Abstract

Nitrogenase catalyzes atmospheric nitrogen fixation, a critical biological process that depends on an intricate organometallic cofactor assembled by a dedicated multiprotein system. Here we uncover the structural basis for the function of NifEN, the scaffold protein that mediates the final stages of cofactor biosynthesis before its incorporation into nitrogenase. High-resolution structural analyses reveal that the cofactor precursor initially binds at a surface docking site before being transferred into a specialized cavity for further maturation. This process involves dynamic structural rearrangements, including coordinated domain motions and partial unfolding, enabling the scaffold to alternate between open and closed states. Additionally, a rear channel extends to the precursor-binding cavity, likely facilitating the entry of the modifying components molybdenum and homocitrate. These findings illuminate the dynamic mechanisms underlying FeMo-cofactor assembly and underscore the functional divergence between NifEN, the biosynthetic scaffold, and NifDK, the catalytic component of nitrogenase.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The coordinates were deposited to the PDB under accession numbers 9I0F, 9I0G and 9I0H, corresponding to reinvestigated AvNifEN, holo-GmNifEN and transit-GmNifEN, respectively. The corresponding cryoEM volume reconstructions were deposited to the EM Data Bank under accession numbers EMD-52557 and EMD-52558 (holo-GmNifEN and transit-GmNifEN, respectively). Data are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Hoffman, B. M., Lukoyanov, D., Yang, Z.-Y., Dean, D. R. & Seefeldt, L. C. Mechanism of nitrogen fixation by nitrogenase: the next stage. Chem. Rev. 114, 4041–4062 (2014).

Burén, S., Jiménez-Vicente, E., Echavarri-Erasun, C. & Rubio, L. M. Biosynthesis of nitrogenase cofactors. Chem. Rev. 120, 4921–4968 (2020).

Schindelin, H., Kisker, C., Schlessman, J. L., Howard, J. B. & Rees, D. C. Structure of ADP·AIF4−-stabilized nitrogenase complex and its implications for signal transduction. Nature 387, 370–376 (1997).

Spatzal, T. et al. Evidence for interstitial carbon in nitrogenase FeMo cofactor. Science 334, 940 (2011).

Seefeldt, L. C. et al. Reduction of substrates by nitrogenases. Chem. Rev. 120, 5082–5106 (2020).

Corbett, M. C. et al. Comparison of iron–molybdenum cofactor-deficient nitrogenase MoFe proteins by X-ray absorption spectroscopy: implications for P-cluster biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 28276–28282 (2004).

van Stappen, C. et al. A conformational role for NifW in the maturation of molybdenum nitrogenase P-cluster. Chem. Sci. 13, 3489–3500 (2022).

Allen, R. M., Chatterjee, R., Ludden, P. W. & Shah, V. K. Incorporation of iron and sulfur from NifB cofactor into the iron–molybdenum cofactor of dinitrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 26890–26896 (1995).

Hu, Y. et al. FeMo cofactor maturation on NifEN. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 17119–17124 (2006).

Curatti, L. et al. In vitro synthesis of the iron–molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase from iron, sulfur, molybdenum, and homocitrate using purified proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 17626–17631 (2007).

Soboh, B., Igarashi, R. Y., Hernandez, J. A. & Rubio, L. M. Purification of a NifEN protein complex that contains bound molybdenum and a FeMo-co precursor from an Azotobacter vinelandii ΔnifHDK strain. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 36701–36709 (2006).

Schmid, B. et al. Structure of a cofactor-deficient nitrogenase MoFe protein. Science 296, 352–356 (2002).

Fani, R., Gallo, R. & Liò, P. Molecular evolution of nitrogen fixation: the evolutionary history of the nifD, nifK, nifE, and nifN genes. J. Mol. Evol. 51, 1–11 (2000).

Einsle, O. & Rees, D. C. Structural enzymology of nitrogenase enzymes. Chem. Rev. 120, 4969–5004 (2020).

Kaiser, J. T., Hu, Y., Wiig, J. A., Rees, D. C. & Ribbe, M. W. Structure of precursor-bound NifEN: a nitrogenase FeMo cofactor maturase/insertase. Science 331, 91–94 (2011).

Kleywegt, G. J. et al. The Uppsala Electron-Density Server. Acta Crystallogr. D 60, 2240–2249 (2004).

