Abstract

Reprogramming the specificity of proteases toward alternative target sequences could enable an array of exciting applications, ranging from proteome editing to therapeutic interventions. Here we report an in vivo life–death selection system for protease reprogramming using the toxic N-terminal domain of gasdermin D (GD-N) protein as a selection marker. The approach is a modular system that can be used to cover the protease mutational diversity in the billions through only a few cycles of directed evolution. By inserting the desired cleavage sequence into the loop region of the GD-N protein, which is toxic to host bacteria cells, the system selects for efficient substrate cleavage—rendering GD-N nontoxic—by enrichment of bacteria in liquid culture. Using the tobacco etch virus protease (TEVp) and corresponding substrate sequence as a model, we demonstrated that our platform could select and enrich an efficient protease variant millionfold after a single round of selection. We also evolve TEVp to cut sequences on target proteins with known pathological roles.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data are available in the main article and Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Fink, T. & Jerala, R. Designed protease-based signaling networks. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 68, 102146 (2022).

Pessela, B. C., Noma Okamoto, D. & Cabral, H. Editorial: Microbial proteases: biochemical studies, immobilization and biotechnological application. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1126989 (2023).

Yuan, J. & Ofengeim, D. A guide to cell death pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 379–395 (2024).

Yong, J. & Toh, C. H. Rethinking coagulation: from enzymatic cascade and cell-based reactions to a convergent model involving innate immune activation. Blood 142, 2133–2145 (2023).

Broz, P., Pelegrin, P. & Shao, F. The gasdermins, a protein family executing cell death and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 143–157 (2020).

Komor, A. C., Badran, A. H. & Liu, D. R. CRISPR-based technologies for the manipulation of eukaryotic genomes. Cell 168, 20–36 (2017).

Doman, J. L. et al. Phage-assisted evolution and protein engineering yield compact, efficient prime editors. Cell 186, 3983–4002 (2023).

Packer, M. S., Rees, H. A. & Liu, D. R. Phage-assisted continuous evolution of proteases with altered substrate specificity. Nat. Commun. 8, 956 (2017).

Blum, T. R. et al. Phage-assisted evolution of botulinum neurotoxin proteases with reprogrammed specificity. Science 371, 803–810 (2021).

Wasunan, P., Maneewong, C., Daengprok, W. & Thirabunyanon, M. Bioactive earthworm peptides produced by novel protease-producing Bacillus velezensis PM 35 and its bioactivities on liver cancer cell death via apoptosis, antioxidant activity, protection against oxidative stress, and immune cell activation. Front. Microbiol. 13, 892945 (2022).

Sanchez, M. I. & Ting, A. Y. Directed evolution improves the catalytic efficiency of TEV protease. Nat. Methods 17, 167–174 (2020).

Pedram, K. et al. Design of a mucin-selective protease for targeted degradation of cancer-associated mucins. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 597–607 (2024).

Wardman, J. F. et al. A high-throughput screening platform for enzymes active on mucin-type O-glycoproteins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 19, 1246–1255 (2023).

Nathans, D. & Smith, H. O. Restriction endonucleases in the analysis and restructuring of DNA molecules. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 44, 273–293 (1975).

Bandeira, N. Revealing deep proteome diversity with community-scale proteomics big data. In Proc. 8th International Conference on Computational Systems-Biology and Bioinformatics (eds Binh, H. T. T. & Tongsima, S.) (ACM, 2017).

Yi, L. et al. Engineering of TEV protease variants by yeast ER sequestration screening (YESS) of combinatorial libraries. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 7229–7234 (2013).

Denard, C. A. et al. YESS 2.0, a tunable platform for enzyme evolution, yields highly active TEV protease variants. ACS Synth. Biol. 10, 63–71 (2021).

Liu, Z., Chen, S. & Wu, J. Advances in ultrahigh-throughput screening technologies for protein evolution. Trends Biotechnol. 41, 1168–1181 (2023).

Esvelt, K. M., Carlson, J. C. & Liu, D. R. A system for the continuous directed evolution of biomolecules. Nature 472, 499–503 (2011).

Liu, X. et al. Inflammasome-activated gasdermin D causes pyroptosis by forming membrane pores. Nature 535, 153–158 (2016).

Kuang, S. et al. Structure insight of GSDMD reveals the basis of GSDMD autoinhibition in cell pyroptosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 10642–10647 (2017).

Xia, S. et al. Gasdermin D pore structure reveals preferential release of mature interleukin-1. Nature 593, 607–611 (2021).

He, L. et al. Optogenetic control of non-apoptotic cell death. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.) 8, 2100424 (2021).

