Abstract

Cognitive processes underlying behaviour are linked to specific spatiotemporal patterns of neural activity in the neocortex1,2,3,4,5,6. These patterns arise from synchronous synaptic activity7 and are often analysed as oscillations, but may also display aperiodic dynamics that are not well detected. Here we develop a novel analytical method decomposing patterned activity into discrete network events and use this approach to track gamma activity (30–80 Hz) in the mouse visual cortex (V1). We find that the gamma event rate varies with arousal and individual events can cluster in brief oscillatory bouts but also occur in isolation. Individual events synchronize neural firing across layers and promote enhanced visual encoding. V1 gamma events are evoked by patterned input from the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN) and suppressed by optogenetic modulation of the dLGN, suggesting that they support thalamocortical integration of visual information. In behaving mice, the gamma event rate increases steadily before visually cued behavioural responses, predicting trial-by-trial performance. Suppressing V1 gamma events impairs visual detection performance, whereas evoking them elicits a behavioural response. This relationship between gamma events and behaviour is sensory modality specific and rapidly modulated by changes in task objectives. Gamma events thus support a flexible encoding of visual information according to behavioural context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Neural activity in the neocortex exhibits complex spatial and temporal patterns that dynamically reflect changes in behavioural state and task engagement4,8,9,10,11,12. Moreover, disrupted activity patterns are a hallmark of many neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders13,14. Activity patterns in the cortical local field potential (LFP) arise largely from synaptic currents in local neuronal circuits7. High-frequency activity, particularly in the gamma band (30–80 Hz), is linked to cognitive processes including attention, perception and memory15,16. This activity is generally thought to correspond to oscillations4,8,9,17,18 that arise from local interactions between excitatory and inhibitory neurons8,9,19,20,21,22,23 and gate incoming signals8,24,25, facilitating transmission to output structures24,26. However, this framework does not account for some key observations of cortical activity25,27,28,29,30,31 and the mechanisms by which local oscillators may support communication between areas remain unclear32,33,34.

Patterned cortical activity may instead represent repeated individual network events that are difficult to precisely and reliably detect using standard methods. In addition, bouts of patterned activity can also reflect dynamic interactions between cortical layers35, but their spatial structure is rarely quantified. Establishing comprehensive links between patterns of cortical activity and behaviour thus requires novel approaches to detect and quantify discrete network events with a consistent spatiotemporal profile during dynamically regulated cortical activity.

To examine whether patterned cortical activity represents a series of discrete network events, we recorded LFPs across cortical layers in V1 of freely running head-fixed mice (Fig. 1a,b) and developed an analytical method for clustering band-limited activity by state and spectrotemporal feature (CBASS; Methods, Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Information). CBASS combines ideas from previous work and seeks to identify recurring patterns of activity having consistent dynamics across channels36,37 while specifically examining single cycles within specific frequency bands31,38. Crucially, CBASS considers single events and can thus detect neural processes that exhibit varying periodicity29 ranging from distributed individual events to transient or sustained oscillations28,39,40. Candidate events having energy within a specific frequency band in a reference channel are isolated, and events whose laminar and temporal profile is consistent across channels and enriched during specific target states are retained (Methods, Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 1).

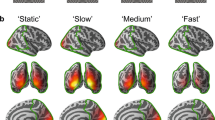

a, Schematic of laminar V1 recordings in head-fixed mice on a running wheel. b, Example data showing one LFP channel and its short-time Fourier transform during a transition from quiescence to locomotion (purple). a.u., arbitrary units. c, Average LFP power across channels (n = 19 mice), showing a selective power increase in the gamma range (30–80 Hz) during locomotion. d, CBASS applied to data from V1 during locomotion. The multichannel LFP (black) is filtered in the gamma (30–80 Hz) range. Candidate events are selected at the troughs of the filtered signal in a reference channel, and events (orange bars) whose phase and amplitude profile across channels predicts locomotion are retained. e, Average LFP around gamma events (left) and the associated CSD profile (right). Events are associated with a propagation of activity from layer 4 to superficial layers, followed by deep layers. Orange dashed line denotes gamma event. f, Rate of CBASS-detected gamma events around locomotion onset (L-on; n = 19 mice). g, Event rate increases during locomotion (L; n = 19 mice). Q, quiescence. h, Average distribution of inter-event intervals for gamma events. Events are divided into three groups: (1) burst, events whose closest neighbour is within 27.3 ms (1.5 average cycle); (2) distributed, events whose closest neighbour is further than 27.3 ms but within 90.9 ms (5 average cycles); and (3) isolated, events whose closest neighbour is further than 90.9 ms (n = 19 mice). The expanded view of the ‘isolated’ potion of the plot is also shown (inset). Black dashed lines denote divisions between groups. i, Population average distribution of firing around burst, distributed and isolated gamma events for extracellularly recorded regular-spiking (RS; black; n = 457 units) and fast-spiking (FS; red; n = 260 units) units across layers. Orange dashed line denotes gamma event. j, Average CSD profile of burst, distributed and isolated gamma events (n = 19 mice). Orange dashed line denotes gamma event. The error bars denote the s.e.m; and the shaded areas indicate mean ± s.e.m. For statistical significance, *P ≤ 0.05 and ***P ≤ 0.001. See Supplementary Table 1 for detailed statistics and Supplementary Table 2 for statistical samples.

V1 in the mouse exhibits a selective increase in gamma (30–80 Hz) power during locomotion4,11,17 (Fig. 1b,c), providing a well-defined context in which to examine discrete, repeated cortical network events in behaving animals. CBASS detected gamma events at a sustained rate in V1 of awake mice (average rate of 24.3 Hz; n = 19 mice). Event detection was highly unlikely in randomized data with spectrum and channel covariance matching that of our recordings (Extended Data Fig. 1i–k) but was robust to a change in reference channel (Extended Data Fig. 1n,o). Gamma events could be detected by a simpler method based on an amplitude threshold (Extended Data Fig. 1p,q), suggesting that these events are integral to awake cortical activity. However, CBASS provided more sensitive detection by enforcing consistent dynamics across cortical layers. Together, these results indicate that the CBASS approach provides stable detection of single-cycle network events. All statistical tests and samples are listed in detail in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

The occurrence of gamma events was highly variable across time (Fig. 1d). Nevertheless, the average LFP and current source density (CSD) profile of gamma events remained stable across behavioural state, visual stimulation and variation of instantaneous rate (Fig. 1e,h–j and Extended Data Fig. 2v–ab). The average field around gamma events held energy in the gamma range (Extended Data Fig. 2v) and LFP power in the gamma range increased during periods of high event incidence (Extended Data Fig. 2g). Event rate increased during locomotion (Fig. 1f,g and Extended Data Fig. 2k,l) and was correlated with pupil diameter, a biomarker of arousal (Extended Data Fig. 2m). Gamma events occurred both in oscillatory clusters and as isolated individual events (Fig. 1d,h). Gamma events that occurred in isolation, in distributed groups, or in tight bursts all had similar efficacy in entraining the spikes of V1 neurons (Fig. 1i) and consistent CSD profiles (Fig. 1j). However, the effect of gamma events on the LFP frequency spectrum was dependent on their instantaneous rate (Extended Data Fig. 2z–ab). Isolated events elicited energy across a broad range (30–80 Hz) and grouped events elicited a narrower band (approximately 55 Hz)17, suggesting that epochs of narrow-band and broad-band gamma LFP power17,29,41 represent different outcomes of the same network mechanism.

In addition to gamma associated with locomotion, mouse V1 exhibits other prominent modes of patterned activity, including robust visually modulated beta or low gamma oscillations (15–30 Hz; hereafter referred to as beta)6,42,43. CBASS-detected beta events were modulated by visual stimuli (Extended Data Fig. 2c,d,f,n–q) and had distinct laminar profiles from gamma events, with a stronger activation of deep layers (Extended Data Fig. 2r,s). The beta event rate was not strongly modulated by locomotion or pupil diameter (Extended Data Fig. 2k–m). Beta and gamma events were interleaved on a fast timescale, indicating rapid switching of network processes (Extended Data Fig. 2a,b). However, co-labelling between gamma and beta events was stronger than expected by chance (Extended Data Fig. 2j) and co-labelled events had an intermediate profile (Extended Data Fig. 2s–u). Consistent with recently proposed models6,42,43,44, gamma and beta events may thus engage distinct but interacting excitatory–inhibitory local circuit mechanisms.

