Abstract

Sweet corn is an important vegetable crop consumed globally. However, the genetic differentiation between field corn and sweet corn, and the impact of breeding on the metabolite composition and flavor (other than sweetness) of sweet corn, remain poorly understood. Here we assembled a cultivated sweet-corn genome de novo and re-sequenced 295 diverse sweet-corn inbred lines. We examined the genetic architecture of sweet-corn kernel quality by combining genetic, metabolite and expression profiling methodologies. New genes (for example, ZmAPS1, ZmSK1 and ZmCRR5) and metabolites associated with flavor and consumer preference were identified, highlighting important target flavor metabolites, including sugars, acids and volatiles. These findings provide valuable knowledge and targets for future genetic breeding of sweet-corn flavor, and to balance grain yield and quality and contribute to our broader understanding of crop diversification.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All datasets supporting the findings of this study have been deposited into the CNGB Sequence Archive of the China National GeneBank DataBase (https://db.cngb.org/) under the following accession nos.: de novo assembled genomes and raw data at CNP0004684, CNP0003283 and CNP0003295; raw WGS data for the 295 sweet-corn accessions at CNP0003213; RNA-seq data for the 280 sweet-corn accessions at CNP0003294; and RNA-seq for knockout and wild-type lines at CNP0003291 and CNP0004707. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

No customized code was generated for this study. All analyses were performed using publicly available software with parameters detailed in Methods.

References

Quick Stats (United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), 2022); https://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/results/1AB625B8-19CC-312D-ACF6-58D2EA98E806?pivot=short_desc

Singh, I., Langyan, S. & Yadava, P. Sweet corn and corn-based sweeteners. Sugar Tech 16, 144–149 (2014).

Tracy, W. F., Shuler, S. L. & Dodson-Swenson, H. The use of endosperm genes for sweet corn improvement: a review of developments in endosperm genes in sweet corn since the seminal publication in Plant Breeding Reviews, Volume 1, by Charles Boyer and Jack Shannon (1984). Plant Breed. Rev. 43, 215–241 (2019).

Tracy, W. F., Whitt, S. R. & Buckler, E. S. Recurrent mutation and genome evolution: example of Sugary1 and the origin of sweet maize. Crop Sci. 46, S49–S54 (2006).

Hu, Y. et al. Genome assembly and population genomic analysis provide insights into the evolution of modern sweet corn. Nat. Commun. 12, 1227 (2021).

De Vries, B. D. & Tracy, W. F. Characterization of endosperm carbohydrates in isa2-339 maize and interactions with su1-ref. Crop Sci. 56, 2277–2286 (2016).

Dodson-Swenson, H. G. & Tracy, W. F. Endosperm carbohydrate composition and kernel characteristics of shrunken2-intermediate (sh2-i/sh2-i Su1/Su1) and shrunken2-intermediate-sugary1-reference (sh2-i/sh2-i su1-r/su1-r) in sweet corn. Crop Sci. 55, 2647–2656 (2015).

Da Fonseca, R. R. et al. The origin and evolution of maize in the Southwestern United States. Nat. Plants 1, 14003 (2015).

Allam, M. et al. Identification of QTLs involved in cold tolerance in sweet x field corn. Euphytica 208, 353–365 (2016).

Song, J. F. et al. Carotenoid composition and changes in sweet and field corn (Zea mays) during kernel development. Cereal Chem. 93, 409–413 (2016).

Szymanek, M., Tanas, W. & Kassar, F. H. Kernel carbohydrates concentration in sugary-1, sugary enhanced and shrunken sweet corn kernels. Agric. Agric. Sci. Proc. 7, 260–264 (2015).

Hufford, M. B. et al. Comparative population genomics of maize domestication and improvement. Nat. Genet. 44, 808–811 (2012).

Zhang, X. et al. Maize sugary enhancer1 (se1) is a gene affecting endosperm starch metabolism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 20776–20785 (2019).

Baseggio, M. et al. Genome-wide association and genomic prediction models of tocochromanols in fresh sweet corn kernels. Plant Genome 12, 180038 (2019).

Li, K. et al. Large-scale metabolite quantitative trait locus analysis provides new insights for high-quality maize improvement. Plant J. 99, 216–230 (2019).

