Abstract

Adverse outcomes after elective cancer surgery are a main contributor to decreased survival, poorer oncological outcomes and increased healthcare costs. Identifying high-risk patients and selecting interventions according to individual risk profiles in the perioperative period in cancer surgery is a challenge. Using real-world data on 18,403 patients with colorectal cancer from Danish national registries and consecutive patients from a single center, we developed, validated and implemented an artificial-intelligence-based risk prediction model in clinical practice as a decision support tool for personalized perioperative treatment. Personalized treatment pathways were designed according to the predicted risk of 1-year mortality with the intensity of interventions increasing with the predicted risk. The developed model had an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.79 in the validation set. Results from the nonrandomized before/after cohort study showed an incidence proportion of the comprehensive complication index >20 of 19.1% in the personalized treatment group versus 28.0% in the standard-of-care group, adjusted odds ratio of 0.63 (95% confidence interval, 0.42–0.92; P = 0.02). The incidence of any medical complication was 23.7% in the personalized treatment group and 37.3% in the standard-of-care group; odds ratio of 0.53 (95% confidence interval, 0.36–0.76; P < 0.001). According to the short-term health economic modeling, personalized perioperative treatment was cost effective. The study demonstrates a fully scalable registry-based approach for using readily available data in an artificial-intelligence-based decision support pipeline in clinical practice. Our results indicate that this specific approach can be a cost-effective strategy to improve key surgical clinical outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Despite advancements in surgical techniques and perioperative care over the last decades, postoperative morbidity and mortality represent common therapeutic challenges in surgery globally1. Several studies have demonstrated that targeted interventions in the period around surgery reduce postoperative morbidity2,3,4. However, patient selection for these interventions is a common challenge in clinical practice due to resource constraints among healthcare personnel and the lack of reliable risk assessment tools to identify patients who would potentially benefit from the intervention. To further advance precision medicine, decision tools for individualized assessment of patient risks for adverse outcomes are wanted that could enable the provision of targeted treatments tailored to each patient’s unique phenotype and potentially lead to a more effective allocation of healthcare resources. In recent years, several prediction tools using artificial intelligence (AI) techniques have been developed5. These models, designed to process large amounts of data and analyze complex patterns, have the potential to provide a patient-centric and holistic assessment of patient risk. It also opens a range of challenges in healthcare data access, data privacy, regulatory issues regarding data sharing across registries, integration to pre-existing electronic health records (EHRs) and, most importantly, demonstration of clinical benefit. Finally, when developing AI solutions, scalability is essential to ensure that the solutions can be expanded and implemented effectively across clinical settings. Although numerous prediction models for perioperative and postoperative mortality exist, integration into real-world clinical workflows is needed to enable personalized perioperative treatment decisions at the point of care. A stepwise implementation of a model, validated on national registry data and tested in real-world clinical settings, will facilitate both clinical usability and scalability. In this study, therefore, we designed, developed, implemented and evaluated an AI-supported decision support tool alongside personalized perioperative treatment bundles, establishing a stepwise approach to implementing a personalized treatment strategy. In the first step, we used registry data to investigate the relationships between various risk factors associated with adverse postoperative outcomes and defined the clinically relevant predicted outcome of interest. In the second step, we developed and validated an AI-based prediction model. In the third step, we implemented personalized clinical care of patients scheduled for elective curative intended surgery for colorectal cancer (CRC), using the prediction model as a decision support tool for surgeons treating the patients. Finally, in the fourth step, we assessed clinical outcomes and modeled the cost-effectiveness of implementing the proposed personalized perioperative treatment.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study cohorts

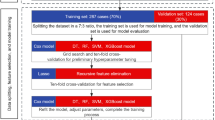

A National Registry-based cohort (NRC) comprised data from four national registry databases on 18,403 patients undergoing curative-intent surgery for CRC in an elective setting between 1 January 2014 and 1 April 2019. These data were used to identify the main challenges regarding clinical outcomes, model development and internal validation. The retrospective clinical cohort (RCC) consisted of 806 patients who underwent surgery between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2022 at a single center, and served as a data source for external validation of the model and as a comparative cohort for clinical outcome. After implementing the AI prediction model in clinical practice, the prospective clinical cohort (PCC) consisted of 194 patients undergoing surgery between 1 February 2023 and 31 December 2023 and represented patients treated with personalized perioperative treatment. Figure 1 represents the study flowchart. Figure 2 illustrates the study design.

The nationwide DCCG database, which includes information on all patients diagnosed with CRC between 1 January 2014 and 1 April 2019, served as the data source for the NRC, enriched with data from the DNPR, the DPR and the RLRR. The RCC included patients who underwent surgery for CRC at Zealand University Hospital during the period between 1 January 2020 and 31 January 2023. The PCC comprised patients treated at Zealand University Hospital during the period between 1 February 2023 and 31 December 2023. MDT, multidisciplinary team; cM1, clinical M1 category; pT1, pathologic T1 category; pCR, pathologic complete response; WW, watch and wait. Created using BioRender.com, https://BioRender.com/7dmw4xt.

a, The DCCG database was used for problem-based learning in which the relationships between several risk factors and mortality after surgery were explored, and the outcome of the prediction model was defined. b, Nationwide registry data were harmonized into the OMOP CDM and used for model development and internal validation. c, A retrospective clinical cohort of patients undergoing curative-intent surgery for CRC at the hospital hosting the prediction model was used to validate model performance externally. Simultaneously, clinical risk groups based on the predicted risk of 1-year mortality (A, ≤1%; B, >1% to ≤5%; C, >5% to ≤15%; D, >15%) were defined, followed by the development of risk-tailored intervention bundles targeting each risk group, with an increasing intensity of interventions for higher risk groups. d, A new local treatment paradigm was implemented on 1 February 2023, for patients scheduled for elective curative intended surgery for CRC, consisting of using the clinical prediction model as a decision support tool for clinicians to risk-stratify patients and refer patients to appropriate perioperative optimization bundles. Created using BioRender.com, https://BioRender.com/jttmuq3.

Problem-based learning

To investigate the potential need for multidimensional risk assessment, the association between 1-year survival and the Charlson comorbidity index (CC-index—a marker for the burden of comorbidity), the WHO performance status (WHO PS—a marker for general health status and activities of daily living), the Union for International Cancer Control stage (UICC stage—a marker for the anatomically extend of the oncological disease) and age were investigated in the NRC. Higher CC-index, WHO PS, UICC stage and age were all associated with shorter survival. All prognostic factors were further stratified by including postoperative complications, where postoperative complications were associated with shorter survival conditioned on either CC-index, WHO PS, UICC stage or age (Fig. 3a–d). Whereas each prognostic factor could stratify patients according to risk, the correlation between the risk groups was poor to moderate, with Spearman’s correlation coefficient between the factors ranging from −0.03 to 0.29 (Fig. 3e). The finding that several prognostic factors exist that are not highly correlated and can either be known or estimated preoperatively supports the idea that a preoperative risk assessment integrating several health domains may better capture the variability in postoperative mortality compared to single-dimensional risk assessment tools.

a–d, Kaplan–Meier curves for 1-year postoperative mortality for patients undergoing elective curative intended surgery, stratified by whether patients developed a postoperative complication graded as CD 2 or higher during the first 30 days following surgery different factors: age group (a), CC-index (b), WHO PS (c) and UICC stage (d). e, Correlation matrix between each factor and the development of postoperative complications graded CD 2 or higher and Spearman’s rho between each factor.

