Abstract

Adoptive transfer of unselected autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) has mediated meaningful clinical responses in patients with metastatic melanoma but not in cancers of gastrointestinal epithelial origin. In an evolving single-arm phase 2 trial design, TILs were derived from and administered to 91 patients with treatment-refractory mismatch repair proficient metastatic gastrointestinal cancers in a schema with lymphodepleting chemotherapy and high-dose interleukin-2 (three cohorts of an ongoing trial). The primary endpoint of this study was the objective response rate as measured using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors 1.0; safety was a descriptive secondary endpoint. In the pilot phase, no clinical responses were observed in 18 patients to bulk, unselected TILs; however, when TILs were screened and selected for neoantigen recognition (SEL-TIL), three responses were seen in 39 patients (7.7% (95% confidence interval (CI): 2.7–20.3)). Based on the high levels of programmed cell death protein 1 in the infused TILs, pembrolizumab was added to the regimen (SEL-TIL + P), and eight objective responses were seen in 34 patients (23.5% (95% CI: 12.4–40.0)). All patients experienced transient severe hematologic toxicities from chemotherapy. Seven (10%) patients required critical care support. Exploratory analyses for laboratory and clinical correlates of response were performed for the SEL-TIL and SEL-TIL + P treatment arms. Response was associated with recognition of an increased number of targeted neoantigens and an increased number of administered CD4+ neoantigen-reactive TILs. The current strategy (SEL-TIL + P) exceeded the parameters of the trial design for patients with colorectal cancer, and an expansion phase is accruing. These results could potentially provide a cell-based treatment in a population not traditionally expected to respond to immunotherapy. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01174121.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Next-generation sequencing data for all samples in this study will be deposited in raw fastq format to the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes under study accession number phs001003. Please contact the corresponding authors for additional data. Upon reasonable request, the corresponding authors will respond within 2 weeks.

Change history

15 April 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03708-5

References

Rosenberg, S. A. et al. Use of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and interleukin-2 in the immunotherapy of patients with metastatic melanoma. A preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 319, 1676–1680 (1988).

Rosenberg, S. A. et al. Durable complete responses in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic melanoma using T-cell transfer immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 4550–4557 (2011).

Goff, S. L. et al. Randomized, prospective evaluation comparing intensity of lymphodepletion before adoptive transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for patients with metastatic melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 2389–2397 (2016).

Sarnaik, A. A. et al. Lifileucel, a tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte therapy, in metastatic melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 39, 2656–2666 (2021).

Rohaan, M. W. et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte therapy or ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 2113–2125 (2022).

Levi, S. T. et al. Neoantigen identification and response to adoptive cell transfer in anti-PD-1 naive and experienced patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 28, 3042–3052 (2022).

Rizvi, N. A. et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science 348, 124–128 (2015).

Samstein, R. M. et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat. Genet. 51, 202–206 (2019).

Marabelle, A. et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol. 21, 1353–1365 (2020).

Ready, N. et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (CheckMate 568): outcomes by programmed death ligand 1 and tumor mutational burden as biomarkers. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, 992–1000 (2019).

Seitter, S. J. et al. Impact of prior treatment on the efficacy of adoptive transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 27, 5289–5298 (2021).

Creelan, B. C. et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte treatment for anti-PD-1-resistant metastatic lung cancer: a phase 1 trial. Nat. Med. 27, 1410–1418 (2021).

Schoenfeld, A. J. et al. Lifileucel, an autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte monotherapy, in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer resistant to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 14, 1389–1402 (2024).

Tran, E. et al. Cancer immunotherapy based on mutation-specific CD4+ T cells in a patient with epithelial cancer. Science 344, 641–645 (2014).

Tran, E. et al. T-cell transfer therapy targeting mutant KRAS in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 2255–2262 (2016).

Zacharakis, N. et al. Immune recognition of somatic mutations leading to complete durable regression in metastatic breast cancer. Nat. Med. 24, 724–730 (2018).

Stevanovic, S. et al. Complete regression of metastatic cervical cancer after treatment with human papillomavirus-targeted tumor-infiltrating T cells. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 1543–1550 (2015).

Amaria, R. et al. Efficacy and safety of autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in recurrent or refractory ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 12, 006822 (2024).

Kim, S. P. et al. Adoptive cellular therapy with autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and T-cell receptor-engineered T cells targeting common p53 neoantigens in human solid tumors. Cancer Immunol. Res. 10, 932–946 (2022).

Parkhurst, M. R. et al. Unique neoantigens arise from somatic mutations in patients with gastrointestinal cancers. Cancer Discov. 9, 1022–1035 (2019).

Zacharakis, N. et al. Breast cancers are immunogenic: immunologic analyses and a phase II pilot clinical trial using mutation-reactive autologous lymphocytes. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 1741–1754 (2022).

