Abstract

Most persons with colorectal cancer (CRC) carry adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) truncation leading to aberrant Wnt–β-catenin signaling; however, effective targeted therapy for them is lacking as the mechanism by which APC truncation drives CRC remains elusive. Here, we report that the cholesterol level in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane (IPM) is elevated in all tested APC-truncated CRC cells, driving Wnt-independent formation of Wnt signalosomes through Dishevelled (Dvl)–cholesterol interaction. Cholesterol–Dvl interaction inhibitors potently blocked β-catenin signaling in APC-truncated CRC cells and suppressed their viability. Because of low IPM cholesterol level and low Dvl expression and dependence, normal cells including primary colon epithelial cells were not sensitive to these inhibitors. In vivo testing with a xenograft mouse model showed that our inhibitors effectively suppressed truncated APC-driven tumors without causing intestinal toxicity. Collectively, these results suggest that the most common type of CRC could be effectively and safely treated by blocking the cholesterol–Dvl–β-catenin signaling axis.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All described data, all the databases/datasets used in the study and accessible links and accession codes are contained within the paper and Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Siegel, R. L., Wagle, N. S., Cercek, A., Smith, R. A. & Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 73, 233–254 (2023).

Kim, M. J., Huang, Y. & Park, J. I. Targeting Wnt signaling for gastrointestinal cancer therapy: present and evolving views. Cancers (Basel) 12, 3638 (2020).

van Neerven, S. M. & Vermeulen, L. The interplay between intrinsic and extrinsic Wnt signaling in controlling intestinal transformation. Differentiation 108, 17–23 (2019).

Nusse, R. & Clevers, H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell 169, 985–999 (2017).

Bugter, J. M., Fenderico, N. & Maurice, M. M. Mutations and mechanisms of WNT pathway tumour suppressors in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 21, 5–21 (2021).

Albrecht, L. V., Tejeda-Muñoz, N. & De Robertis, E. M. Cell biology of canonical Wnt signaling. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 37, 369–389 (2021).

Zhang, L. & Shay, J. W. Multiple roles of APC and its therapeutic implications in colorectal cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 109, djw332 (2017).

Zhang, L. S. & Lum, L. Chemical modulation of WNT signaling in cancer. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 153, 245–269 (2018).

Zhong, Z. & Virshup, D. M. Wnt signaling and drug resistance in cancer. Mol. Pharmacol. 97, 72–89 (2020).

de Sousa, E. M. F. & Vermeulen, L. Wnt signaling in cancer stem cell biology. Cancers (Basel) 8, 60 (2016).

Kahn, M. Wnt signaling in stem cells and cancer stem cells: a tale of two coactivators. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 153, 209–244 (2018).

Steinhart, Z. & Angers, S. Wnt signaling in development and tissue homeostasis. Development 145, dev146589 (2018).

Tan, S. H. & Barker, N. Wnt signaling in adult epithelial stem cells and cancer. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 153, 21–79 (2018).

Kahn, M. Can we safely target the WNT pathway? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13, 513–532 (2014).

Theodoropoulos, P. C. et al. A medicinal chemistry-driven approach identified the sterol isomerase EBP as the molecular target of TASIN colorectal cancer toxins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 6128–6138 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Selective targeting of mutant adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) in colorectal cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 361ra140 (2016).

Erazo-Oliveras, A. et al. Mutant APC reshapes Wnt signaling plasma membrane nanodomains by altering cholesterol levels via oncogenic β-catenin. Nat. Commun. 14, 4342 (2023).

Huang, B., Song, B. L. & Xu, C. Cholesterol metabolism in cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Metab. 2, 132–141 (2020).

Mullen, P. J., Yu, R., Longo, J., Archer, M. C. & Penn, L. Z. The interplay between cell signalling and the mevalonate pathway in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 16, 718–731 (2016).

Juarez, D. & Fruman, D. A. Targeting the mevalonate pathway in cancer. Trends Cancer 7, 525–540 (2021).

