Abstract

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) and conventional in vitro fertilization (c-IVF) are widely used fertilization techniques in assisted reproduction, but their relative effectiveness in patients without severe male factor infertility remains debated. While ICSI’s role in couples with severe male factor infertility is well established, its routine use in cases with normal or nonseverely decreased sperm quality is not evidence-based. Here we conducted the INVICSI study, an open-label, multicenter randomized controlled trial, to compare cumulative live birth rates (CLBR) as the primary outcome between ICSI and c-IVF in patients without severe male factor infertility. Between November 2019 and December 2022, 824 women undergoing their first IVF cycle were randomized to ICSI (n = 414) or c-IVF (n = 410) across six public fertility clinics in Denmark. The CLBR was 43.2% (179/414) in the ICSI group and 47.3% (193/408) in the c-IVF group, yielding a risk ratio of 0.91 (95% confidence interval, 0.79–1.06). These findings demonstrate that ICSI does not improve CLBR compared to c-IVF and support c-IVF as the preferred first-line treatment for patients with normal or nonseverely decreased sperm quality. ICSI should be reserved for severe male factor infertility. ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT04128904.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), an evolved iteration of the conventional in vitro fertilization (c-IVF) method, emerged in the 1990s as a breakthrough technique for the treatment of severe male factor infertility1. ICSI involves the direct injection of a single sperm into an oocyte to overcome barriers posed by low sperm count or motility. Over recent decades, ICSI’s popularity has surged, expanding beyond its initial scope to encompass two-thirds of all fresh assisted reproductive technology (ART) cycles in Europe and globally2,3. Despite substantial variations in ART practices worldwide, with some centers now almost exclusively using ICSI for all fresh cycles4,5, its widespread adoption has prompted scrutiny into its extension to patients without male factor infertility6,7. Studies in the United States indicate a growing application of ICSI without a corresponding rise in the prevalence of male factor infertility, highlighting that this trend is primarily observed in couples without male factor infertility8,9. However, retrospective studies have failed to demonstrate any advantage of ICSI over c-IVF in terms of live birth rates in this patient group10,11,12. The additional cost burden of ICSI compared to c-IVF, often influenced by financial incentives, underscores the importance of robust, high-quality evidence to justify its use7. Recently, two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted in Asia found no improvement in live birth rate after the first embryo transfer when comparing ICSI with c-IVF among couples with normal sperm parameters and those with nonsevere male factor infertility, respectively13,14. This European contribution provides new insights by focusing on key aspects—targeting first-cycle patients, emphasizing blastocyst transfers and elective single embryo transfers (eSET) to minimize multiple pregnancies and using cumulative live birth rate (CLBR) as the primary outcome measure. The CLBR is considered the most appropriate metric for evaluating the overall effectiveness of an ART treatment regimen15,16,17,18.

Results

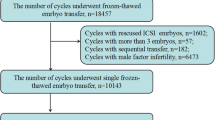

Figure 1 displays the trial profile. In total, 1,103 participants were considered eligible, and 824 were recruited between 29 November 2019 and 14 December 2022. Out of these, 414 were randomized to the ICSI group and 410 to the c-IVF group. Two participants withdrew their consent immediately after randomization and were excluded from all analyses. There were no additional exclusions. The outcomes were assessed using both an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, which included 414 participants in the ICSI group and 408 participants in the c-IVF group, and a per-protocol analysis, which included 388 participants in the ICSI group and 378 participants in the c-IVF group (Fig. 1). Individuals with unexpectedly low sperm counts (<2 million progressively motile spermatozoa) on the day of oocyte retrieval, those who mistakenly received c-IVF instead of ICSI and those with no oocytes retrieved were excluded from the per-protocol analysis (Fig. 1).

Baseline characteristics of randomized women and male partners contributing with homologous sperm are provided in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1 (ITT). In the ICSI group, 303 male partners (73.2%) provided sperm, compared to 290 male partners (71.1%) in the c-IVF group. Sperm characteristics were assessed from the sample used on the day of oocyte retrieval. Additionally, 111 women/couples (26.8%) in the ICSI group and 118 women/couples (28.9%) in the c-IVF group used donor sperm, all of which were cryopreserved. Details on ovarian stimulation are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

As of 14 December 2023, 12 months after inclusion of the last participant, the ITT analysis showed that the CLBR was 43.2% (179/414) in the ICSI group and 47.3% (193/408) in the c-IVF group (risk ratio = 0.91, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.79–1.06; Table 2). This included one spontaneous pregnancy in the ICSI group and two in the c-IVF group. In total, 110/414 (26.6%) women in the ICSI group and 129/408 (31.6%) women in the c-IVF group obtained a live birth after the first embryo transfer (spontaneous pregnancies not included). Among the 450 participants (54.7%) who did not achieve a live birth within 12 months of the last participant’s inclusion, 34 still had cryopreserved blastocysts—18 in the c-ICSI group (48 blastocysts) and 16 in the c-IVF group (47 blastocysts). The transfer-specific reproductive outcomes by group allocation are shown in Table 3. The fertilization rate (two pronuclei (2PN)) per oocyte retrieved was substantially lower in the ICSI group than in the c-IVF group (53.5% (1,940/3,628) versus 58.1% (1,983/3,412); P ≤ 0.001; Table 4). The fertilization rate (2PN) per metaphase II (MII) inseminated oocyte was only available for the ICSI group (66.6% (1,940/2,914)). Total fertilization failure (TFF) occurred in 20 cases (4.8%) in the ICSI group and 15 cases (3.7%) in the c-IVF group (risk ratio, 1.29; 95% CI, 0.68–2.54). Time to viable pregnancy leading to live birth did not differ between the groups (median, ICSI—90 days interquartile range (IQR; 42–158) versus c-IVF—93 days IQR (43–127); P = 0.82). The time taken for 25% of the population to achieve a live birth was 331 days in the ICSI group and 320 days in the c-IVF group. There was no difference between the two groups in obstetric and perinatal outcomes (Table 5 and Supplementary Table 3).

