Abstract

A nucleotide repeat expansion (NRE) (GGGGCC)n within the first annotated intron of the C9orf72 (C9) gene is a common cause of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD). While previous studies have shown that C9 NRE produces several toxic dipeptide repeat (DPR) proteins, the mechanism by which an intronic RNA segment can access the cytoplasmic translation machinery remains unclear. By selectively capturing and sequencing NRE-containing RNAs (NRE-capture-seq) from patient-derived fibroblasts and neurons, we found that, in contrast to previous models, C9 NRE is retained as part of an extended exon 1 due to the usage of various downstream alternative 5′ splice sites. These aberrant splice isoforms accumulate in C9-ALS/FTD brains, and their production is promoted by serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 1 (SRSF1). Antisense oligonucleotides targeting either SRSF1 or the aberrant C9 splice isoforms reduced the levels of DPR. Together, our findings revealed a crucial role of aberrant splicing in the biogenesis of NRE-containing RNAs and demonstrated potential therapeutic strategies to target these pathogenic transcripts.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Total RNA-seq and NRE-capture-seq data are available in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE247790. Raw data (FASTQ) and aligned BAM files of postmortem tissue RNA-seq data are available through Target ALS (https://dataengine.targetals.org/). RNA-seq data from neuronal nuclei with and without TDP-43 are available in GEO under accession number GSE126543. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Custom codes used in this study are available upon request.

References

Depienne, C. & Mandel, J. L. 30 years of repeat expansion disorders: what have we learned and what are the remaining challenges? Am. J. Hum. Genet. 108, 764–785 (2021).

Paulson, H. Repeat expansion diseases. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 147, 105–123 (2018).

Malik, I., Kelley, C. P., Wang, E. T. & Todd, P. K. Molecular mechanisms underlying nucleotide repeat expansion disorders. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 589–607 (2021).

Bunting, E. L., Hamilton, J. & Tabrizi, S. J. Polyglutamine diseases. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 72, 39–47 (2022).

Mohan, A., Goodwin, M. & Swanson, M. S. RNA–protein interactions in unstable microsatellite diseases. Brain Res. 1584, 3–14 (2014).

Wojciechowska, M. & Krzyzosiak, W. J. Cellular toxicity of expanded RNA repeats: focus on RNA foci. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 3811–3821 (2011).

Nguyen, L., Cleary, J. D. & Ranum, L. P. W. Repeat-associated non-ATG translation: molecular mechanisms and contribution to neurological disease. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 42, 227–247 (2019).

Zu, T. et al. Non-ATG-initiated translation directed by microsatellite expansions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 260–265 (2011).

Banez-Coronel, M. et al. RAN translation in Huntington disease. Neuron 88, 667–677 (2015).

Todd, P. K. et al. CGG repeat-associated translation mediates neurodegeneration in fragile X tremor ataxia syndrome. Neuron 78, 440–455 (2013).

Zu, T. et al. RAN translation regulated by muscleblind proteins in myotonic dystrophy type 2. Neuron 95, 1292–1305 (2017).

Zu, T. et al. RAN proteins and RNA foci from antisense transcripts in C9ORF72 ALS and frontotemporal dementia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, E4968–E4977 (2013).

Mori, K. et al. The C9orf72 GGGGCC repeat is translated into aggregating dipeptide-repeat proteins in FTLD/ALS. Science 339, 1335–1338 (2013).

Gendron, T. F. et al. Antisense transcripts of the expanded C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat form nuclear RNA foci and undergo repeat-associated non-ATG translation in c9FTD/ALS. Acta Neuropathol. 126, 829–844 (2013).

Kwon, I. et al. Poly-dipeptides encoded by the C9orf72 repeats bind nucleoli, impede RNA biogenesis, and kill cells. Science 345, 1139–1145 (2014).

Jovicic, A. et al. Modifiers of C9orf72 dipeptide repeat toxicity connect nucleocytoplasmic transport defects to FTD/ALS. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1226–1229 (2015).