Development and validation of the 1-year mortality prediction model

During model development, 8,694 covariates were identified initially as potential covariates; through hybrid data-driven clinical supervised selection, 68 candidate covariates were included for model training, of which 58 were included in the final model. The covariates and regression coefficients are summarized in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Covariates with a coefficient of 0 do not influence model output and were removed from the final model. The predicted probability of 1-year mortality for a given patient can be estimated using the logistic function: \(\frac{1}{1+{{e}}^{-{x}}}\), where x is the sum of the pairwise products of the included covariates and regression coefficients plus the intercept. The performance of the model as a binary classifier is summarized in Fig. 4a. Discrimination metrics showed an area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) (AUROC) of 0.82 (95% confidence interval (CI), 0.81–0.84) for the model development set compared to an AUROC of 0.77 (95% CI, 0.74–0.80) for the internal validation set and 0.79 (95% CI, 0.71–0.87) for the external validation set (Fig. 4b). The sensitivity for selected threshold was 0.40 (95% CI, 0.36–0.44), 0.32 (0.27–0.38) and 0.50 (0.34–0.65) for the model development, internal validation and external validation set, respectively. Model calibration, evaluated as the number of observed versus expected events, showed near-ideal point estimates for the development sets and internal validation sets. Figure 4c shows the calibration curves for the model development sets and internal validation sets, illustrating the observed (rolling averaged) versus the predicted (rolling averaged) risk using the locally estimated scatterplot smoothing. Both curves suggested that the model is well calibrated at lower predicted risks. But at higher observed risk, the model tends to overpredict, that is, the predicted probability was higher than the observed event proportion. Based on the development set, the model started to overpredict after the predicted risk exceeded 40% whereas, based on the internal validation set, the model began overpredicting after the predicted risk exceeded 10%. Due to insufficient outcome events, the calibration curve for the external validation set was not investigated. For study use, model calibration was satisfactory, as the prediction model is used only to support clinicians’ stratification of patients into perioperative optimization bundles, where overtreatment is considered safe. A slight overprediction for patients where the predicted risk was between 10% and 15% could cause some patients to be suggested to a higher risk group, that is, more intensive perioperative optimization, which was clinically acceptable, whereas overprediction for predicted probability exceeding 15% would not affect the suggested risk group. The overall model fit was investigated using the Brier score, which was 0.043 (95% CI, 0.040–0.046), 0.046 (95% CI, 0.041–0.0513) and 0.044 (95% CI, 0.034–0.056) for the model development set, internal validation set and external validation set, respectively.

a, Metrics of fit, discrimination and calibration across the development, internal validation and external validation sets together with 95% CIs. For negative predictive value (NPV), positive prediction value (PPV), sensitivity and specificity, a threshold of 0.15 was used to classify predictions as an event. b, ROC curves for the development, internal validation and external validation sets. Data are presented as the estimated curve with error bands representing 95% CI. c, Calibration curves for the development and internal validation sets. Data are presented as the estimated curve with error bands representing 95% CI. d, Barcharts of the incidence proportion and total counts of postoperative events across the development (n = 13,803), internal validation (n = 4,600) and external validation (n = 806) sets, stratified by risk group A (predicted risk of 1-year mortality ≤1%), B (predicted risk of 1-year mortality >1 to ≤5%), C (predicted risk of 1-year mortality >5 to ≤15%) and D (predicted risk of 1-year mortality >15%). The postoperative events include 1-year mortality, medical complications graded as CD 2 or above within 30 days following surgery, and surgical complications graded as CD 3a or above within 30 days following surgery. Data are presented as the proportion of events per risk group, with error bars representing 95% CI.

Clinical relevance of risk groups

Four clinical risk groups (A, B, C and D) were defined according to predicted risk of 1-year mortality of ≤1%, >1% to ≤5%, >5% to ≤15% or >15%, respectively. Figure 4d shows the incidence proportion of medical complications within 30 days graded as Clavien-Dindo (CD) ≥2, surgical complications within 30 days graded as CD ≥3a and mortality within 1 year following surgery for the model development, internal validation and external validation sets, stratified by the predicted risk group. The figure shows a monotonic increase in the observed incidence proportion of all outcomes with higher risk groups in all evaluation sets except the surgical complications in the external validation set, where fewer complications were observed in group B than in group A. For all evaluation sets and risk groups, the observed event rate of 1-year mortality was within the boundaries set for the risk groups. However, 95% CIs frequently overlapped between groups, and the event rate of medical complications was higher in the external validation set, indicating a systematically higher yield of events in chart reviews compared with registry-based data registration practice, which is consistent with the validation of the register6.

Clinical outcomes before and after implementation of personalized perioperative treatment

For the RCC and PCC, the mean predicted risk for the 1-year mortality was 3.24% and 3.68% (W-statistic (W) = 77,836; P = 0.924), whereas the mean predicted risk stratified by risk group was 0.66% versus 0.68% for group A (W = 1,986; P = 0.316), 2.41% versus 2.56% for group B (W = 19,924; P = 0.294), 8.17% versus 8.78% for group C (W = 6,130; P = 0.652) and 22.5% versus 18.6% for group D (W = 356; P = 0.196). Although no statistically significant association between the clinical cohorts and the predicted risk was found, the clinical cohorts were statistically associated with the distribution risk groups, with 131 (16.3%), 373 (46.3%), 207 (25.7%) and 95 (11.8%) patients assigned to risk groups A, B, C and D in the RCC, whereas the distribution was 27 (13.9%), 100 (51.5%), 57 (29.4%) and 10 (5.2%) in the PCC (χ2 = 8.818; d.f. = 3; P = 0.032). Although the overall agreement between the risk group suggested by the model and the risk group chosen by the clinicians was high (κ = 0.926), nine (4.6%) cases were adjusted from suggestion made by the decision support tool: one patient predicted as group A was treated as group B, four patients predicted as group B were treated as group C and one was treated as group A, two patients predicted as group C were treated as group B, and one patient predicted as group D was treated as group C. One-year mortality was 5.2% across all study cohorts, except for the PCC, where follow-up was still ongoing and therefore not reported. Patient demographics are summarized in Table 1.

Comprehensive complication index

The incidence proportion of comprehensive complication index (CCI) > 20 in the PCC was 19.1% compared to 28% in the RCC; the incidence proportions are shown in Fig. 5a (left). Univariate logistic regression showed that the personalized perioperative treatment was associated with significantly lower odds of CCI > 20 than standard of care (odds ratio (OR) = 0.60; 95% CI, 0.40–0.88; P = 0.011). Moreover, risk groups C and D had significantly higher odds for CCI > 20 compared to risk group A (OR = 1.76; 95% CI, 1.12–2.81; P = 0.015 and OR = 2.53; 95% CI, 1.47–4.38; P < 0.001, respectively). After adjusting for risk groups in a multivariable logistic regression, a similar association for the personalized perioperative treatment compared to the standard of care was found (OR = 0.63; 95% CI, 0.42–0.92; P = 0.02). Results are summarized in Fig. 5a (right).

a–d, Incidence proportion (left) and results of univariate and multivariate regression analyses using logistic regression or negative binomial regression as appropriate (right) of CCI > 20 (a), incidence proportion of medical complications (b), IR of number of postoperative complications (c) and IR of the number of postoperative readmissions (d) for the PPC (after implementation of personalized perioperative treatment) and the RCC (control), stratified by risk groups A, B, C and D and overall. The regression models included either the treatment, the risk group or both as independent variables versus the outcome. The model coefficients are expressed as ORs for logistic regression or as IRRs for negative binomial regression, along with 95% CIs and associated two-sided P values based on Wald’s test, without adjustment for multiple comparisons. PPT, personalized perioperative treatment.

