Abstract

STEER (NCT05089656) was a 52-week, phase 3, multicenter, randomized, sham-controlled, double-blind trial evaluating intrathecal onasemnogene abeparvovec (OAV101 IT), a one-time gene transfer therapy, in patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). Participants ranged in age from 2 years to <18 years, were treatment-naive and were able to sit but never walked independently. Primary efficacy endpoint was change from baseline in Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale-Expanded (HFMSE) score. In total, 126 patients received OAV101 IT (n = 75) or a sham procedure (n = 51). The primary endpoint was met: patients treated with OAV101 IT demonstrated a significant increase in HFMSE score compared with sham (least squares mean difference, 1.88 (95% confidence interval: 0.51−3.25); P = 0.0074). Overall incidence of adverse events (AEs), serious adverse events (SAEs) and adverse events of special interest (AESI) was similar between groups. Transaminase increases were infrequent; most were low grade and transient. Two participants in the OAV101 IT arm and one participant in the sham arm developed sensory symptoms. One-time OAV101 IT demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in motor function compared with sham control. The overall safety findings were acceptable, with similar incidences of AEs, SAEs and AESI in the OAV101 IT and sham groups. Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05089656.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

SMA is a rare genetic neuromuscular disease that occurs as a result of biallelic deletion or variants of the SMN1(survival motor neuron 1) gene, leading to reduced levels of functional survival motor neuron (SMN) protein, subsequent irreversible loss of motor neurons and progressive muscle weakness that affects breathing, swallowing and movement. Although SMA manifests across a wide range of phenotypes, infantile-onset forms are especially debilitating and progressive, requiring treatment to prevent further loss of motor neurons and functional deterioration1,2,3,4.

SMA was historically classified into four subgroups (types 1−4) based on the age of symptom onset and the highest motor function achieved, with an additional subgroup (type 0) to describe antenatal-onset cases1,2. However, this classification, based on the natural history of SMA, does not account for the effects of disease-modifying treatments on SMA phenotypes. Advances in therapy, including two SMN2 splicing modifiers, nusinersen (periodic IT administration)5, risdiplam (daily oral therapy)6 and onasemnogene abeparvovec gene transfer therapy (single intravenous administration)7, have reshaped the clinical landscape. As a result, the current consensus recognizes SMA as a phenotypic continuum, and patients are now categorized into functional groups—non-sitters, sitters and walkers—based on their current motor abilities rather than their historical disease progression8.

Newborn genetic screening and early treatment have improved the clinical course of SMA dramatically9. Nusinersen and risdiplam are two currently available treatments, but both require lifelong administration, either through intermittent IT injections or daily oral dosing, respectively. Challenges associated with chronic administration include the burden of repeated administration and potential non-compliance. Onasemnogene abeparvovec as a single intravenous administration is limited to patients younger than 2 years of age in the United States or to those weighing less than 21 kg in European countries7,10. As such, there remains a need for a safe and effective, one-time gene therapy option that provides sustained expression of SMN protein. To address this unmet need, OAV101 IT offers a fixed dose that reduces systemic viral vector exposure, making it a potential one-time treatment for a broad range of patients with SMA regardless of age and weight. In a completed phase 1/2 dose-ranging trial (STRONG; NCT03381729), OAV101 IT was demonstrated to be safe and well tolerated in patients with SMA aged 6 months to <60 months11. None of these patients experienced any events suggestive of the non-progressive histopathologic findings in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) previously reported in non-human primates (NHPs)12,13,14,15. The phase 3 STEER trial (NCT05089656) evaluated OAV101 IT for patients with SMA 2 years to <18 years of age who were treatment-naive and sitting but never walked independently. Selection of the OAV101 IT dose (1.2 × 1014 vector genomes) for STEER was based on the totality of data from STRONG (the same dose used in cohort B)11 and non-clinical studies12.

Results

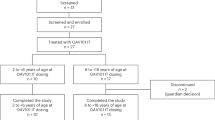

Participant disposition

Participants were enrolled at 29 sites in 14 countries. A total of 217 participants were screened for enrollment; four did not complete the screening phase and 77 failed screening based on inclusion/exclusion criteria, with the main reasons being Cobb angle greater than 40°, hepatic dysfunction and anti-adeno-associated virus serotype 9 (AAV9) antibody titer > 1:50 (Fig. 1). In total, 126 participants were treated with OAV101 IT (n = 75) or the sham procedure (n = 51), and 122 participants (OAV101 IT, n = 72; sham, n = 50) completed the 52-week Period 1. Two participants in the OAV101 IT group discontinued during Period 1 (guardian decision, n = 1; physician decision, n = 1). In the sham group, one participant discontinued due to SAEs during Period 1. At the time of data cutoff, one participant was counted as ongoing due to an exploratory respiratory inductance plethysmography assessment that was conducted after their week 52 visit. The first participant first visit was 1 February 2022, and the last participant last visit (week 52 visit) was 12 November 2024.

Baseline demographics and characteristics

As presented in Table 1, treatment groups were balanced in terms of demographics and baseline characteristics. Mean (s.d.) age at dosing was 5.89 (3.58; range, 2.1–16.6) years for the OAV101 IT group and 5.87 (3.05; range, 2.4–14.2) years for the sham group. Most participants had three SMN2 gene copies (OAV101 IT, 97.3%; sham, 90.2%). Mean (s.d.) HFMSE scores at baseline were 17.97 (10.11; range, 1.0–41.0) in the OAV101 IT group and 18.17 (9.76; range, 2.0–42.5) in the sham group (Table 1). In the 2 to <5 years age subgroup, 42 participants received OAV101 IT and 29 received the sham procedure. In the 5 to <18 years age subgroup, 33 participants were treated with OAV101 IT and 22 received the sham procedure.

Primary efficacy endpoint

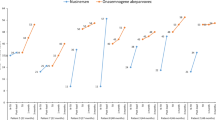

At the end of Follow-Up Period 1, the study met its primary efficacy endpoint, demonstrating a 2.39-point improvement in HFMSE score for the OAV101 IT group versus 0.51 points for the sham group (least squares mean (LSM) difference, 1.88 (95% confidence interval: 0.51−3.25); P = 0.0074) (Figs. 2 and 3). The primary endpoint was assessed using the initial α level of 0.01, as no α carryover occurred from the secondary endpoints in the 2 to <5 years age subgroup. This greater improvement in HFMSE score for the OAV101 IT group was noted as early as week 4 and maintained throughout Follow-Up Period 1.

