Abstract

Guideline-adherent care is associated with better patient outcomes, but whether this can be achieved by professional education is unclear. Here we conducted a cluster-randomized controlled trial across 70 centers in six countries to understand if a program for the education of healthcare professionals could improve patient-level adherence to clinical practice guidelines on atrial fibrillation (AF). Each center recruited patients with AF seen in routine practice (total N = 1,732), after which the centers were randomized, accounting for baseline guideline adherence to class I and III recommendations from the European Society of Cardiology on stroke prevention and rhythm control. Healthcare professionals in the intervention centers received a 16-week structured educational program with an average of 9 h of online engagement, whereas those at control centers received no additional education beyond standard practice. For the co-primary stroke prevention outcome, guideline adherence was 63.4% and 58.6% at baseline and 67.5% and 60.9% at 6–9-months follow-up for the intervention and control groups, respectively (adjusted risk ratio 1.10; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.97 to 1.24; P = 0.13). For the co-primary rhythm control outcome, guideline adherence was 21.4% and 20.4% at baseline and 33.9% and 22.9% at follow-up for the intervention and control groups, respectively (adjusted risk ratio 1.51; 95% CI 1.04 to 2.18; P = 0.03). The secondary outcome of patient-reported integrated AF management showed a 5.1% improvement in the intervention group compared with the control group (95% CI 1.4% to 8.9%; P = 0.01). Thus, while the education of healthcare professionals improved substantial gaps in implementation for rhythm control, it had no significant effect on stroke prevention. ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT04396418.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Considerable effort and resources are expended globally to educate and train healthcare professionals to improve outcomes for patients1. The effectiveness of these programs is highly variable and dependent on technique, interactivity and subject context2,3. Clinical practice guidelines are widely used around the world to standardize care and provide optimal patient management according to the current evidence base. However, implementation of guideline-adherent care is often challenging, especially in conditions with high patient heterogeneity where delivery of the optimal treatment pathway is dependent on individual clinical factors. One such condition is atrial fibrillation (AF), which is already one of the most common cardiovascular conditions and expected to double in prevalence in the coming decades4,5. There is a substantial risk of morbidity and mortality associated with AF6,7, but this is highly variable and requires an individualized approach and often difficult decision-making on best-practice management8. Guideline-adherent care for anticoagulation therapy in patients with AF9,10 has been associated with lower rates of stroke, bleeding and death11,12,13.

The extent of guideline implementation is challenging to ascertain in observational research although typically thought to be poor, with numerous barriers implicated such as appropriate education14,15,16. Patient education has the potential to reduce serious adverse events and have a positive impact on quality of life in patients with AF17. However, educational interventions directed at healthcare professionals to improve the adherence to cardiovascular guidelines have had limited success18. The Stroke prevention and rhythm control Therapy Evaluation of an Educational Program of the European society of cardiology in a Cluster Randomized trial in patients with Atrial Fibrillation (STEEER-AF) trial was designed to robustly determine real-world adherence to clinical practice guidelines and examine the value of an educational intervention directed to a range of healthcare professionals treating patients with AF19,20. The primary objective was to establish if the addition of concise structured learning for healthcare professionals could improve patient-level adherence to guidelines for stroke prevention and rhythm control compared with standard practice.

Results

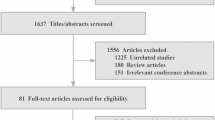

Seventy centers across France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain and the UK were included, with center characteristics summarized in Extended Data Table 1. A total of 1,732 patients with AF were recruited, with average cluster size of 24.7 patients (coefficient of variation in cluster size 0.06) (Fig. 1). The mean age of participants was 68.9 years (s.d. 11.7), with 647 (37.4%) women and similar baseline characteristics between the randomized groups (Table 1). The randomization of centers took place only after participant recruitment had closed (between May 2022 and February 2023), with 35 centers allocated to the intervention and 35 to the control. The minimization algorithm ensured that randomization was balanced within each country for baseline guideline adherence (Extended Data Table 2).

CONSORT diagram for the centers and patients enrolled in the trial. Each center was randomized only after patient recruitment had been completed, aiming for a maximum of 25 patients per center. A 1:1 randomization to intervention (additional education for healthcare professionals) or control (usual approaches to medical education) was performed using a minimization algorithm to account for country and the cluster-level values for the co-primary outcomes at baseline. All centers randomized to the intervention group received the educational program.

Baseline adherence to guidelines

Guideline adherence was evaluated for each individual patient using the pre-published decision tree algorithm20. The observed guideline adherence at baseline to all relevant class I and III European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommendations for stroke prevention overall was 61.0% (intracluster correlation coefficient 0.11). In the intervention group, 548 patients (63.4%) were fully adherent for stroke prevention, with 508 (58.6%) in the control group. For rhythm control, overall guideline adherence at baseline was 21.0% (intracluster correlation coefficient 0.26); there were 185 patients (21.4%) in the intervention group fully adherent and 178 (20.5%) in the control group.

Co-primary outcomes

The median time between randomization and completion of the follow-up electronic case report forms (eCRF) was 7.7 months (interquartile range (IQR) 5.9–8.8 months). For stroke prevention at follow-up, guideline adherence increased to 516 patients (67.5%) in the intervention group and 471 (60.9%) for control (Table 2 and Fig. 2). The risk ratio for intervention versus control after adjusting for baseline values, country and clustering by center was 1.10 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.97 to 1.24; P = 0.13). The corresponding adjusted risk difference was 6.0% (95% CI −1.5% to 13.4%; P = 0.12). For rhythm control at follow-up, guideline adherence increased to 259 patients (33.9%) in the intervention group and 177 (22.9%) for control. The adjusted risk ratio for intervention versus control was significant at 1.51 (95% CI 1.04 to 2.18; P = 0.03), with adjusted risk difference 11.2% (95% CI 1.6 to 20.7; P = 0.02).

