Abstract

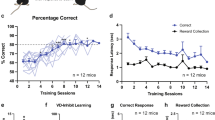

Learning to predict threat is essential, but equally important—yet often overlooked—is learning about the absence of threat. Here, by recording neural activity in two nucleus accumbens (NAc) glutamatergic afferents during aversive and neutral cues, we reveal sex-biased encoding of threat cue discrimination. In male mice, NAc afferents from the ventral hippocampus are preferentially activated by threat cues. In female mice, these ventral hippocampus–NAc projections are activated by both threat and nonthreat cues, whereas NAc afferents from medial prefrontal cortex are more strongly recruited by footshock and reliably discriminate threat from nonthreat. Chemogenetic pathway-specific inhibition identifies a double dissociation between ventral hippocampus–NAc and medial prefrontal cortex–NAc projections in cue-mediated suppression of reward-motivated behavior in male and female mice, despite similar synaptic connectivity. We suggest that these sex biases may reflect sex differences in behavioral strategies that may have relevance for understanding sex differences in risk of psychiatric disorders.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All code is available at https://github.com/BagotLab or described in the Methods.

References

Limpens, J. H. et al. Using conditioned suppression to investigate compulsive drug seeking in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 142, 314–324 (2014).

Gray, J. A. The neuropsychology of anxiety—an inquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system. Behav. Brain Sci. 5, 469–484 (1982).

Bach, D. R. et al. Human hippocampus arbitrates approach-avoidance conflict. Curr. Biol. 24, 541–547 (2014).

Britt, J. P. et al. Synaptic and behavioral profile of multiple glutamatergic inputs to the nucleus accumbens. Neuron 76, 790–803 (2012).

Goto, Y. & Grace, A. A. Limbic and cortical information processing in the nucleus accumbens. Trends Neurosci. 31, 552–558 (2008).

Goto, Y. & Grace, A. A. Dopaminergic modulation of limbic and cortical drive of nucleus accumbens in goal-directed behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 805–812 (2005).

Floresco, S. B. The nucleus accumbens: an interface between cognition, emotion, and action. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 66, 25–52 (2015).

Nicola, S. M. The nucleus accumbens as part of a basal ganglia action selection circuit. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 191, 521–550 (2007).

Gruber, A. J., Hussain, R. J. & O’Donnell, P. The nucleus accumbens: a switchboard for goal directed behaviors. PLoS ONE 4, e5062 (2009).

Kim, C. K. et al. Molecular and circuit-dynamical identification of top-down neural mechanisms for restraint of reward seeking. Cell 170, 1013–1027.e14 (2017).

Bagot, R. C. et al. Ventral hippocampal afferents to the nucleus accumbens regulate susceptibility to depression. Nat. Commun. 6, 7062 (2015).

Bittar, T. P. et al. Chronic stress induces sex-specific functional and morphological alterations in corticoaccumbal and corticotegmental pathways. Biol. Psychiatry 90, 194–205 (2021).

Muir, J. et al. Ventral hippocampal afferents to nucleus accumbens encode both latent vulnerability and stress-induced susceptibility. Biol. Psychiatry 88, 843–854 (2020).

Williams, E. S. et al. Androgen-dependent excitability of mouse ventral hippocampal afferents to nucleus accumbens underlies sex-specific susceptibility to stress. Biol. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.08.006 (2020).

Shansky, R. M. Are hormones a ‘female problem’ for animal research? Science 364, 825–826 (2019).

Williams, E. S., Mazei-Robison, M. & Robison, A. J. Sex differences in major depressive disorder (MDD) and preclinical animal models for the study of depression. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 14, a039198 (2022).

Wood, S. N. Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B Stat. Methodol. 73, 3–36 (2011).

Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Generalized additive models for medical research. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 4, 187–196 (1995).

French, S. J. & Totterdell, S. Hippocampal and prefrontal cortical inputs monosynaptically converge with individual projection neurons of the nucleus accumbens. J. Comp. Neurol. 446, 151–165 (2002).

O’Donnell, P. & Grace, A. A. Synaptic interactions among excitatory afferents to nucleus accumbens neurons: hippocampal gating of prefrontal cortical input. J. Neurosci. 15, 3622–3639 (1995).