Chen, W. K. et al. Convergent selection of a WD40 protein that enhances grain yield in maize and rice. Science 375, eabg7985 (2022).

Hufford, M. B. et al. De novo assembly, annotation, and comparative analysis of 26 diverse maize genomes. Science 373, 655–662 (2021).

Yang, N. et al. Genome assembly of a tropical maize inbred line provides insights into structural variation and crop improvement. Nat. Genet. 51, 1052–1059 (2019).

Fu, J. et al. RNA sequencing reveals the complex regulatory network in the maize kernel. Nat. Commun. 4, 2832 (2013).

Wen, W. et al. Metabolome-based genome-wide association study of maize kernel leads to novel biochemical insights. Nat. Commun. 5, 3438 (2014).

Yang, X. H. et al. Characterization of a global germplasm collection and its potential utilization for analysis of complex quantitative traits in maize. Mol. Breed. 28, 511–526 (2011).

Liu, H. et al. Distant eQTLs and non-coding sequences play critical roles in regulating gene expression and quantitative trait variation in maize. Mol. Plant 10, 414–426 (2017).

Chen, L. et al. Genome sequencing reveals evidence of adaptive variation in the genus Zea. Nat. Genet. 54, 1736–1745 (2022).

Trimble, L., Shuler, S. & Tracy, W. F. Characterization of five naturally occurring alleles at the sugary1 locus for seed composition, seedling emergence, and isoamylase1 activity. Crop Sci. 56, 1927–1939 (2016).

Yang, J. et al. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88, 76–82 (2011).

Yang, R. et al. Widely targeted metabolomics analysis reveals key quality-related metabolites in kernels of sweet corn. Int. J. Genom. 1, 2654546 (2021).

Li, P. et al. Fructose sensitivity is suppressed in Arabidopsis by the transcription factor ANAC089 lacking the membrane-bound domain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 3436–3441 (2011).

Liu, H. et al. Genomic, transcriptomic, and phenomic variation reveals the complex adaptation of modern maize breeding. Mol. Plant 8, 871–884 (2015).

Zhang, X. et al. The tin1 gene retains the function of promoting tillering in maize. Nat. Commun. 10, 5608 (2019).

Zhu, G. et al. Rewiring of the fruit metabolome in tomato breeding. Cell 172, 249–261.e12 (2018).

Colantonio, V. et al. Metabolomic selection for enhanced fruit flavor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2115865119 (2022).

Fernie, A. R. & Alseekh, S. Metabolomic selection-based machine learning improves fruit taste prediction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2201078119 (2022).

Vaser, R. et al. Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome Res. 27, 737–746 (2017).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS ONE 9, e112963 (2014).

Chen, S. et al. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 3, 95–98 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95 (2017).

Simão, F. A. et al. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015).

Jurka, J. et al. Repbase update: a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 110, 462–467 (2005).

Edgar, R. C. & Myers, E. W. PILER: identification and classification of genomic repeats. Bioinformatics 21, i152–i158 (2005).

Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 573–580 (1999).

Rhie, A. et al. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 21, 245 (2020).

Ou, S. et al. Benchmarking transposable element annotation methods for creation of a streamlined, comprehensive pipeline. Genome Biol. 20, 275 (2019).

Ou, S. & Ning, J. LTR_retriever: a highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 176, 1410–1422 (2018).

Ou, S. et al. Assessing genome assembly quality using the LTR Assembly Index (LAI). Nucleic Acids Res. 46, e126 (2018).

Zhang, G. et al. Genome sequence of foxtail millet (Setaria italica) provides insights into grass evolution and biofuel potential. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 549–554 (2012).

Yu, J. et al. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica). Science 296, 79–92 (2002).

International Brachypodium Initiative. Genome sequencing and analysis of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon. Nature 463, 763–768 (2010).

Paterson, A. et al. The Sorghum bicolor genome and the diversification of grasses. Nature 457, 551–556 (2009).

Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408, 796–815 (2000).

Jiao, Y. et al. Improved maize reference genome with single-molecule technologies. Nature 546, 524–527 (2017).

Sun, S. et al. Extensive intraspecific gene order and gene structural variations between Mo17 and other maize genomes. Nat. Genet. 50, 1289–1295 (2018).