Outcomes are presented as a risk ratio or adjusted mean difference for intervention versus control, with circles for point estimates and capped lines for the 95% CI adjusted for baseline values, country and clustering by center. For each outcome, absolute values are indicated at baseline and follow-up for each of the groups. The shaded area indicates the co-primary trial outcomes.

Secondary outcomes

Prescriptions of oral anticoagulation according to class I and class I/IIa indications were high (94% and 92% at baseline) and not impacted by the intervention (risk ratio 1.02, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.05; P = 0.26 and 1.01, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.05; P = 0.40, respectively; Table 2 and Fig. 2). The proportions of class I and III stroke prevention and rhythm control guidelines with adherence were consistent with the co-primary outcomes (adjusted mean difference in proportions of 3.2% for stroke prevention, 95% CI −0.1% to 6.5%; P = 0.06 and 5.8% for rhythm control, 95% CI 0.4% to 11.3%; P = 0.04). The proportion of applicable patients failing at each point in the guideline decision tree was variable, with key factors for both stroke prevention (Extended Data Table 3) and rhythm control (Extended Data Table 4) being appropriate evaluation and patient indication(s) for the therapeutic approach. Patients in the intervention group reported a significant 5.1% improvement over control in the proportion attaining integrated AF management (95% CI 1.4% to 8.9%; P = 0.01). There were no differences between groups in patient-reported quality of life.

Process outcomes

Learners spent a median of 9.2 h (IQR 6.4–13.4 h) on the online platform (Extended Data Table 5), with a high level of involvement with required reading (mean 94.8%, s.d. 9.7) and with their commitment to change local practice (97.8% implemented). The expert trainer was engaged by 158 of 195 learners (81.0%). The proportion of correct answers to multiple-choice questions increased with the intervention, from a mean of 65.2% before the education (s.d. 18.3%) to 72.0% after (s.d. 19.9%) (post-hoc P < 0.001).

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

Exploratory analyses indicated consistent effects for the co-primary outcomes across subgroups for patient age and baseline thromboembolic risk (Fig. 3). Effects were noted to vary by country for stroke prevention (P interaction = 0.01; Extended Data Table 6) and sex for rhythm control (Pinteraction = 0.01; Extended Data Table 7). The sensitivity analysis confirmed robust findings for both co-primary outcomes (Extended Data Fig. 1).

Discussion

STEEER-AF demonstrates that adherence to the ‘must-do’ and ‘must-do not’ guideline recommendations in routine practice is poor, in particular the implementation of rhythm control in patients with AF. The educational intervention for healthcare professionals in the STEEER-AF trial resulted in a 51% relative increase (11.2% absolute increase) in patient-level adherence to recommendations for rhythm management. This benefit resulted from a relatively short and targeted educational program in addition to, and compared against, existing approaches for continued medical education. We saw no significant difference for guideline adherence to recommendations on the prevention of stroke and thromboembolism in AF.

Findings for the secondary outcomes were consistent with the co-primary results and help explain the divergence in results of STEEER-AF across the two components of AF care. The prescription of oral anticoagulants, which form the basis of stroke prevention in the majority of patients, was high. A key patient-reported secondary outcome demonstrated the intervention improved integration of care, with education, shared decision-making and the empowerment of patients being important facets of delivering optimal and individualized rhythm control.

Overall guideline adherence in the STEEER-AF trial was substantially lower than anticipated from prior observational research, where self-reporting can introduce response bias21. Our study suggests the need for a reappraisal of strategies to improve the delivery of patient care and enhance guideline adoption by guideline writers, professional associations, medical educators and policy makers. Prior evidence for improving guideline-adherent care is largely restricted to the use of oral anticoagulation in patients with AF, including a cluster trial which demonstrated higher rates of anticoagulant prescription with education compared with usual care (odds ratio 3.28, 95% CI 1.67 to 6.44), and lower rates of the secondary outcome of incident stoke in the intervention group (hazard ratio 0.48, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.99)22. Of note, that trial was performed in Argentina, Brazil, China, India and Romania, with 68% of patients prescribed an oral anticoagulant at baseline. On the basis of the findings from STEEER-AF and these other studies, implementing approaches to guideline-adherent management is likely to require focused education that is tailored not only to a specific delivery gap, but also the needs of the individual healthcare professional in the context of the local healthcare environment. Although we observed an improvement in rhythm control adherence, additional approaches are clearly needed to tailor education for patients and healthcare professionals, further improving guideline adherence and patient outcomes. A trial of shared decision-making did not identify any benefit for anticoagulation use in AF or related safety endpoints23, although it could be argued that shared care is dependent on adequate levels of education for both patients and healthcare staff.

This trial was designed to test the value of education specifically for healthcare professionals, as prior trials have already demonstrated that patient education, with the right approach and format, can yield benefits for patients with AF17,24. We accounted for a range of inherent biases that are common when assessing the value of an educational intervention. Recruitment of participants at each site was completed before randomization could take place, and extraction of the clinical pathway for each patient was determined objectively rather than from the healthcare professional involved. Any imbalance in randomization was minimized using the cluster-level adherence of the co-primary outcomes calculated at baseline, and the algorithm to determine guideline adherence was pre-defined but not disclosed. Although we were unable to blind healthcare professionals to the randomized allocation at their center, all coordinating staff were kept blinded. Care was taken to avoid any contamination of trial groups by geographically dispersing sites across each country. The enrolled participants were a good reflection of patients with AF seen in real-world cohort studies25,26,27. Despite considerable external events (such as the coronavirus pandemic, which precluded in-person training of healthcare professionals20), there was good engagement with the bespoke online educational platform that was specifically developed to achieve sustainable behavioral change, supported by national trained experts.

