Abstract

Vision enables many animals to perform spatial reasoning from remote locations1. By viewing distant landmarks, animals recall spatial memories and plan future trajectories. Although these spatial functions depend on hippocampal place cells2,3, the relationship between place cells and active visual behaviour is unknown. Here we studied a highly visual animal, the chickadee, in a behaviour that required alternating between remote visual search and spatial navigation. We leveraged the head-directed nature of avian vision to track gaze in freely moving animals. We discovered a profound link between place coding and gaze. Place cells activated not only when the chickadee was in a specific location, but also when it simply gazed at that location from a distance. Gaze coding was precisely timed by fast ballistic head movements called ‘head saccades’4,5. On each saccadic cycle, the hippocampus switched between encoding a prediction of what the bird was about to see and a reaction to what it actually saw. The temporal structure of these responses was coordinated by subclasses of interneurons that fired at different phases of the saccade. We suggest that place and gaze coding are components of a unified process by which the hippocampus represents the location that is relevant to the animal in each moment. This process allows the hippocampus to implement both local and remote spatial functions.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data are available at https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.tqjq2bw9n.

Code availability

Example code is available at https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.tqjq2bw9n.

References

Meister, M. L. R. & Buffalo, E. A. Getting directions from the hippocampus: the neural connection between looking and memory. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 134, 135–144 (2016).

O’Keefe, J. & Dostrovsky, J. The hippocampus as a spatial map. Preliminary evidence from unit activity in the freely-moving rat. Brain Res. 34, 171–175 (1971).

Colgin, L. L., Moser, E. I. & Moser, M.-B. Understanding memory through hippocampal remapping. Trends Neurosci. 31, 469–477 (2008).

Land, M. F. Eye movements of vertebrates and their relation to eye form and function. J. Comp. Physiol. A 201, 195–214 (2015).

Kane, S. A. & Zamani, M. Falcons pursue prey using visual motion cues: new perspectives from animal-borne cameras. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 225–234 (2014).

Wallace, D. J. et al. Rats maintain an overhead binocular field at the expense of constant fusion. Nature 498, 65–69 (2013).

Payne, H. L. & Raymond, J. L. Magnetic eye tracking in mice. eLife 6, e29222 (2017).

Meyer, A. F., O’Keefe, J. & Poort, J. Two distinct types of eye-head coupling in freely moving mice. Curr. Biol. 30, 2116–2130.e6 (2020).

Michaiel, A. M., Abe, E. T. & Niell, C. M. Dynamics of gaze control during prey capture in freely moving mice. eLife 9, e57458 (2020).

Rolls, E. T., Robertson, R. G. & Georges‐François, P. Spatial view cells in the primate hippocampus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 9, 1789–1794 (1997).

Killian, N. J., Jutras, M. J. & Buffalo, E. A. A map of visual space in the primate entorhinal cortex. Nature 491, 761–764 (2012).

Wirth, S., Baraduc, P., Planté, A., Pinède, S. & Duhamel, J.-R. Gaze-informed, task-situated representation of space in primate hippocampus during virtual navigation. PLoS Biol. 15, e2001045 (2017).

Mao, D. et al. Spatial modulation of hippocampal activity in freely moving macaques. Neuron 109, 3521–3534.e6 (2021).

Corrigan, B. W. et al. View cells in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex of macaques during virtual navigation. Hippocampus 33, 573–585 (2023).

Piza, D. B. et al. Primacy of vision shapes behavioral strategies and neural substrates of spatial navigation in marmoset hippocampus. Nat. Commun. 15, 4053 (2024).

Fried, I., MacDonald, K. A. & Wilson, C. L. Single neuron activity in human hippocampus and amygdala during recognition of faces and objects. Neuron 18, 753–765 (1997).

Jutras, M. J., Fries, P. & Buffalo, E. A. Oscillatory activity in the monkey hippocampus during visual exploration and memory formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13144–13149 (2013).

