Abstract

Sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) and the nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (nsMRA) finerenone have each been shown to individually improve heart failure events among patients with heart failure and mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction (HFmrEF/HFpEF). Moreover, the angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) sacubitril/valsartan has been shown to improve outcomes in patients with HFmrEF/HFpEF with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) below normal (<60%). However, the expected benefits of the combined use of these agents with long-term administration are not well defined. Here, in this cross-trial analysis of DELIVER, FINEARTS-HF and PARAGON-HF, combined use of SGLT2i and nsMRA therapies was estimated to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death or first worsening heart failure event by 31% in the overall population (hazard ratio 0.69; 95% confidence interval 0.59–0.81), while combined use of SGLT2i, nsMRA and ARNI therapies was estimated to reduce risk by 39% in patients with HFmrEF/HFpEF and an LVEF <60% (hazard ratio 0.61; 95% confidence interval 0.48–0.77). With long-term use, combined SGLT2i and nsMRA therapies in a 65-year-old patient with HFmrEF/HFpEF, or combined SGLT2i, nsMRA and ARNI therapies in a 65-year-old patient with an LVEF <60%, were projected to afford 3.6 (2.0–5.2) or 4.9 (2.5–7.3) additional years free from cardiovascular death or a heart failure event, respectively. Combined therapy was estimated to result in meaningful gains in event-free survival across a broad age range, from 55 to 85 years. Among patients with HFmrEF and HFpEF, the potential aggregated long-term treatment effects of early combination medical therapy with SGLT2i and nsMRA (and ARNI in selected individuals) are projected to be substantial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

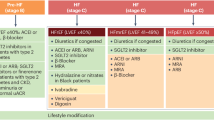

Patients with heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) experience life expectancies that are considerably shorter than their peers of similar ages1. Until recently, the management of HFpEF was largely empirical and limited to diuretics, blood pressure control and comorbidity management. Indeed, before 2023, major clinical practical guidelines offered no class I (strong) recommendation for any specific pharmacotherapy (beyond diuretics) in the treatment of HFpEF. However, since then, the sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) have been shown to improve cardiovascular outcomes and are strongly recommended in patients with HF and mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction (HFmrEF/HFpEF), that is, a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) >40% (refs. 2,3). A trial of the nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (nsMRA) finerenone demonstrated its efficacy and safety in this same population, which supported its recent regulatory approval by the US Food and Drug Administration4. In addition, a trial of the angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) sacubitril/valsartan, while narrowly missing its primary endpoint5, suggested efficacy in patients with a LVEF below normal (<60%)6. Smaller trials with shorter-duration follow-up periods have suggested potential early efficacy with incretin-based therapies, but long-term outcomes trials are awaited. As randomized clinical trials tested these therapies individually in trials conducted over an average follow-up of 2–3 years on the background of varying medical therapy regimens, the expected benefits of their combined use when administered long-term are not well defined.

Multiple stakeholders (patients, clinicians, health systems and payors) may be interested in the therapeutic potential of these therapies when used together in the management of this growing population. As such, we first estimated the aggregate relative benefits of SGLT2i and nsMRA in all patients with HFmrEF/HFpEF and the combination of SGLT2i, nsMRA and ARNI in those with HFmrEF/HFpEF and a LVEF <60%. We then projected the potential absolute long-term gains in event-free survival with comprehensive medical therapy.

Results

Relative treatment effects of comprehensive medical therapy

For the main analysis, we derived treatment estimates from 6,263 participants in DELIVER (Dapagliflozin Evaluation to Improve the LIVEs of Patients with Preserved Ejection Fraction Heart Failure) and 6,001 participants in FINEARTS-HF (FINerenone trial to investigate Efficacy and sAfety superioR to placebo in paTientS with Heart Failure) (Table 1). In the subgroup of individuals with LVEF below normal (<60%), we estimated treatment effects from 4,372 participants in DELIVER, 4,846 in FINEARTS-HF and 2,070 in PARAGON-HF (Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ARB Global Outcomes in HF with Preserved Ejection Fraction). These trials evaluated older participants with HF (mean ages 72–73 years), with balanced sex distribution (44–52% women) and a high rate of comorbidities. Background mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) use was 26% in PARAGON-HF and 43% in DELIVER. Background ARNI use was 5% in DELIVER and 9% in FINEARTS-HF. Background SGLT2i use was 1% in PARAGON-HF and 14% in FINEARTS-HF (Table 2). Within each of the trials, serious adverse events were reported at similar frequencies between the study arms. Hypotension (systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg) was more common with finerenone (versus placebo) and ARNI (versus valsartan), and elevated serum potassium >5.5 mmol l−1 was more common with finerenone (versus placebo) (Table 3).

