Abstract

The host genetics of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have previously been studied based on cases from the earlier waves of the pandemic in 2020 and 2021, identifying 51 genomic loci associated with infection and/or severity. SARS-CoV-2 has shown rapid sequence evolution, increasing transmissibility, particularly for Omicron variants, which raises the question of whether this affected the host genetic factors. We performed a genome-wide association study of SARS-CoV-2 infection with Omicron variants, including more than 150,000 cases from four cohorts. We identified 13 genome-wide significant loci, of which only five were previously described as associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. The strongest signal was a single nucleotide polymorphism in an intron of ST6GAL1, a gene affecting immune development and function, connected to three other associated loci (harboring MUC1, MUC5AC and MUC16) through O-glycan biosynthesis. Our study provides robust evidence for individual genetic variation related to glycosylation, translating into susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infections with Omicron variants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

According to data from the World Health Organization, SARS-CoV-2 has by now caused more than 770 million cases of COVID-19, resulting in more than seven million deaths1. The largest genetic study on susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection was a genome-wide association study (GWAS) by the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative (HGI), meta-analyzing up to 219,692 cases and over three million controls, which identified 51 genetic loci2 associated with infection and/or two other outcomes related to COVID-19 disease severity. However, that study was built on a data freeze from December 2021, just after the detection of Omicron in November 2021, and therefore only included infections with earlier (pre-Omicron) SARS-CoV-2 variants. The evolution of the virus gave rise to multiple mutations that affected, among others, the transmissibility of the virus3. Omicron variants showed more mutations than earlier variants and, within a few months, infected far more individuals worldwide than all the earlier variants combined.

Given these substantial changes observed in the virus, we decided to investigate the corresponding host genetics by performing a GWAS of SARS-CoV-2 infection with Omicron variants in >150,000 cases and >500,000 controls without known SARS-CoV-2 infection by combining data from four cohorts in a meta-analysis.

Results

GWAS of Omicron infection versus no infection

In our main analysis, we compared SARS-CoV-2 infection with Omicron variants (proxied by the first reported infection observed in a period during which Omicron variants were dominating in the study cohorts, which was after the start of 2022) versus controls with no known SARS-CoV-2 infection, using data from electronic health records, viral testing or questionnaire data in the covered time period (see Methods for further details). To simplify matters, genetic variants are denoted as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) throughout the paper, so that the term ‘variant’ always refers to variation in SARS-CoV-2.

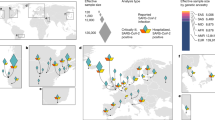

We performed a meta-analysis of four GWAS with a total of 151,825 cases and 556,568 controls (see Fig. 1 for Manhattan plot) and identified 13 genome-wide significant loci, of which eight represent novel associations for SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table 1). Four of the corresponding lead SNPs had proxies among the previously reported SNPs associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection related to earlier variants (r2 > 0.6), and for the SLC6A20 locus, the lead SNP reported for the earlier variants was in the 95% credible set of our GWAS signal (rs73062389, P = 8.9 × 10−33 in our study; see Supplementary Fig. 1). Two of these loci had been assigned to the pathway ‘entry defense in airway mucus’ (nearby genes MUC1 and MUC16) and one to ‘viral entry and innate immunity’ (SLC6A20)2. The other two loci previously reported in the context of earlier variants identified in our meta-analysis were represented by rs13100262 (RPL24) and rs492602 (FUT2). The protective allele rs492602-G is related to non-secretor status, which confers resistance to childhood ear infection and certain specific viral infections (for example, norovirus, rotavirus), as well as susceptibility to other conditions (for example, mumps, measles, kidney disease)4,5.

Meta-analysis of four GWAS with a total of 151,825 cases and 556,568 controls under an inverse-variance-weighted fixed-effects model. The y axis shows −log10(P values) (two-sided, no adjustment for multiple testing) for SNPs with P < 0.01 over the chromosomes listed on the x axis. The red line indicates the threshold for genome-wide significance (P = 5 × 10−8), and genome-wide significant loci are annotated with nearby genes.

The most significant finding was the intronic SNP rs13322149 (odds ratio (OR) for minor allele T: 0.857, P = 5 × 10−108) in ST6GAL1 (ST6 beta-galactoside alpha-2,6-sialyltransferase 1), a gene affecting immune development and function6. The encoded protein adds terminal α2,6-sialic acids to galactose-containing N-linked glycans. A recent multi-ancestry GWAS of influenza infection also identified a protective effect for the minor allele T7. The strong association with influenza was further seen in phenome-wide association results from the most recent FinnGen cohort (FinnGen release 12 (https://www.finngen.fi/en), with an OR of 0.889 for rs13322149-T (P = 5.2 × 10−10, 11,558 cases vs 415,538 controls, r2 = 0.965 between rs13322149 and the FinnGen influenza lead SNP, rs55958900). The second new locus was represented by rs708686 (OR for allele T: 1.055, P = 1.1 × 10−27), located intergenic between the fucosyltransferases FUT6 and FUT3 (Lewis gene) and from the same gene family as FUT2, harboring rs492602 mentioned above. In FinnGen release 12, the risk allele for Omicron infection rs708686-T was reported as lead SNP in cholelithiasis (OR = 1.103, P = 9.6 × 10−41, 49,834 cases vs 437,418 controls), as well as in viral and other specified intestinal infections (OR = 0.913, P = 4.4 × 10−10, 11,050 cases vs 444,292 controls), and it was the strongest protein quantitative trait locus (QTL) for FUT3 levels (β = −0.657, P = 3 × 10−126) in a proteomics study8. The third SNP, rs10787225 (OR for C: 0.966, P = 5.3 × 10−12), is located about 3 kb upstream of MXI1 (MAX interactor 1), a region with GWAS findings for, among others, blood pressure9 and blood cell phenotypes10, but the previously identified SNPs are not in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with our lead SNP. Additional novel associations include rs4447600 (OR for T: 0.971, P = 6.3 × 10−9) on 2q37.3, which is in moderate LD with rs6437219 (r2 = 0.64 in the Danish study population), associated with forced vital capacity11. Reduced forced vital capacity can indicate reduced lung function, and at this locus, the allele linked to reduced forced vital capacity is in phase with the allele conferring an increased risk of Omicron infection. The genetic association at the ABO locus changed drastically, as the previously reported SNP rs505922 linked to a protective effect of blood group O for earlier variants2 has changed direction of effect and no longer showed the strongest association (OR for major allele T: 1.022, P = 4.8 × 10−6). Instead, rs8176741 (OR for minor allele A: 0.942, P = 3.8 × 10−19, r2 = 0.159 with rs505922 in individuals of European ancestry) was the lead SNP, and as it tags blood group B, a protective effect of blood group B against SARS-CoV-2 infection with Omicron variants can be inferred.

The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) region and the MUC5AC locus have previously shown association with COVID-19 severity2, but with SNPs that show no strong LD to the lead SNP in this GWAS (r2 < 0.3). Our top HLA SNP, rs34959151 (OR for TAC: 1.042, P = 4.5 × 10−13), is in strong LD with rs1736924 (r2 = 0.989 in the Danish study population), which tags HLA-F*01:03 (ref. 12), and there is growing evidence that HLA-F has an important role in immune modulation and viral infection13.