Joosten, R. P., Long, F., Murshudov, G. N. & Perrakis, A. The PDB_REDO server for macromolecular structure model optimization. IUCrJ 1, 213–220 (2014).

van Beusekom, B. et al. Homology-based hydrogen bond information improves crystallographic structures in the PDB. Protein Sci. 27, 798–808 (2018).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Rubio, L. M., Singer, S. W. & Ludden, P. W. Purification and characterization of NafY (apodinitrogenase γ subunit) from Azotobacter vinelandii. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 19739–19746 (2004).

Phillips, A. H. et al. Environment and coordination of FeMo-co in the nitrogenase metallochaperone NafY. RSC Chem. Biol. 2, 1462–1465 (2021).

Sippel, D. & Einsle, O. The structure of vanadium nitrogenase reveals an unusual bridging ligand. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13, 956–960 (2017).

Trncik, C., Detemple, F. & Einsle, O. Iron-only Fe-nitrogenase underscores common catalytic principles in biological nitrogen fixation. Nat. Catal. 6, 415–424 (2023).

Wiig, J. A., Hu, Y. & Ribbe, M. W. NifEN–B complex of Azotobacter vinelandii is fully functional in nitrogenase FeMo cofactor assembly. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 8623–8627 (2011).

Yoshizawa, J. M., Fay, A. W., Lee, C. C., Hu, Y. & Ribbe, M. W. Insertion of heterometals into the NifEN-associated iron–molybdenum cofactor precursor. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 15, 421–428 (2010).

Hernandez, J. A. et al. Metal trafficking for nitrogen fixation: NifQ donates molybdenum to NifEN/NifH for the biosynthesis of the nitrogenase FeMo-cofactor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 11679–11684 (2008).

George, S. J., Hernandez, J. A., Jimenez-Vicente, E., Echavarri-Erasun, C. & Rubio, L. M. EXAFS reveals two Mo environments in the nitrogenase iron–molybdenum cofactor biosynthetic protein NifQ. Chem. Commun. 52, 11811–11814 (2016).

Baussier, C. et al. Making iron–sulfur cluster: structure, regulation and evolution of the bacterial ISC system. Adv. Micro. Physiol. 76, 1–39 (2020).

Lill, R. From the discovery to molecular understanding of cellular iron–sulfur protein biogenesis. Biol. Chem. 401, 855–876 (2020).

Markley, J. L. et al. Metamorphic protein IscU alternates conformations in the course of its role as the scaffold protein for iron–sulfur cluster biosynthesis and delivery. FEBS Lett. 587, 1172–1179 (2013).

Bothe, J. R. et al. The complex energy landscape of the protein IscU. Biophys. J. 109, 1019–1025 (2015).

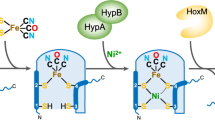

Caserta, G. et al. Stepwise assembly of the active site of [NiFe]-hydrogenase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 19, 498–506 (2023).

Lampret, O. et al. The final steps of [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 15802–15810 (2019).

Namkoong, G. & Suess, D. L. M. Cluster-selective 57Fe labeling of a Twitch-domain-containing radical SAM enzyme. Chem. Sci. 14, 7492–7499 (2023).

Lago-Maciel, A. et al. Methylthio-alkane reductases use nitrogenase metalloclusters for carbon–sulfur bond cleavage. Nat. Catal 8, 1086–1099 (2025).

Payá-Tormo, L. et al. Iron–molybdenum cofactor synthesis by a thermophilic nitrogenase devoid of the scaffold NifEN. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2406198121 (2024).

Dobrzyńska, K. et al. Nitrogenase cofactor biosynthesis using proteins produced in mitochondria of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. mBio 15, e0308823 (2024).

Koskela, E. V. & Frey, A. D. Homologous recombinatorial cloning without the creation of single-stranded ends: exonuclease and ligation-independent cloning (ELIC). Mol. Biotechnol. 57, 233–240 (2015).

Fajardo, A. S. et al. Structural insights into the mechanism of the radical SAM carbide synthase NifB, a key nitrogenase cofactor maturating enzyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 11006–11012 (2020).

Guo, Y. et al. The nitrogenase FeMo-cofactor precursor formed by NifB protein: a diamagnetic cluster containing eight iron atoms. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 12764–12767 (2016).

Payá-Tormo, L. et al. A colorimetric method to measure in vitro nitrogenase functionality for engineering nitrogen fixation. Sci. Rep. 12, 10367 (2022).