Combination use of SGLT2i and nsMRA was estimated to reduce the risk of the primary endpoint of cardiovascular death or first worsening HF event by 31% in the overall HFmEF/HFpEF population (hazard ratio (HR) 0.69; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.59–0.81). In individuals with an LVEF below normal (<60%), the combined use of SGLT2i, nsMRA and ARNI was estimated to reduce risk by 39% (HR 0.61; 95% CI 0.48–0.77) (Fig. 1). When considering the effects of ARNI (against a putative placebo), the combination use of SGLT2i, nsMRA and ARNI (versus putative placebo) was estimated to reduce risk by 47% (HR 0.53; 95% CI 0.39–0.71). In the overall population, results were consistent in a sensitivity analysis examining SGLT2i as a class (based on meta-analysis of DELIVER and EMPEROR-Preserved) and MRAs as a class (based on meta-analysis of FINEARTS-HF and TOPCAT) (aggregate HR 0.70; 95% CI 0.61–0.79). In sensitivity analyses, aggregate relative treatment effects remained robust for the composite of all-cause death or worsening HF event (HR 0.76; 95% CI 0.66–0.87) to account for competing risks of mortality and when evaluating the composite of cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization (not considering urgent HF visits) (HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.60–0.84).

Aggregate relative benefits of SGLT2i and nsMRA in the overall population (left) and the combination of SGLT2i, nsMRA, and ARNI in individuals with a LVEF below normal <60% (right). Treatment estimates for individual therapies and their combination are summarized as HRs and 95% CIs. ‘Standard treatment’ in the comparator populations constituted treatment according to the standard of care based on local guidelines, but did not mandate any specific pharmacotherapy. For the main analysis, we derived treatment estimates from 6,263 participants in DELIVER and 6,001 participants in FINEARTS-HF. In the subgroup of individuals with LVEF below normal (<60%), we estimated treatment effects from 4,372 participants in DELIVER, 4,846 in FINEARTS-HF and 2,070 in PARAGON-HF.

Applying guideline-concordant LVEF designations, comprehensive medical therapy was estimated to reduce the primary endpoint by 32% (HR 0.68; 95% CI 0.56–0.83) in those with HFpEF (LVEF ≥50%) with SGLT2i and nsMRA and by 42% (HR 0.58; 95% CI 0.40–0.85) in those with HFmrEF (LVEF 40–50%) with SGLT2i, nsMRA and ARNI.

3-Year absolute risk reductions and number-needed-to-treat

We estimated event-free survival in 1,754 participants with HFmrEF/HFpEF in the control arm of the DELIVER trial (main analysis) and in the subset of 1,123 participants with HFmrEF/HFpEF and an LVEF below normal (<60%). Mean age was 72.5 ± 9.0 years, and 818 (46.6%) were women (Extended Data Table 1).

In the overall HFmrEF/HFpEF population, over a median within-trial follow-up of 2.2 years (25th–75th percentiles 1.5–2.7 years), 330 primary events were observed with a corresponding event rate of 9.1 (95% CI 8.1–10.1) per 100 patient-years. Based on the observed annualized event rate in the control group of the DELIVER trial, the estimated range of aggregate absolute risk reductions over 3 years of comprehensive medical therapy was 4–9%, corresponding to a number-needed-to-treat of 11–25 to prevent one primary endpoint event.

In the LVEF-below-normal subpopulation, over a median within-trial follow-up of 2.3 years (25th–75th percentiles 1.5–2.8 years), 211 primary events were observed with a corresponding event rate of 9.1 (95% CI 7.9–10.4). With 3 years of comprehensive medical therapy, the absolute risk reductions would range from 5% to 12%, corresponding to a number-needed-to-treat of 9–20 to prevent one primary endpoint event.

Long-term projections of event-free survival gains

In the overall population, forecasted long-term survival free from the primary endpoint (cardiovascular death or worsening HF event) was estimated to be 10.7 years (95% CI 9.3–12.1) in placebo-treated participants on standard therapy and 14.3 years (95% CI 12.7–15.9) with comprehensive treatment with SGLT2i and nsMRA. We estimated comprehensive medical therapy to provide 3.6 (2.0–5.2) additional years free from cardiovascular death or HF event in a 65-year-old participant (Fig. 2). Event-free survival gains remained substantial in sensitivity analyses assuming subadditive treatment effects of therapies (Extended Data Table 2) and waning efficacy of comprehensive medical therapy over time (Extended Data Table 3). Meaningful gains in event-free survival were observed across a broad age range (Fig. 3) from 1.5 (0.9–2.1) additional years in an 85-year-old to 4.1 (2.2–6.1) additional years in a 55-year-old. In a 65-year-old HFmrEF/HFpEF patient with LVEF below normal (<60%), comprehensive treatment with SGLT2i, nsMRA and ARNI was estimated to afford 4.9 (2.5–7.3) years free from cardiovascular death or HF event.