Postoperative medical complications

The incidence proportion of medical complications was 23.7% in the PCC versus 37.3% in the RCC; Fig. 5b (left) shows the incidence proportion of medical complications. In univariate logistic regressions, significantly higher odds for medical complications were found for standard care compared to personalized perioperative treatment (OR = 0.52; 95% CI, 0.36–0.74; P < 0.001). Also, risk groups C and D had higher odds for medical complications compared to risk group A (OR = 2.36; 95% CI, 1.53–3.70; P < 0.001 and OR = 3.34; 95% CI, 1.98–5.71; P < 0.001, respectively). After adjusting for risk groups, a similar association between personalized perioperative treatment and standard of care in multivariable logistic regression was found (OR = 0.53; 95% CI, 0.36–0.76; P < 0.001). Results are summarized in Fig. 5b (right).

Counts of postoperative complications

The incidence rate (IR) of postoperative complications was 0.48 of 90 days in the PCC versus 0.76 of 90 days in the RCC; Fig. 5c (left) shows the average number of postoperative complications in the first 90 days. In univariate negative binomial regression model, personalized perioperative treatment was associated with a lower IR compared to the control (IR ratio (IRR) = 0.63; 95% CI, 0.48–0.83; P = 0.001). Both risk groups C and D were associated with higher IR compared to risk group A (IRR = 1.97; 95% CI, 1.42–2.75; P < 0.001 and IRR = 2.63; 95% CI, 1.80–3.88; P < 0.001, respectively). When adjusting for risk groups in a multivariable negative binomial regression, similar associations were found between personalized perioperative treatment and standard of care (IRR = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.50–0.87; P = 0.003), and the results are summarized in Fig. 5c (right).

Counts of readmissions

On average, patients in the PCC had 0.2 readmissions during the first 90 days after surgery, whereas patients in the RCC had 0.31 readmissions in the same period; Fig. 5d (left) shows the average number of readmissions in the first 90 days following surgery. The personalized perioperative treatment was statistically significantly associated with the number of readmissions in univariate negative binomial regression models (IRR = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.43–0.95; P = 0.028). Controlling for the risk group in a multivariable negative binomial regression produced similar IRR and P value for the personalized perioperative treatment versus the standard of care (IRR = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.44–0.98; P = 0.041). The results are summarized in Fig. 5d (right).

Cost-effectiveness analysis

A cost-effectiveness analysis of the AI-targeted treatment compared to standard of care was performed using a hybrid decision tree and Markov state transition model with a 1-year time horizon. Cost per patient was estimated to US $28,006.94 in the standard-of-care arm, whereas the cost in the personalized perioperative treatment arm was estimated to US $25,159.36, leading to cost savings of US $2,847.59 (2,810.32 to 2,884.00) during the first year following surgery. The incremental gain in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) was estimated to 0.020 per patient (0.020–0.020). The sensitivity analysis showed that the personalized perioperative treatment dominated standard care in the short term, with a reduction in costs and positive health gains in 96.56% of the simulations (Supplementary Fig. 1a), demonstrating that the personalized perioperative treatment, given the applied model assumptions, was cost effective (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

Discussion

In this study, we roadmapped the steps needed from clinical problem framing to the clinical implementation of an AI-based decision support tool, pragmatically using AI technologies that harness real-world data from nationwide healthcare registries.

We observed fewer postoperative adverse events after deploying an AI-based decision support tool for individual risk assessment and personalized perioperative treatment of patients scheduled for CRC surgery.

So far, AI-based decision tools are typically limited to research settings. A common challenge in previous attempts to introduce AI technologies into the healthcare system has been their lack of clinical usability and excessive complexity7. To overcome these challenges, we established a multidisciplinary collaboration between clinicians and data scientists who identified the clinical problem, defined desired outcomes and developed a solution that was scalable within the current infrastructure. The prediction model developed and validated in this study successfully achieved the desired outcome, demonstrating satisfactory performance in meeting the proposed objective. One of the key contributions of our study is therefore bridging the gap between AI-based prediction models and their real-world clinical implementation. The translation of AI predictions into actionable treatment modifications represents a shift from traditional predictive analytics to a truly interventional AI application in surgery.

Prediction models employing more advanced methodologies have been developed previously8. However, the clinical information technology infrastructure might be a limiting factor for practical implementation as, to be clinically feasible, models with more advanced, or high amounts of, input variables will require automatic data retrieval for populating decision support tools9. Near endless strategies for implementing clinical prediction models can be imagined. However, decision-making in surgery presents a clinical use case where both overtreatment and undertreatment can disadvantage patients. Several factors, including the complexity of cases, time constraints and uncertainty, may bias decisions, as reviewed previously5.

In the current study, several strategic decisions were made to develop an implementable system for personalizing perioperative care. The prediction model was developed upon a well-characterized national quality assurance database, which has been validated previously6. This database contains a substantial amount of prospectively collected patient cases and is used extensively for scientific projects as well as for monitoring the quality of clinical care of patients with CRC in Denmark. The familiarity with a data source in which all surgical departments in Denmark are involved and which has an empirical claim of data validity, helped build trust in the data foundation for the clinicians using the tool. Second, a standard data format and model framework designed to facilitate best practices were chosen to ensure methodological validity10. Third, we involved colorectal surgeons in the development process to ensure the model addressed a genuine clinical need, fostering trust in the tool and confirming that the use case reflected a real-world clinical problem from the perspective of the clinical staff. Fourth, validating the model on local data collected from EHRs at the center where it was intended to be used helped highlight the soundness of using the tool to stratify patients for perioperative optimization. Finally, using treatments with empirically proven effects, such as preoperative high-intensive interval training with a favorable risk profile2, and targeting the underutilized perioperative treatment window11, were deemed to be a straightforward target, with a safe risk profile and a high probability of clinical benefit, which helped get the support of clinicians, local leadership and patients. Development of future clinical data-driven products might benefit from the study’s experience with early multidisciplinary collaboration between clinical, technical and scientific staff to frame a clinical problem into a data problem and identify appropriate data and methods for development.

