Abstract

Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) is crucial in precision oncology, yet its real-world utility remains unclear. Here we analyzed data from the Japanese nationwide Center for Cancer Genomics and Advanced Therapeutics database, including clinical and genetic data from 54,185 patients with advanced solid tumors (consisting of 81 common and rare tumor types) who received CGP with a targeted sequencing panel covering 324 genes as part of their clinical care. We assessed the prognostic value of CGP-guided clinical evidence-level classification, showing that alterations predicting response to Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency-approved or Food and Drug Administration-approved therapies and to therapies supported by well-powered studies with expert consensus are detected in 16.6% and 8.1% of patients, respectively, and are associated with better prognosis than those with lower clinical evidence levels. Only 8% of patients receive CGP-guided approved–experimental genomic biomarker-linked therapies, although the proportion has improved over time. Substantial differences were observed across tumor types, with the proportions exceeding 20% in thyroid and lung cancers but remaining below 2% in pancreatic and liver cancers. Tumor-agnostic biomarker analyses reveal that tumor mutational burden (TMB) ≥20 mutations per megabase predicts better outcome across tumor types, regardless of microsatellite instability status, in TMB-high patients receiving pembrolizumab. Conversely, extramammary Pagetʼs disease is exceptionally resistant to pembrolizumab. The large-scale nationwide database allows evaluating inter-tumor type differences and investigating evidence-scarce situations, delineating where CGP offers greater benefit. These real-world findings complement those from clinical trials and prospective sequencing projects regarding CGP, providing valuable information for individualized treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Large-scale clinicogenomic studies using next-generation sequencing (NGS) have revealed the clinical utility of driver alterations as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers and have facilitated the development of molecularly targeted therapies or genomic biomarker-linked therapies. Although a few genomic biomarker-linked therapies, including erlotinib for EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), existed in the pre-NGS era, their development has substantially expanded thereafter1,2. These therapies include not only tumor-type-specific but also tumor-agnostic therapies, such as entrectinib and larotrectinib for NTRK fusions and pembrolizumab for high TMB (TMB-H). The availability of genomic biomarker-linked therapies differs among tumor types: clinically actionable alterations are frequent in lung, breast and thyroid cancers but rare in pancreatic and cervical cancers1,2,3,4.

Companion diagnostic (CDx) assays are critical for selecting appropriate patients for molecularly targeted therapies. Traditionally, immunohistochemistry (IHC) and individual gene testing, such as in situ hybridization (ISH) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR), have been utilized. Recently, with the development of numerous genomic biomarker-linked therapies, the identification of many actionable alterations has become necessary. Thus, NGS-based CGP has been increasingly performed to simultaneously evaluate somatic alterations in hundreds of cancer-related genes1,5. In addition, several CGP assays were approved as CDx for tumor-agnostic indications6,7, including FoundationOne CDx (F1CDx), a targeted sequencing panel covering 324 genes. Therefore, CGP facilitates not only the use of approved genomic biomarker-linked therapies but also the enrollment in clinical trials and the use of off-label drugs.

Large-scale clinical sequencing projects have demonstrated the utility of CGP by showing that a large proportion of patients harbor actionable alterations1,2,8,9. However, CGP has several drawbacks, such as long turnaround time, high cost, unavailability as CDx for many molecularly targeted therapies and limitation of testing timing and hospitals capable of performing CGP1,5. Thus, although several guidelines recommend CGP early in the management of advanced solid tumors10,11, many patients undergo non-NGS-based CDx and related therapies before CGP12,13, resulting in fewer patients receiving CGP-guided genomic biomarker-linked therapies. In addition, although the efficacy of specific genomic biomarker-linked therapies against a subset of tumors with corresponding actionable alterations has been demonstrated in clinical trials, whether the availability of diverse genomic biomarker-linked therapies improves the clinical outcome of the overall patient population receiving CGP remains controversial5,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. Therefore, the actual utility of CGP and its differences among tumor types remain unknown in the real world.

There are several real-world situations where limited evidence exists regarding the clinical utility of CGP. CGP is valuable for detecting tumor-agnostic genomic biomarkers, especially those lacking non-CGP CDx, such as TMB-H and NTRK fusions6. Although these biomarkers and related therapies are approved across all solid tumors, the nature of alterations and tumor histology may affect the efficacy of such therapies. Moreover, although many studies showed the concordance of non-CGP CDx and CGP7,22,23, it remains unclear whether genomic biomarker-linked therapies are effective in patients with discordant results.

In Japan, since 2019, CGP tests have been conducted under the national insurance system for patients with advanced or recurrent solid tumors who have completed standard treatment3,24. Almost all CGP test results have been registered in the Center for Cancer Genomics and Advanced Therapeutics (C-CAT), a nationwide registry database that includes genomic and clinical information, including prognosis and treatment details. Here, leveraging clinicogenomic data from the C-CAT database, we (1) assess the prognostic impact of CGP-reported clinical evidence levels assigned to genetic alterations. Then, we (2) evaluate the proportion of patients who received CGP-guided approved–experimental genomic biomarker-linked therapies and (3) clarify their differences among tumor types. In addition, we (4) investigate the effectiveness of CGP-based tumor-agnostic treatments and reveal their differences among tumor types or alteration profiles. Furthermore, we (5) compare the performance of CGP and non-CGP CDx and examine the response to genomic biomarker-linked therapies when their results are discordant.

Results

Prognostic impact of CGP-guided clinical evidence-level classification

Between June 2019 and June 2024, 54,185 patients with advanced solid tumors receiving CGP using F1CDx were registered in C-CAT, which contained genomic information for all patients and prognostic information for more than 85% (n = 47,380; Extended Data Fig. 1a). This cohort comprised 81 tumor types, including rare tumor types such as extramammary Pagetʼs disease (EMPD) (Extended Data Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 1). The median number of mutations, copy number alterations and rearrangements per patient in each tumor type ranged from 4 to 12, 0 to 8 and 0 to 1, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 1c).

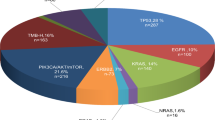

According to the C-CAT evidence-level classification (which closely aligns with Association for Molecular Pathology/American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists (AMP/ASCO/CAP) guidelines) (Extended Data Fig. 2a)24,25, 16.6% of patients had genetic alterations with level A evidence (Fig. 1a), which predicts response to PMDA-approved or FDA-approved therapies. Among them, 11.2% had alterations for which the corresponding therapies were approved in Japan (by the PMDA) at the time of CGP testing (hereafter referred to as level A (approved), otherwise level A (unapproved); Methods). In addition, 8.1%, 47.4%, 0.6% and 17.5% of patients had genetic alterations whose highest evidence level was B (based on well-powered studies), C (approved in another tumor type), D (based on case reports) and E (based on preclinical studies), respectively. Meanwhile, 9.8% of patients had genetic alterations with no evidence.

a, Fraction of patients classified by the highest C-CAT evidence level assigned to genetic alterations. b, Kaplan−Meier survival curves for overall survival in 47,380 patients with survival data available, stratified by the highest C-CAT evidence level. Patients with level A–E alterations are shown. c, Log-transformed hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for overall survival, comparing patients with level A (approved) (left) or level A (unapproved) (right) alterations to those with level C–E alterations, stratified by the number of treatment regimens before CGP. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients with level A (approved) or level A (unapproved) (left) and level C–E (right) alterations, respectively. d, Log-transformed HRs with 95% CI for overall survival, comparing patients with level A (approved) alterations to those with level C–E alterations across 30 tumor types (with ≥10 patients having level A (approved) alterations). Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients with level A (approved) (left) and level C–E (right) alterations, respectively. e, Log-transformed HRs with 95% CI for overall survival, comparing patients with level A (unapproved) alterations to those with level C–E alterations across 19 tumor types (with ≥10 patients having level A (unapproved) alterations). Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients with level A (unapproved) (left) and level C–E (right) alterations, respectively. b–e, P values were derived from two-sided Wald tests in multivariable Cox proportional hazard models, without adjustments for multiple comparisons. c–e, Circles represent HRs, and horizontal lines represent 95% CIs. GI-NET, gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor.