Johnson, A. G. et al. Bacterial gasdermins reveal an ancient mechanism of cell death. Science 375, 221–225 (2022).

Johnson, A. G. et al. Structure and assembly of a bacterial gasdermin pore. Nature 628, 657–663 (2024).

Kambara, H. et al. Gasdermin D exerts anti-inflammatory effects by promoting neutrophil death. Cell Rep. 22, 2924–2936 (2018).

Cesaratto, F., Burrone, O. R. & Petris, G. Tobacco etch virus protease: a shortcut across biotechnologies. J. Biotechnol. 231, 239–249 (2016).

Phan, J. et al. Structural basis for the substrate specificity of tobacco etch virus protease. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 50564–50572 (2002).

Sun, P., Austin, B. P., Tozser, J. & Waugh, D. S. Structural determinants of tobacco vein mottling virus protease substrate specificity. Protein Sci. 19, 2240–2251 (2010).

Clark, E. A. & Giltiay, N. V. CD22: a regulator of innate and adaptive B cell responses and autoimmunity. Front. Immunol. 9, 2235 (2018).

Ramakrishna, S. et al. Modulation of CD22 antigen density improves efficacy of CD22 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells against CD22lo B-lineage leukemia and lymphoma. Blood 130, 3894 (2017).

Ereno-Orbea, J. et al. Molecular basis of human CD22 function and therapeutic targeting. Nat. Commun. 8, 764 (2017).

Yu, S.-F. et al. An anti-CD22-seco-CBI-dimer antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) for the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that provides a longer duration of response than auristatin-based ADCs in preclinical models. Mol. Cancer Ther. 20, 340–346 (2021).

Xu, J., Luo, W., Li, C. & Mei, H. Targeting CD22 for B-cell hematologic malignancies. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 12, 90 (2023).

Ereno-Orbea, J. et al. Structural details of monoclonal antibody m971 recognition of the membrane-proximal domain of CD22. J. Biol. Chem. 297, 100966 (2021).

Abe, K. et al. Doxorubicin causes ferroptosis and cardiotoxicity by intercalating into mitochondrial DNA and disrupting ALAS1-dependent heme synthesis. Sci. Signal. 15, eabn8017 (2022).

Yasuda, M. et al. RNAi-mediated silencing of hepatic ALAS1 effectively prevents and treats the induced acute attacks in acute intermittent porphyria mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 7777–7782 (2014).

Yasuda, M., Keel, S. & Balwani, M. RNA interference therapy in acute hepatic porphyrias. Blood 142, 1589–1599 (2023).

Lee, S., Lee, S., Desnick, R., Yasuda, M. & Lai, E. C. Noncanonical role of ALAS1 as a heme-independent inhibitor of small RNA-mediated silencing. Science 386, 1427–1434 (2024).

Kang, Y. C. et al. Cell-penetrating artificial mitochondria-targeting peptide-conjugated metallothionein 1A alleviates mitochondrial damage in Parkinson’s disease models. Exp. Mol. Med 50, 1–13 (2018).

Xiao, Q. et al. Engineered cell-penetrating peptides for mitochondrion-targeted drug delivery in cancer therapy. Chemistry 27, 14721–14729 (2021).

Jenseit, A., Camgoz, A., Pfister, S. M. & Kool, M. EZHIP: a new piece of the puzzle towards understanding pediatric posterior fossa ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol. 143, 1–13 (2022).

Jain, S. U. et al. H3 K27M and EZHIP impede H3K27-methylation spreading by inhibiting allosterically stimulated PRC2. Mol. Cell 80, 726–735 e727 (2020).

Jain, S. U. et al. PFA ependymoma-associated protein EZHIP inhibits PRC2 activity through a H3 K27M-like mechanism. Nat. Commun. 10, 2146 (2019).

Panwalkar, P. et al. Targeting integrated epigenetic and metabolic pathways in lethal childhood PFA ependymomas. Sci. Transl. Med. 13, eabc0497 (2021).

Akishiba, M. et al. Cytosolic antibody delivery by lipid-sensitive endosomolytic peptide. Nat. Chem. 9, 751–761 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. Dose-dependent nuclear delivery and transcriptional repression with a cell-penetrant MeCP2. ACS Cent. Sci. 9, 277–288 (2023).

Knox, S. L., Wissner, R., Piszkiewicz, S. & Schepartz, A. Cytosolic delivery of argininosuccinate synthetase using a cell-permeant miniature protein. ACS Cent. Sci. 7, 641–649 (2021).

Li, W. et al. A siRNA-induced peptide co-assembly system as a peptide-based siRNA nanocarrier for cancer therapy. Mater. Horiz. 5, 745–752 (2018).

