Abstract

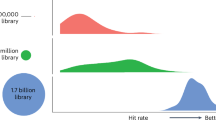

Recently, ‘tangible’ virtual libraries have made billions of molecules readily available. Prioritizing these molecules for synthesis and testing demands computational approaches, such as docking. Their success may depend on library diversity, their similarity to bio-like molecules and how receptor fit and artifacts change with library size. We compared a library of 3 million ‘in-stock’ molecules with billion-plus tangible libraries. The bias toward bio-like molecules in the tangible library decreases 19,000-fold versus those ‘in-stock’. Similarly, thousands of high-ranking molecules, including experimental actives, from five ultra-large-library docking campaigns are also dissimilar to bio-like molecules. Meanwhile, better-fitting molecules are found as the library grows, with the score improving log-linearly with library size. Finally, as library size increases, so too do rare molecules that rank artifactually well. Although the nature of these artifacts changes from target to target, the expectation of their occurrence does not, and simple strategies can minimize their impact.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The compounds docked in this study are freely available from our ZINC20 and ZINC22 databases, https://zinc20.docking.org and https://cartblanche22.docking.org. Bio-like molecules for similarity comparison are freely available from the ZINC15 database: https://zinc15.docking.org/substances/subsets/world/ for the worldwide drug set and https://zinc15.docking.org/substances/subsets/biogenic/ for the biogenic set. PDB codes associated with this study are: 5WIU (the D4 receptor), 7MFI (the σ2 receptor) and 6WHA (the 5HT2A receptor). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

DOCK3.8 is freely available for non-commercial research https://dock.compbio.ucsf.edu/DOCK3.8/. A web-based version is available at https://blaster.docking.org/. The tool to measure Tanimoto coefficient is freely accessible at https://github.com/docking-org/ChemInfTools.

References

Bohacek, R. S., McMartin, C. & Guida, W. C. The art and practice of structure‐based drug design: a molecular modeling perspective. Med. Res. Rev. 16, 3–50 (1996).

Fink, T., Bruggesser, H. & Reymond, J. L. Virtual exploration of the small‐molecule chemical universe below 160 daltons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 44, 1504–1508 (2005).

Wilhelm, S. et al. Discovery and development of sorafenib: a multikinase inhibitor for treating cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5, 835–844 (2006).

Macarron, R. et al. Impact of high-throughput screening in biomedical research. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 10, 188–195 (2011).

Brown, D. G. & Boström, J. Where do recent small molecule clinical development candidates come from? J. Med. Chem. 61, 9442–9468 (2018).

Hert, J., Irwin, J. J., Laggner, C., Keiser, M. J. & Shoichet, B. K. Quantifying biogenic bias in screening libraries. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 479–483 (2009).

Martin, Y. C. Diverse viewpoints on computational aspects of molecular diversity. J. Comb. Chem. 3, 231–250 (2001).

Breinbauer, R., Vetter, I. R. & Waldmann, H. From protein domains to drug candidates—natural products as guiding principles in the design and synthesis of compound libraries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 41, 2878–2890 (2002).

Koehn, F. E. & Carter, G. T. The evolving role of natural products in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 4, 206–220 (2005).

Arve, L., Voigt, T. & Waldmann, H. Charting biological and chemical space: PSSC and SCONP as guiding principles for the development of compound collections based on natural product scaffolds. QSAR Comb. Sci. 25, 449–456 (2006).

Ertl, P., Roggo, S. & Schuffenhauer, A. Natural product-likeness score and its application for prioritization of compound libraries. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 48, 68–74 (2008).

Gupta, S. & Aires-de-Sousa, J. Comparing the chemical spaces of metabolites and available chemicals: models of metabolite-likeness. Mol. Diversity 11, 23–36 (2007).

Bon, R. S. & Waldmann, H. Bioactivity-guided navigation of chemical space. Acc. Chem. Res. 43, 1103–1114 (2010).

Lenci, E. & Trabocchi, A. Diversity‐oriented synthesis and chemoinformatics: a fruitful synergy towards better chemical libraries. Eur. J. Org. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejoc.202200575 (2022).

Grigalunas, M., Brakmann, S. & Waldmann, H. Chemical evolution of natural product structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 3314–3329 (2022).

Rodrigues, T., Reker, D., Schneider, P. & Schneider, G. Counting on natural products for drug design. Nat. Chem. 8, 531–541 (2016).

