Abstract

Controlling quantum matter with light offers a promising route to dynamically tune its many-body properties, ranging from band topology1,2 to superconductivity3. However, achieving such optical control for strongly correlated electron systems in the steady state has remained elusive. Here we demonstrate optical switching of the spin–valley degree of freedom of itinerant ferromagnets in twisted MoTe2 (t-MoTe2) homobilayers. This system uniquely features flat valley-contrasting Chern bands and exhibits a range of strongly correlated phases at various moiré lattice fillings, including Chern insulators and ferromagnetic metals4,5,6,7. We show that the spin–valley orientation of all of these phases can be dynamically reversed by resonantly exciting the exciton–polaron8 transitions with circularly polarized light. These findings not only provide direct evidence for non-thermal optical switching of a ferromagnetic spin state at zero magnetic field but also demonstrate the possibility of dynamical control over a topological order parameter, paving the way for optical generation of chiral edge modes and topological quantum circuits.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the ETH Research Collection: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-c-000784681.

References

Wang, Y. H., Steinberg, H., Jarillo-Herrero, P. & Gedik, N. Observation of Floquet-Bloch states on the surface of a topological insulator. Science 342, 453–457 (2013).

Mitra, S. et al. Light-wave-controlled Haldane model in monolayer hexagonal boron nitride. Nature 628, 752–757 (2024).

Fausti, D. et al. Light-induced superconductivity in a stripe-ordered cuprate. Science 331, 189–191 (2011).

Cai, J. et al. Signatures of fractional quantum anomalous Hall states in twisted MoTe2. Nature 622, 63–68 (2023).

Zeng, Y. et al. Thermodynamic evidence of fractional Chern insulator in moiré MoTe2. Nature 622, 69–73 (2023).

Xu, F. et al. Observation of integer and fractional quantum anomalous Hall effects in twisted bilayer MoTe2. Phys. Rev. X 13, 031037 (2023).

Park, H. et al. Observation of fractionally quantized anomalous Hall effect. Nature 622, 74–79 (2023).

Sidler, M. et al. Fermi polaron-polaritons in charge-tunable atomically thin semiconductors. Nat. Phys. 13, 255–261 (2017).

Kastler, A. Quelques suggestions concernant la production optique et la détection optique d’une inégalité de population des niveaux de quantifigation spatiale des atomes. Application à l’expérience de Stern et Gerlach et à la résonance magnétique. J. Phys. Radium 11, 255–265 (1950).

Brossel, J., Kastler, A. & Winter, J. Gréation optique d’une inégalité de population entre les sous-niveaux Zeeman de l’état fondamental des atomes. J. Phys. Radium 13, 668 (1952).

Meier, F. & Zakharchenya, B. P. (eds) Modern Problems in Condensed Matter Sciences, Vol. 8: Optical Orientation (North-Holland, 1984).

Yale, C. G. et al. All-optical control of a solid-state spin using coherent dark states. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 7595–7600 (2013).

Bodey, J. H. et al. Optical spin locking of a solid-state qubit. npj Quantum Inf. 5, 95 (2019).

Pershoguba, S. S. & Yakovenko, V. M. Optical control of topological memory based on orbital magnetization. Phys. Rev. B 105, 064423 (2022).

Zhang, P. et al. All-optical switching of magnetization in atomically thin CrI3. Nat. Mater. 21, 1373–1378 (2022).

Alebrand, S. et al. Light-induced magnetization reversal of high-anisotropy TbCo alloy films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 162408 (2012).

Lambert, C.-H. et al. All-optical control of ferromagnetic thin films and nanostructures. Science 345, 1337–1340 (2014).

Igarashi, J. et al. Engineering single-shot all-optical switching of ferromagnetic materials. Nano Lett. 20, 8654–8660 (2020).

Yu, R. et al. Quantized anomalous Hall effect in magnetic topological insulators. Science 329, 61–64 (2010).

Chang, C.-Z. et al. Experimental observation of the quantum anomalous Hall effect in a magnetic topological insulator. Science 340, 167–170 (2013).

Yasuda, K. et al. Quantized chiral edge conduction on domain walls of a magnetic topological insulator. Science 358, 1311–1314 (2017).

Yeats, A. L. et al. Local optical control of ferromagnetism and chemical potential in a topological insulator. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 10379–10383 (2017).

Rosen, I. T. et al. Chiral transport along magnetic domain walls in the quantum anomalous Hall effect. npj Quantum Mater. 2, 69 (2017).