Lopez-Gonzalez, R. et al. Poly(GR) in C9ORF72-related ALS/FTD compromises mitochondrial function and increases oxidative stress and DNA damage in iPSC-derived motor neurons. Neuron 92, 383–391 (2016).

Shi, K. Y. et al. Toxic PRn poly-dipeptides encoded by the C9orf72 repeat expansion block nuclear import and export. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E1111–E1117 (2017).

Moens, T. G. et al. C9orf72 arginine-rich dipeptide proteins interact with ribosomal proteins in vivo to induce a toxic translational arrest that is rescued by eIF1A. Acta Neuropathol. 137, 487–500 (2019).

White, M. R. et al. C9orf72 poly(PR) dipeptide repeats disturb biomolecular phase separation and disrupt nucleolar function. Mol. Cell 74, 713–728 (2019).

Sun, Y., Eshov, A., Zhou, J., Isiktas, A. U. & Guo, J. U. C9orf72 arginine-rich dipeptide repeats inhibit UPF1-mediated RNA decay via translational repression. Nat. Commun. 11, 3354 (2020).

Mizielinska, S. et al. C9orf72 repeat expansions cause neurodegeneration in Drosophila through arginine-rich proteins. Science 345, 1192–1194 (2014).

Renton, A. E. et al. A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 72, 257–268 (2011).

DeJesus-Hernandez, M. et al. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 72, 245–256 (2011).

Gitler, A. D. & Tsuiji, H. There has been an awakening: emerging mechanisms of C9orf72 mutations in FTD/ALS. Brain Res. 1647, 19–29 (2016).

Gendron, T. F. & Petrucelli, L. Disease mechanisms of C9ORF72 repeat expansions. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 8, a024224 (2018).

Conlon, E. G. et al. The C9ORF72 GGGGCC expansion forms RNA G-quadruplex inclusions and sequesters hnRNP H to disrupt splicing in ALS brains. eLife 5, e17820 (2016).

Loveland, A. B. et al. Ribosome inhibition by C9ORF72-ALS/FTD-associated poly-PR and poly-GR proteins revealed by cryo-EM. Nat. Commun. 13, 2776 (2022).

Lee, P. J., Yang, S., Sun, Y. & Guo, J. U. Regulation of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in neural development and disease. J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 269–281 (2021).

Xu, W. et al. Reactivation of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay protects against C9orf72 dipeptide-repeat neurotoxicity. Brain 142, 1349–1364 (2019).

Freibaum, B. D. et al. GGGGCC repeat expansion in C9orf72 compromises nucleocytoplasmic transport. Nature 525, 129–133 (2015).

Van ‘t Spijker, H. M. et al. Ribosome profiling reveals novel regulation of C9ORF72 GGGGCC repeat-containing RNA translation. RNA 28, 123–138 (2022).

Niblock, M. et al. Retention of hexanucleotide repeat-containing intron in C9orf72 mRNA: implications for the pathogenesis of ALS/FTD. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 4, 18 (2016).

Van Blitterswijk, M. et al. Novel clinical associations with specific C9ORF72 transcripts in patients with repeat expansions in C9ORF72. Acta Neuropathol. 130, 863–876 (2015).

Wang, S. et al. Nuclear export and translation of circular repeat-containing intronic RNA in C9orF72-ALS/FTD. Nat. Commun. 12, 4908 (2021).

Engreitz, J. M. et al. RNA–RNA interactions enable specific targeting of noncoding RNAs to nascent pre-mRNAs and chromatin sites. Cell 159, 188–199 (2014).

Gilbert, J. W. et al. Identification of selective and non-selective C9ORF72 targeting in vivo active siRNAs. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 35, 102291 (2024).

Cabrera, G. T. et al. Artificial microRNA suppresses C9ORF72 variants and decreases toxic dipeptide repeat proteins in vivo. Gene Ther. 31, 105–118 (2024).