Dos Santos, P. C. Molecular biology and genetic engineering in nitrogen fixation. Methods Mol. Biol. 766, 81–92 (2011).

Cherrier, M. V. et al. Oxygen-sensitive metalloprotein structure determination by cryo-electron microscopy. Biomolecules 12, 441 (2022).

Schorb, M., Haberbosch, I., Hagen, W. J. H., Schwab, Y. & Mastronarde, D. N. Software tools for automated transmission electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 16, 471–477 (2019).

Punjani, A., Rubinstein, J. L., Fleet, D. J. & Brubaker, M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017).

Evans, R. et al. Protein complex prediction with AlphaFold-Multimer. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.04.463034 (2022).

He, J., Li, T. & Huang, S.-Y. Improvement of cryo-EM maps by simultaneous local and non-local deep learning. Nat. Commun. 14, 3217 (2023).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 486–501 (2010).

Liebschner, D. et al. Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in PHENIX. Acta Crystallogr. D 75, 861–877 (2019).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF ChimeraX: structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 30, 70–82 (2021).

Steinkellner, G., Rader, R., Thallinger, G. G., Kratky, C. & Gruber, K. VASCo: computation and visualization of annotated protein surface contacts. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 32 (2009).

Hendlich, M., Rippmann, F. & Barnickel, G. LIGSITE: automatic and efficient detection of potential small molecule-binding sites in proteins. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 15, 359–363 (1997).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 421 (2009).

Sievers, F. & Higgins, D. G. The Clustal Omega multiple alignment package. In Multiple Sequence Alignment: Methods and Protocols (ed. Katoh, K.) 3–16 (Springer, 2021).

Madeira, F. et al. The EMBL-EBI job dispatcher sequence analysis tools framework in 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W521–W525 (2024).

Crooks, G. E., Hon, G., Chandonia, J.-M. & Brenner, S. E. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190 (2004).

Mirdita, M. et al. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 19, 679–682 (2022).

Winn, M. D. et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D 67, 235–242 (2011).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 213–221 (2010).

Murshudov, G. N. Some properties of crystallographic reliability index—Rfactor: effects of twinning. Appl. Comput. Math. 10, 250–261 (2011).

Acknowledgements

C.F. is grateful to I. Polsinelli for fruitful discussions and valuable advice to improve the revisiting of the NifEN crystal structure. T.-Q.N. acknowledges A. Usclat for his help with GmNifEN variants expression and purification. Y.N., M.V.C. and G.S. thank the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, notably E. Kandiah from the CM01 microscope facility, for their help in cryoEM data acquisition. A. vinelandii strain DJ2925 was generated in the D. Dean laboratory at Virginia Tech. This work was supported by the French National Research Agency in the framework of the Investissements d’Avenir program (ANR-15-IDEX-02) through the funding of the ‘Origin of Life’ project of the Université Grenoble Alpes. This work was also supported by grant PID2021-128802OB-100 funded by MICIU/AEI/s1910.13039/501100011033 and by European Regional Development Fund/European Union. This work used the platforms of the Grenoble Instruct-ERIC center (ISBG; UAR 3518 CNRS-CEA-UGA-EMBL) within the Grenoble Partnership for Structural Biology, which is supported by FRISBI (ANR-10-INBS-05-02) and GRAL and financed within the Université Grenoble Alpes graduate school (Ecoles Universitaires de Recherche) CBH-EUR-GS (ANR-17-EURE-0003). The EM facility is supported by the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes Region, the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, Fond Européen de Développement Régional and the GIS Infrastructures en Biologie Santé et Agronomie. T.-Q.N. was supported by the Contrat de Formation par la Recherche program from the Commissariat à l’Énergie Atomique et aux Énergies Alternatives and by the GRAL Grenoble Alliance for Integrated Structural and Cell Biology program through its PhD operating costs action (ANR-17-EURE-0003). G.C. was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) through the cluster of excellence ‘UniSysCat’ under the Excellence Strategy (EXC2008-390540038). K.D. was a recipient of an Formación Personal Investigador predoctoral fellowship from Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (PRE2018-084951). L.P.T. and H.B. were recipients of Margarita Salas and María Zambrano contracts, funded by Ministerio de Universidades and NextGeneration EU (RD 289/2021), respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.V.C., L.M.R. and Y.N. conceptualized the study. M.V.C. and Y.N. designed the structural biology experiments. L.P.T., T.-Q.N. and L.M. expressed and purified the protein samples. L.P.T., M.V.C. and Y.N. prepared the cryoEM grids. L.P.T., M.V.C. and G.S. collected and processed the cryoEM images. L.P.T. and M.V.C. analyzed the cryoEM images and reconstructed the models. C.F., G.C., P.L., A.T. and M.V.C. refined the crystal structure. P.A. performed the bioinformatic analyses. H.B., K.D. and C.E.-E. performed the in vitro activity assays. Y.N. performed the structural analyses and wrote the initial draft. M.V.C. and P.A. prepared the figures. L.M.R. and Y.N. edited the manuscript with contributions from all coauthors. M.V.C., L.M.R. and Y.N. supervised the work. L.M.R. and Y.N. provided resources.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemical Biology thanks Wonchull Kang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Comparisons of the AvNifDK and AvNifEN crystal structures.

