Abstract

Cortical neurons projecting to the same target area may form specialized population codes to transmit information, but whether and how they do so remains unclear. We used calcium imaging in mouse posterior parietal cortex, retrograde labeling and statistical multivariate models to address this question during a delayed match-to-sample task in virtual reality. We found that neurons projecting to the same area have elevated pairwise activity correlations. These correlations are structured as information-limiting and information-enhancing motifs that shape interaction networks and collectively enhance information about the mouse’s choice beyond what is contributed by pairwise interactions. This network structure is unique to subpopulations that project to the same target and was not observed in surrounding neural populations with unidentified projections. Furthermore, this structure is only present when mice make correct, but not incorrect, behavioral choices. Therefore, cortical neurons comprising an output pathway form a population code with a unique correlation structure that enhances population-level information to guide accurate behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

A fundamental component of neural computation is how populations of neurons encode and transmit information to downstream brain areas1,2. Each cortical area communicates with many areas and contains a heterogeneous population of neurons that project to distinct downstream targets3,4,5,6. For the transmission of information between brain areas, the relevant neural codes are likely formed by populations of neurons that communicate with the same downstream target area, allowing their activity to be read out collectively. However, in most studies of neural population codes, populations have been analyzed without the knowledge of whether the cells project to the same target. It is, therefore, an open question of what principles underlie coding in populations of neurons that project to the same target area.

The information encoded in a population of neurons is affected by correlations between the activity of different neurons. Experimental and theoretical works have demonstrated how the correlations in activity between pairs of neurons can either enhance the population’s information, due to synergistic neuron–neuron correlations, or increase redundancy between neurons, which establishes robust transmission but limits the information encoded7. Most of this understanding arises from considerations of typical or average pairwise correlation values in populations. However, recent work reports that pairwise correlations in large populations can take on additional network structures, such as hubs of redundant or synergistic interactions8,9,10. Also, theoretical studies propose that a network-level structure of pairwise correlations may enhance neural population information11. Notably, whether projection pathways have network-level structures that enhance the information encoded in the projection pathway or aid their transmission to other brain areas has not been studied.

We studied the population codes in projection pathways between cortical areas in the posterior parietal cortex (PPC). PPC is a sensory-motor interface involved in decision-making tasks, including those involved in navigation12,13,14,15,16,17,18. PPC has heterogeneous activity profiles, including cells encoding various sensory modalities, locomotor movements and cognitive signals, such as spatial and choice information12,19,20,21,22. PPC is densely interconnected with cortical and subcortical regions in a network containing retrosplenial cortex (RSC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC)23. In addition, population codes in PPC contain correlations between neurons that benefit behavior24,25,26. Here we study PPC in a flexible navigation-based decision-making task because navigation decisions require the coordination of multiple brain areas to integrate signals across areas and also because PPC activity is necessary for mice to solve navigation decision tasks12,27,28,29.

We developed statistical multivariate modeling methods to investigate the population codes in cells sending axonal projections to the same target. We discovered that, in PPC neurons projecting to the same target, pairwise correlations are stronger and arranged into a specialized network structure of interactions. This structure consists of pools of neurons with enriched within-pool and reduced across-pool information-enhancing (IE) interactions, with respect to a randomly structured network. This structure enhances the amount of information about the mouse’s choice encoded by the population, with proportionally larger contributions for larger population sizes. Remarkably, this IE structure is only present in populations of cells projecting to the same target, and not in neighboring populations with unidentified outputs. Such structure is present when mice make correct choices, but not when they make incorrect choices. We propose that specialized network structures in PPC populations, which comprise an output pathway, enhance signal propagation in a manner that may facilitate accurate decision-making.

Results

A delayed match-to-sample task that isolates components of flexible navigation decisions

We developed a delayed match-to-sample task using navigation in a virtual reality T-maze (Fig. 1a)27. The T-stem contained a black or white sample cue followed by a delay maze segment with identical visual patterns on every trial. When mice passed a specific location, a test cue was revealed as a white tower in the left T-arm and a black tower in the right T-arm, or vice versa. The sample cue and test cue were chosen randomly and independently in each trial, and the two types of each cue defined four trial types. Mice received rewards when they turned into the T-arm whose color matched the sample cue. Thus, mice combined a memory of the sample cue with the test cue identity to choose a turn direction at the T-intersection. After training, mice performed this task with approximately 80% accuracy (Extended Data Fig. 1a,b). Incorrect trials occurred interleaved with correct trials at a relatively constant rate throughout the session, suggesting that errors were due to inaccurate decision-making rather than disengagement (Extended Data Fig. 1c).

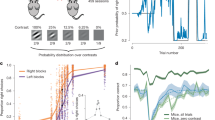

a, Schematic of a delayed match-to-sample task in virtual reality. b, Retrograde virus injections to label PPC neurons projecting to ACC, RSC and contralateral PPC (cPPC). Images are 250 × 350 μm. c, Depth distribution of PPC neurons projecting to different areas. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. over mice. d, Normalized mean deconvolved calcium traces of PPC neurons sorted based on the cross-validated peak time. Vertical gray lines represent onsets of sample cue, delay, test cue, turn into T-arms and reward. Gray dashed lines correspond to 1 s before turn and 0.5 s before reward. Color bar shows normalized mean deconvolved calcium intensity (a.u.). e, Cumulative distribution of the peak activity times for neurons. Compared to nonlabeled population, ***P < 0.001 for ACC-projecting (blue) and RSC-projecting (green) neurons, P = 0.13 for cPPC-projecting (red) neurons; two-sample KS-test. Error bars are s.e.m. computed from bootstrapping. f, Mean ± s.e.m. deconvolved calcium activity of different populations. Nonlabeled neurons are shown in black. g, Mean ± s.e.m. deconvolved calcium activity of example neurons with different encoding properties are shown in different trial conditions. Each trace corresponds to a trial type with a given sample cue and test cue in correct (green choice arrow) or incorrect (red choice arrow) trials. Neurons 1 to 4 encode the sample cue, the test cue, the left–right turn direction (choice) and the reward direction, respectively. Neuron 5 is active in only one of the four trial conditions, both in correct and incorrect trials, and thus encodes multiple task variables. Each subpanel contains four traces, corresponding to the four trial types. Some traces are hidden if they contain deconvolved calcium activity values of zero. Nonlabeled, n = 2,506 cells; cPPC projection, n = 93 cells; RSC projection, n = 127 cells; ACC projection, n = 134 cells. a.u., arbitrary units.

We used two-photon calcium imaging to measure the activity of hundreds of neurons simultaneously in layer 2/3 of PPC. We injected retrograde tracers conjugated to fluorescent dyes of different colors to identify neurons with axonal projections to ACC, RSC and contralateral PPC (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1d,g). These areas are major recipients of projections from layer 2/3 PPC neurons4, and the ACC–RSC–PPC network is important for navigation-based decision tasks29,30. The PPC neurons projecting to ACC, RSC and contralateral PPC were intermingled, except that ACC-projecting neurons were enriched in superficial layer 2/3 (Fig. 1c). Neurons projecting to the same area were slightly closer in anatomical space than in unlabeled neurons (Extended Data Fig. 1f). Neurons labeled with multiple retrograde tracers were not observed.

Neurons were transiently active during task trials with different neurons active at different times, and the activity of the population tiled the trial12 (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 1h). ACC-projecting cells had higher activity early in the trial, while RSC-projecting cells had higher activity later. Contralateral PPC-projecting neurons had more uniform activity across the trial (Fig. 1e,f). These differences in activity levels across the trial suggest that neurons projecting to different targets could contribute to different stages of information processing (Extended Data Fig. 3a). They could encode the sample cue (neuron 1; Fig. 1g), the test cue (neuron 2), the left–right turn direction (choice) (neuron 3) and the combination of the sample cue and test cue that indicates the reward direction (neuron 4). Note that the reward direction (combination of the sample and test cues) and choice are identical on correct trials and opposite on incorrect trials. We also identified neurons that were active only on one of the four trial types in both correct and incorrect trials, thus encoding multiple task variables (neuron 5; Fig. 1g).