Previous work has suggested that cortical gamma activity may be either locally generated by excitatory–inhibitory interactions8,9,19,20 or passively inherited from afferent structures, such as the thalamus17,45. By contrast, we found that individual gamma events in V1 were associated with robust propagation of activity from layer 4 to layers 2–3 and 5 (Fig. 1e,j and Extended Data Fig. 2v–ab), matching the well-characterized profile of an active feedforwards integration of thalamic drive by cortical circuits46,47. To further examine whether cortical gamma events are generated by thalamocortical input, we expressed channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2)8,48 in the dorsal part of the LGN (Methods, Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). dLGN terminals were activated in V1 by patterned trains of 1-ms light pulses. The CSD profile of cortical responses evoked by dLGN terminal stimulation had a strong and significant cosine similarity with that of gamma events (Extended Data Fig. 3s,t) and remained consistent across patterns (Extended Data Fig. 3u–w). Regular trains of dLGN stimulation produced unrealistic, comb-shaped frequency spectra, and Poisson-distributed trains produced a distributed power increase over frequencies29 (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 3p,q). By contrast, pulse trains that replayed the natural temporal distribution of gamma events recorded in V1 (Fig. 1d,h and Extended Data Fig. 2i) selectively evoked increases in the broad-band (30–80 Hz) and narrow-band (approximately 55 Hz) components of cortical gamma activity regardless of the behavioural state (Fig. 2d,e and Extended Data Fig. 3o–r,x–ac). The frequency signature of V1 gamma activity can thus be largely explained by the temporal distribution of gamma events and can be replicated using a straightforwards model29 (Extended Data Fig. 3g–n). We next expressed ChR2 in inhibitory neurons expressing somatostatin (SST) in the thalamic reticular nucleus (TRN) and implanted an optic fibre above the dLGN (see Methods; Fig. 2f and Extended Data Fig. 3c–f). Modulating dLGN activity by activation of SST+ TRN terminals49,50 sharply reduced V1 gamma event occurrence (Fig. 2h–j) and moderately decreased overall gamma power (Fig. 2g) across quiescence and locomotion (Extended Data Fig. 3ad–aj). V1 gamma activity is thus neither generated solely by local circuits nor inherited as oscillations from the dLGN but rather arises through an active integration of dLGN input across cortical layers51,52.

a, Schematic of laminar V1 recordings in mice on a running wheel coupled to optogenetic activation of dLGN terminals. Mice were injected 5–8 weeks before with AAV5-hSyn-hChR2-eYFP in the dLGN. b, Average LFP and associated CSD profile in response to low-intensity dLGN terminal activation in V1 (1 ms at 474 nm at 1–5 mW mm−2) in an example mouse. Blue dotted line denotes light pulse. c, As in b across mice (n = 9 mice). dLGN terminal activation elicits responses consistent with the laminar profile and time course of gamma events. d, Average LFP power across channels outside (dark blue) and during (light blue) dLGN activation (1 ms at 1–5 mW mm−2), showing that regular pulse trains (left; 20 Hz; n = 4 mice) induce comb-shaped frequency spectra, whereas playing back trains with a natural temporal distribution of gamma events (right; n = 9 mice) elicit broad-band (30–80 Hz) and narrow-band (approximately 55 Hz) V1 gamma activity. e, Average power in the gamma range (30–80 Hz) outside (dark blue) and within (light blue) CBASS-distributed dLGN stimulation trains (n = 9 mice). f, Schematic of laminar cortical recordings in V1 in mice on a running wheel coupled to modulation of the dLGN through optogenetic activation of inhibitory terminals from SST+ TRN neurons (474 nm, continuous, at 50 mW mm−2). SST–Cre+ mice were injected 5–8 weeks before with AAV5-DIO-hChr2-eYFP in the TRN and a fibre was implanted above the dLGN. g, Average LFP power across channels outside (grey) and during (green) light delivery (n = 9 mice). h, Example LFP recording showing a decrease in the incidence of gamma events in V1 (orange bars) during light delivery in the dLGN (green) at quiescence. Opto, optogenetics. i, Rate of CBASS-detected gamma events in the V1 around light delivery in the dLGN (n = 9 mice). Black dotted line denotes onset of light pulse. j, Average V1 power in the gamma range (30–80 Hz) during light delivery in the dLGN (n = 9 mice). The error bars denote s.e.m.; the shaded areas indicate mean ± s.e.m.; and horizontal black bars shows statistical significance: *P ≤ 0.05 and ***P ≤ 0.001. See Supplementary Table 1 for detailed statistics and Supplementary Table 2 for statistical samples.

To examine the effect that network gamma events have on individual neurons, we performed whole-cell patch-clamp recordings in cortical layers 2–5 across locomotion and quiescence in awake mice while simultaneously monitoring the LFP across layers (Fig. 3a,b and Extended Data Fig. 4). Gamma event incidence was linked to depolarized ‘up-states’ in cortical neurons (Extended Data Fig. 4t) and coincided with rapid deflections of the membrane potential (Vm)21,41 (Fig. 3b,c and Extended Data Fig. 4c,d,i,j,o,p). Events coincided with increased Vm power across frequencies (Extended Data Fig. 4e,k,q) and a selective increase in Vm–LFP coherence in the gamma band in all layers (Fig. 3d,e and Extended Data Fig. 4f,l,r). Gamma events were precisely timed relative to spiking in all layers and were associated with a marked increase in spike–LFP synchrony in both intracellular (Extended Data Fig. 4g,m,s,u,v) and extracellular (Fig. 3f,g and Extended Data Fig. 5e–n) recordings. Gamma event-associated spikes occurred earliest in layer 4 and latest in layer 2–3, consistent with feedforward thalamocortical processing (Fig. 3f). Synchrony was strongest in layer 2–3 (Fig. 3g and Extended Data Figs. 4v and 5k–n) and markedly enhanced in fast-spiking, putative inhibitory units relative to regular-spiking, putative excitatory units (Extended Data Fig. 5l,o), in good agreement with previous reports8,9,53. The strong entrainment of both regular-spiking and fast-spiking cells by gamma events further suggests that these network events are driven by the dLGN but engage intrinsically resonant local cortical circuits8,9 that may selectively sharpen and propagate signals in the gamma range46,47.

a, Schematic of simultaneous V1 whole-cell patch clamp and laminar recordings. b, Membrane potential of a layer 4 neuron, inverted LFP and gamma events (orange) around locomotion onset (purple). c, Average Vm around gamma events (n = 25 neurons). Black dotted line denotes time of gamma event. d, Coherence spectra of Vm and LFP during (orange) and outside (grey) gamma event cycles (n = 25 neurons). e, Overall gamma coherence (30–80 Hz) during (orange) and outside (grey) gamma event cycles (8 neurons in layer 2–3, 11 neurons in layer 4 and 6 neurons in layer 5). f, Population average distribution of firing around gamma events for extracellularly recorded regular-spiking units in layer 2–3 (green), layer 4 (cyan) and layer 5 (dark blue). g, Overall spike–LFP pairwise phase consistency (PPC) in the 30–80-Hz range, during (orange) and outside (grey) gamma event cycles for regular-spiking units (82 units for layer 2–3, 69 units for layer 4 and 281 units for layer 5). h, Schematic of laminar recordings during retinotopically aligned visual stimulus presentation. i, Schematic of the analysis of spikes occurring during and outside gamma events (top). Example activity of two V1 regular-spiking units before and after stimulus onset, illustrating visually evoked spikes during gamma event cycles (bottom). j, Modulation of firing response to grating stimuli of increasing contrast during (orange) and outside (grey) gamma event cycles (n = 47 regular-spiking units). The error bars denote s.e.m.; and the shaded areas indicate mean ± s.e.m. For statistical significance, *P ≤ 0.05 and ***P ≤ 0.001. See Supplementary Table 1 for detailed statistics and Supplementary Table 2 for statistical samples.

Although the general association between gamma and cognition is well established, the precise role of gamma events in cortical sensory processing remains unclear. Spike–LFP synchrony within gamma event cycles increased greatly during visual stimulation (Extended Data Fig. 5f,l,o). Event occurrence and regular-spiking unit spiking were uncorrelated during spontaneous activity but became correlated during presentation of high-contrast drifting gratings (Extended Data Fig. 6a–f), suggesting that visually evoked spikes occur preferentially during gamma events. We therefore examined visual responses during and outside of gamma events (Fig. 3h,i). We found that visual stimulation evoked almost no modulation of regular-spiking unit firing outside of gamma event cycles (Fig. 3j and Extended Data Fig. 6i). However, evoked firing was strongly enhanced during gamma event cycles, regardless of the behavioural state (Fig. 3j and Extended Data Fig. 6i,k,m). Some visually evoked activity also occurred during beta events, although less selectively (Extended Data Fig. 6g,h). Gamma events thus aggregate visually evoked spiking in cortical neurons.