Turcotte, S. et al. Phenotype and function of T cells infiltrating visceral metastases from gastrointestinal cancers and melanoma: implications for adoptive cell transfer therapy. J. Immunol. 191, 2217–2225 (2013).

Lowery, F. J. et al. Molecular signatures of antitumor neoantigen-reactive T cells from metastatic human cancers. Science 375, 877–884 (2022).

Krishna, S. et al. Stem-like CD8 T cells mediate response of adoptive cell immunotherapy against human cancer. Science 370, 1328–1334 (2020).

Goodman, A. M. et al. Tumor mutational burden as an independent predictor of response to immunotherapy in diverse cancers. Mol. Cancer Ther. 16, 2598–2608 (2017).

McGranahan, N. et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science 351, 1463–1469 (2016).

Schneider, B. J. et al. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: ASCO guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 39, 4073–4126 (2021).

Parkhurst, M. R. et al. T cells targeting carcinoembryonic antigen can mediate regression of metastatic colorectal cancer but induce severe transient colitis. Mol. Ther. 19, 620–626 (2011).

Johnson, L. A. et al. Gene therapy with human and mouse T-cell receptors mediates cancer regression and targets normal tissues expressing cognate antigen. Blood 114, 535–546 (2009).

Qi, C. et al. Claudin18.2-specific CAR T cells in gastrointestinal cancers: phase 1 trial final results. Nat. Med. 30, 2224–2234 (2024).

Turcotte, S. et al. Art of TIL immunotherapy: SITC’s perspective on demystifying a complex treatment. J. Immunother. Cancer 13, 010207 (2025).

Chesney, J. et al. Efficacy and safety of lifileucel, a one-time autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) cell therapy, in patients with advanced melanoma after progression on immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted therapies: pooled analysis of consecutive cohorts of the C-144-01 study. J. Immunother. Cancer 10, e005755 (2022).

Eng, C. et al. Atezolizumab with or without cobimetinib versus regorafenib in previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (IMblaze370): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 20, 849–861 (2019).

Chen, E. X. et al. Effect of combined immune checkpoint inhibition vs best supportive care alone in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: the Canadian Cancer Trials Group CO.26 study. JAMA Oncol. 6, 831–838 (2020).

Le, D. T. et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science 357, 409–413 (2017).

Kristensen, N. P. et al. Neoantigen-reactive CD8+ T cells affect clinical outcome of adoptive cell therapy with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in melanoma. J. Clin. Invest. 132, e150535 (2022).

Lo, W. et al. Immunologic recognition of a shared p53 mutated neoantigen in a patient with metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 7, 534–543 (2019).

Hall, M. S. et al. Neoantigen-specific CD4+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are potent effectors identified within adoptive cell therapy products for metastatic melanoma patients. J. Immunother. Cancer 11, e007288 (2023).

Espinosa-Carrasco, G. et al. Intratumoral immune triads are required for immunotherapy-mediated elimination of solid tumors. Cancer Cell 42, 1202–1216 (2024).

Prieto, P. A. et al. Enrichment of CD8+ cells from melanoma tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte cultures reveals tumor reactivity for use in adoptive cell therapy. J. Immunother. 33, 547–556 (2010).

Levin, N. et al. Neoantigen-specific stimulation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes enables effective TCR isolation and expansion while preserving stem-like memory phenotypes. J. Immunother. Cancer 12, e008645 (2024).

Barras, D. et al. Response to tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte adoptive therapy is associated with preexisting CD8+ T-myeloid cell networks in melanoma. Sci. Immunol. 9, eadg7995 (2024).

Pelka, K. et al. Spatially organized multicellular immune hubs in human colorectal cancer. Cell 184, 4734–4752 (2021).

Parkhurst, M. et al. Adoptive transfer of personalized neoantigen-reactive TCR-transduced T cells in metastatic colorectal cancer: phase 2 trial interim results. Nat. Med. 30, 2586–2595 (2024).

Deniger, D. C. et al. T-cell responses to TP53 ‘hotspot’ mutations and unique neoantigens expressed by human ovarian cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 5562–5573 (2018).

Dudley, M. E. et al. Generation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte cultures for use in adoptive transfer therapy for melanoma patients. J. Immunother. 26, 332–342 (2003).

Robbins, P. F. et al. Mining exomic sequencing data to identify mutated antigens recognized by adoptively transferred tumor-reactive T cells. Nat. Med. 19, 747–752 (2013).

Parikh, A. Y. et al. Using patient-derived tumor organoids from common epithelial cancers to analyze personalized T-cell responses to neoantigens. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 72, 3149–3162 (2023).

Abate-Daga, D. et al. Expression profiling of TCR-engineered T cells demonstrates overexpression of multiple inhibitory receptors in persisting lymphocytes. Blood 122, 1399–1410 (2013).