The primary efficacy endpoint was analyzed using a mixed model with repeated measurements, with the observed change from baseline in HFMSE score at all post-baseline visits (through the end of Follow-Up Period 1) as the dependent variable. The fixed effects included treatment, visit, treatment by visit interaction and the strata and baseline HFMSE score as covariates. An unstructured covariance matrix was used. LSM for each treatment group, standard errors, difference of LSM compared with the sham procedure group as well as the two-sided P values were determined by visit and treatment. OAV101 IT, n = 74; sham, n = 50. Note: End of Follow-Up Period 1 was defined as the average of the week 48 and week 52 assessments.

Change from baseline in HFMSE and RULM scores was analyzed using a mixed model with repeated measurements, with the observed change from baseline in HFMSE/RULM score at all post-baseline visits (through the end of Follow-Up Period 1) as the dependent variable. The fixed effects included treatment, visit, treatment by visit interaction and the strata and baseline HFMSE/RULM score as covariates. An unstructured covariance matrix was used. LSM for each treatment group, standard errors, associated 95% CIs, difference of LSM compared to the sham procedure group and the associated 95% CIs for the difference, as well as the two-sided P values, were determined by visit and treatment. The dichotomous endpoint (percentage of responders, defined as participants who achieved at least a 3-point improvement from baseline in HFMSE score at the end of Follow-Up Period 1) was analyzed by logistic regression model with Firth correction, including treatment, strata and baseline HFMSE score as covariates. OAV101 IT, n = 74; sham, n = 50. Note: Group estimates are displayed as LSM (s.e.m.) for change from baseline endpoints and as n/m (%) for achievement of at least a 3-point improvement in HFMSE score (n = number of patients achieving at least a 3-point improvement from baseline in HFMSE score; m = total number of patients at the end of Follow-Up Period 1). Treatment effect is displayed as LSM (95% CI) for change from baseline endpoints and as log(OR) (95% CI) for achievement of at least a 3-point improvement in HFMSE score. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Secondary efficacy endpoints

The secondary endpoints did not achieve statistical significance according to the prespecified multiple testing strategy (described in detail in the supplementary methods). Nominal P values are reported here. In the overall population, a numerically greater percentage of participants in the OAV101 IT group achieved a ≥3-point increase in HFMSE score compared with the sham group at the end of Follow-Up Period 1 (39.2% versus 26.0%; odds ratio: 2.03 (95% confidence interval: 0.90−4.57); P = 0.0879) (Fig. 3). In the overall age group, the LSM change from baseline to the end of Follow-Up Period 1 in Revised Upper Limb Module (RULM) score was 2.44 versus 0.92 for the OAV101 IT versus sham group, respectively (LSM difference, 1.52 (95% confidence interval: 0.34−2.71); P = 0.0122) (Fig. 3). The LSM change from baseline in RULM score indicated a numerically greater score for the OAV101 IT group compared with the sham group as early as week 4, continuing through the end of Follow-Up Period 1 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

In the 2 to <5 years age subgroup, LSM change from baseline in HFMSE score was 3.00 versus 1.56 for OAV101 IT versus sham, with an LSM difference of 1.44 (95% confidence interval: –0.33 to 3.22; P = 0.1097) (Fig. 4a). A numerically greater percentage of participants in this subgroup achieved a ≥3-point increase in HFMSE score in the OAV101 IT group compared with the sham group (48.8% versus 37.9%, respectively; odds ratio: 1.27 (95% confidence interval: 0.46−3.56), P = 0.6448). Lastly, in the 2 to <5 years age subgroup, LSM change from baseline in RULM score at the end of Follow-Up Period 1 was 3.27 versus 1.82 for OAV101 IT versus sham, with an LSM difference of 1.45 (95% confidence interval: –0.22 to 3.12; P = 0.0873) (Fig. 4a).

Change from baseline in HFMSE and RULM scores was analyzed using a mixed model with repeated measurements, with the observed change from baseline in HFMSE/RULM score at all post-baseline visits (through the end of Follow-Up Period 1) as the dependent variable. The fixed effects included treatment, visit, treatment by visit interaction and the strata and baseline HFMSE/RULM score as covariates. An unstructured covariance matrix was used. LSM for each treatment group, standard errors, associated 95% CIs, difference of LSM compared with the sham procedure group and the associated 95% CIs for the difference, as well as the two-sided P values, were determined by visit and treatment. a, In the 2 to <5 years age subgroup, the dichotomous endpoint was analyzed using a generalized linear mixed-effects model, including treatment, visit, treatment by visit interaction, strata and baseline HFMSE score as covariates. The model included logistics as the link function, and a compound symmetry matrix was used. b, In the 5 to <18 years age subgroup, the dichotomous endpoint was analyzed using logistic regression model with Firth correction, including treatment, strata and baseline HFMSE score as covariates. OAV101 IT, n = 41; sham, n = 29. OAV101 IT, n = 33; sham, n = 21. Note: Group estimates are displayed as LSM (s.e.m.) for change from baseline endpoints and as n/m(%) for achievement of at least a 3-point improvement in HFMSE score (n = number of patients achieving at least a 3-point improvement from baseline in HFMSE score; m = the total number of patients at the end of Follow-Up Period 1). Treatment effect is displayed as LSM (95% CI) for change from baseline endpoints and as log(OR) (95% CI) for achievement of at least a 3-point improvement in HFMSE score. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Safety

The overall incidence of AEs (OAV101 IT, 97.3%; sham, 90.2%), SAEs (OAV101 IT, 28.0%; sham, 33.3%) and AESI (OAV101 IT, 16.0%; sham, 13.7%) was similar between the two groups (Table 2). The most frequent AEs (>10% for either group) are displayed in Table 2 by preferred term. The most frequent AEs reported for both groups were upper respiratory tract infection, a known comorbidity with SMA, and transient pyrexia. The most frequent SAEs were pneumonia (12.0% versus 13.7%) and vomiting (4.0% versus 0%) in the OAV101 IT group and pneumonia (12.0% versus 13.7%) and lower respiratory tract infection (2.7% versus 7.8%) in the sham group (Supplementary Table 1).