First, we investigated the prognostic impact of CGP-reported clinical evidence levels assigned to genetic alterations (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Albeit with a moderate effect size (hazard ratios = 0.79 and 0.84), patients with level A (approved) and level A (unapproved) alterations had significantly superior outcomes compared to patients with level C–E alterations, which showed almost the same and the worst clinical outcome (Fig. 1b). The median overall survival was 16.4 months, 14.5 months and 12.2 months for level A (approved), level A (unapproved) and level C–E alterations, respectively. Patients with level B alterations also showed slightly better prognosis (hazard ratio = 0.93). Although patients who had received no or one treatment regimen before CGP showed a better prognosis than those with two or more regimens, the impact of level A alterations was similar irrespective of the number of prior regimens (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 2b).

We then investigated the differences in prognostic impact of clinical evidence levels across tumor types. Patients with level A (approved) alterations had significantly better prognosis than patients with level C–E alterations in 10 tumor types, with endometrial and biliary tract cancers and NSCLC being prominent (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Table 1). Conversely, in EMPD, level A (approved) alterations were associated with much worse prognosis (Extended Data Fig. 2c). In colorectal cancer, patients with level A (approved) alterations had slightly worse survival compared to patients with level C–E alterations, consistent with the negative prognostic impact of BRAF mutations (Extended Data Fig. 2d). Moreover, patients with level A (unapproved) alterations had better prognosis than patients with level C–E alterations in three tumor types, namely NSCLC, pancreatic cancer and biliary tract cancer (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 2e). Patients with NSCLC with level B alterations also had better prognosis (Extended Data Fig. 2f). Taken together, these findings demonstrate the clinical usefulness of systematic detection of genetic alterations with clinical evidence levels and administration of related molecularly targeted therapies, although substantial differences exist among tumor types.

Proportion of patients receiving CGP-guided genomic biomarker-linked therapies

We next investigated what proportion of patients benefit from CGP testing by counting patients who received CGP-guided genomic biomarker-linked therapies, namely those who changed treatment strategy and/or content (excluding best supportive care (BSC)) through CGP. Among 15,436 patients with post-CGP treatment strategy information, 12,090 (78.3%) received active treatment after CGP testing, whereas the remaining received BSC (Extended Data Figs. 1a and 3a). Most actively treated patients received insurance-approved treatment, including chemotherapy, molecularly targeted therapy and immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI), whereas 10.2% were enrolled in clinical trials, and 3.1% received off-label drugs, which did not affect prognosis (Extended Data Fig. 3b).

In patients with level A (unapproved) or level B‒D alterations who received active treatment, we estimated the proportion of patients benefitting from CGP testing as the proportion of patients who were enrolled in clinical trials or received off-label drugs that exceeded the proportion (11.4%) observed in patients harboring alterations with level E or no evidence (Fig. 2a). As a result, 5.3%, 4.1%, 3.8% and 7.6% of patients were estimated to receive experimental genomic biomarker-linked therapies. This proportion was negatively affected by older age, poor performance status, double cancers and unavailability of clinical trials for the corresponding biomarker-linked therapy (Extended Data Fig. 3c–f). In patients with level A (approved) alterations who received active treatment and had pre-CGP and post-CGP treatment regimens available (Extended Data Fig. 1a), 24.7% had already received the corresponding genomic biomarker-linked therapy before CGP, and only 62.5% received it for the first time after CGP (Fig. 2b). Combined together, only 8.0% of patients were estimated to receive CGP-guided approved–experimental genomic biomarker-linked therapies (Fig. 2c and Methods), demonstrating a substantial difference from the proportion of patients harboring actionable alterations.

a, Fraction of patients enrolled in clinical trials (red) and receiving off-label drugs (blue) according to the C-CAT evidence level in patients who received active treatment after CGP. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients. The dotted line represents the average fraction of patients harboring alterations with level E or no evidence (11.4%). Double-headed arrows with percentages indicate the increase in the fraction compared to the average fraction of patients harboring alterations with level E or no evidence, which is the proportion of patients who are considered to benefit from CGP. b, Fraction of patients receiving corresponding genomic biomarker-linked therapies before and (or) after CGP in 1,558 patients with level A (approved) alterations and post-CGP treatment regimens available. Patients receiving the corresponding genomic biomarker-linked therapy for the first time after CGP (pink) are considered to benefit from CGP. c, Fraction of patients with clinically actionable alterations (with evidence levels A–D) (left) and patients estimated to benefit from CGP (right) in the entire cohort. d, Fraction of patients estimated to benefit from CGP according to year of CGP testing.

The proportion of patients with level A or B alterations increased over the years, doubling from 9.8% and 5.7% in 2019–2020 to 21.5% and 12.3% in 2023–2024, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 3g), reflecting the recent approval of many genomic biomarker-linked therapies. Consistently, the estimated proportion of patients receiving CGP-guided genomic biomarker-linked therapies steadily increased, nearly doubling from 5.5% in 2019–2020 to 10.0% in 2023–2024 (Fig. 2d).

Differences in the proportion of patients receiving CGP-guided genomic biomarker-linked therapies across tumor types

We next interrogated the details of level A (approved) biomarker-linked therapies. The most common biomarker was TMB-H in all solid tumors, followed by high microsatellite instability (MSI-H) in non-colorectal cancers and BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation/loss in ovarian cancer (Extended Data Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 2). The proportion of CGP-guided administration of genomic biomarker-linked therapies was the highest for NTRK fusion in all solid tumors, followed by BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation/loss in prostate cancer and FGFR2 fusion in biliary tract cancer (Extended Data Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 2), all of which lacked non-CGP CDx for detecting somatic alterations. By contrast, the proportion was low for BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation/loss in ovarian cancer and KIT mutation in gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), reflecting the approval of olaparib and imatinib, regardless of mutation status, respectively26,27. The proportion was relatively low for alterations with non-CGP CDx available, such as ERBB2 amplification, BRAF V600 mutation and ALK and ROS1 fusions. Although non-CGP CDx is approved for MSI-H, the proportion of CGP-guided administration of pembrolizumab was high in non-colorectal cancers.

Among tumor types, the proportion of CGP-guided administration of approved genomic biomarker-linked therapies was relatively low in tumor types for which tumor-type-specific genomic biomarker-linked therapies and their related non-CGP CDx were available, such as esophagogastric adenocarcinoma (EGAC) and breast cancer (Fig. 3a). Similarly, it was limited in tumor types where such therapies have been approved over several years, including imatinib for GIST and ICIs for melanoma, bladder–urinary tract cancer and NSCLC. Conversely, the proportion was virtually 100% in rare tumor types where only CGP-based tumor-agnostic genomic biomarkers were available.

a, Fraction of patients receiving corresponding genomic biomarker-linked therapies before and (or) after CGP in patients with level A (approved) alterations and post-CGP treatment regimens available across 39 tumor types (with ≥100 patients). Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients. Patients receiving the corresponding genomic biomarker-linked therapy for the first time after CGP (pink) are considered to benefit from CGP. b, Difference in the fraction of patients enrolled in clinical trials or receiving off-label drugs between patients with level A (unapproved) or B–D alterations and those with level E or no evidence across 39 tumor types. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients with A (unapproved) or B–D alterations (top) and with level E or no evidence (bottom), respectively. c, Fraction of patients with clinically actionable alterations (with evidence levels A–D) across 39 tumor types. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients. d, Fraction of patients estimated to receive CGP-guided approved–experimental genomic biomarker-linked therapies across 39 tumor types. CNS, central nervous system; GI-NET, gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor; NA, not available; PNS, peripheral nervous system.

The estimated proportion of patients with level A (unapproved) or B–D alterations who received experimental genomic biomarker-linked therapies was high in thyroid cancer and melanoma (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 4b). Several tumor types, including pancreatic cancer and cancer of unknown primary (CUP), showed negative values. This is probably due to the unavailability of genomic biomarker-linked therapies and/or the enrichment of actionable alterations undetectable by F1CDx in patients lacking actionable alterations in these tumor types28. Notably, clinical trial enrollment did not affect prognosis in any tumor types, whereas off-label drug use was associated with worse prognosis in several tumor types (Extended Data Fig. 4c).