The findings of STEEER-AF on targeted education for healthcare professionals, combined with past research on targeted education of patients, would suggest an important opportunity to achieve clinical and societal benefit through scalable multifactorial interventions. These approaches need to be part of broader quality improvement efforts that are ongoing in local environments, national policy-making and also on the international level (for example, World Health Organization Quality of Care in line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals; the European Commission’s European Education Area initiative; and various strategies on education and quality improvement by the Association of American Medical Colleges).

There are limitations that warrant consideration. First, the trial was established to ascertain the value of additional education; hence both intervention and control groups could engage in whatever usual approaches were available to meet their educational needs. As a pragmatic trial embedded within clinical practice, it was not possible to determine or account for varying levels of education within or across the six countries20. However, all the countries involved are members of the ESC and European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), which have the same core curriculum for cardiology that includes AF28. Second, the co-primary outcomes were focused on determining adherence to class I and III recommendations (that is, where there is no dispute that treatments are either effective or harmful). This leaves out many areas of routine practice that are important to patient care. Although the ESC guidelines have contribution from the national cardiac societies in each country, there can be different applications of best practice locally. The STEEER-AF was deployed across 70 centers in six countries so that regional or national differences in implementation were accounted for by design. Third, the trial was conducted in the European secondary care setting, and the findings may not apply to primary care, lower-income areas or environments with a different approach to professional development. Although care was taken to engage a broad range of centers within each country, these sites did agree to participate, which may indicate an existing interest in quality improvement. The trial was powered to detect clinically relevant changes in guideline adherence within the first year, rather than clinical outcomes, which will be explored in future reports. Finally, the sample size assumptions deviated from actuality (lower baseline adherence using our objective trial assessment than expected from available observational data), and so the trial may be underpowered to detect the anticipated differences in stroke prevention management.

In summary, the STEEER-AF trial showed that guideline adherence in patients with AF is poor. Focused education for healthcare professionals did not demonstrate positive effects on guideline-adherent care for both co-primary outcomes. Improvement was noted in rhythm control where guideline implementation was particularly low, but with no significant effect on recommendations addressing stroke prevention where anticoagulation use was near-optimal.

Methods

Trial design and oversight

STEEER-AF is an international, pragmatic, two parallel group, cluster-randomized controlled trial, supported in its design by a patient and public involvement team19,20. The full protocol is available in the additional files (no changes after trial commencement). A cluster design was the most suitable approach for testing the educational program for healthcare professionals, as effect contamination could occur with individual patient-level randomization. The trial was sponsored by the ESC, with contribution from the EHRA and ESC Council on Stroke. A trial management group and trial steering committee directed the program, with oversight provided by an independent data monitoring committee and strategic oversight committee (Extended Data Table 8).

Ethics and inclusion statement

The trial was approved by ethical review committees in each country and local research governance authorities for each center. A patient and public involvement team aided with the design of the concept and drafting of patient-facing material to improve inclusivity. The trial was prospectively registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04396418).

Participating centers, investigators and patients

The cluster-level selection criteria were a site that agreed to participation, enrollment and follow-up of patients and randomization of the site to the intervention or control for healthcare practitioners at that center. A national coordinator for each country was tasked with engaging a broad range of centers in their country that treat patients with AF and were representative of usual care, and selected a local principal investigator (PI) for each site. Healthcare professionals were nominated by the PI from across different specialties within each center to act as investigators, including trainee and experienced doctors, nurses and allied health professionals, with no more than a third of investigators seeing patients with AF on a daily basis. Each investigator recruited patients who were under their routine clinical care, with a maximum of 25 patients per center. Participants required a clinical diagnosis of AF and the ability to provide written informed consent. Patient-level exclusion criteria were age under 18 years, pregnancy or planning to be pregnant, breastfeeding at the time of consent, participation in another clinical trial of an investigational medicinal product or device and life expectancy of less than 2 years. Participants were followed up in routine practice by the same investigator at 6–9 months after each center was randomized. Where that was not possible (for example, the healthcare professional had left that institution), follow-up was performed by another investigator from that center.

Randomization and masking

Centers were randomized only after they had finished participant recruitment and fully completed baseline eCRF, managed by an independent contract research organization (Soladis). To provide objective assessment of the clinical care received, the eCRF was completed by the PI who was not involved in the care pathway for recruited participants. The eCRF was completed after the interaction between patient and investigator using all available clinical and/or electronic documentation. The PI received queries for any missing elements on the eCRF forms. Algorithms were used to objectively determine guideline adherence at the level of each patient. These algorithms were finalized and approved before the first randomization and are available in an open-access publication (https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euae178)20.

The algorithms were applied to the eCRF data for each participant. Guideline adherence was not disclosed to the PI or investigators to avoid influencing follow-up. Randomization was performed by the Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit (University of Birmingham), with a 1:1 ratio to intervention or control using a minimization algorithm to ensure balance by (1) country, (2) cluster-specific mean for class I and III guideline adherence to stroke prevention at baseline (<70 and ≥70%) and (3) cluster-specific mean for class I and III guideline adherence to rhythm control at baseline (<50 and ≥50%). The randomized allocation was performed by the trial statistician blinded to the identity of the centers. Owing to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind investigators to the randomized allocation. The trial steering committee were blinded to the randomized allocation of centers during the entire trial.

Intervention and control

The educational intervention for healthcare professionals was targeted toward stroke prevention, rhythm control and integrated care in AF, with learning modules translated to the language for each participating country. Investigators from centers randomized to the intervention group were enrolled in an additional educational program lasting 16 weeks, primarily consisting of online resources. The intervention was designed by the ESC and EHRA, taking advantage of decades of work in methods applied to better educate healthcare professionals1, and utilizing educational theory and learning frameworks to achieve sustainable behavioral change29. The educational intervention was developed with the assistance of an independent medical education agency (Liberum IME), with further details published previously20.