Guidotti, G., Brambilla, L. & Rossi, D. Cell-penetrating peptides: from basic research to clinics. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 38, 406–424 (2017).

Hie, B. L. et al. Efficient evolution of human antibodies from general protein language models. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 275–283 (2024).

Kille, S. et al. Reducing codon redundancy and screening effort of combinatorial protein libraries created by saturation mutagenesis. ACS Synth. Biol. 2, 83–92 (2013).

Philip, J. et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236–1240 (2014).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 25, 25–29 (2000).

Minoru, K., Susumu, G., Yoko, S., Miho, F. & Mao, T. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D109–D114 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank the support from ChomiX Biotech for the proteomics analysis. This work was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (22077059, 22277048, 22477053 and 92253304 to J.W.; 21937001, 22137001 and 91753000 to P.R.C.), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA1302603 and 2023YFA1506500 to P.R.C.; 2021YFA0910800 and 2023YFA1506500 to J.W.), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Z200010 to P.R.C.), New Cornerstone Science Foundation through the New Cornerstone Investigator Program (to P.R.C.), Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program from China Association for Science and Technology (YESS20200010 to J.W.), Shenzhen Innovation of Science and Technology Commission Grant (JCYJ20210324104210028, RCYX20210609103118010 and QTD20221101093558015 to J.W.) and Shenzhen Medical Research Funding (A2303067 to J.W.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.R.C. and J.W. designed the research and wrote the paper with input from all authors. Z.G., T.L., H.Y., W.S.C.N. and H.W. conducted most of the experiments.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemical Biology thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this workss.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Expression and function of the GSDMD-N protein in E. coli.

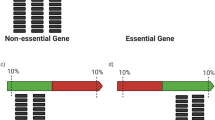

a, Schematic mechanism of the protease reprogramming process utilizing the Gasdermin D-based selection system. A specific sequence for recognition was incorporated into a flexible loop of a toxic protein (GSDMD-N, GD-N) to establish an in vivo selection system. If a protease variant successfully cleaves the targeted sequence, GD-N becomes non-toxic, allowing the host to survive. If not, GD-N could be assembled into a pore structure on bacteria membrane, leading to the death of the host bacteria. This system coupled the protease activity and cell growth with high fidelity and robustness, which can be further utilized to evolve the activity and specificity of the desired protease. b, c, Expression of the GD-N protein in E. coli. d, Expression of the SUMO-GD-N protein in E. coli. d reproduced the data shown in Fig. 1e and was included here to facilitate direct comparison with coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) stain result. e, Location of expressed GD-N-GFP in E. coli. The cell wall of E. coli was first labeled with HADA for 4 hours, after which GD-N-GFP was expressed for 6 hours. The GD-N-GFP accumulated on the membrane, but the membrane structure had not yet to be destroyed. f, Membrane staining of E. coli after the expression of SUMO-GSDMD-N for 24 h. The membrane of E. coli was stained with FITC for 1 h. Schematic diagrams were created with BioRender.com.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Screening of optimal selection plasmid.

a, Crystal structure showed the insertion positions of the target sequences on SUMO-GD-N protein (PDB: 6VFE), and the different insertion positions would determine whether this modified SUMO-GD-N version met the requirements (as showed in the schematic diagram). b, The detailed amino acid sequence information of various SUMO-GD-N versions (P1-P15). c, The toxic effect of different SUMO-GD-N versions (P1-P15) in E. coli. The SUMO-GD-N (Dead mutant) version which hardly affects bacterial growth was used as a positive reference, and the wild-type SUMO-GD-N which strongly suppressed bacterial growth was used as a negative reference. This experiment was performed three times. Schematic diagrams were created with BioRender.com.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Validation of the optimal reprogramming system.

a, Western blot detected the expression of different versions of SUMO-GD-N. b, Schematic diagram of the in vivo selection process. c, Proportion of TEVp-WT / TEVp-C151A genotype before and after the in vivo selection process. d, Proportion of P10 / GD-N-WT genotype before and after the in vivo selection process. Schematic diagrams were created with BioRender.com.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Design and functional evaluation of the negative selection system for protease evolution.

a, Predicted structure of GSDMD protein (AF-P57764-F1). b, The detailed amino acid sequence information of various GD-F versions (N1-N9). c, Schematic diagram of negative selection system. d, Evaluation of the N1-N9 variants to identify suitable SUMO-GSDMD variants for further applications. The x-axis was the OD600 ratio between bacteria without the SUMO-GSDMD protein and bacteria expressing SUMO-GSDMD, representing the toxicity of each SUMO-GSDMD variant; the y-axis was the OD600 ratio between bacteria without TEV expression and bacteria expressing the TEV protease, representing the ability of TEV protease to cleave the ENLYFQS sequence and to suppress bacterial growth. Schematic diagrams were created with BioRender.com.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Evolution of the TEV protease for the target cleavage of CD22 protein.

a, Enriched mutation pattern of TEV protease after the 1st, 2nd and 3rd rounds of selection at different mutation sites. Pie charts indicated the proportion of different TEV variants in selection progress. b, Comparison of evolved TEV variants in 3 rounds selection progress for the cleavage of the target sequence.