In the per-protocol analysis, the CLBR was 43.0% (167/388) in the ICSI group and 49.2% (186/378) in the c-IVF group (risk ratio = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.75–1.02; Supplementary Table 4). The live birth rate after the first embryo transfer was higher in the c-IVF group at 33.3% (126/378) compared to 26.5% (103/388) in the ICSI group (risk ratio = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.64–0.99). More participants in the c-IVF group had more than one live birth compared to the ICSI group (c-IVF—16/378 (4.2%) versus ICSI—6/388 (1.5%); risk ratio = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.13–0.88). Overall, the remaining results of the per-protocol analyses were consistent with the ITT analysis (Supplementary Tables 5–9).

Individuals who declined participation were asked about their reasons, and among those who responded, the majority cited a preference to ensure treatment with c-IVF rather than ICSI (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Regarding safety, all trial sites handling the ICSI and c-IVF procedures were authorized by the Danish Patient Safety Authority. Pregnancy, perinatal and neonatal outcomes related to safety were registered; however, specific safety outcomes were not prespecified as such in the study protocol. These included, but were not limited to, pregnancy loss, ectopic pregnancy, bleeding in early pregnancy, gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes, intrahepatic cholestasis, preterm birth, postpartum bleeding, fetal death/stillborn, low (<2,500 g) and high (>4,500 g) birth weight of the baby and congenital malformations. Both ICSI and c-IVF are well established and widely used methods with known safety profiles beyond pregnancy and birth-related outcomes and were not specifically evaluated in this study.

The secondary analysis showed a negative effect of ICSI compared to c-IVF on younger women (≤32 years of age; Extended Data Fig. 1). In this group, number needed to harm was nine, suggesting that one less live birth would occur for every nine couples/women treated with ICSI instead of c-IVF. The analysis also showed an interaction between ovarian response and allocated group with a negative effect of ICSI versus c-IVF in those with a ‘normal’ ovarian response (10–15 oocytes retrieved; Extended Data Fig. 2). Sperm morphology, normal sperm parameters, treatment indication, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and trial center had no effect on CLBR (Supplementary Table 9).

A secondary analysis was conducted, excluding the 86 participants enrolled before 16 September 2020, when Amendment 4 was implemented. This amendment removed the requirement for at least 5 million progressively motile spermatozoa in a purified diagnostic semen sample and instead introduced a requirement for at least 2 million progressively motile spermatozoa in the purified sample on the day of oocyte retrieval (Supplementary Table 10). Before this, Amendment 2, implemented on 20 March 2020, had removed the inclusion criterion requiring sperm morphology ≥4%. The analysis confirmed that the primary outcome results remained consistent.

Supplementary Table 11 presents the primary outcome by center for both the ITT and per-protocol populations.