Belujon, P. & Grace, A. A. Critical role of the prefrontal cortex in the regulation of hippocampus-accumbens information flow. J. Neurosci. 28, 9797–9805 (2008).

LeGates, T. A. et al. Reward behaviour is regulated by the strength of hippocampus-nucleus accumbens synapses. Nature 564, 258–262 (2018).

Piantadosi, P. T., Yeates, D. C. M. & Floresco, S. B. Prefrontal cortical and nucleus accumbens contributions to discriminative conditioned suppression of reward-seeking. Learn. Mem. 27, 429–440 (2020).

Yoshida, K. et al. Serotonin-mediated inhibition of ventral hippocampus is required for sustained goal-directed behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 770–777 (2019).

Calhoon, G. G. & O’Donnell, P. Closing the gate in the limbic striatum: prefrontal suppression of hippocampal and thalamic inputs. Neuron 78, 181–190 (2013).

Baratta, M. V. et al. Controllable stress elicits circuit-specific patterns of prefrontal plasticity in males, but not females. Brain Struct. Funct. 224, 1831–1843 (2019).

van Leeuwen, F. W., Caffe, A. R. & De Vries, G. J. Vasopressin cells in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis of the rat: sex differences and the influence of androgens. Brain Res. 325, 391–394 (1985).

Scudder, S. L. et al. Hippocampal-evoked feedforward inhibition in the nucleus accumbens. J. Neurosci. 38, 9091–9104 (2018).

Yu, J. et al. Nucleus accumbens feedforward inhibition circuit promotes cocaine self-administration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E8750–E8759 (2017).

Loijen, A. et al. Biased approach-avoidance tendencies in psychopathology: a systematic review of their assessment and modification. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 77, 101825 (2020).

Papini, M. R. & Bitterman, M. E. The two-test strategy in the study of inhibitory conditioning. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Process. 19, 342–352 (1993).

Foilb, A. R. et al. Sex differences in fear discrimination do not manifest as differences in conditioned inhibition. Learn. Mem. 25, 49–53 (2018).

Greiner, E. M. et al. Sex differences in fear regulation and reward-seeking behaviors in a fear-safety-reward discrimination task. Behav. Brain Res. 368, 111903 (2019).

Krueger, J. N. & Sangha, S. On the basis of sex: differences in safety discrimination vs. conditioned inhibition. Behav. Brain Res. 400, 113024 (2021).

Pellman, B. A. et al. Sexually dimorphic risk mitigation strategies in rats. eNeuro. https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0288-16.2017 (2017).

Felix-Ortiz, A. C. et al. The infralimbic and prelimbic cortical areas bidirectionally regulate safety learning during normal and stress conditions. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.05.539516 (2023).

Pignatelli, M. et al. Cooperative synaptic and intrinsic plasticity in a disynaptic limbic circuit drive stress-induced anhedonia and passive coping in mice. Mol. Psychiatry 26, 1860–1879 (2021).

McGinty, V. B. & Grace, A. A. Selective activation of medial prefrontal-to-accumbens projection neurons by amygdala stimulation and Pavlovian conditioned stimuli. Cereb. Cortex 18, 1961–1972 (2008).

Baeg, E. H. et al. Fast spiking and regular spiking neural correlates of fear conditioning in the medial prefrontal cortex of the rat. Cereb. Cortex 11, 441–451 (2001).

Zhang, X. et al. An emergent discriminative learning is elicited during multifrequency testing. Front. Neurosci. 13, 1244 (2019).

Martin-Fernandez, M. et al. Prefrontal circuits encode both general danger and specific threat representations. Nat. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-023-01472-8 (2023).

Farrell, M. R., Sengelaub, D. R. & Wellman, C. L. Sex differences and chronic stress effects on the neural circuitry underlying fear conditioning and extinction. Physiol. Behav. 122, 208–215 (2013).

Stark, R. et al. Influence of the stress hormone cortisol on fear conditioning in humans: evidence for sex differences in the response of the prefrontal cortex. Neuroimage 32, 1290–1298 (2006).

Zeidan, M. A. et al. Estradiol modulates medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala activity during fear extinction in women and female rats. Biol. Psychiatry 70, 920–927 (2011).

Shvil, E. et al. Sex differences in extinction recall in posttraumatic stress disorder: a pilot fMRI study. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 113, 101–108 (2014).

