Abstract

RNA-guided DNA nucleases Cas9 and IscB (insertion sequences Cas9-like OrfB) are components of type II CRISPR–Cas adaptive immune systems and transposon-associated OMEGA (obligate mobile element-guided activity) systems, respectively. Sequence and structural comparisons indicate that IscB (~500 residues) evolved into Cas9 (~700–1,600 residues) through protein expansion coupled with guide RNA miniaturization. However, the specific sequence of events in this evolutionary transition remains unknown. Here, we report cryo-electron microscopy structures of four phylogenetically diverse RNA-guided nucleases—two IscBs and two Cas9s—each in complex with its cognate guide RNA and target DNA. Comparisons of these four complex structures to previously reported IscB and Cas9 structures indicate that evolution from IscB to Cas9 involved the loss of the N-terminal PLMP domain and the acquisition of the zinc-finger-containing REC3 domain, followed by bridge helix extension and REC1 domain acquisition. These structural changes led to expansion of the REC lobe, increasing the target DNA cleavage specificity. Additionally, the structural conservation of the RNA scaffolds indicates that the dual CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating crRNA guides of CRISPR–Cas9 evolved from the single ωRNA guides of OMEGA systems. Our findings provide insights into the succession of structural changes involved in the exaptation of transposon-associated RNA-guided nucleases for the role of effector nucleases in adaptive immune systems.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The structural models were deposited to the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 9K2Z (HfmIscB), 9K30 (TbaIscB), 9K31 (YnpsCas9) and 9K32 (NbaCas9). The cryo-EM density maps were deposited to the EM Data Bank under accession codes EMD-62001 (HfmIscB), EMD-62002 (TbaIscB), EMD-62003 (YnpsCas9) and EMD-62004 (NbaCas9). The raw images were deposited to the EM Public Image Archive under accession code EMPIAR-12424. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Barrangou, R. et al. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science 315, 1709–1712 (2007).

Garneau, J. E. et al. The CRISPR/Cas bacterial immune system cleaves bacteriophage and plasmid DNA. Nature 468, 67–71 (2010).

Wei, Y., Terns, R. M. & Terns, M. P. Cas9 function and host genome sampling in type II-A CRISPR–Cas adaptation. Genes Dev. 29, 356–361 (2015).

Heler, R. et al. Cas9 specifies functional viral targets during CRISPR–Cas adaptation. Nature 519, 199–202 (2015).

Jinek, M. et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337, 816–821 (2012).

Gasiunas, G., Barrangou, R., Horvath, P. & Siksnys, V. Cas9–crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, E2579–E2586 (2012).

Koonin, E. V., Gootenberg, J. S. & Abudayyeh, O. O. Discovery of diverse CRISPR–Cas systems and expansion of the genome engineering toolbox. Biochemistry 62, 3465–3487 (2023).

Wang, J. Y. & Doudna, J. A. CRISPR technology: a decade of genome editing is only the beginning. Science 379, eadd8643 (2023).

Kapitonov, V. V., Makarova, K. S. & Koonin, E. V. ISC, a novel group of bacterial and archaeal DNA transposons that encode Cas9 homologs. J. Bacteriol. 198, 797–807 (2015).

Altae-Tran, H. et al. The widespread IS200/IS605 transposon family encodes diverse programmable RNA-guided endonucleases. Science 374, 57–65 (2021).

He, S. et al. The IS200/IS605 family and ‘peel and paste’ single-strand transposition mechanism. Microbiol. Spectr. 3, 4 (2015).

Meers, C. et al. Transposon-encoded nucleases use guide RNAs to promote their selfish spread. Nature 622, 863–871 (2023).

Han, D. et al. Development of miniature base editors using engineered IscB nickase. Nat. Methods 20, 1029–1036 (2023).

Han, L. et al. Engineering miniature IscB nickase for robust base editing with broad targeting range. Nat. Chem. Biol. 20, 1629–1639 (2024).

Yan, H. et al. Assessing and engineering the IscB–ωRNA system for programmed genome editing. Nat. Chem. Biol. 20, 1617–1628 (2024).

Xue, N. et al. Engineering IscB to develop highly efficient miniature editing tools in mammalian cells and embryos. Mol. Cell 84, 3128–3140 (2024).

Kannan, S. et al. Evolution-guided protein design of IscB for persistent epigenome editing in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-025-02655-3 (2025).

