Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) is the greatest cause of infectious disease deaths worldwide. In highly affected countries, effective TB control requires prompt identification and treatment of individuals with active disease. We examined the performance of TB case-finding in low- and middle-income countries based on a comprehensive analysis of TB diagnosis data reported to the World Health Organization. Using these data we estimated the total number of individuals correctly and incorrectly diagnosed with TB, for 111 countries with a collective 6.8 million TB notifications in 2023. Here we estimate that in 2023, 2.05 (1.83–2.27) million individuals were incorrectly diagnosed with TB (false-positives), and 1.00 (0.71–1.36) million received a false-negative diagnosis, at an assumed 25% disease prevalence among individuals evaluated for TB. As many as three of every ten TB notifications may not have TB, and many individuals with TB receive false-negative diagnoses. Compared to current diagnostic performance, scaling-up new polymerase chain reaction-based diagnostics would substantially reduce under-diagnosis but only produce a small reduction in false-positive diagnoses. Major improvements in TB diagnosis will likely require higher-sensitivity bacteriological tests combined with reduced reliance on clinical diagnosis.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data used in this study were drawn from publicly available datasets (downloadable from https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/data, ‘Case notifications’ and ‘WHO TB burden estimates’ files), as well as published studies listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Code availability

Analytic code used to implement the analysis is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16414104 (ref. 58).

References

World Health Organization. The End TB Strategy (World Health Organization, 2015); https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/the-end-tb-strategy

Steingart, K. R. et al. Fluorescence versus conventional sputum smear microscopy for tuberculosis: a systematic review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 6, 570–581 (2006).

Cattamanchi, A. et al. Sensitivity of direct versus concentrated sputum smear microscopy in HIV-infected patients suspected of having pulmonary tuberculosis. BMC Infect. Dis. 9, 53 (2009).

World Health Organization. Global TB Report 2024 (World Health Organization, 2024); https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024

Sossen, B. et al. The natural history of untreated pulmonary tuberculosis in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 11, 367–379 (2023).

WHO Global TB Programme. WHO Global TB Database 2023 (World Health Organization, accessed 30 March 2025); http://www.who.int/tb/country/data/download/en/

Houben, R. M. G. J. et al. What if they don’t have tuberculosis? The consequences and trade-offs involved in false-positive diagnoses of tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 68, 150–156 (2018).

Walusimbi, S. et al. Meta-analysis to compare the accuracy of GeneXpert, MODS and the WHO 2007 algorithm for diagnosis of smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis. BMC Infect. Dis. 13, 507 (2013).

World Health Organization. National Surveys of Costs Faced by Tuberculosis Patients and Their Households 2015–2021 (World Health Organization, 2022); https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240065536

Laurence, Y. V., Griffiths, U. K. & Vassall, A. Costs to health services and the patient of treating tuberculosis: a systematic literature review. PharmacoEconomics 33, 939–955 (2015).

Tostmann, A. et al. Antituberculosis drug-induced hepatotoxicity: concise up-to-date review. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 23, 192–202 (2008).

Munro, S. A. et al. Patient adherence to tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Med. 4, e238 (2007).

Moreira, J. et al. Weighing harm in therapeutic decisions of smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis. Med. Decis. Making 29, 380–390 (2009).

Horne, D. J. et al. Xpert MTB/RIF and Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra for pulmonary tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 6, CD009593 (2019).

Zifodya, J. S. et al. Xpert Ultra versus Xpert MTB/RIF for pulmonary tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in adults with presumptive pulmonary tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2, CD009593 (2021).

Subbaraman, R. et al. The tuberculosis cascade of care in India’s public sector: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 13, e1002149 (2016).

Naidoo, P. et al. The South African tuberculosis care cascade: estimated losses and methodological challenges. J. Infect. Dis. 216, S702–S713 (2017).

Emani, S. et al. Quantifying gaps in the tuberculosis care cascade in Brazil: a mathematical model study using national program data. PLoS Med. 21, e1004361 (2024).

Lalli, M. et al. Investigating the impact of TB case-detection strategies and the consequences of false positive diagnosis through mathematical modelling. BMC Infect. Dis. 18, 340 (2018).

Cilloni, L., Kranzer, K., Stagg, H. R. & Arinaminpathy, N. Trade-offs between cost and accuracy in active case finding for tuberculosis: a dynamic modelling analysis. PLoS Med. 17, e1003456 (2020).

Chadha, V. K. & Praseeja, P. Active tuberculosis case finding in India – the way forward. Indian J. Tuberc. 66, 170–177 (2019).

Dowdy, D. W., Steingart, K. R. & Pai, M. Serological testing versus other strategies for diagnosis of active tuberculosis in India: a cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS Med. 8, e1001074 (2011).

Steingart, K. R. et al. Commercial serological tests for the diagnosis of active pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 8, e1001062 (2011).

