Abstract

Earth’s early mantle probably existed as a deep, vigorously convecting magma ocean, and its solidification is considered central to the long-term chemical and dynamical evolution of the planet. Yet a notable uncertainty is the grain size of bridgmanite—the dominant lower-mantle phase—whose nucleation behaviour at extreme pressure has remained experimentally inaccessible. Here we show, using a combination of cutting-edge techniques, including large-scale molecular dynamics simulations consisting of up to 1 million atoms driven by machine learning potentials (MLPs), seeding and enhanced sampling, that crystal–melt interfacial energies of MgSiO3 bridgmanite increase substantially with pressure, surpassing those of silicate–liquid systems at ambient pressure by a factor of up to ten (refs. 1,2,3). In a deep basal magma ocean (BMO), this amplified interfacial energy, combined with the potential sluggish cooling, may permit the formation of unusually large bridgmanite crystals, up to centimetre-to-metre-scale sizes. Such potentially large crystals could drive efficient fractional crystallization and cause substantial chemical differentiation and mantle compaction. If operative, this mechanism would provide a new physical pathway linking lower-mantle material properties to early Earth stratification and it motivates future geodynamic models that explicitly incorporate supercooling, compositional convection and elemental partitioning. Our findings thus offer a plausible hypothesis connecting microscopic nucleation processes with macroscopic planetary structure, refining present views of how the Earth’s interior acquired its initial compositional architecture.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The main data supporting the findings of this study are available in the paper and its Supplementary Information. The raw data used to train the machine learning potential of olivine are stored in the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/kf9wb/ with https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/KF9WB.

Code availability

The software packages used in this study are standard: VASP (version 5.4) (a commercial code package; see www.vasp.at), DeePMD-kit (https://github.com/deepmodeling/deepmd-kit), phonopy (http://phonopy.github.io/phonopy/), LAMMPS (https://www.lammps.org/), PLUMED 2 (https://www.plumed.org/doc-v2.6/user-doc/html/index.html).

References

Cooper, R. & Kohlstedt, D. in High-Pressure Research in Geophysics Vol. 12 (eds Akimoto, S. & Manghnani, M. H.) 217–228 (Springer, 1982).

Montazerian, M. & Zanotto, E. D. Nucleation, growth, and crystallization in oxide glass-formers. A current perspective. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 87, 405–429 (2022).

James, P. F. Kinetics of crystal nucleation in silicate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 73, 517–540 (1985).

Canup, R. M. Forming a Moon with an Earth-like composition via a giant impact. Science 338, 1052–1055 (2012).

Nomura, R. et al. Spin crossover and iron-rich silicate melt in the Earth’s deep mantle. Nature 473, 199–202 (2011).

Labrosse, S., Hernlund, J. W. & Coltice, N. A crystallizing dense magma ocean at the base of the Earth’s mantle. Nature 450, 866–869 (2007).

Deng, J., Miyazaki, Y., Yuan, Q. & Du, Z. Deep mantle heterogeneities formed through a basal magma ocean contaminated by core exsolution. Nat. Geosci. 18, 1056–1062 (2025).

Mukhopadhyay, S. & Parai, R. Noble gases: a record of Earth’s evolution and mantle dynamics. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 47, 389–419 (2019).

Solomatov, V. in Treatise on Geophysics 2nd edn (ed. Schubert, G.) 81–104 (Elsevier, 2015).

Solomatov, V. S. & Stevenson, D. J. Suspension in convective layers and style of differentiation of a terrestrial magma ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 98, 5375–5390 (1993).

Monteux, J., Qaddah, B. & Andrault, D. Conditions for segregation of a crystal-rich layer within a convective magma ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 128, e2023JE007805 (2023).

Patočka, V., Calzavarini, E. & Tosi, N. Settling of inertial particles in turbulent Rayleigh-Bénard convection. Phys. Rev. Fluids 5, 114304 (2020).

Boukaré, C.-E. & Ricard, Y. Modeling phase separation and phase change for magma ocean solidification dynamics. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 18, 3385–3404 (2017).

Rose, L. A. & Brenan, J. M. Wetting properties of Fe-Ni-Co-Cu-O-S melts against olivine: implications for sulfide melt mobility. Econ. Geol. 96, 145–157 (2001).