Xu, C. et al. Conversion of IscB and Cas9 into RNA-guided RNA editors. Cell 188, 5847–5861 (2025).

Nishimasu, H. et al. Crystal structure of Cas9 in complex with guide RNA and target DNA. Cell 156, 935–949 (2014).

Anders, C., Niewoehner, O., Duerst, A. & Jinek, M. Structural basis of PAM-dependent target DNA recognition by the Cas9 endonuclease. Nature 513, 569–573 (2014).

Nishimasu, H. et al. Crystal structure of Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Cell 162, 1113–1126 (2015).

Hirano, H. et al. Structure and engineering of Francisella novicida Cas9. Cell 164, 950–961 (2016).

Yamada, M. et al. Crystal structure of the minimal Cas9 from Campylobacter jejuni reveals the molecular diversity in the CRISPR–Cas9 systems. Mol. Cell 65, 1109–1121 (2017).

Hirano, S. et al. Structural basis for the promiscuous PAM recognition by Corynebacterium diphtheriae Cas9. Nat. Commun. 10, 1968 (2019).

Sun, W. et al. Structures of Neisseria meningitidis Cas9 complexes in catalytically poised and anti-CRISPR-inhibited states. Mol. Cell 76, 938–952 (2019).

Fuchsbauer, O. et al. Cas9 allosteric inhibition by the anti-CRISPR protein AcrIIA6. Mol. Cell 76, 922–937 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Catalytic-state structure and engineering of Streptococcus thermophilus Cas9. Nat. Catal. 3, 813–823 (2020).

Hirano, S. et al. Structure of the OMEGA nickase IsrB in complex with ωRNA and target DNA. Nature 610, 575–581 (2022).

Schuler, G., Hu, C. & Ke, A. Structural basis for RNA-guided DNA cleavage by IscB–ωRNA and mechanistic comparison with Cas9. Science 376, 1476–1481 (2022).

Kato, K. et al. Structure of the IscB–ωRNA ribonucleoprotein complex, the likely ancestor of CRISPR–Cas9. Nat. Commun. 13, 6719 (2022).

Das, A. et al. Coupled catalytic states and the role of metal coordination in Cas9. Nat. Catalysis 6, 969–977 (2023).

Eggers, A. R. et al. Rapid DNA unwinding accelerates genome editing by engineered CRISPR–Cas9. Cell 187, 3249–3261 (2024).

Degtev, D. et al. Engineered PsCas9 enables therapeutic genome editing in mouse liver with lipid nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 15, 9173 (2024).

Ocampo, R. F. et al. DNA targeting by compact Cas9d and its resurrected ancestor. Nat. Commun. 16, 457 (2025).

Yang, J. et al. Insights into the compact CRISPR–Cas9d system. Nat. Commun. 16, 2462 (2025).

Wang, K. et al. Structural insights into type II-D Cas9 and its robust cleavage activity. Nat. Commun. 16, 7396 (2025).

Aliaga Goltsman, D. S. et al. Compact Cas9d and HEARO enzymes for genome editing discovered from uncultivated microbes. Nat. Commun. 13, 7602 (2022).

Bravo, J. P. K. et al. Structural basis for mismatch surveillance by CRISPR–Cas9. Nature 603, 343–347 (2022).

Pacesa, M. et al. R-loop formation and conformational activation mechanisms of Cas9. Nature 609, 191–196 (2022).

Xiao, Q. et al. Engineered IscB–ωRNA system with expanded target range for base editing. Nat. Chem. Biol. 21, 100–108 (2025).

Dugar, G. et al. CRISPR RNA-dependent binding and cleavage of endogenous RNAs by the Campylobacter jejuni Cas9. Mol. Cell 69, 893–905 (2018).

Rousseau, B. A., Hou, Z., Gramelspacher, M. J. & Zhang, Y. Programmable RNA cleavage and recognition by a natural CRISPR–Cas9 system from Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Cell 69, 906–914 (2018).

Chen, J. et al. trans-Nuclease activity of Cas9 activated by DNA or RNA target binding. Nat. Biotechnol. 43, 558–568 (2025).

Ran, F. A. et al. In vivo genome editing using Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Nature 520, 186–191 (2015).

Kim, E. et al. In vivo genome editing with a small Cas9 orthologue derived from Campylobacter jejuni. Nat. Commun. 8, 14500 (2017).