Vasimuddin, M., Misra, S., Li, H. & Aluru, S. Efficient architecture-aware acceleration of BWA-MEM for multicore systems. In 2019 IEEE Int. Parallel Distribut. Process. Symp. (IPDPS). https://doi.org/10.1109/IPDPS.2019.00041 (IEEE, 2019).

Van der Auwera, G. A. & OʼConnor, B. D. Genomics in the Cloud: Using Docker, GATK, and WDL in Terra (O’Reilly Media, 2020).

Koboldt, D. C. et al. VarScan: variant detection in massively parallel sequencing of individual and pooled samples. Bioinformatics 25, 2283–2285 (2009).

Kim, S. et al. Strelka2: fast and accurate calling of germline and somatic variants. Nat. Methods 15, 591–594 (2018).

Cibulskis, K. et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 213–219 (2013).

Larson, D. E. et al. SomaticSniper: identification of somatic point mutations in whole genome sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28, 311–317 (2011).

Bray, N. L., Pimentel, H., Melsted, P. & Pachter, L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 525–527 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This study would not have been possible without the collective efforts of Surgery Branch staff and Clinical Center nursing support, including X. Zhao, F. Cobarde, N. Torres, K. Ezhakunnel, D. Komjathy, E. Abecassis, N. Mesa-Diaz, Z. Zheng, A. Berman, K. Borkowski, M. Dawson, R. Salau, M. Rilko, D. Warga, S. Ramirez, S. Chen, B. Zhu, J. Fisher, M. Chaikin, A.-R. Torres, N. Sellers, T Benzine, S. Chatmon, D. White and additional Surgery Branch alumni. This work was primarily supported by funding from the Intramural Research Program, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research with additional support through a collaborative research and development agreement with Iovance Biotherapeutics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L.G., M.R.P., P.F.R., J.C.Y. and S.A.R. conceived of and designed the original and revised clinical study. F.J.L., B.G., M.R.P., T.E.S., M.M.L., S.R., J.J.G., T.D.P., P.F.R., J.C.Y. and S.A.R. developed the methodology. F.J.L., S.L.G., B.G., M.R.P., N.M.R., H.K.H., T.E.S., M.M.L., A.B., A.J.D., V.D., I.S.G., A.M.G., A.A.H., K.J.H., L.M.K., L.L., J.G.R.-W., A.B., S.R., C.D.S., C.D.H., J.M.H., J.J.G., S.S., T.D.P., L.S.M., S.K., P.F.R., N.D.K., M.L.M.K., J.C.Y. and S.A.R. acquired the data (accrued and managed patients, tumor resections, manufactured products, etc.). F.J.L., S.L.G., B.G., M.R.P., N.M.R., J.J.G., S.S., P.F.R., J.C.Y. and S.A.R. analyzed and interpreted the data (statistical analysis, biostatistics and computational analysis). F.J.L., S.L.G., B.G., M.R.P., I.S.G., P.F.R, J.C.Y. and S.A.R. wrote, reviewed and revised the paper. S.L.G., A.J.D., A.M.G., A.A.H., K.J.H., L.M.K., C.D.S., L.S.M., N.D.K., M.M.K., J.C.Y. and S.A.R. were responsible for the clinical care of patients.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Andres Cervantes and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Saheli Sadanand, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 TIL selection process.

a. Schematic of tumor resection, TIL growth, and TIL screening pipeline. Tumors were surgically removed and dissected into small fragments, which were grown in IL-2 for TIL fragment culture expansion. Additional tumor fragments were sequenced by whole exome and RNA-seq. Based on tumor mutation calling, candidate neoepitopes were generated in vitro (25-amino acid peptides or minigene constructs with mutation-encoded amino acid at the center [13th] position). Candidate neoepitopes are expressed by autologous dendritic cells in pools (peptide pools [PP] or tandem minigenes [TMG]). TIL fragment cultures are then co-cultured with these candidate neoepitope-expressing dendritic cells or PDTO if available and TIL demonstrating specific TCR-mediated activation (IFNγ release or induction of cell surface 4-1BB (CD137) or OX40 (CD134) following co-culture were selected for potential treatment. b. Example of TIL screening for tumor 4493. From tumor 4493, 12/24 TIL cultures expanded to numbers sufficient for testing. Based on the corresponding tumor sequencing, 48 candidate neoepitopes were screened in 3 PPs and 3 TMGs. Reactivity was observed against TMG3 (CD8 + TIL exhibiting 4-1BB) and PPs 1 and 2 (CD4 + TIL showing 4-1BB/OX40 induction). TIL fragments selected for treatment are indicated with arrows. Cultures not selected for treatment that appear reactive (for example F6, with ~15% CD8 reactivity vs. TMG3) were of inappropriate phenotype (for example F6 was <20% CD8 or <3% reactive in total). PDTO was not available for this patient. c. Example of TIL infusion product retrospective testing for tumor 4493. Cryopreserved TIL were separated into CD8+ and CD4+ fractions and co-cultured with autologous dendritic cells expressing multiple concentrations of neoantigenic peptides within their ‘selected’ target TMGs and PPs. The peak activation value (4-1BB for CD8, 4-1BB and/or OX40 for CD4) subtracting out vehicle control (DMSO) was considered the specific reactivity value against a neoantigen. Left, TMG3 reactivity was mediated by CD8 + TIL reactive to mutant DOP1A. Center, PP2 reactivity was mediated by CD4 + TIL reactive to mutant ZFP36L1. Right, PP1 reactivity was mediated by CD4 + TIL reactive to mutant PANK4. d. Reactivity calculations for example infusion product 4493 from C. Peak CD8 reactivity value against mutant DOP1A and CD4 reactivity against mutant ZFP36L1 and PANK4 was used to calculate numbers of reactive CD8 (left), CD4 (center), and all TIL (right). e. Overall clinical schema illustrating timing of cyclophosphamide (Cy), fludarabine (F), TIL, interleukin-2 (IL-2), and pembrolizumab (P) when added. f. Partial response of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma liver metastases following treatment with SEL-TIL + P. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pre-treatment (left) and post-treatment (right) liver. Post-treatment images were obtained 5 months after 4493 TIL infusion.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Regression of target tumors in patients receiving selected TIL.