Holt, C. & Yandell, M. MAKER2: an annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC Bioinform. 12, 491 (2011).

Ranallo-Benavidez, T. R., Jaron, K. S. & Schatz, M. C. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat. Commun. 11, 1432 (2020).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770 (2011).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

DePristo, M. A. et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 43, 491–498 (2011).

Quinlan, A. R. & Hall, I. M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 (2010).

Alexander, D. H., Novembre, J. & Lange, K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 19, 1655–1664 (2009).

Danecek, P. et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 27, 2156–2158 (2011).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007).

Paradis, E. pegas: an R package for population genetics with an integrated–modular approach. Bioinformatics 26, 419–420 (2010).

Zhang, C. et al. PopLDdecay: a fast and effective tool for linkage disequilibrium decay analysis based on variant call format files. Bioinformatics 35, 1786–1788 (2019).

Chen, H., Patterson, N. & Reich, D. Population differentiation as a test for selective sweeps. Genome Res. 20, 393–402 (2010).

Szpiech, Z. A. selscan 2.0: scanning for sweeps in unphased data. Bioinformatics 40, btae006 (2024).

Salem, M. A. et al. Protocol: a fast, comprehensive and reproducible one-step extraction method for the rapid preparation of polar and semi-polar metabolites, lipids, proteins, starch and cell wall polymers from a single sample. Plant Methods 12, 45 (2016).

Wang, H. et al. A subsidiary cell-localized glucose transporter promotes stomatal conductance and photosynthesis. Plant Cell 31, 1328–1343 (2019).

Yan, S. et al. Comparative metabolomic analysis of seed metabolites associated with seed storability in rice (Oryza sativa L.) during natural aging. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 127, 590–598 (2018).

Alseekh, S. et al. Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics: a guide for annotation, quantification and best reporting practices. Nat. Methods 18, 747–756 (2021).

Bradbury, P. J. et al. TASSEL: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics 23, 2633–2635 (2007).

Li, M. X. et al. Evaluating the effective numbers of independent tests and significant p-value thresholds in commercial genotyping arrays and public imputation reference datasets. Hum. Genet. 131, 747–756 (2012).

Lander, E. & Kruglyak, L. Genetic dissection of complex traits: guidelines for interpreting and reporting linkage results. Nat. Genet. 11, 241–247 (1995).

Giambartolomei, C. et al. Bayesian test for colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using summary statistics. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004383 (2014).

Pertea, M. et al. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protoc. 11, 1650–1667 (2016).

Liu, H. et al. CRISPR-P 2.0: an improved CRISPR-Cas9 tool for genome editing in plants. Mol. Plant 10, 530–532 (2017).

Liu, H. J. et al. High-throughput CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis streamlines trait gene identification in maize. Plant Cell 32, 1397–1413 (2020).

Bates, D. et al. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Sun, G. et al. Variation explained in mixed-model association mapping. Heredity 105, 333–340 (2010).

Wu, T. et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: a universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2, 100141 (2021).

Hartigan, J. & Wong, M. A K-means clustering algorithm. J. R. Stat. Soc. C 28, 100–108 (1979).