Nakagawa, R. et al. Engineered Campylobacter jejuni Cas9 variant with enhanced activity and broader targeting range. Commun. Biol. 5, 211 (2022).

Cofsky, J. C., Soczek, K. M., Knott, G. J., Nogales, E. & Doudna, J. A. CRISPR–Cas9 bends and twists DNA to read its sequence. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 29, 395–402 (2022).

Punjani, A. & Fleet, D. J. 3D variability analysis: resolving continuous flexibility and discrete heterogeneity from single particle cryo-EM. J. Struct. Biol. 213, 107702 (2021).

Jin, S. et al. Functional RNA splitting drove the evolutionary emergence of type V CRISPR–Cas systems from transposons. Cell 188, 6283–6300 (2025).

Karvelis, T. et al. Transposon-associated TnpB is a programmable RNA-guided DNA endonuclease. Nature 599, 692–696 (2021).

Nakagawa, R. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the transposon-associated TnpB enzyme. Nature 616, 390–397 (2023).

Sasnauskas, G. et al. TnpB structure reveals minimal functional core of Cas12 nuclease family. Nature 616, 384–389 (2023).

Altae-Tran, H. et al. Diversity, evolution, and classification of the RNA-guided nucleases TnpB and Cas12. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2308224120 (2023).

Omura, S. N. et al. Mechanistic and evolutionary insights into a type V-M CRISPR–Cas effector enzyme. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 30, 1172–1182 (2023).

Yoon, P. H. et al. Structure-guided discovery of ancestral CRISPR–Cas13 ribonucleases. Science 385, 538–543 (2024).

Zilberzwige-Tal, S. et al. Reprogrammable RNA-targeting CRISPR systems evolved from RNA toxin–antitoxins. Cell 188, 1925–1940 (2025).

Zhu, X. et al. Cryo-EM structures reveal coordinated domain motions that govern DNA cleavage by Cas9. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 26, 679–685 (2019).

Chen, J. S. et al. Enhanced proofreading governs CRISPR–Cas9 targeting accuracy. Nature 550, 407–410 (2017).

Dagdas, Y. S., Chen, J. S., Sternberg, S. H., Doudna, J. A. & Yildiz, A. A conformational checkpoint between DNA binding and cleavage by CRISPR–Cas9. Sci. Adv. 3, eaao0027 (2017).

Palermo, G. et al. Key role of the REC lobe during CRISPR–Cas9 activation by ‘sensing’, ‘regulating’, and ‘locking’ the catalytic HNH domain. Q. Rev. Biophys. 51, e91 (2018).

Pacesa, M. et al. Structural basis for Cas9 off-target activity. Cell 185, 4067–4081 (2022).

Yu, G., Smith, D. K., Zhu, H., Guan, Y. & Lam, T. T.-Y. ggtree: an R package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 8, 28–36 (2017).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M. & Gabaldón, T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973 (2009).

Wong, T. K. F. et al. IQ-TREE 3: phylogenomic inference software using complex evolutionary models. Preprint at EcoEvoRxiv https://doi.org/10.32942/X2P62N (2025).

Kalyaanamoorthy, S., Minh, B. Q., Wong, T. K. F., von Haeseler, A. & Jermiin, L. S. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 14, 587–589 (2017).

Guindon, S. et al. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59, 307–321 (2010).

Anisimova, M., Gil, M., Dufayard, J.-F., Dessimoz, C. & Gascuel, O. Survey of branch support methods demonstrates accuracy, power, and robustness of fast likelihood-based approximation schemes. Syst. Biol. 60, 685–699 (2011).

Minh, B. Q., Nguyen, M. A. T. & von Haeseler, A. Ultrafast approximation for phylogenetic bootstrap. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 1188–1195 (2013).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Wohlwend, J. et al. Boltz-1 democratizing biomolecular interaction modeling. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.11.19.624167 (2025).

Punjani, A., Rubinstein, J. L., Fleet, D. J. & Brubaker, M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017).

Punjani, A., Zhang, H. & Fleet, D. J. Non-uniform refinement: adaptive regularization improves single-particle cryo-EM reconstruction. Nat. Methods 17, 1214–1221 (2020).

Rosenthal, P. B. & Henderson, R. Optimal determination of particle orientation, absolute hand, and contrast loss in single-particle electron cryomicroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 333, 721–745 (2003).

Cardone, G., Heymann, J. B. & Steven, A. C. One number does not fit all: mapping local variations in resolution in cryo-EM reconstructions. J. Struct. Biol. 184, 226–236 (2013).