Sheng, R. et al. Cholesterol selectively activates canonical Wnt signalling over non-canonical Wnt signalling. Nat. Commun. 5, 4393 (2014).

Liu, S. L. et al. Orthogonal lipid sensors identify transbilayer asymmetry of plasma membrane cholesterol. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13, 268–274 (2017).

Pham, H. et al. Development of a novel spatiotemporal depletion system for cellular cholesterol. J. Lipid Res. 63, 100178 (2022).

Wallingford, J. B. & Habas, R. The developmental biology of Dishevelled: an enigmatic protein governing cell fate and cell polarity. Development 132, 4421–4436 (2005).

Gao, C. & Chen, Y. G. Dishevelled: the hub of Wnt signaling. Cell. Signal. 22, 717–727 (2010).

Schwarz-Romond, T. et al. The DIX domain of Dishevelled confers Wnt signaling by dynamic polymerization. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 484–492 (2007).

Wong, H. C. et al. Direct binding of the PDZ domain of Dishevelled to a conserved internal sequence in the C-terminal region of Frizzled. Mol. Cell 12, 1251–1260 (2003).

Wong, H. C. et al. Structural basis of the recognition of the dishevelled DEP domain in the Wnt signaling pathway. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 1178–1184 (2000).

Francis, K. R. et al. Modeling Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cells reveals a causal role for Wnt/β-catenin defects in neuronal cholesterol synthesis phenotypes. Nat. Med. 22, 388–396 (2016).

Buwaneka, P., Ralko, A., Liu, S. L. & Cho, W. Evaluation of the available cholesterol concentration in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane of mammalian cells. J. Lipid Res. 62, 100084 (2021).

Castellano, B. M. et al. Lysosomal cholesterol activates mTORC1 via an SLC38A9–Niemann–Pick C1 signaling complex. Science 355, 1306–1311 (2017).

Shin, H. R. et al. Lysosomal GPCR-like protein LYCHOS signals cholesterol sufficiency to mTORC1. Science 377, 1290–1298 (2022).

Varma, M. & Deserno, M. Distribution of cholesterol in asymmetric membranes driven by composition and differential stress. Biophys. J. 121, 4001–4018 (2022).

Doktorova, M. et al. Cell membranes sustain phospholipid imbalance via cholesterol asymmetry. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.30.551157 (2023).

Tao, X., Zhao, C. & MacKinnon, R. Membrane protein isolation and structure determination in cell-derived membrane vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2302325120 (2023).

Chandra, S. H., Wacker, I., Appelt, U. K., Behrens, J. & Schneikert, J. A common role for various human truncated adenomatous polyposis coli isoforms in the control of β-catenin activity and cell proliferation. PLoS ONE 7, e34479 (2012).

Ogasawara, F. & Ueda, K. ABCA1 and cholesterol transfer protein Aster-A promote an asymmetric cholesterol distribution in the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 298, 102702 (2022).

McMurray, H. R. et al. Synergistic response to oncogenic mutations defines gene class critical to cancer phenotype. Nature 453, 1112–1116 (2008).

Brown, M. S., Radhakrishnan, A. & Goldstein, J. L. Retrospective on cholesterol homeostasis: the central role of Scap. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 87, 783–807 (2018).

Luo, J., Yang, H. & Song, B. L. Mechanisms and regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 225–245 (2020).

Ahmed, D. et al. Epigenetic and genetic features of 24 colon cancer cell lines. Oncogenesis 2, e71 (2013).

Flanagan, D. J. et al. Frizzled-7 is required for Wnt signaling in gastric tumors with and without APC mutations. Cancer Res. 79, 970–981 (2019).

Saito-Diaz, K. et al. APC inhibits ligand-independent Wnt signaling by the clathrin endocytic pathway. Dev. Cell 44, 566–581(2018).

Schaefer, K. N. & Peifer, M. Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulation and a role for biomolecular condensates. Dev. Cell 48, 429–444 (2019).