Vine copula models to analyze encoding in multivariate neural and behavioral data

To quantify the selectivity of neurons for a task variable, we isolated the contribution of the variable to a neuron’s activity while controlling for other variables that also contribute. This was important because neural activity is modulated by movements of the mouse19,20,31, and a mouse’s movements correlate with task variables (Extended Data Fig. 2a,c). We considered the locomotor movements used to control the virtual environment.

We adapted nonparametric vine copula (NPvC) models to estimate the multivariate dependence among a neuron’s activity, task variables and movement variables (Fig. 2a). This method expresses the multivariate probability densities as the product of a copula, which quantifies the statistical dependencies among all these variables, and of the marginal distributions conditioned on time, task variables and movement variables32,33,34. The mutual information between two variables depends only on the copula and not on the marginal distributions35. Using a sequential probabilistic graphical model called the vine copula32,34, we broke down the complex, data-hungry estimation of the full multivariate dependencies into a sequence of simpler, data-robust bivariate dependencies that were estimated using a nonparametric kernel-based method35 (Fig. 2a). This approach takes into account correlations between all the variables in the multivariate probability, does not make assumptions about the form of the marginal distributions and their dependencies, and is able to capture nonlinear dependencies between variables, thus providing advantages over conventional methods such as generalized linear models (GLMs)24,36,37. By discounting collinearities between task and behavioral variables, this method isolates the contribution of individual variables and improves the estimation of information in neural activity (Extended Data Fig. 4). Using the NPvC, we estimated the expected activity of a neuron for any value of task and movement variables and at any time in the trial (Fig. 2b). The NPvC predicted frame-by-frame held-out neural activity better than a GLM (Fig. 2c)24,36,37.

a, Schematic of NPvC model of neural activity (r) as a function of time (t), a vector of movement variables (x) with components (\({x}_{1},\ldots ,{x}_{n})\) and task variable (c). Conditional vine copulas are built between neural activity and all the other variables for each task variable (c). Mixing the vine copula and marginal distributions gives the conditional density function of neural activity and other variables. The vine copula model can be used either to estimate the value of neural activity conditioned over all the other variables (which is the copula fit \({r}_{\mathrm{NPC}}\)) or to generate samples, or to estimate various conditional entropy and mutual information values. b, Deconvolved calcium activity of two example neurons (black) and the cross-validated predictions of the NPvC model (orange, dashed line) and GLM (pink, solid line). c, Cumulative distribution of FDE across neurons for the GLM and the NPvC model.

We used the NPvC model to estimate the mutual information that could be decoded from a neuron’s activity about each task variable at each time point. This was computed as the information between the actual value of the task variable and the one decoded from the posterior probabilities of task variables computed with the NPvC, conditioned on all other measured variables19,24. In simulations of neural activities modulated either linearly or nonlinearly by movement variables, the NPvC outperformed a GLM in fitting the data with nonlinear dependencies to movement variables (Extended Data Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note ‘Comparison of the performance of NPvC and GLM on simulated neural population data’). The NPvC and GLM both correctly estimated the information conveyed by individual neurons and the information from neuron pairs, conditioned upon movement variables, when the tuning to behavioral variables was linear. When the tuning was nonlinear, the GLM underestimated the neuronal information, whereas the NPvC performed well. Thus, the NPvC provides a more accurate estimate of information and is more robust to nonlinear tuning, consistent with its better fits to the data.

Preferential, but widespread, routing of information

While our focus is on population codes in projection pathways, we first established the information encoded in single neurons and whether that information is specialized in projection pathways. The PPC neurons contained information about each task variable, even after conditioning on the movement variables (Fig. 3a). Sample cue information was high in the sample, delay and test segments. Both sample cue and test cue information were appreciable in the early part of the test segment when the cues needed to be combined to inform a choice (Fig. 3a, left). The PPC neurons thus carried information about the reward direction (combination of the sample and test cues) and the choice, but the choice information was larger, indicating that PPC activity was more related to the turn direction selected by the mouse than the reward direction defined by the cues (Fig. 3a, middle). In addition, PPC neurons contained information about the mouse’s movements (Fig. 3a, right). Individual neurons contained relatively low information, likely due to transient activity patterns, trial-to-trial variability and multiplexing of information about different variables12,19,20,24,26.

a, Time course of different information components in all PPC neurons. Shading indicates mean ± s.e.m. b, Average single-neuron information in different populations about different task variables during the first 2 s after sample cue onset, delay onset or test cue onset. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. across cells. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, computed using two-sided t test with Holm–Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Nonlabeled, n = 2,506 cells; cPPC projection, n = 93 cells; RSC projection, n = 127 cells; ACC projection, n = 134 cells. rewdir, reward direction.

Information for the sensory-related task variables—sample cue, test cue and their combination that indicates the reward direction—was enriched in ACC-projecting neurons and lowest in contralateral PPC-projecting cells (Fig. 3b). Thus, PPC preferentially transmits sensory information to ACC. In contrast, information about the choice and movements was similar across the projection types, indicating that this information is more uniformly transmitted (Fig. 3b). All three projection types had lower information about the mouse’s movements than the unlabeled cells, suggesting that movement information is enriched in neurons projecting to areas not studied here (Fig. 3b, right). Cells projecting to contralateral PPC often had less information about each variable than the unlabeled cells, suggesting that across-hemisphere communication is less critical for encoding specific task and movement events. RSC-projecting neurons carried the sensory and choice information typical of the PPC population (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Therefore, neurons projecting to different targets differ in their encoding, revealing a specialized routing of signals. However, each projection contains significant information about each variable, showing that PPC also broadcasts its information widely. To understand population coding in projection pathways, we focused on choice information because it is the largest contributor to task-related variables.

Enriched IE pairwise interactions in neurons projecting to the same target

The structure of correlated activity patterns in populations of neurons can impact the transmission and reading out of information7,38. We computed pairwise noise correlations7,38, defined as the correlations in activity for a pair of neurons for a fixed trial type (Methods; Fig. 4a). We focused on the first 2 s after the test cue onset. Remarkably, noise correlations were significantly larger in pairs of neurons projecting to the same target than in unlabeled neurons with unidentified projection patterns, both for signed values (Fig. 4b, left, and Extended Data Fig. 5a) and absolute values (Extended Data Fig. 5b), suggesting that correlations are a key part of coding in output pathways. Noise correlations were higher on correct trials than on incorrect trials, consistent with the possibility that correlations are functionally relevant in guiding behavior25 (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 5a). We also considered that behavioral variability within a given trial type could contribute to trial-to-trial variability and thus potentially to noise correlations. After using the single-neuron NPvC models to compute partial correlations regressing out the effect of movement variability, noise correlations were lower, confirming that movement variability contributed to traditional noise correlation measures (Fig. 4b, right, and Extended Data Fig. 5a). Even in this case, noise correlations were higher in neurons projecting to the same target than in pairs of unlabeled neurons and higher in correct trials (Fig. 4b, right, and Extended Data Fig. 5a). These patterns of noise correlations were present even for pairs of neurons with similar separation in anatomical distance (Extended Data Fig. 5c).

a, Schematic of the models to compute pairwise joint probability density functions and conditional joint probability density functions of two neurons with correlated activities (\({r}_{1},{r}_{2}\)) as a function of time (t). A vector of movement variables (x) with components (\({x}_{1},\ldots ,{x}_{n})\) is represented. Using single-neuron NPvC model outputs, we build different types of pairwise correlation models with or without conditioning over the movement variables. The joint pairwise model is then used to estimate noise correlations or interaction information. b, Left: noise correlations computed for pairs of nonlabeled neurons and pairs of neurons projecting to the same area for correct and incorrect trials. Right: same except for noise correlations conditioned on movement variables. c, Similar to b but for interaction information. d, Average single-neuron choice information in different populations during the first 2 s after the test onset for correct and incorrect trials over all nonlabeled and projection cells. e, Histogram of interaction information divided into pairs of IE (red), IL (blue) and independent pairs (green). In b–d the average is computed over all the simultaneously recorded pairs of nonlabeled or same-target projection cells. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. across all pairs of neurons. *P < 0.05, and ***P < 0.001, t test with two-sided Holm–Bonferroni correction for statistical multiple comparisons. Nonlabeled, n = 145,439 pairs; same projection, n = 1,355 pairs.

