Abstract

Quantifying individual deviations in brain morphology from normative references is useful for understanding neurodiversity and facilitating personalized management of brain health. Here we report Chinese brain normative references using morphological imaging scans of 24,061 healthy volunteers from 105 sites, revealing later peak ages of lifespan neurodevelopmental milestones (1.2–8.9 years) than European/North American populations. We model individual brain deviation scores in 3,932 individuals with different neurological disorders from population references to evaluate three key aspects of brain health assessment using machine learning approaches: estimating disease propensity, predicting cognitive and physical outcomes and assessing treatment effects with distinct disability progression. The norm-deviation scores outperformed raw structural measures in these evaluations. Chinese-specific normative brain references may foster personalized diagnosis and prognosis in neurological diseases, enabling clinically applicable assessments of brain health.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Brain morphological imaging phenotype measures (approved by local centers) derived by FS have been shared at Science Data Bank in China (https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.o00133.00065) as part of the Chinese Color Nest Data Community (https://ccnp.scidb.cn/en). All the normative models and example data used for the statistical analyses and figures are publicly available at Science Data Bank in China (https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.o00133.00065).

Code availability

All code used for the statistical analyses and figures is publicly available at Science Data Bank in China (https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.o00133.00065) and GitHub (https://github.com/zhuozhizheng/Charting-Chinese-brain-health-and-neurological-disorders-across-lifespan).

References

GBD 2021 Nervous System Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of disorders affecting the nervous system, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Neurol. 23, 344–381 (2024).

Deuschl, G. et al. The burden of neurological diseases in Europe: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Public Health 5, e551–e567 (2020).

GBD 2015 Neurological Disorders Collaborator Group. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders during 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Neurol. 16, 877–897 (2017).

Risacher, S. L. & Saykin, A. J. Neuroimaging in aging and neurologic diseases. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 167, 191–227 (2019).

Cauda, F. et al. Brain structural alterations are distributed following functional, anatomic and genetic connectivity. Brain 141, 3211–3232 (2018).

van Oostveen, W. M. & de Lange, E. C. M. Imaging techniques in Alzheimer’s disease: a review of applications in early diagnosis and longitudinal monitoring. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 2110 (2021).

Sastre-Garriga, J., Pareto, D. & Rovira, A. Brain atrophy in multiple sclerosis: clinical relevance and technical aspects. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 27, 289–300 (2017).

Botvinik-Nezer, R. & Wager, T. D. Reproducibility in neuroimaging analysis: challenges and solutions. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 8, 780–788 (2023).

Young, P. N. E. et al. Imaging biomarkers in neurodegeneration: current and future practices. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 12, 49 (2020).

Bethlehem, R. A. I. et al. Brain charts for the human lifespan. Nature 604, 525–533 (2022).

Rutherford, S. et al. Evidence for embracing normative modeling. eLife 12, e85082 (2023).

Pini, L. et al. Brain atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease and aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 30, 25–48 (2016).

Fletcher, E. et al. Brain volume change and cognitive trajectories in aging. Neuropsychology 32, 436–449 (2018).

Rutherford, S. et al. The normative modeling framework for computational psychiatry. Nat. Protoc. 17, 1711–1734 (2022).

Worker, A. et al. Extreme deviations from the normative model reveal cortical heterogeneity and associations with negative symptom severity in first-episode psychosis from the OPTiMiSE and GAP studies. Transl. Psychiatry 13, 373 (2023).

Verdi, S. et al. Personalizing progressive changes to brain structure in Alzheimer’s disease using normative modeling. Alzheimers Dement. 20, 6998–7012 (2024).

Verdi, S. et al. Revealing individual neuroanatomical heterogeneity in Alzheimer disease using neuroanatomical normative modeling. Neurology 100, e2442–e2453 (2023).

Turney, I. C. et al. Brain aging among racially and ethnically diverse middle-aged and older adults. JAMA Neurol. 80, 73–81 (2023).