One participant in each group experienced an AE that led to discontinuation from the study. One participant from the sham group discontinued due to an SAE of pneumonia aspiration, and one participant in the OAV101 IT group completed Period 1 but did not meet eligibility criteria for Period 2 and was, therefore, discontinued from the study. This participant experienced signs and symptoms that may be suggestive of DRG toxicity in Period 1 and had an abnormal sensory examination, which is an exclusion criterion for enrollment in Period 2 (Table 2). Within 72 hours after the study treatment administration, the incidence of vomiting, a known complication of lumbar puncture and potential AE of onasemnogene abeparvovec, was greater in the OAV101 IT group compared with the sham group (14.7% versus 2.0%, respectively). The incidences of other known complications associated with lumbar puncture demonstrated a difference of less than 5% between the OAV101 IT and sham groups: nausea (6.7% versus 2.0%), procedural pain (0% versus 2.0%), back pain (2.7% versus 0%) and headache (6.7% versus 2.0%) (Supplementary Table 2).

AESI reported in the study included hepatotoxicity, signs or symptoms that may be suggestive of DRG toxicity (identified via an extensive list of Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 27.1 preferred terms encompassing sensory, motor, and neuropathic abnormalities and other features possibly indicative of dorsal root ganglionopathy irrespective of Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) grade) and transient thrombocytopenia (Table 2). No AESI of malignancies, thrombotic microangiopathy or cardiac AEs were reported for either group.

Events under the hepatotoxicity AESI category were reported in seven participants (9.3%) in the OAV101 IT group versus five participants (9.8%) in the sham group (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3). All events resolved in both groups, except for one participant in the sham group who remained ineligible to receive treatment in Period 2.

Laboratory data indicated that most transaminase increases were <3× the upper limit of normal (ULN) and transient (Supplementary Fig. 2). Increases in transaminases (alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) >2× ULN) were slightly more frequent in the OAV101 IT group compared with the sham group (17.3% versus 9.8%, respectively). ALT increased to >3× ULN in four participants (5.3%) in the OAV101 IT group and in three participants (5.9%) in the sham group. ALT elevations >20× ULN were reported in two participants (2.7%) in the OAV101 IT group. In one participant, the ALT increase began 313 days after dosing, resolved without treatment and normalized in 13 days. In the second participant, ALT elevation started at week 4, peaked at week 7 and normalized by week 12 after prolonged prednisolone administration. One other participant in the OAV101 IT group, who had ALT > 10× ULN, received prolonged prednisolone treatment and intravenous pulse methylprednisolone. No other participant required prolonged prednisolone treatment. No participants (0%) in the sham group had ALT elevations >8× ULN. No participants had increases in total bilirubin >1.5× ULN, and none met the criteria for Hy’s law (Supplementary Table 4).

Transient thrombocytopenia events were reported for four participants (5.3%) in the OAV101 IT group and for two participants (3.9%) in the sham group (Supplementary Table 5). Thrombocytopenia was reported in two participants (2.7%) in the OAV101 IT group versus none in the sham group. All AESI were mild or moderate in intensity, none was severe, none was an SAE and all resolved. Due to the broad search criteria for this AESI, the remaining identified events were minor bleeding events independent of the presence of thrombocytopenia.

Laboratory data indicated a small, transient decrease in mean platelet count (mean change from baseline, −53.3 × 109 per liter) in the OAV101 IT group at week 1, which returned to baseline levels by week 2. Mean platelet values remained relatively unchanged in the sham group throughout the study.

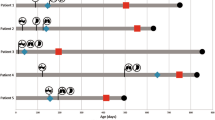

Signs and symptoms that may be suggestive of DRG toxicity were reported for two participants (2.7%) in the OAV101 IT group and for one participant (2.0%) in the sham group (Supplementary Table 6). The two participants in the OAV101 IT group presented with sensory symptoms, and nerve conduction studies revealed decreasing sensory nerve action potential (SNAP) amplitudes with relative preservation of conduction velocities in distributions consistent with sensory symptoms. One OAV101 IT-treated participant was a 16-year-old girl who reported ‘numbness in both legs’ (hypoesthesia) 20 days post-dose, evolving to paresthesia in the feet and associated discomfort and new paresthesia in the bilateral hands approximately 3.5 months post-dose. Throughout the course of symptoms, multiple treatments were administered, including gabapentin, tricyclic antidepressants (nortriptyline and amitriptyline), pregabalin, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), methylprednisolone and rituximab. The effect of treatment on the course of symptoms remained unclear, although symptomatic improvement was reported over the course of follow-up. Stabilization of symptoms in the feet and resolution of symptoms in the hands were reported approximately 6 months post-dose. At week 52, this participant discontinued the study as she was ineligible for Treatment Period 2 because clinically significant abnormal sensory examination was an exclusion criterion. The SAE of ‘hypoesthesia’ was downgraded to an AE at the week 52 visit. The other participant in the OAV101 IT group was a 16-year-old girl who reported ‘tingling sensation over both feet’ (paresthesia) 17 days post-dose. Throughout the course of symptoms, multiple treatments were administered, including intravenous methylprednisolone, gabapentin, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and IVIG. Symptomatic improvement was reported over the course of follow-up. Symptoms initially worsened until approximately week 20 post-dose, followed by gradual improvement beginning at approximately week 34 and then stabilization by week 52. The participant then entered Treatment Period 2 as the abnormal sensory neurologic examination was not clinically significant.

The participant in the sham group was a 7.9-year-old child who reported ‘paresthesia (enveloping sensation of the left thigh spreading all over the body)’ 154 days after the sham procedure. Symptoms were mild, lasted 15 days and resolved without treatment.