Our finding near MUC5AC (rs28415845, OR for C: 0.97, P = 1.8 × 10−9) adds further evidence for the role of mucins in protecting against infection with Omicron variants14. Finally, rs1218577 (OR for C: 0.974, P = 3 × 10−8) is located near KCNN3, not far from the MUC1 locus. However, the SNP is located more than 300 kb away from rs6676150 in a different LD block (D′ = 0.162, r2 = 0.0096) and deserves further attention. Four lead SNPs showed signs of heterogeneity of effect between the study cohorts, with P < 0.05 in Cochran’s Q-test and I2 > 60. However, all four SNPs have P values well below the genome-wide significance threshold, and the heterogeneity is mainly a result of substantially stronger effect estimates in the Danish cohort (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for forest plots of these four SNPs and Supplementary Table 1 for results of the 13 lead SNPs in all four cohorts). This is probably a consequence of Denmark being one of the countries that had extremely high test activity with easily accessible testing for the whole population15; all cases in the cohort were identified by a positive PCR test, and controls were selected based on a negative PCR test and a test history without any positive test.

Relation to GWAS of earlier SARS-CoV-2 variants

We looked up all 51 SNPs reported by the HGI (in their Supplementary Table 5)2 as associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection and/or hospitalization (Supplementary Table 2). Apart from the five HGI loci reaching genome-wide significance (Table 1), we observed a comparable effect for rs190509934 close to ACE2, with P = 8.9 × 10−7 in the FinnGen cohort, indicating that this relatively rare SNP did not reach genome-wide significance in our study owing to reduced power resulting from being reported in only one cohort. Among the 35 HGI loci with an assigned impact of disease severity (hospitalization), only the one in the HLA region reached genome-wide significance in our GWAS (Supplementary Table 2), but SNP rs2517723 is not in strong LD with our top SNP in the region (r2 < 0.3). This finding is in line with the fact that none of the severity SNPs reached genome-wide significance in the HGI GWAS of infection, even though most of the 49,033 hospitalized cases were also among the 219,692 analyzed cases with infection.

To overcome the problems inherent in comparing two GWAS meta-analyses on different phenotypes and with different cohorts, we investigated differences between the genetic findings for earlier and Omicron variants by performing a second GWAS in our cohorts. Again, we used cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection with Omicron variants, but now versus controls with a SARS-CoV-2 infection before Omicron variants had notable case numbers (‘earlier variants’; that is, infection before December 2021, n = 87,212). The results we obtained for the lead SNPs from Table 1 (Supplementary Table 3) underlined the emergence of the ST6GAL1 locus (P = 2 × 10−49) and the new lead SNP at the ABO locus (P = 1.6 × 10−18). The difference for the previously reported ABO SNP rs505922 was even larger (P = 1.7 × 10−30), confirming the protective effect observed in earlier variants. For the other lead SNPs, P values ranged from 9.4 × 10−7 to 0.82, with the most significant difference caused by a stronger effect related to Omicron variants at the previously reported MUC16 locus.

Relation to GWAS of breakthrough infections

A recent GWAS of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections in the UK Biobank identified ten loci16, of which eight overlap with our findings (Supplementary Table 4), including all five loci that were also in common with the GWAS of infection with earlier SARS-CoV-2 variants. Among the remaining five loci associated with Omicron infection in our study, lead SNPs at four loci had P < 0.001 in the GWAS of breakthrough infections; only for the secondary signal at the chromosome 1 locus, there was no sign of association. The lead SNPs at the two remaining loci in the GWAS of breakthrough infections had attenuated effect sizes and only reached nominal significance in our meta-analysis. The UK Biobank study did not specify the time period in which the breakthrough infections occurred; however, given the overall large fraction of Omicron infections among all SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections, it can be expected that Omicron accounted for the majority of cases. For Denmark, vaccination data were available, and we compared within the Omicron cases 20,754 individuals with a completed initial round of vaccination versus 1,167 without any vaccination. We observed no significant differences at the adjusted P value of 0.038 (0.05 / 13) for any of the 13 SNPs in Table 1, and the direction of effect did not consistently agree or disagree with the results in the main GWAS of Omicron cases versus controls (Supplementary Table 5).

Relation to GWAS of influenza

We looked up our genome-wide significant loci in a recent GWAS of influenza (Supplementary Table 6), a study that also reported rs13322149 near ST6GAL1 as the lead SNP with a similar effect (OR for T: 0.888, P = 3.6 × 10−19)7.

In a total of 14 comparisons (including the only other lead SNP, rs2837113, from the influenza GWAS), we observed two more of our loci reaching the adjusted significance level of 4.2 × 10−3 for influenza: rs6676150 (OR for C: 1.038, P = 1.1 × 10−6) and the proxy SNP rs73005873 (OR for C: 1.033, P = 5.0 × 10−5) near MUC1 and MUC16, respectively, with consistent directions of effects between the studies. By contrast, the second lead SNP identified in the influenza GWAS (rs2837113, B3GALT5 locus, OR for A: 0.915, P = 4.1 × 10−32) went in the opposite direction for Omicron (OR for A: 1.016, P = 7.5 × 10−4). Earlier studies7,17 have seen some indication for an increased risk of influenza associated with SNPs in LD with the protective ABO lead SNP rs505922 from the HGI GWAS of earlier SARS-CoV-2 variants2. However, the lead SNP at the ABO locus in our GWAS shows no sign of association in the influenza GWAS (P = 0.215).

Open Targets Genetics analysis

To investigate connections between the 13 GWAS loci and genes based on extensive data from gene expression, protein abundance and chromatin interaction, we put the 13 lead SNPs forward to Open Targets Genetics18 (https://genetics.opentargets.org; accession date: 20 January 2025). The summary statistics from the variant-to-gene (V2G) analysis are given in Supplementary Table 7. For ABO and FUT3, relatively large V2G scores (0.47 and 0.34, respectively) were observed, while no other gene at the loci had a V2G score of >0.2. Gene connections were also observed for the SNPs at the other loci, but the V2G scores did not clearly favor single genes at those loci.

Gene-set and pathway analysis

We followed up on our GWAS with FUMA (v.1.5.2)19 for a comprehensive integration of our results with public resources, including functional annotation, expression QTL and chromatin interaction mapping, as well as additional gene-based, pathway and tissue enrichment tests (for full results, see https://fuma.ctglab.nl/browse/475677). To answer whether other traits or diseases are associated with the identified SNPs for Omicron infection, FUMA provides entries from the GWAS Catalog for SNPs in LD with the lead SNPs.

In addition, we performed a comprehensive phenome-wide association study in 2,470 phenotypes available in FinnGen release 12 for the lead SNPs (Supplementary Table 8), in which the posterior inclusion probability, calculated with SuSiE20, indicates whether our lead SNP is causal for the observed phenotype association.

The MAGMA (v.1.08)21 gene-set analysis (https://fuma.ctglab.nl/browse/475677) identified the Reactome set ‘Termination of O-glycan biosynthesis’ as the top set among a variety of 17,012 gene sets (P = 6.8 × 10−7). Among the 23 genes in this gene set are ST6GAL1 and several mucin genes, including MUC1, MUC5AC and MUC16, located in three distinct genome-wide significant loci in our study. The finding proved to be robust in a sensitivity analysis, leaving one of these four loci out at a time (see section ‘MAGMA gene-set sensitivity analysis’ in the Supplementary Note). FUMA provides the secondary analysis process, GENE2FUNC, to further investigate biological mechanisms of prioritized genes. Running GENE2FUNC for the 65 positional candidate genes from the SNP2GENE analysis, ten Reactome gene sets with an adjusted P < 0.05 were identified, eight of which are related to mucins or glycosylation (Supplementary Table 9).