De Oca, B. M. et al. Distinct regions of the periaqueductal gray are involved in the acquisition and expression of defensive responses. J. Neurosci. 18, 3426–3432 (1998).

Weber, M. & Richardson, R. Pretraining inactivation of the caudal pontine reticular nucleus impairs the acquisition of conditioned fear-potentiated startle to an odor, but not a light. Behav. Neurosci. 118, 965–974 (2004).

Markowitz, J. E. et al. The striatum organizes 3D behavior via moment-to-moment action selection. Cell 174, 44–58.e17 (2018).

O’Donnell, P. et al. Modulation of cell firing in the nucleus accumbens. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 29, 157–175 (1999).

Duits, P. et al. Updated meta-analysis of classical fear conditioning in the anxiety disorders. Depress. Anxiety 32, 239–253 (2015).

Lissek, S. et al. Generalized anxiety disorder is associated with overgeneralization of classically conditioned fear. Biol. Psychiatry 75, 909–915 (2014).

Joormann, J. & Stanton, C. H. Examining emotion regulation in depression: a review and future directions. Behav. Res. Ther. 86, 35–49 (2016).

Wells, T. T. & Beevers, C. G. Biased attention and dysphoria: manipulating selective attention reduces subsequent depressive symptoms. Cogn. Emot. 24, 719–728 (2010).

Yang, W. et al. Attention bias modification training in individuals with depressive symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 49, 101–111 (2015).

Hodes, G. E. & Epperson, C. N. Sex differences in vulnerability and resilience to stress across the life span. Biol. Psychiatry 86, 421–432 (2019).

Cavanagh, A. et al. Symptom endorsement in men versus women with a diagnosis of depression: a differential item functioning approach. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 62, 549–559 (2016).

Sramek, J. J., Murphy, M. F. & Cutler, N. R. Sex differences in the psychopharmacological treatment of depression. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 18, 447–457 (2016).

Hodes, G. E. et al. Sex differences in nucleus accumbens transcriptome profiles associated with susceptibility versus resilience to subchronic variable stress. J. Neurosci. 35, 16362–16376 (2015).

Dana, H. et al. High-performance calcium sensors for imaging activity in neuronal populations and microcompartments. Nat. Methods 16, 649–657 (2019).

Gruene, T. M. et al. Sexually divergent expression of active and passive conditioned fear responses in rats. eLife 4, e11352 (2015).

Muir, J. et al. In vivo fiber photometry reveals signature of future stress susceptibility in nucleus accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology 43, 255–263 (2018).

Groth, A. & Ghil, M. Monte Carlo singular spectrum analysis (SSA) revisited: detecting oscillator clusters in multivariate datasets. J. Clim. 28, 7873–7893 (2015).

Kutlu, M. G. et al. Dopamine signaling in the nucleus accumbens core mediates latent inhibition. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 1071–1081 (2022).

Ma, J. et al. Divergent projections of the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus mediate the selection of passive and active defensive behaviors. Nat. Neurosci. 24, 1429–1440 (2021).

Scheggia, D. et al. Reciprocal cortico-amygdala connections regulate prosocial and selfish choices in mice. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 1505–1518 (2022).

Cai, X. et al. A D2 to D1 shift in dopaminergic inputs to midbrain 5-HT neurons causes anorexia in mice. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 646–658 (2022).

Gennatas, E. D. et al. Age-related effects and sex differences in gray matter density, volume, mass, and cortical thickness from childhood to young adulthood. J. Neurosci. 37, 5065–5073 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the Ludmer Centre for Neuroinformatics and Mental Health and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Project grant (grant no. 201709PJT-391173-BSA-CFAA-178116 (to R.C.B.)), a Canadian Institutes of Health Research graduate scholarship (grant no. 201810GSD-4221 05-DRA-CFAA-297096 (to J.M.)) and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Post-doctoral Fellowship (grant no. 202305ED0-509428-ECY-CFAA-248545 (to R.S.E.)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M. and R.C.B. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. J.M., E.S.I. and Y.-C.T. performed the experiments with assistance from S.W., R.S.E., V.C., K.W., S.G. and P.V. J.M., J.S., N.J.S. and E.S.I. analyzed and interpreted the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Neuroscience thanks Mikaela Laine and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Sex differences in shock encoding in mPFC-NAc.