Depending on the well-characterized relationships between signal and noise correlations, noise correlations can either reduce or enhance the information in neural populations7,38. To quantify how much a neuron pair’s noise correlations increase (IE) or decrease (information-limiting (IL)) information about a task variable, for each pair of neurons, we computed the interaction information (Fig. 4a). This was defined as the mutual information between the actual value of the task variable and the value decoded from the pair’s activity using NvPCs trained with noise correlations minus the information between the variable’s actual value and the value decoded from the pair’s activity using NvPCs trained blind to noise correlations. The former refers to the actual information carried by the pair, and the latter refers to independent information.

Interaction information was on average positive, and thus noise correlations were on average IE (Fig. 4c). Remarkably, interaction information on correct trials was larger in pairs of neurons projecting to the same area compared to pairs of unlabeled cells (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, interaction information was higher on correct trials than on incorrect trials. For pairs of neurons projecting to the same target, interaction information was even closer to zero on incorrect trials (Fig. 4c). In contrast, in single neurons, choice information was similar between correct and incorrect trials (Fig. 4d), suggesting a specific role of neuron–neuron interactions for generating correct behavioral choices. Similar results were obtained when comparing decoding performance (fraction correct) of NvPC decoders trained with or without correlations (Extended Data Fig. 5g). Therefore, pairwise interactions differ in populations projecting to the same target relative to surrounding neurons, enhance the information in an output pathway and may aid accurate decisions.

Interestingly, there was a wide range of interaction information values across pairs of neurons, with extended and almost symmetric tails for pairs of neurons with IE (significantly positive) and IL (significantly negative) interaction information (Fig. 4e and Extended Data Fig. 5f). Pairs of neurons for which the sign of signal correlations (that is, similarity of choice selectivity of the neurons) was the same as the sign of noise correlations had IL interactions, whereas pairs with opposite signs for signal and noise correlations had IE interactions38,39,40 (Extended Data Fig. 5k,l). For both IE and IL pairs, interaction information was higher in absolute value in correct trials compared to error trials, consistent with higher noise correlations resulting in greater levels of both types of interactions41 (Extended Data Fig. 5e). The IE interactions had higher magnitude interaction information in pairs of neurons with the same projection target compared to unlabeled pairs, whereas IL interactions had similar magnitudes of interaction information between same projection and unlabeled pairs (Extended Data Fig. 5e). Thus, PPC contains a rich mix of IE and IL pairs, with IE interactions having a preferential contribution to output pathways.

We also computed the interaction information for individual projection targets and the sample cue and test cue (Extended Data Fig. 5d). The RSC-projecting pairs had similar interaction information about the mouse’s choice compared to unlabeled pairs, consistent with RSC-projecting neurons being most like the unlabeled population. Test cue information had similar but weaker results to choice information. For sample cue information, interaction information was not different between cells projecting to the same target and unlabeled pairs. Thus, there exists a possible specificity of interactions between neurons with respect to different task variables and projection pathways.

The network structure of pairwise interactions

Two networks with the same set of IL and IE interactions can differ in how these interactions are organized within the network (Fig. 5a,b). For example, the same set of interaction pairs can be distributed either randomly (Fig. 5a, top) or structured as clusters containing enriched IE or IL interactions (Fig. 5a, middle and bottom).

a, Schematics of a random network (top), a network with clustered interactions (middle) and a network with modular structure (bottom). b, Sketch of how networks with the identical probability of IE and IL interactions can be organized randomly or in clusters of IE or IL pairs. Red and (+) indicate IE pairs. Blue and (−) indicate IL pairs. c, Relative triplet probability with respect to a random network for nonlabeled and same-target populations during correct (left) and incorrect (right) trials. The random network has the same distribution of pairwise interactions, except that they are shuffled between neurons. d, Global cluster coefficient of IE and IL subnetworks relative to a random network. e, Schematic of a two-pool network model. f, Schematic of the space of two-pool networks is quantified in terms of the probability of IE pairs in pool 1 (x axis) and pool 2 (y axis) minus the probability of these pairs in a random network. Red indicates IE pools and blue indicates IL pools. g, Schematic of some examples of symmetric and asymmetric networks corresponding to different points in the two-pool network space along the diagonal (red dashed line) or antidiagonal (blue dashed line) axes. h, Left: the probabilities of different triplets computed for different two-pool networks minus the triplet probabilities in a random network, computed analytically as derived in Supplementary Note ‘Analytical calculation of triplet probabilities in the two-pool model of network structure’ for two-pool networks. Right: the triplet probabilities for three example model networks sampled from the space of two-pool networks. i, At each point in the 2D space of two-pool networks, comparison of the triplet probabilities for the model network and the empirical data. The similarity index ranges from 1 for similar networks to 0 for completely different networks. Yellow circles correspond to networks that are more similar to data for nonlabeled (left) and same-target projection networks (right). The four dashed contours correspond to two-pool networks with similar value of each of the four triplet probabilities to the one obtained from data (from Fig. 5c for correct trials). j, Using pools of neurons defined based on their choice selectivity to left or right choices, the average interaction information within the pool and between the pools, relative to a random network. Pink indicates same-target projections. Black indicates nonlabeled neurons. Statistical tests are performed over all the pairs of neurons in each pool. k, Similar to j but for the probability of IE pairs within or between pools, relative to a random network. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m. estimated using bootstrapping. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, two-sided t test with Holm–Bonferroni correction for statistical multiple comparisons. Nonlabeled, n = 1,080,382 triplets; same projection, n = 30,204 triplets.

Graph-theoretic measures can identify structured arrangements of pairwise links in a network. The simplest motifs in a graph beyond pairs are interaction triplets42,43. A network with IL clusters has a larger number of ‘−,−,−’ triplets compared to a random network, and a network with IE clusters has more ‘+,+,+’ triplets compared to a random network, where ‘−’ and ‘+’ indicate IL and IE pairwise interaction links, respectively (Fig. 5a,b). For interactions of choice information, we computed the difference in the probabilities of ‘−,−,−’, ‘−,−,+’, ‘−,+,+’ and ‘+,+,+’ triplets between our data and an unstructured network obtained by randomly shuffling the position of pairwise interactions within the network, without changing the set of interaction values. In the unlabeled population, triplet probabilities were like those in a random network, indicating that the pairwise interactions are not structured (Fig. 5c). However, in populations of neurons projecting to the same target, there was an enrichment of ‘+,+,+’ and ‘−,−,+’ triplets and fewer ‘−,−,−’ and ‘−,+,+’ triplets compared to a random network. Notably, this structure was present only on correct trials and not when mice made incorrect choices (Fig. 5c). The network structure was present in ACC-projecting, RSC-projecting and contralateral PPC-projecting populations for choice information but was less apparent for sample cue and test cue information (Extended Data Fig. 6a,b).