Andrade, N. S. et al. Dipeptide repeat proteins inhibit homology-directed DNA double strand break repair in C9ORF72 ALS/FTD. Mol. Neurodegener. 15, 13 (2020).

Valencia, P., Dias, A. P. & Reed, R. Splicing promotes rapid and efficient mRNA export in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 3386–3391 (2008).

Maury, Y. et al. Combinatorial analysis of developmental cues efficiently converts human pluripotent stem cells into multiple neuronal subtypes. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 89–96 (2015).

Tam, O. H. et al. Postmortem cortex samples identify distinct molecular subtypes of ALS: retrotransposon activation, oxidative stress, and activated glia. Cell Rep. 29, 1164–1177 (2019).

Liu, E. Y. et al. Loss of nuclear TDP-43 is associated with decondensation of LINE retrotransposons. Cell Rep. 27, 1409–1421 (2019).

Younis, I. et al. Rapid-response splicing reporter screens identify differential regulators of constitutive and alternative splicing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 1718–1728 (2010).

Isiktas, A. U., Eshov, A., Yang, S. & Guo, J. U. Systematic generation and imaging of tandem repeats reveal base-pairing properties that promote RNA aggregation. Cell Rep. Methods 2, 100334 (2022).

Conlon, E. G. et al. Unexpected similarities between C9ORF72 and sporadic forms of ALS/FTD suggest a common disease mechanism. eLife 7, e37754 (2018).

Prudencio, M. et al. Distinct brain transcriptome profiles in C9orf72-associated and sporadic ALS. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1175–1182 (2015).

Xu, Z. et al. Expanded GGGGCC repeat RNA associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia causes neurodegeneration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 7778–7783 (2013).

Donnelly, C. J. et al. RNA toxicity from the ALS/FTD C9ORF72 expansion is mitigated by antisense intervention. Neuron 80, 415–428 (2013).

Cooper-Knock, J. et al. Sequestration of multiple RNA recognition motif-containing proteins by C9orf72 repeat expansions. Brain 137, 2040–2051 (2014).

Mori, K. et al. hnRNP A3 binds to GGGGCC repeats and is a constituent of p62-positive/TDP43-negative inclusions in the hippocampus of patients with C9orf72 mutations. Acta Neuropathol. 125, 413–423 (2013).

Celona, B. et al. Suppression of C9orf72 RNA repeat-induced neurotoxicity by the ALS-associated RNA-binding protein Zfp106. eLife 6, e19032 (2017).

Haeusler, A. R. et al. C9orf72 nucleotide repeat structures initiate molecular cascades of disease. Nature 507, 195–200 (2014).

Bajc Cesnik, A. et al. Nuclear RNA foci from C9ORF72 expansion mutation form paraspeckle-like bodies. J. Cell Sci. 132, jcs224303 (2019).

Denichenko, P. et al. Specific inhibition of splicing factor activity by decoy RNA oligonucleotides. Nat. Commun. 10, 1590 (2019).

Hautbergue, G. M. et al. SRSF1-dependent nuclear export inhibition of C9ORF72 repeat transcripts prevents neurodegeneration and associated motor deficits. Nat. Commun. 8, 16063 (2017).

Castelli, L. M. et al. SRSF1-dependent inhibition of C9ORF72-repeat RNA nuclear export: genome-wide mechanisms for neuroprotection in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol. Neurodegener. 16, 53 (2021).

Ben-Dor, I., Pacut, C., Nevo, Y., Feldman, E. L. & Reubinoff, B. E. Characterization of C9orf72 haplotypes to evaluate the effects of normal and pathological variations on its expression and splicing. PLoS Genet. 17, e1009445 (2021).

Green, K. M. et al. RAN translation at C9orf72-associated repeat expansions is selectively enhanced by the integrated stress response. Nat. Commun. 8, 2005 (2017).