Difference score comparing area under the curve 2 s after CS outcome subtracting area under the curve 2 s before outcome. (a) Females show elevated mPFC-NAc activity in response to CS+ outcome (footshock) compared to males (t15 = 2.83, n = 8, 9; p = 0.013) (b) but not in response to CS- outcome (no shock; t15 = 0.03, n = 8, 9; p = 0.97) while there are no sex differences in vHip-NAc activity in response to (c) CS+ (t14 = 0.39; n = 7, 9; p = 0.71) or (d) CS- outcome (t14 = 1.06, n = 7, 9; p = 0.31). All tests are unpaired, two-sided Student t-tests. Data are presented as mean values +/− SEM. #p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Modeling cue-elicited changes in neural activity.

To systematically profile fluorescence changes across the cue period we used generalized additive modeling (GAM). This generates a set of smooth functions to capture the influence of predictive variables, in this case, cue type, on neural activity while controlling for inter-individual variability. Given the nested structure of the data, this model provides a more sensitive representation of cue-elicited neural activity than simple group averaged traces. The resultant smooth functions can then be contrasted to identify differences across conditions. (a) GAM uses a sum of smooth functions to model contributions of a fixed variable, cue type, to variation in time series of neural activity recorded during individual cue presentations nested within individual animals, accounting for animal ID as a random variable. To probe differences in CS+ and CS- elicited neural activity across the cue, the difference function of the two smooth functions is calculated, with large non-zero values indicating epochs of maximum difference. GAM of (b-c) mPFC-NAc and (d, e) vHip-NAc revealed differences in CS+ and CS- elicited neural activity that emerge across training and identified 2 periods of maximal difference: 1 sec at cue onset and 8 sec preceding cue termination. Visual inspection of GAMs suggests most pronounced differences between CS+ and CS- at cue onset in (C) mPFC-NAc in females and in (D) vHip-NAc in males. Solid line represents the difference of smooth functions, and the shaded region is the SEM.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Pre-outcome suppression to CS+ cue.

Comparing the final 8 seconds prior to cue offset between CS+ and CS- reveals anticipatory suppression to CS+ cue. In females both (B) mPFC-NAc (Day 1: t8 = 2.76, n = 9, p = 0.02; Day 2: t8 = 2.41, n = 9, p = 0.04; Day 3: t8 = 4.65, n = 9, p = 0.0016) and (D) vHip-NAc (Day 1: t8 = 6.49, n = 9 p = 0.0002; Day 2: t8 = 2.91, n = 9 p = 0.019; Day 3: t7 = 3.88, n = 8, p = 0.006) exhibit greater suppression prior to CS+ offset compared to CS- across training. In males, a similar phenomena is observed, (A) trending in mPFC-NAc on day 1 (t7 = 2.15, n = 8, p = 0.068) and (C) significant in vHip-NAc (t5 = 3.86, n = 6, p = 0.01) and significant in both pathways in mid (mPFC: t7 = 2.73, n = 8, p = 0.027 vHip: t6 = 4.66, n = 7, p = 0.0035) and late training (mPFC: t7 = 4.19, n = 8, p = 0.0041 vHip: t6 = 3.157, n = 7, p = 0.02). All data are unpaired, two-sided Student t-tests. Data are presented as mean +/− SEM. #p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Accumbal afferents preferentially encode cue type in a sex-biased manner.

Relative to restricting to 1 s at cue onset (Fig. 4), using the full 30 s of cue-elicited neural activity increases classifier accuracy with all predictors performing above chance levels (all p < 0.05; Fisher’s exact test). Nevertheless, comparing performance across pathways confirms that a sex-bias remained with (B) mPFC-NAc significantly outperforming (D) vHip-NAc in females (p = 0.0025) with a converse trend in males for (C) vHip-NAc to outperform (A) mPFC-NAc (p = 0.09). #p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Accumbal afferent activity accounts for little variability in freezing.

In males, (a) mPFC-NAc activity accounts for less than 1% of variance in freezing, while (b) vHip-NAc activity at cue onset accounts for 2.5%. In females, (c) mPFC-NAc activity accounts for 8% of variance while (d) vHip-NAc activity accounts for 3%. Data was analyzed using linear mixed effects regression (see Supplementary Table 1). Line represents model fit of LMER and shading represents confidence interval.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Effect of mPFC-NAc and vHIP-NAc pathway inhibition on reward motivated behavior.