The web-based platform included course materials, interaction with peers, case-based learning, videos and additional reading (providing direct educational benefit). Learners were supported by an expert trainer from that country that assisted with case-based examples of appropriate guideline-adherent care, and helped them to generate a ‘commitment to change’ plan that could be implemented locally to improve the management of patients with AF (indirect benefits from the educational program).

Centers randomized to the control group did not receive the additional educational intervention, but investigators were able to continue any existing healthcare professional development.

Outcomes

Full details on the outcomes are presented in the protocol. The co-primary outcomes were guideline adherence for stroke prevention and rhythm control on the basis of class I and III ESC recommendations from the 2016 and 2020 guidelines on the management of AF9,10. The prespecified secondary outcomes were the proportion of guidelines with adherence for stroke prevention and rhythm control, and the proportion of participants receiving anticoagulation according to class I and class I/IIa indications. The key patient-reported outcome was a score evaluating eight domains of integrated AF management, completed by the patient after their consultation with the investigator. Patient-reported quality of life was determined using the EuroQol EQ-5D-5L questionnaire (index values and visual analog scale). Process outcomes in the intervention group addressed the fidelity of the educational program. Ongoing follow-up is in process to collect future clinical outcomes.

Sample size

Sample size calculations for the stroke prevention co-primary outcome assumed that 80% of control patients expected to receive guideline-adherent care based on available observational studies30,31. A relative increase of 10% was considered clinically relevant (absolute increase from 80% to 88%). For this co-primary outcome, power was 85% based on an intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.04 (refs. 22,32), two-sided alpha 0.05, cluster size of 25 patients, coefficient of variation in cluster size 0.20, 70 clusters and 10% loss of patients to follow-up. For the rhythm control co-primary outcome, estimates of guideline-adherent care for rhythm control in the control group were 50% (refs. 30,33). Using the same assumptions as the stroke prevention co-primary outcome, the power to detect an absolute increase from 50% to 61% was 85%.

Statistical analysis

A statistical analysis plan was finalized and approved before unlocking the trial database (see additional file). All analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle (according to the randomized allocation). The primary comparison was between the centers (clusters) randomized to the intervention group and those randomized to the control group. All model-based analyses were adjusted for minimization criteria (country and baseline guideline adherence for stroke prevention and rhythm control), the baseline of that variable (where appropriate) and clustering for center. All analyses were performed on patient-level data and used patient-level covariate adjustments. For each of the co-primary outcomes, we fitted a generalized linear mixed model using the binomial distribution and logit link (with robust standard error), followed by marginal standardization to estimate the risk ratio and risk difference. Type I error control is not required for co-primary endpoints34. Statistical analyses for the co-primary outcomes were double-coded by an independent statistician in a separate statistical package (Stata; StataCorp) to the analyses conducted by the senior statistician (SAS; SAS Institute). Prespecified subgroup analyses for the co-primary outcomes were the minimization variables and participant age, sex and CHA2DS2-VASc score at baseline (with 2 points for age ≥75 years and prior stroke, transient ischemic attack or systematic embolus, and 1 point for chronic heart failure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, vascular disease, age ≥65 years or female sex). An additional planned subgroup analysis according to the modified EHRA symptom classification score was not pursued owing to missing data for this variable. Effects within these subgroups were examined by including the relevant subgroup by intervention interaction term. To examine the possible impact of any missing data on the co-primary outcome results, a prespecified sensitivity analysis explored whether missing outcomes were ‘missing not at random’ using a tipping point approach. Secondary outcomes with binary data were analyzed using the same methods as described for the co-primary outcomes, and differences in proportions were analyzed using a fractional regression model with logit link and cluster-robust standard errors. Secondary outcomes with continuous data were analyzed using mixed effects linear regression to estimate the adjusted mean difference.

Role of the funding source

The ESC and EHRA (not-for-profit professional organizations) contributed to the study design and data collection. The external funders provided educational grants to the ESC and had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report.

Reporting frameworks

The study is reported according to the cluster randomized trial extension of the CONSORT checklist (see additional file).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Anonymized summary data will be made available for noncommercial purposes on request to the corresponding author, after completion and publication of clinical follow-up and secondary paper (D.K.; d.kotecha@bham.ac.uk; 90-day response time for decisions following review by the STEEER-AF trial management group).

References

Kotecha, D. et al. Roadmap for cardiovascular education across the European Society of Cardiology: inspiring better knowledge and skills, now and for the future. Eur. Heart J. 40, 1728–1738 (2019).

Dunleavy, G. et al. Mobile digital education for health professions: systematic review and meta-analysis by the digital health education collaboration. J. Med. Internet Res. 21, e12937 (2019).

Cervero, R. M. & Gaines, J. K. The impact of CME on physician performance and patient health outcomes: an updated synthesis of systematic reviews. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 35, 131–138 (2015).

Lippi, G., Sanchis-Gomar, F. & Cervellin, G. Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: an increasing epidemic and public health challenge. Int. J. Stroke 16, 217–221 (2021).

Lane, D. A., Skjoth, F., Lip, G. Y. H., Larsen, T. B. & Kotecha, D. Temporal trends in incidence, prevalence, and mortality of atrial fibrillation in primary care. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 6, e005155 (2017).

Mobley, A. R. et al. Thromboembolic events and vascular dementia in patients with atrial fibrillation and low apparent stroke risk. Nat. Med. 30, 2288–2294 (2024).

Meyre, P. et al. Risk of hospital admissions in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can. J. Cardiol. 35, 1332–1343 (2019).

Van Gelder, I. C. et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. 45, 3314–3414 (2024).

Kirchhof, P. et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Europace 18, 1609–1678 (2016).

Hindricks, G. et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): the task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 42, 373–498 (2021).