Shewade, H. D., Satyanarayana, S. & Kumar, A. M. Does active case finding for tuberculosis generate more false-positives compared to passive case finding in India? Indian J. Tuberc. 68, 396–399 (2021).

Basinga, P., Moreira, J., Bisoffi, Z., Bisig, B. & Van den Ende, J. Why are clinicians reluctant to treat smear-negative tuberculosis? An inquiry about treatment thresholds in Rwanda. Med. Decis. Making 27, 53–60 (2007).

Vassall, A. et al. Rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis with the Xpert MTB/RIF assay in high burden countries: a cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS Med. 8, e1001120 (2011).

Menzies, N. A., Cohen, T., Lin, H. H., Murray, M. & Salomon, J. A. Population health impact and cost-effectiveness of tuberculosis diagnosis with Xpert MTB/RIF: a dynamic simulation and economic evaluation. PLoS Med. 9, e1001347 (2012).

Portnoy, A. et al. Costs incurred by people receiving tuberculosis treatment in low-income and middle-income countries: a meta-regression analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 11, e1640–e1647 (2023).

Burman, W. et al. Research on the treatment of rifampin-susceptible tuberculosis—time for a new approach. PLoS Med. 21, e1004438 (2024).

Jayasooriya, S. et al. Patients with presumed tuberculosis in sub-Saharan Africa that are not diagnosed with tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 78, 50–60 (2023).

Thompson, R. R. et al. High mortality rates among individuals misdiagnosed with tuberculosis: a matched retrospective cohort study of individuals diagnosed with tuberculosis in Brazil. J. Infect. Dis. 231, 1267–1270 (2025).

Theron, G. et al. Do high rates of empirical treatment undermine the potential effect of new diagnostic tests for tuberculosis in high-burden settings? Lancet Infect. Dis. 14, 527–532 (2014).

Kim, S. et al. Factors associated with tuberculosis treatment initiation among bacteriologically negative individuals evaluated for tuberculosis: an individual patient data meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 22, e1004502 (2025).

Keeler, E. et al. Reducing the global burden of tuberculosis: the contribution of improved diagnostics. Nature 444, 49–57 (2006).

da Silva, M. P. et al. More than a decade of GeneXpert® Mycobacterium tuberculosis/Rifampicin (Ultra) testing in South Africa: laboratory insights from twenty-three million tests. Diagnostics 13, 3253 (2023).

McDowell, A. & Pai, M. Treatment as diagnosis and diagnosis as treatment: empirical management of presumptive tuberculosis in India. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 20, 536–543 (2016).

Mesfin, M. M., Tasew, T. W. & Richard, M. J. The quality of tuberculosis diagnosis in districts of Tigray region of northern Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 19, 13 (2005).

Theron, G. et al. Feasibility, accuracy, and clinical effect of point-of-care Xpert MTB/RIF testing for tuberculosis in primary-care settings in Africa: a multicentre, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 383, 424–435 (2014).

Hanson, C., Osberg, M., Brown, J., Durham, G. & Chin, D. P. Finding the missing patients with tuberculosis: lessons learned from patient-pathway analyses in 5 countries. J. Infect. Dis. 216(Suppl. 7), S686–S695 (2017).

World Health Organization. WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis. Module 3: Diagnosis–Rapid Diagnostics for Tuberculosis Detection (World Health Organization, 2024); https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240089488

Nsawotebba, A. et al. Impact of randomized blinded rechecking program on the performance of the AFB Microscopy Laboratory Network in Uganda: a decadal retrospective study. BMC Infect. Dis. 23, 494 (2023).

Otero, L. et al. Quality assessment of smear microscopy by stratified lot sampling of treatment follow-up slides. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 15, 211–216 (2011).

Mekonen, A. et al. Factors which contributed for low quality sputum smears for the detection of acid fast bacilli (AFB) at selected health centers in Ethiopia: a quality control perspective. PLoS ONE 13, e0198947 (2018).

Desalegn, D. M. et al. Misdiagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis and associated factors in peripheral laboratories: a retrospective study, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 11, 291 (2018).

Murongazvombo, A. S. et al. Where, when, and how many tuberculosis patients are lost from presumption until treatment initiation? A step by step assessment in a rural district in Zimbabwe. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 78, 113–120 (2019).

Chihota, V. N. et al. Missed opportunities for TB investigation in primary care clinics in South Africa: experience from the XTEND trial. PLoS ONE 10, e0138149 (2015).

Dorfman, D. D. & Alf, E. Jr Maximum-likelihood estimation of parameters of signal-detection theory and determination of confidence intervals—rating-method data. J. Math. Psychol. 6, 487–496 (1969).

Abebe, G. et al. Evaluation of the 2007 WHO guideline to diagnose smear negative tuberculosis in an urban hospital in Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis. 13, 427 (2013).

Alamo, S. T. et al. Performance of the new WHO diagnostic algorithm for smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV prevalent settings: a multisite study in Uganda. Trop. Med. Int. Health 17, 884–895 (2012).