Gulli, R. A. et al. Context-dependent representations of objects and space in the primate hippocampus during virtual navigation. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 103–112 (2020).

Moore, B. A., Doppler, M., Young, J. E. & Fernández-Juricic, E. Interspecific differences in the visual system and scanning behavior of three forest passerines that form heterospecific flocks. J. Comp. Physiol. A 199, 263–277 (2013).

Payne, H. L., Lynch, G. F. & Aronov, D. Neural representations of space in the hippocampus of a food-caching bird. Science 373, 343–348 (2021).

Chettih, S. N., Mackevicius, E. L., Hale, S. & Aronov, D. Barcoding of episodic memories in the hippocampus of a food-caching bird. Cell 187, 1922–1935.e20 (2024).

Martin, G. R., White, C. R. & Butler, P. J. Vision and the foraging technique of Great Cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo: pursuit or close-quarter foraging? IBIS 150, 485–494 (2008).

Theunissen, L. M. & Troje, N. F. Head stabilization in the pigeon: role of vision to correct for translational and rotational disturbances. Front. Neurosci. 11, 551 (2017).

Bischof, H.-J. The visual field and visually guided behavior in the zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata). J. Comp. Physiol. A 163, 329–337 (1988).

Maldonado, P. E., Maturana, H. & Varela, F. J. Frontal and lateral visual system in birds: frontal and lateral gaze. Brain Behav. Evol. 32, 57–62 (2008).

Itahara, A. & Kano, F. Gaze tracking of large-billed crows (Corvus macrorhynchos) in a motion capture system. J. Exp. Biol. 227, jeb246514 (2024).

Wilson, M. A. & McNaughton, B. L. Dynamics of the hippocampal ensemble code for space. Science 261, 1055–1058 (1993).

Anderson, M. I. & Jeffery, K. J. Heterogeneous modulation of place cell firing by changes in context. J. Neurosci. 23, 8827–8835 (2003).

Aronov, D., Nevers, R. & Tank, D. W. Mapping of a non-spatial dimension by the hippocampal–entorhinal circuit. Nature 543, 719–722 (2017).

Pfeiffer, B. E. & Foster, D. J. Hippocampal place-cell sequences depict future paths to remembered goals. Nature 497, 74–79 (2013).

Kay, K. et al. Constant sub-second cycling between representations of possible futures in the hippocampus. Cell 180, 552–567.e25 (2020).

Felleman, D. J. & Van Essen, D. C. Distributed hierarchical processing in the primate cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex 1, 1–47 (1991).

Atoji, Y. & Wild, J. M. Projections of the densocellular part of the hyperpallium in the rostral Wulst of pigeons (Columba livia). Brain Res. 1711, 130–139 (2019).

Applegate, M. C., Gutnichenko, K. S. & Aronov, D. Topography of inputs into the hippocampal formation of a food-caching bird. J. Comp. Neurol. 531, 1669–1688 (2023).

Zeigler, H. P. & Bischof, H.-J. Vision, Brain, and Behavior in Birds (MIT Press, 1993).

Sherry, D. F., Krebs, J. R. & Cowie, R. J. Memory for the location of stored food in marsh tits. Anim. Behav. 29, 1260–1266 (1981).

Graves, J. A. & Goodale, M. A. Failure of interocular transfer in the pigeon (Columba livia). Physiol. Behav. 19, 425–428 (1977).

Gusel’nikov, V. I., Morenkov, E. D. & Hunh, D. C. Responses and properties of receptive fields of neurons in the visual projection zone of the pigeon hyperstriatum. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 8, 210–215 (1977).

Klausberger, T. et al. Brain-state- and cell-type-specific firing of hippocampal interneurons in vivo. Nature 421, 844–848 (2003).

Mehta, M. R., Lee, A. K. & Wilson, M. A. Role of experience and oscillations in transforming a rate code into a temporal code. Nature 417, 741–746 (2002).

Mizuseki, K., Sirota, A., Pastalkova, E. & Buzsáki, G. Theta oscillations provide temporal windows for local circuit computation in the entorhinal–hippocampal loop. Neuron 64, 267–280 (2009).