As for level A (approved) alterations, GIST had the highest proportion, followed by NSCLC, small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and EGAC (Fig. 3c). By contrast, these alterations were rarely (<5.0%) detected in pancreatic cancer, soft tissue sarcoma and glioma. In addition, several tumor types, including breast and bladder–urinary tract cancers, showed smaller proportions than expected from the literature1,2, partly due to unapproved indications in Japan (Methods). CGP-guided genomic biomarker-linked therapies were rarely administered in multiple tumor types, including pancreatic and liver cancers and GIST (Fig. 3d). Conversely, NSCLC and SCLC had a modest proportion of patients receiving such therapies (>15.0%). Several tumor types, such as thyroid cancer, had a higher proportion, due to frequent administration of experimental genomic biomarker-linked therapies. These results indicate greater inter-tumor type differences in the proportion of patients benefitting from CGP than in the proportion of patients harboring actionable alterations (coefficient of variation, 0.75 versus 0.30; P = 9.0 × 10−6).

Differences in the efficacy of pembrolizumab in TMB-H patients across tumor types

F1CDx covers several tumor-agnostic genomic biomarkers with level A evidence for which non-CGP CDx is not available, including TMB-H and NTRK fusions. Overall, 8.5% of patients were TMB-H (≥10 mutations per megabase (Mb)), most frequently in SCLC, NSCLC and EMPD, accounting for 38.7% of patients with level A (approved) alterations (Extended Data Figs. 4a and 5a). The assessment of best overall response (BOR) showed that, in patients without ICI treatment before CGP (ICI-naive), the objective response rate (ORR) (partial response and complete response) to pembrolizumab was 25.9% (Extended Data Fig. 5b). As most (87.0%) TMB-H patients received pembrolizumab after CGP among ICI-naive patients with post-CGP treatment regimens available, we analyzed the prognosis of TMB-H patients after CGP. As expected, TMB-H patients showed a superior prognosis to TMB-low (TMB-L) patients, almost all of whom received other treatments (Extended Data Fig. 5c).

We then analyzed the differences in the efficacy of pembrolizumab in TMB-H patients among tumor types (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 3). A considerable proportion (8.0‒66.7%) of TMB-H patients showed objective responses in 17 tumor types. By contrast, four tumor types showed no response, including EMPD, with all patients having progressive disease. Inter-tumor type comparison revealed that TMB-H patients showed or tended to show better prognosis than TMB-L patients in many tumor types (Fig. 4b). These included not only tumor types included in clinical trials29 but also others, such as pancreatic cancer (Extended Data Fig. 5d). Notably, in only EMPD, TMB-H patients showed worse outcomes than TMB-L patients (Fig. 4c), compatible with the ORR results. Thus, EMPD is considered an exceptional tumor where pembrolizumab is ineffective against TMB-H, explaining the worse prognosis of patients with level A (approved) alterations.

a, BOR to pembrolizumab in ICI-naive TMB-H patients across 21 tumor types (with ≥3 patients). b, Log-transformed hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for overall survival for ICI-naive TMB-H patients compared to TMB-L patients across 23 tumor types (with ≥10 TMB-H patients). Circles represent HRs, and horizontal lines represent 95% CIs. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of TMB-H (left) and TMB-L (right) patients evaluated, respectively. c, Kaplan−Meier survival curves for overall survival in 72 ICI-naive patients with EMPD stratified by TMB status. d, BOR to pembrolizumab in TMB-H patients without (ICI-naive) and with prior ICI treatment. e, BOR to pembrolizumab in TMB-H patients with prior ICI treatment (including pembrolizumab) across nine tumor types (with ≥3 patients). f, BOR to pembrolizumab in ICI-naive TMB-H patients stratified by MSI status and TMB levels. d,f, ORR was compared using two-sided Fisher’s exact test. a,d−f, Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients. g, Kaplan−Meier survival curves for overall survival in 1,174 ICI-naive TMB-H patients stratified by MSI status and TMB levels. h, Multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression of overall survival incorporating sex, age category, MSI status and TMB levels in 1,174 ICI-naive TMB-H patients. Squares represent HRs, and horizontal lines represent 95% CIs. b,c,g,h, P values were derived from two-sided Wald tests in multivariable Cox proportional hazard models, without adjustments for multiple comparisons. CR, complete response; GI-NET, gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

The C-CAT cohort included TMB-H patients with ICI treatment before CGP who received pembrolizumab after CGP. Notably, ICI-treated patients showed a similar response to pembrolizumab after CGP compared to ICI-naive patients, regardless of tumor type (Fig. 4d,e and Supplementary Table 3), demonstrating the promising efficacy of pembrolizumab rechallenge in TMB-H tumors.

MSI-H substantially overlaps with TMB-H and may more consistently predict better response to ICIs than TMB-H29,30,31,32. Overall, MSI-H was observed in 1.6% of patients and was most common in endometrial cancer (Extended Data Fig. 5a). As reported33,34, most MSI-H patients were TMB-H, whereas MSI-H patients accounted for only 18.2% of TMB-H patients (Extended Data Fig. 6a). Among TMB-H patients, microsatellite stable (MSS) patients exhibited lower TMB than MSI-H patients (Extended Data Fig. 6b).

We first assessed the impact of MSI status or TMB levels on clinical outcomes in ICI-naive TMB-H patients. Within TMB-H patients, the ORR to pembrolizumab was lower in MSS patients than in MSI-H patients (Extended Data Fig. 6c), confirming findings from clinical trials29,30. Similarly, MSS patients had a slightly lower survival than MSI-H patients (Extended Data Fig. 6d). As for TMB levels, patients with TMB of 10‒20 mutations/Mb showed significantly lower ORR than those with TMB of ≥20 mutations/Mb (Extended Data Fig. 6e). Moreover, patients with TMB of 10‒20 mutations/Mb had worse outcomes than patients with TMB of ≥20 mutations/Mb but almost equivalent outcomes to TMB-L patients (Extended Data Fig. 6f). The prognostic impact of TMB levels remained consistent across different tumor types, with TMB of ≥20 mutations/Mb being significantly associated with better prognosis in five of them (Extended Data Fig. 6g,h).

Next, we stratified TMB-H patients by both MSI status and TMB levels. Compared to MSS patients with TMB of 10‒20 mutations/Mb, both MSS and MSI-H patients with TMB of ≥20 mutations/Mb showed better ORR, whereas MSI-H patients with TMB of 10‒20 mutations/Mb had similar ORR (Fig. 4f). Furthermore, compared to MSS patients with TMB of 10‒20 mutations/Mb, TMB of ≥20 mutations/Mb showed better prognosis, whereas MSI-H patients with TMB of 10‒20 mutations/Mb had almost equivalent survival (Fig. 4g). Additionally, multivariate analysis showed that TMB levels were independently associated with prognosis, whereas MSI status was not (Fig. 4h). These results suggest that TMB of ≥20 mutations/Mb can predict better prognosis, irrespective of MSI status.

Differences in the response of TRK inhibitors to various NTRK fusions

NTRK fusions were identified in 109 patients with various tumor types, particularly with salivary gland cancer and soft tissue sarcoma (Extended Data Fig. 7a and Supplementary Table 4). The most common was ETV6−NTRK3 (n = 42), followed by LMNA−NTRK1 (n = 15) and TPM3−NTRK1 (n = 10). ETV6−NTRK3 was more frequent in tumor types where NTRK fusions are relatively common, such as salivary gland cancer and breast cancer (Supplementary Table 4). The ORRs for entrectinib and larotrectinib after CGP were 55.0% and 66.7%, respectively, similar to those in clinical trials35,36. The ORR was significantly higher for ETV6−NTRK3 (88.9%) than for other NTRK fusions (45.0%) (Extended Data Fig. 7b), which was validated through the reanalysis of the previous clinical trials35,36 (Extended Data Fig. 7c). In addition, patients harboring ETV6−NTRK3 had the best prognosis, followed by patients with other NTRK fusions, compared to those without NTRK fusions (Extended Data Fig. 7d). These findings suggest inferior efficacy of TRK inhibitors to NTRK fusions with less frequent partners, which are more common in tumor types rarely having NTRK fusions.