Wu, F., Lovorn, T., Tutuc, E., Martin, I. & MacDonald, A. H. Topological insulators in twisted transition metal dichalcogenide homobilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 086402 (2019).

Li, H., Kumar, U., Sun, K. & Lin, S.-Z. Spontaneous fractional Chern insulators in transition metal dichalcogenide moiré superlattices. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, L032070 (2021).

Devakul, T., Crépel, V., Zhang, Y. & Fu, L. Magic in twisted transition metal dichalcogenide bilayers. Nat. Commun. 12, 6730 (2021).

Anderson, E. et al. Magnetoelectric control of helical light emission in a moiré Chern magnet. Phys. Rev. X 15, 031057 (2025).

Neupert, T., Santos, L., Chamon, C. & Mudry, C. Fractional quantum Hall states at zero magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 236804 (2011).

Regnault, N. & Bernevig, B. A. Fractional Chern insulator. Phys. Rev. X 1, 021014 (2011).

Han, T. et al. Correlated insulator and Chern insulators in pentalayer rhombohedral-stacked graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 181–187 (2024).

von Klitzing, K., Dorda, G. & Pepper, M. New method for high-accuracy determination of the fine-structure constant based on quantized Hall resistance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 494–497 (1980).

Arovas, D., Schrieffer, J. R. & Wilczek, F. Fractional statistics and the quantum Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 53, 722–723 (1984).

von Klitzing, K. The quantized Hall effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 58, 519–531 (1986).

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Colloquium: Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010).

Gilbert, M. J. Topological electronics. Commun. Phys. 4, 70 (2021).

Anderson, E. et al. Programming correlated magnetic states with gate-controlled moiré geometry. Science 381, 325–330 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. Fractional Chern insulator in twisted bilayer MoTe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 036501 (2024).

Smoleński, T., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T., Kroner, M. & Imamoğlu, A. Spin-valley relaxation and exciton-induced depolarization dynamics of Landau-quantized electrons in MoSe2 monolayer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 127402 (2022).

Ciorciaro, L. et al. Kinetic magnetism in triangular moiré materials. Nature 623, 509–513 (2023).

Sung, J. et al. An electronic microemulsion phase emerging from a quantum crystal-to-liquid transition. Nat. Phys. 21, 437–443 (2025).

Back, P. et al. Giant paramagnetism-induced valley polarization of electrons in charge-tunable monolayer MoSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 237404 (2017).

Anderson, E. et al. Trion sensing of a zero-field composite Fermi liquid. Nature 635, 590–595 (2024).

Glazov, M. M. et al. Intervalley polaron in atomically thin transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 100, 041301 (2019).

Song, Y., Chalaev, O. & Dery, H. Donor-driven spin relaxation in multivalley semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 167201 (2014).

Uto, T. et al. Interaction-induced ac Stark shift of exciton-polaron resonances. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 056901 (2024).

Evrard, B. et al. ac Stark spectroscopy of interactions between moiré excitons and polarons. Phys. Rev. X 15, 021002 (2025).

Awschalom, D. D. & Kikkawa, J. M. Electron spin and optical coherence in semiconductors. Phys. Today 52, 33–38 (1999).

Cao, Y. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 43–50 (2018).

Cao, Y. et al. Correlated insulator behaviour at half-filling in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 80–84 (2018).

Zomer, P. J., Guimarães, M. H. D., Brant, J. C., Tombros, N. & van Wees, B. J. Fast pick up technique for high quality heterostructures of bilayer graphene and hexagonal boron nitride. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 013101 (2014).

Smoleński, T. et al. Signatures of Wigner crystal of electrons in a monolayer semiconductor. Nature 595, 53–57 (2021).

Chang, X. et al. Evidence of competing ground states between fractional Chern insulator and antiferromagnetism in moiré MoTe2. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.13213 (2025).

Kwan, Y. H. et al. Textured exciton insulators. Phys. Rev. B 112, 035129 (2025).

Popert, A. et al. Optical sensing of fractional quantum Hall effect in graphene. Nano Lett. 22, 7363–7369 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) under grant number 200021-204076. E.A., W.L. and X.X. were supported by the US DOE BES (DE-SC0012509) and Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship (award number N000142512047). K.W. and T.T. acknowledge support from the JSPS KAKENHI (grant numbers 21H05233 and 23H02052), the CREST (JPMJCR24A5), JST and World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI), MEXT, Japan. We thank C. Kuhlenkamp, M. Knap, H. Adlong, A. Christianen and L. Zheng for insightful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.S. designed the experiments and carried out initial observations. T.S. and A.I. supervised the project. O.H., K.K. and T.S. performed the measurements and analysed the experimental data, with assistance from M.K., E.A., W.L. and X.X. W.L. and E.A. fabricated the samples. K.W. and T.T. provided bulk hBN crystals. T.S., O.H. and A.I. wrote the manuscript, with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Xiangbin Cai and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

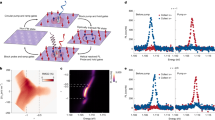

Extended Data Fig. 1 Schematic of the experimental set-up.