Extended Data Fig. 6 The complexity of mutant-libraries and the transformation efficiency in the individual selection rounds.

a, the transformation efficiency of the competent cells used for constructing the mutant library in this work (with the standard plasmid pUC19) and the chromatograms of the mutated sites. b, The WebLogo representing amino acid diversity was generated using an online tool (https://weblogo.threeplusone.com/). For further analysis, the 4M1 library was selected for next-generation sequencing (NGS). c, the transformation efficiency achieved in each individual selection.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Schematic diagram showed the evolutionary pathway of selection progress.

Lists showed the sequence information of variants in CD22-1st, -2nd and -3rd round selection progresses.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Evolution of the TEV protease for the target cleavage of ALAS1 proteins.

a, Structure and mutation sites of the TEV protease in the round-1 evolution of TEVp (PDB: 1LVM). b, Pie chart indicated the proportion of different TEV variants in ALAS1-1st round selection progress. c, Enriched mutation pattern of TEVp after the first round of selection. d, Structure and mutation sites of the TEV protease in the round-2 evolution of TEVp (PDB: 1LVM). e, Pie chart indicated the proportion of different TEV variants in ALAS1-2nd round selection progress. f, Enriched mutation pattern of TEVp after the second round of selection. g, Comparison of evolved TEV variants in ALAS1-1st round selection progress for the cleavage of the target sequence. The MBP-HNIYVQA-GFP was utilized as the substrate, and TEVp-WT was used as the control. h, The cleavage kinetics of TEVALAS1-2.1 to MBP-HNIYVQA-GFP. i, Cleavage rate of MBP-HNIYVQA-GFP by different concentration of TEVALAS1-2.1. The concentration of MBP-HNIYVQA-GFP is 25 mM. j-k, Based on this evolution system, sequence tolerance at each position of the recognition motif was systematically evaluated for both TEVp-WT and TEVALAS1-2.1. By randomizing each site of the substrate and then conducting the selection process, the information of sequence tolerance at each site was obtained. The substrate recognition patterns differed substantially between the wild-type and evolved variants, indicating that the specificity of TEVp was reprogramed rather than evolved to be more promiscuous.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Schematic diagram showed the evolutionary pathway of selection progress.

Lists showed the sequence information of variants in ALAS1-1st and -2nd round selection progress.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Evolution of the TEV protease for target cleavage of EZHIP proteins and Cell-penetrating peptide screening.

a, The sequence information of variants in EZHIP-selection progress. b, Comparison of cutting efficiency TEVp-WT for the target sequence and intermediate sequence by using MBP-EXLXFQS-GFP as the substrate. c, Pie chart indicated the proportion of different TEV variants in EZHIP-selection progress. d, Comparison of cutting efficiency of evolved TEVp hits for the MBP-ERLAFQS-GFP substrate. e. The cleavage kinetics of TEVALAS1-2.1 to MBP-ERLAFQS-GFP. f. Based on this evolution system, sequence tolerance at each position of the recognition motif was systematically evaluated for TEVEZHIP-1.1. g, Schematic diagram of cell-penetrating peptide delivering TEVEZHIP-1.1 into cytoplasm. h, L17E mixed with different concentration of TEVEZHIP-1.1, then HEK-293T cells transfected with EZHIP were treated with the mixture. i, WPC mixed with different concentration of TEVEZHIP-1.1, then HEK-293T cells transfected with EZHIP were treated with the mixture. j, HEK-293T cells transfected with EZHIP were treated with different concentration of TEVEZHIP-1.1-R5 (TEVEZHIP-1.1 fused with 5 Arg). Using western blot to detect the cleavage of variant on EZHIP. This experiment was performed three times with similar results. Schematic diagrams were created with BioRender.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–5.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Unprocessed western blots and gels.

Source Data Fig. 5

Unprocessed western blots and gels.

Source Data Figs. 5, 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Unprocessed western blots and gels.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Unprocessed western blots and gels.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Unprocessed gels

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Unprocessed gels

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Unprocessed western blots and gels.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Z., Li, T., Ye, H. et al. A gasdermin-based life–death evolution system for reprogramming protease specificity. Nat Chem Biol 22, 87–96 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-02063-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-02063-3