Exploratory efficacy endpoints

In the 5 to <18 years age subgroup, LSM change from baseline in HFMSE score was 1.60 versus −0.86 for OAV101 IT versus sham, with an LSM difference of 2.45 (95% confidence interval: 0.42−4.49) (Fig. 4b). In this subgroup, LSM change from baseline in RULM score was 1.42 versus −0.31 in the OAV101 IT versus sham group, with an LSM difference of 1.72 (95% confidence interval: 0.14−3.30) (Fig. 4b).

Discussion

STEER is, to our knowledge, the first randomized, controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of OAV101 IT treatment for patients with SMA across a broad age range (2.1–16.6 years) and baseline motor function (HFMSE scores of 1–41). The study met its primary efficacy endpoint, demonstrating an LSM difference of 1.88 points in HFMSE score between the OAV101 IT and sham control groups. The results for all secondary endpoints demonstrated improvement consistently in favor of OAV101 IT, although statistical significance was not met according to the prespecified multiple testing strategy. The overall safety findings were acceptable, with similar incidences of AEs, SAEs and AESI in the OAV101 IT and sham groups, providing evidence indicating a favorable benefit−risk profile.

In the overall study population (2 to <18 years age group), a statistically significant improvement in motor function was observed for participants receiving OAV101 IT compared with sham procedure. In both the 2 to <5 years and 5 to <18 years age subgroups, the percentage of participants who achieved a ≥3-point increase in HFMSE score was greater in the OAV101 IT group compared with the sham group. The 3-point threshold for the HFMSE responder analysis was selected, indicating improvement in at least two items4, and was used as an endpoint previously in clinical trial studies of later-onset SMA16. Similarly, a greater percentage of participants in the OAV101 IT group achieved a clinically meaningful increase of ≥1.5 points (a minimum clinically important difference established by Coratti et al.17) in their HFMSE score compared to the sham group (supplementary results and Supplementary Fig. 3). Together with the mean change from baseline in HFMSE scores, these responder analyses further support the clinical meaningfulness of the observed treatment effects.

OAV101 IT treatment was also associated with improved upper limb function and fine motor skills, assessed using the RULM. Similar to the HFMSE, a treatment difference was observed for RULM scores as early as week 4, and the change from baseline remained numerically greater for the OAV101 IT group compared with sham. The LSM treatment difference for RULM at 52 weeks was 1.52 points (95% confidence interval: 0.34−2.71; P = 0.0122), supporting the therapeutic benefit of OAV101 IT.

Patient and caregiver surveys indicated awareness of the expected progression of SMA, fear of progressive loss of function and that patients and caregivers considered even minor improvement or stabilization to be important18,19,20. Pera et al.18 found that 75% of caregivers considered that a partial achievement of at least two items (2-point increase in HFMSE) would be considered a benefit and justify participation in a clinical trial. In a study primarily of patients with SMA types 2 or 3, McGraw et al.19 reported that any improvement in motor function was beneficial. For these participants, including 21 patients with SMA, 64 parents and 11 clinicians, meaningful change was relative to functional ability, and small changes or maintenance were viewed as meaningful outcomes19. Rouault et al.20 reported the importance of stabilization to patients with SMA, with 96.5% of respondents indicating that a drug that stabilized their clinical state would represent therapeutic progress with 81.3% considering it major progress.

Clinical investigations of disease-modifying treatments (including pivotal studies of both risdiplam and nusinersen) have demonstrated reduction of treatment effect size for patients with increasing age16,21. Thus, STEER was designed to characterize motor function changes in two age subgroups: 2 to <5 years of age as secondary endpoints and 5 to <18 years of age as exploratory endpoints. In both age subgroups, there was a positive trend consistently favoring the OAV101 IT group compared with sham. In the 5 to <18 years age subgroup, the sham group declined in both HFMSE and RULM, resulting in a treatment difference of 2.45 in HFMSE and 1.72 in RULM. This is in contrast to the experience of the sham group in the 2 to <5 years age subgroup in which the sham group improved by 1.56 in HFMSE and by 1.82 in RULM, resulting in a treatment difference of 1.44 in HFMSE and of 1.45 in RULM. The increases in motor function testing scores in the sham group for the 2 to <5 years age subgroup were consistent with natural history studies in that age range for untreated individuals with SMA due to developmental maturity22. As such, the treatment difference in the 5 to <18 years age subgroup is more than the 2 to <5 years age subgroup. Indeed, the change from baseline for the 5 to <18 years age subgroup indicated numerically greater HFMSE improvement of 2.45 (95% confidence interval: 0.42−4.49) for the OAV101 IT group compared with sham. These results are clinically significant, especially considering the progressive 2-point annual loss in function observed in untreated patients older than 5 years reported by Mercuri et al.22.

Of the AESI reported, hepatotoxicity AESI were observed in a similar percentage of participants for both the OAV101 IT and sham groups (9.3% versus 9.8%). Increases in transaminases (ALT or AST >2× ULN) were more frequent in the OAV101 IT group versus sham (17.3% versus 9.8%); however, most represented small increases greater than ULN, and all resolved by the end of Follow-Up Period 1. Total bilirubin did not exceed 1.5× ULN in any participant. There were no cases of Hy’s law.

In NHPs, microscopic neuropathology findings in DRG related to OAV101 IT administration were previously reported, albeit with supratherapeutic doses and different vectors in some cases12,13,14,15. DRG findings after OAV101 IT administration in cynomolgus monkeys were not related to electrophysiology changes and trended toward resolution after 52 weeks12. In STEER, peripheral sensory neuropathies and hypoesthesia and paresthesia were reported in two participants in the OAV101 IT group; one participant in the sham group reported paresthesia. The events in the OAV101 IT group required symptomatic treatment, and, in both cases, improvement and stabilization of symptoms were reported; however, symptoms were not completely resolved by the time of last study visit. For both participants, nerve conduction studies revealed decreasing SNAP amplitudes with relative preservation of conduction velocities in distributions consistent with sensory symptoms. In parallel, the distribution of affected areas remained stable or diminished. Taken together, these findings suggest a monophasic sensory axonopathy or sensory ganglionopathy. Interestingly, diminished vibration sense and proprioception were not observed by investigators after testing the two patients with sensory events, although nerve conduction study results confirmed large fiber involvement. Given the limited distribution of symptoms in both cases, it was not possible to discern between the two possible diagnoses.