This study addresses an important clinical problem. Postoperative mortality ranks as the third leading cause of death worldwide1. Postoperative complications not only greatly impact postoperative mortality but also considerably augment healthcare costs, further straining an already pressured healthcare system and making this a global concern12. The risk of postoperative complications is multifactorial, with frailty phenotype and comorbidities being leading contributors13. Relationships between these factors are nonlinear and multifactorial, and our study highlights challenges related to patient risk assessment. AI-based models enable complex relationships between variables in large datasets to be uncovered, making them ideal for risk assessments in healthcare settings. However, for practical problems, using methods with too much flexibility can result in overfitted models, whereas too little flexibility can result in loss of potential performance; choosing the appropriate model architecture is thus one of the main challenges for machine learning engineers. In the current study, the main objective was the clinical implementation of the model. During development, when a model performed satisfactorily, the simplest model was chosen. Using the simplest model also made deployment easy, as the decision support tool can be implemented with a simple app taking the model parameters as input, imputing missing variables using the same rules as for model training and calculating the risk based on the logistic function. By incorporating a range of patient data domains (for example, demographics, frailty measures, comorbidities, health behavior measures, biomarkers), the model was able to learn from a somewhat broad data representation of patients to generate personalized predictions about postoperative risk. This can help tailor preoperative optimization strategies for patients, as being guided by only single risk measures can lead to contradictory information. Interventions aimed at preventing or mitigating postoperative complications have been shown to be particularly beneficial for subgroups of patients at higher risk of adverse outcomes, which is consistent with the present finding where the absolute difference in incidence proportions or IRs were greater in the subgroups with a higher predicted risk of 1-year mortality14. Further, the decrease in postoperative complications in our study clearly highlights these findings and is consistent with a recent randomized clinical trial in a similar setting2.

Given the high cost and logistical challenges of conducting randomized controlled trials in clinical settings, more pragmatic studies can effectively inform initial evaluations and guide the design of future large-scale trials15. Furthermore, we modeled the cost-effectiveness of the targeted treatment against the standard of care and estimated the incremental costs and health effects, measured in terms of quality of life, for the first year after surgery. We demonstrated a notable cost savings potential from deploying the AI prediction model, which was followed by individualized treatment trajectories. Despite the limitations associated with simulated data, our findings demonstrate that AI-based decision support tools for individual risk assessment could offer opportunities for targeted interventions that aim at improving health outcomes among high risks and save costs, allowing for more cost-effective resource allocation. Furthermore, the current health economic model investigated only the short-term effects of AI-supported personalized perioperative treatment, warranting further research into the long-term consequences of the treatment paradigm.

The study’s limitations include the fact that it cannot establish any causal relationship between the implementation of personalized perioperative treatment and improved postoperative outcomes. The assignment of interventions to risk groups was guided by existing clinical guidelines, expert consensus and retrospective observational data. Although our approach enables stratified perioperative optimization, refining the interventions in treatment bundles and improving treatment bundle allocation could be an objective of future studies, where the risk of a given outcome can be modeled using patients’ characteristics under different treatment strategies using a causal prediction framework16,17. Integrating such findings into the personalized perioperative treatment paradigm may enhance patient outcomes further by identifying individualized treatment effects, further supporting clinical decision-making. Future studies may benefit from using more data-efficient methods to estimate model performance than split-sample validation, such as crossvalidation or bootstrapping, more sophisticated methods for imputation, including multiple imputation, and estimating confidence intervals analytically rather than using bootstrapping18,19. Moreover, the relatively small sample size of the prospective cohort, although sufficient for demonstrating feasibility and implementation insights, limits the ability to draw definitive conclusions on clinical benefit. Further, the study did not investigate whether standardized treatment bundles or introducing a decision support tool to identify patients with a high risk of poor postoperative outcomes could drive the observed decrease in complication rates. To address this knowledge gap, a multicenter randomized controlled trial (NCT06645015) is being planned in Denmark to evaluate the effect of the decision support tool at centers with standardized perioperative optimization bundles. Despite these limitations, as well as the inherent problems with comparing patients from different time periods, the relatively low number of patients and the single center origin, our study still supports the potential benefit of using AI to identify patients who might benefit from targeted interventions, showed a notable reduction in severe postoperative outcomes and serves as a proof-of-concept of the paradigm, offering pioneering insights into the practical application of AI technologies.

In conclusion, we believe that our study addresses the current challenges associated with the deployment of AI in the field of surgery. We demonstrate the clinical utility of AI technologies and offer an adaptable framework for further scalability to other healthcare fields. Moreover, we believe that findings from this study may accelerate the ongoing paradigm shift in perioperative care towards personalized medicine.

Methods

Ethical statement

The study complies with all relevant ethical and regulatory standards, including the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Medical Device Regulation (MDR, EU 2017/745). The model development was based on registry data, did not require ethical approval or informed consent, and was registered in Region Zealand’s research inventory (REG-102–2020). The collection of EHR data for model validation, as well as data collection for the prospective clinical cohort, and the prospective implementation of the algorithm was approved as a clinical quality improvement initiative by Zealand University Hospital’s institutional leadership (Approval ID: 10736955 and 11329111). Informed consent was formally waived, as permitted under Danish law for quality improvement projects. The AI decision support tool was developed and implemented in accordance with MDR Article 5(5), which governs inhouse medical device use in healthcare institutions, and fulfilled requirements for clinical performance, risk management and institutional oversight.

Cohorts

This was a nonrandomized comparative cohort study consisting of three cohorts: an NRC, an RCC and a PCC.

The NRC consisted of data from the Danish Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG), enriched with data from The Danish National Patient Register (DNPR), The Danish Prescription Registry (DPR) and the Register of Laboratory Results for Research (RLRR). These data were used for model development and internal validation. Data on all patients undergoing a curative intended surgery in an elective setting for adenocarcinoma of the colon and/or rectum in the period 1 January 2014 to 1 April 2019, was collected from the DCCG database20. DCCG is a nationwide clinical quality register, which covers more than 99% of patients operated for CRC in Denmark since 2001. The dataset was enriched with data on a patient level with nationwide prescription data since 1995 from DPR21, with nationwide data on biochemical and immunological biomarkers from RLRR since 2013–201522, and with trajectory data from public Danish hospitals from DNPR since 197723. The data sources were harmonized into the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) common data model (CDM)24. A multidisciplinary team (MDT) of data scientists and medical doctors was responsible for transforming the registry data to the OMOP format, where source data were mapped to representative concepts in the OHDSI Standardized Vocabularies25 and tables, following a process of one medical doctor mapping the concept, another reviewing the mapping and suggesting updates to the initial mapper. Cases where the initial mapper and the reviewer doubted the solution or did not agree were flagged for plenary team discussion, where a decision was made. Clinicians and data scientists worked together to define an extract, transform and load logic to create a database, where an automated tool developed by the OHDSI community was used to identify potential data quality errors26.

The RCC was used for external validation of the model and as a comparative cohort against the PCC. Data were retrieved locally from EHR at the Department of Surgery at Zealand University Hospital in Denmark for all patients undergoing elective, curative-intent surgery for CRC from 1 January 2020 to 31 January 2023. To ensure accuracy and reliability, all collected data underwent monitoring, querying and validation by the senior investigator. Assessors who reviewed medical records received a structured introduction to the database before data entry. The primary investigator validated the first 20 records for each assessor. Any inconsistencies in data capture were discussed with the assessors and corrected accordingly. Thereafter one out of every ten records was checked randomly for ongoing validation. Assessors had regular opportunities to discuss cases with the primary investigators, and consensus was reached during panel discussions when needed. The PCC cohort was represented by all patients referred to the MDT meeting at Zealand University Hospital, Denmark, with suspected CRC who were deemed eligible for curative-intent surgery during the period from 1 February 2023 through 31 December. Patients scheduled for emergency surgery, defined as surgery within 72 h of the initial outpatient clinic visit and/or a preceding emergency department visit, as well as those patients requiring additional evaluation or procedures before elective CRC surgery were excluded. An AI-based risk prediction model for 1-year mortality, followed by personalized treatment pathways for perioperative optimization according to the predicted mortality risk, was implemented as standard treatment at Zealand University Hospital for all eligible patients on 1 February 2023. Thereby, the PCC cohort was used as an intervention cohort for a clinical trial. A prospectively maintained database, managed using an EHR form in REDCap27, was established to serve as the data source for the PCC cohort. Accuracy, reliability and validity were ensured in the same manner as for the RCC database.