Functional protein association network analysis

To find further evidence for a relevant role of genes at the identified genomic loci, we conducted a functional protein association network analysis. This approach allows for the contextualization and visualization of significant pathways while also revealing additional functional connections between proteins. To avoid retrieving associations driven solely by genes located at the same locus, we started by selecting one gene for each of our 13 GWAS loci. The resulting network has a protein–protein interaction enrichment P value of 1.33 × 10−11, indicating that these 13 proteins are at least partially biologically connected as a functional group. Seven of the 13 proteins had functional associations above the default medium confidence score threshold of 0.4, and MUC1, MUC16 and MUC5AC also interacted physically in addition to their functional associations (Fig. 2a). As mentioned above, ST6GAL1 and the three mucins are all involved in the Reactome22 pathway ‘Termination of O-glycan biosynthesis’, in which ST6GAL1 transfers sialic acid to galactose-containing acceptor substrates (here the mucins), and the connections were mainly a result of their involvement in this pathway. The connected component in this network also included FUT2, FUT3 and ABO, with the significant functional enrichment resulting from their involvement in the KEGG23 pathway ‘Glycosphingolipid biosynthesis—lacto and neolacto series’ (the only significant pathway in the specific analysis for KEGG gene sets in the secondary MAGMA analysis GENE2FUNC; adjusted P = 2.2 × 10−4). In addition to these well-established connections, there were some weaker associations between ST6GAL1, FUT2 and FUT3, as well as between FUT3 and MUC1. The former connections were a result of these proteins regulating glycosylation processes24,25, while the association between FUT3 and MUC1 was observed in aberrant glycosylation processes24. We expanded the network with 15 additional interactors at a maximum selectivity value of 1 to focus on proteins that primarily interact with the current network. For four of the identified interactors, the corresponding gene was in a genomic locus already covered. The resulting highly specific network (Fig. 2b) showed that the expansion added more proteins to the pathways already identified above and has a protein–protein interaction enrichment P value < 10−16. Among the added proteins, another sialyltransferase (ST3GAL4) was involved in both pathways and represents a strong link between the two sets of proteins.

a, STRING network for 13 genes linked to the GWAS lead SNPs. Proteins involved in the ‘Termination of O-glycan biosynthesis’ pathway are colored light green, while proteins involved in ‘Glycosphingolipid biosynthesis—lacto and neolacto series’ are colored light blue. The two sets of proteins form a connected component, with ST6GAL1 and FUT3 acting as the main bridges. The edge width is indicative of the confidence score for each association, with thicker edges denoting higher confidence scores. Proteins with no interactions are colored light gray. The resulting network can be viewed, explored and customized at https://version-12-0.string-db.org/cgi/network?networkId=bnOf0kS7q9qc. b, STRING network expanded with 15 additional interactors using a selectivity parameter of 1.0. Four interactors were removed because the corresponding genes were located in genomic loci already covered (FUT5, FUT6, MUC22, MUC3A). Additional proteins that belong to the ‘Termination of O-glycan biosynthesis’ pathway are shown in dark green, and additional proteins that belong to the ‘Glycosphingolipid biosynthesis—lacto and neolacto series’ pathway are shown in dark blue. Additional connected proteins not belonging to either of the two pathways are shown in beige. The addition of the extra proteins leads to a heavily interconnected network; for this reason, we have selected a special coloring scheme to distinguish between the different edges in the network. Solid lines represent associations between the 13 original genes and dashed lines represent associations from the 11 additional genes. Green edges show associations between the genes involved in the ‘Termination of O-glycan biosynthesis’ pathway, blue edges show associations between the genes involved in the ‘Glycosphingolipid biosynthesis—lacto and neolacto series’ pathway, and gray lines represent other associations. This network can also be accessed at https://version-12-0.string-db.org/cgi/network?networkId=bTU3KIbwyQXZ. The data underlying these networks are provided as source data.

Heritability and genetic correlations

We estimated heritability from our GWAS at the liability scale, assuming a prevalence of 0.5, as 0.024 (95% CI, 0.018–0.029), slightly higher than the heritability estimates for the HGI GWAS of infection versus population controls in European ancestry (estimates for different scenarios were all below 0.019)2.

The genetic correlation between our GWAS for infection with Omicron variants and the publicly available meta-analysis results for infection with earlier variants from the HGI for individuals of European ancestry was estimated as rg = 0.549 (95% CI, 0.342–0.757, P = 2.06 × 10−7). We also investigated genetic correlations of our GWAS with GWAS for 1,461 traits implemented in the Complex Traits Genetics Virtual Lab (https://vl.genoma.io), with most results coming from the UK Biobank. With schizophrenia, rg = −0.265 (95% CI, −0.347 to −0.182, P = 2.95 × 10−10), and asthma, rg = 0.289 (95% CI, 0.187–0.390, P = 2.67 × 10−8), two serious health conditions were among the traits reaching the adjusted significance level of 3.4 × 10−5 (Supplementary Table 10). We further investigated these genetic correlations with bivariate Gaussian mixture models implemented in MiXeR26 (v.1.3), but the model fit was poor compared to the LD score regression model (see section ‘MiXeR analyses of GWAS for infection with Omicron variants and GWAS for schizophrenia and asthma’ in the Supplementary Note). Finally, we looked up the lead SNPs from Table 1 in the GWAS of schizophrenia27 and asthma28 (Supplementary Tables 11 and 12, respectively). For asthma, two SNPs at mucin loci (MUC5AC and MUC16) show P values below the adjusted P value of 0.0038 (0.05 / 13) and agree with the top asthma SNPs at the loci. Contrary to the positive genetic correlation estimated over the whole genome, the two mucin genes have asthma ORs in the opposite direction to the Omicron infection GWAS.

Discussion

We performed a GWAS of SARS-CoV-2 infection with Omicron variants in >150,000 cases and >500,000 controls without a known SARS-CoV-2 infection from four cohorts of European ancestry and identified 13 genome-wide significant loci. The restriction to European ancestry limits the generalizability of our findings, and it will be important to study SARS-CoV-2 infection with Omicron variants at a considerable sample size in other parts of the world. Our study investigated infection during the Omicron period in general, given that information on the sub-variants of Omicron that regularly emerge was not available at an individual level. However, more than 70% of our cases were from the first 6 months of 2022, when BA variants were dominating in the study populations (see Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). Notably, our findings are corroborated by a recent GWAS of breakthrough infections16, probably dominated by Omicron infections. Breakthrough and Omicron infections are closely related in large parts of Europe and the USA, as the extensive vaccination programs rolled out in 2021 exerted strong selective pressure on the SARS-CoV-2 virus and were followed by the evolution and rapid spread of Omicron variants.

Among our findings, the most significant SNP is an intronic transversion mutation (rs13322149: G > T) located within the 148 kb ST6GAL1 gene. ST6GAL1 catalyzes the addition of terminal α2,6-sialic acids to galactose-containing N-linked glycans and is highly expressed in the liver, glandular cells in the prostate, collecting ducts and distal tubules in the kidneys and germinal centers in lymph nodes (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000073849-ST6GAL1/tissue). Expression of ST6GAL1 also enhances the concentration of six-linked sialic acid receptors that are accessible to the influenza virus on the cell surface29. Based on knowledge from other coronaviruses (including MERS-CoV recognizing α2,3-sialic acids and, to a lesser extent, the α2,6-sialic acids and sulfated sialyl-LewisX for binding preference), a role of O-acetylated sialic acids in the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into the host cell was postulated early in the pandemic30, resulting in multiple studies on the topic in a short time31.