Kaplan–Meier estimated curves for patients starting at 65 years of age for survival free from the primary endpoint (cardiovascular death or worsening HF event) in the overall HFmrEF/HFpEF population (left) and in individuals with HFmrEF/HFpEF with a LVEF below normal <60% (right). Residual event-free lifespan was estimated using the area under the survival curve up to a maximum of 100 years of age.

a, Estimated mean survival free from the primary endpoint in the DELIVER control group and the simulated comprehensive medical therapy group for every age between 55 and 85 years in the overall population with HFmrEF/HFpEF (left) or patients with HFmrEF/HFpEF and LVEF below normal (<60%) (right). b, Treatment differences (data points), smoothed estimates (solid lines) and 95% CI of the smoothed estimates (dashed lines) are displayed for mean event-free survival with comprehensive medical therapy after application of a locally weighted scatterplot smoothing procedure. Data are shown for the overall population with HFmrEF/HFpEF (left) or patients with HFmrEF/HFpEF and LVEF below normal (<60%) (right).

Discussion

The global prevalence of HFpEF is projected to continue rising7, and individuals living with the disease have a guarded prognosis and face a high burden of hospitalizations and healthcare encounters1. As such, extending event-free survival represents a core treatment goal in this high-risk population. In the adjacent population of HF with reduced ejection fraction, we previously estimated that comprehensive medical therapy with four therapies (targeting five distinct pathways) with ARNI, β-blocker, MRA and SGLT2i could afford over 6 years of additional event-free survival in a 65-year-old compared with conventional medical therapy (consisting of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker and β-blocker)8. This ‘pillar-based’ comprehensive medical therapy approach has now been embraced by contemporary clinical practice guidelines and represents the new standard of care globally for HFrEF9,10.

HFpEF is recognized to be a systemic syndrome with both myocardial dysfunction and peripheral abnormalities that contribute to disease progression11. Similar to HFrEF, combining multiple therapies targeting distinct pathophysiologic mechanisms may most comprehensively attenuate risks of morbidity and mortality. The SGLT2i represented the first class of therapies (beyond diuretics) that have been strongly recommended as a class I guideline recommendation across the full spectrum of LVEF, including in HFpEF9. The recent FINEARTS-HF trial4 demonstrated that a second therapy, the nsMRA finerenone, is beneficial in improving outcomes in patients with HFmrEF/HFpEF, including among those already treated with an SGLT2i. The US Food and Drug Administration has since approved finerenone for the management of patients with HF and an LVEF ≥40%. The ARNI sacubitril/valsartan, which targets both the renin–angiotensin system and the natriuretic peptide axis, appears to be most beneficial in those with LVEF below normal5,6 and is now approved for use in many countries worldwide for this indication.

Compared with standard care (which encompassed management of congestion and comorbidities such as hypertension), comprehensive medical therapy inclusive of SGLT2i and nsMRA was estimated to reduce risks of cardiovascular death or worsening HF events by over 30%, and the further addition of ARNI among individuals with an LVEF below normal was estimated to reduce risks of clinical events by nearly 40%. Previous cross-trial analyses were limited to estimating the relative treatment benefits with comprehensive medical therapy without offering perspective on potential absolute treatment gains, especially over a long-term horizon12. Over 3 years, the estimated absolute risk reduction ranged from 4% to 9%, corresponding to a number-needed-to-treat of 11–25 to prevent a clinical event. Over a lifetime horizon, we estimated that comprehensive medical therapy would substantially extend event-free survival in the overall population and in those with LVEF below normal. As younger individuals with HF have longer disease duration and expected residual lifespan, estimated gains in event-free survival with comprehensive medical therapy were greatest in this population. However, across a broad age range, including among people aged 85 years and older, we forecasted meaningful absolute gains in event-free survival. Taken together, these cross-trial data analyses summarize important therapeutic advances in recent years and serve as a reference for relative and absolute gains that might be expected with comprehensive medical therapy.

The first central assumption in our study was that each individual therapy provides additive benefits in patients with HFmrEF/HFpEF. Several lines of evidence suggest that this is an acceptable analytic assumption. First, each of the therapies evaluated has a distinct mechanism of action with no known pharmacological interactions. Second, subgroup analyses from pivotal randomized clinical trials have shown that the benefits of one therapy do not appear attenuated based on background treatment regimens13,14,15, suggesting complementary protection against clinical events. However, we acknowledge that background use of these therapies was incomplete, potentially limiting the power to detect heterogeneity if indeed it was present. Third, recent trials have directly tested the combined use of SGLT2i and MRAs in patients with HFpEF and separately in individuals with chronic kidney disease and shown that combination therapy affords incremental and additive effects on markers of cardiovascular and kidney health16,17. Reassuringly, even when assuming subadditive benefits of these therapies, the long-term gains in event-free survival are projected to be substantial.