Chen, Y., de Bruyn Kops, C. & Kirchmair, J. Data resources for the computer-guided discovery of bioactive natural products. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 57, 2099–2111 (2017).

Petrone, P. M. et al. Biodiversity of small molecules—a new perspective in screening set selection. Drug Discov. Today 18, 674–680 (2013).

Oprea, T. I. Property distribution of drug-related chemical databases. J. Comput. Aid. Mol. Des. 14, 251–264 (2000).

Warr, W. A., Nicklaus, M. C., Nicolaou, C. A. & Rarey, M. Exploration of ultralarge compound collections for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 62, 2021–2034 (2022).

Alon, A. et al. Structures of the σ2 receptor enable docking for bioactive ligand discovery. Nature 600, 759–764 (2021).

Lyu, J. et al. Ultra-large library docking for discovering new chemotypes. Nature 566, 224–229 (2019).

Gorgulla, C. et al. An open-source drug discovery platform enables ultra-large virtual screens. Nature 580, 663–668 (2020).

Sadybekov, A. A. et al. Synthon-based ligand discovery in virtual libraries of over 11 billion compounds. Nature 601, 452–459 (2022).

Stein, R. M. et al. Virtual discovery of melatonin receptor ligands to modulate circadian rhythms. Nature 579, 609–614 (2020).

Grebner, C. et al. Virtual screening in the cloud: how big is big enough? J. Chem. Inf. Model. 60, 4274–4282 (2019).

Walters, W. P. Virtual chemical libraries: miniperspective. J. Med. Chem. 62, 1116–1124 (2018).

Irwin, J. J. et al. An aggregation advisor for ligand discovery. J. Med. Chem. 58, 7076–7087 (2015).

Venkatakrishnan, A. et al. Molecular signatures of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature 494, 185–194 (2013).

Munk, C. et al. An online resource for GPCR structure determination and analysis. Nat. Methods 16, 151–162 (2019).

Schuller, M. et al. Fragment binding to the Nsp3 macrodomain of SARS-CoV-2 identified through crystallographic screening and computational docking. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf8711 (2021).

Lipinski, C. A. Physicochemical properties and the discovery of orally active drugs: technical and people issues. In Molecular Informatics: Confronting Complexity, Proceedings of the Beilstein-Institut Workshop (Frankfurt, 2003).

Lipinski, C. A., Lombardo, F., Dominy, B. W. & Feeney, P. J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 23, 3–25 (1997).

QikProp (Schrödinger, LLC, 2021).

Hann, M. M. & Oprea, T. I. Pursuing the leadlikeness concept in pharmaceutical research. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 8, 255–263 (2004).

Singh, I. et al. Structure-based discovery of conformationally selective inhibitors of the serotonin transporter. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.13.495991 (2022).

Fink, E. A. et al. Structure-based discovery of nonopioid analgesics acting through the α2A-adrenergic receptor. Science 377, eabn7065 (2022).

Bemis, G. W. & Murcko, M. A. The properties of known drugs. 1. Molecular frameworks. J. Med. Chem. 39, 2887–2893 (1996).

Gu, S., Smith, M. S., Yang, Y., Irwin, J. J. & Shoichet, B. K. Ligand strain energy in large library docking. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 61, 4331–4341 (2021).

Bender, B. J. et al. A practical guide to large-scale docking. Nat. Protoc. 16, 4799–4832 (2021).

Bellmann, L., Penner, P., Gastreich, M. & Rarey, M. Comparison of combinatorial fragment spaces and its application to ultralarge make-on-demand compound catalogs. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 62, 553–566 (2022).

Shoichet, B. K. & Kuntz, I. D. Matching chemistry and shape in molecular docking. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 6, 723–732 (1993).

Gallagher, K. & Sharp, K. Electrostatic contributions to heat capacity changes of DNA-ligand binding. Biophys. J. 75, 769–776 (1998).

Meng, E. C., Shoichet, B. K. & Kuntz, I. D. Automated docking with grid‐based energy evaluation. J. Comput. Chem. 13, 505–524 (1992).

Mysinger, M. M. & Shoichet, B. K. Rapid context-dependent ligand desolvation in molecular docking. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 50, 1561–1573 (2010).

Southan, C. et al. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D1054–D1068 (2016).