To examine whether the enhancement of visual encoding by gamma events contributes to sensory guided behaviour, we trained mice in a visual contrast detection task (Methods and Fig. 4a) that shows behavioural state-dependent performance (Extended Data Fig. 7a–g) and relies on V1 (Extended Data Fig. 7h–l). Modulation of dLGN activity with the stimulation protocol that reduced cortical gamma events (Fig. 2f–j) caused a marked decrease in visual detection performance (Fig. 4b–e). Conversely, patterned activation of dLGN terminals in trained animals evoked behavioural responses, measured as an increase in false alarm trials (Extended Data Fig. 7m–r). This effect was sensitive to stimulation intensity and most robust in response to replay of the natural pattern of events detected by CBASS (Extended Data Fig. 7q–r). Together, these data suggest that V1 gamma events support visual integration and are linked to downstream initiation of behavioural responses.

a, Schematic of trial types in the visual detection task. Trial onset is signalled by a tone. If a grating stimulus is displayed, mice can lick to obtain a water reward (hit). Lick responses made in the absence of visual stimulus (false alarm) lead to a time-out. The absence of response during (miss) or outside (correct rejection) stimulus presentation produce no outcome. b, Head-fixed SST–Cre+ mice (n = 7 mice) injected with AAV5-DIO-hChR2-eYFP in the TRN performed the task described in a. On randomly interleaved trials (30%), blue light (570 nm at 50 mW mm−2, continuous) was delivered above the dLGN through a fibre to activate SST+ TRN inhibitory terminals. c, False alarm subtracted hit rate (mean ± s.e.m.) as a function of stimulus contrast during regular trials (grey) and TRN activation (green). A sigmoid function was fitted to the hit rate in each condition (n = 7 mice). TRN activation reduced detection performance. d, False alarm rate (FAR) and hit rate at maximum contrast (RMax; grey) and during V1 inactivation (green). TRN activation increases FAR and reduces RMax (n = 7 mice). e, Contrast at which the hit rate was 50% (C50) on regular trials (grey) and during V1 inactivation (green). TRN activation increases the C50 (n = 7 mice). f, Example chronic recording during task performance showing LFP, gamma events (orange bars), visual stimulus (grey) and correct lick response (blue arrowhead) during the one hit trial. g, Raster plots of gamma event occurrence on 100 randomly selected trials (top) and the average event rate across trials (bottom) aligned to stimulus onset (less than 7.5% contrast; black dashed line and markers) during miss (left) and hit (centre) trials, and to lick response time (blue dashed line and markers) on hit trials (right). h, Population average gamma event rate during task trials (n = 16 mice). i, Schematic of analysis windows for logistic regression of trial outcome. Early stim, 300 ms after stimulus onset; full stim, full visual stimulation; pre-lick, 300 ms before response or average response time for rejection trials; pre-stim, 300 ms before stimulus onset; post-lick, 300 ms after response or average response time for rejection trials. j, Sensitivity (d′) of the regression increases before response time and is highest right after the response (n = 16 mice). k, Model coefficients for gamma (orange) and beta (blue) events (n = 16 mice). l, Deviance increase upon parameter removal for gamma and beta events (n = 16 mice). The error bars denote s.e.m; and the shaded areas indicate mean ± s.e.m. For statistical significance, *P ≤ 0.05 and **P ≤ 0.01. See Supplementary Table 1 for detailed statistics and Supplementary Table 2 for statistical samples.

To further understand the link between gamma events and visual detection behaviour, we recorded V1 activity during task performance with chronically implanted laminar electrode arrays (Fig. 4f). During hit, but not miss, trials, the gamma event rate exhibited a consistent upwards trajectory starting after stimulus onset and peaking around lick response onset (Fig. 4g,h and Extended Data Fig. 8b,g), whereas the beta event rate was unaffected by trial outcome (Extended Data Fig. 8d–f,h). The laminar profile and entrainment of cortical neurons by gamma events remained consistent throughout trials (Extended Data Fig. 9b–m). We performed a logistic regression to predict behavioural responses using gamma and beta event rates in specific time windows around the stimulus and response onsets (Fig. 4i). Prediction accuracy increased as the animal approached the lick response time. Deviance increase, parameter shuffling and coefficient values indicated that the gamma rate was critical for predicting trial-by-trial behaviour (Fig 4j–l and Extended Data Fig. 9n–w). These results were maintained when the analysis was restricted to periods of quiescence, indicating that they were not due to locomotion-associated gamma events (Extended Data Fig. 9x–ab). Whisking did not modulate the gamma event rate, further indicating that the relationship between gamma events and behaviour is not simply the result of motor movements (Extended Data Fig. 8j–m). Gamma rate increases and model predictions were also significant during false alarm trials (Extended Data Figs. 8c,g and 9s–w). Increased gamma event rates therefore anticipate task-relevant behavioural responses.

To test whether the increased gamma rate before behavioural responses was associated with anticipation of obtaining a reward, we trained naive mice to collect free rewards while viewing a grey screen (Fig. 5a). We observed no significant increase in gamma rate in anticipation of lick responses regardless of reward outcome (Fig. 5b,d–g), suggesting that gamma does not encode generic motor responses or reward signals. To examine whether gamma events might instead represent a learned association between visual stimulus conditions and reward, we moved the mice to a new paradigm where reward was given exclusively when the lick response occurred during visual stimulation (Fig. 5a). In this paradigm, the gamma event rate selectively increased leading up to behavioural responses (Fig. 5b,d–g and Extended Data Fig. 10c,d). This modulation was rapid, appearing on the first day of the visual paradigm, and independent of locomotion or arousal state (Fig. 5c,e and Extended Data Fig. 10b–f). Mice were then switched back to the free reward paradigm, leading to immediate loss of the association between gamma and behaviour (Fig. 5b,d–g).

a, Schematics of trial types for the spontaneous (S) reward paradigm and T1. Mice were first trained to obtain the reward freely for 15 days (SPre), then switched to T1, where rewards could only be collected during visual stimuli, for 10 days. Finally, mice were switched back to free rewards (SPost) for 15 days. Laminar V1 recordings were obtained throughout with chronically implanted electrodes. b, From top to bottom: normalized gamma event rate within 300 ms after unrewarded (brown) and rewarded (orange) licks, the proportion of rewarded trials (green), the number of licks (blue), the proportion of time spent running (black) and the pupil diameter (black) for each training day (n = 5 mice). c, Gamma event rate on each unrewarded (brown) and rewarded (orange) trial on day 15 of SPre and day 1 of T1 in an example mouse. d, Normalized gamma event rate within 300 ms after unrewarded (left) and rewarded (right) responses during SPre, T1 and SPost paradigms (n = 5 mice). e, Total number of licks (left), fraction of time spent running (centre) and average normalized pupil diameter (right) over SPre, T1 and SPost paradigms (n = 5 mice). f, Normalized gamma event rate around unrewarded licks (blue) during SPre, T1 and SPost paradigms (n = 5 mice). g, Normalized gamma event rate around rewarded licks (blue) or stimulus onset (black) during SPre, T1 and SPost paradigms (n = 5 mice). Visually cued responses elicit a stronger increase in the gamma event rate than in the visual stimulation alone. The error bars denote s.e.m; and the shaded areas indicate mean ± s.e.m. For significance, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001. See Supplementary Table 1 for detailed statistics and Supplementary Table 2 for statistical samples.

The rapid modulation of gamma event rates with changes in visual contingencies is inconsistent with reinforcement learning, in which association builds up and disappears progressively over time54,55. Because gamma events are linked to visual integration, this rapid modulation could instead indicate that global context drives changes that enhance processing in V1 specifically during visually guided behaviour. Consistent with the latter, we found that rewards given automatically in association with visual stimuli elicited a more modest increase in the gamma rate than rewards given for active responses (Extended Data Fig. 10a,g,h). Furthermore, we observed no increased gamma rate in V1 leading up to correct responses when mice were trained on an auditory task (Extended Data Fig. 10a,i,j), suggesting that nonspecific global arousal or task engagement is not responsible for the rapid modulation of gamma rates. Increased gamma at behavioural response is thus sensory modality specific and sensitive to task context, occurring in V1 selectively when visual information is used to guide behavioural output.