Discussion

We found no benefit of ICSI over c-IVF in fertility patients without severe male factor infertility measured in CLBR. There was no improvement in ongoing pregnancy rates or implantation rates following ICSI. These results are consistent with the outcomes of prior RCTs from other countries13,14,19, as well as large retrospective studies9,10,11,20 and a recently updated Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis21. With the addition of our European study, the cross-continental execution of these RCTs enhances the external validity of the results by capturing diverse populations and practices. We demonstrated better fertilization rates (per oocyte retrieved) after c-IVF than after ICSI. This aligns with earlier smaller RCTs and extensive retrospective studies, which have demonstrated either higher fertilization rates with c-IVF11,19 or no notable difference between the two approaches22,23. The RCT in ref. 14 found comparable fertilization rates between c-IVF and ICSI. However, our findings differ from the results given in ref. 13, which showed higher fertilization rates after ICSI (per oocyte retrieved and per MII inseminated), a result that was also supported by a recent extensive retrospective study24. In our study, the fertilization rate (2PN) per MII inseminated oocyte was only calculated for the ICSI group, as this aligns with standard practice where MII oocytes are typically injected. In c-IVF, all retrieved oocytes, regardless of maturation status, are exposed to spermatozoa, making it less relevant to use MII oocytes as the denominator when calculating fertilization rates. While some might argue that c-IVF allows for additional oocyte maturation during insemination, potentially leading to higher fertilization rates, this distinction does not reflect everyday practice in the clinics. The strength of this study lies in its multicenter RCT design with a substantial participant cohort, no loss to follow-up on our primary outcome and a focus on first-cycle patients, substantially reducing inclusion bias. The use of the CLBR mitigated potential bias in embryo selection, ensuring a robust analysis of overall efficacy in ICSI/c-IVF cycles. Aligning with the gold standards within ART25, all embryo transfers in our study were single embryo transfers, and >96% of transfers in both groups were blastocyst transfers. In this regard, our study differs from previous RCTs, as they predominantly used cleavage stage and double embryo transfers13,14. The study population, which includes patients using donor sperm and couples with both normal and nonseverely decreased sperm quality (for whom ICSI was originally not meant), secures a certain generalizability of our results, providing more relevant insights into the comparative effectiveness of ICSI and c-IVF in real-world scenarios. Furthermore, we did not define nonsevere male infertility solely based on basic semen analysis parameters. Instead, we included all couples who would typically be treated with c-IVF in our clinical practice, categorizing them as having normal or nonseverely decreased sperm quality. Operationally, this included those expected to have at least 2 million progressively motile spermatozoa in the purified sperm sample, based on diagnostic sperm samples of varying comprehensiveness, reflecting routine clinical practice. Although there is no definitive consensus in the literature regarding the optimal sperm concentration threshold after purification for c-IVF, in Denmark, it is generally accepted to perform ICSI when the count falls below 2 million progressively motile spermatozoa—a threshold based on empirical evidence and an accepted practice among experts in the field. In our per-protocol analysis, which excluded those who fell below this threshold on the day of oocyte retrieval and those who received treatment inconsistent with their allocated group, CLBR remained nonsuperior following ICSI compared to c-IVF, supporting that patients without severe male factor should be offered c-IVF rather than ICSI. However, the study does have limitations. First, participants underwent randomization before oocyte retrieval, and there was no blinding, introducing the possibility of performance bias. The decision against blinding was practical, and we had no interest in favoring one method over the other. All outcome measures were quantitative, leading us to conclude that the risk of bias without blinding was not considered substantial. Second, normal sperm morphology (>4%) was removed as an inclusion criterion as part of the study amendments due to inconsistencies in diagnostic sperm samples across fertility clinics. Some sites lacked data on sperm morphology altogether, while others only used microscopy without staining. We opted to include only data from sperm smears stained with Papanicolaou, limiting morphology assessments to 40% of male partners in the study. Notably, these assessments are based on samples taken before oocyte retrieval rather than contemporaneously. Despite the limited availability of morphology data, our secondary analysis indicated that sperm morphology did not substantially affect the CLBR. Historically, sperm morphology has been pivotal in assessing sperm quality for IVF. However, its clinical relevance is now being re-evaluated due to conflicting findings regarding reproductive outcomes in patients with teratozoospermia (low percentage of morphologically normal sperm) undergoing ART26,27. Theoretically, it would be reasonable to expect that sperm morphology has only a modest role in ICSI and could potentially be somewhat more influential in c-IVF. Finally, the timing of randomization warrants discussion. Randomizing after oocyte retrieval could potentially reduce biases affecting clinicians and patients. It would also have avoided the inclusion of participants who did not proceed to oocyte retrieval or whose sperm sample did not meet the inclusion criteria. That said, these participants were retained in the ITT analysis, reflecting real-world clinical practice where not all cycles result in oocyte retrieval. The per-protocol analysis, excluding participants without oocyte retrieval and those with less than 2 million progressively motile spermatozoa, showed consistent results for the primary outcome. On the other hand, randomizing before ovarian stimulation could avoid any potential inflation of CLBR that might occur if only those who advance to oocyte retrieval are included18. We chose our timing of randomization for several reasons. One consideration was alignment with established clinic protocols, where ICSI preparations were customarily performed 1 day before insemination. Another factor was minimizing the influence of group assignment on clinicians’ decisions regarding follicle-stimulating hormone dosage or scheduling (or possible cancellation) of oocyte retrieval by randomizing immediately following the prescription of the ovulation trigger. Although we chose not to implement blinding, we do not consider the lack of blinding or randomization before oocyte retrieval to have introduced substantial performance bias. This is partly due to the use of objective, quantitative outcomes and the setting of the study in public fertility clinics in Denmark, where infertility treatment is publicly funded. In this context, there is no financial incentive to use ICSI unless it demonstrably improves live birth rates28. Instead, the resources allocated to ICSI as an unnecessary add-on could be better utilised to fund additional treatment cycles for more patients. The CLBR presented here is calculated per started cycle leading to ovulation trigger, not per cycle started. Nonetheless, the risk of overestimating success rates by not randomizing before the start of stimulation is limited because we offered inclusion and trigger to patients even with just one mature follicle, and some ultimately had no oocytes retrieved, as shown in our flowchart (Fig. 1). Additionally, because this study focuses on comparing fertilization methods, the outcomes are most relevant to patients reaching the fertilization stage. Any potential overestimation of CLBR would likely affect both the ICSI and c-IVF groups equally.