There are several tumor-type-specific genomic biomarkers with level A evidence for which non-CGP CDx was not available, namely BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation/loss in prostate cancer and FGFR2 fusion in biliary tract cancer. The targeted therapies for these alterations yielded a clinically meaningful ORR (Extended Data Fig. 8a). Moreover, patients harboring these alterations had better prognosis than those without (Extended Data Fig. 8b,c).

Effectiveness of genomic biomarker-linked therapies in patients with discordant results between non-CGP CDx and CGP

As non-CGP CDx assays are available for several genetic alterations (Supplementary Table 2), we evaluated the concordance between non-CGP CDx and CGP results. Among patients positive for either or both tests, 80.1% showed concordant positive results, whereas only non-CGP CDx and only CGP were positive for 8.6% and 11.2%, respectively (Fig. 5a). Such discordant results were more common for fusions, MSI and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) IHC/ISH than for mutations (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Fig. 9), consistent with previous reports7,22,23.

a, Concordance rate between non-CGP CDx and CGP among patients positive by either or both tests for each genetic alteration and primary organ/tissue. (+) and (−) indicate positive and negative results, respectively. b, BOR to trastuzumab with or without pertuzumab in combination with hormone therapy and (or) chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer harboring ERBB2 amplification (determined by CGP), stratified by HER2 status determined by IHC/ISH assays. For patients treated with trastuzumab in multiple post-CGP regimens, only the earliest treatment with BOR data available was included. HER2-negative and HER2-low patients had no administration of trastuzumab and/or pertuzumab before CGP, whereas most HER2-positive patients had received these therapies before CGP. c, BOR to EGFR inhibitors in patients with lung cancer harboring EGFR mutations (determined by CGP), stratified by EGFR mutation status determined by non-CGP CDx. For patients treated with multiple EGFR inhibitors, the earliest treatment with BOR data available was included. Patients negative by non-CGP CDx had no administration of EGFR inhibitors before CGP, whereas most positive patients had received these therapies before CGP. a–c, Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients. CR, complete response; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Then, we investigated the efficacy of genomic biomarker-linked therapies in patients with discordant results. Notably, all three patients with NSCLC who were negative for ALK fusions by non-CGP CDx but positive by CGP showed partial response to ALK inhibitors (Table 1). Additionally, another patient with lung cancer who was positive for ROS1 fusions only by CGP had partial response to a ROS1 inhibitor. Three patients with breast cancer and one patient with esophageal–stomach cancer with no or low HER2 expression by non-CGP CDx but positive for ERBB2 amplification by CGP showed partial response or complete response to HER2-targeting antibody−drug conjugates (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 5). Furthermore, patients with breast cancer who were positive for ERBB2 amplification only by CGP showed similar responses to anti-HER2 antibodies to patients who were positive by both tests (Fig. 5b). Similar results were obtained for EGFR inhibitors used for patients with EGFR-mutated lung cancer (mostly NSCLC) (Fig. 5c).

Discussion

Large-scale clinical sequencing projects have demonstrated the value of CGP by showing that many patients harbor actionable alterations (Supplementary Table 6)1,2,8,9. Particularly, the initiatives at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center laid the groundwork as a prospective clinical sequencing platform, clarifying the difference of clinical actionability across major tumor types and its temporal change using the OncoKB knowledge base2,8. The registry databases (for example, AACR Project GENIE) have collected such real-world sequencing data at scale, facilitating the discovery of rare alterations across diverse tumors and the characterization of alterations in rare tumors3,4,37. Moreover, early non-randomized clinical trials, in which the definition and (or) extent of matching were retrospectively determined, showed that patients receiving matched therapies (or CGP-guided genomic biomarker-linked therapies) achieve improved survival15,16,17,18. However, although a positive result was reported in a randomized controlled trial in HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer, others in all solid tumors failed to reproduce these findings19,20,21. Thus, there are differing views on whether CGP and related genomic biomarker-linked therapies improve the overall outcomes with advanced solid tumors. Meanwhile, multiple basket or platform trials (for example, NCI-MATCH) have yielded clinical evidence for the efficacy of biomarker-linked therapies within specific genomically defined subgroups, ultimately supporting tumor-agnostic regulatory approval38,39,40,41.

In this context, the C-CAT database can bridge knowledge gaps not covered by previous studies. Its nationwide coverage reflects real-world practice, and its large sample size and detailed clinical information enable assessment of the efficacy of genomic biomarker-linked therapies in contexts where evidence is limited, including rare tumor types (for example, ICIs for EMPD), rare alterations (for example, NTRK fusions) and discordant results between non-CGP CDx and CGP. More notably, utilizing prospective annotation for genetic alterations, we demonstrate that CGP-guided clinical evidence-level classification enables prognostic stratification in advanced solid tumors irrespective of the timing of CGP. Particularly, level A and B alterations can predict better outcomes, which are more prominent in NSCLC and pancreatobiliary cancers. Therefore, CGP-guided administration of approved–experimental genomic biomarker-linked therapies (potentially excluding off-label drug use) can more consistently improve outcomes, although several alterations themselves affect prognosis. Leveraging adequate information on treatment details before and after CGP, we estimate that only 8.0% of patients benefit from CGP at present, despite clinically actionable alterations (with evidence levels A–D) being identified in 72.7%. The large gap between the two proportions was compatible with prospective cohort studies from selected institutions8,14,17. Notably, our pan-cancer analysis identifies a substantial inter-tumor type difference in the proportion of patients benefitting from CGP testing. These findings provide more reliable estimates of where CGP provides the most clinical benefit.

Although the phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study contributed to the tumor-agnostic approval of pembrolizumab for patients harboring a TMB of ≥10 mutations/Mb, this treatment was not effective across all tumor types, indicating limitations of a single TMB threshold29,42. Indeed, several small-scale pan-cancer analyses showed that TMB of ≥20 mutations/Mb better predicts ICI responses43,44. Additionally, a retrospective study of 22 patients with advanced MSI-H colorectal cancer showed that increasing TMB levels can further stratify outcomes after ICIs among MSI-H patients45. Here we found that TMB of ≥20 mutations/Mb can predict better prognosis not only in MSS patients but also in MSI-H patients in a pan-cancer manner. These observations suggest the potential complementarity of CGP-based TMB measurement and MSI testing in this setting.

Although several studies, including KEYNOTE-158, investigated the efficacy of ICIs in TMB-H patients across multiple tumor types29,30,43,46,47, evidence was limited in rare tumor types and in those where TMB-H is infrequent. Our large-scale analysis enables a more comprehensive assessment of diverse tumor types, demonstrating the effectiveness of ICIs for TMB-H patients in pancreatic cancer (containing only 2.0% of TMB-H patients), consistent with other reports48. More importantly, patients with EMPD showing TMB-H are exceptionally resistant to pembrolizumab, unlike patients with other tumor types. EMPD is a rare, slow-growing skin cancer that is characterized by the immunologically cold tumor microenvironment enriched with regulatory T cells49,50, which may confer ICI resistance51,52. Although clinical practice guidelines recommend considering ICI for patients with metastatic EMPD with TMB-H53, physicians should be cautious.

Although non-CGP CDx and CGP are complementary in cancer precision medicine, a clinically challenging and evidence-scarce situation is when their results are discordant. Our study shows that several patients with genomic biomarkers negative by non-CGP CDx but positive by CGP respond to corresponding biomarker-linked therapies. Therefore, such therapies are worth administering even in patients with discordant results.

This study has several limitations, including the lack of detailed information of clinical trials and off-label drug use, limited availability of post-CGP treatment regimens and the absence of an independent central review for treatment response. Nevertheless, we provide a comprehensive evaluation of the real-world clinical utility of CGP and its differences across tumor types and molecular contexts, offering valuable insights into its role in guiding treatment decisions in cancer precision medicine. These findings further underscore the importance of clinicogenomic registry databases in advancing precision oncology and optimizing therapeutic strategies for improved patient outcomes.