Tang, Y. et al. Brain structure differences between Chinese and Caucasian cohorts: a comprehensive morphometry study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 39, 2147–2155 (2018).

Kang, D. W. et al. Differences in cortical structure between cognitively normal East Asian and Caucasian older adults: a surface-based morphometry study. Sci. Rep. 10, 20905 (2020).

Tooley, U. A., Bassett, D. S. & Mackey, A. P. Environmental influences on the pace of brain development. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 22, 372–384 (2021).

Hibar, D. P. et al. Common genetic variants influence human subcortical brain structures. Nature 520, 224–229 (2015).

Han, Z. et al. Enriching population diversity in neuroscience. Sci. Bull. 70, 2560–2564 (2025).

Rosenbaum, P. R. Impact of multiple matched controls on design sensitivity in observational studies. Biometrics 69, 118–127 (2013).

ENIGMA Clinical High Risk for Psychosis Working Group. Normative modeling of brain morphometry in clinical high risk for psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry 81, 77–88 (2024).

Bedford, S. A. et al. Brain-charting autism and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder reveals distinct and overlapping neurobiology. Biol. Psychiatry 97, 517–530 (2025).

Williamson, E. J. & Forbes, A. Introduction to propensity scores. Respirology 19, 625–635 (2014).

Zhuo, Z. et al. Subtyping relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis using structural MRI. J. Neurol. 268, 1808–1817 (2021).

de Boer, A. A. A. et al. Non-Gaussian normative modelling with hierarchical Bayesian regression. Imaging Neurosci. 2, imag-2-00132 (2024).

Glasser, M. F. et al. A multi-modal parcellation of human cerebral cortex. Nature 536, 171–178 (2016).

Du, J. et al. Organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated within individuals: networks, global topography, and function. J. Neurophysiol. 131, 1014–1082 (2024).

Fan, L. et al. The Human Brainnetome Atlas: a new brain atlas based on connectional architecture. Cereb. Cortex 26, 3508–3526 (2016).

Bhalerao, G. V. et al. Construction of population-specific Indian MRI brain template: morphometric comparison with Chinese and Caucasian templates. Asian J. Psychiatr. 35, 93–100 (2018).

Haddad, E. et al. Multisite test–retest reliability and compatibility of brain metrics derived from FreeSurfer versions 7.1, 6.0, and 5.3. Hum. Brain Mapp. 44, 1515–1532 (2023).

Bozek, J., Griffanti, L., Lau, S. & Jenkinson, M. Normative models for neuroimaging markers: impact of model selection, sample size and evaluation criteria. NeuroImage 268, 119864 (2023).

Raine, P. J. & Rao, H. Volume, density, and thickness brain abnormalities in mild cognitive impairment: an ALE meta-analysis controlling for age and education. Brain Imaging Behav. 16, 2335–2352 (2022).

Sambuchi, N., Geda, Y. E. & Michel, B. F. Cingulate cortex in pre-MCI cognition. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 166, 281–295 (2019).

Weiner, M. W. et al. Recent publications from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: reviewing progress toward improved AD clinical trials. Alzheimers Dement. 13, e1–e85 (2017).

Prange, S., Metereau, E. & Thobois, S. Structural imaging in Parkinson’s disease: new developments. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 19, 50 (2019).

Krajcovicova, L., Klobusiakova, P. & Rektorova, I. Gray matter changes in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease and relation to cognition. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 19, 85 (2019).

Li, H. et al. Regional cortical thinning, demyelination and iron loss in cerebral small vessel disease. Brain 146, 4659–4673 (2023).

Li, H. et al. Dissociable contributions of thalamic-subregions to cognitive impairment in small vessel disease. Stroke 54, 1367–1376 (2023).

De Guio, F. et al. Brain atrophy in cerebral small vessel diseases: extent, consequences, technical limitations and perspectives: the HARNESS initiative. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 40, 231–245 (2020).

Manogaran, P. et al. Optical coherence tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, 1894 (2016).

Duan, Y. et al. Brain structural alterations in MOG antibody diseases: a comparative study with AQP4 seropositive NMOSD and MS. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 92, 709–716 (2021).