Possible limitations of this study include broad inclusion of all patients regardless of baseline HFMSE and wide age range in the eligibility criteria. An observation period of 12 months may also not be sufficient to permit assessment of delayed AEs for OAV101 IT or to observe full benefit in motor function; hence, participants are provided an opportunity to participate in a long-term follow-up study (NCT05335876). In addition, the study monitoring and data collection were not sufficient to gather enough evidence to understand whether the sensory events were the result of DRG toxicity similar to that described in the NHP studies. As such, complete neurologic evaluation and other testing and/or symptom management should be considered based on the patient’s clinical presentation. Patients and caregivers should be informed about the signs and symptoms of peripheral sensory neuropathy and be advised to notify their physician promptly if such symptoms occur.

Conclusions

The efficacy and safety of OAV101 IT for SMA has been demonstrated in treatment-naive patients without the confounding effects of other therapies. The STEER study met its primary efficacy endpoint, demonstrating a statistically significant improvement in motor function for OAV101 IT compared with sham control. The overall safety findings were acceptable, with similar incidences of AEs, SAEs and AESI in the OAV101 IT and sham groups. All secondary efficacy endpoints favored OAV101 IT and supported the primary endpoint, although none achieved required thresholds for statistical significance per the prespecified multiple testing strategy. In summary, the results of the STEER study demonstrate clinical benefits across a broad SMA population with a wide range of ages and baseline motor function.

Methods

STEER was undertaken in accordance with the International Council for Harmonisation E6 Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice with the ethical principles in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by institutional review boards (IRBs) at all participating institutions (Institute Ethics Committee at Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi, India, and P.D. Hinduja Hospital and Medical Research Centre, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India; Rainbow Children’s Medicare Ethics Committee for Clinical Trials & Bioavailability–Bioequivalence Studies, Hyderabad, Telangana, India; Clinical Research Ethics Committee, Kolkata, West Bengal, India; Medical Research Ethics Committee, University of Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; Medical Research & Ethics Committee, Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia; Research Ethics Committee, King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board, B2, Singapore; Human Research Ethics, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa; Kaohsiung Medical University Chung-Ho Memorial Hospital IRB, Kaohsiung, Taiwan; Human Research Protection Unit, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; Ethics Committee in Biomedical Research of National Children’s Hospital, Hanoi, Vietnam; Ain Shams University Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo, Egypt; Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital, Beijing, China; Beijing Children’s Hospital Medical Ethics Committee, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China; Ethics Committee for Drug Clinical Trials of Peking, Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, China; Ethical Committee for Drug Clinical Trials of Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China; Medical Ethics Committee of Children’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China; IRB of Children’s Hospital to Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China; IRB of West China Second Hospital of Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan, China; Medical Ethics Committee of Shenzhen Children’s Hospital, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China; De Videnskabsetiske Komitéer for Region Hovedstaden, Copenhagen, Denmark; Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa Hospital Erasto Gaertner−Liga Paranaense de Combate ao Câncer, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil; Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa em Seres Humanos da Faculdade de Ciências Médicas−UNICAMP/SP, São Paulo, Brazil; Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa do Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil; Comité de Ética en Investigación del Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez, Mexico City, Mexico; Comité de Ética en Investigación del Antiguo Hospital Civil de Guadalajara Fray Antonio Alcalde, Guadalajara, Mexico; and Advarra, Maryland, USA). Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians (and assent as appropriate) before participation. The STEER study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05089656) and EudraCT (EMEA-002168-PIP01-M06).

Study design

STEER was a multicenter, randomized, sham-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of OAV101 IT (1.2 × 1014 vector genomes) for patients with SMA who were 2 to <18 years of age, treatment-naive and sitting but have never walked independently. The study comprised two periods: a 52-week Period 1 and a 12-week Period 2 (Supplementary Fig. 4). In Period 1, the basis for the primary analysis of this study, participants were randomized 3:2 to receive either OAV101 IT or a sham procedure and were followed up to week 52 (end of Period 1). After completing Period 1, eligible participants entered into Period 2, in which participants who received a sham procedure in Period 1 received OAV101 IT, and participants who received OAV101 IT received a sham procedure while maintaining blinding. Results from Period 1 of the study are reported herein based on the data cutoff date of 12 November 2024.

The STEER study aimed to enroll 125 participants to receive OAV101 IT (n ≈ 75) or sham procedure (n ≈ 50). Randomization was stratified by age and the highest pretreatment HFMSE score at screening as follows to ensure that both OAV101 IT and sham groups were balanced in terms of baseline characteristics of age and motor function: age 2 to <5 years, HFMSE score ≤15 or >15; age 5 to <13 years, HFMSE score ≤10 or >10; age 13 to <18 years, no stratification based on HFMSE score. Participants (and their caregivers), clinical evaluators who performed the HFMSE and the RULM assessments and study investigators were blinded.

Participants

Full eligibility criteria are described in the supplementary methods. Key inclusion criteria included diagnostic confirmation of 5q SMA, being naive to treatment for all SMN-targeting therapies, 2 to <18 years of age, onset of signs and symptoms ≥6 months of age and able to sit independently but never having had the ability to walk independently. Participants were excluded if they had elevated anti-AAV9 antibody titers (>1:50), scoliosis with a Cobb angle greater than 40° or severe contractures, contraindications for lumbar puncture procedure, active infections or hepatic dysfunction.

Treatment

OAV101 IT delivers the SMN transgene via an AAV9 vector and is identical to that used in the STRONG study and the current intravenous formulation. OAV101 IT was delivered as a single IT injection under sedation/anesthesia. Participants randomized to the sham group received a small needle prick on the lower back at the location where the lumbar puncture injection is normally made, also under sedation. Both procedures used an atraumatic spinal needle. After their procedures on study day 1, participants remained at the hospital for 24−48 hours for safety monitoring.

Participants randomized to OAV101 IT received prophylactic prednisolone (1 mg/kg per day), approximately 24 hours prior to dosing, to dampen the host immune response. Prednisolone was continued for 30 days and tapered over at least 4 weeks. Participants randomized to the sham procedure arm received placebo instead of prednisolone and followed the same administration protocol.