In our secondary analysis, we found that among younger women (≤32 years of age), ICSI might be associated with a reduced likelihood of live birth, with a notable number needed to harm of just nine. Furthermore, normal ovarian response was linked to a decreased chance of live birth following ICSI compared with c-IVF. This may reflect the advantage of the natural selection process in c-IVF, where the most suited sperm fertilizes the oocyte, particularly in women with optimal conditions (young age and many oocytes). In contrast, ICSI may be more beneficial in women with poorer ovarian response, where assisted fertilization compensates for lower oocyte quality. Additionally, there may be a ‘hidden’ oocyte factor in women with optimal conditions that makes their oocytes more vulnerable to the invasive manipulation involved in ICSI. ICSI might cause mechanical damage to the oocyte by disrupting its internal structures and cytoskeleton during sperm injection, potentially leading to a process that does not adequately mimic natural sperm penetration and activation. It is still debated whether this disruption (and potential selection of sperm with DNA damage or structural issues) could also be associated with a slightly increased risk of chromosomal abnormalities in the resulting embryos29. Oocyte damage can occur at the following three stages during the ICSI process: starting from the denudation stage, during the ICSI injection itself or at the fertilization assessment on day 1 (if time-lapse incubators are not used). Most likely, oocyte damage occurs most frequently during the injection stage30. Although some may argue that the exclusion of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies (PGT-A) in this study limits generalizability, this was a deliberate design choice, given the current inefficacy of PGT-A. While ICSI can minimize the risk of sperm DNA contamination in biopsy samples, this issue has become less relevant with modern techniques. Furthermore, ICSI does not improve overall success rates with PGT-A compared to c-IVF31,32,33. The critical factor determining success is not the ploidy status of the embryos but rather the CLBR, which remains independent of the fertilization technique used. Some clinics use ICSI for all treatments involving cryopreserved sperm. However, there is no evidence supporting this practice. In couples treated with IUI, studies have shown no difference in live birth rates or cumulative pregnancy rates between cryopreserved and fresh sperm34. Our secondary analysis showed that the use of cryopreserved sperm (all donor sperm cases in this study) had no effect on CLBR. The rationale behind using ICSI in cases of nonmale-factor infertility has often been to reduce the risk of unexpected TFF after c-IVF, for instance, in patients with unexplained infertility35,36. Neither our RCT nor the previous RCTs showed any increased risk of TFF after c-IVF13,14, and our secondary analysis revealed no benefit of ICSI over c-IVF in the group of participants with unexplained infertility. Our findings suggest that there is no clear advantage of ICSI over c-IVF in the first treatment cycles, and we do not expect this outcome to differ in subsequent cycles, provided there is no prior history of TFF. It is yet to be proven if there is a justified role for ICSI in fertility patients who have experienced previous TFF with c-IVF37,38. Recent data suggest that performing ICSI on oocytes that fail to fertilize after c-IVF—known as ‘rescue ICSI’—may warrant further investigation. While historically linked to poor outcomes, newer studies indicate that combining it with blastocyst vitrification could offer respectable live birth rates39,40. Considering the growing application of ICSI, it is crucial to take both immediate and long-term health implications into account. Conflicting findings arise in various studies regarding the association of ICSI with an elevated risk of congenital malformations, as well as the specific types of malformations involved29,41,42. Similarly, debates persist regarding the potentially heightened risks of neurodevelopmental disorders43,44,45,46,47,48 and cancer49,50 when performing ICSI. In this study, we found no increased risk of congenital malformations in the ICSI group, and, in general, perinatal and obstetric outcomes were comparable between the groups. However, the study was not powered to robustly detect differences in these outcomes. In IVF cycles performed in US fertility clinics, mandates for IVF insurance coverage are associated with lower ICSI use in nonmale-factor infertility cycles compared to states where insurance does not cover IVF costs51, highlighting the financial considerations associated with ICSI use. The use of ICSI, like other IVF add-ons, should be guided by robust scientific evidence rather than influenced by the financial incentives of a profit-driven fertility industry28.

In conclusion, ICSI does not result in superior CLBRs compared to c-IVF in fertility patients without severe male factor infertility. Given the substantial evidence from this and previous studies, it is imperative to reconsider the routine use of ICSI in patients without severe male factor infertility. This study demonstrates that when adhering to the current gold standards of ART treatment, specifically blastocyst transfer and eSET, treating couples without severe male factor infertility with ICSI over c-IVF offers no benefits. C-IVF is safe, straightforward and gentle on both oocytes and sperm, making it more cost-effective and resource-efficient in first-cycle patients compared to ICSI. Clinical practice should ensure that the most effective and least invasive treatments are prioritized, ultimately improving patient outcomes and resource allocation in ART.

Methods

Study design

The c-IVF versus ICSI in patients without severe male factor infertility study (INVICSI) was an open-label, multicenter, RCT using a parallel arm design. Participants were recruited from six public university hospitals in Denmark. The study was registered with the National Institute of Health (ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT04128904) on 10 July 2019, and protocol modifications were registered continuously. The study was prospectively registered before enrolling the first patient. Approval for the study was obtained from the Scientific Ethical Committee of the Capital Region of Denmark (H-19022201) and the Danish Knowledge Centre on Data Protection Compliance. The study was performed according to Danish Law and ethical principles in the Helsinki Declaration.

Participants

All couples and single women referred for their first fertility treatment (c-IVF/ICSI) at the clinics were screened for eligibility. Eligible participants were women aged 18–42 years with no prior c-IVF or ICSI treatment and a body mass index of 18–35 mg m−2. Participants were considered eligible if they qualified for c-IVF treatment, which required male partner sperm containing a minimum of 2 million progressively motile spermatozoa (after density gradient purification, wash steps and resuspension), or if donor sperm was to be used. Suitability for c-IVF was assessed by the treating clinician based on the results of prior diagnostic sperm analyses, which varied in methodology but were consistently available for all couples using male partner sperm. Details regarding the different forms of diagnostic sperm samples are provided in the Additional methods: procedures. Women with severe comorbidity (including ovarian cysts >4 cm, liver or kidney disease, unregulated thyroid disease, endometriosis stage 3–4, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism or other severe comorbidities such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease) and couples/women using donor oocytes or frozen oocytes were not included. In this study, ethnicity was determined based on the participants’ country or region of birth, as well as the birthplaces of their parents and grandparents. This information was collected to provide a description of the study population. No analyses based on ethnicity were planned.