Fokin, V. M., Zanotto, E. D., Yuritsyn, N. S. & Schmelzer, J. W. P. Homogeneous crystal nucleation in silicate glasses: a 40 years perspective. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 352, 2681–2714 (2006).

Zaragoza, A. et al. Competition between ices Ih and Ic in homogeneous water freezing. J. Chem. Phys. 143, 134504 (2015).

Niu, H., Bonati, L., Piaggi, P. M. & Parrinello, M. Ab initio phase diagram and nucleation of gallium. Nat. Commun. 11, 2654 (2020).

Deng, J., Niu, H., Hu, J., Chen, M. & Stixrude, L. Melting of MgSiO3 determined by machine learning potentials. Phys. Rev. B 107, 064103 (2023).

Niu, H., Piaggi, P. M., Invernizzi, M. & Parrinello, M. Molecular dynamics simulations of liquid silica crystallization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 115, 5348–5352 (2018).

Potapov, O. V., Fokin, V. M. & Filipovich, V. N. Nucleation and crystal growth in water containing soda–lime–silica glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 247, 74–78 (1999).

Andrault, D. et al. Solidus and liquidus profiles of chondritic mantle: implication for melting of the Earth across its history. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 304, 251–259 (2011).

Fiquet, G. et al. Melting of peridotite to 140 gigapascals. Science 329, 1516–1518 (2010).

Turnbull, D. Correlation of liquid-solid interfacial energies calculated from supercooling of small droplets. J. Chem. Phys. 18, 769–769 (1950).

Fokin, V. M. & Zanotto, E. D. Crystal nucleation in silicate glasses: the temperature and size dependence of crystal/liquid surface energy. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 265, 105–112 (2000).

Laird, B. B. & Davidchack, R. L. Direct calculation of the crystal−melt interfacial free energy via molecular dynamics computer simulation. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 17802–17812 (2005).

Fokin, V. M., Zanotto, E. D. & Schmelzer, J. W. P. Homogeneous nucleation versus glass transition temperature of silicate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 321, 52–65 (2003).

Monteux, J., Andrault, D. & Samuel, H. On the cooling of a deep terrestrial magma ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 448, 140–149 (2016).

Stixrude, L., de Koker, N., Sun, N., Mookherjee, M. & Karki, B. B. Thermodynamics of silicate liquids in the deep Earth. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 278, 226–232 (2009).

Boukaré, C. E., Ricard, Y. & Fiquet, G. Thermodynamics of the MgO-FeO-SiO2 system up to 140 GPa: application to the crystallization of Earth’s magma ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 120, 6085–6101 (2015).

Nabiei, F. et al. Investigating magma ocean solidification on Earth through laser-heated diamond anvil cell experiments. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL092446 (2021).

Dowty, E. in Physics of Magmatic Processes (ed. Hargraves, R. B.) Ch. 10, 419–486 (Princeton Univ. Press, 1980).

Asahara, Y. et al. Formation of metastable cubic-perovskite in high-pressure phase transformation of Ca(Mg, Fe, Al)Si2O6. Am. Mineral. 90, 457–462 (2005).

Ito, E., Kubo, A., Katsura, T. & Walter, M. J. Melting experiments of mantle materials under lower mantle conditions with implications for magma ocean differentiation. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 143–144, 397–406 (2004).

Fei, H., Faul, U. & Katsura, T. The grain growth kinetics of bridgmanite at the topmost lower mantle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 561, 116820 (2021).

Yamazaki, D., Yoshino, T., Matsuzaki, T., Katsura, T. & Yoneda, A. Texture of (Mg,Fe)SiO3 perovskite and ferro-periclase aggregate: implications for rheology of the lower mantle. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 174, 138–144 (2009).

Panero, W. R., Pigott, J. S., Reaman, D. M., Kabbes, J. E. & Liu, Z. Dry (Mg,Fe)SiO3 perovskite in the Earth’s lower mantle. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 120, 894–908 (2015).

Ghosh, D. B. & Karki, B. B. Transport properties of carbonated silicate melt at high pressure. Sci. Adv. 3, e1701840 (2017).

Caracas, R., Hirose, K., Nomura, R. & Ballmer, M. D. Melt–crystal density crossover in a deep magma ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 516, 202–211 (2019).

Dragulet, F. & Stixrude, L. Partitioning of iron between (Mg,Fe)SiO3 liquid and bridgmanite. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL107979 (2024).