Primary, secondary and exploratory efficacy motor outcomes

Primary outcome was the change from baseline in HFMSE score at the end of Follow-Up Period 1 in the overall study population (2 to <18 years age group) (Supplementary Table 7). The HFMSE is a validated scale specifically designed to assess motor function in SMA and commonly used in clinical trials, natural history studies and clinical practice; it comprises a 33-item questionnaire (total score range, 0–66 points), with higher scores indicative of greater ability23,24,25.

Secondary outcomes were assessed in the overall study population (2 to <18 years age group) and the age subgroup of 2 to <5 years (Supplementary Table 7). For the 2 to <18 years age group, secondary outcomes included achievement of at least a 3-point improvement from baseline in HFMSE score (indicates improvement in at least two items4 and has been used as an endpoint in later-onset SMA16) and change from baseline in the RULM score at the end of Follow-Up Period 1. The RULM is a validated, SMA-specific outcomes measure that assesses motor performance in the upper limbs26,27. This scale has been used in clinical trials of SMA5 and consists of 19 items (total score range, 0–37 points), with higher scores reflecting better ability. The HFMSE and RULM were administered by trained and qualified site clinical evaluators (physical therapist, occupational therapist or national equivalent).

For the 2 to <5 years age subgroup, secondary outcomes included change from baseline in HFMSE score and RULM score and achievement of at least a 3-point improvement in HFMSE score at the end of Follow-Up Period 1 (Supplementary Table 7).

Exploratory efficacy outcomes included the following for the 5 to <18 years age subgroup: change from baseline in HFMSE score and change from baseline in RULM score at the end of Follow-Up Period 1 (Supplementary Table 7).

Safety outcomes

Safety was evaluated throughout the study, consisting of monitoring AEs, SAEs and AESI (Supplementary Table 7), vital signs, physical and neurologic examinations, laboratory assessments, echocardiogram, electrocardiogram, anthropometry and Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale.

Data analysis

STEER data analyses are described in the supplementary methods (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Novartis is committed to sharing with qualified external researchers access to patient-level data and supporting clinical documents from eligible studies. These requests are reviewed and approved by an independent review panel on the basis of scientific merit. All data provided are anonymized to respect the privacy of patients who have participated in the trial, in line with applicable laws and regulations.

This trial data availability is according to the criteria and process described at https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com/.

References

Prior, T.W., Leach, M.E. & Finanger, E.L. Spinal muscular atrophy. 2000, February 24 (updated 2024, September 19). in GeneReviews® (eds Adam, M.P. et al.) (Univ. Washington, 1993–2025).

Mercuri, E. et al. Spinal muscular atrophy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 8, 52 (2022).

Coratti, G. et al. Gain and loss of abilities in type II SMA: a 12-month natural history study. Neuromuscul. Disord. 30, 765–771 (2020).

Mercuri, E. et al. Patterns of disease progression in type 2 and 3 SMA: implications for clinical trials. Neuromuscul. Disord. 26, 126–131 (2016).

Biogen. Spinraza prescribing information. https://www.spinraza.com/content/dam/commercial/spinraza/caregiver/en_us/pdf/spinraza-prescribing-information.pdf (2024).

Genentech. Evrysdi prescribing information. https://www.gene.com/download/pdf/evrysdi_prescribing.pdf (2025).

Novartis Gene Therapies, Inc. Zolgensma prescribing information. https://www.novartis.com/us-en/sites/novartis_us/files/zolgensma.pdf (2025).

Varone, A., Esposito, G. & Bitetti, I. Spinal muscular atrophy in the era of newborn screening: how the classification could change. Front. Neurol. 16, 1542396 (2025).

Aragon-Gawinska, K., Mouraux, C., Dangouloff, T. & Servais, L. Spinal muscular atrophy treatment in patients identified by newborn screening: a systematic review. Genes (Basel) 14, 1377 (2023).

European Medicines Agency. Zolgensma summary of product characteristics. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/zolgensma

Finkel, R. S. et al. Intrathecal onasemnogene abeparvovec for sitting, nonambulatory patients with spinal muscular atrophy: phase I ascending-dose study (STRONG). J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 10, 389–404 (2023).

Tukov, F. F. et al. Single-dose intrathecal dorsal root ganglia toxicity of onasemnogene abeparvovec in cynomolgus monkeys. Hum. Gene Ther. 33, 740–756 (2022).

Hinderer, C. et al. Severe toxicity in nonhuman primates and piglets following high-dose intravenous administration of an adeno-associated virus vector expressing human SMN. Hum. Gene Ther. 29, 285–298 (2018).

Hordeaux, J. et al. Adeno-associated virus-induced dorsal root ganglion pathology. Hum. Gene Ther. 31, 808–818 (2020).

Van Alstyne, M. et al. Gain of toxic function by long-term AAV9-mediated SMN overexpression in the sensorimotor circuit. Nat. Neurosci. 24, 930–940 (2021).

Mercuri, E. et al. Nusinersen versus sham control in later-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 625–635 (2018).

Coratti, G. et al. Determining minimal clinically important differences in the Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale Expanded for untreated spinal muscular atrophy patients: an international study. Eur. J. Neurol. 31, e16309 (2024).

Pera, M. C. et al. Content validity and clinical meaningfulness of the HFMSE in spinal muscular atrophy. BMC Neurol. 17, 39 (2017).

McGraw, S. et al. A qualitative study of perceptions of meaningful change in spinal muscular atrophy. BMC Neurol. 17, 68 (2017).

Rouault, F. et al. Disease impact on general well-being and therapeutic expectations of European Type II and Type III spinal muscular atrophy patients. Neuromuscul. Disord. 27, 428–438 (2017).

Mercuri, E. et al. Safety and efficacy of once-daily risdiplam in type 2 and non-ambulant type 3 spinal muscular atrophy (SUNFISH part 2): a phase 3, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 21, 42−52 (2022).

Mercuri, E. et al. Long-term progression in type II spinal muscular atrophy: a retrospective observational study. Neurology 93, e1241–e1247 (2019).

Krosschell, K. J., Maczulski, J. A., Crawford, T. O., Scott, C. & Swoboda, K. J. A modified Hammersmith functional motor scale for use in multi-center research on spinal muscular atrophy. Neuromuscul. Disord. 16, 417–426 (2006).