Randomization and masking

Potentially eligible patients received verbal and written information about the study from the investigators during one of their consultations in the fertility clinic. Inclusion and randomization took place after the ovulation trigger was prescribed and before oocyte retrieval. Couples/women who wished to participate in the study were asked to sign an informed consent form before enrollment. Randomization and data collection were executed through the online platform REDCap52. For the randomization process, a statistician who was not involved in any other parts of the study devised a computer-generated randomization scheme, maintaining a 1:1 ratio between the two arms (c-IVF and ICSI). Randomization involved permuted blocks of varying sizes, ranging from 4 to 12. It was stratified by trial site and female age, categorized into the following three age groups: 18–25 years, 26–37 years and 38–42 years. The allocation table was uploaded into REDCap, and the system was set to production status by the statistician. The allocation table was locked and unmodifiable. Clinical staff had no access to view the allocation table. To randomize a participant, the clinical staff entered baseline participant data, and the system automatically assigned the allocation group. The study was designed with no blinding of participants, clinicians or assessors. While data entry for individual participants into the REDCap database was not blinded, access to extract and analyze data was strictly controlled. Only those responsible for the study (S.B. and N.l.C.F.) had access to extract data from the database before 12 months after the randomization of the final participant. After this period, on 14 December 2023, two statisticians were granted access to the data; however, the randomization group and method of fertilization were blinded to them during their analyses. No data were extracted before the follow-up end date, and no interim analysis was planned or conducted during the study.

Procedures

Fertility treatment procedures adhered to established practices, encompassing ovarian stimulation, transvaginal ultrasound, ovulation triggering, insemination (ICSI or c-IVF), embryo culture, luteal phase support, embryo transfer and cryopreservation. If progressively motile spermatozoa postpurification fell unexpectedly below 2 million, ICSI was performed irrespective of allocation. Single blastocyst transfer occurred on day 5. For cases with ≤4 retrieved oocytes, transfer on day 2 or 3 was permitted but not mandatory. Surplus blastocysts of good quality were vitrified on day 5 or 6. PGT-A was not allowed. Details regarding ovarian stimulation, ovulation trigger and additional treatment specifics, including sperm sample evaluation, are outlined in the Additional methods: procedures and the study protocol53.

Serum pregnancy tests were conducted 11–16 days postembryo transfer, with transvaginal ultrasound scans performed during pregnancy weeks 7–9 to confirm ongoing pregnancies. Participants received standard clinical care throughout the pregnancy and neonatal period.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the CLBR, defined as at least one live birth after completing an ART cycle, which includes the initial fresh embryo transfer and all subsequent frozen-thawed embryo transfers (FETs) from that cycle. The follow-up period was 12 months after the inclusion of the last participant, meaning that all embryos transferred within this timeframe were included in the reported numbers of pregnancies and live births. Live birth was defined as the delivery of one or more living infants at or beyond 22 weeks of gestation. Secondary outcomes included live birth after the first embryo transfer and the number of participants with more than one live birth. CLBR was prespecified as an outcome of the trial registration. Live birth after the first transfer was introduced later to improve comparability with live birth data reported by two other RCTs, which ran concurrently with our study13,14 Similarly, the additional secondary outcomes following the first transfer were not prespecified as secondary outcomes. Prespecified secondary outcomes are detailed in the study protocol53.

Amendments

In March 2020, an amendment was made to remove the following two inclusion criteria: (1) regular menstrual cycles (21–35 days) and (2) a diagnostic sperm sample from the male partner with ≥4% morphologically normal spermatozoa. A subsequent amendment in September 2020 eliminated the requirement for a minimum of 5 million progressive motile spermatozoa in a purified diagnostic sperm sample, originally chosen to account for the timing of randomization after the ovulation trigger. This margin, from 5 million in the diagnostic sample to 2 million on the day of retrieval, aimed to minimize the number of participants requiring ICSI irrespective of their allocated group. The new criterion focused on a sperm sample, purified on the day of oocyte retrieval, expected to contain at least 2 million progressive motile spermatozoa. This change was implemented to adopt a more clinically practical approach, allowing for the inclusion of all patients expected to have at least 2 million progressive motile spermatozoa on the day of oocyte retrieval. A comprehensive overview of the amendments can be found in Supplementary Table 10.

Statistical analysis

The study was designed as a superiority trial with 80% power and a 5% significance level for a two-sided test, aiming to detect a 10% point difference in CLBR. The expected rate of first live births after the transfer of all available embryos from the initial oocyte retrieval was set at 45% in the c-IVF group and 55% in the ICSI group. This rate was based on data from the general population treated across the participating clinics, reflecting a diverse patient population. The estimated sample size was 824 patients, with primary analysis conducted using an ITT approach. Cumulative live birth from the initiated first cycle until the end of the study (12 months after randomization of the last participant) was calculated, and the live birth rate after the first embryo transfer between groups was compared using risk ratio and risk difference, with corresponding 95% CIs. Secondary analyses included a per-protocol analysis and analyses examining the impact of treatment across various factors, including maternal age, IVF indications, trial centers, ovarian response, AMH, sperm morphology and normal sperm parameters (lower reference levels for semen volume, total sperm number, sperm concentration and total motility (World Health Organization (WHO) sixth edition)). All secondary analyses, except for the per-protocol analysis, were defined postdata collection as outlined in the statistical analysis plan.

All statistical analysis was done using R (v4.2.2), using the packages sjPlot (v2.8.15) and marginal effects (v0.18.0).

Sex and gender considerations

No sex or gender analysis was carried out, as the study population enrolled only female participants assigned female sex at birth and male partners or sperm donors, with a focus on their biological contributions to the outcomes.

Additional methods: procedures

Diagnostic sperm samples

Results from prior diagnostic sperm samples were available for all couples using male partner sperm. The diagnostic sperm sample could take one of the following forms: (1) a complete semen analysis, (2) a diagnostic sperm sample including total sperm count, concentration, (±) motility and progressive motility, (3) a simple diagnostic sperm sample including total sperm count, concentration and motility or (4) a basic sperm sample including only volume and concentration. To meet eligibility criteria, the recruiting clinician had to assess that, on the day of oocyte retrieval, the sperm sample, following density gradient purification, was likely to contain a minimum of 2 million progressively motile spermatozoa.