Masuda, H. et al. Silent progression of brain atrophy in aquaporin-4 antibody-positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 93, 32–40 (2022).

Armstrong, N. M. et al. Associations between cognitive and brain volume changes in cognitively normal older adults. NeuroImage 223, 117289 (2020).

Filippi, M. et al. Progressive brain atrophy and clinical evolution in Parkinson’s disease. NeuroImage Clin. 28, 102374 (2020).

Heinen, R. et al. Small vessel disease lesion type and brain atrophy: the role of co-occurring amyloid. Alzheimers Dement. 12, e12060 (2020).

Gilmore, J. H., Knickmeyer, R. C. & Gao, W. Imaging structural and functional brain development in early childhood. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19, 123–137 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all the contributors who provided magnetic resonance data from healthy volunteers. This work was supported by a grant from the Chinese Institutes for Medical Research, Beijing (CX23YZ01; Yaou Liu), the STI 2030-the major projects of the Brain Science and Brain-Inspired Intelligence Technology (2021ZD0200500; X.-N.Z.), the Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82330057; Yaou Liu), the Cross-Research Project of Beijing Science and Technology Star Program (20230484428; Yaou Liu), the National Science Foundation of China (822020840; Z. Zhuo), the Beijing Outstanding Young Scientist Program (JWZQ20240101025; Yaou Liu), the Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars (JQ20035; Yaou Liu), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China-National Key Research Project (2022YFC2009904; Yaou Liu), the Beijing Hospital Management Center-Climb Plan (DFL20220503; Yaou Liu), the Beijing Young Scholars (Yaou Liu), the Capital Medical University Young Scholars (Yaou Liu), the Young Scientists Program of Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University (YSP202205; Z. Zhuo), the Major Fund for International Collaboration of National Natural Science Foundation of China (81220108014; X.-N.Z.) and the National Basic Science Data Center ‘Interdisciplinary Brain Database for In vivo Population Imaging’ (ID-BRAIN; X.-N.Z.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design: Z. Zhuo, X.-N.Z. and Yaou Liu. Data analysis: Z. Zhuo, Yinshan Wang, P.G., J. Weng, R.Z. and Y. Duan. Statistical analysis: Z. Zhuo, L.C., Yinshan Wang, P.G. and X. Xu. Data collection: Z. Zhuo, L.C., Yinshan Wang, P.G., X. Xu, L.A., F.A., Yalin Bai, Yutong Bai, H.B., Q.C., J.C., Feiyan Chen, Feng Chen, K.C., Y.C., D.C., Z.C., H.D., D.D., Y. Du, G.F., Y.F., Z.G., L.G., C.G., M.G., Y.G., X.H., H.H., Y.H., B.H., J.H., C.-C.H., P.H., J. Lei, H.-J.L., Jianrui Li, Junlin Li, Kexuan Li, S. Li, W. Li, X.L., Yang Li, Yao Li, Yongmei Li, Yuna Li, Yunfei Li, P.L., H.L., C.-P.L., Jun Liu, Jungang Liu, W. Liu, Ying Liu, S. Lu, J. Luo, Y. Luo, S. Lui, H.M., N.M., Lanxi Meng, Linghui Meng, Y.Q., J.Q., M.R., J. Shao, Q.S., Y.S., Z.S., J. Sun, D.T., Y.T., F. Wang, Jinhui Wang, Junkai Wang, W.W., X.W., Yilong Wang, Yong Wang, Z.W., J. Weng, F. Wu, Ying Wu, Yuankui Wu, H.W., X. Xia, C.X., Jiaheng Xu, Jun Xu, R.X., S.X., P.Y., R. Yang, S.Y., X.Y., Y.Y., R. Yu, Z.Y., F. Zhang, H.Z., J. Zhang, N.Z., R.Z., T.Z., Y.Z., Zhanjun Zhang, Zhiqiang Zhang, Zhihua Zhang, J. Zhao, L. Zhao, Xiaohu Zhao, Xinxiang Zhao, Xin Zhao, X. Zhe, F. Zhou, J. Zhu, L. Zhu, Kuncheng Li, X.D., Y. Duan, X.-N.Z. and Yaou Liu. Paper writing: Z. Zhuo and X. Xu. Paper editing: L.C., Yinshan Wang, P.G., M.G., D.C., S.X., Yuna Li, J.H.C., X.-N.Z. and Yaou Liu.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J. Weng is an employee of Philips Healthcare, Shanghai, China. R.Z. is an employee of Neurosoft, Beijing, China. W. Liu is an employee of Sophmind Technology, Beijing, China. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Neuroscience thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