Xing, C.-M., Wang, C. Y., Charlier, B. & Namur, O. Ubiquitous dendritic olivine constructs initial crystal framework of mafic magma chamber. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 594, 117710 (2022).

Deguen, R., Alboussière, T. & Brito, D. On the existence and structure of a mush at the inner core boundary of the Earth. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 164, 36–49 (2007).

Bergman, M. I. Estimates of the Earth’s inner core grain size. Geophys. Res. Lett. 25, 1593–1596 (1998).

Tsujino, N. et al. Viscosity of bridgmanite determined by in situ stress and strain measurements in uniaxial deformation experiments. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm1821 (2022).

Garnero, E. J. & McNamara, A. K. Structure and dynamics of Earth’s lower mantle. Science 320, 626–628 (2008).

Talavera-Soza, S., Cobden, L., Faul, U. H. & Deuss, A. Global 3D model of mantle attenuation using seismic normal modes. Nature 637, 1131–1135 (2025).

Herzberg, C. & Zhang, J. Melting experiments on anhydrous peridotite KLB-1: compositions of magmas in the upper mantle and transition zone. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 101, 8271–8295 (1996).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Wang, H., Zhang, L., Han, J. & Weinan, E. DeePMD-kit: a deep learning package for many-body potential energy representation and molecular dynamics. Comput. Phys. Commun. 228, 178–184 (2018).

Zhang, S., Hu, J., Sun, X., Deng, J. & Niu, H. Structural heterogeneity of MgSiO3 liquid and its connection with dynamical properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 204101 (2025).

Piaggi, P. M. & Parrinello, M. Multithermal-multibaric molecular simulations from a variational principle. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 050601 (2019).

Barducci, A., Bussi, G. & Parrinello, M. Well-tempered metadynamics: a smoothly converging and tunable free-energy method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 020603 (2008).

Branduardi, D., Bussi, G. & Parrinello, M. Metadynamics with adaptive Gaussians. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 2247–2254 (2012).

McDonough, W. F. & Sun, S. S. The composition of the Earth. Chem. Geol. 120, 223–253 (1995).

Stixrude, L. & Lithgow-Bertelloni, C. Thermodynamics of mantle minerals – II. Phase equilibria. Geophys. J. Int. 184, 1180–1213 (2011).

Davis, M. J., Ihinger, P. D. & Lasaga, A. C. Influence of water on nucleation kinetics in silicate melt. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 219, 62–69 (1997).

Fenn, P. M. The nucleation and growth of alkali feldspars from hydrous melts. Can. Mineral. 15, 135–161 (1977).

Hammer, J. E. Crystal nucleation in hydrous rhyolite: experimental data applied to classical theory. Am. Mineral. 89, 1673–1679 (2004).

Arzilli, F. et al. Plagioclase nucleation and growth kinetics in a hydrous basaltic melt by decompression experiments. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 170, 55 (2015).

Fletcher, N. H. Size effect in heterogeneous nucleation. J. Chem. Phys. 29, 572–576 (1958).

Solomatov, V. S. Batch crystallization under continuous cooling: analytical solution for diffusion limited crystal growth. J. Cryst. Growth 148, 421–431 (1995).

Alfè, D. Melting curve of MgO from first-principles simulations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 235701 (2005).

Castro, R. H. R., Tôrres, R. B., Pereira, G. J. & Gouvêa, D. Interface energy measurement of MgO and ZnO: understanding the thermodynamic stability of nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 22, 2502–2509 (2010).

Christensen, U. R. Dynamo scaling laws and applications to the planets. Space Sci. Rev. 152, 565–590 (2010).

Bower, D. J., Sanan, P. & Wolf, A. S. Numerical solution of a non-linear conservation law applicable to the interior dynamics of partially molten planets. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 274, 49–62 (2018).

Stixrude, L., Scipioni, R. & Desjarlais, M. P. A silicate dynamo in the early Earth. Nat. Commun. 11, 935 (2020).

Ziegler, L. B. & Stegman, D. R. Implications of a long-lived basal magma ocean in generating Earth’s ancient magnetic field. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 14, 4735–4742 (2013).

Sosso, G. C. et al. Crystal nucleation in liquids: open questions and future challenges in molecular dynamics simulations. Chem. Rev. 116, 7078–7116 (2016).