Bienz, M. Head-to-tail polymerization in the assembly of biomolecular condensates. Cell 182, 799–811 (2020).

Ohkubo, Y. Z., Pogorelov, T. V., Arcario, M. J., Christensen, G. A. & Tajkhorshid, E. Accelerating membrane insertion of peripheral proteins with a novel membrane mimetic model. Biophys. J. 102, 2130–2139 (2012).

Soubias, O. et al. Membrane surface recognition by the ASAP1 PH domain and consequences for interactions with the small GTPase Arf1. Sci. Adv. 6, eabd1882 (2020).

Singaram, I. et al. Targeting lipid-protein interaction to treat Syk-mediated acute myeloid leukemia. Nat. Chem. Biol. 19, 239–250 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Inhibition of Wnt signaling by Dishevelled PDZ peptides. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 217–219 (2009).

Cho, W. & Stahelin, R. V. Membrane–protein interactions in cell signaling and membrane trafficking. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 34, 119–151 (2005).

Chen, X. & Deng, Y.Simulations of a specific inhibitor of the dishevelled PDZ domain. J. Mol. Model. 15, 91–96 (2009).

Lau, T. et al. A novel tankyrase small-molecule inhibitor suppresses APC mutation-driven colorectal tumor growth. Cancer Res. 73, 3132–3144 (2013).

Liu, J. et al. Targeting Wnt-driven cancer through the inhibition of Porcupine by LGK974. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 20224–20229 (2013).

Dow, L. E. et al. Apc restoration promotes cellular differentiation and reestablishes crypt homeostasis in colorectal cancer. Cell 161, 1539–1552 (2015).

Crespo, M. et al. Colonic organoids derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells for modeling colorectal cancer and drug testing. Nat. Med. 23, 878–884 (2017).

Zhong, Y. et al. Tankyrase inhibition causes reversible intestinal toxicity in mice with a therapeutic index < 1. Toxicol. Pathol. 44, 267–278 (2016).

Voloshanenko, O. et al. Wnt secretion is required to maintain high levels of Wnt activity in colon cancer cells. Nat. Commun. 4, 2610 (2013).

Madan, B. & Virshup, D. M. Targeting Wnts at the source—new mechanisms, new biomarkers, new drugs. Mol. Cancer Ther. 14, 1087–1094 (2015).

Clevers, H., Loh, K. M. & Nusse, R. An integral program for tissue renewal and regeneration: Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Science 346, 1248012 (2014).

Schepers, A. & Clevers, H. Wnt signaling, stem cells, and cancer of the gastrointestinal tract. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a007989 (2012).

Zhang, C. et al. Overexpression of Dishevelled 2 is involved in tumor metastasis and is associated with poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 19, 1507–1517 (2017).

He, T. Y. et al. DDX3 promotes tumor invasion in colorectal cancer via the CK1ε/Dvl2 axis. Sci. Rep. 6, 21483 (2016).

Pulvirenti, T. et al. Dishevelled 2 signaling promotes self-renewal and tumorigenicity in human gliomas. Cancer Res. 71, 7280–7290 (2011).

Metcalfe, C. et al. Dvl2 promotes intestinal length and neoplasia in the ApcMin mouse model for colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 70, 6629–6638 (2010).

Tanaka, N. et al. APC mutations as a potential biomarker for sensitivity to tankyrase inhibitors in colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 16, 752–762 (2017).

Kim, H., Afsari, H. S. & Cho, W. High-throughput fluorescence assay for membrane-protein interaction. J. Lipid Res. 54, 3531–3538 (2013).

Park, M. J. et al. SH2 domains serve as lipid-binding modules for pTyr-signaling proteins. Mol Cell 62, 7–20 (2016).

Buwaneka, P., Ralko, A., Gorai, S., Pham, H. & Cho, W. Phosphoinositide-binding activity of Smad2 is essential for its function in TGF-β signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 297, 101303 (2021).

Ge, S. X., Jung, D. & Yao, R. ShinyGO: a graphical gene-set enrichment tool for animals and plants. Bioinformatics 36, 2628–2629 (2020).