Tan, Y. Z. et al. Addressing preferred specimen orientation in single-particle cryo-EM through tilting. Nat. Methods 14, 793–796 (2017).

Cowtan, K. Automated nucleic acid chain tracing in real time. IUCrJ 1, 387–392 (2014).

Hoh, S. W., Burnley, T. & Cowtan, K. Current approaches for automated model building into cryo-EM maps using Buccaneer with CCP-EM. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 76, 531–541 (2020).

Burnley, T., Palmer, C. M. & Winn, M. Recent developments in the CCP-EM software suite. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 73, 469–477 (2017).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010).

Sanchez-Garcia, R. et al. DeepEMhancer: a deep learning solution for cryo-EM volume post-processing. Commun. Biol. 4, 874 (2021).

Afonine, P. V. et al. Real-space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 74, 531–544 (2018).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 1948–1954 (2002).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 (2010).

Yamashita, K., Palmer, C. M., Burnley, T. & Murshudov, G. N. Cryo-EM single-particle structure refinement and map calculation using Servalcat. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 77, 1282–1291 (2021).

Nicholls, R. A., Fischer, M., McNicholas, S. & Murshudov, G. N. Conformation-independent structural comparison of macromolecules with ProSMART. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 70, 2487–2499 (2014).

Williams, C. J. et al. MolProbity: more and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation. Protein Sci. 27, 293–315 (2018).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF ChimeraX: structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 30, 70–82 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Makarova for assistance with the phylogenetic analysis and staff scientists at The University of Tokyo’s cryo-EM facility, especially Y. Sakamaki, for help with cryo-EM data collection. N.N. is supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI grant number 25KJ1023. K.K. was supported by a grant from the Mitsubishi Foundation. F.Z. is supported by National Institutes of Health grants (1DP1-HL141201 and 2R01HG009761-05), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Open Philanthropy, the Edward Mallinckrodt, Jr. Foundation, the Poitras Center for Psychiatric Disorders Research at MIT, the Hock E. Tan and K. Lisa Yang Center for Autism Research at MIT, the Yang-Tan Molecular Therapeutics Center at McGovern, the Phillips family and J. and P. Poitras. H.N. is supported by the Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research) from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development under grant number JP21am0101115 (support number 2792), JSPS KAKENHI grant numbers 21H05281 and 25H00436, the Takeda Medical Research Foundation and the Inamori Research Institute for Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.N., K.K. and S.Y., with assistance from S.O. and Y.I., performed the biochemical experiments. N.N., K.K., S.Y., M.H., K.Y. and H.N. performed the structural analyses. S.K., with assistance from F.Z., performed the TAM/PAM screening experiments. N.N. and H.N., with assistance from S.Y., K.K., S.K., M.H., K.Y. and E.V.K., wrote the manuscript. H.N. supervised the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

F.Z. is a scientific advisor and cofounder of Editas Medicine, Beam Therapeutics, Pairwise Plants, Arbor Biotechnologies and Proof Diagnostics. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Structural & Molecular Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available. Primary Handling Editor: Melina Casadio, in collaboration with the Nature Structural & Molecular Biology team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 TAM/PAM specificities of IscBs and Cas9s.

(a) Weblogo motifs of TAMs for HfmIscB and TbaIscB and PAMs for YnpsCas9 and NbaCas9. (b–e) TAM/PAM recognition by HfmIscB (b), TbaIscB (c), YnpsCas9 (d), and NbaCas9 (e). Schematics and structures are shown on the top and bottom, respectively. Cryo-EM density maps for TAM/PAM-interacting residues and the DNA molecules are shown as gray semitransparent surfaces. Disordered nucleotides are indicated by dotted lines in (b). In the HfmIscB structure, dG3*, dA4*, dG5*, and dG6* are recognized by K388, N379, Y372, and K389 through base-specific hydrogen-bonding interactions, respectively. Although our biochemical data indicate the preference for the second G nucleotide in the TAM, the dG2* nucleobase does not directly contact the HfmIscB protein, suggesting that dG2* is recognized by nearby residues, such as H380 and Q381, via water-mediated hydrogen bonds. In the TbaIscB structure, dG1* and dG2* are recognized by Q504 and N416, respectively. It is likely that G at position 3* in the PAM is recognized by K497. While YnpsCas9 recognizes dC−2 and dG3* using K580 and K642, respectively, NbaCas9 contacts dG2* and dC−2 using N638/R722 and K636, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Multiple sequence alignment.