Nieuwlaat, R. et al. Guideline-adherent antithrombotic treatment is associated with improved outcomes compared with undertreatment in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation. The Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Am. Heart J. 153, 1006–1012 (2007).

Lip, G. Y. et al. Improved outcomes with European Society of Cardiology guideline-adherent antithrombotic treatment in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the EORP-AF General Pilot Registry. Europace 17, 1777–1786 (2015).

Proietti, M. et al. Adherence to antithrombotic therapy guidelines improves mortality among elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: insights from the REPOSI study. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 105, 912–920 (2016).

Fischer, F., Lange, K., Klose, K., Greiner, W. & Kraemer, A. Barriers and strategies in guideline implementation—a scoping review. Healthc. 4, 36 (2016).

Glauser, T. A., Barnes, J., Nevins, H. & Cerenzia, W. The educational needs of clinicians regarding anticoagulation therapy for prevention of thromboembolism and stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am. J. Med. Qual. 31, 38–46 (2016).

Heidbuchel, H. et al. Major knowledge gaps and system barriers to guideline implementation among European physicians treating patients with atrial fibrillation: a European Society of Cardiology international educational needs assessment. Europace 20, 1919–1928 (2018).

Palm, P. et al. Educational interventions to improve outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation—a systematic review. Int J. Clin. Pr. 74, e13629 (2020).

Jeffery, R. A. et al. Interventions to improve adherence to cardiovascular disease guidelines: a systematic review. BMC Fam. Pract. 16, 147 (2015).

Bunting, K. V., Van Gelder, I. C. & Kotecha, D. STEEER-AF: a cluster-randomized education trial from the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 41, 1952–1954 (2020).

Sterlinski, M. et al. Design and deployment of the STEEER-AF trial to evaluate and improve guideline adherence: a cluster-randomized trial by the European Society of Cardiology and European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace 26, euae178 (2024).

Althubaiti, A. Information bias in health research: definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 9, 211–217 (2016).

Vinereanu, D. et al. A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment with oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation (IMPACT-AF): an international, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 390, 1737–1746 (2017).

Noseworthy, P. A. et al. Effect of shared decision-making for stroke prevention on treatment adherence and safety outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 11, e023048 (2022).

Sporn, Z. A., Berman, A. N., Daly, D. & Wasfy, J. H. Improving guideline-based anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation: a systematic literature review of prospective trials. Heart Rhythm 20, 69–75 (2023).

Chiang, C. E. et al. Distribution and risk profile of paroxysmal, persistent, and permanent atrial fibrillation in routine clinical practice: insight from the real-life global survey evaluating patients with atrial fibrillation international registry. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 5, 632–639 (2012).

Potpara, T. S. et al. Cohort profile: the ESC EURObservational Research Programme Atrial Fibrillation III (AF III) Registry. Eur. Heart J. Qual. Care Clin. Outcomes 7, 229–237 (2021).

Proietti, M. et al. Real-world applicability and impact of early rhythm control for European patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the ESC-EHRA EORP-AF Long-Term General Registry. Clin. Res Cardiol. 111, 70–84 (2022).

Tanner, F. C. et al. ESC core curriculum for the cardiologist. Eur. Heart J. 41, 3605–3692 (2020).

Kotecha, D. et al. European Society of Cardiology smartphone and tablet applications for patients with atrial fibrillation and their health care providers. Europace 20, 225–233 (2018).

Kirchhof, P. et al. Management of atrial fibrillation in seven European countries after the publication of the 2010 ESC Guidelines on atrial fibrillation: primary results of the PREvention oF thromboemolic events–European Registry in Atrial Fibrillation (PREFER in AF). Europace 16, 6–14 (2014).

Lip, G. Y. et al. Prognosis and treatment of atrial fibrillation patients by European cardiologists: one year follow-up of the EURObservational Research Programme-Atrial Fibrillation General Registry Pilot Phase (EORP-AF Pilot registry). Eur. Heart J. 35, 3365–3376 (2014).

Campbell, M. K., Fayers, P. M. & Grimshaw, J. M. Determinants of the intracluster correlation coefficient in cluster randomized trials: the case of implementation research. Clin. Trials 2, 99–107 (2005).

Schnabel, R. B. et al. Gender differences in clinical presentation and 1-year outcomes in atrial fibrillation. Heart 103, 1024–1030 (2017).