Ovarian stimulation

The women were treated using either a short gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-antagonist protocol or a long GnRH-agonist protocol for ovarian stimulation. Ovarian stimulation, transvaginal ultrasound examinations and ovulation triggering followed standard practices at the trial sites. Typically, the ovulation trigger was prescribed when at least two to three follicles measured 17 mm or more. However, women with only one mature follicle could also receive the trigger. Oocyte retrieval occurred 36 ± 2 h after the ovulation trigger was administered.

Evaluation of sperm sample on the day of oocyte retrieval

On the day of oocyte retrieval, the concentrations of all spermatozoa and motile spermatozoa in the ejaculate were assessed. After density gradient purification, wash steps and resuspension in 1 ml media, the number of all spermatozoa and motile spermatozoa was re-evaluated, and the number of progressive motile spermatozoa was assessed. When the ejaculate exhibited a high spermatozoa concentration, the option to purify only a portion of the sample was considered. In such scenarios, a theoretical total yield after purification could be calculated.

Oocyte insemination and embryo transfer

Oocyte insemination was conducted through either ICSI or c-IVF, based on randomization, following established procedures at the trial sites. In the c-IVF group, oocyte–corona cumulus complexes were inseminated with semen samples containing 0.1–0.3 × 10−6 progressively motile sperm per milliliter. If the total number of progressive motile spermatozoa after purification unexpectedly was <2 million, ICSI was performed regardless of allocation. In cases of TFF, rescue ICSI was not performed. Embryo culture and luteal phase support adhered to standard procedures at each trial site. Blastocyst transfer occurred on day 5. In cases of poor ovarian reserve with few retrieved oocytes (≤4), transfer on day 2 or 3 was allowed. Single embryo transfers were planned, and any surplus blastocysts of good quality were vitrified on day 5 or 6. Transfer and cryopreservation followed the usual practices at the trial sites. If all blastocysts were vitrified due to the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (or in cases where there were only day 6 blastocysts), women were not excluded from the trial, as the primary outcome (CLBR) includes subsequent FET cycles. FET cycles were performed in accordance with the daily practice at each trial site (that is, modified natural, substituted or stimulated FET cycles).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are subject to controlled access due to privacy and legal regulations under Danish law. Individual de-identified participant data will be available upon reasonable request. Access will require approval from the Health Research Ethics Committees for the Capital Region of Denmark (H-19022201) and compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation. Requests can be directed to N.l.C.F. and will be reviewed within 4 weeks.

Code availability

No custom computational code or software was developed for this study. Analyses were performed with publicly available software packages as described in the Methods.

References

Palermo, G., Joris, H., Devroey, P. & Van Steirteghem, A. C. Pregnancies after intracytoplasmic injection of single spermatozoon into an oocyte. Lancet 340, 17–18 (1992).

European IVF Monitoring Consortium (EIM), for the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) et al. ART in Europe, 2018: results generated from European registries by ESHRE. Hum. Reprod. Open 2022, hoac022 (2022).

Banker, M. et al. International committee for monitoring assisted reproductive technologies (ICMART): world report on assisted reproductive technologies, 2013. Fertil. Steril. 116, 741–756 (2021).

Mansour, R., El-Faissal, Y. & Kamal, O. The Egyptian IVF registry report: assisted reproductive technology in Egypt 2005. Middle East Fertil. Soc. J. 19, 16–21 (2014).

Chambers, G. M. et al. International committee for monitoring assisted reproductive technologies world report: assisted reproductive technology, 2014. Hum. Reprod. 36, 2921–2934 (2021).

Evers, J. L. Santa Claus in the fertility clinic. Hum. Reprod. 31, 1381–1382 (2016).

Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) for non-male factor indications: a committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 114, 239–245 (2020).

Boulet, S. L. et al. Trends in use of and reproductive outcomes associated with intracytoplasmic sperm injection. JAMA 313, 255–263 (2015).

Zagadailov, P., Hsu, A., Stern, J. E. & Seifer, D. B. Temporal differences in utilization of intracytoplasmic sperm injection among U.S. regions. Obstet. Gynecol. 132, 310–320 (2018).

Schwarze, J. E. et al. Is there a reason to perform ICSI in the absence of male factor? Lessons from the Latin American Registry of ART. Hum. Reprod. Open 2017, hox013 (2017).

Li, Z. et al. ICSI does not increase the cumulative live birth rate in non-male factor infertility. Hum. Reprod. 33, 1322–1330 (2018).

Tannus, S. et al. The role of intracytoplasmic sperm injection in non-male factor infertility in advanced maternal age. Hum. Reprod. 32, 119–124 (2017).

Dang, V. Q. et al. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection versus conventional in-vitro fertilisation in couples with infertility in whom the male partner has normal total sperm count and motility: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 397, 1554–1563 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection versus conventional in-vitro fertilisation for couples with infertility with non-severe male factor: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 403, 924–934 (2024).

Maheshwari, A., McLernon, D. & Bhattacharya, S. Cumulative live birth rate: time for a consensus? Hum. Reprod. 30, 2703–2707 (2015).

Humaidan, P., La Marca, A., Alviggi, C., Esteves, S. C. & Haahr, T. Future perspectives of POSEIDON stratification for clinical practice and research. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 10, 439 (2019).

Cornelisse, S. et al. Women’s preferences concerning IVF treatment: a discrete choice experiment with particular focus on embryo transfer policy. Hum. Reprod. Open 2022, hoac030 (2022).

Wilkinson, J., Roberts, S. A. & Vail, A. Developments in IVF warrant the adoption of new performance indicators for ART clinics, but do not justify the abandonment of patient-centred measures. Hum. Reprod. 32, 1155–1159 (2017).