Krosschell, K. J. et al. Reliability of the modified Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale in young children with spinal muscular atrophy. Muscle Nerve 44, 246–251 (2011).

Glanzman, A. M. et al. Validation of the Expanded Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale in spinal muscular atrophy type II and III. J. Child Neurol. 26, 1499–1507 (2011).

Mazzone, E. S. et al. Revised upper limb module for spinal muscular atrophy: development of a new module. Muscle Nerve 55, 869–874 (2017).

Pera, M. C. et al. Revised upper limb module for spinal muscular atrophy: 12 month changes. Muscle Nerve 59, 426–430 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the investigators, site coordinators and study teams and, most importantly, the patients, families and caregivers for their participation in these studies. The authors would also like to thank clinical consultant J. Salem for his substantive review of the manuscript.

This study was supported by Novartis Pharma AG, which was involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation and writing of all related reports and publications. Editorial and medical writing support was provided by M. Heitzer of Kay Square Scientific. This support was funded by Novartis Pharma AG.

The authors would like to acknowledge the following support staff at their institutions.

• Children’s Hospital of The King’s Daughters, Norfolk, VA, USA (Principal Investigator: C.M. Proud). Coordinators: E. Smith, M. Griggs and A. Walker. PT: E. Darling. DPT: H. Casper. OT: D. Cowcer.

• University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa (Principal Investigator: J.M. Wilmshurst). Sub-investigators: S. Nana, S. Raga, B.-L. Edwards and G. Norton. Site study coordinators: M. Botha and J. Martin. Plus additional support from colleagues in pulmonology, physiotherapy, cardiology, neurophysiology and colleagues in the unblinded team.

• Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand (Principal Investigator: O. Sanmaneechai). Co-investigators: R. Kongkasuwan, T. Ploypetch, P. Kulsirichawaroj, D. Songsaeng, P. Tovichien, S. Kanjanauthai, S. Viravan, P. Songarj, P. Chaweekulrat, P. Jaidee, W. Nuanta, S. Limpaninlachat and K. Akesittipaisarn. Site study coordinators: C. Apirukpanakhet, N. Maneesawat and N. Sereephaowong.

• All India Institute of Medical Science (AIIMS), New Delhi, India (Principal Investigator: S. Gulati). Sub-investigators: M. Kabra, B. Chakrabarty, G. Kamila and K. Sinha Deb. Study coordinators (blinded): S. Katoch; (unblinded): A. Ashik. Specialist consultants: Anesthesiologist: P. Khanna, Pulmonologist: K. Jat, ENT Specialist: P. Sagar, Cardiologist: S. Kumar Gupta.

• Peking University First Hospital/Beijing Children’s Hospital, Capital Medical University/Peking University First Hospital, Beijing, China (Principal Investigator: H. Xiong). We would like to extend our gratitude to colleagues in pulmonology, physiotherapy, cardiology, intensive care unit and anesthesiology as well as those in the unblinded team.

• Yoo Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore (Principal Investigator: S.K.H. Tay). Co-investigators: F. Wang, V. Han, M. T. C. Lim, R. Taylor, P. Singh and H. Tat Ong. Site study coordinators: R. Lee, V. Asogan and N. Su Htet Wynn.

• Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia/M. Kandiah Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Selangor, Malaysia (Principal Investigator: M.-K. Thong). Co-investigators: C.-Y. Fong, W.-K. Lim, L. Li and S.-K. Tae. Site study coordinators: S. Shaharudin and W. Muhammad Hazeeq bin Wan Alias. Plus many colleagues from various departments and the Clinical Investigations Centre, Universiti Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur.

• Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University/National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan (Principal Investigator: Y.-J. Jong). Sub-investigators: W.-C. Liang, J.-H. Hsu, Y.-C. Liu, H.-H. Shih, C.-H. Wang, W.-Y. Hsu and W.-L. Hsiao. Site study coordinator: Y.-H. Chou. In addition, we would like to extend our gratitude to colleagues in pulmonology, physiotherapy, cardiology, neurophysiology, hematology and anesthesiology as well as those in the unblinded team at Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Taiwan, for their invaluable support.

• King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (Principal Investigator: M. Al-Muhaizea). Sub-investigators: M. Abukhaled and E. Tous. Research coordinator: N. S. Alrushud.

• St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN, USA (Principal Investigator: R. S. Finkel). Study approval/site activation: S. H. Hughes and C. C. Quillivan.

• Vietnam National Children’s Hospital, Hanoi, Vietnam (Principal Investigators: D.C. Vũ and T. Minh Dien), Co-investigators: N. Ngoc Khanh, C. Thi Bich Ngoc, N. Thu Ha, D. Thi Thanh Mai, N. Thu Hang and B. Thi Huong. Pharmacists: P. Thu Ha and D. Thuy Anh. Hanoi University of Public Health, Hanoi, Vietnam (Principal Investigator: Vũ). Site study coordinators: N. Thi Lien, N. Thi Cam and N. Hoang Thu. Plus colleagues from various departments/centers: Pharmacy Department, Pediatric Cardiology Center, Center for Pediatric Neurology, Department of Imaging Diagnosis, Training and Research Institute for Child Health, as well as those in the unblinded and blinded teams.

• Hospital Tunku Azizah Paediatric Department, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (Principal Investigator: A. Rithauddin Mohamed). Former principal investigator: P. A/P Anandakrishnan. Blinded sub-investigators: D. Binti Abd Hadi, T. Yan Lian, L. Jun Xiong and S. Murugesu. Blinded main study coordinator: H. Mohd Yassim. Blinded study coordinators: S. Zubaidah Zulkhairi, P. Nur Najwa Binti Nor Azman and L. Shafiqah Sahul Hamid; Echologists: A. Bt Alias and J. Bawani. Physiotherapists: M. Azhari Bin Abdul Aziz and S. Mohd Shahardin. Study nurses: R. Ab Rahman, N. Fariza Binti Ramli, N. Fatiha Bt Othman and S. Dameema Mohd Zahari. Speech therapists: N. Shahima Sauhaimi and C. Kai Shuo. Radiologist: F. Nadrah Bt Mohd Nasir. Radiographer: N. Saliha Binti Abd Hadi. Laboratory personnel: N. Azlin Bin Anuar and A. Ishak. Unblinded sub-investigators: K. Gunasagaran, I. Zarina Binti Fakir Mohamed, T. Chee Sean and M. Jamil. Unblinded main study coordinator: M. Yusri Fauzi.

