of EV-D68 replicon. Renilla luciferase replaces VP4, VP2, and part of VP3. Datasets show mean and error bars show s.e.m. All P values are indicated and were determined by one-way ANOVA (Holm–Sidak corrected) on log-transformed data.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Characterization and validation of A549 ΔMFSD6+ overexpression constructs, Fc constructs, and purified EV-D68.

(a) Western blot for MFSD6 and MFSD8 in A549 wild-type, ΔMFSD6, ΔMFSD6+ , ΔMFSD6 + MFSD6ΔL3, MFSD6 + MFSD8, ΔMFSD6 + MFSD8(LS), and ΔMFSD6 + MFSD6-mNeon cells. The black triangle indicates MFSD6 or MFSD8. (b) Coomassie stain of purified Fc constructs (left) and purified EV-D68 (right). (c) Western blot of immunoprecipitation (IP) of Fc-MFSD6(L3) and Fc-MFSD8(L9) with EV-D68 or EV-A71. (d) Biolayer interferometry (BLI) assay. The biosensor was coupled with Fc-MFSD6(L3) (green), Fc-MFSD8(L9) (grey), or PBS (blue) and binding with 2 * 109 PFU ml−1 CVB3 was determined. Fc constructs were loaded at 0.2 μg μl−1 and reached saturation. (e) Gradient banding pattern from 10–50% (w/v) iodixanol gradient and corresponding fractions taken for (f) western blotting against EV-D68 viral capsid proteins and plaque assay (g). Fractions I and J contained bands corresponding to the mature virus, which were combined and used for cryo-EM, with representative micrographs shown for (h) apo EV-D68 (from 10,400 micrographs) and (i) EV-D68 bound to Fc-MFSD6(L3) (from 11,869 micrographs). Scale bars, 20 nm.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Top-down and bottom-up glycoproteomics characterizing Fc-MFSD6(L3) glycoforms.

(a) Protein sequence table showing all identified N- and O-glycosites found for the Fc-MFSD6(L3) construct. (b) Top-down MS analysis of Fc-MFSD6(L3) construct expressed from wild-type cells (HEK293FT) (bottom) and cells deficient in O-linked glycosylation machinery (HEK293T ΔGALE/ΔGALK2 knockout) (top). Heterogeneity, imparted by the various O-glycosylation sites and structures, is observed in the wild-type Fc-MFSD6(L3). These O-glycan modifications are ablated in the Fc-MFSD6(L3) produced in ΔGALE/ΔGALK2 cells, resulting in a substantial mass loss and simplification of the intact protein mass spectra, due to reduction of multiple overlapping ion signals from the various glycoforms. (c) Western blot of Fc-MFSD6(L3) produced in wild-type and O-linked glycosylation deficient cells. The proteins were incubated with StcE, a protease that specifically cleaves mucin-domain glycoproteins. (d) Tandem MS analysis by HCD confirming the presence of core fucosylated N-glycan structure (Man3GlcNAc2Fuc1) located on N207 (representative glycopeptide LnVSDTVTLPTAPNMNSEPTLQPQTGEITNR) and resolved by the cryo-EM map shown in Fig. 4b. All b and y fragment ions are represented by the cyan and pink fragment labels, respectively. (e) Representative tandem MS spectra showing the diversity of the various N-glycan structures (Man3GlcNAc5Fuc1, Man3GlcNAc6Fuc1, and Man3GlcNAc4Gal1NeuAc1Fuc1) characterized by HCD at N207 and represented in Fig. 4c. All b and y fragment ions are represented by the cyan and pink fragment labels, respectively. All spectral assignments are within 2 ppm of total mass error.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Cryo-EM data processing workflow.

Workflow for cryo-EM data processing for (a) EV-D68 apo and (b) EV-D68 + Fc-MFSD6(L3). Data was processed in Relion until 3D classification, after which particle stacks were imported into cryoSPARC. Icosahedral symmetry was applied only in cryoSPARC during Ab Initio and Homogeneous Refinement. Following refinement in cryoSPARC, the unsharpened maps were input into Phenix for auto-sharpening.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Q-score model validation for cryo-EM models.

Representative images of proteins, waters, ions, or glycans and corresponding Q-score plots for the EV-D68 apo map and model, depicting (a) VP1 (chain A, blue), (b) VP2 (chain B, green), (c) VP3 (chain C, red), (d) VP4 (chain D, brown), and (e) waters (each dot denotes a single water); and for the EV-D68 + Fc-MFSD6(L3) map and model, depicting (f) VP1 (chain A), (g) VP2 (chain B), (h) VP3 (chain C), (i), VP4 (chain D), (j) waters and ions (each dot denotes a single water or ion), and (k) Fc-MFSD6(L3) (chains E-F), with separate plots for the protein backbone (chain E) and glycan chain (chain F). Maps are shown in grey with transparency. Models are coloured by chain or by atomic colouring. For Fc-MFSD6(L3), protein Q-scores are plotted in black, and glycan Q-scores are plotted with colours matching the monosaccharide identity (GlcNAc, denoted NAG in blue, mannose, denoted BMA or MAN, in green, and fucose, denoted FUC, in red). Q-scores for protein residues, water, and glycans are plotted with filled circles. Q-scores for ions (3 points in (j)) are plotted with open circles. Dashed lines indicate the most commonly observed Q-score (black, Q_Peak) for maps in the EMDB at similar resolutions in addition to upper bounds (blue, Q_High 95%) and lower bounds (red, Q_Low 95%) that enclose 95% of observed maps for that resolution.