Reporting on sex followed The Sex and Gender Equity in Research—SAGER guidelines28. In all three study cohorts, an adequate representation of both male and female patients was expected, as all patients diagnosed with CRC and eligible for elective, curative-intent surgery were included, representing the CRC population. No exclusions were made based on sex. Sex was recorded as biological sex based on registry or EHR data. Information on gender was not available and was not collected.

Problem-based learning

A local panel consisting of colorectal surgeons, epidemiologists and data scientists was established to investigate drivers of poor postoperative trajectories and potential risk-reducing initiatives. Data from the DCCG on the NRC was used as the data foundation for the study due to its availability, validity and broad inclusion of valuable data for patients operated on for CRC. The panel agreed that identifying high-risk patients and introducing targeted interventions would be a high probability of success strategy. We used 1-year mortality as a surrogate for poor postoperative outcomes due to the high reliability of vital status available through the Danish Civil Registration System29 and the previous studies showing substantial differences in 1-year mortality after elective CRC surgery according to generic frailty indicators and correlation with postoperative morbidity30,31. The association between four prognostic factors, representing different aspects of health domains, age at time of surgery (<50 years, 50–59 years, 60–69 years, 70–79 years, ≥80 years), CC-Index groups (0, 1–2, 3–4, ≥5), WHO PS and UICC stage, and overall survival time was investigated using unweighted Kaplan–Meier curves and inspected visually. For each prognostic factor level, data were stratified further by whether at least one postoperative complication graded CD 2 or higher32 occurred. The correlations between prognostic factors were investigated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient for all complete pairs of variables.

Framework of the 1-year mortality prediction model

The development of a prediction model to support decision-making in perioperative planning has been discussed and supported by representatives from the Danish Colorectal Cancer Patient Association, as part of the Enhanced Perioperative Oncology Consortium. The NRC cohort was used to develop the prediction model, using the standardized framework for developing clinical prediction models, PatientLevelPrediction33, which is interoperable with the OMOP format. The study used death within 1 year following surgery, defined as death from any cause between day 0 and day 365 from the date of surgery, as the outcome variable. In addition, risk groups were created based on a clinical request to guide perioperative optimization pathways. Patients were grouped by their predicted risk of 1-year mortality following surgery: ≤1%, >1 to ≤5%, >5 to ≤15%, or >15%, styled as group A, B, C and D. For each group the proportion of patients dying within 1 year after surgery was calculated for the model development, internal validation and external validation sets by risk group. Further, surgical complications graded as CD ≥3a and medical complications graded as CD ≥2 within 30 days were also reported for each risk group to support the clinical value of the risk groups.

Selecting covariates for the 1-year mortality prediction model

The selection of candidate covariates was developed iteratively. Initially, a data-driven model was trained using age, sex and all conditions occurrences, drug exposures, procedure occurrences, observations and measurement values, with any event occurring within 30 days, 365 days, 1,825 days or any time before the index date. Variables were ranked based on their standardized mean difference and presented for clinicians, who identified thematic variables as a base to construct new input variables or keep them as is for the training of the clinical model (for example, combining codes that represent ischemic heart disease or diabetes mellitus, or keeping a measurement as it is). For laboratory measures, the candidate covariates were chosen based on routinely available blood tests performed preoperatively before elective cancer surgery at the center where the model would be implemented. The final candidate covariates were all designed to be feasible for clinicians to retrieve during the preoperative planning, either through the EHR system or during the preoperative outpatient clinic visit. The list of candidate covariates was reviewed by clinical personnel, who could request covariates not included through the initial process.

Sample size for the 1-year mortality prediction model

A post hoc calculation of the minimum sample size of patients needed to develop a clinical prediction model was performed using the method described by Riley et al.34 The calculation assumed 68 candidate covariates, that the model would explain 10% of the variability and the prevalence of the outcome would be 5.2%. The minimum number of patients needed to develop the model was 6,941 to develop a clinical prediction model with an acceptable difference in apparent and adjusted R-squared and margin of error in the estimation of the intercept of 0.05.

Missing data

Missing data were handled in three ways: for body mass index, clinical T category, clinical M category, alcohol consumption and smoking status, a specific code for missing values was used. For diagnosis, drug exposures and procedures, an absence of a positive code was considered as negative, having no option for missing. For continuous variables, missing values were imputed by the median value of the register data.

Development and validation of the 1-year mortality prediction model

A standardized framework for developing prediction models was used for model training and internal validation33. The registry data were stratified by outcome and split into a model development set containing 75% of the patients used for model development and an internal validation set containing 25% of the patients. The RCC was used for external validation, representing the population where the prediction model was to be implemented. The model was validated externally using the predicted and observed 1-year mortality and further investigated for clinical usefulness by investigating the incidence proportion of 1-year mortality, medical complications and surgical complications in predefined risk groups incrementally increasing the predicted risk of 1-year mortality. The RCC timeperiod did not overlap the NRC (development and internal validation), with the RCC (external validation) being more recent. Model development was done using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) logistic regression as a statistical learner with fivefold crossvalidation in the model development set, implemented with cyclic coordinate descent algorithm to optimize the likelihood function35. The method allows for estimating an optimal hyperparameter based on the crossvalidation. For all covariates, the model used simple linear relationships. Feature selection was based on the property of the LASSO regression to shrink covariate coefficients to 0, thereby having no effect on the prediction36. Model performance was evaluated in the model development, internal validation and external validation sets. Calibration was evaluated using calibration-in-the-large and moderate calibration from a previously published framework37. Calibration-in-the-large was assessed using the ratio of observed events versus the expected number of predicted events, whereas moderate calibration was assessed visually using flexible calibration curves created with locally estimated scatterplot smoothing. Calibration curves were investigated only for evaluation sets containing at least 200 events and nonevents37. Discrimination was evaluated using the AUROC and sensitivity with a threshold value of 0.15. CIs for the calibration-in-the-large and calibration intercept were estimated based on 10,000 bootstrapped resamples. Reporting was done in accordance with the TRIPOD+AI guideline38 (checklist available in supplementary information).

Clinical implementation of the 1-year prediction model

To accommodate the need for data storage, computational power and high-level security, the IT infrastructure was developed in a secure private cloud and hosted by the Danish National Life Science Supercomputing Center39. Consultant surgeons received secure cloud environment access through multifactor authentication. Data were extracted from patient EHR manually, and model output data were extracted and registered in the EHR.

The AI-based clinical decision support tool was developed and deployed as an inhouse software solution within Zealand University Hospital, adhering to the Medical Device Regulation (MDR, EU 2017/745, Article 5(5))40, which governs the development and use of medical software within healthcare institutions. Compliance with MDR 5(5) ensures that the system meets state-of-the-art validation, risk management and clinical governance requirements, supporting its safe and effective implementation in clinical practice.