Agarwal, A., Sarel, A., Derdikman, D., Ulanovsky, N. & Gutfreund, Y. Spatial coding in the hippocampus and hyperpallium of flying owls. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2212418120 (2023).

Saleem, A. B., Diamanti, E. M., Fournier, J., Harris, K. D. & Carandini, M. Coherent encoding of subjective spatial position in visual cortex and hippocampus. Nature 562, 124–127 (2018).

Wilson, M. A. & McNaughton, B. L. Reactivation of hippocampal ensemble memories during sleep. Science 265, 676–679 (1994).

Johnson, A. & Redish, A. D. Neural ensembles in CA3 transiently encode paths forward of the animal at a decision point. J. Neurosci. 27, 12176–12189 (2007).

Ormond, J. & O’Keefe, J. Hippocampal place cells have goal-oriented vector fields during navigation. Nature 607, 741–746 (2022).

Mallory, C. S. et al. Mouse entorhinal cortex encodes a diverse repertoire of self-motion signals. Nat. Commun. 12, 671 (2021).

Hasselmo, M. E., Bodelón, C. & Wyble, B. P. A proposed function for hippocampal theta rhythm: separate phases of encoding and retrieval enhance reversal of prior learning. Neural Comput. 14, 793–817 (2002).

Yartsev, M. M., Witter, M. P. & Ulanovsky, N. Grid cells without theta oscillations in the entorhinal cortex of bats. Nature 479, 103–107 (2011).

Macrides, F., Eichenbaum, H. B. & Forbes, W. B. Temporal relationship between sniffing and the limbic theta rhythm during odor discrimination reversal learning. J. Neurosci. 2, 1705–1717 (1982).

Grion, N., Akrami, A., Zuo, Y., Stella, F. & Diamond, M. E. Coherence between rat sensorimotor system and hippocampus is enhanced during tactile discrimination. PLoS Biol. 14, e1002384 (2016).

Joshi, A. et al. Dynamic synchronization between hippocampal representations and stepping. Nature 617, 125–131 (2023).

Eliav, T. et al. Nonoscillatory phase coding and synchronization in the bat hippocampal formation. Cell 175, 1119–1130.e15 (2018).

Hoffman, K. et al. Saccades during visual exploration align hippocampal 3–8 Hz rhythms in human and non-human primates. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 7, 43 (2013).

Andrillon, T., Nir, Y., Cirelli, C., Tononi, G. & Fried, I. Single-neuron activity and eye movements during human REM sleep and awake vision. Nat. Commun. 6, 7884 (2015).

Shih, S.-W., Wu, Y.-T. & Liu, J. A calibration-free gaze tracking technique. In Proc. 15th International Conference on Pattern Recognition 201–204 (IEEE, 2000).

Stahl, J. S., van Alphen, A. M. & De Zeeuw, C. I. A comparison of video and magnetic search coil recordings of mouse eye movements. J. Neurosci. Methods 99, 101–110 (2000).

Li, D., Winfield, D. & Parkhurst, D. J. Starburst: a hybrid algorithm for video-based eye tracking combining feature-based and model-based approaches. In Proc. 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05) Workshops 79 (IEEE, 2005).

Pachitariu, M., Steinmetz, N. A., Kadir, S. N., Carandini, M. & Harris, K. D. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 29 (Curran Associates, 2016).

Denovellis, E. L. et al. Hippocampal replay of experience at real-world speeds. eLife 10, e64505 (2021).

Skaggs, W. E., McNaughton, B. L., Gothard, K. M. & Markus, E. J. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Vol. 5 (eds Hanson, S. J. et al.) 1030–1037 (Morgan Kaufmann, 1993)

Bahill, A. T., Clark, M. R. & Stark, L. The main sequence, a tool for studying human eye movements. Math. Biosci. 24, 191–204 (1975).