a, Cartoon representation of the A. vinelandii Mo-nitrogenase (PDB ID: 4WZB). The NifH, NifD and NifK subunits are depicted in blue, yellow and salmon ribbons, respectively. One half of the αβγ2 quaternary structure is depicted in solid colors. ATP is depicted in sticks whereas NifH [Fe4S4]-cluster, NifDK P-cluster and FeMo-co are in ball-and-sticks, with C, N, O, Fe, Mo and S atoms depicted in gray, blue, red, brown, green and yellow, respectively. b, Ribbon cartoon representation of the structure of the scaffold protein from A. vinelandii (AvNifEN). The orientation is the same as that of nitrogenase NifDK depicted in a. The NifE and NifN subunits are depicted in purple and blue ribbons, respectively. One half of the αβ2 quaternary structure is depicted in solid colors whereas the other half is transparent to further highlight the position of the cofactors corresponding to the [Fe4S4]-cluster and NifB-co (ball-and-sticks) with C, Fe and S atoms depicted in gray, brown and yellow, respectively. c, Ribbon cartoon representation of the three structures (holo-AvNifDK, apo-AvNifDK, and AvNifEN; left, center, and right, respectively; PDB IDs: 3U7Q, 1L5H, and 3PDI, respectively) in the same orientation. For clarity, only a single NifDK or NifEN heterodimer is shown. The NifD subunit of nitrogenase and the NifE subunit of the scaffold are depicted in solid colors, while the NifK and NifN subunits are shown with transparency. The three αβ-domains that constitute the NifD/E subunits are colored blue, red, and yellow (domains 1–3, respectively). The N-terminal regions defined in holo-AvNifDK and AvNifEN are highlighted in green. Cofactors are depicted in ball-and-stick representation. d, Close-up of the third αβ-domain of NifD/NifE, which exhibits all significant structural differences among the three structures. For instance, comparing holo-AvNifD with apo-AvNifD and AvNifE shows root mean square deviations of 2.7 and 5.5 Å, respectively. When comparing only their αβ-domain 3, the corresponding root mean square deviations are 6.3 and 3.9 Å, respectively. Disordered regions absent in the structures are indicated with the number of missing residues.

Extended Data Fig. 2 CryoEM holo-GmNifEN structure description and comparison with the AvNifEN crystal structure.

a, Ribbon cartoon representation of the holo-GmNifEN cryoEM structure in the same orientation as in Fig. 2b, with each subunit of GmNifEN colored according to the structural αβ-domains composing the NifE and NifN modules (NifE-module: αβ-domains 1–3 colored in blue, red, and yellow, respectively; N-module: αβ-domains 1–3 colored in green, orange, and purple, respectively). b, Front view of each NifE and NifN module, oriented identically. The [Fe4S4] cluster binding site is located at the interface between the first αβ-domains of NifE and NifN, each belonging to a different NifEN chain. c, Comparison of the P-cluster binding site in AvNifDK and the [Fe4S4] cluster binding site in GmNifEN. Top left: the P-cluster (reduced state) is coordinated by six cysteine residues, three from the NifD subunit (C62, C88, and C154; carbon atoms shown in pale yellow) and three from the NifK subunit (C70, C95, and C153; carbon atoms shown in orange). Bottom left: In the GmNifEN structure, the same region contains a [Fe4S4] cluster, coordinated by four cysteine residues — three from the NifE module (C36, C61, and C124; carbon atoms shown in mauve) and one from the NifN module (C525; carbons shown in blue). Right: Close-up view of the holo-GmNifEN [Fe4S4] cluster binding site, with the cluster shown in ball-and-stick representation. The surrounding cryoEM map contoured at 10 σ is depicted as a gold mesh. d, GmNifEN cryoEM structure in the same orientation as in panel b-left. The NifE module is shown in solid colors, while the adjacent NifN module is rendered transparent for clarity. The NifE module is color-coded from cyan to red (0 to 2.5 Å) based on root mean square deviations (RMSD) calculated from the comparison of holo-GmNifEN and AvNifEN structures. The calculation was performed using the ColorByRMSD script in PyMOL. Significant structural motions, highlighted in red, are observed exclusively around the NifB-co binding site and the third αβ-domain, emphasizing that structural differences between the two structures are confined to this specific region.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Comparison of the revisited AvNifEN and holo-GmNifEN structures.