We then used a graph global clustering coefficient42,43 to measure IL or IE clusters. This coefficient compares the frequency of specific triplets in real data to a shuffled network, measured as the ratio between the number of specific closed triplets and the number of all triplets, normalized to the same quantity computed from shuffled networks. On correct trials, the clustering coefficient obtained from data was larger compared to a shuffled network for IE interactions, meaning that these interactions were clustered. In contrast, for IL interactions, the clustering coefficient was smaller than for a shuffled network, indicating that they were set apart (Fig. 5d). This clustering was not found in unlabeled neurons and when mice made incorrect choices (Fig. 5d). Thus, pairwise interactions are clustered in the network of neurons projecting to the same target.

To exemplify how the network’s topology relates to the triplet distributions, we considered a simple two-pool model in which the network structure can be varied parametrically, while keeping the overall set of values for IE and IL interactions constant (Fig. 5e). Each pool was parameterized by the difference in probability of IE pairwise interactions within the pool relative to a random network. Thus, the range of possible network models resides in a two-dimensional (2D) space consisting of the enrichment of IE interactions in pool 1 along one axis and in pool 2 along the second axis (Fig. 5f). The diagonal corresponds to symmetric networks, in which both pools have more IE or more IL interactions than a random network. The antidiagonal corresponds to asymmetric networks, where one pool has more IE interactions and the other has more IL interactions. Networks near the origin are like a random network.

For every point in the 2D space of network models, we analytically computed the triplet probabilities compared to a random network and then mapped the triplet probabilities estimated in our data to the parametric model (Fig. 5h, left, and 5i). Populations of cells projecting to the same target mapped to a symmetric network with both pools having enriched within-pool IE interactions and elevated across-pool IL interactions (Fig. 5i, right). In contrast, the population of unlabeled neurons mapped closely to the origin, corresponding to a randomly structured network (Fig. 5i, left).

This network structure was present in pools of neurons defined by their choice selectivity. For unlabeled neurons, the interaction information and proportion of IE interactions were similar to those of a random network, both within pools of neurons with similar choice preferences and across pools with different preferences (Fig. 5j,k). In contrast, for neurons with the same projection target, pools of cells with the same choice preference had higher interaction information and a larger proportion of IE interactions than the random network (Fig. 5j,k). Furthermore, in these same-target projection populations, cell pairs with opposite choice preferences had lower interaction information and an enrichment of IL interactions. This structure was strong on correct trials and largely absent when mice made incorrect choices.

Together, these results reveal rich structure in the pairwise interaction information that is approximated by a network of symmetric pools with enriched within-pool IE interactions and across-pool IL interactions. Notably, this structure was only present in neurons projecting to the same target, not in neighboring unlabeled neurons, and only when mice made correct choices. This finding could support the propagation of information to downstream targets, leading to accurate behavior.

The contribution of the network structure of pairwise interactions to population information

To test how the network-level structure of pairwise interactions affects the information encoded in a neural population11, we analytically expanded the information encoded by the population about a given task variable as a sum of contributions of interaction graph motifs—nodes (single-neuron information), links (pairwise interaction information) and triplets (triplet-wise arrangements of pairwise interaction information; Fig. 6b). We illustrate this expansion for the case of a symmetric network with the assumption that single-pair information is small compared to single-neuron information, which describes our data well (Fig. 6b–d). For calculating information, we used an expansion of population information that is also valid for nonsymmetric networks (Extended Data Fig. 8d and Supplementary Note ‘Analytical expansion of the population information’).

a, Schematic of how the population information can be decomposed into the following three components: independent information, unstructured interaction information and structured interaction information. b, The population information can be expanded as a sum of contributions from network motifs with increasing complexity. For a symmetric network, the dominant contributions are from single neurons, interaction pairs and interaction triplets. c, In symmetric networks, triplets contribute to structured interaction information with a positive or negative sign if they have an even or odd number of IL interactions, respectively. d, Structured interaction information in the space of symmetric two-pool networks. The structured interaction information can be IE or IL, depending on whether the pools have enriched IE or IL pairs. Pink and black points correspond to the networks of same-target projection and nonlabeled neurons, respectively. e, Independent, unstructured interaction and structured interaction information for nonlabeled (black) and same-target projection (pink) neurons during correct and incorrect trials for increasing population size. Shading indicates mean ± s.e.m. estimated from bootstrapping the information values are computed using the analytical terms presented in Supplementary Note ‘Analytical calculation of triplet probabilities in the two-pool model of network structure’. ***P < 0.001, between nonlabeled and same-target projection neurons in correct trials, two-sided t test with Holm–Bonferroni correction for statistical multiple comparisons at n = 75 population size. Nonlabeled, n = 1,080,382 triplets; same projection, n = 30,204 triplets.

We broke down the population’s total information about a task variable into three components (Fig. 6a). The independent information is the information if the population had the same single-neuron properties but zero pairwise noise correlations7,39,44,45. The interaction information, which is the difference between the total population information and the independent information, was divided into two components. The unstructured interaction information is the information in a population with the same values of pairwise interactions as the data, but randomly rearranged across neurons by shuffling (no network structure), minus the independent information. This component quantifies the contribution of pairwise interactions to the population information. The structured interaction information is defined as the difference between the total population information and the population information in an unstructured network (Fig. 6a). This component isolates the contribution of the structure of pairwise interactions within the network.

The structured interaction information depends on the triplet-wise arrangements of pairwise interaction information. Based on analytic calculations, each triplet contributes to the structured interaction information with a sign that depends on the product of the signs of its pairwise interactions (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Note ‘Relating structured interaction information and triplet probabilities’). There is a positive contribution for {‘+,+,+’, ‘−,−,+’} triplets and a negative contribution for {‘−,−,−’, ‘−,+,+’} triplets. The sign of the structured interaction information, therefore, depends on the difference in the probability of triplets relative to a shuffled network lacking structure. The magnitude of the structured interaction information depends on these triplet probabilities as well as on the single-neuron information and pairwise interaction values within the triplets.

To visualize how structured interaction information changes with the topology of the network, we computed the value of the structured interaction information in the simple two-pool network defined in ‘The network structure of pairwise interactions’, making the additional assumption that the values of single-neuron information and the absolute values of interaction information of each triplet are homogeneous across the network (Fig. 6d). Symmetric networks with enriched IE pools (compared to a randomly structured network) have structured interaction information that is IE, whereas symmetric networks with enriched IL pools have negative structured interaction information (Fig. 6d).

Using the single-neuron information, pairwise interactions and triplet probabilities estimated from our data, we computed the independent, the unstructured interaction and the structured interaction components of the population information for choice (for a symmetric network (Fig. 6e) and for a nonsymmetric network (Extended Data Fig. 8d)). The independent information was the largest component and was similar between neurons projecting to the same-target and unlabeled populations (Fig. 6e, left). The unstructured and structured interaction information contributed less to population information, as expected, because pairwise interaction information values were smaller than single-neuron information values (Fig. 4c,d). Strikingly, the contributions of both structured and unstructured interaction information were markedly larger for neurons projecting to the same target than for unlabeled neurons (Fig. 6e, middle and right). The larger unstructured interaction information for populations projecting to the same target is a consequence of their higher pairwise interaction values. The higher structured interaction information for populations projecting to the same target is instead a consequence of their network structure (Extended Data Fig. 8e). The structured interaction information contributed close to zero in the unlabeled population, consistent with the lack of network structure in this population. The structured interaction information in the cells projecting to the same target was positive and IE, consistent with this population having a symmetric network structure with enriched within-pool IE interactions and across-pool IL interactions compared to a randomly structured network.