Sharma, A. et al. Photostable and orthogonal solvatochromic fluorophores for simultaneous in situ quantification of multiple cellular signaling molecules. ACS Chem. Biol. 15, 1913–1920 (2020).

Cho, W., Yoon, Y., Liu, S. L., Baek, K. & Sheng, R. Fluorescence-based in situ quantitative imaging for cellular lipids. Methods Enzymol. 583, 19–33 (2017).

Zhang, J. H., Chung, T. D. & Oldenburg, K. R. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J. Biomol. Screen. 4, 67–73 (1999).

Koyama-Honda, I. et al. Fluorescence imaging for monitoring the colocalization of two single molecules in living cells. Biophys. J. 88, 2126–2136 (2005).

Vidana Gamage, H. E. et al. Development of NR0B2 as a therapeutic target for the re-education of tumor associated myeloid cells. Cancer Lett. 597, 217086 (2024).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 27–28 (1996).

Jo, S., Kim, T., Iyer, V. G. & Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: a web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 29, 1859–1865 (2008).

Qi, Y. et al. CHARMM-GUI HMMM builder for membrane simulations with the highly mobile membrane-mimetic model. Biophys. J. 109, 2012–2022 (2015).

Vermaas, J. V., Pogorelov, T. V. & Tajkhorshid, E. Extension of the highly mobile membrane mimetic to transmembrane systems through customized in silico solvents. J. Phys. Chem. B 121, 3764–3776 (2017).

Phillips, J. C. et al. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1781–1802 (2005).

Huang, J. et al. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods 14, 71–73 (2017).

Wells, D. B., Abramkina, V. & Aksimentiev, A. Exploring transmembrane transport through α-hemolysin with grid-steered molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 127, 125101 (2007).

Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455–461 (2010).

Carnevale, L. N., Arango, A. S., Arnold, W. R., Tajkhorshid, E. & Das, A. Endocannabinoid virodhamine Is an endogenous inhibitor of human cardiovascular CYP2J2 epoxygenase. Biochemistry 57, 6489–6499 (2018).

Heyer, L. J., Kruglyak, S. & Yooseph, S. Exploring expression data: identification and analysis of coexpressed genes. Genome Res. 9, 1106–1115 (1999).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R35 GM122530 to W.C.; R01 CA234025 to E.R.N., GM 120281 to V.G.; P41 GM104601 and R01 GM123455 to E.T.; R01 NS114413 to S.M.C.; DK114373 and DK128167 to B.W.) and Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program (Era of Hope Scholar Award BC200206 to E.R.N.). E.T. acknowledges computing resources provided by Blue Waters at National Center for Supercomputing Applications and Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (grant MCA06N060 to E.T.). E.T. is also grateful to the School of Chemical Sciences Scientific Software Program for access to the Schrödinger Suite. W.C. thanks F. Cong of Novartis for a generous gift of Dvl triple-KO MEF cells.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S. performed the inhibitor synthesis, screening and optimization and the cellular assays. J.Z., S.K. and J.S. performed the quantitative imaging analyses. D.G.O., H.S.M. and E.T. performed the computational analysis. A.A. and C.F.D contributed to the inhibitor screening. K.B. and P.B. assisted in the cell studies. K.P., D.A.A., D.P.J., S.M. and S.M.C. performed the MS analyses. Y.W. and V.G. constructed the small-molecule library and participated in the early lead optimization. D.L. assisted in the lead optimization. S.V.B., E.W., R.S., B.W. and E.R.N. performed the in vivo inhibitor testing. W.C. conceptualized and supervised the work and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemical Biology thanks Gunnar Schulte and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Effects of APC and IPM cholesterol on β-catenin stability.