Together, our results highlight an alternative to the predominant approach of processing cortical patterns within an analytical framework selectively adapted to oscillations. Taking advantage of multichannel recordings, we found that treating patterns as series of discrete events with characteristic laminar architecture powerfully captures the fine timescale dynamics of gamma activity in mouse V1. Although gamma events often cluster in tight oscillatory bouts, they also occur at more irregular intervals and this complex time distribution explains their distinctive power spectrum signature. Both isolated and clustered gamma events regulate the spiking of individual neurons, aggregating spikes into short time windows that organize information about visual stimuli. In V1, the gamma event rate is selectively modulated when the animal uses that visual information to perform a task, providing a flexible framework for encoding sensory information according to arousal and behavioural context. Examining neural activity around discrete events can thus provide unique insight into the precise flow of signal propagation through cortical circuits and the functional impact of these network events. Our findings highlight the potential for further development of methods for event-based detection of recurring motifs of cortical activity. Indeed, although CBASS tracks events associated with power increases during a specific state, this approach is currently limited to detecting events when activity motifs are dynamically regulated over time.

Our findings indicate that gamma events in V1 arise from active integration of patterned feedforward thalamocortical input46,47,51. Patterned cortical activity, such as gamma, has generally been thought to arise from local excitatory–inhibitory interactions8,9,21,50,54,55. However, cortical processing involves complex local and long-range circuits56 that include subcortical structures such as the thalamus and both primary and higher-order cortical areas10, and it is unclear how locally generated oscillations may synchronize across different processing stages29,57,58. Our results suggest an alternative process, in which entrainment occurs via brief events of cascading synchrony characterized by a specific alignment of the phase and amplitude of activity31.

Overall, these results provide a unifying framework for previously discordant findings in primates5,32,33,56,57 and rodents25,58,59,60 and point to new avenues of investigation of functional dynamics across cortical areas61,62. Indeed, the mechanisms underlying the complex regulation of gamma event incidence and impact are not yet fully understood. We identified a thalamocortical origin of gamma events, but other processes in mouse V1 may also contribute energy in the gamma range63,64. In addition, the precise role of these network events in shaping downstream visual integration and behavioural responses across contexts remains to be further examined.

Methods

Animals

Male and female C57BL/6 mice were kept on a 12-h light–dark cycle, provided with food and water ad libitum, and housed individually following headpost implants. A subset of mice used for optogenetic experiments were heterozygous for PV-ires-Cre (PV–Cre+; strain 008069, Jackson Laboratory) or for SST-ires-Cre (SST–Cre+; strain 013044, Jackson Laboratory). Mouse cohorts are detailed in Supplementary Table 2. All animals were between 3 and 6 months of age at the time of the experiment. All animal handling and experiments were performed according to the ethical guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Yale University School of Medicine.

Surgery

Mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane (1.5% in oxygen) and maintained at 37 °C for the duration of the surgery. Analgesia was provided with subcutaneous injections of carpofen (5 mg kg−1) or buprenorphine (0.05 mg kg−1). Lidocaine (1% in 0.9% NaCl) was injected under the scalp to provide topical analgesia. Eyes were protected from desiccation with ointment (Puralube, Dechra). The scalp was resected, and the skull was cleaned with betadine. A surgical screw was implanted on the skull between the eyes and nuts were glued to the skull above the bregma suture, allowing the fixation of a headplate with bolts.

For chronic electrophysiology, two craniotomies were performed above V1 on the left hemisphere (approximately 0.15 mm in diameter; 3.75 mm posterior and 2.5 mm lateral from Bregma) and above the cerebellum (0.4 mm diameter; approximately 6 mm posterior from Bregma), respectively. An A16 probe with a CM16 connector (Neuronexus) was lowered into V1. Ground and reference wires were inserted above the cerebellum.

For acute electrophysiology, a circular plastic ring (approximately 2.5 mm in diameter) was glued on the skull above V1. The skull inside the ring was protected with cyanoacrylate.

For optogenetic inactivation of V1 coupled to behaviour, ChR2 was expressed in PV-expressing interneurons as previously described65,66,67,68. Craniotomies were performed in PV–Cre+ mice above V1 (3.75 mm posterior and 2.5 mm lateral from Bregma) on each hemisphere and 1 µl of AAV5-Ef1a-DIO-ChR2-eYFP (Addgene) was injected 300 µm deep at a concentration of approximately 1012 vg ml−1. Optical canulae (Doric Lenses) were positioned above the dura.

For optogenetic activation of dLGN terminals, ChR2 was expressed in dLGN neurons. 150 nl of AAV1-hSyn-hChR2(H134R)-EYP (Addgene) was injected at approximately 1012 vg ml−1 on the left hemisphere 2.3 mm posterior and 2.2 mm lateral from Bregma at a depth of 2.7 mm. Mice were then prepared for acute electrophysiology as described above. Alternatively, an optical canula was positioned above the V1 to stimulate dLGN terminals during behaviour.

For optogenetic modulation of dLGN, ChR2 AAV5-Ef1a-DIO-ChR2-eYFP was injected at approximately 1012 vg ml−1 in the left TRN of SST–Cre+ mice 1.3 posterior and 2.05 mm lateral from Bregma as previously described50. Two 400-nl injections were performed at 3-mm and 2.65-mm depth. An optical canula was then lowered above the dLGN (2.3 mm posterior and 2.2 mm lateral from Bregma at 2.6 mm deep) and the mouse was prepared for acute electrophysiology as described above.

Craniotomies were protected with Gelfoam (Pfizer), and all implants were affixed to the skull with dental cement.

Electrophysiology

Mice were habituated to handling and head fixation for 3–5 days before electrophysiological recordings. For chronic recordings, mice were head fixed on a wheel and their implants were connected to the recording apparatus (DigitalLynx System, Neuralynx). The most superficial contact point was used as a reference.

For acute silicon probe and patch-clamp recordings, a small craniotomy (0.1–0.5 mm in diameter) was performed above V1 under isoflurane anaesthesia. Analgesic was provided as described above and mice were moved back for more than 2 h in their home cage to recover from anaesthesia. Mice were head fixed on the wheel. The ring situated above V1 was filled with saline, an AgCl reference electrode placed in the bath and an A16 probe (Neuronexus) was lowered into V1.

For optogenetic activation of dLGN terminals, an optic fibre, connected to a 470-nm blue photodiode (Thorlabs) was lowered above the dura on the side of the A16 probe. For dLGN inactivation, the fibre was connected directly to a canula implanted above the dLGN allowing the local optogenetic activation of the terminals of TRN neurons expressing SST. Light power was calibrated before each recording.

For patch-clamp recording, a second craniotomy (approximately 0.1 mm in diameter) was made for patch pipettes of less than 0.1 mm from that used for the A16 probe. The ring above the V1 was filled with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (135 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 5 mM HEPES, 1 mM MgCl2 and 1.8 mM CaCl2 (adjusted to pH 7.3 with NaOH)). Glass pipettes (4–6 MΩ) were pulled from borosilicate capillaries (outer diameter of 1.5 mm; inner diameter of 0.86; Sutter Instrument) and filled with an internal solution (135 mM potassium gluconate, 4 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM phosphocreatine, 4 mM MgATP and 0.3 mM Na3GTP (adjusted to pH 7.3 with KOH; osmolarity adjusted to 300 mOsmol)). Pipettes were lowered into the V1 and whole-cell or cell-attached patch-clamp configurations were obtained at a depth ranging from 164 to 742 µm. After achieving intracellular access, a minimum delay of 5 min was included before recording to allow cortical activity to recover normal dynamics. Intracellular recordings were amplified with a Multiclamp 700 B amplifier (Molecular Devices).

In all experiments, pupil11 and facial motion69 were recorded at 10 Hz using an infrared camera (FLIR). LFPs, wheel motion and timing signals for face movies, visual stimulus and behaviour were acquired at a 40-KHz sampling rate.

Visual stimulation and behavioural hardware

Visual stimuli were generated using the Psychtoolbox MATLAB extension70 and displayed on a 17″ × 9.5″ monitor situated 20 cm in front of the animal (visual detection task) or 15 cm from the right eye (all other behavioural tasks; passive visual stimulation). The screen display was linearized, and maximum luminance was adjusted to approximately 140 cd.sr m−2. An iso-luminant grey background was displayed between visual stimuli. Task-related actions were implemented through sensors and actuators interfaced with a microcontroller (Arduino Due; Teensy 3.2) connected to a computer running custom routines in MATLAB. Waterspouts were positioned using a servomotor (Hi-tec). Responses were detected through an optical sensor (Optex-FA), and water delivery was controlled using solenoid valves (Asco). When behaviour was performed during electrophysiological recordings, timing signals for spout movement, response and reward delivery were sent from the microcontroller to analogue ports on the DigitalLynx System (Cheetah Software versions 5.6.0, 5.7.4 and 6.4.2).