• Peerless Hospital Kolkata, Kolkata, West Bengal, India (Principal Investigator: S. Dey). Co-investigator: S. Sekhar. Research coordinator: D. De. Senior physiotherapist: K. Sarkar. Consultant physical medicine and rehabilitation: K. Chakraborty. Consultant cardiologist: S. Chaudhuri. Consultant anaesthetists: S. Bhattacharya and J. Sengupta. Consultant respiratory medicine: A. K. Sarkar. Site coordinators: S. Ghosal and R. Das.

• Rainbow Children’s Hospital, Hyderabad, India (Principal Investigator: R. Konanki). Study coordinator (blinded): S. Vaddadi. Physical therapist: A. Vemaraju. Study coordinator (unblinded): A. Gupta.

• P.D. Hinduja National Hospital and Medical Research Center, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India (Principal Investigator: N. Desai). Pulmonologist: R. Banka. CRC: P. Padhye. OT: U. Bhojne and F. Coutinho. Speech therapists: R. Dixit and P. Jadhav.

• Hospital das Clinicas da Faculdade de Medicina da USP Instituto Da Crianca, São Paulo, Brazil (Principal Investigator: E. Zanoteli). Sub-investigators: C. Gontijo Camelo, C. Matsui Júnior and R. de Holanda Mendonça. Speech therapist: M. Takaaci Gomes. Nurse practitioner: A.C. dos Santos Monteiro. Study coordinator: J. Caires de Oliveira Achili Ferreira. Physical therapists: G. Jorge Polido, J. Rodrigues Iannicelli and M. Cunha Artilheiro. Unblinded coordinator: F. Andrade Macaferri Fonseca Nunes. Pharmacist: T. Araki.

• Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland: Program Head: D. Grant; Biostatistics: N. Ballarini and S. Wen; Clinical Development: G. Williams, R. Bernardo Escudero, A. Misko, R. Baddam, A. Misiak-Pereira, M. Esquivel-Gaon and S. Sai Twarakavi; Clinical Operations: C. Pendergrass, M. Rissler, M. Kocun and T. Chevannes-Osborne; Data Management: D. Jaysing Sawant and V. Bhataiya. Publications: D. Wolff.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conceived or designed the study: S.T.-W. and R.S.F. Collected data: C.M.P., D.C.V., J.M.W., O.S., S.G., H.X., H.C.M., S.K.H.T., M.-K.T., A.P.B., A.B.O., Y.-J.J., M.A.A.-M. and A.W.L. Accessed and verified data: C.M.P., D.C.V., J.M.W., O.S., S.G., H.X., H.C.M., S.K.H.T., M.-K.T., A.P.B., A.B.O., Y.-J.J., M.A.A.-M., A.W.L., I.A. and R.P. Interpreted data: C.M.P., A.W.L., J.V., I.A., R.P. and R.S.F. Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: C.M.P., D.C.V., J.M.W., O.S., S.G., H.X., H.C.M., S.K.H.T., M.-K.T., A.P.B., A.B.O., Y.-J.J., M.A.A.-M., A.W.L., J.V., S.T.-W., I.A., R.P. and R.S.F.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Novartis Pharma AG sponsored this clinical trial. The authors declare the following competing interests. C.M.P. has served as a consultant for Novartis Gene Therapies, Inc./Novartis Pharma AG, Biogen and Sarepta; has served on a speaker’s bureau for Novartis Gene Therapies, Inc./Novartis Pharma AG and Biogen; and has received research support from Novartis Gene Therapies, Inc./Novartis Pharma AG, Biogen, Sarepta, PTC, CSL Behring, Scholar Rock and Catabasis. J.M.W. has received fees from Roche; serves on the national South African advisory boards for Novartis and Sanofi; and is chief editor for the Pediatric Neurology section of Frontiers in Neurology. O.S. has received research grants from Novartis and Thermo Fisher Scientific, received honoraria for lectures and speaker’s bureau from F. Hoffmann-La Roche and Novartis and serves as a board member of the Foundation to Eradicate Neuromuscular Diseases (FEND) and on an advisory panel for the Thai SMA group. S.G., H.X., H.C.M., S.K.H.T., M.-K.T., A.P.B., A.B.O., M.A.A.-M. and D.C.V. have no conflicts related to this work to disclose. Y.-J.J. has participated in clinical trials with Biogen, Novartis, Roche, PTC, Sarepta and Pfizer; received speaker and/or consulting fees from Biogen, Novartis, Roche and Pfizer; and received research grants from Biogen. A.W.L., J.V., S.T.-W., I.A. and R.P. are employees of Novartis and own stock/other equities. R.S.F. has received personal compensation for advisory board/data safety monitoring board participation from Astellas, Dyne, Italfarmaco, AveXis/Novartis Gene Therapies, Inc./Novartis Pharma AG, NS Pharma, Biogen, Catabasis, Ionis, Italfarmaco, ReveraGen, Roche/Genentech, Sarepta, Satellos and Scholar Rock; editorial fees from Elsevier for co-editing a neurology textbook; license fees from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; and research support from Biogen and Roche/Genentech. R.S.F. also participated as an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Novartis Gene Therapies, Inc./Novartis Pharma AG, Biogen, Catabasis, Dyne, Genethon, Italfarmaco, ReveraGen, Roche/Genentech, Sarepta and Scholar Rock.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Xiaofeng Wang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Jerome Staal, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

STEER Study Group–Primary Investigators, supplementary methods, supplementary results, Supplementary Tables 1−7 and Supplementary Figs. 1−5

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Proud, C.M., Vũ, D.C., Wilmshurst, J.M. et al. Intrathecal onasemnogene abeparvovec in treatment-naive patients with spinal muscular atrophy: a phase 3, randomized controlled trial. Nat Med (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04103-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04103-w