It is evident from in vitro and in vivo studies that the emergence of Omicron changed the interaction of SARS-CoV-2 with the host. Compared to the ancestral B.1. lineage virus and the Delta variant, Omicron viral entry and infection is significantly attenuated in immortalized lung cell lines32,33,34 and human-derived lung organoids35 but increased in human-derived upper airway organoids32. In transgenic mice and Syrian hamsters, Omicron is also less pathogenic, with reduced infection and pathology in the lower airways36 but with greater affinity for tracheal cells37. The mechanism underlying this tropism shift is not fully understood. Here, the association of our ST6GAL1 SNP rs1334922 with reduced infection risk for Omicron but not pre-Omicron variants suggests an involvement of α2,6-sialic acids that emerged with the evolution of this SARS-CoV-2 variant. Considering that the same ST6GAL1 lead SNP is protective against influenza infection, a virus that enters cells through binding α2,6-sialic acids, and the dependency of other beta coronaviruses on sialic acids for host cell entry (reviewed in a previous work31) warrants a re-evaluation of the role of sialic acids in SARS-CoV-2 host cell entry for Omicron variants.

In addition to a role for host cell glycosylation in viral entry, the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is itself heavily glycosylated, with 22 N-glycosylation sites per monomer. These glycans shield the protein from the host’s humoral immune response38,39 and are generally conserved across earlier and later variants, including Omicron40,41. However, Omicron has decreased sialylation of these glycans40,42, which is speculated to reduce electrostatic repulsion and steric hindrance when binding to the ACE2 receptor and ultimately promote stronger binding between the Omicron spike and this host receptor43,44. Glycosylation near the furin cleavage site can also regulate viral activity45,46, whereby sialic acid occupancy on O-glycans decreases furin activity by up to 65% (ref. 47). Together, these results suggest that a reduction in sialic acid levels on the spike protein can enhance the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 through improved binding to the ACE2 receptor and increased furin activity.

Gene-set analysis linked ST6GAL1 to mucin genes, and our GWAS identified three loci with mucin candidate genes (MUC1, MUC5AC and MUC16), showing that the biological pathway of airway defense in mucus, linked to infections with earlier SARS-CoV-2 variants2, also has an important role in relation to Omicron variants. A recent GWAS of influenza identified two SNPs associated at genome-wide significance and, based on SARS-CoV-2 GWAS results for earlier variants, concluded that the genetic architectures of COVID-19 and influenza are mostly distinct. Our results provide nuance, as our ST6GAL1 SNP for Omicron infection was one of the two lead SNPs for influenza infection and showed a similar effect. Additionally, two of our three mucin loci had suggestive findings in the influenza GWAS.

Additional evidence for a connection between blood group systems and SARS-CoV-2 infection was obtained by three associated loci, finding the same association at the FUT2 locus determining secretor status as described for earlier variants, identifying a new locus near FUT3 and observing substantial differences at the ABO locus, where the lead SNP indicates a protective effect of blood group B. All three loci encode glycosyltransferases involved in forming blood group antigens on red blood cells, tissues and in secretions (see section ‘Discussion of the role of blood group systems in infection’ in the Supplementary Note for a discussion of the role of blood group systems in infection and the related Supplementary Fig. 5, showing ABO and Lewis blood group antigen synthesis). We want to stress that our results did not contradict the protective effect of blood group O reported for earlier variants, as the previously associated SNP was the one showing the largest difference between cases infected with Omicron variants versus controls infected with earlier variants. Furthermore, there have been association findings for several other infectious diseases at the ABO locus, as summarized in a recent influenza study7. None of the lead SNPs reported there for influenza, malaria, tonsillectomy, childhood ear infection or gastrointestinal infection are in LD with our lead SNP, rs8176741.

In conclusion, our study indicates that the human genetic architecture of SARS-CoV-2 infection is under constant development, and updated GWAS analyses for periods during which certain variants dominate can provide further insights into the biological mechanisms involved. Our results indicate that processes related to glycosylation are particularly relevant for infections with Omicron variants. Experimental studies comparing the infectivity of different SARS-CoV-2 variants in relation to host cell expression of ST6GAL1 and other mediators of glycosylation are needed to decipher the underlying biology.

Methods

Ethics

Our research complies with all relevant ethical regulations for the cohorts under study.

The Copenhagen Hospital Biobank provides biological leftover samples from routine blood analyses, and the patients were not asked for informed consent before inclusion. Instead, patients were informed about the opt-out option to have their biological specimens excluded from use in research. Individuals from the exclusion register (Vævsanvendelsesregistret) were excluded from the study. For the Danish Blood Donor Study, informed consent was obtained from all participants. Both studies are part of a COVID-19 protocol approved by the National Ethics Committee (H-21030945) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (P-2020-356).

EFTER-COVID was conducted as a surveillance study as part of Statens Serum Institut’s advisory tasks for the Danish Ministry of Health. According to Danish law, these national surveillance activities do not require approval from an ethics committee. Participation in the study was voluntary, and the invitation letter contained information about participants’ rights under the Danish General Data Protection Regulation (rights to access data, rectification, deletion, restriction of processing and objection). After reading this information, it was considered informed consent when participants read the information and agreed, and then continued to fill in the questionnaires.

The activities of the Estonian Biobank (EstBB) are regulated by the Human Genes Research Act, which was adopted in 2000 specifically for the operations of the EstBB. Individual-level analysis with EstBB data was carried out under ethical approval 1.1-12/624 from the Estonian Committee on Bioethics and Human Research (Estonian Ministry of Social Affairs), using data according to release application 6-7/GI/5933 from the EstBB.

Study participants in FinnGen provided informed consent for biobank research, based on the Finnish Biobank Act. Alternatively, separate research cohorts, collected before the Finnish Biobank Act came into effect (in September 2013) and the start of FinnGen (August 2017), were collected based on study-specific consents and later transferred to the Finnish biobanks after approval by Fimea (Finnish Medicines Agency), the National Supervisory Authority for Welfare and Health. Recruitment protocols followed the biobank protocols approved by Fimea. The Coordinating Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa statement number for the FinnGen study is HUS/990/2017. The FinnGen study is approved by the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare and other authorities (a complete overview of permissions is given in the Supplementary Data).

The Mass General Brigham (MGB) Biobank, formerly known as the Partners Biobank, is a hospital-based cohort study produced by the MGB healthcare network located in Boston, MA, USA. The MGB Biobank contains data from patients in multiple primary care facilities as well as tertiary care centers located in the greater Boston area. Participants of the study are recruited from inpatient stays, emergency department environments, outpatient visits and through a secure online portal available to patients. Recruitment and consent are fully translatable to Spanish in order to promote greater patient diversity. This allows for a systematic enrollment of diverse patient groups that is reflective of the population receiving care through the MGB network. Recruitment for the biobank began in 2009 and is still actively recruiting. The recruitment strategy has been described previously48. For the MGB Biobank, all patients provide written consent upon enrollment. Furthermore, the MGB cohort included test-verified SARS-CoV-2 infection data with time of diagnosis. The present study protocol was approved by the MGB Institutional Review Board (No. 2018P002276).