Optogenetic stimulation protocol

Optogenetic stimulation was delivered in 2-s trains separated by 3-s inter-stimulus intervals. For dLGN terminal activation, light output was calibrated at approximately 1–5 mW mm−2 and 1-ms pulse trains were either regular (20 Hz), Poisson (λ = 24.3 Hz) or drawn from the inter-event interval distribution of gamma events detected by CBASS (Extended Data Fig. 2i; mean of 24.3 Hz). For dLGN inactivation, light was delivered at approximately 50 mW mm−2 continuously.

Visual stimulation protocol

The visual response of single units was tested using vertical gratings drifting leftwards with a 1-Hz temporal frequency and centred on the receptive field at the recording site. Gratings were presented for 3 s and separated by a 2-s inter-stimulus interval. Unit response properties were investigated at all combinations of 4, 8, 32 and 100% contrasts, 0.01, 0.04, 0.16 and 0.64 cycle per degree spatial frequencies, and 10°, 20°, 40° and 80° diameters (64 combinations total).

Behavioural experiments

For behavioural training, mice were water rationed and maintained between 85% and 88% of their initial weight. Reward consisted of 3 µl water droplets. All visual stimuli were full-screen drifting gratings with a spatial frequency of 0.04 cycle per degree and temporal frequency of 2 Hz and were displayed for 1 s. Auditory stimuli consisted of 2-kHz pure tones. On trials in which mice responded by licking, the stimulus was displayed for an additional 2 s during reward consumption.

Visual detection task

Training was divided into five stages. (1) Mice were first trained to collect water freely from the waterspout. Reward was given at regular intervals. Mice were moved to the next stage when they made 100 responses in a 20-min session. (2) Mice were habituated to the trial structure and to associate reward to high-contrast (100%) visual stimuli. The waterspout was moved within reach, and after a 4-s delay, a pure tone (4 kHz at 200 ms) signalled the onset of a trial. Visual stimuli were displayed after a randomized interval (0.5–1.2 s) and a reward was delivered at stimulus onset. Mice could collect an additional reward if they licked during the visual stimulus. The spout was moved out of reach at the end of trial for an additional interval (1.5–3.5 s). Mice were moved to the next stage after two 30-min sessions. (3) Mice had to lick during visual stimulus presentation (100% contrast) to receive a reward. Mice were moved to the next stage when they responded correctly on more than 80% of trials within a 30-min session. (4) No-go trials were introduced. Stimuli were omitted after the tone on 30% of trials. If animals made a response when stimuli were not present on the screen, the waterspout was moved away, and mice incurred a 10-s timeout. Mice were moved to the next stage when their hit rate was more than 80% and their false alarm rate was less than 20%. Sessions lasted 45 min. (5) Contrast was varied to test psychophysical performance. Task structure was otherwise identical to stage 4.

Visual detection and optogenetics

Mice were trained on the visual detection task until stage 5. After 2–5 days on stage 5, optogenetic stimulation was delivered on 30% of trials through an insulated multimode optical fibre (200 µm in diameter, 0.53 NS, Thorlabs) coupled to a 473-nm solid-state laser (Opto Engine) or through a 470-nm photodiode (Thorlabs). Pulse timing was controlled through transistor-transistor logic (TTL) pulses or a shutter (Thorlabs). Stimulation started 300 ms before stimulus onset and was maintained until the end of the trial. To test the role of V1 in task performance on PV–Cre+/0 mice, laser power was adjusted to produce an output of approximately 100 mW mm−2 and 55-ms pulses were delivered at 10 Hz. To test the role of dLGN activation, 1-ms pulses were delivered at an intensity of 3 mW mm−2 or 5 mW mm−2 that were either regular (20 Hz), Poisson (λ = 24.3 Hz) or drawn from the inter-event interval distribution of gamma events detected by CBASS (Extended Data Fig. 2i; mean of 24.3 Hz). To test the role of dLGN inactivation on SST–Cre+/0 mice, light was delivered continuously at an intensity of 50 mW mm−2.

To investigate how the gamma event rate at response time depended on reward contingencies, we used training schedules consisting of combinations of the following paradigms: spontaneous, task 1 visual, task 2 auditory and forced reward.

Spontaneous paradigm

No stimuli were displayed. Mice were given rewards at Poisson-distributed time intervals (λ = 10 s) to ensure a flat hazard rate. Lick responses made at any time led to additional rewards with an 80% probability.

Task 1 visual paradigm

Rewards were given only when lick responses were made during visual stimuli. Stimuli appeared on the screen at Poisson-distributed time intervals (λ = 9 s).

Task 2 auditory paradigm

Rewards were given only when lick responses were made during auditory stimuli (2-kHz pure tone). The task structure was otherwise identical to task 1.

Forced reward paradigm

Rewards were passively given at the onset of visual stimuli. An additional reward was given upon reward collection. The task structure was otherwise identical to task 1.

Training schedules were always initiated with the spontaneous paradigm in mice having no previous experience in behavioural experiments other than habituation to head fixation and handling.

Preprocessing

Data were analysed in MATLAB 2018b (Mathworks) using custom scripts. All time series were downsampled to 2 KHz (patch-clamp recording) or 1 KHz (chronic recordings) and aligned. LFP recordings were high-pass filtered at 1 Hz using a second-order Bessel filter and z-scored across channels. LFP channels were mapped onto cortical layers using the CSD profile of visual responses (Extended Data Fig. 1l). Recordings of membrane potential (Vm) were curated using a custom-made procedure to delineate epochs suitable for processing. Epochs were retained if (1) the spike threshold was within −40 ± 2 mV, (2) the spike peak was above −20 mV, and (3) Vm values outside spikes stayed in the −85 to −40-mV range. Junction potentials were not corrected but were estimated as −14.9 mV as previously described41. For event-triggered averages of Vm, spikes were removed from −2 to 5 ms from peak and missing values were interpolated with cubic splines. Pupil diameter was measured from movies with a custom procedure11. Pupil diameter was normalized to the average pupil diameter during locomotion for comparison between recordings. The first principal component of whisker pad motion energy was computed from the same movie using FaceMap69. Pupil diameter and facial motion were linearly interpolated and aligned to the other time series. Epochs of running and whisking activity were defined using a change point algorithm detecting local changes in the mean and variance of running speed and whisker pad motion11. Briefly, moving standard deviations of speed and facial motion energy were computed with a defined temporal window. The length t of this window determined the temporal resolution of the change-point analysis and was set to 4 s for running speed and 500 ms for facial motion. A first estimate of locomotion or whisker motion onset or offset times were then taken as the time when the moving standard deviations exceeded or fell below 20% of its range above minimum. Estimates were refined in a window t around each onset or offset time by computing the time points corresponding to the maximum of the t-windowed moving forwards or backwards z score.

Single-unit clustering

Single units were extracted from LFP recording using spikedetekt and clustered using klustakwik2 (Python v2.7.16 and NumPy v1.11.3)71. Clusters were visualized and sorted using the phy-gui (https://github.com/cortex-lab/phy; Python v3.11.9 and NumPy v1.26.4) together with a custom MATLAB GUI to compute quality metrics. Single-unit clusters were generally retained if less than 0.2% of inter-spike intervals were inferior to 2 ms and if their isolation distance and L-ratio were superior to 15 and inferior to 0.01, respectively72. Isolation distance and L-ratio are biased by spike number so deviations to those rules were occasionally allowed for units of low firing rate (less than 200 spikes) if their waveform was well above noise.

Fast-spiking and regular-spiking units were defined as previously described11. In brief, the average normalized waveforms of all units were clustered with the k-means method based on two parameters: peak-to-trough time, and repolarization (that is, defined as the value of the normalized waveform 0.45 ms after peak). Fast-spiking units had higher repolarization values and shorter peak-to-trough times than regular-spiking units.