For our optical measurements, the light is sent to the sample through the excitation arm, whereas the reflected or emitted signal is collected in the detection arm. All of the lenses are aspheric. BS, beamsplitter; CCD, charge-coupled device used for imaging the sample; LP, linear polarizer; λ/2: half-wave plate; λ/4, quarter-wave plate.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Magnetic-field-dependent PL measurements of device A.

a, Evolution of the PL signal with n at B = 0 T. Cusps corresponding to ICI and FCI states at filling factors ν = −1 and ν = −2/3 are clearly visible. b,c, Evolution of the central energy of a non-dispersive Lorentzian fit to the trion peak in the PL signal with n for B ≥ 0 up to 7 T (b) and B ≤ 0 down to −7 T (c). The grey lines are guides for the eye following the B-dependent cusps and the colour of the line at a fixed B matches that of the corresponding dots in d and e. d,e, Evolution of the cusp charge density with magnetic field for the ICI state at ν = −1 (d) and the FCI state at ν = −2/3 (e). The cusp position for each B was determined using the maximum of the first derivatives of the peak energy with respect to n. The Chern numbers extracted on the basis of the fitted Streda formula at ν = −1 yield C = −1.01 ± 0.05 and C = 0.94 ± 0.08 for ν = −1 at positive and negative B, respectively. At ν = −2/3, the determined Chern numbers are C = −0.63 ± 0.06 (B ≥ 0) and C = 0.62 ± 0.04 (B ≤ 0).

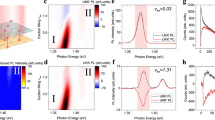

Extended Data Fig. 3 Nearly resonant PL measurement performed with WL excitation in cross-circular polarization setting in device A.

a, PL measurement as a function of charge density n at B = 0 performed using approximately 250-nW PL excitation at 1,090 nm combined with further, resonant, circularly polarized 120-nW WL excitation centred around the AP resonance (about 5 meV FWHM, used for optical spin orientation). b, Trion peak energies extracted from non-dispersive Lorentzian fits to the PL spectra, plotted as a function of charge density n for various magnetic fields B. The cusps observed at filling factors ν = −1 and ν = −2/3 disperse according to the Streda formula, confirming that ICI and FCI states remain robust under circularly polarized WL excitation used for optical spin orientation. The extracted Chern numbers are C = −0.99 ± 0.07 for the ν = −1 state and C = −0.63 ± 0.03 for the ν = −2/3 state.

Extended Data Fig. 4 PL measurement performed after optical spin orientation.

a, Circular-polarization-resolved reflectance contrast spectra showing AP resonance before optical orientation, with the state initialized at B = −120 mT. b, Similar spectra acquired after the optical spin orientation, performed at B = 0. c, PL measurement performed as a function of n at B = 0 after the optical orientation was completed. The cusps corresponding to the incompressible states at ν = −1 and ν = −2/3 states are visible. d, Trion peak energies extracted from non-dispersive Lorentzian fits to the spectra, plotted as a function of charge density n for various magnetic fields B. The cusps observed at filling factors ν = −1 and ν = −2/3 disperse according to the Streda formula, confirming that ICI and FCI states remain robust after optical spin orientation. The extracted Chern numbers are C = −1.04 ± 0.04 for the ν = −1 state and C = −0.65 ± 0.04 for the ν = −2/3 state.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Spin–valley polarization around ν = −1 after optical spin orientation of the ICI state.

a,b, Circular-polarization-resolved reflectance contrast spectra showing the AP resonance before optical orientation, with the state initialized at B = −120 mT (a), and after optical spin orientation, performed at B = 0 (b). c, Spin–valley polarization of the hole system measured as a function of charge density around ν = −1 after optical spin orientation. The data clearly demonstrate that slight underdoping and overdoping of the optically oriented ICI state does not compromise its complete spin–valley polarization.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Schematic of the pump–probe procedure used for optical orientation.