Auer, S. & Frenkel, D. Prediction of absolute crystal-nucleation rate in hard-sphere colloids. Nature 409, 1020–1023 (2001).

Espinosa, J. R., Sanz, E., Valeriani, C. & Vega, C. Homogeneous ice nucleation evaluated for several water models. J. Chem. Phys. 141, 18C529 (2014).

Kurz, W., Fisher, D. J. & Trivedi, R. Progress in modelling solidification microstructures in metals and alloys: dendrites and cells from 1700 to 2000. Int. Mater. Rev. 64, 311–354 (2019).

Xu, J. et al. Silicon and magnesium diffusion in a single crystal of MgSiO3 perovskite. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 116, JB008444 (2011).

Yoshino, T., Makino, Y., Suzuki, T. & Hirata, T. Grain boundary diffusion of W in lower mantle phase with implications for isotopic heterogeneity in oceanic island basalts by core-mantle interactions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 530, 115887 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank V. Solomatov, Z. Du, J. Wang, M. Chen and H. Luo for discussions and Y. Peng for the assistance with simulations. We acknowledge the following grants: National Science Foundation (EAR-2223935 to L.S.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 92370118 to H.N.), the Research Fund of the State Key Laboratory of Solidification Processing (NPU), China (grant no. 2024-ZD-01 to H.N.) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities. The simulations presented in this article are performed on computational resources managed and supported by Princeton Research Computing, a consortium of groups including the Princeton Institute for Computational Science and Engineering (PICSciE) and the Office of Information Technology’s High Performance Computing Center and Visualization Laboratory at Princeton University. Simulations are also performed at the local cluster in H.N.’s group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D. and L.S. conceived the original idea. J.D. and H.N. conceived and coordinated the entire project. J.H., Y.S., H.N. and J.D. performed theoretical calculations and modelling. J.L. provided feedback on data interpretation and analysis. J.D. wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the discussion and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Artem Oganov, Yanick Ricard and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Structure factors and collective variables.

a, The simulated structure factors of bridgmanite (blue) and liquid (orange) using only Mg and Si atoms at 25, 50, 75, 100, 125 and 140 GPa. b, Probability distributions of the collective variables Si for the bridgmanite and liquid phases at 25, 50, 75, 100, 125 and 140 GPa. The dashed line denotes D(P), the maximum value of the Gaussian distribution of Si in the liquid phase under the respective pressures.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Critical cluster size of nucleus NC estimated from molecular dynamics simulations.

All molecular dynamics simulations start with an identical initial configuration. The solid curves depict the fluctuation of nucleus sizes over time at 5,075 K (red), 5,100 K (blue) and 5,125 K (grey) at 125 GPa. The horizontal dashed line represents the estimated NC value, with the error bar indicated by the light blue bar. 5,075 K and 5,125 K are below and above the critical temperature that corresponds to this initial nucleus and thus the nucleus grows and dissolves, respectively. 5,100 K, on the other hand, is very close to the critical temperature and therefore has a nearly equal chance of dissolution and growth. As such, one simulation ends with nucleus growth and the other ends with dissolution.

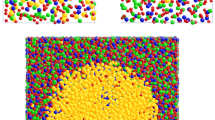

Extended Data Fig. 3 A snapshot with the nucleus crystallized from the melt.

Simulation is at 100 GPa with a system comprising 1,023,120 atoms. Only Mg and Si atoms are shown, represented by red and blue colours, respectively. Liquid-like atoms are shown with a transparent colour. In the right panel, the regions enclosed by the green surface serve to highlight the spherical-like nucleus that crystallized from the melt.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Growth and melting process of MgSiO3 bridgmanite.

a–d, Simulations are at 100 GPa with varying system sizes. The simulation cells comprise of 16,000 atoms with a box length of about 5 nm (a), 140,800 atoms with a box length of about 10 nm (b), 491,520 atoms with a box length of about 15 nm (c) and 1,023,120 atoms with a box length of about 20 nm (d), respectively. The middle panel illustrates the initial configurations of the four systems, with a crystal nucleus corresponding to a size of approximately 3.5 nm serving as a seed. The left and right panels exhibit the melting and growth of the crystal at the respective marked temperatures. Only Mg atoms and Si atoms are shown in the snapshots and they are coloured with the value of D(P), in the same way as shown in Fig. 1b.