CBASS

CBASS ties a power increase in a defined frequency band (that is, gamma (30–80 Hz)) during a particular state (that is, locomotion) to the occurrence of defined events in the temporal domain. A detailed description is available in the Supplementary Information and implementations in MATLAB and Python are available on GitHub (https://github.com/cardin-higley-lab/CBASS). In brief, the multichannel LFP is filtered in the band of interest and candidate events are selected at the troughs of the filtered signal in a reference channel (Extended Data Fig. 1a,b). The spectrotemporal dynamics underlying each candidate event were parameterized using the real and imaginary part of the analytical representation (MATLAB function hilbert) of the filtered signal in each channel (Extended Data Fig. 1c). Candidate events form a cloud in this parametric space where neighbours have similar spectrotemporal dynamics (Extended Data Fig. 1d). The event cloud was split randomly into n partitions and a binomial test was performed in each partition to determine whether events happened during the state of interest (that is, locomotion) at higher frequencies than overall. Partitioning was repeated N times (Extended Data Fig. 1e). A state enrichment score was calculated for events as the fraction of time they fell into an enriched partition (Extended Data Fig. 1f). An optimization procedure was then applied to find the threshold yielding the most significant distance between events having a low and a high enrichment score in the feature space (Extended Data Fig. 1g). Events above threshold are retained (Extended Data Fig. 1h). Here we used n = 20 partitions and N = 1,000. Different settings for these parameters have only a marginal influence on the result of the procedure.

To check the validity of the event partition, a state enrichment score was computed as described above on surrogate data having a spectrum and channel covariance matched with that of each recording (Extended Data Fig. 1i). These surrogate data were constructed by decomposing the original LFP recording into principal components across channels (MATLAB function pca), randomizing the phase of their Fourier transform and remixing them. The fraction of candidate events above threshold on surrogate data indicates how likely the pattern may be associated to the state of interest (that is, locomotion) given the statistics of the signal (Extended Data Fig. 1j,k).

Layer alignment of LFP and CSD across recordings

To compute the average field potential around CBASS events across recordings, the LFP was linearly interpolated across channels to a common grid of laminar position. The CSD was derived as the second spatial derivative of the LFP across interpolated laminar positions.

Comparison of naturally occurring and evoked gamma events

The similarity between naturally occurring gamma events and responses to 1–5 mW 1-ms optogenetic stimulation of dLGN terminals was quantified for each session by computing the average CSD, respectively, in a −10 to 10-ms and −5 to 15-ms interval around each. Gamma events were excluded if they fell during a train of optogenetic stimuli to avoid overlap. The cosine similarity between the two average CSD was computed as:

Where \({A}_{n}\) and \({B}_{n}\) are the nth elements of the vectorized CSDs. Significance was estimated by repeating this calculation after randomizing the timing of gamma events in each session and testing for differences between the real and randomized cosine similarities across sessions.

Activity within and outside CBASS event cycles

CBASS events are aligned to the trough of the bandpass-filtered LFP in a reference channel. We defined the boundaries of each event as the peaks surrounding the trough of the event. Peak and troughs were determined as the 0 and π valued time points of the argument (MATLAB function abs) of the analytic representation (MATLAB function hilbert). Activity inside the event boundaries thus fell within a cycle centred on the trough. Epochs during and outside all CBASS event cycles were pooled separately and compared.

Correlation

Correlation between average CBASS events rate, pupil diameter, membrane potential or extracellularly recorded unit firing rate was calculated across 200-ms chunks of the data.

Spike distribution around CBASS events

Spike distribution around CBASS events was computed as follows. For a selected unit, the lag separating each spike from the nearest CBASS events was estimated. A histogram of lag values was then computed and normalized by total spike count. Histograms were averaged across units.

Event rate normalization

Normalized rates for CBASS-detected events were calculated as follows. A baseline event rate p was computed over samples. The variance of the rate over a window of n samples was estimated assuming a binomial distribution as \({s}_{n}^{2}=np(1-p)\). The normalized rate of events over a window of n samples was then taken as \({r}_{n}=(r-p)/\sqrt{{s}_{n}^{2}}\) where r is the event rate over samples and can be thought of as the number of standard deviations away from baseline.

Unit firing modulation by visual stimulation

Modulation of single-unit action potential firing by visual stimulation was calculated similarly to the normalized event rate. A baseline firing rate r was computed over samples outside visual stimuli. The variance of the rate over a window of n samples was estimated assuming a binomial distribution as \({s}_{n}^{2}=nr(1-r)\). The modulation of event firing for each stimulus modality samples was then taken as \({r}_{s}=({r}_{{\rm{vis}}}-r)/\sqrt{{s}_{s}^{2}}\) where rvis is the visually evoked firing rate and s is the number of samples within the visual stimulation period. Firing modulation can be thought of as the number of standard deviations away from the mean baseline rate. The baseline firing rate of each unit was computed separately within and outside CBASS event cycles.

Spectral analysis

The spectral power of a given time series was derived with Welch’s method. Each channel was divided into 500-ms overlapping segments (75% overlap). Each segment was multiplied by a Hamming window and their Fourier transform was computed (MATLAB function fft). Power was derived as 10 times log10 of the squared magnitude of the Fourier transform and expressed in dB. Power was averaged over segment and channels.

The spectral power of event-triggered averages was derived with a minimum bias multitaper estimate73. This differs from a classical multitaper estimate in that Slepian tapers were replaced by a sinusoidal taper sequence defined as:

where N is the number of samples in the triggered average, n is the sample number and k is the order of the taper. Sinusoidal tapers produce a spectral concentration almost comparable with that achieved with a Slepian sequence while markedly reducing local bias. The number of tapers was chosen to yield a bandwidth of 0.8 Hz following the formula: \(K={\rm{round}}((4\pi NB/r)-1)\) where B is the bandwidth and r is the sample rate. Triggered averages were multiplied by each taper. Spectral power was then computed as described above and averaged over tapers.

For coherence and spike-phase locking estimation, spectrotemporal representations were first derived either for a set of frequencies using a wavelet transform (MATLAB function cwt) and a Morlet wavelet (MATLAB identifier cmor1-2) or across a full frequency band by computing the analytical representation of the filtered signal (MATLAB function Hilbert). Coherence was defined as:

where Sk(n) is the spectrotemporal representation of signal k for sample n at the frequency f. κf has a positive bias of (1 – κf)/N where N is the number of samples74,75. The bias was subtracted from the estimate. Spike-phase locking was estimated using the PPC76 defined as:

where θk is the phase of the signal for frequency f at the time of spike k and N is the total number of spikes. PPC provides an unbiased estimate of spike-phase locking. However, estimates can be noisy if the spike number is inferior to 250. Thus, population estimates of PPC were derived by pooling spikes from all selected neurons and the variance over neurons was estimated with a leave-one-out Jackknife procedure77.

Logistic regression

Logistic regressions of trial outcome in our visual detection task were performed using the MATLAB function glmfit and a logit transfer function. Logistic regression models return an estimation of the probability of response for each trial. The log-likelihood of regression models was calculated by summing the log-likelihood of the outcome of each trial given the probabilities returned by the model and assuming a Bernoulli distribution. Model performances were tested using likelihood ratio tests and quantified with McFadden’s R2 and a sensitivity metric (d′). McFadden’s R2 was defined as:

where LLmodel represents the log-likelihood of the regression and LL0 represent the log-likelihood of the null model (that is, the likelihood of the data assuming that all trials have an equal probability of success corresponding to the mean hit rate). Sensitivity was defined as

where Z is the inverse standard normal distribution, and Presp and Prej represent the average probability of response returned by the model for response and rejection trials, respectively. The impact of each regressors was assessed in two ways. (1) Regression was recomputed 1,000 times after shuffling the values of the regressor over trials. A P value for the significance of the impact of each regressor was derived as the percentage of R2 on shuffled values superior to the actual R2 of the model. (2) Regression models were compared with a model in which each regressor was taken away and the significance of the contribution of the regressor was estimated with a likelihood ratio test. The magnitude of the contribution of a regressor was measured using the increase in deviance. Deviance represents the difference of predictive power from a saturated model giving a perfect prediction (that is, the likelihood of each trial is 1). It was defined as:

where LLmodel is the log-likelihood of the model and LLsat is the log-likelihood of the saturated model. Significance was estimated separately for each mouse. Statistical significance across mice was assessed by pooling P values using the Fisher’s method.

Statistics and reproducibility

A detailed description of the statistical test in each figure panel and of statistical samples is provided in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Except where otherwise noted, tests were performed using mice as the statistical unit. All t-tests were two-sided Student’s t-tests. When indicated, independent P values derived on individual mice were pooled using the Fisher’s method. Multiple comparisons were corrected using the Benjamini–Yukutieli procedure for false discovery rate78.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The full datasets generated and analysed in this study are available from the corresponding authors on request due to the large volume of data.

Code availability

CBASS is available on GitHub (https://github.com/cardin-higley-lab/CBASS).

References

Womelsdorf, T., Valiante, T. A., Sahin, N. T., Miller, K. J. & Tiesinga, P. Dynamic circuit motifs underlying rhythmic gain control, gating and integration. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 1031–1039 (2014).