All patients referred to the MDT meeting at Zealand University Hospital, Denmark, with suspected CRC during the period from 1 February 2023 through 31 December 2023, were risk stratified by a consultant surgeon before the MDT meeting. During the first outpatient visit, input data were modified, if necessary, according to eventual discrepancies in information used for initial risk assessment, and updated output data were imported into the patient’s EHR.

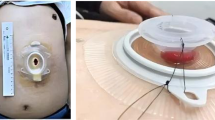

Individual treatment pathways according to risk profile

The individual treatment pathways were tailored according to the risk group of the patient. The risk group was allocated according to the prediction model risk profile A, B, C and D and used as a decision-making tool, enabling the possibility of adjusting the risk group based on clinical judgment when deemed necessary by colorectal surgeons. Individual treatment pathways were predefined based on the assigned risk group and consisted of interventions designed based on existing evidence within perioperative optimization in addition to standard postoperative protocol based on enhanced recovery after surgery protocols41. The individual interventions in a bundle class A, B, C or D were not picked by the clinicians at their discretion but were administered as a standardized bundle, including all the elements for the particular bundle. The intensity and frequency of interventions increased with the predicted 1-year mortality risk group. Due to the study’s complexity and the several interventions, a detailed description of interventions following CERT42 and TIDieR43 guidelines is provided in the Supplementary Information. Briefly, the main interventions in the preoperative period included interventions directed towards correcting iron deficiency anemia (intravenous iron supplementation), nutritional deficit (consultation by a dietician with use of specific protein supplementations), functional deficit (nonsupervised and supervised training according to risk profile), geriatric assessment and respiratory physiotherapy according to risk profile. The intraoperative interventions constituted goal-directed therapy protocols. For hemodynamic monitoring, lithium dilution cardiac output was utilized. Stroke volume and stroke volume variation were used to assess fluid responsiveness. Perfusion index and central venous oxygen saturation were used for decision support. Fluid therapy was administered according to the Danish Society of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine44. In the postoperative period, the main interventions constituted standardized discharge criteria from the postoperative care unit (POCU) after consultation with both the consultant anesthesiologist and the consultant surgeon according to risk profile. Patients in group D were admitted to the POCU for the first 24 h after surgery. All patients in group D were consulted by the operating surgeon and anesthesiologist within the first 2 h after surgery. Goal-directed therapy was continued during their stay at the POCU. Patients in group D were assisted individually by a nurse who was educated in the enhanced recovery after surgery protocol. Opioid-sparing pain management was applied for all patients; a transversus abdominis plane block or transmuscular quadratus lumborum block was administered if necessary. According to the risk profile, the patients were offered postoperative physiotherapy, delirium screening and nutritional intervention. All patients were discharged according to standardized criteria, including assessment for sufficient bowel function, mobility and pain control.

Before/after implementation of personalized perioperative treatment

To assess the comparability of the RCC and the PCC, baseline characteristics were compared across key demographic and clinical variables. To further minimize selection bias, the same inclusion criteria and data sources were applied to both cohorts. A comparison of postoperative events between the PCC and RCC was used to investigate the association between the implementation of the personalized perioperative treatment supported by a clinical prediction model as a decision support tool. In the RCC cohort, perioperative optimization strategies were applied based on clinical judgment and MDT discussions with specific optimization efforts as reported previously2,45,46,47. The main elements of the optimization bundle were consistent between the two cohorts. With the implementation of the prediction model, a standardized decision support tool was introduced, ensuring a structured risk stratification process guiding intervention intensity according to predefined risk categories. The main outcome was the incidence proportion of severely complicated postoperative courses, defined as CCI > 20 within 90 days after CRC surgery. This specific cutoff value of CCI > 20 as a measure of clinical relevance for severely complicated postoperative courses was determined based on findings from a recent randomized clinical trial2. Further outcomes included the number of readmissions, defined as the count of all-cause unplanned admissions to a hospital lasting more than 24 h within 90 days after index surgery, the number of postoperative complications was defined as the count of adverse deviation from the expected postoperative course in the first 90 days postoperatively, and any medical complications, defined as any adverse deviation from the postoperative course associated, but not linked directly to the surgical procedure during the first 90 days postoperatively.

Statistical analysis of the clinical outcomes in the before/after comparison

Continuous variables are presented as medians with the first and third quartiles. Categorical variables are presented as counts and fraction percentages. Hypothesis testing was performed using regression models and chi-squared and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. The agreement between the risk group suggested by the decision support tool and the risk group chosen by the clinicians in the PCC was reported using an unweighted Cohen’s kappa coefficient. Relationships between outcomes and variables were modeled using either a univariate model containing only treatment with the treatment paradigm as a binary variable, or a multivariable to account for the differences in risk group distribution, where both the treatment paradigm and the risk group were included as independent variables. The binary outcomes (CCI > 20 and any medical complications) were modeled using logistic regression, whereas count data (number of readmissions and number of complications) were modeled using a negative binomial regression. Two-tailed P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

Hybrid decision tree and Markov model structure

The hybrid decision tree Markov (HDTM) model was developed to evaluate the short-term cost-effectiveness of personalized perioperative treatment compared to standard care with a time horizon of 1 year after surgery. The HDTM model simulated the expected costs and QALYs for a hypothetical cohort undergoing either the standard of care or the personalized perioperative treatment. Detailed information on the model cohort, transition probabilities, costs and utility scores for model states are available in Supplementary Information. The simulation was based on a hypothetical cohort of patients with a base case risk group distribution as the RCC. The HDTM assumed patients received postoperative bundle care according to risk group under the personalized perioperative treatment, while all patients’ standard of care was assumed in the standard-of-care arm to receive the same treatment. For the decision tree component of the model, the proportion of patients developing a complicated postoperative trajectory versus a noncomplicated postoperative trajectory was determined based on parameter estimates of the risk group and treatment effect. A complicated postoperative trajectory was defined as any patient with a complication graded 2 or above on the CD scale, as this corresponds to a CCI score of at least 20.9. For the Markov simulation, cycle length was set to 1 day (and repeated 365 times) with the health states (decision nodes) representing different levels of contact with the healthcare sector: ‘healthy (no contact),’ ‘inpatient visit,’ ‘outpatient visit,’ ‘general practitioner visit’ or ‘dead.’ The initial state was set to ‘inpatient’ for all patients on day 0. Transition probabilities were based on data from RCC and PCC with a relative increase in complicated trajectories of 5% in risk group A, 40% decrease in risk group B, 16% decrease in risk group C and 51% decrease in risk group D for the personalized perioperative treatment. Thus, the only difference between the personalized perioperative treatment and standard of care, aside from intervention costs, was the difference in distributions between uncomplicated versus complicated trajectories. A probabilistic sensitivity analysis was constructed to address the total parameter uncertainty, where the output was per risk strata complication combination for both the standard of care and the intervention strategy. Utilities were transformed into QALYs by adding the days alive during the study period. Based on the estimated costs and QALYs, the personalized perioperative treatment was evaluated against the standard of care, and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was calculated.