The second central assumption was that the therapeutic effects observed during each trial would be sustained during lifetime use of therapies. Clinical trials of HF therapies are often conducted with average follow-up durations of 2–3 years; however, guidelines recommend the long-term continuation of these therapies for much longer treatment horizons, often indefinitely. We developed and validated a methodology to project within-trial observations to estimate long-term disease trajectories, assuming stable treatment effects over time18,19. However, adherence in real-world clinical care settings is known to be lower than during the conduct of clinical trials.

The clinical benefits of both SGLT2i and nsMRA have been shown to attenuate even after short-term drug interruption (within 30 days)20,21. However, clinically relevant gains in long-term event-free survival are expected even when assuming waning efficacy of comprehensive medical therapy over time. However, we did not consider other critical issues regarding the long-term use of therapies, including costs, ongoing access, treatment complexity and polypharmacy. These factors should be considered in the overall assessment of the risks and benefits of comprehensive medical therapy when applying these summary efficacy data to clinical practice.

The final central assumption is that the long-term benefits projected in this cross-trial analysis would translate to clinically relevant benefits when implemented in ‘real-world’ settings. Participants were carefully selected according to specific eligibility criteria in each trial, and in PARAGON-HF, patients were required to tolerate half-target doses of each of the study drugs before randomization5. We considered treatment effects derived from the overall trial populations (aside from the subpopulation with LVEF below normal) as clinical trials have not consistently demonstrated heterogeneity by individual subgroups, but effectiveness of these therapies may still vary in individual patients when applied in usual clinical care settings. Unlike the previous cross-trial analysis in HFrEF8, we projected long-term event-free survival gains with comprehensive medical therapy in HFmrEF/HFpEF but did not consider additive effects on mortality outcomes as none of the individual trials demonstrated significant benefits on overall or cardiovascular mortality. In light of these considerations, we intentionally made conservative analytic choices in our long-term projections and subjected our findings to a range of sensitivity analyses to support their robustness.

While we focused on the aggregate benefits that may be realized with complete implementation of these therapies, safety and tolerability cannot be ignored when considering multidrug regimens in older individuals with HFpEF. Data from pivotal trials support the safety of these therapies when initiated on the background of varying medical regimens3,4,5. In routine clinical practice, however, similar follow-up protocols with close monitoring and frequent study visits may be challenging to replicate. All three classes of therapies are hemodynamically active with potentially additive blood pressure lowering when initiated together16,17. Simultaneous initiation of MRAs and SGLT2i is also known to induce potentially additive acute reductions in kidney function16,17 that appear entirely hemodynamically mediated and not associated with tubular injury or long-term adverse prognosis. MRAs such as finerenone are known to increase serum potassium levels, but early combination with either an SGLT2i22 or ARNI23 (when switched from a renin–angiotensin system inhibitor) may attenuate risks of hyperkalemia, suggesting that these combinations may in fact be safer. It is reassuring that, upon drug cessation, the early changes in hemodynamics, kidney function and potassium are fully reversible17,21. Although initial data from implementation trials24 suggest that the rapid, sequential initiation of multidrug regimens is generally safe, a more gradual, stepwise approach may be necessary for patients predicted to have poorer tolerability (such as those who are frail or clinically unstable).

The therapeutic landscape of HFpEF continues to rapidly evolve. We attempted to consider the totality of available evidence, including major positive trials powered for clinical outcomes in broad populations of HFpEF, that have supported regulatory approvals for the management of this condition. There has been considerable interest in the potential role of obesity-targeted therapies, such as the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and related compounds, in the management of HFpEF. In fact, three recent trials with sample sizes of approximately 500–750 participants have demonstrated clinical benefits25,26,27. However, while awaiting larger trials (such as NCT07037459), we have not considered these therapies in the cross-trial analysis given the exclusive focus on a specific phenotype of HFpEF (with a body mass index ≥30 kg m−2), limited number of clinical events (<100 events in each of the trials completed thus far) and relatively short duration of follow-up (1–2 years). Similarly, we did not consider use of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors alone, despite their common use in this population for the management of comorbidities (such as hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease and chronic kidney disease), as primary trials did not meet their primary endpoints28,29 and these therapies are not approved for this indication.

Among patients with HFmrEF and HFpEF, the anticipated aggregate long-term treatment effects of early comprehensive medical therapy with SGLT2i and nsMRA (and ARNI in selected individuals) are projected to be substantial. These data underscore the urgent need to bolster global implementation efforts to improve the use of medical therapies in HFmrEF/HFpEF, a population with previously limited therapeutic options.