Methods

C-CAT dataset preparation

Since June 2019, data from almost all CGP under Japan’s national health insurance system have been collected to C-CAT, with written informed consent from each patient. Patients did not receive any compensation for data registration. In principle, each patient receives a single CGP test over his/her lifetime because of the limitation of reimbursement in Japan54. C-CAT registration date was used as the date of CGP testing. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at the National Cancer Center (approval number: 2021-249). The secondary use of the C-CAT data for academic research purposes was approved by the C-CAT data utilization review board (C-CAT proposal control number: CDU2022-003). Information on patient background (including sex, age, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) and presence of another cancer), somatic alterations (mutations, copy number alterations and rearrangements) with clinical evidence level, drug approval status and clinical trial availability in Japan, treatment details (before and after CGP) and prognosis (v.20240621) was downloaded from the C-CAT portal (https://research-use.c-cat.ncc.go.jp/).

All 54,185 patients receiving CGP using F1CDx were included in this study, of whom 47,380 (87.4%) had survival data. Among them, there were 27,844 females, 26,336 males and five patients with missing sex information, based on self-reporting. Age at CGP ranged from 0 to 99 years (capped at 99), with a median age of 63 years. A total of 1,153 patients were younger than 20 years, and 2,087 were aged 80 years or older.

Tumor types were annotated based on the OncoTree code55 and were categorized into main types, with minor modifications (Supplementary Table 1). In particular, hepatobiliary cancer was divided into liver cancer and biliary tract cancer; esophagogastric cancer was divided into EGAC and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC); and EMPD was distinguished from skin cancer (other). Among the 81 tumor types identified in the C-CAT cohort, 39 with 100 or more patients were included for tumor-type-specific analyses while excluding patients whose subclassification details were not available.

Evaluation of clinically actionable alterations

The clinical evidence level of each genetic alteration was annotated according to the C-CAT evidence-level classification at the time of CGP testing, which closely aligns with AMP/ASCO/CAP guidelines (Extended Data Fig. 2a)24,25. Although the C-CAT evidence-level classification includes evidence levels A–F and R1–R3 (resistance related), evidence levels A−E were evaluated in this study. Evidence level A was further classified into level A (approved) and level A (unapproved), depending on whether corresponding genomic biomarker-linked therapies were approved in Japan at the time of CGP testing. These unapproved indications included PIK3CA amplification in breast cancer (targeted by alpelisib and capivasertib), FGFR3 fusion in bladder–urinary tract cancer (targeted by erdafitinib), IDH1 mutation in biliary tract cancer (targeted by ivosidenib) and mutation/loss of genes involved in homologous recombination (other than BRCA1/BRCA2) in prostate cancer (targeted by olaparib and talazoparib). Patients were classified by genetic alterations with the highest evidence level.

Evaluation of pre-CGP treatment regimens

Among 54,185 patients evaluated, information on pre-CGP treatment regimens was available for 49,184 (90.8%) patients, of whom 43,747 had survival data (Extended Data Fig. 1a). The details of treatment regimens were obtained from the C-CAT portal and manually reviewed. The number of treatment regimens before CGP was counted unless they were used in the perioperative period. For prognostic analysis of each biomarker, patients without administration of the corresponding genomic biomarker-linked therapy before CGP were evaluated, unless otherwise specified.

Evaluation of post-CGP treatment strategy

The post-CGP treatment strategy included clinical trials, off-label drug use, insurance-approved treatments and BSC, which were prioritized in this order. Treatment strategies other than BSC were categorized as active treatment. For patients with missing information, post-CGP treatment strategy was estimated from other treatment information if possible. In total, 15,436 patients (28.5% of total) had post-CGP treatment strategy information available, of whom 15,201 had survival data (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Specific details of clinical trials and off-label treatments were not available for most patients.

Evaluation of post-CGP treatment regimens and their responses

Among 12,090 patients receiving active treatment after CGP, information on post-CGP treatment regimens was available for 7,057 (58.4%) (Extended Data Fig. 1a). The details of treatment regimens were obtained from the C-CAT portal and manually reviewed. BOR to post-CGP treatment was reported by the treating physicians at each institution according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors v.1.1 (ref. 56), as recommended by the C-CAT data submission manual. For each biomarker, patients with BOR data available for the corresponding genomic biomarker-linked therapies were evaluated.

Evaluation of approved genomic biomarker-linked therapy administration rate

Patients with level A (approved) alterations and post-CGP treatment regimens available were classified based on the presence (+) or absence (−) of administration of genomic biomarker-linked therapy before and after CGP testing. For patients with multiple evidence A (approved) alterations, we prioritized in the following order: (−) and (+), (+) and (+), (+) and (−) and (−) and (−) before and after CGP.

Estimating the proportion of patients receiving CGP-guided genomic biomarker-linked therapies

The proportion of patients receiving CGP-guided genomic biomarker-linked therapies was calculated as the sum of the proportions of (1) patients with level A (approved) alterations who received approved genomic biomarker-linked therapy for the first time after CGP testing and (2) patients with level A (unapproved) or B–D alterations who received experimental genomic biomarker-linked therapies. The proportion (1) was calculated as the proportion of patients with level A (approved) alterations in all patients (6,043 / 54,185 = 11.2%) × the proportion of patients receiving active treatment after CGP in those with level A (approved) alterations whose pre-CGP treatment regimens and post-CGP treatment strategy were available (2,066 / 2,355 = 87.7%) × the proportion of patients who received corresponding genomic biomarker-linked therapy for the first time after CGP in those with level A (approved) alterations who received active treatment after CGP and whose information on both pre-CGP and post-CGP treatment regimens was available (974 / 1,558 = 62.5%). The proportion (2) for patients with level A (unapproved) alterations was calculated as the proportion of patients with level A (unapproved) alterations in all patients (2,951 / 54,185 = 5.4%) × the proportion of patients receiving active treatment after CGP in those with level A (unapproved) alterations whose pre-CGP treatment regimens and post-CGP treatment strategy were available (906 / 1,090 = 83.1%) × the increase in the proportion of patients who were enrolled in clinical trials or received off-label drugs in patients with level A (unapproved) alterations compared to patients harboring alterations with level E or no evidence (151 / 906 – 292 / 2,563 = 5.3%), with negative values treated as zero. This calculation was also conducted independently for patients with level B–D alterations, and the total proportion (2) was calculated as the sum across all levels. The same analysis was performed according to tumor type and year of CGP testing. The coefficients of variation for the proportion of patients benefitting from CGP and those harboring actionable alterations among tumor types were compared using modified signed likelihood ratio test in the R package cvequality (v.0.2.0).

Survival analysis

Overall survival was defined as the time from the date of CGP to the date of death or last follow-up. Survival analyses were performed using the R package survival (v.3.5-5). Multivariable analyses were performed using the Kaplan−Meier method with Cox proportional hazard model, adjusted for sex and age category (<65 years, 65–74 years and ≥75 years), unless otherwise specified. P values from multivariable Cox proportional hazard models were calculated using two-sided Wald test.

TMB-H

Patients with a TMB of ≥10 mutations/Mb who were assigned with level A evidence were defined as TMB-H, and patients with a TMB of <10 mutations/Mb were defined as TMB-L. In total, 3,930 patients were excluded from this analysis mainly due to undetermined TMB by CGP. TMB levels of TMB-H patients were classified into TMB of 10‒20 mutations/Mb and TMB of ≥20 mutations/Mb. MSI status was also evaluated by CGP using F1CDx and classified into MSI-H and MSS, after excluding an additional 3,627 patients with equivocal or undetermined MSI status. Response to pembrolizumab and prognosis were assessed in all tumor types and in each tumor type, where patients were stratified by a history of ICI treatment. In addition, the effects of TMB levels and (or) MSI status on response to pembrolizumab and prognosis were evaluated.

NTRK fusions

NTRK fusions (with level A evidence) were identified in 109 patients, and their tumor type and fusion partner were analyzed. In addition, response to TRK inhibitors and prognosis were assessed and compared between patients harboring ETV6−NTRK3 and those harboring other NTRK fusions. The same comparison was performed for 48 patients for entrectinib35 and for 54 patients for larotrectinib36 using published clinical trials. The objective tumor response for target lesions was estimated from the waterfall plots of the maximum change in tumor size.