a. Western blot analysis of active β-catenin before and after APC knockdown and site-specific IPM cholesterol depletion, respectively, in APC-truncated CRC (HCT15 and Caco-2) cells. b. Quantification of active β-catenin/GAPDH is shown in a. Error bars are SD’s. n = 3 for all western blots. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA. ns, p > 0.05; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. p = 0.0009 (HCT15; column1-2), 0.0008 (HCT15; column1-3), 0.41 (HCT15; column3-4), 0.00012 (Caco2; column1-2), 0.0037 (Caco2; column1-3), 0.43 (Caco2; column3-4). Displayed gel images are representative of similar images from three independent measurements.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Dvl2 specificity of WC522.

a. The structure of WC522B. b. Western blot analysis of WC522B-binding proteins captured by streptavidin beads pull-down. Biotin was used as a negative control. 1 μM WC522B (12 h) was used for pulldown experiments and GAPDH was used as a gel loading control for all immunoblotting. Displayed data are representative of similar images from three independent measurements.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Inhibition of β-catenin signaling by WC522 and WC593.

a. Inhibition of the active β-catenin level by WC522 and WC593 was measured in unstimulated APC-truncated CRC cells. GAPDH was employed as a gel loading control for all immunoblotting. Displayed gel images are representative of similar images from three independent measurements. b. Quantification of active β-catenin/GAPDH data shown in a. c. Inhibition of β-catenin transcriptional activity by WC522 and WC593 in unstimulated APC-truncated CRC cells measured by the TopFlash luciferase assay. Error bars are SD’s from three independent measurements (n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA. ns, p > 0.05; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. For b, p = 0.021 (HCT15; column1-2), <0.0001 (HCT15; column1-3), <0.0001 (HCT15; column1-4), 0.014 (Caco2; column1-2), <0.0001 (Caco2; column1-3), <0.0001 (Caco2; column1-4), 0.021 (DLD1; column1-2), <0.0001 (DLD1; column1-3), <0.0001 (DLD1; column1-4)., 0.68 (LOVO; column1-2), <0.0001 (LOVO; column1-3), <0.0001 (LOVO; column1-4)., 0.073 (HT29; column1-2), <0.0001 (HT29; column1-3), <0.0001 (HT29; column1-4). For c, p = 0.47 (HCT15; column1-2), <0.0001 (HCT15; column1-3), <0.0001 (HCT15; column1-4), 0.27 (Caco2; column1-2), <0.0001 (Caco2; column1-3), <0.0001 (Caco2; column1-4), 0.26 (DLD1; column1-2), <0.0001 (DLD1; column1-3), <0.0001 (DLD1; column1-4)., 0468 (LOVO; column1-2), <0.0001 (LOVO; column1-3), <0.0001 (LOVO; column1-4)., 0.28 (HT29; column1-2), <0.0001 (HT29; column1-3), <0.0001 (HT29; column1-4).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Cellular inhibitory activity of WC522 and WC593.