Multiple sequence alignment of HfmIscB, TbaIscB, YnpsCas9, and NbaCas9. HfmIscB, IscB from the human fecal metagenome (Ga0169696_100022); TbaIscB, IscB from Tissierellia bacterium (JAAZKS010000250.1); YnpsCas9, Cas9 from the sediment metagenome in Yellowstone National Park (Ga0315277_10040887); NbaCas9, Cas9 from Nitrospirae bacterium (MHDT01000042.1). The figure was prepared using Clustal Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/jdispatcher/msa/clustalo) and ESPript 3.0 (https://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/ESPript).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Structural comparison of the IscB and Cas9 orthologs.

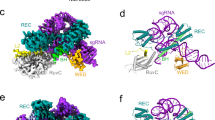

Structures of the nuclease–guide RNA–target DNA complexes for HfmIscB, TbaIscB, OgeuIscB (PDB: 7XHT), YnpsCas9, NbaCas9, Acidothermus cellulolyticus Cas9 (AcCas9) (PDB: 8D2L), Campylobacter jejuni Cas9 (CjCas9) (PDB: 5X2G), Francisella novicida Cas9 (FnCas9) (PDB: 5B2O), and Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) (PDB: 5F9R).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Structural comparison of the REC regions.

(a) Structural comparison of the REC3 domains of TbaIscB, YnpsCas9, NbaCas9, AcCas9 (PDB: 8D2L), FnCas9 (PDB: 5B2O), and SpCas9 (PDB: 5F9R). Zinc ions are shown as gray spheres. The zinc-coordinating residues are shown as stick models. Disordered residues are indicated by dotted lines. (b) Guide–target heteroduplex recognition by the REC regions of HfmIscB, TbaIscB, OgeuIscB (PDB: 7XHT), YnpsCas9, NbaCas9, AcCas9 (PDB: 8D2L), CjCas9 (PDB: 5X2G), FnCas9 (PDB: 5B2O), and SpCas9 (PDB: 5F9R). βHI, β-hairpin insertion. The α-helices comprising the helix bundles are numbered.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Sequence and structural diversity of IscB-L.

(a) Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of IscB-L. The nine clades of IscB-L are highlighted in different colors, with selected orthologs indicated by dots. (b) Cryo-EM structure of OgeuIscB (PDB: 7XHT) and predicted models of selected IscB-L orthologs. The models were predicted by Boltz-1. The PLMP, HNH, WED, and TI domains and the L1/L2 linkers are shown as semitransparent ribbon models for clarity.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Recognition of the first stem, TAM/PAM-proximal heteroduplex, and central stem.

(a–d) Recognition of the first stems (the guide adaptor stem for HfmIscB and the repeat:antirepeat duplex for TbaIscB and Cas9s), the TAM/PAM-proximal heteroduplex, and the central stem by the HfmIscB (a), TbaIscB (b), YnpsCas9 (c), and NbaCas9 (d) complexes. The residues and nucleotides forming hydrogen bonding and stacking interactions are depicted as stick models. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by dashed lines. SL, stem loop; GAS, guide adaptor stem; R:AR, repeat:antirepeat; RH, recognition hairpin; RS, recognition stem; CS, central stem; NS, nexus stem.

Extended Data Fig. 7 RuvC and HNH active sites of the Cas9 nucleases.

(a) Structural comparison of the DNA targets bound to the RuvC and HNH active sites between YnpsCas9, NbaCas9, and SpCas9 (PDB: 7Z4J). The active residues of the RuvC and HNH domains are shown as space-filling models. Disordered regions are indicated by dotted lines. TS, target DNA strand; NTS, nontarget DNA strand. (b) Recognition of the NTS in the RuvC active sites of YnpsCas9, NbaCas9, and SpCas9. Magnesium ions are shown as gray spheres. Hydrogen and coordinate bonds are indicated by dashed lines. (c) Recognition of the TS in the HNH active sites of YnpsCas9, NbaCas9, and SpCas9. Magnesium ions and water molecules are shown as gray and red spheres, respectively. Hydrogen and coordinate bonds are indicated by dashed lines.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Nonspecific single-stranded RNA cleavage by TbaIscB.