Denmark

For the Danish cohort, we combined genotype data from the Copenhagen Hospital Biobank and the Danish Blood Donor Study with information on SARS-CoV-2 infection from the EFTER-COVID study49. In short, the EFTER-COVID study invited individuals older than 15 years of age with a reverse transcription PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 infection between 1 September 2020 and 21 February 2023 to fill in a baseline and several follow-up questionnaires. Cases for SARS-CoV-2 infection with Omicron variants had their first positive test either after 28 December 2021, when more than 90% of new infections were Omicron, or earlier in December 2021, with Omicron infection confirmed by a variant-specific PCR test. Controls were individuals with a negative PCR test related to the EFTER-COVID study and no positive test result for any test in the database. For the comparison with earlier infections, controls were either defined as having a positive test before Omicron infections were observed in Denmark (21 November 2021) or infection with a non-Omicron variant confirmed by variant-specific PCR test in December 2021; individuals with a later re-infection with an Omicron variant were excluded. Basic descriptive statistics on age and sex of cases and controls from all cohorts are given in Supplementary Table 13. Genetic data for the Copenhagen Hospital Biobank and the Danish Blood Donor Study were available from genotyping with Illumina Global Screening Arrays and subsequent imputation were as previously described50,51. Data cleaning steps included filtering out individuals who were of non-European genetic ancestries (by removing outliers in a principal component analysis (PCA), deviating more than five standard deviations from one of the first five principal components), related (relatedness coefficient greater than 0.0883), having discordant sex information (chromosome aneuploidies or difference between reported sex and genetically inferred sex), were outliers for heterozygosity or having more than 3% missing genotypes. Case–control GWAS analyses were performed with REGENIE (v.2.2.4)52 under an additive model, adjusting for sex and the first five principal components. The analyses included 22,041 cases with an Omicron infection, 24,801 controls with no known infection and 18,610 controls with an infection with earlier variants.

EstBB

The EstBB is a population-based biobank with 212,955 participants in the current data freeze (2024v1). All biobank participants signed a broad informed consent form, and information on ICD-10 codes is obtained by regular linking with the national Health Insurance Fund and other relevant databases, with the majority of the electronic health records having been collected since 2004 (ref. 53). COVID-19 data were acquired from electronic health records (ICD-10 U07* category), with diagnoses between 1 March 2020 through 30 November 2021 being considered as cases with non-Omicron variants, while cases from 1 January 2022 through 31 December 2022 were considered to be Omicron cases. Participants with diagnoses from both periods were excluded. Controls without any U07* category diagnoses were considered healthy.

All EstBB participants were genotyped at the Core Genotyping Lab of the Institute of Genomics, University of Tartu, using Illumina Global Screening Array v3.0_EST. Samples were genotyped and PLINK format files were created using Illumina GenomeStudio (v.2.0.4). Individuals were excluded from the analysis if their call rate was <95%, if they were outliers of the absolute value of heterozygosity (>3 s.d. from the mean) or if sex defined based on heterozygosity of the X chromosome did not match sex in phenotype data54. Before imputation, variants were filtered by call rate of <95%, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium P value of <1 × 10−4 (autosomal variants only) and minor allele frequency of <1%. Genotyped variant positions were in build 37 and were lifted over to build 38 using Picard (v.2.26.2). Phasing was performed using Beagle (v.5.4) software55. Imputation was performed with Beagle (v.5.4) software (beagle.22Jul22.46e.jar) and default settings. The dataset was split into batches of 5,000. A population-specific reference panel consisting of 2,695 whole-genome sequencing samples was used for imputation, and standard Beagle hg38 recombination maps were used. Based on PCA, samples that were not of European ancestry were removed. Duplicate and monozygous twin detection was performed with KING (v.2.2.7)56, and one sample was removed from the pair of duplicates.

Association analysis in EstBB was carried out for all variants with an INFO score of >0.4 using the additive model as implemented in REGENIE (v.3.0.3), with standard binary trait settings52. Logistic regression was carried out with adjustment for current age, age2, sex and ten principal components as covariates, analyzing only variants with a minimum minor allele count of two. The analyses included 61,181 cases with an Omicron infection, 93,852 controls with no known infection and 28,031 controls with an infection with earlier variants.

FinnGen

Finnish ancestry samples from the Finnish public–private research project FinnGen were used57. FinnGen (release 12) comprises genome information with digital healthcare data on ~10% of the Finnish population (https://www.finngen.fi/en). Individuals in FinnGen (release 12) with the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis code U07* for SARS-CoV-2 infection (U07.1 or U07.2, virus identified or not identified, respectively) were defined as SARS-CoV-2-infected. For the GWAS of Omicron, individuals were grouped by the diagnosis date of their first SARS-CoV-2 infection. As Omicron variants became the main lineage in December 2021 in Finland, we defined individuals with their first SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis date starting from 1 January 2022 as Omicron cases (n = 61,393). Individuals with no SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis were used as controls (n = 399,149). For the comparison with earlier SARS-CoV-2 variants, individuals with diagnosis dates before or in November 2021 and no later re-infection with an Omicron variant were defined as controls (n = 35,594). Diagnosis dates in FinnGen data are pseudonymised by ±2 weeks; thus, individuals with their first SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis during the Delta–Omicron transition period, December 2021, were excluded from the earlier SARS-CoV-2 controls.

FinnGen samples were genotyped with ThermoFisher, Illumina and Affymetrix arrays. Imputation was performed using the Finnish population-specific imputation panel SISu v4 (v.4.2). FinnGen data (180,000 SNPs) were compared to 1000 Genomes Project data, with a Bayesian algorithm detecting PCA outliers. A total of 35,371 samples were detected as either non-Finnish ancestry or as twins or duplicates with relations to other samples, and thus excluded. Of the 500,737 non-duplicate population inlier samples from PCA, 355 samples were excluded from analysis because of missing minimum phenotype data, and 34 samples were removed because of failing sex check, with F thresholds of 0.4 and 0.7. A total of 500,348 samples (282,064 (56.4%) females and 218,284 (43.6%) males) were accepted for phenotyping for the GWAS analyses.

Case versus control GWAS analyses were performed using REGENIE (v.2.2.4)52. Logistic regression was adjusted for age (at death or end of registry follow-up), sex, the first ten principal components and genotyping batches. The Firth approximation test was applied for variants with an initial P value of <0.01, and standard error was computed based on the effect size and likelihood ratio test P value (REGENIE options –firth –approx –pThresh 0.01 –firth-se). The analyses included 61,393 cases with an Omicron infection, 399,149 controls with no known infection and 35,594 controls with an infection with earlier variants.

MGB Biobank

Cases for SARS-CoV-2 infection with Omicron variants were ascertained from the MGB Biobank (data access 23 April 2024). Individuals with a SARS-CoV-2 infection were curated by the biobank and represent those who presented to the hospital system with a positive infection control flag, presumed infection control flag and/or a SARS-CoV-2 RNA positive test result. Cases of Omicron infections were defined as individuals presenting with a SARS-CoV-2 infection after 1 January 2022. The control definition included individuals in the MGB Biobank without any report of infection. For the comparison of infections with earlier variants, controls were defined as individuals with a SARS-CoV-2 infection before 1 December 2021 and no later re-infection with an Omicron variant.