Berger, H. Über das elektrenkephalogramm des menschen. Archiv. f. Psychiatrie 87, 527–570 (1929).

Buschman, T. J. & Miller, E. K. Top-down versus bottom-up control of attention in the prefrontal and posterior parietal cortices. Science 315, 1860–1862 (2007).

Niell, C. M. & Stryker, M. P. Modulation of visual responses by behavioral state in mouse visual cortex. Neuron 65, 472–479 (2010).

Fries, P., Reynolds, J. H., Rorie, A. E. & Desimone, R. Modulation of oscillatory neuronal synchronization by selective visual attention. Science 291, 1560–1563 (2001).

Veit, J., Hakim, R., Jadi, M. P., Sejnowski, T. J. & Adesnik, H. Cortical gamma band synchronization through somatostatin interneurons. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 951–959 (2017).

Buzsáki, G., Anastassiou, C. A. & Koch, C. The origin of extracellular fields and currents — EEG, ECoG, LFP and spikes. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 407–420 (2012).

Cardin, J. A. et al. Driving fast-spiking cells induces gamma rhythm and controls sensory responses. Nature 459, 663–667 (2009).

Sohal, V. S., Zhang, F., Yizhar, O. & Deisseroth, K. Parvalbumin neurons and gamma rhythms enhance cortical circuit performance. Nature 459, 698–702 (2009).

Steriade, M. Grouping of brain rhythms in corticothalamic systems. Neuroscience 137, 1087–1106 (2006).

Vinck, M., Batista-Brito, R., Knoblich, U. & Cardin, J. A. Arousal and locomotion make distinct contributions to cortical activity patterns and visual encoding. Neuron 86, 740–754 (2015).

Buzsáki, G. & Wang, X.-J. Mechanisms of gamma oscillations. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 35, 203–225 (2012).

Sohal, V. S. Insights into cortical oscillations arising from optogenetic studies. Biol. Psychiatry 71, 1039–1045 (2012).

Uhlhaas, P. J. & Singer, W. Oscillations and neuronal dynamics in schizophrenia: the search for basic symptoms and translational opportunities. Biol. Psychiatry 77, 1001–1009 (2015).

Wang, X.-J. Neurophysiological and computational principles of cortical rhythms in cognition. Physiol. Rev. 90, 1195–1268 (2010).

Bosman, C. A., Lansink, C. S. & Pennartz, C. M. A. Functions of gamma-band synchronization in cognition: from single circuits to functional diversity across cortical and subcortical systems. Eur. J. Neurosci. 39, 1982–1999 (2014).

Saleem, A. B. et al. Subcortical source and modulation of the narrowband gamma oscillation in mouse visual cortex. Neuron 93, 315–322 (2017).

Fries, P., Roelfsema, P. R., Engel, A. K., König, P. & Singer, W. Synchronization of oscillatory responses in visual cortex correlates with perception in interocular rivalry. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 12699–12704 (1997).

Wang, X. J. & Buzsáki, G. Gamma oscillation by synaptic inhibition in a hippocampal interneuronal network model. J. Neurosci. 16, 6402–6413 (1996).

Tiesinga, P. & Sejnowski, T. J. Cortical enlightenment: are attentional gamma oscillations driven by ING or PING? Neuron 63, 727–732 (2009).

Hasenstaub, A. et al. Inhibitory postsynaptic potentials carry synchronized frequency information in active cortical networks. Neuron 47, 423–435 (2005).

Börgers, C. & Kopell, N. Synchronization in networks of excitatory and inhibitory neurons with sparse, random connectivity. Neural Comput. 15, 509–538 (2003).

Börgers, C. & Kopell, N. Effects of noisy drive on rhythms in networks of excitatory and inhibitory neurons. Neural Comput. 17, 557–608 (2005).

Fries, P. Neuronal gamma-band synchronization as a fundamental process in cortical computation. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 32, 209–224 (2009).

Siegle, J. H., Pritchett, D. L. & Moore, C. I. Gamma-range synchronization of fast-spiking interneurons can enhance detection of tactile stimuli. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 1371–1379 (2014).

Knoblich, U., Siegle, J. H., Pritchett, D. L. & Moore, C. I. What do we gain from gamma? Local dynamic gain modulation drives enhanced efficacy and efficiency of signal transmission. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 4, 185 (2010).

Xing, D. et al. Stochastic generation of gamma-band activity in primary visual cortex of awake and anesthetized monkeys. J. Neurosci. 32, 13873–13880 (2012).

Lundqvist, M. et al. Gamma and beta bursts underlie working memory. Neuron 90, 152–164 (2016).

Perrenoud, Q. & Cardin, J. A. Beyond rhythm — a framework for understanding the frequency spectrum of neural activity. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 17, 1217170 (2023).

Burns, S. P., Xing, D. & Shapley, R. M. Is gamma-band activity in the local field potential of V1 cortex a ‘clock’ or filtered noise? J. Neurosci. 31, 9658–9664 (2011).

Spyropoulos, G. et al. Spontaneous variability in gamma dynamics described by a damped harmonic oscillator driven by noise. Nat. Commun. 13, 2019 (2022).

Ray, S. & Maunsell, J. H. R. Differences in gamma frequencies across visual cortex restrict their possible use in computation. Neuron 67, 885–896 (2010).

Jia, X., Xing, D. & Kohn, A. No consistent relationship between gamma power and peak frequency in macaque primary visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 33, 17–25 (2013).

Schneider, M. et al. A mechanism for inter-areal coherence through communication based on connectivity and oscillatory power. Neuron 109, 4050–4067.e12 (2021).

Douglas, R. J. & Martin, K. A. C. Neuronal circuits of the neocortex. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27, 419–451 (2004).

Principe, J. C. & Brockmeier, A. J. Representing and decomposing neural potential signals. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 31, 13–17 (2015).

MacDowell, C. J. & Buschman, T. J. Low-dimensional spatio-temporal dynamics underlie cortex-wide neural activity. Curr. Biol. 30, 2665–2680 (2020).

Cole, S. R. & Voytek, B. Brain oscillations and the importance of waveform shape. Trends Cogn. Sci. 21, 137–149 (2017).

Sirota, A. et al. Entrainment of neocortical neurons and gamma oscillations by the hippocampal theta rhythm. Neuron 60, 683–697 (2008).

Colgin, L. L. et al. Frequency of gamma oscillations routes flow of information in the hippocampus. Nature 462, 353–357 (2009).

Perrenoud, Q., Pennartz, C. M. A. & Gentet, L. J. Membrane potential dynamics of spontaneous and visually evoked gamma activity in V1 of awake mice. PLoS Biol. 14, e1002383 (2016).

Veit, J., Handy, G., Mossing, D. P., Doiron, B. & Adesnik, H. Cortical VIP neurons locally control the gain but globally control the coherence of gamma band rhythms. Neuron 111, 405–417.e5 (2022).

Chen, G. et al. Distinct inhibitory circuits orchestrate cortical beta and gamma band oscillations. Neuron 96, 1403–1418.e6 (2017).

Onorato, I. et al. Distinct roles of PV and Sst interneurons in visually induced gamma oscillations. Cell Rep. 44, 115385 (2025).

Shin, D., Peelman, K., Lien, A. D., Rosario, J. D. & Haider, B. Narrowband gamma oscillations propagate and synchronize throughout the mouse thalamocortical visual system. Neuron 111, 1076–1085.e8 (2023).

Gabernet, L., Jadhav, S. P., Feldman, D. E., Carandini, M. & Scanziani, M. Somatosensory integration controlled by dynamic thalamocortical feed-forward inhibition. Neuron 48, 315–327 (2005).

Cruikshank, S. J., Urabe, H., Nurmikko, A. V. & Connors, B. W. Pathway-specific feedforward circuits between thalamus and neocortex revealed by selective optical stimulation of axons. Neuron 65, 230–245 (2010).

Boyden, E. S., Zhang, F., Bamberg, E., Nagel, G. & Deisseroth, K. Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1263–1268 (2005).

Reinhold, K., Lien, A. D. & Scanziani, M. Distinct recurrent versus afferent dynamics in cortical visual processing. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1789–1797 (2015).

Hoseini, M. S. et al. Gamma rhythms and visual information in mouse V1 specifically modulated by somatostatin+ neurons in reticular thalamus. eLife 10, e61437 (2021).

Fernandez-Ruiz, A., Sirota, A., Lopes-dos-Santos, V. & Dupret, D. Over and above frequency: gamma oscillations as units of neural circuit operations. Neuron 111, 936–953 (2023).