Methods

In this cross-trial analysis, we identified pivotal trials that supported the regulatory evaluation of therapies approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (as of August 2025) for the management of HFmrEF/HFpEF. We leveraged individual participant-level data that we had direct access to to represent each class of therapies: SGLT2i (dapagliflozin in DELIVER), nsMRA (finerenone in FINEARTS-HF) and ARNI (sacubitril/valsartan in PARAGON-HF). Table 1 summarizes key design features of each trial. All trials were assessed as high quality with a low risk of bias (Extended Data Table 4). The primary results of each trial have been previously published, and the study protocols and statistical analysis plans are publicly available3,4,5. All participants provided informed consent, and trial protocols were approved by local institutional review boards or ethics committees.

DELIVER

From 2018 to 2021, the DELIVER (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03619213) trial3 randomly assigned 6,263 adults ≥40 years with symptomatic HF and an LVEF >40% to dapagliflozin 10 mg once daily or matching placebo. All participants were required to have evidence of structural heart disease and elevated natriuretic peptide levels. Median follow-up was 2.3 years.

FINEARTS-HF

From 2020 to 2023, the FINEARTS-HF (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04435626) trial4 randomly assigned 6,001 adults ≥40 years with symptomatic HF and an LVEF ≥40% to finerenone or matching placebo titrated to target doses of 20 mg or 40 mg (depending on baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate). All participants were required to have evidence of structural heart disease and elevated natriuretic peptide levels. Median follow-up was 2.7 years.

PARAGON-HF

From 2014 to 2016, the PARAGON-HF (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01920711) trial5 randomly assigned 4,796 adults ≥18 years with symptomatic HF and an LVEF ≥45% to the ARNI sacubitril/valsartan (target dose, 97 mg of sacubitril with 103 mg of valsartan twice daily) versus the angiotensin receptor blocker valsartan (target dose, 160 mg twice daily). Only participants who tolerated half target doses of both study medications during a single-blind run-in phase were randomized. All participants were required to have evidence of structural heart disease and elevated natriuretic peptide levels. Median follow-up was 2.9 years.

Clinical outcomes

Our primary endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular death or worsening HF event (which included both a hospitalization for HF and an urgent ambulatory encounter for HF requiring intravenous HF therapies). All potential HF events and deaths were prospectively collected and adjudicated by blinded clinical endpoint committees.

Statistical analysis

We first estimated the aggregate relative effects of comprehensive medical therapy based on individual treatment effects observed in each component trial. We used established methods of indirect comparisons, which are commonly applied in putative placebo assessments30. The accompanying 95% CI was estimated by the square root of the sum of the squared standard errors of the logarithmic HRs of the individual trial treatment effects. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate all time-to-first composite endpoints with trial-specific stratification terms as prespecified in each trial protocol: DELIVER (diabetes status)3, FINEARTS-HF (geographic region and LVEF <60% or ≥60%)4, and PARAGON-HF (geographic region)5. No covariate adjustment was made.

We considered comprehensive medical therapy as the combined use of SGLT2i and nsMRA for the overall population. As ARNI is indicated in many countries worldwide specifically for the treatment of patients with HF and LVEF below normal, we considered comprehensive medical therapy as the combined use of SGLT2i, nsMRA and ARNI for patients with an LVEF <60%. As PARAGON-HF was an active-controlled trial, we used the same methods of indirect comparisons to estimate the treatment effects of ARNI if it was instead compared against a putative placebo30. To do so, participant-level data were accessed from the CHARM-Preserved (Candesartan Cilexietil in Heart Failure Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity) trial, which tested the angiotensin receptor blocker, candesartan (target dose 32 mg once daily) against placebo among 3,023 patients with symptomatic HF and LVEF >40% (ref. 28). As urgent HF visits were not collected or adjudicated in CHARM-Preserved, the endpoint of cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization was considered instead. We additionally conducted alternative segmenting aligned with contemporary guideline designations of LVEF9,10 and separately evaluated HFmrEF (LVEF between 40% and 50%) and HFpEF (LVEF of 50% or greater). The comparator populations were individuals treated according to the standard of care based on local guidelines, but did not mandate any specific pharmacotherapy.

We then projected the long-term absolute event-free survival gains by applying the imputed treatment effects of comprehensive medical therapy to the control group of the DELIVER trial. To consider individuals untreated with these therapies, we excluded individuals already treated with an ARNI or an MRA at baseline (n = 1,378). We leveraged validated actuarial (age-based) methods18,19 that reshape the follow-up horizon from considering time since randomization to evaluating age instead. At every age between 55 years and 85 years, we calculated nonparametric Kaplan–Meier estimates of residual survival free from the primary endpoint. Projected event-free survival was then estimated as the area under the survival curve (up to a maximum of 100 years). We separately estimated long-term event-free survival as observed in individuals in the DELIVER control arm (comparator group) and simulated if treated with comprehensive medical therapy. As there were no observed age-by-treatment interactions in any of the component trials31,32,33,34,35, the difference in areas under the survival curves represented the gains in event-free survival with comprehensive medical therapy at any given age of starting therapy. We additionally applied the lower and upper bounds of the 95% CI around the relative treatment effects to the DELIVER control group to provide a range of uncertainty of our estimates. For display purposes, event-free survival gains across the age range were smoothed after application of a locally weighted scatterplot smoothing procedure.