Hamasaki, T., Evans, S. R. & Asakura, K. Design, data monitoring, and analysis of clinical trials with co-primary endpoints: a review. J. Biopharm. Stat. 28, 28–51 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The STEEER-AF was funded by the ESC and EHRA and supported by educational grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS/Pfizer Alliance, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo and Boston Scientific (grant no. not applicable; D.K.). Additional funding was provided by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Center, Oxford, UK (grant no. not applicable; D.K.) and the Birmingham British Heart Foundation Accelerator, Birmingham, UK (grant no. not applicable; K.V.B.). Trial staff at the coordinating academic center were supported by the NIHR Birmingham Biomedical Research Center, Birmingham, UK (grant no. NIHR203326; D.K.). The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not represent any of the listed organizations. We are grateful to the thousands of individuals (patients, national leaders, PIs, investigators and other staff) supporting the STEEER-AF trial centrally (Extended Data Table 8) and across the 70 centers (Extended Data Table 9), as well as the ESC registries project management team.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Statistical analysis was performed by S.M. and Y.S., who had full access to the data and verified its integrity. The manuscript was drafted by D.K. and S.M. All other principal authors were members of the trial steering committee and edited the manuscript for intellectual content. D.K. and I.C.v.G. were the chief investigators and were responsible for the decision to submit. See Extended Data Tables 8 and 9 for all other contributions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All principal authors have completed the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) uniform disclosure form. D.K. declares support for the present manuscript as follows: ESC supported by educational grants from Boehringer Ingelheim/BMS-Pfizer Alliance/Bayer/Daiichi Sankyo/Boston Scientific, the NIHR/University of Oxford Biomedical Research Center and British Heart Foundation (BHF)/University of Birmingham Accelerator Award (STEEER-AF); grants or contracts from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR; NIHR130280 DaRe2THINK; NIHR132974 D2T-NeuroVascular; NIHR203326 Biomedical Research Center); British Heart Foundation (AA/18/2/34218 and FS/CDRF/21/21032); EU/EFPIA Innovative Medicines Initiative (BigData@Heart 116074); EU Horizon and UKRI (HYPERMARKER 101095480); UK National Health Service—Data for R&D—Subnational Secure Data Environment program (West Midlands); UK Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Regulators Pioneer Fund; Cook and Wolstenholme Charitable Trust; Bayer; Amomed; Protherics Medicines Development; and consulting fees from Bayer, Amomed, Protherics Medicines Development; monitoring board or advisory board for ESC (Chair of 2024 Atrial Fibrillation Guidelines; no payments). K.V.B. declares grants from the BHF (Career Development Research Fellowship for Nurses and Healthcare Professionals—S/CDRF/21/21032); role in other board, society, committee or advocacy groups as member of the British Society of Echocardiography education committee (no payments); and ESC (Coordinator of 2024 Atrial Fibrillation Guidelines; no payments). P.S. declares grants or contracts from Boston, ImriCor and CVRx and participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Abbott, Medtronic and Biosense. M.S. declares grants or contracts from Biotronik, HammerMed and Medtronic; consulting fees from Abbott, Biotronik, HammerMed and Medtronic; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Biotronik, Pfizer, Medtronic, Zoll and Novartis; participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Novartis, Medtronic and Impulse Dynamics; leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group (EHRA Advocacy and Quality Improvement Committee 2022–2024; no payments). L.M. declares research grants paid to his institution from Abbott Medical, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, J&J and Biotronik; consulting fees from Abbott Medical, Medtronic, Boston Scientific and J&J; payment or honoraria for lectures from Abbott Medical, Medtronic, Boston Scientific and J&J; payment for expert testimony and support for attending meetings and/or travel from Abbott Medical, Medtronic and Boston Scientific; participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Medtronic and Boston Scientific; stock or stock options with Stockholder of Galgo Medical, S.L. E.G. declares grants or contracts from Consejo Superior de Deportes (Spanish Culture and Sports Ministry; reference EXP_75119), Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (FIS)—Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities; reference PI22/00953) and H2020-MSCA-ITN-2019 program (local PI; grant agreement 860974). S.B. declares consulting fees from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Microport and Zoll. G.B. declares speakers’ fees from Bayer, Boston, Daiichi Sankyo, Sanofi and Janssen. C.P.G. declares grants or contracts from the Alan Turing Institute, British Heart Foundation, NIHR, Horizon 2020, Abbott Diabetes Bristol-Myers Squibb and ESC; consulting fees from AI Nexus, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehrinher Ingleheim, CardioMatics Chiesi, Daiichi Sankyo, GPRI Research B.V., Menarini, Novartis, iRhythm, Organon and The Phoenix Group; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, Menarini, Novartis, Raisio Group, Wondr Medical and Zydus; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Astra Zeneca; participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for the DANBLCOK trial and the TARGET CTCA trial; leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy groups (Deputy Editor: EHJ Quality of Care and Clinical Outcomes, NICE Indicator Advisory Committee, Chair ESC Quality Indicator Committee); stock or stock options in CardioMatics; receipt of equipment, materials, drugs, medical writing, gifts or other services from Kosmos device. T.J.R.D.P. declares consulting fees and payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations paid to institutions from Adagio Medical, Volta Medical, Boston Scientific and J&J. I.C.v.G. declares consulting fees from Bayer; participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for the PVI SHAM trial; and leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group (Treasurer EHRA; Chair of 2024 Atrial Fibrillation Guidelines; no payments). All other principal authors have nothing to disclose (S.M., K.R., Y.S. and C.v.D.). All consortium authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form. T.D. declares payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Biosense for lecture honoraria and Abbott Educational for lecture honoraria; consulting fees from Biotronik, Educational grant to himself; participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board from Boston scientific, clinical event committee—studies; leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group (German Cardiology Society, Certification committee; EHRA, National society committee; HRS, Digital Health committee). B.G.