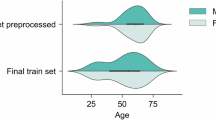

Extended Data Fig. 1 Details of included participants and their distributions.

a, A brief flowchart of the included participants in this study. b, Sample distributions across HC and disease groups, provinces and ages (HC, n = 24061; diseases, n = 3932). c, The distributions of Euler Number across age, sex and diagnostic groups (n = 27993). Note: HC, healthy control; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; PD, Parkinson’s disease; CSVD, cerebral small vessel disease; MS, multiple sclerosis; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder; yr, year.

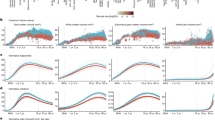

Extended Data Fig. 2 Comparisons of normative references by different FreeSurfer versions, different populations, and extended brain atlases.

a, The consistency analysis of the raw global and regional brain structural measures derived from FreeSurfer 6 and 7. b, The CH normative references fitted by the segmentation outputs of FreeSurfer 6 and 7, with the ENA and ENA-calibrated normative references as comparisons. The units are \(\times {10}^{4}{{mm}}^{3}\) for volume measures, \(\times {10}^{4}{{mm}}^{2}\) for area measure, and \({mm}\) for thickness measure. c, consistency analysis of the normative references (median curves) between different FreeSurfer version and populations. d, The milestones (peak ages) of normative references constructed by outputs of FreeSurfer 6. e, The peak age differences of regional structural normative references. Only the available peak ages in both CH and ENA normative references were displayed. f, The peak ages of the normative references based on the extended brain parcellation atlas, including HCP-MMP1.0 parcellation (Human Connectome Project Multi-Modal Parcellation version 1.0), DU15NET, and Brainnetome Atlases. Note: CH, Chinese; CCC, Concordance Correlation Coefficient; GMV, gray matter volume, sGMV, subcortical gray matter volume; WMV, white matter volume; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; v6, FreeSurfer version 6; v7, FreeSurfer version 7; yr, year.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Comparisons of normative references by GAMLSS and HBR framework.

a, The normative references fitted by GAMLSS and HBR framework. The units are \(\times {10}^{4}{{mm}}^{3}\) for volume measures, \(\times {10}^{4}{{mm}}^{2}\) for area measure, and \({mm}\) for thickness measure. b, The Z-scores across the site in GAMLSS and HBR fitting (n = 105 sites), the closer the median value to zero, the better the site effects mitigated. c, The classification AUC maps of each paired sites (n = 105 sites). The closer the AUCs to zero, the better the site effects mitigated. Note: GMV, gray matter volume, sGMV, subcortical gray matter volume; WMV, white matter volume; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; GAMLSS, generalized additive models for location, scale, and shape; HBR, hierarchical Bayesian regression; AUC, area under the curve.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Normative references by age censoring samples (aged 18-70 years) and downstream clinical tasks.