a. Inhibition of the active β-catenin level by WC522 and WC593 in Wnt3a-stimulated colon cells. b. Quantification of the data shown in a. c. Inhibition of β-catenin transcriptional activity by WC522 and WC593 in Wnt3a-stimulated colon cells. Wnt3a was 50 ng/ml for HCT15, Caco-2 and DLD1 cells and 200 ng/ml for HCT116, RKO, NCI-H508, and CCD-18Co cells. d. Inhibition of the active β-catenin level by WC522 and WC593 in isogenic HCT15 cells. Western blot analysis of active β-catenin in unstimulated HCT15 cells harboring various APC truncations and FL APC was performed as described in Fig. 3a. e. Quantification of the data shown in d. 1 μM WC522 and WC593 (12 h) were used for all inhibition experiments. GAPDH was employed as a gel loading control for all immunoblotting. Error bars are SD’s. n = 3 for all measurements. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA. ns, p > 0.05; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. For b, p = 0.00025 (HCT15; column1-2), 0.45 (HCT15; column2-3), <0.0001 (HCT15; column2-4), <0.0001 (HCT15; column2-5), 0.0096 (Caco2; column1-2), 0.34 (Caco2; column2-3), <0.0001 (Caco2; column2-4), <0.0001 (Caco2; column2-5), <0.0001 (DLD1; column1-2), 0.048 (DLD1; column2-3), <0.0001 (DLD1; column2-4), <0.0001 (DLD1; column2-5), 0.0009 (HCT116; column1-2), 0.86 (HCT116; column2-3), 0.039 (HCT116; column2-4), 0.0045 (HCT116; column2-5), 0.004 (RKO; column1-2), 0.79 (RKO; column2-3), 0.51 (RKO; column2-4), 0.086 (RKO; column2-5), 0.002 (NCI-H508; column1-2), 0.57 (NCI-H508; column2-3), 0.33 (NCI-H508; column2-4), 0.14 (NCI-H508; column2-5), <0.0001 (CCD-18Co; column1-2), 0.075 (CCD-18Co; column2-3), 0.037 (CCD-18Co; column2-4), 0.012 (CCD-18Co; column2-5). For c, p = <0.0001 (HCT15; column1-2), 0.43 (HCT15; column2-3), <0.0001 (HCT15; column2-4), <0.0001 (HCT15; column2-5), <0.0001 (Caco2; column1-2), 0.56 (Caco2; column2-3), <0.0001 (Caco2; column2-4), <0.0001 (Caco2; column2-5), <0.0001 (DLD1; column1-2), 0.23 (DLD1; column2-3), <0.0001 (DLD1; column2-4), <0.0001 (DLD1; column2-5), 0.0002 (CCD-18Co; column1-2), 0.27(CCD-18Co; column2-3), 0.066 (CCD-18Co; column2-4), 0.019 (CCD-18Co; column2-5). For e, p = <0.0001 (APC1-1941; column1-2), <0.0001 (APC1-1941; column1-3), <0.0001 (APC1-1941; column1-4), 0.11 (APC1-1309; column1-2), <0.0001 (APC1-1309; column1-3), <0.0001 (APC1-1309; column1-4), 0.68 (APC1-331; column1-2), <0.0001 (APC1-331; column1-3), <0.0001 (APC1-331; column1-4), 0.55 (APC1-2843; column1-2), 0.31 (APC1-2843; column1-3), 0.16 (APC1-2843; column1-4).

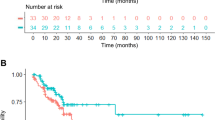

Extended Data Fig. 5 In vivo safety of WC522 and WC593.

a. The length of intestines in xenografted mice treated with placebo, WC593, and WC522 for 21 days. b. Representative histology and quantification of jejunum from mice as in a (~40 villi and 40 crypts per mouse, 6–9 mice/group). c. Representative images of EdU staining and quantification of EdU+ proliferating cells in mice (~25 crypts per mouse, 6–9 mice/group). Scale bars indicate 200 µm for b and 50 µm for c, respectively. For all data, values are means ± SEM with n = 10 for each group. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA. ns, p > 0.05; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. For a, p = 0.79 (column1-2), 0.79 (column1-3). For b, p = 0.46 (villi; column1-2), 0.43 (villi; column1-3), 0.60 (crypt height; column1-2), 0.13 (crypt height; column1-3), 0.11 (crypt number; column1-2), 0.22 (crypt number; column1-3). For c, p = 0.29 (column1-2), 0.07 (column1-3).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–16, Tables 1–3, Notes 1 and 2 and Data 1–6.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sharma, A., Zalejski, J., Bendre, S.V. et al. Cholesterol-targeting Wnt–β-catenin signaling inhibitors for colorectal cancer. Nat Chem Biol 21, 1376–1386 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-01870-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-01870-y

This article is cited by

-

Boosting immunotherapy by restoring cryptic APC function

Cell Research (2026)

-

Targeting PTPN13 with 11-amino-acid peptides of C-terminal APC prevents immune evasion of colorectal cancer

Cell Research (2026)

-

Single-cell sequencing and organoids: applications in organ development and disease

Molecular Biomedicine (2025)

-

Trimming the fat from Dishevelled

Nature Chemical Biology (2025)