Tumor-type-specific genomic biomarkers with level A evidence

Response to targeted therapies and prognosis were assessed for tumor-type-specific genomic biomarkers with level A evidence for which non-CGP CDx was not available. BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation/loss in prostate cancer was included, as non-CGP CDx detects only germline variants.

Concordance of CGP testing results and non-CGP CDx

The results of all non-CGP CDx for level A (approved) biomarkers, together with KRAS and NRAS mutations in bowel cancer, were reported by the treating physicians at each institution (Supplementary Table 2). Biomarkers with at least 10 positive patients by non-CGP CDx in each primary organ/tissue were evaluated for concordance between CGP and non-CGP CDx, excluding CDx assays that evaluate only germline BRCA1/BRCA2 variants. Specifically, information on (1) KRAS and NRAS G12, G13, A59, Q61, K117 and A146 mutations in bowel cancer, (2) BRAF V600 mutation in bowel and skin cancers, (3) EGFR exon 19 deletion, exon 20 insertion and G719, S768I, T790M, L858R and L861Q mutations in lung cancer, (4) ALK and ROS1 fusions in lung cancer and (5) HER2 expression and (or) amplification (by IHC and/or ISH) in breast, head–neck, esophagus–stomach and bowel cancers was evaluated. For breast, esophagus/stomach and bowel cancers, HER2-positive expression was defined as IHC 3+ or IHC 2+ with gene amplification by ISH; HER2-low expression was defined as IHC 1+ or IHC 2+ without gene amplification; and HER2-negative expression was defined as IHC 0+. For head–neck cancer, HER2 status was evaluated only by IHC. Patients who tested negative by non-CGP CDx but received corresponding genomic biomarker-linked therapies before CGP were excluded from the analysis due to potential misreporting.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed with R 4.1.1 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) in RStudio, primarily using the R packages tidyverse (v.1.3.2), dplyr (v.1.0.10), readxl (v.1.4.0) and stringi (v.1.7.12) for data manipulation and ggplot2 (v.3.5.1), cowplot (v.1.1.1) and ggsurvfit (v.0.2.0) for visualization. Comparison of categorical data was performed using two-sided Fisher’s exact test.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from C-CAT (https://www.ncc.go.jp/en/c_cat/about) under controlled access due to ethical and privacy restrictions. The application process for data access is described on the C-CAT website under ‘Steps from application to data utilization’ (https://www.ncc.go.jp/en/c_cat/use/flow/index.html) and consists of the following steps: (1) a principal investigator submits the C-CAT data use application form with a research protocol and a copy of the approval from their research ethics committee and the head of their institution to C-CAT (c-cat_use@ml.res.ncc.go.jp), which is expected to respond within approximately 1 week; (2) the application is reviewed by the C-CAT data utilization review board; (3) once approved, an ‘Agreement on Utilization of C-CAT Data’ is concluded between National Cancer Center Japan (governing C-CAT) and the institution of the principal investigator; (4) after the agreement is signed and the access fee is paid (with academic institutions generally exempt), the access license to the ‘C-CAT Research-Use Portal site’ is granted; and (5) upon obtaining access, registered data licensees can connect to the portal using their registered computers over Transport Layer Security (TLS). The granted access is valid for 1 year, after which renewal of both the agreement and the access license is required. The data available to registered data licensees include: (1) deidentified data from individual patients, including patient background, treatment details (before and after CGP) and clinical outcomes, and (2) somatic alteration calls with clinical evidence levels, drug approval status and clinical trial availability in Japan. C-CAT prohibits data licensees from offering, selling or reselling relevant data to any third parties.

At present, principal investigators are restricted to individuals affiliated with hospitals for cancer genomic medicine, industries and research institutes in Japan. Therefore, researchers outside Japan may access the C-CAT data by collaborating with investigators based in Japan. In such cases, the same procedure, including the approval from the C-CAT data utilization review board, is required. Although the timeframe is yet to be determined, direct data access is expected to become available to researchers/applicants outside Japan in the near future. The ‘Number-of-Records Search site’ (https://simplesearch-use.c-cat.ncc.go.jp/en/), which provides the number of the registered records of interest in the C-CAT cohort, is publicly available.

Code availability

The custom code used in this study is available at https://github.com/nccmo/C-CAT_actionability_2025.

References

Chakravarty, D. & Solit, D. B. Clinical cancer genomic profiling. Nat. Rev. Genet. 22, 483–501 (2021).

Suehnholz, S. P. et al. Quantifying the expanding landscape of clinical actionability for patients with cancer. Cancer Discov. 14, 49–65 (2024).

Horie, S. et al. Pan-cancer comparative and integrative analyses of driver alterations using Japanese and international genomic databases. Cancer Discov. 14, 786–803 (2024).

Pugh, T. J. et al. AACR Project GENIE: 100,000 cases and beyond. Cancer Discov. 12, 2044–2057 (2022).

Tsimberidou, A. M. et al. Molecular tumour boards—current and future considerations for precision oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20, 843–863 (2023).

Lu, C. C. et al. Tumor-agnostic approvals: insights and practical considerations. Clin. Cancer Res. 30, 480–488 (2024).

Milbury, C. A. et al. Clinical and analytical validation of FoundationOne®CDx, a comprehensive genomic profiling assay for solid tumors. PLoS ONE 17, e0264138 (2022).

Zehir, A. et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat. Med. 23, 703–713 (2017).

Park, K. H. et al. Genomic landscape and clinical utility in Korean advanced pan-cancer patients from prospective clinical sequencing: K-MASTER program. Cancer Discov. 12, 938–948 (2022).

Chakravarty, D. et al. Somatic genomic testing in patients with metastatic or advanced cancer: ASCO provisional clinical opinion. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 1231–1258 (2022).

Mosele, M. F. et al. Recommendations for the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for patients with advanced cancer in 2024: a report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann. Oncol. 35, 588–606 (2024).

Presley, C. J. et al. Association of broad-based genomic sequencing with survival among patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer in the community oncology setting. JAMA 320, 469–477 (2018).

Paz-Ares, L. et al. Genomic testing among patients with newly diagnosed advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the United States: a contemporary clinical practice patterns study. Lung Cancer 167, 41–48 (2022).

Trédan, O. et al. Molecular screening program to select molecular-based recommended therapies for metastatic cancer patients: analysis from the ProfiLER trial. Ann. Oncol. 30, 757–765 (2019).

Massard, C. et al. High-throughput genomics and clinical outcome in hard-to-treat advanced cancers: results of the MOSCATO 01 trial. Cancer Discov. 7, 586–595 (2017).

Tsimberidou, A. M. et al. Long-term overall survival and prognostic score predicting survival: the IMPACT study in precision medicine. J. Hematol. Oncol. 12, 145 (2019).

Belcaid, L. et al. Copenhagen Prospective Personalized Oncology (CoPPO)—impact of comprehensive genomic profiling in more than 2000 patients in a phase I setting. Ann. Oncol. 36, 1078−1087 (2025).

Sicklick, J. K. et al. Molecular profiling of cancer patients enables personalized combination therapy: the I-PREDICT study. Nat. Med. 25, 744–750 (2019).

Andre, F. et al. Genomics to select treatment for patients with metastatic breast cancer. Nature 610, 343–348 (2022).

Le Tourneau, C. et al. Molecularly targeted therapy based on tumour molecular profiling versus conventional therapy for advanced cancer (SHIVA): a multicentre, open-label, proof-of-concept, randomised, controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 16, 1324–1334 (2015).

Tsimberidou, A. M. et al. 638P Final results of IMPACT 2, a randomized study evaluating molecular profiling and targeted agents in metastatic cancer at MD Anderson Cancer Center. Ann. Oncol. 35, S506–S507 (2024).

Lin, D. I. et al. Pan-tumor validation of a NGS fraction-based MSI analysis as a predictor of response to pembrolizumab. npj Precis. Oncol. 8, 204 (2024).

Mack, P. C. et al. Real-world clinical performance of a DNA-based comprehensive genomic profiling assay for detecting targetable fusions in nonsquamous NSCLC. Oncologist 29, e984–e996 (2024).