Bhattacharya, S. et al. Conventional in-vitro fertilisation versus intracytoplasmic sperm injection for the treatment of non-male-factor infertility: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 357, 2075–2079 (2001).

Drakopoulos, P. et al. ICSI does not offer any benefit over conventional IVF across different ovarian response categories in non-male factor infertility: a European multicenter analysis. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 36, 2067–2076 (2019).

Cutting, E., Horta, F., Dang, V., van Rumste, M. M. & Mol, B. W. J. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection versus conventional in vitro fertilisation in couples with males presenting with normal total sperm count and motility. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 8, CD001301 (2023).

Foong, S. C. et al. A prospective randomized trial of conventional in vitro fertilization versus intracytoplasmic sperm injection in unexplained infertility. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 23, 137–140 (2006).

Haas, J. et al. The role of ICSI vs. conventional IVF for patients with advanced maternal age—a randomized controlled trial. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 38, 95–100 (2021).

Supramaniam, P. R. et al. ICSI does not improve reproductive outcomes in autologous ovarian response cycles with non-male factor subfertility. Hum. Reprod. 35, 583–594 (2020).

ESHRE Guideline Group on the Number of Embryos to Transfer. et al. ESHRE guideline: number of embryos to transfer during IVF/ICSI. Hum. Reprod. 39, 647–657 (2024).

Hotaling, J. M., Smith, J. F., Rosen, M., Muller, C. H. & Walsh, T. J. The relationship between isolated teratozoospermia and clinical pregnancy after in vitro fertilization with or without intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 95, 1141–1145 (2011).

Demir, B. et al. Effect of sperm morphology on clinical outcome parameters in ICSI cycles. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 39, 144–146 (2012).

The Lancet. The fertility industry: profiting from vulnerability. Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01484-3 (2024).

Berntsen, S. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the association between ICSI and chromosome abnormalities. Hum. Reprod. Update 27, 801–847 (2021).

ESHRE Special Interest Group of Embryology and Alpha Scientists in Reproductive Medicine.The Vienna consensus: report of an expert meeting on the development of ART laboratory performance indicators. Reprod. Biomed. Online 35, 494–510 (2017).

Tozour, J. N. et al. Comparison of outcomes between intracytoplasmic sperm injection and in vitro fertilization inseminations with preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy, analysis of Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Clinic Outcome Reporting System data. Fertil. Steril. 121, 799–805 (2024).

Feldman, B. et al. Pre-implantation genetic diagnosis-should we use ICSI for all? J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 34, 1179–1183 (2017).

De Munck, N. et al. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection is not superior to conventional IVF in couples with non-male factor infertility and preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies (PGT-A). Hum. Reprod. 35, 317–327 (2020).

Cherouveim, P. et al. The impact of cryopreserved sperm on intrauterine insemination outcomes: is frozen as good as fresh?. Front. Reprod. Health 5, 1181751 (2023).

Abbas, A. M. et al. Higher clinical pregnancy rate with in-vitro fertilization versus intracytoplasmic sperm injection in treatment of non-male factor infertility: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 49, 101706 (2020).

Johnson, L. N., Sasson, I. E., Sammel, M. D. & Dokras, A. Does intracytoplasmic sperm injection improve the fertilization rate and decrease the total fertilization failure rate in couples with well-defined unexplained infertility? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 100, 704–711 (2013).

Krog, M. et al. Fertilization failure after IVF in 304 couples—a case-control study on predictors and long-term prognosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 184, 32–37 (2015).

Van der Westerlaken, L., Helmerhorst, F., Dieben, S. & Naaktgeboren, N. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection as a treatment for unexplained total fertilization failure or low fertilization after conventional in vitro fertilization. Fertil. Steril. 83, 612–617 (2005).

Batha, S. et al. Day after rescue ICSI: eliminating total fertilization failure after conventional IVF with high live birth rates following cryopreserved blastocyst transfer. Hum. Reprod. 38, 1277–1283 (2023).

Paffoni, A. et al. Should rescue ICSI be re-evaluated considering the deferred transfer of cryopreserved embryos in in-vitro fertilization cycles? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 19, 121 (2021).

Henningsen, A. A. et al. Risk of congenital malformations in live-born singletons conceived after intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a Nordic study from the CoNARTaS group. Fertil. Steril. 120, 1033–1041 (2023).

Luke, B. et al. The risk of birth defects with conception by ART. Hum. Reprod. 36, 116–129 (2021).

Kissin, D. M. et al. Association of assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment and parental infertility diagnosis with autism in ART-conceived children. Hum. Reprod. 30, 454–465 (2015).

Djuwantono, T., Aviani, J. K., Permadi, W., Achmad, T. H. & Halim, D. Risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in children born from different ART treatments: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurodev. Disord. 12, 33 (2020).

Norrman, E., Petzold, M., Bergh, C. & Wennerholm, U. B. School performance in singletons born after assisted reproductive technology. Hum. Reprod. 33, 1948–1959 (2018).

Spangmose, A. L. et al. Academic performance in adolescents born after ART—a nationwide registry-based cohort study. Hum. Reprod. 32, 447–456 (2017).

Catford, S. R., McLachlan, R. I., O’Bryan, M. K. & Halliday, J. L. Long-term follow-up of ICSI-conceived offspring compared with spontaneously conceived offspring: a systematic review of health outcomes beyond the neonatal period. Andrology 6, 635–653 (2018).