Costs and health effects

An extended healthcare sector perspective was applied, including costs of inhospital care, outpatient care, general practitioner visits and prescription medicine. Discounting was not applied. Detailed information on costs and health effects is described in the Supplementary Information, together with Supplementary Tables 3–5. In summary, gross cost estimates for the model trajectories were based on the healthcare consumption of the NRC. All unit costs were valued using year 2023 prices. Danish Diagnose-Related Group tariffs were applied as unit costs for hospital care obtained from DNPR, whereas the unit cost of a general practitioner visit was set to the base tariff per visit based on the services and related tariffs between the Organization of General Practitioners and the Regional Board of Salaries and Fees for General practice. Costs of prescription medicine were estimated from the DPR using drug prices48. Costs associated with implementing the personalized perioperative treatment included costs associated with hosting the decision support tool, salary for system administrators, hourly wages for hospital staff and utensils used. Health effects were measured using QALYs and were based on utility scores derived from EQ-5D-5L questionnaires for 139 patients from the PCC. Relative decreases in utility were assumed for the inpatient state and all complicated trajectories. The health effects were assumed to be identical across the two treatment arms but with a different distribution of uncomplicated and complicated trajectories.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Due to Danish legislation protecting sensitive personal information, the source data cannot be shared. Currently, the Danish Data Protection Agency accepts no deidentification measures as fully anonymizing the data. As such, patient-level data cannot be shared. Applications for data access should be submitted to the Danish Health Data Authority (contact: servicedesk@sundhedsdata.dk). Researchers wishing to access and use the data for research purposes must meet the credentialing requirements detailed on the Authority’s website: https://sundhedsdatastyrelsen.dk/da/english/health_data_and_registers/research_services. To access data from DCCG, applications should be made as specified on the DCCG website (https://dccg.dk/om-databasen/) under the section ‘Om databasen.’

Code availability

Analyses were performed with R (v.4.2.0) using packages: PatientLevelPrediction (v.6.3.6), CohortGenerator (v.0.8.1), DatabaseConnector (v.6.3.2), SqlRender (v.1.17.0), FeatureExtraction (v.3.4.0), Andromeda (v.0.6.6), reticulate (v.1.40.0), survival (v.3.4-0), stringr (v.1.5.1), tidyverse (v.2.0.0), tidymodels (v.1.0.0), table1 (v.1.4.2), boot (v.1.3-28), viridis (v.0.6.5), pROC (v.1.18.5), ggpubr (v.0.6.0), grid (v.4.2.0), gridExtra (v.2.3), ggsurvfit (v.0.3.1), data.table (v.1.16.4), cowplot (v.1.1.3), ggcorrplot (v.0.1.4), broom (v.1.0.6), purrr (v.1.0.2), scales (v.1.3.0), models (v.2.18.1.1), glue (v.1.8.0), fitdistrplus (v.1.2-1), MASS (v.7.3-58.1), lubridate (v.1.9.3), zoo (v.1.8-12), expm (v.0.999-6), rlang (v.1.1.4) and gtools (v.3.9.5). Covariate definitions and custom code are available via GitHub at https://github.com/CenterForSurgicalScienceDenmark/aidSurg/.

References

Nepogodiev, D. et al. Global burden of postoperative death. Lancet 393, 401 (2019).

Molenaar, C. J. L. et al. Effect of multimodal prehabilitation on reducing postoperative complications and enhancing functional capacity following colorectal cancer surgery: the PREHAB randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 158, 572–581 (2023).

Bausys, A. et al. Effect of home-based prehabilitation on postoperative complications after surgery for gastric cancer: randomized clinical trial. Br. J. Surg. 110, 1800–1807 (2023).

Wang, B. et al. Prehabilitation program improves outcomes of patients undergoing elective liver resection. J. Surg. Res. 251, 119–125 (2020).

Loftus, T. J. et al. Artificial intelligence and surgical decision-making. JAMA Surg. 155, 148–158 (2020).

Klein, M. F. et al. Validation of the Danish Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG.dk) database—on behalf of the Danish Colorectal Cancer Group. Colorectal Dis. 22, 2057–2067 (2020).

Varghese, C., Harrison, E. M., O’Grady, G. & Topol, E. J. Artificial intelligence in surgery. Nat. Med. 30, 1257–1268 (2024).

Ren, Y. et al. Performance of a machine learning algorithm using electronic health record data to predict postoperative complications and report on a mobile platform. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2211973 (2022).

Agius, R. et al. Deployment and validation of the CLL treatment infection model adjoined to an EHR system. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 147 (2024).

Schuemie, M. et al. Health-analytics data to evidence suite (HADES): open-source software for observational research. Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 310, 966–970 (2024).

Van Der Bij, G. J. et al. The perioperative period is an underutilized window of therapeutic opportunity in patients with colorectal cancer. Ann. Surg. 249, 727–734 (2009).

Ludbrook, G. L. The hidden pandemic: the cost of postoperative complications. Curr. Anesthesiol. Rep. 12, 1–9 (2022).

George, E. L. et al. Association between patient frailty and postoperative mortality across multiple noncardiac surgical specialties. JAMA Surg. 156, e205152 (2021).

Cambriel, A. et al. Impact of preoperative uni- or multimodal prehabilitation on postoperative morbidity: meta-analysis. BJS Open 7, zrad129 (2023).

Fernainy, P. et al. Rethinking the pros and cons of randomized controlled trials and observational studies in the era of big data and advanced methods: a panel discussion. BMC Proc. 18, 1 (2024).

Sperrin, M. et al. Using marginal structural models to adjust for treatment drop-in when developing clinical prediction models. Stat. Med. 37, 4142–4154 (2018).

van Geloven, N. et al. Prediction meets causal inference: the role of treatment in clinical prediction models. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 35, 619–630 (2020).

Collins, G. S. et al. Evaluation of clinical prediction models (part 1): from development to external validation. Br. Med. J. 384, e074819 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Comparison of the effects of imputation methods for missing data in predictive modelling of cohort study datasets. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 24, 41 (2024).

Ingeholm, P., Gögenur, I. & Iversen, L. H. Danish colorectal cancer group database. Clin. Epidemiol. 8, 465–468 (2016).

Pottegård, A. et al. Data resource profile: the Danish national prescription registry. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 798 (2017).

Arendt, J. F. H. et al. Existing data sources in clinical epidemiology: laboratory information system databases in Denmark. Clin. Epidemiol. 12, 469–475 (2020).

Schmidt, M. et al. The Danish National patient registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin. Epidemiol. 7, 449–490 (2015).

Marc Overhage, J., Ryan, P. B., Reich, C. G., Hartzema, A. G. & Stang, P. E. Validation of a common data model for active safety surveillance research. JAMIA 19, 54–60 (2012).

Reich, C. et al. OHDSI standardized vocabularies—a large-scale centralized reference ontology for international data harmonization. JAMIA 31, 583–590 (2024).

Blacketer, C., Defalco, F. J., Ryan, P. B. & Rijnbeek, P. R. Increasing trust in real-world evidence through evaluation of observational data quality. J. Am. Med Inf. Assoc. 28, 2251–2257 (2021).

Harris, P. A. et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inf. 42, 377–381 (2009).

Heidari, S., Babor, T. F., Castro, P., Tort, S. & Curno, M. Sex and gender equity in research: rationale for the SAGER guidelines and recommended use. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 1, 2 (2016).

Pedersen, C. B., Gøtzsche, H., Møller, J. Ø. & Mortensen, P. B. The Danish civil registration system. Scand. J. Public Health 39, 22–25 (2011).