Applegate, M. C., Gutnichenko, K. S., Mackevicius, E. L. & Aronov, D. An entorhinal-like region in food-caching birds. Curr. Biol. 33, 2465–2477.e7 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Hale for technical assistance, Aronov laboratory members for helpful discussion, the Black Rock Forest Consortium, J. Scribner and Hickory Hill Farm, T. Green for fieldwork support, and J. Kuhl for the chickadee illustration in Fig. 1a. Funding was provided by the NIH BRAIN Initiative Advanced Postdoctoral Career Transition Award (K99 EY034700; H.L.P.), New York Stem Cell Foundation Robertson Neuroscience Investigator Award (D.A.), Beckman Young Investigator Award (D.A.), NIH New Innovator Award (DP2 AG071918; D.A.) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (D.A.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L.P. and D.A. designed the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the paper. H.L.P. performed the experiments.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Uwe Mayer, Jonathan Whitlock and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Properties of head movements in chickadees.

(a) Head saccade durations for an example session. (b) Relationship between angular distance travelled by the head and the peak angular speed during head saccades for the same session. (c) Relationship between distance travelled and saccade duration. Both (b) and (c) show strong correlations, illustrating similarities to the eye saccade main sequence in primates62. (d) Time courses of the two gaze strategies (orange: lateral; black: frontal). Each line represents one bird. Data are shown as in Fig. 1g, but for all 7 birds recorded in the X-shaped arena, averaged across sessions. (e) Distribution of saccade angular distances for saccades that successfully land on an unrewarded target site, as well as for the preceding and following saccades. Gazes that land on the target are produced by smaller saccades (median saccade distance 38.7° for the saccade to the target, 47.8° preceding saccade, 46.0° next saccade; saccade to target vs. previous and next, p = 0.0004 and 0.0009, two sided t-tests conducted on the median distances for each bird, n = 7 birds recorded in the X-shaped arena). This implies that gaze locations that precede successful target hits are, on average, slightly closer to the target than other gaze locations. (f) Number of saccades required by birds in the Blocked trial task to find the correct target. Each line represents one bird, error bars indicate mean ± S.E.M. across the medians for each session (n = 8, 13, 6 sessions for the three birds from top to bottom). Chickadees take longer to find the target on the first trial (when they have no information about which target is rewarded) than on subsequent trials (p = 0.007, 0.006, 4 × 10-8, two-sided t-test conducted separately for each bird). Note that when shifting gaze from one target to another, birds often make several intermediate saccades at other points in the environment.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Eye tracking method and properties of eye movements in chickadees.

(a) Video-oculography using two infrared light sources. The chickadee is perched close to two cameras, which acquire video frames from slightly different angles (top). The pupil (yellow) and the corneal reflections of the two light sources (red) are detected in the videos. Head tracking is conducted simultaneously using an array of infrared reflective markers attached to the bird’s implant (not shown). (b) Accuracy of head tracking: 0.046° root-mean-squared error (RMSE). Red dots: measurement; Black line: unity line. (c) Accuracy of eye tracking: 1.78° RMSE measured across fixations, 1.79° measured across individual frames. Dots: individual fixations. (d) Position of the eye (dots) and the orientation of the optical axis (lines) relative to the head. Projections onto the horizontal axis are shown. Gray: individual video frames for a single calibration experiment. Blue: average across frames. (e) Orientation of the optical axis across all birds (black symbols) and the average across birds (red symbols). (f) Angular displacement of the head and the eye during head saccades. Symbols indicate medians for each bird; lines indicate 25th and 75th percentiles (n = 4341 – 144521 head saccades per bird, n = 8 – 55 eye saccades per bird).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Histological analysis of recording locations.