Difference score of suppression ratios (SRCS+-SRcs-) for mCherry control and hM4Di DREADD injected animals. (a) Male hM4Di and mCherry animals show similar differences in suppression following mPFC-NAc inhibition (t15 = 0.20, n = 10,7; p = 0.84), while (b) female hM4Di animals show significantly higher suppression compared to mCherry animals (t22 = 2.95, n = 14,10; p = 0.0073). (c) Male hM4Di animals show significantly higher suppression following vHip-NAc suppression compared to mCherry (t18 = 2.47, n = 10,10; p = 0.02) while(d) female hM4Di and mCherry animals do not differ (t12 = 0.003, n = 5,9; p = 0.998). Inhibition of NAc afferents does not directly modulate reward seeking. (A-D) Total active lever pressing during conditioned suppression test session across all animals tested. Grey dots indicate mice failing to reach lever press criteria on test day for inclusion in primary analyses, black dots indicated mice that reached criteria for inclusion. (e) Analysing all animals tested, mCherry males and hM4Di males in which mPFC-NAc is inhibited show similar levels of lever pressing (t20 = 0.14, n = 11,11; p = 0.89), while (f) hM4Di mPFC-NAc females show significantly reduced lever pressing compared to mCherry controls (t37 = 4.14, n = 15,24; p = 0.0002). Both (g) males (t18 = 0.09, n = 10,10; p = 0.93) (h) and females (t17 = 0.79, n = 8,11; p = 0.44) in which vHip-NAc is inhibited lever press to similar levels across the test session. Similarly, using a Fisher’s exact test to compare number of animals that did not meet lever pressing criteria, we find that hM4Di mPFC-NAc females show greater exclusion rates compared to mCherry controls (p = 0.0018), while hM4Di mPFC-NAc males (p = 0.31) and hM4Di vHip-NAc males (p = 0.99) and females (p = 0.60) show similar exclusion rates to controls. (i) A new cohort of female mice were trained to lever press for a food reward until reaching criteria on an RR20 delivery schedule without ever experiencing threat conditioning and then given C21 on a test day. (j) Both hM4Di females with DREADD inhibition of mPFC-NAc and mCherry controls lever press to similar levels on this task (t18 = 0.55, n = 10,10; p = 0.59) indicating that the overall reductions in lever pressing in (F) are mediated by history of threat exposure. All tests are unpaired two-tailed Student t-tests. Data are presented as mean values +/− SEM. #p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Viral expression is similar in excluded and included animals.

Comparison of viral expression in animals included in and excluded from analysis of suppression of reward seeking due to low levels of lever pressing. DREADD expression does not systematically vary between (a, b) female or male (c, d) mPFC-NAc or female vHip-NAc (e, f) excluded or included indicating that differences in targeting of DREADD expression are not the cause of low responding during testing. No vHip-NAc male mice were excluded. mPFC-NAc mCherry and DREADD mice did not differ in freezing either during (g) the period preceding the first cue (F(1, 35) = 0.02771, n = 14,1,10,14, p = 0.87) or (h) averaged across all 30 s pre-cue periods throughout the test session (F(1, 35) = 0.04192, n = 14,1,10,14, p = 0.84). Further, there was no evidence of differences between excluded and included mice. All tests are two-way RM ANOVAs with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. Data are presented as mean values +/− SEM.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Histological analysis illustrates similar extent of viral expression in male and female animals.

Schematics show viral expression pattern of DREADDs in (a, b) mPFC and (c, d) vHip in each animal overlayed on coronal plates.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Effect of C21 is not different in cells from male and female animals.

Bath application of C21 decreases membrane potential of (a) mPFC-NAc neurons expressing AAV-hM4Di in both male and female animals with no effect of sex (Ftreatment (1,9) = 33.17 n = 5,6 p = 0.0003; post hoc: pM = 0.0013, pF = 0.0061). (b) Representative traces illustrates effect of C21 (gray bar) in mPFC-NAc in males (upper trace) and females (lower trace). (c) The same effect was observed in vHip-NAc neurons expressing AAV-hM4Di in male and female animals again with no effect of sex (Ftreatment (1,11) = 36.12 n = 7,6 p < 0.0001; post-hoc: pM = 0.0007, pF = 0.0025). (d) Representative traces illustrates effect of C21 in vHip-NAc (gray bar) in males (upper trace) and females (lower trace). All tests are two-way RM Mixed effects analysis with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. Data are presented as mean values +/− SEM. #p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Traces show representative current clamp recordings.