a, The fitted median curves and associated bootstrap CIs, of which, a majority of these global structural measures have narrow CIs, indicating a robust model fitting. The units are \(\times {10}^{4}{{mm}}^{3}\) for volume measures, \(\times {10}^{4}{{mm}}^{2}\) for area measure, and \({mm}\) for thickness measure. b, Sensitivity analysis of the estimated peak ages and median fitting curves with different resampled count of cases below 18 years. The units are \(\times {10}^{4}{{mm}}^{3}\) for volume measures, \(\times {10}^{4}{{mm}}^{2}\) for area measure, and \({mm}\) for thickness measure. c, The normative references constructed by age censoring samples (age limited to 18-70 years, n = 21,205). The units are \(\times {10}^{4}{{mm}}^{3}\) for volume measures, \(\times {10}^{4}{{mm}}^{2}\) for area measure, and \({mm}\) for thickness measure. d, Deviation score summary across diseases and global measures. e, Deviation score summary across diseases and regional measures. f, Milestones (peak ages) of age censoring normative references. g-j, Downstream clinical tasks using the age censoring normative references. Note: AUC, area under the curve; DPS, disease propensity score; HC, healthy control; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; PD, Parkinson’s disease; CSVD, cerebral small vessel disease; MS, multiple sclerosis; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; BVMT, Brief Visuospatial Memory Test; CVLT, California Verbal Learning Test; SDMT, Symbol Digit Modalities Test; PASAT, Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test; UPDRS, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale; EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; MAPE, mean absolute percentage error; DBS, deep brain stimulation; SPMS, secondary progressive multiple sclerosis; FDR, false discovery rate. All statistical tests were two-sided with FDR correction for multiple comparisons (if relevant). * pFDR < 0.05, ** pFDR < 0.005, *** pFDR < 0.001.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Deviation scores of global and regional structural measures in neurological diseases for female and male cases.

a, Deviation scores of global structural measures in neurological diseases for female and male cases. Statistical significances were presented for each disease group compared to age- sex- and site-matched HCs. * pFDR<0.05, ** pFDR<0.005, *** pFDR<0.001. b, Deviation scores of regional structural measures in neurological diseases for female and male cases. c, A summary of the most sensitive global and regional deviation scores (largest Cohen’s d) in each neurological disease, together with the corresponding overlapping coefficient and classification metrics. Note: HC, healthy control; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; PD, Parkinson’s disease; CSVD, cerebral small vessel disease; MS, multiple sclerosis; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder; ACC, accuracy; AUC, area under the curve; FDR, false discovery rate. All statistical tests were two-sided with FDR correction for multiple comparisons (if relevant).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Comparisons of clinical utility for detecting the alterations of global and regional brain structural measures in disease groups using Z-score and raw measures in conventional case-control methods.

a, The Z-score and raw measure of global measures across diseases. * pFDR<0.05, ** pFDR<0.005, *** pFDR<0.001. b, The Z-score and raw measure of regional measures across diseases. For raw measures, the t-values between disease and HCs were mapped on to the subcortical and cortical areas. c, A summary of the most sensitive global and regional deviation scores (largest Cohen’s d) in each neurological disease, together with the corresponding overlapping coefficient and classification metrics. d, the overlapped brain structural measures that showed statistical significance among the centile score, Z-score and raw measure. Note: GMV, gray matter volume, sGMV, subcortical gray matter volume; WMV, white matter volume; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; HC, healthy control; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; PD, Parkinson’s disease; CSVD, cerebral small vessel disease; MS, multiple sclerosis; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder; ACC, accuracy; AUC, area under the curve; FDR, false discovery rate. All statistical tests were two-sided with FDR correction for multiple comparisons (if relevant).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Comparisons of clinical utility of deviation score for DPS estimation using centile score, Z-score and raw measure.

a, Disease-specific model performance for classification of disease and HCs, and predicted DPS for HCs and diseases using different disease-specific models. b, Distribution of the predicted DPS for targeted disease and non-target groups. The disease-specific model should have high DPS for targeted diseases and low DPS for other groups. The targeted diseases using the corresponding disease-specific models were highlighted. The statistical test was conducted by ANOVA among centile score, Z-score and raw measure for each disease group. Note: AUC, area under the curve; DPS, disease propensity score; HC, healthy control; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; PD, Parkinson’s disease; CSVD, cerebral small vessel disease; MS, multiple sclerosis; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Comparisons of clinical utility for the prediction of clinical variables for HCs and diseases involving cognitive and physical scores using centile score, Z-score and raw measure.