The MGB Biobank genotyped 53,297 participants on the Illumina Global Screening Array and 11,864 on Illumina Multi-Ethnic Global Array. The global screening arrays captured approximately 652,000 SNPs and short insertions and deletions, while the multi-ethnic global arrays captured approximately 1.38 million SNPs and short insertions and deletions. These genotypes were filtered for high missingness (>2%) and variants out of Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P < 1 × 10−12), as well as variants with an allele frequency discordant (P < 1 × 100−150) from a synthesized allele frequency calculated from GnomAD subpopulation frequencies and a genome-wide GnomAD model fit of the entire cohort. This resulted in approximately 620,000 variants for the global screening array and 1.15 million for the multi-ethnic global array. The two sets of genotypes were then separately phased and imputed on the TOPMed imputation server (Minimac4 algorithm) using the TOPMed r2 reference panel. The resultant imputation sets were both filtered at an R2 > 0.4 and a minor allele frequency of >0.001, and then the two sets were merged or intersected, resulting in approximately 19.5 million GRCh38 autosomal variants. The sample set for analysis here was then restricted to just those classified as European according to a random forest classifier trained with the Human Genome Diversity Project as the reference panel, with the minimum probability for assignment to an ancestral group of 0.5, in 19 out of 20 iterations of the model48. To correct for population stratification, principal components were computed in genetically European participants. Association analysis was performed with variants using REGENIE (v.3.2.8) with adjustment for age, age2, sex, chip, tranche and PC 1-10. The analyses included 7,220 cases with an Omicron infection, 38,843 controls with no known infection and 4,977 controls with an infection with earlier variants.

Meta-analysis

Initial REGENIE results were filtered based on a minor allele frequency of >0.1% and an INFO score of >0.8 and analyzed in METAL (v.2011.03.25)58 by the inverse-variance method with genomic control applied to the input files. Heterogeneity of the effects across cohorts was tested with the I2 statistic and Cochran’s Q-test for heterogeneity. The results from the meta-analysis were filtered for SNPs present in all three major cohorts, resulting in a total of 8,669,333 SNPs, of which 436,360 did not have results for the MGB cohort (including all 224,900 SNPs from chromosome X).

LD calculations

When not otherwise stated, LD between SNPs was calculated in LDpair (https://ldlink.nih.gov/?tab=ldpair) based on the five European ancestry groups from Utah, Italy, Finland, Great Britain and Spain. In cases for which one of the SNPs was not available in the 1000 Genomes Project reference panel, LD was calculated based on the Danish study cohort.

Open Targets Genetics analysis

The V2G analysis pipeline in Open Target Genetics18 provides a single aggregated score for each variant–gene prediction based on four different data types: molecular phenotype quantitative trait loci datasets (expression and protein QTLs), chromatin interaction and conformation datasets, in silico functional predictions (using the Variant Effect Predictor score59) and distance from the canonical transcript start site. V2G scores range from zero to one, with higher scores indicating stronger variant–gene links.

FUMA and MAGMA analyses

FUMA is an integrative web-based platform using information from multiple biological resources to provide functional annotation of GWAS results, positional, expression QTL and chromatin interaction mappings, gene prioritization and gene-based, pathway and tissue enrichment results19. MAGMA is a method developed for gene and gene-set analyses to provide deeper insight into functional and biological mechanisms underlying complex traits21. We ran FUMA and the implemented version of MAGMA in one FUMA job (link provided in Data availability).

MiXeR analysis

To further evaluate the observed genetic correlations between omicron infection and schizophrenia and asthma, we applied univariate and bivariate Gaussian mixture modeling as implemented in MiXeR26 (v.1.3) to summary statistics for each trait. In its univariate form, MiXeR analyzes GWAS summary statistics by modeling SNP effects as a mixture: combining a point mass at zero (representing non-causal variants) with a continuous distribution for non-zero, causal effects. This enables estimates of polygenicity (the number of causal variants) and discoverability (the variance of their effect sizes). Its bivariate extension simultaneously examines two traits, decomposing their genetic signals into shared and trait-specific components. This joint analysis not only estimates the overall genetic correlation between traits but also quantifies how many causal variants contribute to both traits versus those that are unique.

STRING functional protein association network analysis

The STRING database compiles and integrates protein–protein associations from various sources to create comprehensive global interaction networks. STRING assigns confidence scores to all protein–protein associations, estimating the likelihood of their accuracy based on available evidence60. These precomputed scores range from zero to one and are provided separately for physical and functional associations. To determine these scores, evidence is categorized into seven channels, including co-expression, experimental data, curated databases and text mining. STRING calculates confidence scores for each evidence channel by first quantifying interaction evidence with channel-specific metrics and then converting these into likelihoods using calibration curves based on KEGG pathway data61. These scores are then transferred to related protein pairs in other organisms and, finally, a combined confidence score is generated by probabilistically integrating the individual channel scores, assuming their independence. Users can rely on this combined score for network exploration or customize their analyses by enabling or disabling specific channels. STRING also provides a protein–protein interaction enrichment P value to investigate whether the proteins in the network exhibit more interactions among themselves than would be expected by chance for a randomly selected, equally sized set of proteins with the same degree (that is, number of connections per protein) distribution from the genome. An independent benchmark has shown that STRING is among the top-performing molecular networks in human disease research62.

For our analysis, we obtained functional protein association networks from STRING database v.12 (ref. 61), which we visualized in Cytoscape v.3.10 (ref. 63) using stringApp v.2.1.1 (ref. 64). Initially, we selected one gene per locus (based on candidacy from physical proximity to the lead SNP or additional evidence from FUMA and Open Targets Genetics results) and used the default confidence score threshold of 0.4, indicating medium interaction confidence.

One functionality of STRING is expanding a given network with a user-defined number of interactors at a specific degree of selectivity64. We expanded the initial network with 15 interactors, setting the selectivity parameter to the maximum value of 1, allowing us to identify proteins that primarily interact with the current network and are not hubs of the entire STRING network. The genes for some of the 15 retrieved interactors were located at the same locus, or at a locus already represented in the initial network. In these cases, we selected only the entry with the most interactions in the network and removed the other proteins at this locus from the network for our analysis.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics are publicly available for interactive plotting, viewing and downloading through LocusZoom65 (https://my.locuszoom.org/gwas/962995) and are also deposited at the Danish National Biobank (https://www.danishnationalbiobank.com/gwas/glycosylation-and-omicron-variants). Complete FUMA results (including the MAGMA analysis) are available online (https://fuma.ctglab.nl/browse/475677). The STRING network for 13 genes linked to the GWAS lead SNPs can be found at https://version-12-0.string-db.org/cgi/network?networkId=bnOf0kS7q9qc; the STRING network expanded with 15 additional interactors can be found at https://version-12-0.string-db.org/cgi/network?networkId=bTU3KIbwyQXZ. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code for the analysis is available at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17348245)66.

References

World Health Organization. COVID-19 cases. WHO COVID-19 dashboard. https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases (2025).

Kanai, M. et al. A second update on mapping the human genetic architecture of COVID-19. Nature 621, E7–E26 (2023).

Markov, P. V. et al. The evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 361–379 (2023).

Azad, M. B., Wade, K. H. & Timpson, N. J. FUT2 secretor genotype and susceptibility to infections and chronic conditions in the ALSPAC cohort. Wellcome Open Res. 3, 65 (2018).

Tian, C. et al. Genome-wide association and HLA region fine-mapping studies identify susceptibility loci for multiple common infections. Nat. Commun. 8, 599 (2017).