Rothstein, J. D. et al. G2C4 targeting antisense oligonucleotides potently mitigate TDP-43 dysfunction in human C9orf72 ALS/FTD induced pluripotent stem cell derived neurons. Acta Neuropathol. 147, 1 (2023).

Anderson, R. et al. CAG repeat expansions create splicing acceptor sites and produce aberrant repeat-containing RNAs. Mol. Cell 84, 702–714 (2024).

Sathasivam, K. et al. Aberrant splicing of HTT generates the pathogenic exon 1 protein in Huntington disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 2366–2370 (2013).

Shah, S. et al. Antisense oligonucleotide rescue of CGG expansion-dependent FMR1 mis-splicing in fragile X syndrome restores FMRP. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2302534120 (2023).

Sznajder, L. J. et al. Intron retention induced by microsatellite expansions as a disease biomarker. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 4234–4239 (2018).

McEachin, Z. T. et al. Chimeric peptide species contribute to divergent dipeptide repeat pathology in c9ALS/FTD and SCA36. Neuron 107, 292–305 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Ferguson, W. Gilbert, P. Gopal, A. Horwich, J. Humphrey, A. Isaacs, Z. McEachin, P. Miura, K. Neugebauer, J. Steitz, S. Strittmatter, C. Thoreen, P. Todd and members of the Guo lab for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript. Postmortem tissue bulk RNA-seq data were generated and shared by the New York Genome Center for Genomics of Neurodegenerative Diseases and the Target ALS Human Postmortem Tissue Core. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH grants DP2 GM132930, R35 GM152208) and a McKnight Neurobiology of Brain Disorders Award (all to J.U.G.). High-performance computing at the Yale Center for Genome Analysis is supported by NIH (grant S10OD030363-01A1). S.Y. and D.W. were supported by training grant T32 NS041228 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. J.M.S.S., M.A., T.A. and J.D.P. were supported by the Yale Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (NIH grant P30 AG066508). J.U.G. is a New York Stem Cell Foundation-Robertson Investigator.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y. and J.U.G. conceived the study and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. S.Y. conducted most experiments and analyzed the results. D.W. conducted RT-qPCR analysis in iPSCs and MNs. U.S. and A.M.V. performed DPR immunoassays under the supervision of T.G. J.M.S.S., M.A., T.A. and J.D.P. performed iPSC culture and MN differentiation. J.Z. assisted in reporter experiments.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Yale University has filed a patent application based on this work. J.U.G. is a consultant for Corsalex, which was not involved in this project. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Neuroscience thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Reproducibility of cytoplasmic NRE-capture-seq between biological replicates.

Quantification of normalized read counts per gene from NRE-capture-seq. Left, comparison between two C9 NRE− fibroblast cell lines. Right, comparison between two C9 NRE+ fibroblast cell lines. C9orF72 is indicated in red. Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) are shown.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Replication and validation of cytoplasmic NRE-capture-seq.

(a) Read coverages of FB503 and FB506 cytoplasmic RNA inputs (top two tracks) and NRE-captured RNAs (bottom two tracks). (b) Schematics of RT-qPCR primers used in (c) and (d). (c) RT-qPCR quantification of the enrichment of aberrant Ex1c-Ex2 splice junction by NRE-capture, comparing C9 NRE+ and NRE− samples. (d) RT-qPCR quantification of siRNA knockdown efficiency in C9 NRE+ fibroblasts. siNT, non-targeting siRNA. siEx2 1 and 2, two siRNAs targeting C9orF72 exon 2. Data represent mean ± s.d. n = 2 biological replicates.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Replication of nuclear NRE-RAP-seq in FB506 fibroblasts.

Read coverage of FB506 nuclear RNA input (top) and NRE-captured RNAs (bottom). Top 10 splice junctions within and near intron 1 detected in NRE-capture-seq results are drawn. RPM, reads per million.