Mendez, D. et al. ChEMBL: towards direct deposition of bioassay data. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D930–D940 (2019).

Stein, R. M. et al. Property-unmatched decoys in docking benchmarks. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 61, 699–714 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by US NIH grant nos. R35GM122481 (to B.K.S.) and GM133836 (to J.J.I.). We thank OpenEye Software for the use of Omega and Schrödinger LLC for the use of prepwizard, LigPrep and QikProp in Maestro. We thank K. Tang, B. Tingle and J. Castanon for helping with calculations. We thank T. Tummino and S. Gahbauer for reading this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. performed computational docking and chemoinformatic analysis, prepared figures and co-wrote the manuscript. J.J.I. developed docking libraries, edited the manuscript and arranged funding. B.K.S. supervised the work, co-wrote the manuscript and conceived the study with the other authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

B.K.S. is a co-founder of BlueDolphin, LLC, a molecular docking contract research organization, Epiodyne and Deep Apple Therapeutics, Inc., both drug discovery companies, has recently consulted for Umbra, Abbvie and Dice Therapeutics, and is on the Scientific Advisory Board of Schrödinger. J.J.I. co-founded Deep Apple Therapeutics, Inc. and BlueDolphin, LLC. J.L. declares no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemical Biology thanks Artem Cherkasov and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 The distribution of docking-prioritized and experimentally active (blue) and non-active (orange) molecules from two different docking campaigns as a function of the Tanimoto similarity to their nearest neighbor in the bio-like molecule set.

The docking campaigns from left to right are a. the melatonin receptor and b. the Nsp3 macrodomain.

Extended Data Fig. 2 The distribution of in-stock (grey) and make-on-demand (black) libraries as a function of physical properties.

a. cLogP, b. number of rotatable bonds, c. tPSA, d. net charge. The Y axis is in log10 scale for all the panels on the left while the Y axis is linear for all the panels on the right. Results are mean ± standard deviation.

Extended Data Fig. 3 The distribution of in-stock bio-like molecules (grey) and lead-like make-on-demand molecules (black) as a function of physical properties.

a. cLogP, b. number of rotatable bonds, c. tPSA, d. net charge, e. number of violations on Lipinski’s rule of five and f. number of violations on Jorgensen’s rule of three. For Extended Data Fig. 2a−c, the Y axis on the left is in log10 scale while the Y axis on the right is linear. For Extended Data Fig. 2d−f, the Y axis on the top is in log10 scale while the Y axis on the bottom is linear. Results are mean ± standard deviation. For Extended Data Fig. 2e,f, 61,179 molecules were randomly picked 30 times from the lead-like make-on-demand library.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Variation of score of top 5000 molecules with library size against the D4 (left), σ2 (middle) and 5HT2A (right) receptor.

The X axis is in log10 scale while the Y axis is linear. The scores of molecules in a singleton scaffold, molecules in a group scaffold, and all top 5000 molecules are shown in orange, blue, and black, respectively. The minimal, 25 percentiles, median, 75 percentiles and maximum of scores are shown on the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th row, respectively. Results are mean ± standard deviation. Each set was selected 30 times with random selection from the full library.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Number of top 5000 molecules in a singleton or group scaffold changes with library size against the D4 (left), σ2 (middle) and 5HT2A (right) receptor.

The X axis is in log10 scale while the Y axis is in linear scale. Results are mean ± standard deviation. Each set was selected 30 times with random selection from the full library.

Supplementary information

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lyu, J., Irwin, J.J. & Shoichet, B.K. Modeling the expansion of virtual screening libraries. Nat Chem Biol 19, 712–718 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-022-01234-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-022-01234-w

This article is cited by

-

Cache: Utilizing ultra-large library screening in Rosetta to identify novel binders of the WD-repeat domain of Leucine-Rich Repeat Kinase 2

Journal of Cheminformatics (2025)

-

InertDB as a generative AI-expanded resource of biologically inactive small molecules from PubChem

Journal of Cheminformatics (2025)

-

Multimodal out-of-distribution individual uncertainty quantification enhances binding affinity prediction for polypharmacology

Nature Machine Intelligence (2025)

-

Ultra-large library screening with an evolutionary algorithm in Rosetta (REvoLd)

Communications Chemistry (2025)

-

The impact of library size and scale of testing on virtual screening

Nature Chemical Biology (2025)