Extended Data Fig. 9 EV-D68 residues interacting with Fc-MFSD6(L3).

(a) Interactions within 4 Å distance from the Fc-MFSD6(L3) (chain E). The model for EV-D68 in complex with Fc-MFSD6(L3) is coloured, with VP1 (purple) and VP3 (red). The model for apo EV-D68 is grey. Residues between L1208 and T1216 are part of the VP1 GH loop. Fc-MFSD6(L3) is yellow, with start and end residues labelled. (b) Hydrogen bonding and salt bridge interactions and distances from PISA. *Indicates interaction not found by PISA but measured in Chimera. The atom ID starts with the atom (H (hydrogen), O (oxygen), N (nitrogen)). Protein atom IDs with one letter belong to the main chain; others belong to the side chain. Glycan atom IDs are relative to carbon numbering. NAG represents GlcNAc. (c-d) Selected interactions (also shown in Supplementary Video 1) show residues interacting with (c) R205 with H-bonds and (d) two GlcNAcs with H-bonds. The model is in atomic colouring (carbon (grey), hydrogen (white), oxygen (red), nitrogen (blue)). The map is transparent grey. Hydrogen bonds are shown with dashed lines. (e) EV-D68 RIVEM roadmap plot showing interacting residues. The large triangle marks the boundary of the projected asymmetric unit. The icosahedral symmetry axes are indicated by an oval, triangle, and pentagon. Residues interacting with Fc-MFSD6(L3) (chains E-F) within 4 Å distance are coloured by capsid protein with VP1 (purple), VP2 (green), and VP3 (red). A bright red outline marks capsid residues with H-bonds or a salt bridge with Fc-MFSD6(L3) (also in (b)). (f) EV-D68 RIVEM roadmap coloured by radial distance from 135 Å (blue) to 160 Å (red). A bright yellow outline marks capsid residues interacting with Fc-MFSD6(L3) within 4 Å distance and encloses part of the canyon, a depressed region (blue).

Extended Data Fig. 10 Comparison of EV-D68 receptor binding with other enterovirus ligands.

Asymmetric units of ligand-bound enteroviruses for structural comparison. A legend shows colourings for enterovirus capsid proteins, with VP1 in light purple, VP2 in light green, and VP3 in light red. Residues within a 4 Å interaction radius are shown in bright purple, green, and red surfaces, respectively. VP4 (behind) is not visible in this view. Ligand-bound enteroviruses include (a) RV-B14 and ICAM-1 (PDB ID: 7BG7); (b) EV-D68 and Fc-MFSD6(L3), in which the interaction involves Fc-MFSD6(L3) chains E-F but chain F is removed for clarity; (c) EV-D68 and sialic acid (PDB ID: 5BNO); (d) EV-D68 and 8F12 Fab (PDB ID: 7EC5); (e) EV-D68 and 2H12 Fab (state S1) (PDB ID: 7EBZ); and (f) EV-D68 and EV68-228 Fab (PDB ID: 6WDT). Ligands are shown in yellow (b-c) or transparent orange (a, d-f).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table 1

Dataset of A549 EV-D68 CRISPR screens. Genome-scale CRISPR screen datasets were analysed using the MAGeCK algorithm. P values are calculated using MAGeCK. P values are one-sided. FDR-adjusted P values were multiple-hypothesis corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure

Supplementary Table 2

Dataset of U87-MG EV-D68 CRISPR screens. Genome-scale CRISPR screen datasets were analysed using the MAGeCK algorithm. P values are calculated using MAGeCK. P values are one-sided. FDR-adjusted P values were multiple-hypothesis corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure.

Supplementary Video 1

Video of interactions between EV-D68 and Fc–MFSD6(L3) resolved by cryo-EM. Video showing the cryo-EM structure of EV-D68 in complex with Fc–MFSD6(L3) and visualizing the interaction interface

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Varanese, L., Xu, L., Peters, C.E. et al. MFSD6 is an entry receptor for enterovirus D68. Nature 641, 1268–1275 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08908-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08908-0

This article is cited by

-

Neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies to poliovirus map to the receptor binding site

Nature Communications (2026)

-

Virion motility of sialoglycan-cleaving respiratory viruses

npj Viruses (2025)

-

Structural insights from vaccine candidates for EV-D68

Communications Biology (2025)

-

Structural insights into cationic amino acid transport and viral receptor engagement by CAT1

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Structure and mechanism of the mitochondrial calcium transporter NCLX

Nature (2025)