(a) In vitro RNA and DNA cleavage activities of WT TbaIscB and its active-site mutants. The TbaIscB protein (WT, dRuvC, or dHNH) was incubated with either the Cy5-labeled single-stranded RNA (ssRNA), double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), or ssDNA substrate (60 nt) at 37 °C for 1 or 5 min, and then the reaction was analyzed by 15% urea-PAGE. dRuvC, D59A; dHNH, H256A. (b) In vitro ssRNA cleavage activities of TbaIscB, HfmIscB, YnpsCas9, and NbaCas9. The Cy5-labeled ssRNA substrate (60 nt) was incubated with either the TbaIscB, YnpsCas9, or NbaCas9 protein, or the HfmIscB–ωRNA complex at 37 °C for 1 or 60 min, and then the reaction was analyzed by 15% urea-PAGE. HfmIscB was only purified as the ribonucleoprotein complex. In (a) and (b), experiments were repeated three times with similar results. (c) Multiple sequence alignment of the HNH domains from TbaIscB, NmCas9, CjCas9, OgeuIscB, HfmIscB, YnpsCas9, and NbaCas9. Key residues for RNA cleavage are highlighted in red. (d) Structural comparison of the HNH domains of TbaIscB (AlphaFold2 model) and NmCas9 (PDB: 8JA0).

Extended Data Fig. 9 Structural comparison of the active states of Cas9s.

(a) Structural comparison of the active states of YnpsCas9, NbaCas9, AcCas9 (PDB: 8D2L), and SpCas9 (PDB: 7Z4J). The HNH domains and the L1/L2 linkers are shown as ribbon models, while the rest of the complex is shown as surface models. (b, c) Interactions of the HNH domain with the REC linker and sgRNA (b) and with the WED domain (c) in the YnpsCas9 active state. (d and e) Interactions of the HNH domain with the REC1 domain (d) and with the WED domain (e) in the NbaCas9 active state. (f) Comparison of the spatial arrangements between the RuvC/HNH domains and the L1/L2 linkers in YnpsCas9, NbaCas9, AcCas9 (PDB: 8D2L), and SpCas9 (PDB: 7Z4J). The residues interacting with NTS nucleobases are shown as space-filling models.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Sequence and structural diversity of IsrB, IscB-S, IscB-L, and type II-D Cas9.

(a) Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of IsrB, IscB, and type II-D Cas9, built based on their RuvC domains and bridge helices. The branches of IsrB, IscB-S, IscB-L, and type II-D Cas9 are highlighted in different colors. The CRISPR-associated and non-CRISPR-associated orthologs are indicated by gray and white dots, respectively. (b) Cryo-EM structures of DtIsrB (PDB: 8DMB), OgeuIscB (PDB: 7XHT), HfmIscB, TbaIscB, YnpsCas9, NbaCas9 and predicted models of selected IscBs (55826, 6734, 13572, 40754, 26022, and 48100). The models were predicted by Boltz-1. The PLMP, HNH, WED, and TI/PI domains and the L1/L2 linkers are shown as semitransparent ribbon models for clarity. The zinc ion and the zinc-coordinating residues are shown as space-filling models. ZF, zinc finger.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–13.

Supplementary Table 1

DNAs and RNAs used in this study.

Supplementary Video 1

Cryo-EM structure of the HfmIscB–ωRNA–target DNA complex.

Supplementary Video 2

Cryo-EM structure of the TbaIscB–ωRNA–target DNA complex.

Supplementary Video 3

Cryo-EM structure of the YnpsCas9–guide RNA–target DNA complex.

Supplementary Video 4

Cryo-EM structure of the NbaCas9–guide RNA–target DNA complex.

Supplementary Video 5

A 3D variability analysis of the HfmIscB–ωRNA–target DNA complex.

Supplementary Video 6

A 3D variability analysis of the TbaIscB–ωRNA–target DNA complex.

Supplementary Video 7

A 3D variability analysis of the YnpsCas9–guide RNA–target DNA complex.

Supplementary Video 8

A 3D variability analysis of the NbaCas9–guide RNA–target DNA complex.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1 and Extended Data Figs. 5 and 10

Cluster and sequence information and tree files used in the phylogenetic analyses.

Source Data Figs. 5 and 6 and Extended Data Fig. 8

Uncropped gel images.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Nagahata, N., Kato, K., Yamada, S. et al. Structural visualization of the molecular evolution of CRISPR–Cas9. Nat Struct Mol Biol (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-025-01743-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-025-01743-x