a, The Pearson’s correlation between predicted and actual clinical measures and the MAPE of predictive models were presented. * pFDR < 0.05, ** pFDR < 0.005, *** pFDR < 0.001. b, The predicted PD motor outcomes by multivariate deviation scores. c, The risk-stratified MS and NMOSD by multivariate deviation scores. Note: HC, healthy control; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; PD, Parkinson’s disease; CSVD, cerebral small vessel disease; MS, multiple sclerosis; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; BVMT, Brief Visuospatial Memory Test; CVLT, California Verbal Learning Test; SDMT, Symbol Digit Modalities Test; PASAT, Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test; UPDRS, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale; EDSS, expanded disability status scale; MAPE, mean absolute percentage error; DBS, deep brain stimulation; SPMS, secondary progressive multiple sclerosis; FDR, false discovery rate. All statistical tests were two-sided with FDR correction for multiple comparisons (if relevant).

Extended Data Fig. 9 Additional univariate and multivariate analyses between disease groups.

a, The univariate Cohen’s d distribution of global and regional brain structural measures across diseases groups. b, A summary of the global and regional deviation scores showing largest Cohen’s d and corresponding overlapping coefficient and classification performance between disease groups and HCs. c, The univariate Cohen’s d between each paired disease groups. * pFDR<0.05, ** pFDR<0.005, *** pFDR<0.001. d, Multivariate classification between disease groups. SVM with 10-fold cross-validation was conducted, similar to the DPS model development. e, The contributing measures of the disease-specific classification models for DPS estimation. For each disease, the measures that selected in all the SVM 10-folds were defined as contributing measures, and they were ordered by their univariate Cohen’s d (HCs versus disease) in a decreasing manner. f, The confusion matrix of the disease-specific classification models for each disease. g, The distribution of DPS across diseases by using disease-specific classification models. ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. h, The distributions of 1000 permuted Pearson’s correlation and MAPE for clinical score and PD outcome prediction. j, The PD outcome prediction using baseline UPDRS alone. k, The univariate Pearson’s correlation between the deviation scores clinical scores across diseases. Note: MCI, mild cognitive impairment; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; PD, Parkinson’s disease; CSVD, cerebral small vessel disease; MS, multiple sclerosis; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder; AUC, area under the curve; GMV, gray matter volume; sGMV, subcortical gray matter volume; WMV, white matter volume; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; SVM, support vector machine; DPS, disease propensity score; MAPE, mean absolute percentage error; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; UPDRS, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale; EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; DBS, deep brain stimulation; FDR, false discovery rate. All statistical tests were two-sided with FDR correction for multiple comparisons (if relevant).

Extended Data Fig. 10 Assessment of the stability of deviation scores and disease development using longitudinal MR scans.

a, The deviation score changes of follow-up scans across measures and follow-up times in HCs. b, The deviation score changes of follow-up scans across measures and disease in a linear mixed model. c, An actionable clinical use of individual brain health report. A case of individual DPS and associated brain structural measure deviations. This case indicates that the DPS estimated by centile score is superior to that by raw measure to aid clinical decision-making. Note: HC, healthy control; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; PD, Parkinson’s disease; CSVD, cerebral small vessel disease; MS, multiple sclerosis; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder; m, month; yr, year; GMV, gray matter volume; sGMV, subcortical gray matter volume; lh, left hemisphere; rh, right hemisphere; DPS, disease propensity score; CI, confidence interval. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods, Results and References and Extended Data figure captions.

Supplementary Data 1

Supplementary Data 1. Univariate association between deviations and clinical scores.

Supplementary Data 2

Supplementary Data 2. Regional deviations with and without global measure regression.

Supplementary Data 3

Supplementary Data 3. An example of an individual brain health report.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhuo, Z., Chai, L., Wang, Y. et al. Charting brain morphology in international healthy and neurological populations. Nat Neurosci 29, 420–434 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02144-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02144-5