Sensitivity analyses

We conducted a series of sensitivity and supplemental analyses to test the robustness of our cross-trial analysis. First, instead of considering DELIVER data alone, data from a meta-analysis of the two large SGLT2i outcomes trials in HFmrEF/HFpEF were used instead to summarize treatment effects of SGLT2i32. Similarly, instead of using FINEARTS-HF alone, data from a meta-analysis of FINEARTS-HF and a previous large HFmrEF/HFpEF outcomes trial of the steroidal MRA spironolactone were used instead to summarize treatment effects of MRA33. Second, we estimated the treatment effects of comprehensive medical therapy without making the assumption that two therapies when used together would provide fully additive effects. To do so, we assumed that the treatment effects of nsMRA may be 50%, 75% and 90% of its full efficacy when added to an SGLT2i. In each scenario, we multiplied the beta coefficient of the HR for nsMRA by the percentage of subadditive assumed effect; the resulting estimates were then inputted into the indirect comparison calculations to derive the treatment effects of comphrensive therapy. Third, we evaluated the long-term event-free survival gains of comprehensive medical therapy assuming declining or waning efficacy over time. Specifically, we assumed a yearly decline of 2%, 5% and 10% (compared with the previous year) in the efficacy of comprehensive medical therapy. Fourth, to account for potential competing risks of mortality, we evaluated comprehensive treatment effects on the composite endpoint of all-cause death or worsening HF event. Finally, to address concerns that urgent HF visits may not be as clinically meaningful as the other components of the composite endpoint, we evaluated a modified composite of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for HF, excluding urgent HF visits. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA, and P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All trial funders are committed to sharing access to patient-level data and supporting clinical documents from eligible studies. Trial data availability is subject to the separate criteria and processes of AstraZeneca (https://astrazenecagrouptrials.pharmacm.com/ST/Submission/Disclosure), Bayer (https://vivli.org/ourmember/bayer/) and Novartis (https://www.novartis.com/sites/novartis_com/files/clinical-trial-data-transparency.pdf).

References

Shah, K. S. et al. Heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction: 5-year outcomes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 70, 2476–2486 (2017).

Anker, S. D. et al. Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 1451–1461 (2021).

Solomon, S. D. et al. Dapagliflozin in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 1089–1098 (2022).

Solomon, S. D. et al. Finerenone in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 391, 1475–1485 (2024).

Solomon, S. D. et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 1609–1620 (2019).

Solomon, S. D. et al. Sacubitril/valsartan across the spectrum of ejection fraction in heart failure. Circulation 141, 352–361 (2020).

Martin, S. S. et al. 2025 heart disease and stroke statistics: a report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation 151, e41–e660 (2025).

Vaduganathan, M. et al. Estimating lifetime benefits of comprehensive disease-modifying pharmacological therapies in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a comparative analysis of three randomised controlled trials. Lancet 396, 121–128 (2020).

McDonagh, T. A. et al. 2023 focused update of the 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 44, 3627–3639 (2023).

Heidenreich, P. A. et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 145, e895–e1032 (2022).

Campbell, P., Rutten, F. H., Lee, M. M., Hawkins, N. M. & Petrie, M. C. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: everything the clinician needs to know. Lancet 403, 1083–1092 (2024).

Vaduganathan, M. et al. Estimating the benefits of combination medical therapy in heart failure with mildly reduced and preserved ejection fraction. Circulation 145, 1741–1743 (2022).

Yang, M. et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure with mildly reduced and preserved ejection fraction treated with a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist or sacubitril/valsartan. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 24, 2307–2319 (2022).

Vaduganathan, M. et al. Effects of the nonsteroidal MRA finerenone with and without concomitant SGLT2 inhibitor use in heart failure. Circulation 151, 149–158 (2025).

Jering, K. S. et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist use in PARAGON-HF. JACC Heart Fail. 9, 13–24 (2021).

Ferreira, J. P. et al. Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor with and without an aldosterone antagonist for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the SOGALDI-PEF trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 86, 320–333 (2025).

Agarwal, R. et al. Finerenone with empagliflozin in chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2410659 (2025).

Claggett, B. et al. Estimating the long-term treatment benefits of sacubitril–valsartan. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 2289–2290 (2015).

Ferreira, J. P. et al. Within trial comparison of survival time projections from short-term follow-up with long-term follow-up findings. ESC Heart Fail. 9, 3655–3658 (2022).

Vaduganathan, M. et al. Blinded withdrawal of finerenone after long-term treatment in the FINEARTS-HF trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 86, 396–399 (2025).