(a) Coronal section of a typical recording location in the hippocampus, showing the track of the recording probe. The section is labeled with DAPI, which clearly delineates the lower-density hippocampus from the higher-density dorsolateral region (DL) that is directly lateral to the hippocampus. (b-d) Locations of all recorded cells registered to a 3D model of the chickadee brain constructed using data from63. Colored symbols: cells included in the paper, black lines: electrode tracks. Track locations were confirmed histologically for 8/14 probe tracks, yielding 2504/2658 cells in the X-shaped tasks and 351/361 cells in the all-to-all task (note that 5/9 birds were implanted with two-shank silicon probes). The locations of the remaining cells were estimated from stereotaxic coordinates. Lambda is located at 0 mm in the displayed coordinate axes.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Comparison of place and gaze coding across tasks.

(a-b) Place and gaze coding, shown as in Fig. 2e,f, but only for cells recorded in the Random task, where the location of the rewarded target was chosen randomly on each trial. Each row is separately normalized from 0 (blue) to the maximum (yellow). (c-d) Same, but only for cells recorded in the Blocked-trial task, where the same rewarded target was repeated for six trials in a row.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Place coding is not explained by simple visual responses.

(a-b) Saccade-aligned firing rates averaged across cells, when the bird is located at one of the corner target sites, but gazing elsewhere in the environment. Included are cells with place and gaze selectivity (>0.5) for one of the sites. For each cell, firing rates are plotted for trials when the bird is at that cell’s preferred site and when the bird is at the opposite site. Saccades are grouped according to the azimuthal direction the bird is facing. To eliminate saccades in which the bird is gazing down at the feeder, saccades are only included if the elevation of gaze is within ±30° elevation from the average vector of gaze at targets within each session (average elevation –9° across sessions). The direction of gaze is given by the contralateral eye. In all cases, cells remain selective for the bird’s location at their preferred site. Error bars indicate mean ± S.E.M. across cells. (c-d) Same as (a-b), but saccades are grouped according to whether the indicator light is on or already turned off. Although cells respond more strongly when the light is on at their preferred site, this response does not explain their site preference. (e-f) Same as (a-b), but saccades are grouped according to the time after the bird’s arrival at the target site. Elapsed time does not explain the site preference. (g) Results of a generalized linear model that evaluated each cell’s tuning for gaze location and the state of the viewed light cue (on or off). For each saccade, we counted spikes from −100 to +300 ms, and for each cell used the MATLAB function fitglme with a log link function and Poisson distribution. Very few cells (5.2%, 131/2524 with a statistical threshold of p = 0.05, two-sided log-likelihood ratio test) were tuned to the indicator light without also being location-tuned. (h) Same as (g), but for the 278 cells that had place and gaze selectivity of >0.5. Only one cell was significantly light-tuned without also being location-tuned.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Distribution of place fields in the arena.

(a) Example place maps for neurons that had firing fields at various locations along the path of the bird. In order to match the conventional way place cells are analyzed in the literature, spikes are not shifted by the optimal time lag for each neuron. Otherwise, the maps are plotted as in Fig. 1c. (b) Distribution of place field locations for all place cells (left) and only cells with place and gaze selectivity >0.5 (right). Place field location was defined as the location of the maximum firing rate for each cell. The first and last bin of the histogram are over-represented because the maximum was measured on a truncated segment of the arena between the central site and the target. Although more cells have place fields closer to the target than to the center, there are many cells with place fields far from the target that have significant gaze coding (right).

Extended Data Fig. 7 All-to-all task to disambiguate gaze target from the bird’s location.

(a) Activity in the All-to-all task, where the chickadee was located at one of five sites and gazing at one of the other sites. After this visual search period, the chickadee dashed directly from one site to another. The location of the bird prior to the dash was the “source”, while the target of gaze and the endpoint of the dash was the “target”. Activity of each cell is shown during dashes (“Place”, left) and during gaze fixations (“Gaze”, right). Firing rates are calculated as a function of either the target site (top) or the source site (bottom). Included are cells with place and gaze selectivity (>0.67), either for the target or the source, and with baseline-subtracted response > 0.5 Hz. Each row is normalized from 0 (blue) to maximum (yellow) across target and source measurements, separately for place and gaze. (b) Correlation of the tuning curves for place and gaze (i.e. the rows of the matrices in (a)). Top: correlation of target tuning curves; bottom: correlation of source tuning curves. In both cases, correlations for actual data are higher than for a shuffled distribution, in which cell identities were scrambled. (c) Comparison of selectivity for target and for source. Selectivity for each neuron was measured by subtracting the mean of the five values in its tuning curve from the maximum of those five values. For both place (left) and gaze (right), selectivity is higher for the target than for the source.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Early peak during gaze fixations partly predicts the upcoming gaze.