Cardin, J. A. Snapshots of the brain in action: local circuit operations through the lens of γ oscillations. J. Neurosci. 36, 10496–10504 (2016).

Buffalo, E. A., Fries, P., Landman, R., Buschman, T. J. & Desimone, R. Laminar differences in gamma and alpha coherence in the ventral stream. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 11262–11267 (2011).

Rescorla, R. A. & Wagner, A. R. in Classical Conditioning II: Current Research and Theory (eds Black, A. H. & Prokasy, W. F.) 64–99 (Appleton Century Crofts, 1972).

Watkins, C. J. C. H. & Dayan, P. Q-learning. Mach. Learn. 8, 279–292 (1992).

Bosman, C. A. et al. Attentional stimulus selection through selective synchronization between monkey visual areas. Neuron 75, 875–888 (2012).

Womelsdorf, T. et al. Orientation selectivity and noise correlation in awake monkey area V1 are modulated by the gamma cycle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 4302–4307 (2012).

Shin, H. & Moore, C. I. Persistent gamma spiking in SI nonsensory fast spiking cells predicts perceptual success. Neuron 103, 1150–1163.E5 (2019).

Shin, H., Law, R., Tsutsui, S., Moore, C. I. & Jones, S. R. The rate of transient beta frequency events predicts behavior across tasks and species. eLife 6, e29086 (2017).

Speed, A., Del Rosario, J., Burgess, C. P. & Haider, B. Cortical state fluctuations across layers of V1 during visual spatial perception. Cell Rep. 26, 2868–2874.e3 (2019).

Bastos, A. M. et al. Visual areas exert feedforward and feedback influences through distinct frequency channels. Neuron 85, 390–401 (2015).

Fiebelkorn, I. C. & Kastner, S. A rhythmic theory of attention. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23, 87–101 (2019).

Welle, C. G. & Contreras, D. Sensory-driven and spontaneous gamma oscillations engage distinct cortical circuitry. J. Neurophysiol. 115, 1821–1835 (2016).

Senzai, Y., Fernandez-Ruiz, A. & Buzsáki, G. Layer-specific physiological features and interlaminar interactions in the primary visual cortex of the mouse. Neuron 101, 505–513.E5 (2019).

Lien, A. D. & Scanziani, M. Tuned thalamic excitation is amplified by visual cortical circuits. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 1315–1323 (2013).

Glickfeld, L. L., Histed, M. H. & Maunsell, J. H. R. Mouse primary visual cortex is used to detect both orientation and contrast changes. J. Neurosci. 33, 19416–19422 (2013).

Li, N. et al. Spatiotemporal constraints on optogenetic inactivation in cortical circuits. eLife 8, e48622 (2019).

Babl, S. S., Rummell, B. P. & Sigurdsson, T. The spatial extent of optogenetic silencing in transgenic mice expressing channelrhodopsin in inhibitory interneurons. Cell Rep. 29, 1381–1395.e4 (2019).

Stringer, C. et al. Spontaneous behaviors drive multidimensional, brainwide activity. Science 364, eaav7893 (2019).

Kleiner, M. et al. What’s new in psychtoolbox-3. Perception 36, 1–16 (2007).

Rossant, C. et al. Spike sorting for large, dense electrode arrays. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 634–641 (2016).

Schmitzer-Torbert, N., Jackson, J., Henze, D., Harris, K. & Redish, A. D. Quantitative measures of cluster quality for use in extracellular recordings. Neuroscience 131, 1–11 (2005).

Riedel, K. S. & Sidorenko, A. Minimum bias multiple taper spectral estimation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 43, 188–195 (1995).

Bruns, A. Fourier-, Hilbert- and wavelet-based signal analysis: are they really different approaches? J. Neurosci. Methods 137, 321–332 (2004).

Benignus, V. Estimation of coherence spectrum of non-Gaussian time series populations. IEEE Trans. Audio Electroacoust. 17, 198–201 (1969).

Vinck, M., van Wingerden, M., Womelsdorf, T., Fries, P. & Pennartz, C. M. A. The pairwise phase consistency: a bias-free measure of rhythmic neuronal synchronization. Neuroimage 51, 112–122 (2010).

Shao, J. & Wu, C. F. J. A general theory for Jackknife variance estimation. Ann. Statist. 17, 1176–1197 (1989).

Benjamini, Y. & Yekutieli, D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann. Stat. 29, 1165–1188 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We thank M. J. Higley, D. Lee, N. Schaworonkow and B. Voytek for discussions of the data and manuscript; and all members of the Cardin and Higley laboratories for helpful input throughout all stages of this study. This work was supported by funding from the US National Institutes of Health (EY022951, EY035127 and MH113852 to J.A.C. and EY026878 to the Yale Vision Core), a McKnight Scholar Award (to J.A.C.), an award from the Kavli Institute of Neuroscience (to J.A.C.) and a BBRF Young Investigator Grant (to Q.P.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.P. and J.A.C. designed the experiments. Q.P. and A.H.d.O.F. developed and validated CBASS. Q.P., A.A. and R.M. performed the chronic recordings during a go–no go task. Q.P., A.A. and J.B. performed the behavioural experiments coupled to optogenetic inactivation of the V1. Q.P. performed all other experiments. Q.P. analysed the data. Q.P. and J.A.C. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Antonio Fernandez-Ruiz, Vikaas Sohal and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Flow diagram and validation of the CBASS method.

CBASS links power increases in a frequency band during a particular state to events in the temporal domain. Here we look for events responsible for the power increase in the γ range (30–80 Hz) in mouse V1 cortex during locomotion. a: CBASS uses multichannel time series (black) where the state of interest is indexed (i.e. locomotion, purple). b: The signal is band-pass filtered in the γ range. Candidate events (gray bars) are taken at the trough of the filtered signal in an arbitrary reference channel (red). Here the reference channel is taken as the closest to Layer 4. c: Spectrotemporal dynamics at the time of candidate events are parameterized using the real and imaginary part of the analytical representation (matlab function hilbert) of the filtered LFP in each channel (Supplementary Methods). d: Three dimensional UMAP embedding showing the cloud of candidate events in the parametric space. Events occurring during locomotion (yellow) are present in all regions of the cloud. e: CBASS estimates whether specific spectrotemporal profiles (i.e. regions of the cloud) occur preferentially during locomotion. The cloud is partitioned randomly, and a binomial test is performed in each partition to test if the occurrence of locomotion is higher than overall. This operation is repeated many times (n = 1000). f: A score is derived for each candidate event as the fraction of time it fell into an enriched partition. This score is stronger in regions of the cloud (i.e. event profiles) associated with locomotion. g: CBASS finds the threshold of the enrichment score, maximizing the centroid distance between the cloud of retained and unretained events. h: Retained events (orange) superimposed on the raw data from panel a. i: The validity of the thresholding is tested on surrogate data having the same size, spectral power and covariance matrix across channels as the original data. This data is obtained by decomposing the transform and remixing them (Supplementary Methods). Upper: excerpt of the real (left) and surrogate (right) LFP. Lower: spectral power within (gray) and across channels (orange dotted line) for the real (left) and surrogate LFP (right). j: Distribution of enrichment score for candidate events in real (left) and surrogate (right) data in an example recording. k: Fraction of candidate events above threshold for surrogate data for 200 recording sessions over 19 mice. No candidate event passes threshold for most surrogate sessions. l: Illustration of the methodology used to estimate the laminar position of LFP channels across cortical layers. The average current source density (CSD) of the response to a high-contrast drifting grating stimulus consists of a primary sink in cortical layer four (purple) and a secondary sink occurring at longer latencies in layer 5b (red). This permits a 2-point alignment of a layer boundaries template estimated from histological atlas data. m: Average field potential around γ events (upper), associated CSD activity (middle), and power spectrum (lower) of the average event field (orange) (n = 19 mice). n: Same as m, when choosing the deepest channel as reference (n = 19 mice). o: Upper: average lag between γ events identified with a L4 and a deep reference channel. Lower: cumulative distribution of the lag between γ events identified with a L4 and a deep reference channel. Changing reference channel results in an overall phase shift in retained events (n = 200 session; 19 mice). p: Same as m, when retaining a matching number of events solely based on amplitude across channels. q: Events retained based solely on amplitude have only an 80.60 ± 0.51% overlap coefficient with events retained by CBASS (n = 200 session; 19 mice). Error Bars: s.e.m; shaded areas: mean ± s.e.m. See Supplementary Table 1 for detailed statistics and Supplementary Table 2 for statistical samples.

Extended Data Fig. 2 CBASS links V1 β power increase during visual stimulation to network events distinct from γ events.