Packer, M. et al. Blinded withdrawal of long-term randomized treatment with empagliflozin or placebo in patients with heart failure. Circulation 148, 1011–1022 (2023).

Neuen, B. L. et al. Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and risk of hyperkalemia in people with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomized, controlled trials. Circulation 145, 1460–1470 (2022).

Desai, A. S. et al. Reduced risk of hyperkalemia during treatment of heart failure with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists by use of sacubitril/valsartan compared with enalapril: a secondary analysis of the PARADIGM-HF trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2, 79–85 (2017).

Mebazaa, A. et al. Safety, tolerability and efficacy of up-titration of guideline-directed medical therapies for acute heart failure (STRONG-HF): a multinational, open-label, randomised, trial. Lancet 400, 1938–1952 (2022).

Packer, M. et al. Tirzepatide for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 392, 427–437 (2025).

Kosiborod, M. N. et al. Semaglutide in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 389, 1069–1084 (2023).

Kosiborod, M. N. et al. Semaglutide in patients with obesity-related heart failure and type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 390, 1394–1407 (2024).

Yusuf, S. et al. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved Trial. Lancet 362, 777–781 (2003).

Massie, B. M. et al. Irbesartan in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 2456–2467 (2008).

Vaduganathan, M. et al. A putative placebo analysis of the effects of sacubitril/valsartan in heart failure across the full range of ejection fraction. Eur. Heart J. 41, 2356–2362 (2020).

Peikert, A. et al. Efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction according to age: the DELIVER trial. Circ. Heart Fail. 15, e010080 (2022).

Vaduganathan, M. et al. SGLT-2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure: a comprehensive meta-analysis of five randomised controlled trials. Lancet 400, 757–767 (2022).

Jhund, P. S. et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in heart failure: an individual patient level meta-analysis. Lancet 404, 1119–1131 (2024).