Jones, M. B. IgG and leukocytes: targets of immunomodulatory α2,6 sialic acids. Cell. Immunol. 333, 58–64 (2018).

Kosmicki, J. A. et al. Genetic risk factors for COVID-19 and influenza are largely distinct. Nat. Genet. 56, 1592–1596 (2024).

Emilsson, V. et al. Co-regulatory networks of human serum proteins link genetics to disease. Science 361, 769–773 (2018).

Keaton, J. M. et al. Genome-wide analysis in over 1 million individuals of European ancestry yields improved polygenic risk scores for blood pressure traits. Nat. Genet. 56, 778–791 (2024).

Sakaue, S. et al. A cross-population atlas of genetic associations for 220 human phenotypes. Nat. Genet. 53, 1415–1424 (2021).

Shrine, N. et al. New genetic signals for lung function highlight pathways and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associations across multiple ancestries. Nat. Genet. 51, 481–493 (2019).

Paganini, J. et al. HLA-F transcriptional and protein differential expression according to its genetic polymorphisms. HLA 102, 578–589 (2023).

Lin, A. & Yan, W. H. The emerging roles of human leukocyte antigen-F in immune modulation and viral infection. Front. Immunol. 10, 449250 (2019).

Noh, H. E. & Rha, M. S. Mucosal immunity against SARS-CoV-2 in the respiratory tract. Pathogens 13, 113 (2024).

Gram, M. A. et al. Patterns of testing in the extensive Danish national SARS-CoV-2 test set-up. PLoS ONE 18, e0281972 (2023).

Alcalde-Herraiz, M. et al. Genome-wide association studies of COVID-19 vaccine seroconversion and breakthrough outcomes in UK Biobank. Nat. Commun. 15, 8739 (2024).

Shelton, J. F. et al. Trans-ancestry analysis reveals genetic and nongenetic associations with COVID-19 susceptibility and severity. Nat. Genet. 53, 801–808 (2021).

Ghoussaini, M. et al. Open Targets Genetics: systematic identification of trait-associated genes using large-scale genetics and functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D1311–D1320 (2021).

Watanabe, K., Taskesen, E., van Bochoven, A. & Posthuma, D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat. Commun. 8, 1826 (2017).

Wang, G., Sarkar, A., Carbonetto, P. & Stephens, M. A simple new approach to variable selection in regression, with application to genetic fine mapping. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B Stat. Methodol. 82, 1273–1300 (2020).

de Leeuw, C. A., Mooij, J. M., Heskes, T. & Posthuma, D. MAGMA: generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 11, e1004219 (2015).

Milacic, M. et al. The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, D672–D678 (2024).

Kanehisa, M., Goto, S., Sato, Y., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D109–D114 (2012).

Fernández-Ponce, C. et al. The role of glycosyltransferases in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 5822 (2021).

Zhu, J., Dingess, K. A., Mank, M., Stahl, B. & Heck, A. J. R. Personalized profiling reveals donor- and lactation-specific trends in the human milk proteome and peptidome. J. Nutr. 151, 826–839 (2021).

Frei, O. et al. Bivariate causal mixture model quantifies polygenic overlap between complex traits beyond genetic correlation. Nat. Commun. 10, 2417 (2019).

Ripke, S. et al. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 511, 421–427 (2014).

Zhou, W. et al. Global Biobank Meta-analysis Initiative: powering genetic discovery across human disease. Cell Genomics 2, 100192 (2022).

Matrosovich, M., Matrosovich, T., Carr, J., Roberts, N. A. & Klenk, H.-D. Overexpression of the α-2,6-sialyltransferase in MDCK cells increases influenza virus sensitivity to neuraminidase inhibitors. J. Virol. 77, 8418 (2003).

Kim, C. H. SARS-CoV-2 evolutionary adaptation toward host entry and recognition of receptor O-acetyl sialylation in virus–host interaction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 4549 (2020).

Sun, X. L. The role of cell surface sialic acids for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Glycobiology 31, 1245–1253 (2021).

Mykytyn, A. Z. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron entry is type II transmembrane serine protease-mediated in human airway and intestinal organoid models. J. Virol. 97, e0085123 (2023).

Willett, B. J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron is an immune escape variant with an altered cell entry pathway. Nat. Microbiol. 7, 1161–1179 (2022).

Laine, L., Skön, M., Väisänen, E., Julkunen, I. & Österlund, P. SARS-CoV-2 variants Alpha, Beta, Delta and Omicron show a slower host cell interferon response compared to an early pandemic variant. Front. Immunol. 13, 1016108 (2022).

Flagg, M. et al. Low level of tonic interferon signalling is associated with enhanced susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in human lung organoids. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 12, 2276338 (2023).

Halfmann, P. J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron virus causes attenuated disease in mice and hamsters. Nature 603, 687–692 (2022).

Armando, F. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant causes mild pathology in the upper and lower respiratory tract of hamsters. Nat. Commun. 13, 3519 (2022).

Watanabe, Y., Bowden, T. A., Wilson, I. A. & Crispin, M. Exploitation of glycosylation in enveloped virus pathobiology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1863, 1480–1497 (2019).

Casalino, L. et al. Beyond shielding: the roles of glycans in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. ACS Cent. Sci. 6, 1722–1734 (2020).

Shajahan, A., Pepi, L. E., Kumar, B., Murray, N. B. & Azadi, P. Site specific N- and O-glycosylation mapping of the spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Sci. Rep. 13, 10053 (2023).

Wang, D. et al. Enhanced surface accessibility of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron spike protein due to an altered glycosylation profile. ACS Infect. Dis. 13, 23 (2024).

Xie, Y. & Butler, M. Quantitative profiling of N-glycosylation of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein variants. Glycobiology 33, 188–202 (2023).

Huang, C. et al. The effect of N-glycosylation of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein on the virus interaction with the host cell ACE2 receptor. iScience 24, 103272 (2021).

Zheng, L. et al. Characterization and function of glycans on the spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e0312022 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. Sequential glycosylations at the multibasic cleavage site of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein regulate viral activity. Nat. Commun. 15, 4162 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. Furin cleavage of the SARS-CoV-2 spike is modulated by O-glycosylation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2109905118 (2021).

Gonzalez-Rodriguez, E. et al. O-Linked sialoglycans modulate the proteolysis of SARS-CoV-2 spike and likely contribute to the mutational trajectory in variants of concern. ACS Cent. Sci. 9, 393–404 (2023).

Dashti, H. S. et al. Interaction of obesity polygenic score with lifestyle risk factors in an electronic health record biobank. BMC Med. 20, 5 (2022).

Sørensen, A. I. V. et al. Cohort profile: EFTER-COVID—a Danish nationwide cohort for assessing the long-term health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open 14, e087799 (2024).

Sørensen, E. et al. Data Resource Profile: The Copenhagen Hospital Biobank (CHB). Int. J. Epidemiol. 50, 719–720e (2021).

Hansen, T. F. et al. DBDS Genomic Cohort, a prospective and comprehensive resource for integrative and temporal analysis of genetic, environmental and lifestyle factors affecting health of blood donors. BMJ Open 9, e028401 (2019).

Mbatchou, J. et al. Computationally efficient whole-genome regression for quantitative and binary traits. Nat. Genet. 53, 1097–1103 (2021).

Leitsalu, L. et al. Cohort Profile: Estonian Biobank of the Estonian Genome Center, University of Tartu. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 1137–1147 (2015).