Kohno, T. et al. C-CAT: the national datacenter for cancer genomic medicine in Japan. Cancer Discov. 12, 2509–2515 (2022).

Li, M. M. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of sequence variants in cancer: a joint consensus recommendation of the Association for Molecular Pathology, American Society of Clinical Oncology, and College of American Pathologists. J. Mol. Diagn. 19, 4–23 (2017).

Ledermann, J. et al. Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 1382–1392 (2012).

Demetri, G. D. et al. Efficacy and safety of imatinib mesylate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 472–480 (2002).

Philip, P. A. et al. Molecular characterization of KRASwild-type tumors in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 28, 2704–2714 (2022).

Marabelle, A. et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol. 21, 1353–1365 (2020).

Marcus, L. et al. FDA approval summary: pembrolizumab for the treatment of tumor mutational burden–high solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 27, 4685–4689 (2021).

Marabelle, A. et al. Efficacy of pembrolizumab in patients with noncolorectal high microsatellite instability/mismatch repair–deficient cancer: results from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 1–10 (2020).

Sha, D. et al. Tumor mutational burden as a predictive biomarker in solid tumors. Cancer Discov. 10, 1808–1825 (2020).

Chalmers, Z. R. et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med. 9, 34 (2017).

Goodman, A. M., Sokol, E. S., Frampton, G. M., Lippman, S. M. & Kurzrock, R. Microsatellite-stable tumors with high mutational burden benefit from immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Res. 7, 1570–1573 (2019).

Doebele, R. C. et al. Entrectinib in patients with advanced or metastatic NTRK fusion-positive solid tumours: integrated analysis of three phase 1-2 trials. Lancet Oncol. 21, 271–282 (2020).

Drilon, A. et al. Efficacy of larotrectinib in TRKfusion−positive cancers in adults and children. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 731–739 (2018).

AACR Project GENIE Consortium. AACR Project GENIE: powering precision medicine through an international consortium. Cancer Discov. 7, 818–831 (2017).

Flaherty, K. T. et al. Molecular landscape and actionable alterations in a genomically guided cancer clinical trial: National Cancer Institute Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice (NCI-MATCH). J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 3883–3894 (2020).

Salama, A. K. S. et al. Dabrafenib and trametinib in patients with tumors with BRAFV600E mutations: results of the NCI-MATCH Trial Subprotocol H. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 3895–3904 (2020).

Mangat, P. K., Kirkwood, M. K., Hinshaw, D. C., Garrett-Mayer, E. & Schilsky, R. L. Prevalence of targetable genomic alterations among a diverse population participating in the ASCO TAPUR Study. npj Precis. Oncol. 9, 222 (2025).

Hainsworth, J. D. et al. Targeted therapy for advanced solid tumors on the basis of molecular profiles: results from MyPathway, an open-label, phase IIa multiple basket study. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 536–542 (2018).

Wang, X. et al. Tumor mutational burden for the prediction of PD-(L)1 blockade efficacy in cancer: challenges and opportunities. Ann. Oncol. 35, 508–522 (2024).

Goodman, A. M. et al. Tumor mutational burden as an independent predictor of response to immunotherapy in diverse cancers. Mol. Cancer Ther. 16, 2598–2608 (2017).

Palmeri, M. et al. Real-world application of tumor mutational burden-high (TMB-high) and microsatellite instability (MSI) confirms their utility as immunotherapy biomarkers. ESMO Open 7, 100336 (2022).

Schrock, A. B. et al. Tumor mutational burden is predictive of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in MSI-high metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 30, 1096–1103 (2019).

Samstein, R. M. et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat. Genet. 51, 202–206 (2019).

Duvivier, H. L. et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with tumors with high tumor mutational burden: results from the Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 5140–5150 (2023).

Quintanilha, J. C. F. et al. Tumor mutational burden in real-world patients with pancreatic cancer: genomic alterations and predictive value for immune checkpoint inhibitor effectiveness. JCO Precis. Oncol. 7, e2300092 (2023).

Press, J. Z. et al. FOXP3+ regulatory T-cells are abundant in vulvar Paget’s disease and are associated with recurrence. Gynecol. Oncol. 120, 296–299 (2011).

Fujimura, T. et al. Possible mechanisms of the crosstalk between Langerhans cells and regulatory T cells in extramammary Paget disease by receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B (RANK) ligand/RANK pathways. Br. J. Dermatol. 176, 387–394 (2017).

Kumagai, S. et al. The PD-1 expression balance between effector and regulatory T cells predicts the clinical efficacy of PD-1 blockade therapies. Nat. Immunol. 21, 1346–1358 (2020).

van Gulijk, M. et al. PD-L1 checkpoint blockade promotes regulatory T cell activity that underlies therapy resistance. Sci. Immunol. 8, eabn6173 (2023).

Kibbi, N. et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for extramammary Paget disease. JAMA Oncol. 8, 618–628 (2022).

Naito, Y. et al. Clinical practice guidance for next-generation sequencing in cancer diagnosis and treatment (edition 2.1). Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 233–283 (2021).

Kundra, R. et al. OncoTree: a cancer classification system for precision oncology. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 5, 221–230 (2021).

Eisenhauer, E. A. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (v.1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 45, 228–247 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (JP22K20808 and JP25K18889, to Y.S.); the Kobayashi Foundation for Cancer Research (to Y.S.); the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (Project for Promotion of Cancer Research and Therapeutic Evolution (JP22ama221510 and JP25ama221543), to K.K., and Core Research for Evolutionary medical Science and Technology (JP25gm1810002h0004), to K.K.); the Japan Science and Technology Agency Moonshot R&D Program (JPMJMS2022, to K.K.); the Takeda Science Foundation (to Y.S.); and the Uehara Memorial Foundation (to K.K.). The results published here are based upon data generated by C-CAT (https://www.ncc.go.jp/en/c_cat/about).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S.: conceptualization, resources, data curation, software, formal analysis, funding acquisition, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing. S.H.: resources, data curation, investigation and writing—review and editing. Y.K.: investigation and writing—review and editing. K.M.: investigation and writing—review and editing. Y.I.: investigation and writing—review and editing. Y.M.: investigation and writing—review and editing. H.K.: investigation and writing—review and editing. Z.T.: investigation and writing—review and editing. J.K.: investigation and writing—review and editing. T.F.: investigation and writing—review and editing. K.H.: investigation and writing—review and editing. K.K.: conceptualization, formal analysis, supervision, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft, project administration and writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Y.K. receives honoraria from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, outside the submitted work. T.F. receives clinical trial drugs free of charge from Chugai Pharmaceutical and MSD K.K., outside the submitted work. K.H. receives grants from MSD K.K., outside the submitted work. K. Kataoka receives grants and personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Chugai Pharmaceutical, outside the submitted work. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Stephen J. Chanock, Mark Rubin and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available. Primary Handling Editor: Anna Maria Ranzoni, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Overview of the C-CAT cohort.

a, Flow chart of patient selection (left) and corresponding subsets for overall (center; Figs. 1–3 and Extended Data Figs. 1–4) and individual biomarker analyses (right; Figs. 4 and 5, Table 1 and Extended Data Figs. 5–9). b, Distribution of tumor types among 54,185 patients in the C-CAT cohort. The inner and outer circles indicate primary organs/tissues and tumor types, respectively. Tumor types with ≥100 patients per primary organ/tissue and available subclassification details are visualized. More details are shown in Supplementary Table 1. c, Distribution of the number of mutations (log-transformed; top), copy number alterations (middle) and rearrangements (bottom) per patient in each tumor type. Black bars indicate the median.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Classification of clinical evidence levels and their prognostic impact in individual tumor types.