Extended Data Fig. 4 C9 aberrant splicing in C9 NRE+ iPSCs and MNs.

(a) Representative image of neuronal marker immunofluorescence. Scale bars, 20 µm. (b) RT-qPCR quantification of the Ex1c–Ex2 splice junction (left) and the Ex2–Ex3 splice junction (right), comparing C9 NRE+ and C9 NRE− iPSCs. (c) RT-qPCR quantification of the NRE-flanking region (left) and the Ex1c–Ex2 splice junction (right) in NRE-captured RNAs, comparing C9 NRE+ and C9 NRE− MNs, normalized to the value of C9 NRE− MN sample. (d) RT-qPCR quantification of ASO knockdown efficiency in C9 NRE+ fibroblasts. NT, nontargeting ASO. Ex1c–Ex2, ASO targeting Ex1c–Ex2 splice junction. Data represent mean ± s.d. n = 2 biological replicates.

Extended Data Fig. 5 C9 aberrant splicing in C9 NRE+ neuronal nuclei with and without TDP-43.

Normalized counts of reads containing Ex1b–Ex2, Ex1c–Ex2, and Ex1d–Ex2 splice junctions, comparing neuronal nuclei samples with and without loss of TDP-43. RNA-seq data (GSE126543) of ref. 43. The lower hinge, midline, and upper hinge of each box correspond to the first quartile, median, and third quartile, respectively. Upper and lower whiskers extend from the hinge to the maximal or minimal values, respectively, no further than 1.5 times the inter-quartile range. P values, two-tailed ratio t tests.

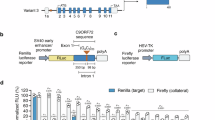

Extended Data Fig. 6 Impact of cryptic splicing on luciferase activities of repeat-containing reporters.

(a) Normalized activities of dual-luciferase from in vitro transcribed reporters with no NRE and (GGGGCC)33 insert. Data represent mean ± s.d. n = 7 biological replicates. P value, two-tailed ratio t test. (b) Normalized activities of dual-luciferase from original reporter and J1-mutated reporter (top, mutation shown in orange) with no NRE and (GGGGCC)33 insert. n = 3 biological replicates. P values, two-tailed ratio t tests.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Validation of SRSF1 knockdown.

(a) Western blot of SRSF1 in C9 NRE+ fibroblasts transfected with non-targeting (NT) siRNAs and a pool of four siRNAs targeting SRSF1 (S1). (b) RT-PCR quantification of known SRSF1 splicing targets in C9 NRE+ fibroblasts transfected with non-targeting (NT) siRNAs and a pool of four siRNAs targeting SRSF1 (S1). Data represent mean ± s.d. n = 3 biological replicates. P values, two-tailed ratio t tests.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Effect of SRSF1 knockdown on endogenous C9 NRE and repeat-containing reporter mRNAs.

(a) RT-qPCR quantification of the relative abundance of NRE-flanking region and Ex1c–Ex2 isoform after SRSF1 knockdown in C9 NRE− fibroblasts. Data represent mean ± s.d. n = 3 biological replicates. P values, two-tailed ratio t tests. (b) RT-qPCR quantification of the nucleocytoplasmic distribution of J1-mutated (GGGGCC)33 reporter transcripts (top, mutation shown in orange) in siRNA-treated HEK293T cells. S1, a pool of siRNAs targeting SRSF1 transcripts. Data represent mean ± s.d. n = 3 biological replicates. P values, two-tailed ratio t tests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–3.

Source data

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Unprocessed western blot and agarose gel images.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g., a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, S., Wijegunawardana, D., Sheth, U. et al. Aberrant splicing exonizes C9orf72 repeat expansion in ALS/FTD. Nat Neurosci 28, 2034–2043 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02039-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02039-5

This article is cited by

-

Enhanced hybridization-proximity labeling discovers protein interactomes of single RNA molecules

Nature Communications (2025)