Notably, both mathematical calculations (Extended Data Fig. 10 and Supplementary Note ‘Analytical expansion of the population information’) and numerical evaluations (Fig. 6e) show that the contribution of structured interaction information scales faster with increasing population size than the two other components (Fig. 6e). Also, the structured interaction information was mostly absent on incorrect trials, whereas independent information was largely unchanged, suggesting that the structure of network interactions may carry information to guide accurate behavior. We compared the size of the structured interaction information to the information needed for behavioral choices. On correct trials for a population of 75 cells, the 0.015 bits carried by the structured interaction information (Fig. 6e) contribute 1.5% of the information needed to always make a correct choice (1 bit) and 5% of the information needed to perform as well as the mouse (~80% correct performance corresponds to ~0.3 bits of mutual information between the rewarded choice and the mouse’s choice; dashed line in Extended Data Fig. 1a). Based on this and the supra-linear scaling with population size, the structured interaction information in a population of a few hundred cells is expected to contribute a sizeable fraction of the total information needed to make correct choices.

We found similar trends for network structure for choice information for populations of neurons projecting to contralateral PPC, RSC and ACC (Extended Data Fig. 7c). Consistent with differences in triplet probabilities for sample cue and test cue information with respect to the choice information (Extended Data Fig. 6a), the network information was either IE or IL when computed for sample cue or test cue information (Extended Data Fig. 7b), suggesting the specificity of network structure with respect to the information content.

Together, these results reveal a rich network structure in the pairwise interactions within a population that strikingly enhances information levels and is only present in cells projecting to the same target and when mice make correct choices. Thus, populations of PPC cells projecting to the same target are organized in a specialized manner to enhance the propagation of information to downstream targets, potentially aiding accurate decision-making.

Discussion

The understanding of population codes has been built on studies of coding in populations of all neurons recorded from a given location, likely including neurons projecting to different target areas and thus mixing neurons that are read out by different downstream networks. Instead, by studying population codes in neurons that project to the same target area, we discovered that neurons comprising an output pathway in PPC form specialized population codes.

A first specialized feature is an elevated strength of pairwise correlations. Both IL and IE correlations are higher when mice make correct choices relative to incorrect ones, suggesting that they both have functional relevance. The enrichment of IE correlations in neurons projecting to the same target, compared to unlabeled neighboring neurons, suggests that these interactions aid the transmission of information between areas. On the other hand, IL correlations may support accurate behavior by increasing the efficacy and robustness of information transmission24,25,46. However, because IL correlations are similar in neurons projecting to the same target and neighboring cells, they may be of general utility and not specialized to communication across areas.

A second specialized feature is a network-level structure of pairwise interactions that enhances the population’s information about the mouse’s choice. This enhancement arises from a diverse mix of IE and IL pairwise interactions. While the information provided by the network structure is small relative to that of single neurons in small populations, we estimate that it grows rapidly with population size and provides a substantial fraction of the information carried by the whole population projecting to a specific area. In addition, the network-level structure is present only when mice make correct choices, is absent when mice make incorrect choices and is not apparent in populations of neighboring neurons. Thus, the enhanced information encoding carried by this structure may be key to correct behavior and specialized for information transmission between areas. Future work should investigate whether structured synaptic connections between cells within the same output pathways contribute to this network structure11,47.

We established a framework to link network-level structures to their effect on population codes. Extending this formalism, possibly with tools to identify interacting populations across areas2,48,49, may allow studies of how the network structure of information encoding within a ‘sending’ area affects transmission to downstream areas. For example, specific triplets, such as ‘−,−,+’ triplets, may be particularly useful for information transmission because they enhance information while containing IL correlations11. Previous work has focused on how pairwise and higher-order correlations shape the information encoded in a population7,38,41,50,51,52,53, without considering how these interactions are arranged as a network. Recent empirical work has identified network structures in visual cortex8, and theoretical studies indicate how network structures may impact the encoding of information7,11. Our results contribute by demonstrating how structured interactions in populations comprising an output pathway enhance information encoding.

We developed NPvC models that more effectively discount covariations between task and movement variables and thus better estimate the relationships between variables in a large multivariate setting, compared to simpler models19,20,31,54 (Extended Data Fig. 4). If covariations between task and movement variables are not accurately accounted for, dependencies across variables can mask underlying IE and IL interactions and prevent discovering network structures (Extended Data Fig. 4e,f). In simulations, the NPvC had more accurate single-cell information estimates compared to a GLM when the modulation by behavioral variables is nonlinear (Extended Data Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note ‘Comparison of the performance of NPvC and GLM on simulated neural population data’). Moreover, when the modulation is nonlinear, the NPvC better estimates the interaction information because undiscounted effects of cotuning to behavioral variables generate artificial redundancy. Consequently, the NPvC provides a better estimate of the distribution of pairwise interactions within the network compared to a GLM. In our empirical data, the NPvC fit the neural activity better than the GLM. For single-neuron information, a GLM reproduced the overall distribution of single-neuron information across task variables and projection targets, although with reduced values (Extended Data Fig. 9a). The GLM showed positive, although reduced, interaction information in correct trials, with the reduced values arising because of redundancy overestimation (Extended Data Fig. 9c). However, the GLM did not reveal a network structure of the interactions (Extended Data Fig. 9d). Therefore, NPvC models are beneficial for understanding information in large populations and complex behavioral settings.

While PPC broadcasts information about all task variables to ACC, RSC and contralateral PPC, we observed some specificity in the types of information transmitted in these pathways. Sensory-related information was strongest in ACC-projecting neurons, consistent with sensory and motor communication pathways between parietal and frontal cortices55. In contrast, contralateral PPC projections carried less information about the task, implying that cross-hemisphere interactions serve a role other than computing specific task quantities and may instead help maintain activity patterns56. All three intracortical projection pathways had lower information about the mouse’s movements, indicating that cells projecting to other targets, perhaps subcortical areas, might be more related to the biasing of movements57. Collectively, these findings both support the notion of specificity in the information flow in cortex58,59,60,61 and fit with findings of highly distributed representations across cortex and work that has failed to identify categories of neurons in PPC based on activity profiles19,20,22,30,31,61,62,63.

Together, our findings demonstrate that specialized network interaction structures in PPC facilitate the transmission of choice signals to downstream areas and that these structures may be important for guiding accurate behavior. Our results suggest that the organization principles of neural population codes can be better understood in terms of optimizing transmission of encoded information to target projection areas rather than in terms of encoding information locally.

Methods

Mice

All experimental procedures were approved by the Harvard Medical School Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were performed in compliance with the Guide for Animal Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Imaging data were collected from ten male C57BL/6J mice that were 8 weeks old at the initiation of behavior task training (stock 000664, Jackson Labs).

Virtual reality system

The virtual reality system has been described previously26. Head-restrained mice ran on an 8-inch diameter spherical treadmill. A PicoP micro-projector was used to back-project the virtual world onto a half-cylindrical screen with a diameter of 24 inches. Forward/backward translation was controlled by treadmill changes in pitch (relative to the mouse’s body), and rotation in the virtual environment (virtual heading direction) was controlled by the treadmill roll (relative to the mouse’s body). Movements of the treadmill were detected by an optical sensor positioned beneath the air-supported treadmill. Mazes were constructed using VirMEn in MATLAB64.