-M. declares consulting fees from Biotronik, Medtronic, Boston Sc and Microport; participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for BEAT AF Study and STOP DRUG Study (no payments). M.L. declares consulting fees from Abbott; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Boston Scientific; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Boston Scientific and Microport. A. Mobley declares other financial or nonfinancial interests (role is funded by the Cook and Wolstenholme Charitable Trust and the EU-Horizon and UKRI HYPERMARKER grant 101095480). T.R. declares grants or contracts from the NIHR (senior investigator); leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group for the Stroke Association (trustee until October 2023) and the British and Irish Association of Stroke Physicians (president until December 2021). E.M. declares research grants from Abbott, Biotronik, Boston, Scientific, Medtronic, MicroPort and Zoll; consulting fees from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Zoll and Abbott; and payment or honoraria from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Zoll and Abbott. P. Baudinaud declares consulting fees from Medtronic, Abbott and Boston Scientific; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from IMPLICITY; and participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Medtronic. S.K. declares payment or honoraria (ESC; payment for participation as a trainer). U.R. declares grants or contracts from Bayer (research grant to the institution); consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Sanofi; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from medpoint, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS / Lilly and Pfizer. M. Proietti declares other financial or nonfinancial interests (Italian national leader of the AFFIRMO project; EU Horizon 899871). S.T. declares grants or contracts (ESC: payment for participation as a trainer); payment or honoraria for lectures from Abbott, Boston Scientific and Astra Zeneca; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Boston Scientific (Congresses: EHRA 2022, EHRA 2023, ESC 2023). P. Buchta declares consulting fees (ESC); payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Johnson & Johnso; honorarium for lectures/educational training from Abbott and EP Proctor fee; and support for attending meetings and/or travel (EHRA, EHRA Congress Grant). I.R.L. declares consulting fees from Abbott Medical, Biosense Webster and Boston Scientific; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Abbott Medical, Biosense Webster and Boston Scientific; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Abbott Medical, Biosense Webster and Boston Scientific. D.T. declares honoraria from Abbott and Medtronic. A.S. declares consulting fees from Astra Zeneca, Rhythm AI and Reachora; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Abbott Medical; and support for attending meetings and/or travel from Biosense Webster. O.P. declares consulting fees from BMS Pfizer, Abbott and Zoll Medical; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from BMS Pfizer and Abbott; and leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group, paid or unpaid from the French Society Cardiology as a board member and EHRA as a member of the NCS committee. C.D.C. declares grants or contracts paid to the institution (research grant from the French Federation of Cardiology); royalties or licenses paid to the institution (license shared with Biosense Webster); honoraria from Biosense Webster, Abbott and Boston Scientific; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Biosense Webster; travel costs from Biosense Webster and Abbott; and patents planned, issued or pending (patent being used by Biosense Webster, payment to institution; two other patents planned). M.D.G. declares payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Abbott and Medtronic. E.G. declares consulting fees from Boston, Medtronic, Microport and Biotronik; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Microport and Boston; participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Boston; and leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group, unpaid (Vice president groupe de rythmologie et stimulation cardiaque SFC). F.S. declares speaker fees from Abbott, Biosense, Webster, Boston Scientific, Medtronic and Microport; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Abbott, Biosense, Webster, Boston Scientific and Medtronic. C.G. declares consulting fees from Pfizer and Medtronic; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Abbott and Boston Scientific. S.W. declares grants outside the submitted work from Abbott and Boston; consulting fees from Abbott and Boston; speakers bureau from Abbott and Boston (BMS); and participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board (BSCI Fellow ship, Abbott EICP). M. Borlich declares consulting fees from Biosense Webster; speakers honoraria from Novartis and Bayer; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Boston Scientific and the Boston Fellowship. A. Metzner declares consulting fees from Medtronic, Biosense Webster and Boston Scientific; payment or honoraria for lectures from Medtronic, Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, EPD-Philips and Lifetech; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Medtronic, Biosense Webster and Bostin Scientific. H.-H.E. declares grants or contracts from Medtronic and ESC; financial support from Abbot Medical GmbH, Amgen GmbH, Astra Zeneca, Bayer Vital GmbH, Biotronik, Lilly Deutschland GmbH, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. KG, Boston scientific Medizintechnik GmbH, Bristol-Myers Squibb GmbH & Co.KGAA, Daiichi-Sankyo Deutschland GmbH, Medic Plus GmbH, Micro Port GmbH, Medtronic GmbH, Novartis Pharma GmbH, Sanofi–Aventis, Servier Deutschland GmbH, Trommsdorff GmbH & Co. KG and Zoll CMS GmbH; research grant from Medtronic; and payment for presentation from Biotronik. D.D. declares research grants to the institution from CVRx, Roche; consulting fees from Abbott, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myer Squibbs, Medtronic, Pfizer and Sanofi; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Abbott, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Biotronik, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myer Squibbs, CVRx, Medtronic, Pfizer, Sanofi and Zoll; participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board from Cardiomatics, Medtronic and Edwards; leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group, unpaid (Chair of the EHRA digital and e-communication committee). P.N. declares grants or contracts from Abbott, Amicus, Cardiac Dimensions, Daiichi, Chiesi, Idorsia, Sanofi and Takeda; consulting fees from Abbott, Amicus, Cardiac Dimensions, Daiichi, Chiesi, Idorsia, Sanofi and Takeda; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Abbott, Amicus, Cardiac Dimensions, Daiichi, Chiesi, Idorsia, Sanofi and Takeda; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Abbott, Amicus, Cardiac Dimensions, Daiichi, Chiesi, Idorsia, Sanofi and Takeda. R.R.T. declares consulting fees from Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Biosense Webster and Abbott Medical; speaker fees from Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Biosense Webster, Abbott Medical and Lifetech; and research grants from Abbott, Biosense Webster and Lifetech. M. Bertini declares payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Medtronic, Biotronik, Abbott, Microport, Boston,Bayer, Boherningher, Daiichi and Pfizer. S.F. declares grants or contracts (ESC). W.K.G. declares grants or contracts (ESC); payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Biotronik and the ‘Akademia Elektroterapii’ Journal; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Biotronik, Abbott and Medtronic. F.B. declares grants or contracts from Boston Scientific, investigator initiated research—payment to the institution. J.O. declares payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events and support for attending meetings. J.L.M. declares payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Abbott (institution), Milestone Pharmaceuticals (institution), Biotronik (personal) AstraZeneca (institution), Microport (personal) and Zoll (personal); personal support for attending meetings and/or travel from Bayer (personal), Zoll (personal); personal participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board from Medtronic and Sanofi. N.R.