a, Ribbon cartoon representation of the two structures (AvNifEN & holo-GmNifEN; left & right, respectively) in the same orientation as in Extended Data Fig. 2d. For clarity, only a single NifEN heterodimer is shown. The NifE subunit is depicted in solid colors, while the NifN subunit is shown with transparency. The three αβ-domains that constitute the NifE subunits are colored blue, red, and yellow (domains 1–3, respectively), while the connecting regions are shown in gray. The N-terminal regions defined in AvNifEN is highlighted in green. Cofactors are depicted in ball-and-stick representation. b, Close-up of the third αβ-domain of NifE, which exhibits all significant structural differences among the two structures (root mean square deviation: 3.1 Å overall, 1.5, 2.4 and 3.7 Å for NifE αβ-domains 1-3, respectively; Extended Data Fig. 2d). Disordered regions absent in the structures are indicated with the number of missing residues.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Detailed view of the structural changes enabling NifB-co transit within NifEN.

a, Ribbon cartoon representation of holo- and transit-GmNifEN, with color-coded αβ-domains as in Fig. 4b. b, Close-up of Fig. 4e, showing residue numbers of segments exhibiting the most significant changes and residues absent in transit-GmNifEN due to partial unfolding. The structure is color-coded from cyan to red (0 to 2.5 Å) according to root mean square deviations (RMSD) calculated by comparing holo- and transit-GmNifEN structures using the ColorByRMSD script in the molecular graphics software PyMOL (Schrödinger). c-f, Close-ups of each αβ-domain where significant changes occur during NifB-co transit. Left and middle-left: Ribbon cartoon representations of holo- and transit-GmNifEN structures, respectively. Middle-right: A morphing animation between the two structures calculated using the Morph option in PyMOL (30 steps; linear method). Morphing is shown with a gradient from purple (transit-GmNifEN) to green (holo-GmNifEN), emphasizing the extent of motions and structural remodeling for each αβ-domain. Right: The same view color-coded from cyan to red (0 to 2.5 Å) based on RMSD values, as shown in panel b.

Extended Data Fig. 5 NifB-co transfer.

a, View of the three positions where NifB-co has been observed. The GmNifEN structure is depicted as a ribbon cartoon, with one NifEN subunit in pink and the other in green. The protein is shown semi-transparent for clarity. NifB-co are displayed in a ball-and-stick representation (C, Fe, and S atoms in gray, brown, and yellow, respectively). b, Close-up view of NifB-co at the transit site, with surrounding residues depicted as sticks (C, O, and N atoms in purple, red, and blue, respectively) and NifB-co shown in ball-and-stick representation (C, Fe, and S atoms in gray, brown, and yellow, respectively). c, Cartoon representation of the sequential steps of NifB-co acquisition by NifEN.The precursor is first delivered to the docking site on NifEN by NifX. It is then inserted into the protein through extensive structural rearrangements and becomes bound within an internal cavity, where it can be further processed into FeMo-co, notably through the insertion of molybdenum and homocitrate. Presumably, FeMo-co follows the reverse pathway, using a similar mechanism, to be delivered to NafY en route to NifDK.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–7 and Tables 1–4.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Payá Tormo, L., Nguyen, TQ., Fyfe, C. et al. Dynamics driving the precursor in NifEN scaffold during nitrogenase FeMo-cofactor assembly. Nat Chem Biol (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-02070-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-02070-4