Behavioral training

Before behavioral training, surgery was performed in 8-week-old mice to attach a titanium headplate to the skull using dental cement. At least 1 day after implantation, mice began a water schedule, receiving at least 1 ml of water per day. Body weights were monitored daily to ensure they were greater than 80% of the original weight. Mice were trained to perform the delayed match-to-sample task using a series of progressively complex mazes. Mice were rewarded with 4 μl of water on correct trials. First, naive mice were trained to run down a straight, virtual corridor of increasing length to obtain water rewards. In the second stage, mice learned to run in a T-shaped maze, making a choice between the left and right arms. The correct choice arm was signaled by the presence of a tall tower at the choice arm. After the mice were able to run straight on the ball and make turns, we trained the mice on stage 3, where we began to familiarize them with running into the choice arm that matched the color presented in the maze stem (sample cue). The walls of the stem were either black or white (sample cue; randomly selected from trial to trial). The left and right choice T-arms were black and white, respectively, or vice versa (test cue). At this stage of training, the correct choice arm was signaled both by a tall tower in the correct arm and by the T-arm that matched the color of the sample cue. Notably, at this stage, the mouse can still perform accurately even if it ignores the sample and test cues, as it can simply run to the choice arm with the tower. In the fourth stage, the maze was the same, except that we added a tower to the unrewarded choice arm as well. In this stage, the mouse cannot simply run to whichever arm has a tower (because both arms have towers) and must run into the arm that matches the color of the sample cue. In stage 4, the maze was exactly like the previous one, except the choice arms and towers (test cue) appeared gray as the mouse ran down the maze. The colors of the choice arms and towers (test cue) were not revealed until the mouse reached three-fourths of the way down the stem. When the black and white choice arms were revealed, the mouse could begin to plan and execute a turn left or right. In the final stage, we begin training toward the final implementation of the delayed match-to-sample task. We introduced a delay segment by making the walls of the T-stem gray at the end of the stem and gradually increasing the length of the stem that is gray (delay segment). The mouse received its first trials of the delayed match-to-sample task when at least the entire last one-fourth of the stem walls were gray. In such trials, when the mouse’s position reached three-fourths of the way down the stem, there was a short moment in which both the stem walls and the choice arms were gray. At this point, the mouse must rely on its memory of the initial sample cue walls to make the correct turn. We gradually increased the length of the gray segment until the mouse performed with over 85% accuracy, with a delay averaging at least 2 s in duration. The entire training program was completed in 12–18 weeks.

Surgery

When mice reliably performed the delayed match-to-sample task, the cranial window implant surgery was performed. Mice were given free access to water for 2 days before surgery. During the surgery, mice were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane and the headplate was removed. Craniotomies were performed over PPC centered at 2 mm posterior and 1.75 mm lateral to bregma. GCaMP6 was injected at three locations spaced 200 μm apart at the center of the PPC. A micromanipulator (MP285, Sutter) was used to position a glass pipette approximately 250 μm below the dura, and a volume of approximately 50 nl was pressure-injected over 5–10 min. Dental cement sealed a glass coverslip on the craniotomy, and a new headplate was implanted, along with a ring, to interface with a black rubber objective collar to block light from the VR system during imaging. Craniotomies were also performed over the contralateral PPC (2 mm posterior and 1.75 mm lateral to bregma) and ACC (1.34 mm anterior and 0.38 mm lateral to bregma, and 1.3 mm ventral to the surface of the dura). More than 200 nl of retrograde tracer (CTB-Alexa647, CTB-Alexa405 or red retrobeads) were injected at each site. The retrograde tracer injection into RSC was made through the craniotomy for PPC imaging, targeting the most medial portion of the craniotomy (~0.5 mm lateral from the midline). Craniotomies for the retrograde tracers were sealed with KwikSil (World Precision Instruments). Mice recovered in 2–3 days after surgery and then resumed their water schedule. Imaging was performed nearly daily in each mouse, starting 2 weeks after surgery, and continued for 1–2 weeks.

Obtaining anatomical stacks

Anatomical stacks of cells double-labeled with GCaMP and retrograde tracers were acquired using a two-photon microscope, taken at 2-μm intervals from the surface of the dura to approximately 300 μm below the surface. For images of cells double-labeled with GCaMP and CTB-Alexa647, we used a dichroic mirror (562-nm long pass, Semrock) and bandpass filters (525/50 nm and 675/67 nm, Semrock) and delivered the excitation light at 820 nm to visualize both GCaMP and the Alexa fluorophore simultaneously. We also took images of GCaMP and CTB-Alexa405 using a dichroic mirror (484-nm long pass) and bandpass filters (525/50 nm and 435/40 nm) and delivered excitation light at 800 nm. Finally, we took images of GCaMP and red retrobeads with dichroic mirror (562-nm long pass) and bandpass filters (525/50 nm and 609/57 nm) and delivered excitation light at 820 nm. These anatomical stacks enabled us to visually identify cells as either double-labeled with GCaMP and retrograde tracer or GCaMP-expressing and unlabeled with retrograde tracer. We then matched these GCaMP-expressing neurons from the anatomical stacks with the same GCaMP-expressing neurons during functional imaging, which was performed at 920 nm and during behavior. In some sessions, we took z-stacks immediately before functional imaging to ensure that some labeled cells were present in the field of view.

GCaMP imaging during behavior

For functional imaging, five mice were imaged using a Sutter MOM at 15.6 Hz at 256 × 64-pixel resolution (~250 × 100 μm) through a ×40 magnification water immersion lens (Olympus, NA 0.8). Five other mice were imaged using a custom-built two-photon microscope with a resonant scanning mirror (at 30-Hz frame rate) with a ×16 objective. ScanImage was used to control the microscope. Imaging sessions lasted 45–60 min. Each session was imaged over multiple 10-min acquisitions separated by 1 min, allowing any amount of GCaMP bleaching to recover. The imaging frame clock and an iteration counter in VirMEn were recorded to synchronize imaging and behavioral data.

Data processing

Custom-written MATLAB software was designed for motion correction, definition of putative cell bodies and extraction of fluorescence traces (dF/F). Fluorescence traces were deconvolved to estimate the relative spike rate in each imaging frame, and all analyses were performed on the estimated relative spike rate to reduce the effects of GCaMP signal decay kinetics.

To estimate the neural activity of individual cells from the calcium imaging data, we processed the data by the following steps: (1) motion correction—motion artifacts in the imaging data were corrected in each imaging frame. First, ‘line-shift correction’ was performed to align for line-by-line alternating offsets in images due to bidirectional scanning. Then, ‘sample movement correction’ was performed to remove between-frame rigid movement artifacts by FFT-based 2D cross-correlation65 and within-frame nonrigid movement artefacts by the Lucas–Kanade method66. (2) Cell selection—the spatial footprint of a putative cell was identified based on the correlation of fluorescence time series between nearby pixels. The correlation of fluorescence time series was calculated for each pair of pixels within a ~60 × 60-μm square neighborhood. Then, putative cells were identified by applying a continuous-valued, eigenvector-based approximation of the normalized cuts objective to the correlation matrix, followed by discrete segmentation with k-means clustering, which generated binary masks for all putative cells. (3) dF/F calculation—the magnitude of calcium transients was estimated by subtracting the background fluorescence from the raw fluorescence of a putative cell. For each putative cell, the background fluorescence of local neuropil was estimated by the average fluorescence of pixels that did not contain putative cells. Then, the neuropil fluorescence time series was scaled to fit the raw fluorescence of a putative cell by iteratively reweighted least-squares (robustfit.m in MATLAB) and was subtracted from the raw fluorescence to yield neuropil-subtracted fluorescence (Fsub). Then, dF/F was calculated as \(({F}_{{\rm{sub}}}-{F}_{{\rm{baseline}}})/{F}_{{\rm{baseline}}}\), where \({F}_{{\rm{baseline}}}\) was a linear fit of \({F}_{{\rm{sub}}}\) using iteratively reweighted least-squares (robustfit.m in MATLAB). The codes used in steps 1–3 are available at https://github.com/HarveyLab/Acquisition2P_class.git. (4) Deconvolution—the timing of spike events that led to calcium transients was estimated by deconvolution of fluorescence transients. dF/F was deconvolved by OASIS AR1 (ref. 67), which models the fluorescence of each calcium transient as a spike increase followed by an exponential decay, whose decay constant was fitted to each cell. The deconvolved fluorescence resulted in spikes that were sparse in time and varied in magnitude. The deconvolved fluorescence was used as a neural activity for the majority of the analyses.