a, The power of the light with about 5 meV FWHM centred on the AP resonance is modulated in time using a fibre optical attenuator. The pump (probe) pulse lasts 3 s (10 s). b, During each pump sequence, the light polarization is set to the desired setting (σ+, σ− or π). During the probe sequence, the excitation is linearly polarized. c, The polarization in the detection path is set to σ− for the initial 5 s of the probe sequence and switched to σ+ for the second half of the probe sequence, allowing us to resolve the hole spin polarization.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Optical spin orientation as a function of excitation power and temperature for ν = −1 and ν = −0.8.

a, For the ICI at ν = −1, efficient optical spin orientation is maintained up to 5 K, although higher excitation powers are required for increasing base temperatures. Between 5 and 7 K, the spin orientation becomes ineffective. b, For the ferromagnetic metal at ν = −0.77, optical spin orientation remains effective up to 1.1 K. Above this temperature, the orientation becomes partial at 1.4 K and is no longer observed at higher temperatures.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Excitation-energy dependence of the optical Chern number orientation.

a–d, Reflectance contrast spectra differentiated with respect to photon energy as a function of displacement field D at a filling factor of ν = −2/3 (a) and ν = −1 (b–d). The spectra were acquired under B = 50 mT in two circular polarizations (σ+: top panels, σ−: bottom panels) using a weak, linearly polarized broadband white-light excitation. Horizontal lines indicate the displacement fields at which the optical switching efficiency is investigated below. e–g, Degree of spin polarization of the AP resonance before (grey circles) and after (coloured circles) illuminating the sample with a narrow-bandwidth (<1 meV FWHM) pump beam as a function of the pump centre wavelength. The wavelength dependence is investigated at the filling factors and displacements fields indicated in the respective reflectance contrast plots above. The pump powers are 90 nW (e), 80 nW (f), 65 nW (g) and 50 nW (h), respectively. In each graph, the spins are first oriented using B = 50 mT, which is then turned off. The spin polarization before and after optical pumping is examined by measuring the helicity-resolved reflection of a linearly polarized white-light probe beam. We pump with σ− (blue circles) and σ+ (red circles) circularly as well as with linearly polarized light (pink circles in g). The spin polarization is inferred by fitting double Lorentzian spectral profiles to the optical resonances in the σ+-polarized and σ−-polarized reflection contrast spectra. The fit parameter corresponding to the amplitude of the stronger Lorentzian is constrained from below and above to reduce fitting uncertainty and an amplitude of zero is assigned to a spectrum when the χ2 of the fit exceeds a global tolerance, that is, when no Lorentzian with a finite amplitude can sensibly be fitted.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Dependence of optical spin switching on pump wavelength and power at ν = −1 and D = 0.

a, Normalized spectra of the pump and probe beams. The centre wavelength of the pump beam can be tuned from 1,080 to 1,125 nm while keeping the output power constant. b–i, Degree of spin–valley polarization of hole system ⟨Sz⟩ at ν = −1 before (grey circles) and after pumping for approximately 5 s with σ+ (red circles) or σ− (blue circles) circularly polarized light at pump powers Ppump between 10 and 510 nW. Before taking each data point, the system is spin-polarized by applying a magnetic field of 50 mT and ramping it back down to zero. The data are analysed as described in the caption of Extended Data Fig. 8.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Optical spin orientation using broadband excitation for device B.

Magnetic hysteresis loop measured at ν = −1 using σ+-polarized and σ−-polarized light with 100 nm power and broad bandwidth spanning from about 1,030 to about 1,120 nm. Even though the hysteresis shows slight dependence on the helicity of the exciting beam, the spin–valley degree of freedom cannot be optically flipped at B = 0, in contrast to the case of narrowband excitation exploited in the main text.

Extended Data Fig. 11 Optical writing of topological edge modes at ν = −2/3 in device A.

a, AP resonance detected with σ− and σ+polarization when the system has been initialized with holes in the K+ valley by applying a finite magnetic field. b, AP resonance detected with σ− and σ+ polarizations after resonant, σ−-polarized excitation with 120 nW excitation power. The vertical dashed lines indicate the optical spot in which the optical spin orientation has been performed.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Information sections 1–5 (including Supplementary Figures 1–7), which provide additional experimental details such as optical spot size determination, stability of the spin states after optical orientation, and the results obtained on another device (device B).

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Huber, O., Kuhlbrodt, K., Anderson, E. et al. Optical control over topological Chern number in moiré materials. Nature 649, 1153–1158 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09851-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09851-w