Efron, B., Hastie, T., Johnstone, I. & Tibshirani, R. Least angle regression. Ann. Stat. 32, 407–499 (2004).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 32321005 to J.Y., U1901201 to J.Y. and 32001563 to K.L.), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2022YFD1201502 to G.L.), the Earmarked Fund for CARS (grant no. CARS-02-85 to G.L.), the Guangdong S&T Program (grant no. 2022B0202060003 to Y.Y.), the Science and Technology Major Program of Hubei Province (grant no. 2021ABA011 to J.Y.), the Agricultural Competitive Industry Discipline Team Building Project of Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (grant no. 202115TD to G.L.), the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (grant no. 202102021015 to K.L.), the Project of Collaborative Innovation Center of Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (grant no. XTXM202203 to S.Y.), the Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Plan Project (grant no. 2023B1212060038 to G.L.) and the Special Fund for Scientific Innovation Strategy-construction of High-Level Academy of Agriculture Science (grant nos. R2019YJ-YB1002 to K.L. and R2020PY-JX019 to S.Y.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. We are grateful to Maize Research Institute of Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences for help in collecting sweet corn resources. Computation resources were provided by the high-throughput computing platform of the National Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Improvement at Huazhong Agricultural University and supported by Hao Liu.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y. and J.H. conceived and designed the research. Y.Y., W.Q.L., G.L., W.L., Y.N.X., N.Z., L.Z. and K.L. managed the project. K.L., Y.Y., Q.Z., J.Y.L., L.C., Y.J.X., N.Y., H.-J.L., L.F. and S.G. performed the genome sequencing and bioinformatics. Y.Y., J.H.L., L.X., X.Q., C.L., W.J.L., Y.L. and Y.X. prepared the samples for resequencing and transcriptome profile of the sweet-corn population and contributed to data analysis. W.Q.L. was responsible for the filed corn planting and data collection. S.Y., W.H. and Q.K. performed metabolome analyses using GC–MS and LC–MS platforms. J.X., K.L., W.Z. and T.W. managed the knockout lines and performed the molecular experiments. K.L., H.-J.L., S.Y., A.R.F., J.H. and J.Y. wrote and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.X. is an employee of WIMI Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Genetics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Genetic differences of sweet and field corn.

a, Length of specific sequences in the RC genome compared to B73. b, Distribution of specific sequences in the RC genome compared to B73. c, Length of specific sequences in the RC genome compared to Ia453. d, Distribution of specific sequences in the RC genome compared to Ia453. e, Length of specific sequences in the RC genome compared to IL14H. f, Distribution of specific sequences in the RC genome compared to IL14H. g, Length of specific sequences in the RC genome compared to p39. h, Distribution of specific sequences in the RC genome compared to p39. i, Population structure of sweet and field corn populations, inferred using the maximum-likelihood method with three and four ancestral components (K = 3, 4).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Genetic variation in sh2 and su1.

a, Synteny map highlighting an inversion in sh2 in RC genome compared to the field corn genome TX303 and parviglumis genome TIL11. b, Haplotype network analysis of 264 SNPs in the sh2-RC region, based on the RC gene model that includes the identified inversion. (c) LD plot (r2 values) for sh2 and flanking regions ( < 500 kb) in sweet corn population, and in kernel corn from (d) TEM population and (e) TST population. Nucleotide diversity (π) around (f) sh2 and (g) su1 in both sweet and field corn populations. h, Haplotype network analysis of SNPs in the su1 region. i, Structural analysis identifying 5 alleles in the Su1 gene within sweet corn population. j, Comparison of relative sugar content (sum of sucrose, maltose, glucose, and fructose) among different su1 alleles. k, Comparison of relative pericarp thickness in immature kernels across different alleles of su1. The values to the left of each bar represent the number of sweet corn lines analyzed in (j) and (k). Data points show individual measurements; bar heights represent mean values and error bars represent the mean values ± s.d. Differences between groups were assessed using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. l, Principal component analysis of 63 SNPs discovered in su1 region.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Knockout of Sh2 and Su1 by CRISPR-Cas9.

Two sgRNAs designed for gene editing on Sh2 (a) and Su1(b), respectively, shown in red. Mutations and deletions are indicated. c, Phenotypes of maize ears from su1 and sh2 CRISPR-knockout line. Scale bars, 1 cm. d, Metabolites identified with significant changes and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in Sh2 and Su1 mutants compared to wild types. e, DEGs between sh2 and WT in kernel tissues at 20 DAP. f, Metabolomic comparison of sh2 and WT in kernel tissues at 20 DAP; fold change calculated using mean values (WT, n = 12; Mutant, n = 12). g, DEGs between su1 and WT in kernel tissues at 20 DAP. h, Comparison of metabolome of su1 and WT in kernel tissues at 20 DAP (WT, n = 12; Mutant, n = 12). i, Pericarp thickness comparisons between Su1 and Sh2 CRISPR-knockout lines and wild type kernels. Box plots are defined by the median (centre line), the 5th and 95th percentiles (box limits), and the whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values. Individual data points are overlaid. P values (i) were calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

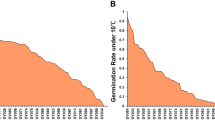

Extended Data Fig. 4 Distribution of eGWAS signals in sweet and field corn populations.