Chimura, M. et al. Finerenone improves outcomes in patients with heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction irrespective of age: a prespecified analysis of FINEARTS-HF. Circ. Heart Fail. 17, e012437 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Effect of sacubitril/valsartan in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction across the age spectrum in PARAGON-HF. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 27, 96–106 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The DELIVER trial was funded by AstraZeneca. The FINEARTS-HF trial was funded by Bayer. The PARAGON-HF trial was funded by Novartis. The trial sponsors had no role in the design, analysis, interpretation, writing of the manuscript or decision to submit this cross-trial analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.V. and S.D.S. conceived of and designed the study and had full access to all the data in the study. M.V., S.C. and B.L.C. did the analysis. M.V. drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to data interpretation and writing of the final version of the manuscript, and all authors were responsible for the decision to submit the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.V. has received research grant support, served on advisory boards or had speaker engagements with Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, American Regent, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer AG, Baxter Healthcare, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cytokinetics, Esperion, Fresenius Medical Care, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Milestone Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pharmacosmos, Recordati, Relypsa, Roche Diagnostics, Sanofi and Tricog Health, and participates on clinical trial committees for studies sponsored by Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer AG, Boehringer Ingelheim, Galmed, Impulse Dynamics, Novartis, Occlutech and Pharmacosmos. B.L.C. has received personal consulting fees from Alnylam, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cardior, Cardurion, Corvia, CVRx, Eli Lilly, Intellia and Rocket and has served on a DSMB for Novo Nordisk. S.C. is supported by the Canadian Child’s Scholarship from the Libin Institute of Alberta/Cumming School of Medicine. A.S.D. has received institutional research grants (to Brigham and Women’s Hospital) from Abbott, Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Novartis and Pfizer as well as personal consulting fees from Abbott, Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biofourmis, Boston Scientific, Medpace, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, Parexel, Porter Health, Regeneron, River2Renal, Roche, Veristat, Verily and Zydus. P.S.J. reports speakers’ fees from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Alkem Metabolics, ProAdWise Communications and Sun Pharmaceuticals; advisory board fees from AstraZeneca,Boehringer Ingelheim and Novartis; and research funding from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Analog Devices Inc and Roche Diagnostics. P.S.J.’s employer, the University of Glasgow, has been remunerated for clinical trial work from AstraZeneca, Bayer AG, Novartis and Novo Nordisk. P.S.J. is also Director of GCTP Ltd. O.V. has received grants from AstraZeneca and Cardior, and institutional research support from Bayer and Cardurion. B.M. has received advisory board fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Biotronik, Boehringer Ingelheim, CSL Behring, Daiichi-Sankyo, Duke Clinical Institute, Medtronic and Novartis. B.M.’s institution has received fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Biotronik, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, CSL Behring, Daiichi-Sankyo, Duke Clinical Institute, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Novartis, Terumo and Vifor Pharma. F.M. has received consultation fees and research grants from AstraZeneca, Baliarda, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Gador, Milestone, Novartis, Pfizer and St Lukes University. J.C.-C. has received grants from Novartis, Vifor Pharma, AstraZeneca and Orion Pharma and has received personal fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Vifor Pharma, Novartis, AstraZeneca and Orion Pharma. J.F.K.S. has served on advisory boards for and received consulting fees and honoraria from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Hypera, Medtronic, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Novo Nordisk and Viatris. S.J.S. has received research grants from NIH (U54 HL160273, X01 HL169712, R01 HL140731 and R01 HL149423), AHA (24SFRNPCN1291224), AstraZeneca, Corvia, and Pfizer and consulting fees from Abbott, Alleviant, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Aria CV, Axon Therapies, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cyclerion, Cytokinetics, Edwards Lifesciences, Eidos, Imara, Impulse Dynamics, Intellia, Ionis, Lilly, Merck, MyoKardia, Novartis, Novo Nordisk,Pfizer, Prothena, Regeneron, Rivus, Sardocor, Shifamed, Tenax, Tenaya and Ultromics. C.S.P.L. has received research support from Novo Nordisk and Roche Diagnostics; has received consulting fees from Alleviant Medical, Allysta Pharma, AnaCardio AB, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biopeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, CardioRenal, CPC Clinical Research, Eli Lilly, Impulse Dynamics, Intellia Therapeutics, Ionis Pharmaceutical, Janssen Research & Development LLC, Medscape/WebMD Global LLC, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Prosciento Inc, Quidel Corporation, Radcliffe Group Ltd., Recardio Inc, ReCor Medical, Roche Diagnostics, Sanofi, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics and Us2.ai; and is a co-founder and non-executive director of Us2.ai. F.Z. reports personal fees from 89Bio, Abbott, Acceleron, Applied Therapeutics, Bayer, Betagenon, Boehringer, BMS, CVRx, Cambrian, Cardior, Cereno pharmaceutical, Cellprothera, CEVA, Inventiva, KBP, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Owkin, Otsuka, Roche Diagnostics, Northsea and Us2.ai, having stock options at G3Pharmaceutical and equities at Cereno, Cardiorenal and Eshmoun Clinical research and being the founder of Cardiovascular Clinical Trialists. K.F.D. reports that his employer, the University of Glasgow, has been remunerated by AstraZeneca for his work on clinical trials, and he has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pharmacosomos and Translational Medicine Academy; has served on advisory boards or performed consultancy for FIRE-1, Us2.ai and Bayer AG; holds stock in Us2.ai; has served on a Clinical Endpoint Committee for Bayer AG; and has received research grant support (paid to his institution) from AstraZeneca, Roche, Novartis and Boehringer Ingelheim. J.J.V.M. reports payments through Glasgow University from work on clinical trials, consulting and grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Cardurion, Cytokinetics, GSK and Novartis; personal consultancy fees from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals,Amgen, AnaCardio, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Berlin Cures, BMS, Cardurion, Cytokinetics, IonisPharmaceuticals, Novartis, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, River 2 Renal Corp., British Heart Foundation, National Institute for Health – National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NIH-NHLBI), Boehringer Ingelheim, SQ Innovations and Catalyze Group; and personal lecture fees from Abbott, Alkem Metabolics, AstraZeneca, Blue Ocean Scientific Solutions Ltd., Boehringer Ingelheim, Canadian Medical and Surgical Knowledge, Emcure Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Eris Lifesciences, European Academy of CME, Hikma Pharmaceuticals, Imagica Health, Intas Pharmaceuticals, J.B. Chemicals & Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Lupin Pharmaceuticals, Medscape/Heart.Org., ProAdWise Communications, Radcliffe Cardiology, Sun Pharmaceuticals, The Corpus, Translation Research Group and Translational Medicine Academy. He serves on a DSMB for WIRB-CopernicusGroup Clinical Inc, and he is a director of Global Clinical Trial Partners Ltd. S.D.S. has received research grants from Alexion, Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Bellerophon, Bayer, BMS, Boston Scientific, Cytokinetics, Edgewise, Eidos, Gossamer, GSK, Ionis, Lilly, MyoKardia, NIH/NHLBI, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Respicardia, Sanofi Pasteur, Theracos and Us2.ai and has consulted for Abbott, Action, Akros, Alexion, Alnylam, Amgen, Arena, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Cardior, Cardurion, Corvia, Cytokinetics, Daiichi-Sankyo, GSK, Lilly, Merck, Myokardia, Novartis, Roche, Theracos, Quantum Genomics, Janssen, CardiacDimensions, Tenaya, Sanofi Pasteur, Dinaqor, Tremeau, CellProThera, Moderna, American Regent, Sarepta, Lexicon, Anacardio, Akros and Valo.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Chihua Li and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Michael Basson, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vaduganathan, M., Claggett, B.L., Chatur, S. et al. Lifetime benefits of comprehensive medical therapy in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction. Nat Med 32, 325–331 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04037-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04037-3