Extended Data Fig. 5 System size convergence of interfacial energy.

The interfacial free energy plotted against system size (that is, the number of atoms in the simulation cell). The simulation cells consist of 7,680, 11,340, 16,000, 140,800, 491,520 and 1,023,120 atoms, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Thermophysical properties and diffusivity of the MgSiO3 system.

a, Chemical potential difference between the liquid and the crystalline MgSiO3 (Δμ) at 125 GPa calculated by the empirical formula (orange) \(\Delta \mu =\Delta {H}_{{\rm{m}}}\left(1-\frac{T}{{T}_{{\rm{m}}}}\right)\) and thermodynamic integration (blue), respectively. b, Pressure–volume results of MgSiO3 bridgmanite at 1,000 K (cyan), 2,000 K (blue), 3,000 K (green), 4,000 K (red), 5,000 K (magenta) and 6,000 K (yellow). The fitted curves are calculated with the best-fitting equation of state parameters. The calculated pressure–temperature–volume (P–V–T) results are curve-fit to the following equation P(V, T) = P(V, T0) + BTH(T − T0), in which P(V, T0) represents the reference isotherm corresponding to T0 = 2,000 K, using a fourth-order Birch–Murnaghan equation of state and a volume-dependent \({B}_{{\rm{TH}}}(V)=\left[a-b\left(\frac{V}{{V}_{0}}\right)+c{\left(\frac{V}{{V}_{0}}\right)}^{2}\right]/1,\,000\), in which a, b and c are constants, V0 = 24.24 cm3 mol−1 and the corresponding reference pressure P0 at 2,000 K is 20 GPa. The best-fitting parameters are K0 = 258.00 ± 1.53 GPa, K′ = 4.22 ± 0.11, K″ = −0.021 ± 0.003 GPa−1, a = 16.22 ± 3.18, b = 20.75 ± 7.24 and c = 1.66 ± 4.18. c, Enthalpy of melting of MgSiO3 bridgmanite (black dots) along with the best-fitting curve, that is, \(\Delta {H}_{{\rm{m}}}\,({\rm{k}}{\rm{J}}\,{{\rm{m}}{\rm{o}}{\rm{l}}}^{-1})=-0.0115{P}^{2}+3.287P+108.118\), in which P is pressure in GPa. d, Diffusivity of Si along the peridotitic (dashed)22 and chondritic (solid)21,46 liquidi, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Effects of iron on interfacial energy.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Heterogeneous nucleation with the embryo of bridgmanite nucleating on periclase in parent-phase silicate liquid.

a, Schematic of heterogeneous nucleation configuration. b, Contact angle as a function of pressure along the peridotitic (dashed line)22 and chondritic (solid line)21 liquidi. c, The ratio of apparent interfacial energy to homogeneous nucleation interfacial energy for various contact angles and x is the ratio of the periclase crystal size R and critical nucleation size (r*), x = R/r*. The red-shaded region indicates plausible values of contact angles from b.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Diffusivity of Si in MgSiO3 liquid.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Nucleation rate of bridgmanite at 115 (blue), 125 (green) and 140 GPa (red) as a function of the temperature.

The symbols are the calculated results and the solid lines are the corresponding best fits. The dashed lines are adiabats of a cooling magma ocean of a chondritic bulk composition take from ref. 27. Overall, the nucleation rate at 140 GPa is around eight orders of magnitude higher than that at 115 GPa any time along the adiabat. Predicted grain sizes are sensitive to the assumed cooling rate. Values shown are illustrative for the chosen parameter sets and should not be interpreted as quantitative predictions.

Extended Data Fig. 11 Deformation mechanism maps of bridgmanite at 25 GPa/1,900 K (a,c) and 25 GPa/2,500 K (b,d) respectively.

The coloured contours represent the strain rate (s−1) and viscosity (Pa s) in (a, b) and (c, d), respectively. Solid lines distinguish regimes with dominant deformation mechanisms of dislocation creep and diffusion creep. The green (magenta) vertical bars represent the grain size of the shallow lower mantle in the WMO (lowermost mantle in the BMO) and the likely stresses of the mantle convection cores. Parameters used to construct these figures are tabulated in Extended Data Table 1.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Deng, J., Hu, J., Shi, Y. et al. The potential for bridgmanite megacrysts to drive magma ocean segregation. Nature (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-10063-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-10063-5