-G. declares research and teaching grants at the Vall d’Hebron Hospital Arrhythmia Unit; Consulting fees from Abbott, Medtronic, Boston Scientific and Johnson & Johnson; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Abbott and Medtronic; payment for expert testimony from Abbott; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Abbott, Medtronic, Boston Scientific and Johnson & Johnson; leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group from the Ritmo Society Accreditation Committee and Spanish Cardiology Society. E.T. declares grants or contracts (speakers’ bureau/ honoraria/research grants; fellowship support from Abbot, Biotronik and Medtronic); consulting fees from Abbott and Biotronik; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events and support for attending meetings and/ or travel and Abbott, Biotronik and Medtronic. F.S.N. declares grants or contracts from the British Heart Foundation (research grant funding), the National Institute for Health Research (research grant funding) and Medical Research Council (research grant funding). M.J.L. declares payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Bisosense-Webster; fees for proctoring cases and lectures; support for attending meetings and/or travel paid to the institution (educational grant to attend conference for Medtronic); unpaid leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group (Member of specialized services device program for NHS England; Monitor new technologies in cardiac rhythm management; Member of NICOR—Cardiac Rhythm—Domain Expert Group). M.F. declares grants or contracts from Barts NIHR (BRC award), Abbott Ltd (SAS AF study), Medtronic Ltd (ORBICA-AF Study), Barts Charity and Minature Robotics for PCI; consulting fees from Abbott, Medtronic, CathVision, Boston Scientific and Arta Health; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Medtronic Ltd, Abbott Ltd, Biosense Webster and Johnson & Johnson; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Abbott, Medtronic and Boston Scientific; patents planned, issued or pending (Rhythm AI Ltd, Echopoint Medical Ltd); leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group (Co-chair EHRA Certification Committee); stock or stock options in Rhythm AI Ltd, Echopoint Medical Ltd. and Epicardio Ltd. H.H. declares grants or contracts from Universities of Hasselt and Antwerp, Abbott, Medtronic, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo and Pfizer-BMS; speakers fees from Bayer, Biotronik, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Milestone Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer-BMS alliance, Centrix India, CTI Germany, ESC, Medscape and Springer Healtcare Ltd; unpaid participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board (member, DSMB Prestige-AF). W.D. declares research support to the institution from Vifor and Boerhinger; consulting fees paid to him from Aimediq, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Vifor Pharma, Cardiomatics and Icon Clinical research; travel support from Pharmacosmos; participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board (Boehringer, IQVIA); leadership or fiduciary role (ESC, councilor of the ESC Board, unpaid), ESC Council on stroke (nucleus member, unpaid); and Society of Cachexia and wasting disorders board member, unpaid. S.P. declares leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group, unpaid (ESC board member, Deputy Editor EHJ, Chair Pan-London cardiogenic Shock Board). H.P. declares payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Abott, Biosense Webster, Biotronik and Medtronic. P.K. declares grants or contracts: EU AFFECT-AF (grant agreement 847770), and MAESTRIA (grant agreement 965286), British Heart Foundation (PG/17/30/32961; PG/20/22/35093; AA/18/2/34218), German Center for Cardiovascular Research supported by the German Ministry of Education and Research (DZHK, grant numbers DZHK FKZ 81 × 2800182, 81Z0710116, and 81Z0710110), German Research Foundation (Ki 509167694), and Leducq Foundation); grants or contracts (P.K. receives research support for basic, translational, and clinical research projects from EU, British Heart Foundation, Leducq Foundation, Medical Research Council (UK), and German Center for Cardiovascular Research, from several drug and device companies active in atrial fibrillation); patents planned, issued or pending (listed as inventor on two issued patents held by University of Hamburg (Atrial Fibrillation Therapy WO 2015140571, Markers for Atrial Fibrillation WO 2016012783); leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group (board member ESC, Speaker of the Board, AFNET); receipt of equipment, materials, drugs, medical writing, gifts or other services (receives research support for basic, translational, and clinical research projects from European Union, British Heart Foundation, Leducq Foundation, Medical Research Council (UK), and German Center for Cardiovascular Research, from several drug and device companies active in atrial fibrillation, and has received honoraria from several such companies in the past, but not in the last 3 years). A.R.L. declares consulting fees (ARL); speaker, advisory board or consultancy fees and/or research grants from Pfizer, Novartis, Servier, Astra Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GSK, Amgen, Takeda, Roche, Janssens-Cilag Ltd, Astellas Pharma, Clinigen Group, Eli Lily, Eisai Ltd, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Akcea Therapeutics, Myocardial Solutions and iOWNA Health and Heartfelt Technologies Ltd.; participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board (ESC STEEER-AF Trial; PROACT Trial DSMB); leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group (chair of ESC Council on Cardio-Oncology); stock or stock options from Myocardial Solutions, Heartfelt Technologies and iOWNA. R.H. declares grants or contracts—institutional payments from Pfizer, Slovak Research and Development Agency; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Boehringer Ingelheim, Organon and Pfizer; support for attending meetings and/or travel (ESC, Pfizer); leadership or fiduciary role in other board (Slovak Heart Rhythm Association, President, unpaid). P.R. declares grants or contracts from the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, Payment to Institute for various research projects; Biosense Webster, payment to institute for the MANTRA-VT Trial; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events payments made to him (Biosense Webster; Stereotaxis); participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board (ESC STEEER-AF trial, no payment); leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group (ESC Nominating Committee member, UEMS Cardiology Section Treasurer); stock or stock options (Orion Pharma). The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Christopher Granger and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Michael Basson, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Tipping Point Sensitivity Analyses.

Graphs show the tipping point at which results will favor the control arm if participants with missing data at follow-up are imputed as being non-adherent to guidelines in the intervention arm and adherent in the control arm. Panel A for the stroke prevention co-primary outcome demonstrates that the tipping point only occurs after 95% of the missing data is imputed as non-adherent, and all of the missing data in the control arm are imputed as adherent. Panel B for the rhythm control co-primary outcome demonstrates that even if all missing data is imputed as non-adherent in the intervention arm and adherent in the control arm, this will still not provide a result that statistically favors the control group.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

CONSORT cluster checklist, trial protocol and statistical analysis plan.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kotecha, D., Bunting, K.V., Mehta, S. et al. Education of healthcare professionals to improve guideline adherence in atrial fibrillation: the STEEER-AF cluster-randomized clinical trial. Nat Med 31, 2647–2654 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03751-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03751-2