Extended Data Fig. 10 No effect of sex on oEPSC amplitude.

ChR2 and ChrimsonR-elicited optically evoked EPSCs can be isolated at moderate light intensities. In cells expressing ChR2, optically evoked EPSC amplitude increases across intensities of blue (470 nm) but not orange (590 nm) light (Fint(10,120) = 2.518, n = 7,7, p = 0.009). In cells expressing (a) ChR2, or (b) ChrimsonR, optically evoked EPSC amplitude increases across intensities of orange (590 nm) and blue (470 nm) light but this increase is much stronger for orange light (Fint(10,88) = 3.70, n = 6,6, p = 0.0004). At moderate light intensities (150 mA) indicated by yellow rectangles, blue light only elicits an EPSC in ChR2- expressing cells and orange light only elicits an EPSC in ChrimsonR expressing cells demonstrating the compatibility of these optical tools for isolating pathway-specific oEPSCs. This moderate light intensity was used in all subsequent experiments. Amplitude of optically evoked EPSCs increases across increasing pulse widths in males and females with no effect of sex in (c) mPFC-NAc (Fsex(1,18) = 0.05, n = 9,11, p = 0.82; Fpulsewidth(1.137,19.96) = 55.41, n = 9,11, p < 0.0001) or (d) vHip-NAc (Fsex(1,18) = 0.07, n = 9,11, p = 0.80; Fpulsewidth(1.008,17.69) = 58.05, n = 9,11, p < 0.0001)). Independently analyzing oEPSC and oIPSC amplitude from E/I ratios presented in Fig. 6 confirms no effects of sex. (a–d) All tests are two-way mixed effects analyses. The average amplitude of oEPSC and oIPSC in D1 (EPSC: t25 = 1.40, n = 12,15, p = 0.17; IPSC: t25 = 1.94, n = 12,15, p = 0.06) (e, f) and D2 MSNs (EPSC: t22 = 0.16, n = 11,13, p = 0.87; IPSC: t24 = 0.24, n = 11,15, p = 0.81) (g, h) evoked by mPFC-NAc is not different between male and female animals. The average amplitude of oEPSC and oIPSC in D1 (EPSC: t25 = 0.88, n = 12,15, p = 0.39; IPSC: t25 = 0.30, n = 12,15, p = 0.76) (i, j) and D2 MSNs (EPSC: t22 = 0.85, n = 11,13, p = 0.40; IPSC: t22 = 0.77, n = 11,13, p = 0.45) (k, l) evoked by mPFC-NAc and vHip-NAc is not different between male and female animals. (e–l) All tests are unpaired, two-tailed Student t-tests. Data are presented as mean values +/− SEM.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Table 1. Relationship between neural activity at cue onset and freezing behavior. χ2 and P values for comparisons of model with no fixed variable (random variable only) and a model with the indicated variable as a fixed variable as well as a random variable (see the Methods for details). In females, vHip–NAc activity at cue onset and mPFC–NAc activity at cue onset significantly improve a null model and explain 3% and 8% of variance, respectively. In males, neither vHip–NAc nor mPFC–NAc activity at cue onset improves a null model and explains 0.1% and 3% of variance, respectively.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Source data for KNN model.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Source data for GAM.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Muir, J., Iyer, E.S., Tse, YC. et al. Sex-biased neural encoding of threat discrimination in nucleus accumbens afferents drives suppression of reward behavior. Nat Neurosci 27, 1966–1976 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-024-01748-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-024-01748-7

This article is cited by

-

Neurobiology of resilience to early life stress

Neuropsychopharmacology (2026)

-

Reward integration in prefrontal-cortical and ventral-hippocampal nucleus accumbens inputs cooperatively modulates engagement

Nature Communications (2025)

-

The psychoplastogen tabernanthalog induces neuroplasticity without proximate immediate early gene activation

Nature Neuroscience (2025)