NPvC models of single-neuron activity

To quantify the information carried by a neuron’s activity about task variables, while discounting possible contributions from movement variables, we built a multivariate probabilistic model of the activity of each neuron, time, behavioral variables (running velocity and acceleration) and task variables (schematized in Fig. 2c). We built this model using NPvC. We chose vine copulas because they allow constructing arbitrarily complex multivariate relationships (including relationships between non-neural variables, for example, relationships between trial types and behavioral variables) by combining bivariate relationships, which can be sampled accurately and robustly from a finite number of trials regardless of the details of the marginal distributions. We chose nonparametric estimators because the form of these relationships is not known a priori and we wanted to avoid biases originating from inaccurate assumptions. Here we describe the details of computing our nonparametric vine copula model, specifically for determining the probability density function of neural population activity given behavioral and task variables at each time point in the trial (Fig. 2b) and for assessing its goodness of fit (Fig. 2c).

We used vine copulas to estimate the conditional joint probability density function \(f\left(\bf{x}|\varGamma \right)\) for a set of variables \(\bf{x}=\{r,t,\bf{B}\}\), which, in our case, consists of the activity of a neuron \({x}_{1}\equiv r\), time \({x}_{2}\equiv t\) and the 5D vector \(\bf{B}\) of the five behavioral variables that we measured (virtual heading direction, lateral and forward running velocities, and lateral and forward accelerations), for each trial type Γ. Each trial type Γ (Γ =1 … 8) is defined by the sample cue, the test cue and trial outcome (correct or incorrect). Thus, there are four trial types for trials with correct choices and four trial types for trials with incorrect choices. Using the copula decomposition, the probability density function for each trial type Γ is represented as a product of the single-variable marginal probability density functions \(f\left({x}_{i}|\varGamma \right)\), and the copula \(c(\bf{x}|\varGamma)\), which captures the dependencies between all the variables, as follows:

We used a kernel density estimator68 to compute the single-variable marginal probability densities and a nonparametric c-vine copula to estimate the copula, representing the correlation structure between variables. We used a c-vine graphical model with neuron activity as the central variable. The probability density function of a c-vine can be expressed as the product of a sequence of nonparametric bivariate copulas32,69 (Supplementary Note ‘Vine copula modeling of neural responses’). We used similar order for the variables in the c-vine graphical model as \(\bf{x}=\{r,t,\bf{B}\}\) introduced above. Furthermore, we simplified the vine copula structure by considering the decomposition of the copula as a product of a time-dependent and a time-independent component \(c\left(\bf{x}|\varGamma \right)=c\left(r,t|\varGamma \right)c(r,\bf{B}|\varGamma )\), meaning that we assumed the tuning of neurons to movement variables is time independent. The sequence of bivariate copulas shaping the vine copula was then fitted to the data using a sequential kernel-based local likelihood process (Supplementary Note ‘Nonparametric pairwise copula estimation’)35. For each of the bivariate copulas, the kernel bandwidth was fitted to maximize the local likelihood obtained using a fivefold cross-validation method35. Using the estimated bandwidths for each copula in the vine sequence, we computed the multivariate copula density function of data points using a fivefold cross-validation process. We first used the training set to estimate the copula density on a 50 by 50 grid (Supplementary Note ‘Nonparametric pairwise copula estimation’) and then used the copula estimated on the grid point to interpolate the copula density on the test set. A similar procedure was followed to estimate cross-validated marginal density functions for each single variable. The conditional probability of neural responses in each trial condition and for each value of behavioral variables is computed using \(f(r|t,\bf{B},\varGamma )=\frac{f\,(r,t,\bf{B}|\varGamma )}{f\,(t,\bf{B}|\varGamma )}\), where, to compute the density function \(f(t,\bf{B}|\varGamma )\), we marginalized by integrating over the neuron response

In equation (2), we approximated the integration as a sum over a set of n = 200 points \({\{r}_{i}\}\) ranging linearly between the minimum (\({r}_{\min }\)) and maximum (\({r}_{\max }\)) value of the neural response within the session and \(\delta r=\frac{{r}_{\max }-{r}_{\min }}{n}\). By computing the density function \(f(t,\ldots ,\bf{B}|\varGamma )\) by marginalization of \(f(r,t,\bf{B}|\varGamma ),\) instead of fitting a new vine model between (\(t,\bf{B}\)) variables, any difference between these two density functions is only related to the dependency of the neural activity to other variables and not to a difference between how dependencies between (\(t,\bf{B}\)) variables are being quantified in the two models because of the fitting differences.

For each time point, we computed a copula fit of the activity of each neuron (indicated as NPvC fit in Fig. 2b) as a point \({r}_{\mathrm{cop}}\in {\{r}_{i}\}\) with the largest log likelihood given the considered trial type and the values of behavioral variables at the considered time point:

GLMs of single-neuron activity

We also fit a GLM model to compare it with the copula. We thus used a GLM with Poisson noise, a logarithmic link function and an elastic-net regularization24,27,36. We also used task variables defining the trial type, consisting of sample cue, test cue, choice and all their interactions (each binary task variable was coded as −1 or +1) together with the same behavioral variables we used in copula modeling as the predictors. Time-dependency during the task for single neurons was expanded using a raised cosine basis27 as follows:

For task variables, the cosine basis function has a width of 1 s, and the value at the center peak was either positive (\(W=+1\)) or negative (\(W=-1\)) depending on the identity of each task variable. The center peaks \({t}_{c}\) were spaced with a 0.5-s interval to tile the epoch with a half-width overlap. For selectivity to movements of the mouse, we first z scored each movement variable as \({z}_{i}\) and used a similar cosine basis as follows:

We considered 13 center peaks \({z}_{c}\) ranging from −3 to 3 with spacing of 0.5 for the cosine basis of movement variables.

Computation of neural data fitting performance of NPvC and GLMs

The performance of both the NPvC and the GLM in fitting single-trial single-neuron activity was evaluated by computing the fraction of the deviance explained (FDE) on the test data, defined as follows70:

where \({L}_{\rm{model}}\), \({L}_{\rm{null}}\) and \({L}_{\rm{sat}}\) are the likelihoods of observing the test data for the considered model (copula or GLM), the null model or saturated model, respectively, and are always computed for all the time points in all trials in a cross-validated fashion. For the GLM, the null model is a model that does not have any predictors, and its prediction of activity at any time point is the time-averaged rate of the neuron. For the copula null model, we defined a model of neural response that excluded all predictors from the trial, quantifying the proportion of neural activity that can be explained without knowledge of the time and movement variables used in the vine copula model. The likelihood is then computed using the marginal distribution of neural activity \({L}_{\mathrm{null}}=\log [f({r}_{\mathrm{data}})]\). The saturated model is the generative model in which the prediction exactly matches the observed activity at each time point in the test data. For the GLM, these values were computed using the analytical form of the GLM output at each time point using the logarithmic link function. For the copula model, which is nonparametric, the vine copula model is used to compute the likelihood for each neural activity \({L}_{\mathrm{model}}=\log [f({r}_{\mathrm{data}}|t,{\bf{B}},\varGamma )]\) as the model likelihood, where \({r}_{{\rm{data}}}\) is the real single-trial neural activity at time t from data. To compute the saturated likelihood, we considered the fact that the model prediction is derived from equation (3) and the saturated likelihood was considered to be the peak likelihood obtained \({L}_{\mathrm{sat}}=\max (\log [f({r}_{i}|t,\bf{B},\varGamma )])\), where \(\{{r}_{i}\}\) is the set of n = 200 grid points on the neural activity described before ranging from the minimum to maximum possible neural activity of each neuron. Each of the likelihood values on the data were computed using a fivefold cross-validation by fitting the NPvC on the training folds and estimating it on the test fold. The density function is estimated over a grid using the training set, and the grid is used to compute the density function over the test set (Supplementary Note ‘Nonparametric pairwise copula estimation’). We considered five different task epochs and fitted the model to each of them. The periods were from 0.5 s before to 2 s after the sample cue onset, delay onset, test cue onset, start of the turn and reward onset. We used only sessions that had at least five trials of each of the eight trial types.