Sundh, K. J. et al. Cancer in children and young adults born after assisted reproductive technology: a Nordic cohort study from the Committee of Nordic ART and Safety (CoNARTaS). Hum. Reprod. 29, 2050–2057 (2014).

Lerner-Geva, L. et al. Possible risk for cancer among children born following assisted reproductive technology in Israel. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 64, e26292 (2017).

Spaan, M. et al. Cancer risk in children, adolescents, and young adults conceived by ART in 1983–2011. Hum. Reprod. Open 2023, hoad027 (2023).

Dieke, A. C. et al. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection use in states with and without insurance coverage mandates for infertility treatment, United States, 2000–2015. Fertil. Steril. 109, 691–697 (2018).

Harris, P. A. et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 42, 377–381 (2009).

Berntsen, S. et al. In vitro fertilisation (IVF) versus intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) in patients without severe male factor infertility: study protocol for the randomised, controlled, multicentre trial INVICSI. BMJ Open 11, e051058 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to all the individuals who participated in this study. Our thanks extend to the embryologists at the fertility clinics for their dedicated work in the laboratory, and we deeply appreciate the efforts of the study nurses who assisted in informing patients about the project and organizing their inclusions. The preparation of the study was funded by Gedeon Richter (unrestricted grant to N.l.C.F.). The INVICSI study was funded by the Capital Region of Denmark (A6606 to N.l.C.F.), Gedeon Richter (unrestricted grant to N.l.C.F.), Læge Sophus Carl Emil Friis og hustru Olga Doris Friis’ Legat (4101466 to S.B.) and Amager/Hvidovre Hospital (to S.B.). The funders did not have a role in determining the study design, conducting data collection, performing analysis, interpreting results, contributing to manuscript writing or deciding on manuscript submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.l.C.F. and S.B. contributed to the research conception and design of the study, secured funding for the study, are the guarantors of the work and accept full responsibility for the integrity of the study and the decision to publish. S.B., A.Z., B.N., M.R.P., M.L.G., L.F.A., K.L., E.L., A.L.E., A.V.G., L.P., I.B.-M., L.L.T., K.V., M.P.L., A.I.T., A.P., H.S.N. and N.l.C.F. were involved in patient inclusions and data acquisition. D.F.S., D.W., S.B., N.l.C.F. and H.S.N. performed the analysis and interpretation of data. D.W., D.F.S. and S.B. conducted statistical analysis. S.B. drafted the initial manuscript with inputs from N.l.C.F. All authors critically revised the manuscript and contributed to the final drafting. All authors had full access to all the data in the study. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors have completed the ICMJE (International Committee of Medical Journal Editors) uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/. K.L., A.P., B.N. and K.V. have received scientific grants and personal payments/honoraria from Gedeon Richter, Ferring Pharmaceuticals and Merck. They have also received support for attending meetings from these companies. A.P. has additionally received consulting fees for lectures and presentations from Novo Nordisk, Cryos and Organon. A.L.E., L.P. and B.N. are on advisory boards for Ferring Pharmaceuticals. B.N. is also on the advisory board for Merck. N.l.C.F. has received scientific grants from Gedeon Richter, Merck and Cryos, and has received consulting fees from Merck and support for meetings from Gedeon Richter, Merck, Ferring Pharmaceuticals and IBSA (Institut Biochimique SA). E.L. received personal payments/honoraria for lectures and presentations from Pfizer and is on the advisory board for Astellas Pharma Nordic. M.L.G. has received scientific grants from Gedeon Richter, Cooper Surgical and Merck, as well as personal payments/honoraria for lectures and presentations from Merck. H.S.N. has received scientific grants from Freya Biosciences, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, BioInnovation Institute, Ministry of Education, Novo Nordisk Foundation, Augustinus Fonden, Oda og Hans Svenningsens Fond, Demant Fonden, Independent Research Fund Denmark and Ole Kirks Fond and has received personal payments/honoraria for lectures and presentations from Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Merck, AstraZeneca, Cook Medical, Gedeon Richter, Novo Nordisk and IBSA. S.B. received scientific grants from Gedeon Richter and Læge Sofus Carl Emil Friis og Hustru Olga Doris Friis’ Fond. A.I.T. received support for attending meetings from Ferring Pharmaceuticals and Gedeon Richter. A.Z., M.R.P., L.F.A., A.V.G., I.B.-M., L.L.T., M.P.L., D.F.S. and D.W. declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Sebastiaan Mastenbroek, Mats Pihlsgård, Sesh Kamal Sunkara and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: L. Messin and S. Muliyil, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 CLBR and risk difference stratified by maternal age at randomization (LRT = 1.79 × 10−9).

The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval, as estimated using ITT population (ICSI, n = 414; c-IVF, n = 408). CLBR, cumulative live birth rate; LRT, likelihood ratio test.

Extended Data Fig. 2 CLBR and risk difference stratified by ovarian response (LRT = 1.23 × 10−9).

The error bars represent the 95% confidence interval, as estimated using ITT population (ICSI, n = 414; c-IVF, n = 408). CLBR, cumulative live birth rate; LRT, likelihood ratio test.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–11 and Supplementary Fig. 1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Berntsen, S., Zedeler, A., Nøhr, B. et al. IVF versus ICSI in patients without severe male factor infertility: a randomized clinical trial. Nat Med 31, 1939–1948 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03621-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03621-x

This article is cited by

-

Crosstalk between H3K4me3 and oxidative stress is a potential target for the improvement of ART-derived embryos

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Kumulative Lebendgeburtenrate nach ICSI- oder konventioneller IVF-Therapie – bei ausreichender Spermienqualität vergleichbar

Gynäkologische Endokrinologie (2025)