Scatter plots show the genomic positions of genes and corresponding eQTL signals in sweet (a) and field (b) corn populations (upper panels). Distribution of eGWAS signal counts per 500 kb window across the genome in sweet (a) and field (b) corn populations (lower panels). The horizontal dashed line indicates the threshold for signal hotspots (permutation test P < 0.05).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Mapping results for flavor ratings and metabolites.

a, Distribution of mQTL and flavor rating-related QTL across the maize genome. The arrow shows loci where mQTL and flavor rating-related QTL are colocalized. b, Flowchart illustrating the rationale and statistical framework used in the present study. c, Correlation analysis of sweet corn flavor ratings between two biological replicates in 2019. d, Correlation analysis of sweet corn flavor ratings between experiments conducted in 2017 and 2019.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Functional analysis of su1 alleles.

Significant differences between Su1-RC and Su1-B73 alleles across the sweet corn population in sucrose (a), maltose (b), glucose (c), and fructose (d), respectively. e, Significant differences in expression levels among four su1 alleles. f, Significant differences in flavor values among four alleles of su1. g, Correlation analysis between pericarp thickness from taste rating experiments and su1 expression levels. h, Sweetness from taste rating experiments, showing no difference between Su1-B73 and Su1-RC types. Differences between groups were assessed using a two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Functional identification of candidate genes.

a, Gene model of ZmAPS1. CRISPR-Cas9 generated mutants in ZmAPS1 are shown, with sgRNAs in red and deletions shown as dashes. Violin plots showing differences of adenosine (b) and methyl-phosphate (c) content between genotypes at the InDel 3 (-/AAC). Knockout of Zm0001eb405310 (d) and Zm0001eb214960 (e) by CRISPR-Cas9. Violin plots of relative erythrose (f) and DL-2aminooctanoic acid (g) content between wild-type and knockout lines. Group comparisons were performed using two-tailed unpaired t-tests.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Functional identification of ZmSK1.

a, Correlation analysis between ZmSK1 expression and quinic acid content. b, Correlation analysis between quinic acid content and hundred-kernel weight. c, Correlation analysis between pericarp thickness and hundred-kernel weight. d, Knockout of ZmSK1 by CRISPR-Cas9. Mutants of ZmSK1 are shown. e, Violin plots of hundred-kernel weight between wild type and ZmSK1 knockout lines in 2022. Differences between groups were assessed using a two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Functional identification of ZmCRR5.

a, Knockout of ZmCRR5 by CRISPR-Cas9. Representative images of maize roots (b) and statistical comparison of root numbers (c) between wild type and KO-ZmCRR5 lines. d, Correlation between root numbers at seedling stage and normalized fructofuranose content. e, Hormones levels in immature kernel of ZmCRR5 knockouts and wild types. P-values were analyzed using two-tailed unpaired t-test (n = 12/12). f, Inferred phylogenetic analysis of six CRR genes across maize genome. g, Expression of six CRR genes in short apical meristem tissues of ZmCRR5 knockout and wild types. h, Expression of six CRR genes in immature kernel (20 DAP) of ZmCRR5 knockouts and wild types. Data points (g and h) show individual measurements; bar heights represent mean values and error bars represent the mean values ± s.d. Differences between groups were assessed using two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Haplotype analysis of ZmCRR5.

a, Identification of haplotype-specific (minimum allele frequency < 15% in one haplotype and corresponding allele frequency > 85% in other two haplotype groups) SNPs in ZmCRR5, shown as vertical lines in gray (introns), red (coding regions), and black (untranslated regions). were presented with gray, red and black vertical lines located in introns, coding regions and untranslated regions, respectively (upper). Below, details of 16 SNPs in coding regions, with allele frequencies for each haplotype group. Haplotype-specific SNPs are highlighted in bold. Violin plots displaying hundred-kernel weight (b) and pericarp thickness (c) across the three haplotype groups. P-values were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

Supplementary information

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, K., Yu, Y., Yan, S. et al. Genetic basis of flavor complexity in sweet corn. Nat Genet 57, 2842–2851 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-025-02401-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-025-02401-0