Estimation of mutual information for single neurons

We used probabilities estimated from the vine copula approach, explained in ‘NPvC models of single-neuron activity’, to estimate single-neuron mutual information values (Fig. 3). To compute the mutual information between a group of variables (including neural activity and/or behavioral variables) and a task variable, we used a decoding approach and then computed information in the confusion matrix71,72,73. Here a task variable (c) was a binary variable taking a value c of +1 or −1 to indicate one of the two possible values of either sample cue, test cue, reward location or choice direction. For each task variable, we decoded its value in each trial using the copula model to compute (through Bayes’ rule) the posterior probability of the task variable given the observation in the same trial of a set of variables \(\bf{z}\), which could be the full set \(\bf{x}=\{r,t,\bf{B}\}\) (Extended Data Fig. 2b). or a subset of it. This posterior probability of c can be obtained from the copula model as follows:

where the sum is over all the trial types \(\varGamma\) (corresponding to the combinations of two sample cues, two test cues and two trial outcomes (correct or incorrect) and consists of eight possible values when using all trials and four values when using either correct or incorrect trials), which have value c for the considered task variable. For example, considering analyses limited to correct or incorrect trials, the sum will be over the four correct or incorrect trial types. Considering analyses using all the trials, the sum will be over all eight trial types. Considering sample cue correct trials only, the sum in equation (6) will be over the two trial types with correct outcome and two sample cues, and so on. \(P\left(\varGamma \right)\) is the probability of occurrence of trial type Γ across all considered trials. In the above equation, the probability density of the variable \(\bf{z}\) given the trial type Γ, \(f\left(\bf{z}|\varGamma \right)\), is computed using the copula model by using equation (1) when \(\bf{z}=\{r,t,{\bf{B}}\}\) or using equation (2) when \(\bf{z}=\{t,\bf{B}\}\).

We then used the posterior probabilities to decode the most likely task variable given the variables \(\bf{z}\) observed in the considered trial:

The information about the task variable decoded from neural activity was then computed as the mutual information between the real value C of the variable and the one \(\hat{C}\) decoded from neural activity, as follows:

where \(P\left(c,\hat{c}\right)\) is the confusion matrix, that is, the probability that the true value of the task variable is c and the value of the decoded one is \(\hat{c}\), and \(P\left(c\right)\) and \(P\left(\hat{c}\right)\) are the marginal probabilities. We also computed the NVpC decoder’s performance as fraction of correct decoding, obtaining similar results (Extended Data Fig. 3f).

To compute the information \(I(r{;}C{|}t,\bf{B})\) between the task variable and the neural activity at a given time point, conditioned over the behavioral variables, we used the following equation for conditional mutual information:

In the above equation, \(I(r,t,\bf{B}{;}C)\) was computed after decoding \(\hat{C}\) using the copula derived from equation (1) where \(\bf{z}=\{r,t,\bf{B}\}\), and \(I(t,\bf{B}{;}C)\) was computed after decoding \(\hat{C}\) using the copula constricted with equation (2) where \(\bf{z}=\{t,\bf{B}\}\).

We computed the mutual information \(I(r{;}\bf{B}{|}t)\) between the neural activity and the behavioral variables \(\bf{B}\) at time \(t\) (used in Fig. 3a,b) using Shannon’s mutual information formula with probabilities defined by the copula \(f(r|t,\bf{B},\varGamma )\), the marginalized copula \(f\left(r|t,\varGamma \right)\) and the probability \(P\left(\varGamma \right)\) of each trial type Γ as follows:

The entropies \(H(r|t,\bf{B},\varGamma )\) and \(H\left(r|t,\varGamma \right)\) were computed by averaging the corresponding NPvC estimated log-likelihoods at the neural activity and movement values sampled from the trial type Γ at each time point.

For the information about the task variables, we chose a computation of information from the decoding matrix, similar to the details in, for example, ref. 24, because when computing neural population information about categorical values, this computation is robust and has a lower variance and bias than a direct computation from the probabilities. The reason is that the decoding step compresses the dimensionality of the neural responses from which the information is computed, especially when considering neuron pair responses and interaction information. This computational robustness was useful because we wanted to use the information values for each neuron pair regarding task variables at both the single-neuron and single-pair levels. For the information computed about the behavioral variables, it was not useful to perform decoding and confusion matrix computations, as the space of behavioral variables was larger than that of neuronal activity. Therefore, we used a direct calculation of information through the Shannon formula based on the response probabilities. To correct for the limited sampling bias in the information estimation, we computed a shuffled information distribution by repeating the same process after shuffling the label for the trial type (for trial type information, see equation (9)) or the neural activity (for the equation (10) information) 1,000 times and subtracted the mean of the shuffled distribution from the estimated mutual information to correct for the bias74 (Extended Data Fig. 2c).

To compare the magnitude of information values computed from neurons and neuronal populations to the information values needed to achieve mouse’s behavioral performance, we generated a set of simulations to convert task performance values (defined as the fraction of trials for which the mouse choice was rewarded) into its corresponding mutual information values (defined as the mutual information between rewarded choice and mouse’s choices in all trials). This relationship is reported as the left and right y-axis values in Extended Data Fig. 1a. To generate this relationship, we considered n trials (we used \(n=200\) in results reported in Extended Data Fig. 1a as this was similar to the range of trial numbers in real experimental data) of equal numbers of left or right rewarded directions (represented by a vector C). Then, for various mouse performance values P (we considered 200 equally spaced performance values between 0.65 and 1), we generated a corresponding mouse’s choice vector (represented by a vector \(\hat{{\bf{C}}}\)) with a fraction \(P\) of correct decisions. We then computed the empirical confusion matrix \(P\left({\bf{C}},\hat{{\bf{C}}}\right)\), and from this probability matrix computed the mutual information \(I\left({\bf{C}};\hat{{\bf{C}}}\right)\) between rewarded choice and the mouse’s choice using Shannon Information in equation (9), for any behavioral performance P. To remove any limited sampling bias, as we did for real data, we subtracted from \(I\left({\bf{C}};\hat{{\bf{C}}}\right)\) its shuffled values, computed after destroying the information by randomly shuffling the vector \(\hat{{\bf{C}}}\) (results average over 1,000 random shuffles).

Calculation of noise correlations and partialized noise correlations from pairs of neurons

We computed the noise correlations between each pair of neurons (Figs. 4–6) as Spearman (rank) correlations at fixed trial type, averaging across trial types. Noise correlations are usually computed as Pearson correlations at fixed trial type. Here we used Spearman correlations because we had evidence on nonlinearity of interactions (Extended Data Fig. 5j).