Mitt, M. et al. Improved imputation accuracy of rare and low-frequency variants using population-specific high-coverage WGS-based imputation reference panel. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 25, 869–876 (2017).

Browning, B. L., Tian, X., Zhou, Y. & Browning, S. R. Fast two-stage phasing of large-scale sequence data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 108, 1880–1890 (2021).

Manichaikul, A. et al. Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics 26, 2867–2873 (2010).

Kurki, M. I. et al. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature 613, 508–518 (2023).

Willer, C. J., Li, Y. & Abecasis, G. R. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics 26, 2190–2191 (2010).

McLaren, W. et al. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol. 17, 122 (2016).

von Mering, C. et al. STRING: known and predicted protein–protein associations, integrated and transferred across organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, D433–D437 (2005).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein–protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D638–D646 (2023).

Huang, J. K. et al. Systematic evaluation of molecular networks for discovery of disease genes. Cell Syst. 6, 484–495.e5 (2018).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504 (2003).

Doncheva, N. T. et al. Cytoscape stringApp 2.0: analysis and visualization of heterogeneous biological networks. J. Proteome Res. 22, 637–646 (2023).

Boughton, A. P. et al. LocusZoom.js: interactive and embeddable visualization of genetic association study results. Bioinformatics 37, 3017–3018 (2021).

Geller, F. Custom software scripts for Geller et al.: ‘Central role of glycosylation processes in human genetic susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infections with Omicron variants’. Zenodo https://zenodo.org/records/17348245 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants and staff related to the Copenhagen Hospital Biobank, Danish Blood Donor Study, EFTER-COVID, FinnGen, EstBB and MGB Biobank for their contribution to this research. This work was supported in full or in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01AI170850 (J.V.); Novo Nordisk Foundation NNF22OC0077221 and NNF23OC0087269 (S. Bliddal); NordForsk project nos. 105668 and 138929 (L.A.N.C.); NIH R35GM146839 (J.M.L.) and NIH R01HG012810 (J.M.L.); the Academy of Finland no. 353812 (H.M.O.), NIH R01AI170850 (H.M.O.), EU Horizon Europe research and innovation programme 101057553 (H.M.O.) and the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation, contract number 22.00094 (H.M.O.); and Novo Nordisk Foundation NNF17OC0027594 (B.F.). This work was also supported by research grants from Sygeforsikringen “danmark” 2020-0178 and the EU Horizon REACT study 101057129. The Copenhagen Hospital Biobank was funded by grants from Novo Nordisk Foundation NNF23OC0082015 and Rigshospitalet Research Council (Framework grant) and by Novo Nordisk Foundation CHALLENGE grant NNF17OC0027594. The Danish Blood Donor Study was funded by the Danish Council for Independent Research—Medical Sciences and the Danish Administrative Regions (Bio- and Genome Bank Denmark). The Danish Departments of Clinical Microbiology and Statens Serum Institut carried out laboratory analyses, registration and release of the national SARS-CoV-2 surveillance data for the present study. The work of the Estonian Genome Center, University of Tartu, was funded by the European Union through the Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant nos. 894987, 101137201 and 101137154 and Estonian Research Council Grant PRG1291. The Estonian Genome Center analyses were partially carried out in the High Performance Computing Center, University of Tartu. We acknowledge the participants and investigators of the FinnGen study. The FinnGen project is funded by two grants from Business Finland (HUS 4685/31/2016 and UH 4386/31/2016) and the following industry partners: AbbVie, AstraZeneca UK, Biogen MA, Bristol Myers Squibb (and Celgene Corporation & Celgene International II Sàrl), Genentech, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline Intellectual Property Development, Sanofi US Services, Maze Therapeutics, Janssen Biotech, Novartis and Boehringer Ingelheim International. The following biobanks are acknowledged for delivering biobank samples to FinnGen: Auria Biobank (www.auria.fi/biopankki), THL Biobank (www.thl.fi/biobank), Helsinki Biobank (www.helsinginbiopankki.fi), Biobank Borealis of Northern Finland (https://www.ppshp.fi/Tutkimus-ja-opetus/Biopankki/Pages/Biobank-Borealis-briefly-in-English.aspx), Finnish Clinical Biobank Tampere (www.tays.fi/en-US/Research_and_development/Finnish_Clinical_Biobank_Tampere), Biobank of Eastern Finland (www.ita-suomenbiopankki.fi/en), Central Finland Biobank (www.ksshp.fi/fi-FI/Potilaalle/Biopankki), Finnish Red Cross Blood Service Biobank (www.veripalvelu.fi/verenluovutus/biopankkitoiminta), Terveystalo Biobank (www.terveystalo.com/fi/Yritystietoa/Terveystalo-Biopankki/Biopankki) and Arctic Biobank (https://www.oulu.fi/en/university/faculties-and-units/faculty-medicine/northern-finland-birth-cohorts-and-arctic-biobank). All Finnish Biobanks are members of BBMRI.fi infrastructure (https://www.bbmri-eric.eu/national-nodes/finland). Finnish Biobank Cooperative—FINBB (https://finbb.fi) is the coordinator of BBMRI-ERIC operations in Finland. The Finnish biobank data can be accessed through the Fingenious services (https://site.fingenious.fi/en) managed by FINBB. We thank the MGB Biobank for providing samples, genomic data and health information data for genetic analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

F.G. conceptualized the study, coordinated the analyses and wrote the first manuscript draft. F.G., X.W., V.L., E.A., H.M.O. and B.F. designed the analyses and interpreted the results. F.G., X.W., V.L., E.A., J.T.V., K.N., A.B., N.W.A., L.Q. and J.M.L. analyzed the data. M.R. and R.L. interpreted results in the context of viral immunology. B.A., K.B., S. Bliddal, L.B., S. Brunak, N.B., J.B.-G., L.A.N.C., M.D., K.M.D., C.E., U.F.-R., K.G., K.A.K., C.M., C.H.N., H.S.N., S.D.N., J.N., C.B.S., N.T., H.U., L.S., P.B., A.H., E.S., O.B.P. and S.R.O. provided data from the Danish study groups. H.M.O., S.R.O. and B.F. jointly supervised the study. All authors contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S. Brunak has ownerships in Intomics, Hoba Therapeutics, Novo Nordisk, Lundbeck, ALK abello, Eli Lilly and Co. and managing board memberships in Proscion and Intomics. C.E. has received unrestricted research grants from Novo Nordisk, administered by Aarhus University, and Abbott Diagnostics, administered by Aarhus University Hospital. C.E. received no personal fees. K.G. received a Janssen Pharma research grant and is on the advisory board of Otsuka Pharma. L.B. currently works for MSD Denmark. All other authors report no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Genetics thanks Manuel Ferreira, Janie Shelton and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–5, Supplementary Note.

Supplementary Data

List of members of the Danish Blood Donor Study Genomic Consortium, Estonian Biobank Research Team and FinnGen; permissions for FinnGen.

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Tables 1–13.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

List of interactions depicted in Fig. 2a. The thickness of edges is determined by the confidence scores in the last column ‘combined_score’.

Source Data Fig. 2

List of interactions depicted in Fig. 2b. The thickness of edges is determined by the confidence scores in the last column ‘combined_score’.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Geller, F., Wu, X., Lammi, V. et al. Central role of glycosylation processes in human genetic susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infections with Omicron variants. Nat Genet (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-025-02484-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-025-02484-9