Huerga, H. et al. Performance of the 2007 WHO algorithm to diagnose smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in a HIV prevalent setting. PLoS ONE 7, e51336 (2012).

Koole, O. et al. Evaluation of the 2007 WHO guideline to improve the diagnosis of tuberculosis in ambulatory HIV-positive adults. PLoS ONE 6, e18502 (2011).

Siddiqi, K., Walley, J., Khan, M. A., Shah, K. & Safdar, N. Clinical guidelines to diagnose smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in Pakistan, a country with low-HIV prevalence. Trop. Med. Int. Health 11, 323–331 (2006).

Soto, A. et al. Validation of a clinical–radiographic score to assess the probability of pulmonary tuberculosis in suspect patients with negative sputum smears. PLoS ONE 6, e18486 (2011).

Swai, H. F., Mugusi, F. M. & Mbwambo, J. K. Sputum smear negative pulmonary tuberculosis: sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic algorithm. BMC Res. Notes 4, 475 (2011).

Wilson, D. et al. Evaluation of the World Health Organization algorithm for the diagnosis of HIV-associated sputum smear-negative tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 15, 919–924 (2011).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2010).

Rstan: the R interface to Stan. R package 2.21.8 ed (Stan Development Team, 2023).

Menzies, N. Analysis code and data inputs for ‘The potential number of false-positive and false-negative TB diagnoses in low- and middle-income countries: a Bayesian analysis of routine reporting data’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16414104 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (award no. U01AI152084 to N.A.M.). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. We thank N. Arinaminpathy for feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.v.L.T., P.J.D., T.C. and N.A.M. conceptualized the research. A.v.L.T., T.C. and N.A.M. developed the methodology used, and P.J.D., N.A.M. and T.C. validated the methodology. The research was supervised by N.A.M., and coordinated by N.A.M. A.v.L.T. curated data, performed the formal analysis, did the investigation and administered the project. A.v.L.T. and N.A.M. made the visualizations. N.A.M. undertook funding acquisition, and resources were provided by N.A.M. The original draft was written by A.v.L.T. and N.A.M., and reviewed, edited and approved by all authors. A.v.L.T. and N.A.M. have full access to all data in the study. All authors read and approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Katharina Kranzer and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Lia Parkin, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

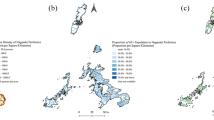

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

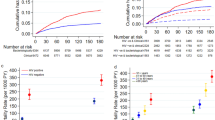

Extended Data Fig. 1 Estimates of the probability of false-positive diagnosis and false-negative diagnosis for different values of initial TB prevalence and the percentage of notifications that are laboratory confirmed, for the three alternative specifications.

Panel A: Probability of false-positive diagnosis under an alternative analytic specification assuming an optimistic ROC curve for clinical diagnosis (see Supplementary Fig. 2). Panel B: Probability of false-negative diagnosis under an alternative analytic specification assuming an optimistic ROC curve for clinical diagnosis (see Supplementary Fig. 2). Panel C: Probability of false-positive diagnosis under an alternative analytic specification assuming a pessimistic ROC curve for clinical diagnosis (see Supplementary Fig. 2). Panel D: Probability of false-negative diagnosis under an alternative analytic specification assuming a pessimistic ROC curve for clinical diagnosis (see Supplementary Fig. 2). Panel E: Probability of false-positive diagnosis under an alternative analytic specification assuming that 25% of individuals evaluated for TB are only evaluated clinically. Panel F: Probability of false-negative diagnosis under an alternative analytic specification assuming that 25% of individuals evaluated for TB are only evaluated clinically. Probability of false-positive diagnosis defined as the probability that someone diagnosed with TB does not have TB (1 – PPV). Probability of false-negative diagnosis defined as the probability that someone diagnosed as not having TB does have TB (1 – NPV). Colors indicate different probability levels, indicated by values shown in each panel. All inputs apart from the sensitivity and specificity of clinical diagnosis held at their global average values. Sensitivity and specificity of clinical diagnosis calculated as a function of other values, based on the ROC curve shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. ‘+’ symbol in center of each plot represents mean values from the main analysis.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Schematic of TB diagnosis model.

Figure presents a flow diagram showing how individuals can progress through the diagnostic algorithm. Boxes represent steps in the algorithm. ‘+’ symbols indicate a positive result on an individual step of the algorithm, ‘–‘ symbols indicate a negative result on an individual step of the algorithm. Red lines indicate individuals with TB, blue lines indicate individuals without TB. Dashed lines represent a mechanism explored in sensitivity analysis, but not in the main analysis.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–3 and Figs. 1 and 2.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

van Lieshout Titan, A., Dodd, P.J., Cohen, T. et al. Estimating the number of incorrect tuberculosis diagnoses in low- and middle-income countries. Nat Med (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04097-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04097-5