Bojesen, R. D., Degett, T. H., Dalton, S. O. & Gögenur, I. High World Heath Organization performance status is associated with short- and long-term outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery: a nationwide population-based study. Dis. Colon Rectum 64, 851–860 (2021).

Ose, I. et al. The association of postoperative morbidity and age on 5-year survival after colorectal surgery in the elderly population: a nationwide cohort study. Colorectal Dis. 26, 899–915 (2024).

Clavien, P. A. et al. The Clavien–Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann. Surg. 250, 187–196 (2009).

Reps, J. M., Schuemie, M. J., Suchard, M. A., Ryan, P. B. & Rijnbeek, P. R. Design and implementation of a standardized framework to generate and evaluate patient-level prediction models using observational healthcare data. JAMIA 25, 969–975 (2018).

Riley, R. D. et al. Calculating the sample size required for developing a clinical prediction model. Br. Med. J. 368, m441 (2020).

Suchard, M. A., Simpson, S. E., Zorych, L., Ryan, P. & Madigan, D. Massive parallelization of serial inference algorithms for a complex generalized linear model. ACM Trans. Model. Comput. Simul. 23, 1–17 (2013).

James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning, Vol. 44 (Springer US, 2021).

Van Calster, B. et al. A calibration hierarchy for risk models was defined: from utopia to empirical data. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 74, 167–176 (2016).

Collins, G. S. et al. TRIPOD+AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. Br. Med. J. 385, e078378 (2024).

Computerome. www.computerome.dk/ (2024).

EUR-Lex Document 32017R0745. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:02017R0745-20240709 (2024).

Gustafsson, U. O. et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colorectal surgery: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS®) society recommendations: 2018. World J. Surg. 43, 659–695 (2019).

Slade, S. C., Dionne, C. E., Underwood, M. & Buchbinder, R. Consensus on exercise reporting template (CERT): explanation and elaboration statement. Br. J. Sports Med. 50, 1428–1437 (2016).

Hoffmann, T. C. et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. Br. Med. J. 348, g1687 (2014).

Vejledning til perioperativ væskebehandling. https://dasaim.dk/guides/vejledning-til-perioperativ-vaeskebehandling/ (2024).

Bojesen, R. D. et al. Effect of modifying high-risk factors and prehabilitation on the outcomes of colorectal cancer surgery: controlled before and after study. BJS Open 6, zrac029 (2022).

Bojesen, R. D. et al. The dynamic effects of preoperative intravenous iron in anaemic patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 23, 2550–2558 (2021).

Bojesen, R. D. et al. Fit for Surgery—feasibility of short-course multimodal individualized prehabilitation in high-risk frail colon cancer patients prior to surgery. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 8, 11 (2022).

Danish Medicines Agency. www.medicinpriser.dk/ (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank all clinical personnel at Zealand University Hospital who contributed to this study. We acknowledge the Danish Colorectal Cancer Group and the Danish Clinical Quality Program—National Clinical Registries (RKKP) for providing essential data for the project. This research was supported by Aage and Johanne Louis-Hansen’s Foundation (21-2B-8305/L276 and 23-2B-14410, I.G.), Novo Nordisk Foundation/Data Science Infrastructure grant (NNF21OC0069821, I.G.), Agency for Digital Government (2019–6159, I.G.) and Interreg ØKS (6.3.3-A 2022-4884, I.G.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.W.R., I.O., M.G., L.P.K.A., A.E.T., R.D.B., R.P.V., S.T.S., I.R., E.A.H., K.M., T.F., M.H.T., M.S., S.K.B., T.K., S.Y.T., N.A.F., L.B.H., J.R.E. and I.G. Methodology: A.W.R., I.O., M.G., A.E.T., T.K., S.T.S., M.H.R. and I.G. Investigation: A.W.R., I.O., M.G., L.P.K.A., R.D.B., R.P.V., P.W.S., S.E., E.G., C.A., D.S.G., A.A.R., E.C.A., A.T.N., I.K.S., L.M.E.L., X.L.S., O.W.F., H.S.S., I.R., S.T.S., E.A.H., T.F., M.H.T., M.S., S.K.B., S.Y.T., N.A.F., L.B.H., J.R.E. and I.G. Data curation: A.W.R., I.O., M.G., L.P.K.A., R.D.B., R.P.V., P.W.S., S.E., E.G., C.A., D.S.G., A.A.R., E.C.A., A.T.N., I.K.S., L.M.E.L., X.L.S., O.W.F., H.S.S., I.R., E.A.H., T.F., M.H.T., M.S., S.K.B., S.Y.T., N.A.F., L.B.H. and J.R.E. Writing—original draft: A.W.R., I.O. Writing—review and editing: All authors. Visualization: A.W.R., I.O. and M.G. Supervision: S.K., M.H.R., T.K., J.R.E. and I.G.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

I.G. and M.H.R. are shareholders in Nordic AI Medical ApS—a health technology company that has licensed a medical device incorporating a prediction algorithm to CE mark the algorithm. M.H.R. also serves as a consultant for Nordic AI Medical ApS. I.G., M.H.R., A.W.R. and J.R.E. are named as inventors (not patented) on a medical software developed to support MDT meetings incorporating a prediction model. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Alberto Bardelli, Matthew Sperrin and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Lorenzo Righetto and Saheli Sadanand, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods, TRIPOD+AI checklist and description of interventions.

Supplementary Tables

Table 1. Initial model covariates. Summarizes initial model covariates used in the prediction model. Table 2. Prediction model coefficient. Summarizes the variables and regression coefficient of the final model. Candidate predictors with a regression coefficient of 0 were shrunk to 0 and not included in the final model. Table 3. Model parameter for probabilistic sensitivity analyses. Summarizes the model parameters used in the probabilistic sensitivity analysis. Spade symbol denotes the parameter that was modeled using a Dirichlet distribution. For transitions per risk group/trajectory combination, each state ‘From’ was modeled together using each transition probability as a parameter in the distribution function as αinpatient + αoutpatient + αgeneral practitioner + αno contact to healthcare provider + αdead. For the proportion of patients in risk groups and with complicated trajectories were, the counts were used as input variables for the probability function: αrisk group A, uncomplicated trajectory + αrisk group A, complicated trajectory + αrisk group B, uncomplicated trajectory + αrisk group B, complicated trajectory + αrisk group C, uncomplicated trajectory + αrisk group C, complicated trajectory + αrisk group D, uncomplicated trajectory + αrisk group D, uncomplicated trajectory. Diamond symbols indicate that cost was modeled using gamma distributions, with a shape parameter (κ) of 25 and a scale parameter (θ) of 0.04× the value presented in the table. Costs were presented in 2024 US dollars. Club symbol denotes parameters models with a beta distribution, where shape (α) was 100 × value and shape (β) was 100 − value × 100. Table 4. Diagnoses for health economic evaluation. Overview of included diagnosis codes as base for cost estimations. Table 5. Anatomical therapeutic chemical codes for health economic evaluation. Overview of anatomical therapeutic chemical codes included in cost estimation for prescription medicine.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rosen, A.W., Ose, I., Gögenur, M. et al. Clinical implementation of an AI-based prediction model for decision support for patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery. Nat Med 31, 3737–3748 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03942-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03942-x

This article is cited by

-

KI in der Therapie: Lokal- und Systemtherapie

Die Onkologie (2025)