(a) Coefficients of a linear mixed effects model that fit the early response (at +17 ms relative to saccade peak) as a function of eight behavioral variables (fixed effects), and allowed the intercept to vary for each cell (random effect). Four of the variables accounted for the gaze fixation preceding the saccade, and the other four accounted for the gaze fixation following the saccade. For the previous and next fixation, variables included the horizontal and vertical deviations from the target (which could be positive or negative), as well as the squared values of these deviations. Included are cells with place and gaze selectivity >0.5 (n = 278 cells). Asterisks indicate significant coefficients (p < 10−9 for all, p-value for the t-statistic of the hypothesis that the corresponding coefficient is different from zero, returned by MATLAB function fitlme. We then adjusted each p-value for multiple comparisons using a Bonferroni correction). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals for the coefficient estimates. The key conclusion is that the early response depended on the location of the next fixation. (b) Same as Fig. 3h, but only including trials where the previous fixation was 30–40° from the preferred target. Note that the early response still depends on the bird’s expectation of the light turning on, even though the previous fixation is clamped in the same narrow range of angles for all conditions. Due to the small subset of trials, the number of included cells is now smaller than in Fig. 3h (n = 387, 377, and 364 cells for the black, blue, and pink traces). (c) Coefficients of a model that fit the early response in the Blocked-trial task and included variables for whether the chickadee should expect the light to turn on in the trial, separately for catch and non-catch trials. In both cases, coefficients corresponding to these variables were significantly non-zero (* indicates p < 0.05, calculated as in panel (a)), indicating that the early response predicted whether the light would turn on. For (c), included cells were the same as in Fig. 3h (n = 402 cells).

Extended Data Fig. 9 Classification of cell types in the chickadee hippocampus.

(a) All recorded units plotted according to their mean firing rate across the session and two features of spike waveforms shown in the diagram. These measurements separate putative excitatory (pink) from putative inhibitory (blue and teal) cells. Inhibitory cells are further classified by their responses during saccades (Fig. 4) into Peak (blue) and Trough (teal) types; these types show some systematic differences in firing rate and spike waveforms. (b) Average spike waveforms of three example cells, one from each of the categories shown in (a).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Video 1

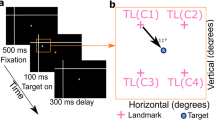

Example of behaviour and neural recording. Rendering of the chickadee’s head position and angle from an actual behavioural session. Cones: projected gazes of the two eyes ±10°; ipsi and contra indicate gazes of eyes ipsilateral and contralateral to the neural recording, which was in the left hippocampus in this bird. In each trial, one of the four outer sites was randomly chosen as the reward site. An indicator light (white ring) turns on at that site if the bird gazes at it with either eye. The video shows two trials: one in which site 1 was the reward site and another in which site 2 was the reward site. Between these two trials, the chickadee made an error and dashed towards site 4. Cyan dots: spikes fired by a recorded neuron during gaze fixations from the central site, plotted at the location of the estimated gaze. Red dots: spikes fired by the same neuron during navigation (that is, dashes from the centre towards outer targets), plotted at the bird’s current location. The neuron was selective for site 1; it fired whenever the bird dashed towards site 1 or gazed at site 1 with the contralateral eye. Note that the rendering of the chickadee’s head was enlarged by approximately ×1.6 for visualization purposes.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Payne, H.L., Aronov, D. Remote activation of place codes by gaze in a highly visual animal. Nature 643, 1037–1043 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09101-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09101-z