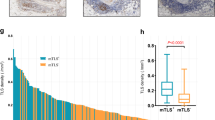

a. Waterfall plot of maximal change from baseline of target tumors per RECIST 1.0 post-TIL infusion for SEL (left, n = 39) and SEL + P (right, n = 34) arms. Bars are colored according to primary tumor histology (Lower GI in blue, upper GI in red, HPB in green). Bars labeled with numbers indicate duration of confirmed partial responses, asterisks indicate clinical non-responders with >30% reduction, hexagons indicate the patients with further imaging in panels b-d, and the caret indicates a non-evaluable patient whose disease progressed prior to first follow-up visit. Underlined values represent previously published case reports14,15 b. Regression of diffuse hepatic metastases in a patient with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Stable hemangioma noted (Hemang). Baseline (left) and six-week follow-up (right) shown. c. Regression of multiple pulmonary nodules and resolution of pleural effusion in a patient with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Baseline (left) and six-week follow-up (right) shown. d. Regression of pulmonary tumors in a patient with colon cancer. Baseline (left) and 10-month evaluation (right) shown. Patient is a non-responder for development of a new brain metastasis at 6 months (not shown).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Transcriptomic analysis of TIL harvest tumors from SEL-TIL + P arm.

a. Volcano plot of DEGs between TIL harvest lesions of responders (n = 8) and non-responders (n = 25). Dotted lines indicate adjusted p-values < 0.05 (Benjamini-Hochberg corrected to adjust for multiple comparisons) and absolute log2FC > 2. Highlighted genes include selected immune-related genes and those from IPA-indicated pathways (Extended Data Fig. 4a). b. Normalized enrichment scores (NES) of significantly enriched hallmark gene sets (nominal p-value < 0.05, GSEA) in TIL harvest lesions from responders (black) or non-responders (white). Gene sets with false discovery rates < 0.3 are included to correct for multiple comparisons. c. Clustering of bulk tumor RNA-seq data by patient (SEL-TIL + P) according to top and bottom 100 response-associated DEGs. Z-scaled gene expression is indicated red to blue, and clinical response to TIL is shown below cluster plots (black for RECIST response, white for non-response). Responder-enriched clusters 1 and 2 show enhanced expression of response-associated genes, while non-responder-enriched clusters 3 and 4 show heightened expression of non-response-associated genes.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) of response-associated DEGs (SEL-TIL + P) and clustering of SEL-TIL tumor RNA.

a. Top 10 response-associated and non-response associated pathways of DEGs within TIL harvest lesions of SEL-TIL + P arm according to IPA. Pathways with highest significant z-scores are shown and ranked by -log10(p-value), with responder-enriched pathways in black and non-responder-enriched pathways in white. IPA-generated p-values are Benjamini-Hochberg corrected to adjust for multiple comparisons b. TIL harvest tumor RNA samples from SEL-TIL group (n = 36 samples) were clustered according to top and bottom 100 response-associated DEGs of SEL-TIL + P group. Patient response to TIL is shown below, with black indicating RECIST response and white indicating non-response to TIL.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table 3

Response-associated tumor DEGs (SEL-TIL + P).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lowery, F.J., Goff, S.L., Gasmi, B. et al. Neoantigen-specific tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in gastrointestinal cancers: a phase 2 trial. Nat Med 31, 1994–2003 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03627-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03627-5