a, Classification of C-CAT evidence levels (A–E) and their corresponding evidence levels in the AMP/ASCO/CAP guidelines25. The Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are the regulatory agencies of Japan and the United States, respectively. b, KaplanMeier survival curves for overall survival in 43,747 patients with pre-CGP treatment regimen and survival data available, stratified by the number of treatment regimens before CGP. P value was derived from a two-sided Wald test in a multivariable Cox proportional hazard model. c–e, KaplanMeier survival curves for overall survival in patients with EMPD (c), colorectal cancer (d), NSCLC (e, left), pancreatic cancer (e, middle) and biliary tract cancer (e, right), stratified by the highest C-CAT evidence level. Evidence levels with ≥10 patients are shown. f, Log-transformed hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for overall survival, comparing patients with level B alterations to those with level C–E alterations across 22 tumor types (with ≥10 patients having level B alterations). Circles represent HRs, and horizontal lines represent 95% CIs. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients with level B (left) and level C–E (right) alterations, respectively. P values were derived from two-sided Wald tests in multivariable Cox proportional hazard models, without adjustments for multiple comparisons.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Factors influencing the proportion of patients receiving CGP-guided genomic biomarker-linked therapies.

a, Fraction of patients receiving active treatment according to the C-CAT evidence level in patients with pre-CGP treatment regimen and post-CGP treatment strategy information available. b, KaplanMeier survival curves for overall survival in 15,201 patients with survival data and pre-CGP treatment regimen and post-CGP treatment strategy information available, stratified by post-CGP treatment strategies. P values were derived from two-sided Wald tests in multivariable Cox proportional hazard models, without adjustments for multiple comparisons. c–f, Fraction of patients enrolled in clinical trials (red) and receiving off-label drugs (blue) in patients who received active treatment after CGP and whose highest level was A (unapproved) or B–D. Patients were stratified by age at CGP (c), ECOG PS (d), presence of double cancer (e) and clinical trial availability in Japan at the time of CGP (f). The dotted line represents the average fraction of patients harboring alterations with level E or no evidence (11.4%). Two-sided Fisher’s exact test. g, Fraction of patients with clinically actionable alterations (with evidence levels A–D) according to year of CGP testing. Two-sided Cochran–Armitage trend test. a,c–g, Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Details of level A (approved) biomarker-linked therapies.

a, Number of patients with each level A (approved) alteration in the entire cohort (left). Fraction of patients receiving corresponding genomic biomarker-linked therapies before and/or after CGP in patients with each level A (approved) alteration who received active treatment after CGP and whose post-CGP treatment regimens were available (right). Alterations with ≥10 patients (based on the right panel) are shown. Mismatch repair (MMR) genes include MSH2, MSH6, MLH1 and PMS2. EGFR amplification (NSCLC) is currently not classified as level A. See Supplementary Table 2 for details. b, Fraction of patients enrolled in clinical trials (red) and receiving off-label drugs (blue) in patients who received active treatment after CGP across 39 tumor types (with ≥100 patients). a,b, Numbers in parentheses indicate the evaluated patients. c, Log-transformed hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for overall survival, comparing patients enrolled in clinical trials (top) or receiving off-label drugs (bottom) to those receiving insurance-approved treatment across 21 tumor types (with ≥10 patients enrolled in clinical trials (top) or receiving off-label drugs (bottom)). Circles represent HRs, and horizontal lines represent 95% CIs. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients enrolled in clinical trials (top) or receiving off-label drugs (bottom) (left), and those receiving insurance-approved treatment (right). P values were derived from two-sided Wald tests in multivariable Cox proportional hazard models, without adjustments for multiple comparisons.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Clinical and genetic features of TMB-H patients across tumor types.

a, Fraction of TMB-H and/or MSI-H patients among 40 tumor types (with ≥50 patients and subclassification detail available). Patients in which CGP was performed after TMB-H had been classified as level A were evaluated. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients. b, BOR to pembrolizumab in 320 ICI-naive TMB-H patients in all tumor types. c, KaplanMeier survival curves for overall survival in 32,935 ICI-naive patients stratified by TMB status in all tumor types. d, KaplanMeier survival curves for overall survival in 4,459 ICI-naive patients with pancreatic cancer, stratified by TMB status. c,d, P values were derived from two-sided Wald tests in multivariable Cox proportional hazard models.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Relationships between TMB-H and MSI-H patients.

a, Venn diagram showing the overlap between TMB-H and MSI-H patients in the entire cohort. Patients in which CGP was performed after TMB-H had been classified as level A were evaluated. b, Fraction of patients with TMB of 10‒20 mutations/Mb and ≥20 mutations/Mb stratified by MSI status. c, BOR to pembrolizumab in ICI-naive TMB-H patients, stratified by MSI status. d, KaplanMeier survival curves for overall survival in 1,174 ICI-naive TMB-H patients, stratified by MSI status. e, BOR to pembrolizumab in ICI-naive patients with TMB of 10‒20 mutations/Mb and those with TMB of ≥20 mutations/Mb. b,c,e, Two-sided Fisher’s exact test; ORR was compared in c and e. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients. f, KaplanMeier survival curves for overall survival in 32,935 ICI-naive patients stratified by TMB levels. g, Log-transformed hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for overall survival for ICI-naive patients with TMB of ≥20 mutations/Mb compared to TMB-L patients across 12 tumor types (with ≥10 patients having TMB of ≥20 mutations/Mb). Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients with TMB of ≥20 mutations/Mb (left) and TMB-L patients (right), respectively. h, Log-transformed HRs with 95% CI for overall survival for ICI-naive patients with TMB of 10‒20 mutations/Mb compared to TMB-L patients across 18 tumor types (with ≥10 patients having TMB of 10‒20 mutations/Mb). Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients with TMB of 10‒20 mutations/Mb (left) and TMB-L patients (right), respectively. d,f,g,h, P values were derived from two-sided Wald tests in multivariable Cox proportional hazard models, without adjustments for multiple comparisons. g,h, Circles represent HRs, and horizontal lines represent 95% CIs.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Response to TRK inhibitors and prognostic impact of NTRK fusions.

a, Distribution of tumor types in patients with NTRK fusions. Further details are provided in Supplementary Table 4. b, BOR to entrectinib or larotrectinib in patients with ETV6–NTRK3 fusions and in those with other NTRK fusions in the C-CAT cohort. c, Objective tumor response to entrectinib or larotrectinib for target lesions in patients with ETV6–NTRK3 fusions and in those with other NTRK fusions using published clinical trials of entrectinib35 and larotrectinib36. b,c, ORR was compared using two-sided Fisher’s exact test. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients. d, KaplanMeier survival curves for overall survival in patients with ETV6–NTRK3 fusions, those with other NTRK fusions and those without NTRK fusions in tumor types with at least one NTRK fusion-harboring patient. P values were derived from two-sided Wald tests in multivariable Cox proportional hazard models, without adjustments for multiple comparisons.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Response and prognostic impact of tumor-type-specific genomic biomarkers with level A evidence.

a, BOR to PARP inhibitor (olaparib) in patients with BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation/loss in prostate cancer and FGFR inhibitors (futibatinib or pemigatinib) in patients with FGFR2 fusion in biliary tract cancer. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients. b, KaplanMeier survival curves for overall survival in patients with and without BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation/loss in prostate cancer. c, KaplanMeier survival curves for overall survival in patients with and without FGFR2 fusion in biliary tract cancer. b,c, P values were derived from two-sided Wald tests in multivariable Cox proportional hazard models.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Concordance between non-CGP CDx (IHC/ISH) and CGP in patients with ERBB2 amplification.

Fraction of patients with ERBB2 amplification (determined by CGP) in breast cancer (a), bowel cancer (b) and esophagus/stomach cancer (c), stratified by HER2 status determined by IHC/ISH assays. Two-sided Fisher’s exact test. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of evaluated patients.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Table 1: Sample numbers, alterations and treatments by tumor type. Supplementary Table 2: Details of level A (approved) alterations. Supplementary Table 3: Number of TMB-H patients and responses to pembrolizumab by tumor type. Supplementary Table 4: Number of NTRK fusion-harboring patients and responses to TRK inhibitors by tumor type. Supplementary Table 5: Responses to anti-HER2 antibodies or HER2-targeting antibody−drug conjugates after CGP in patients with breast cancer who were negative by non-CGP CDx but positive by CGP for ERBB2 amplification. Supplementary Table 6: Summary of clinical trials, large-scale clinical sequencing projects and registry databases in precision oncology.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saito, Y., Horie, S., Kogure, Y. et al. Real-world clinical utility of comprehensive genomic profiling in advanced solid tumors. Nat Med (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04086-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04086-8