Abstract

Transcranial electrical stimulation (tES) has gained substantial momentum as a research and therapeutic tool; however, it suffers from challenges related to reproducibility and quality assessment due to the absence of standardized reporting practices. Here we aim to develop a comprehensive and consensus-based checklist for conducting and reporting tES studies to enhance the quality of research and reports. In this Consensus Statement, we used a Delphi approach conducted across three rounds and involving 38 experts to identify crucial elements required to report in tES studies. This consensus-driven approach included the evaluation of the interquartile deviation (>1.00), the percentage of positive responses (above 60%) and mean importance ratings (<3), hence ensuring the creation of a robust and well-balanced checklist. These metrics were utilized to assess both the consensus reached and importance ratings for each item. Consensus was reached, leading to the retention of 66 out of the initial 70 items. These items were categorized into five groups: participants (12 items), stimulation device (9 items), electrodes (12 items), current (12 items) and procedure (25 items). We then distilled a shorter version of the checklist, which includes the 26 items deemed essential. The Report Approval for Transcranial Electrical Stimulation (RATES) checklist is relevant to those carrying out and assessing tES studies, as it provides a structured framework for researchers to consider and report. For reviewers, it can serve as a tool to assess completeness, comprehensiveness and transparency of reports. In addition, the RATES checklist aims to promote a deeper understanding of tES and facilitates comparisons between studies within the field. Overall, the RATES checklist provides a shared reference point that may improve research quality, foster harmonization in reporting and, ultimately, enhance the interpretability and reproducibility of findings in both research and clinical contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Interest in neurostimulation interventions has soared in recent decades1. Noninvasive brain stimulation (NIBS) techniques offer a promising opportunity for modulation of brain excitability, and activity in health and disease2,3. Transcranial electrical stimulation (tES) is a NIBS intervention that has gained substantial momentum as a research and therapeutic tool in recent decades. tES involves applying electrical current to the brain to alter cortical excitability and activity4. Currently, the three main tES techniques are transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) and transcranial random noise stimulation. These tES interventions offer the advantage of being portable and relatively simple to apply, compared with other interventions5. The effectiveness of tES critically relies on the careful selection of stimulation parameters and study procedures. tDCS modifies resting membrane potentials of neurons through alteration of cortical excitability, depending on the applied parameters and the stimulated brain region4,6,7. Prolonged stimulation results in neuroplastic after-effects8,9. tACS involves applying alternating currents to the scalp, which is thought to synchronize cortical oscillations10,11. A third form of tES, transcranial random noise stimulation, administers a balanced spectrum of random electrical oscillations to the brain, adding a stochastic component to the neural activity, enhancing excitability of underlying cerebral regions12.

Even slight variations of stimulation parameters can lead to notable changes of the stimulation effects, including reversal of its intended outcome8,9,13. In recent years, numerous studies have been devoted to optimizing the parameters of tES to enhance its efficacy and effectiveness. These studies detailed how intervention parameters modulate tES effects14,15,16,17 and aimed to explore various aspects of tES, including the selection of optimal current intensity18,19, duration of stimulation20, combination of duration and intensity21,22,23,24,25, position, size and distance of electrodes26,27, total number of sessions to deliver and duration between them28, stimulation frequency29,30,31 or combination of parameters using artificial intelligence32,33. Incorporating these methodological aspects into research papers that apply tES holds promise to reduce methodologically induced variability of stimulation effects, thereby advancing the field’s precision and reproducibility.

Numerous studies have defined crucial tES parameters, including technical guides34,35, guidelines36,37, nomenclature definition38 and reviews of intervention parameters39,40,41. The majority of these studies have primarily focused on stimulation parameters. In summary, a considerable number of empirical studies so far failed to report all relevant information, and existing guidelines often lack coverage of all essential aspects. The objective of this study is to comprehensively sum up all relevant elements that should be reported and establish a consensus that will have broad applicability.

This study aims to provide a comprehensive tool for researchers to enhance the completeness and quality of documentation of study designs, stimulation parameters and outcome measures. Complete and transparent reporting improves replicability of studies, comparability and complex post hoc analyses, such as meta-analysis. Previous studies have shown that incorporation of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement not only resulted in improved reporting quality of randomized clinical trials42,43,44 but also had a subsequent positive effect on meta-analytic approaches45.

We aimed to develop a consensus-based checklist for reporting tES parameters. Through an iterative process involving expert panel members and the Delphi method, we aimed to establish a comprehensive set of criteria that addresses various relevant aspects of tES studies, including stimulation parameters, electrode positioning, timing, stimulator characteristics and experimental procedures. Fostering a standardized approach for reporting essential tES study features will advance the field of tES.

Method

The methodology used in this study utilized an observational approach through an online Delphi technique. The Delphi technique is an effective means to attain consensus among experts on a particular topic46,47,48,49. This method involves a series of sequential questionnaires, commonly referred to as rounds, interspersed with controlled feedback, aiming to derive a reliable consensus of opinions48. Controlled feedback entails presenting participants with summaries of data from each round, ensuring that the process continues until a group consensus is achieved. This iterative process enables a dynamic exchange of ideas and perspectives. As participants engage with the evolving consensus-building process, they are prompted to critically evaluate their initial positions and consider alternative viewpoints presented by their peers. This iterative nature of controlled feedback serves to enhance the depth and quality of the discussions within the expert panel50. The Delphi method’s multifaceted advantages have led to its common application in developing consensus-based checklists51,52,53,54,55,56. As such, it is an appropriate and effective approach for the objective of developing a comprehensive and reliable checklist for reporting practice of tES studies.

Steering committee

The steering committee, consisting of three authors, M.A.N., V.N. and Z.V., was responsible for conceptualizing study objectives, defining the methodology and outlining the overarching goals. Drawing from the existing literature, the committee formulated the initial checklist items as a foundation for the Delphi process. Additionally, the committee was involved in participant selection, ensuring a diverse expert panel.

To ensure a systematic, transparent and repeatable recruitment process for assembling the expert panel, we established a clear and replicable procedure for generating the list of invitees. First, we identified potential experts by systematically searching academic databases such as PubMed and Scopus using keywords related to tES. We filtered candidates on the basis of specific criteria: a robust publication record with a minimum of ten tES publications in the past 5 years and affiliation with reputable universities or research centers and/or a substantial citation count (more than 5,000) of their work and/or previous active contributions to the development of guidelines and protocols. Additionally, we cross-referenced this list with peer recommendations and previous collaboration records to ensure a well-rounded selection. This structured approach not only facilitates transparency and repeatability in the recruitment process but also permits verification and testing of the methodology by external reviewers.

The steering committee maintained active communication with the panel members, facilitating the smooth execution of the Delphi survey. Through their oversight and collaboration, the steering committee shaped the entire Delphi study, from its inception to the incorporation of the expert consensus-driven results.

Questionnaire design

The primary objective of the Report Approval for Transcranial Electrical Stimulation (RATES) study was to establish a consensus between experts in the field of tES concerning indispensable items for a checklist. This checklist aims to serve as a fundamental tool for systematically reporting and evaluating tES studies. The initial phase involved the extraction of items from existing studies based on a comprehensive literature review. In this phase, a content analysis was conducted using the snowball sampling method. This method involved systematically reviewing and extracting data from a set of optimization, review and guideline studies in the field5,34,35,37,38,39,40,41,57,58,59,60. We began with a key set of studies known to focus on the optimization of tES parameters. From these initial studies, we then expanded our scope by identifying and including additional relevant studies through a process of citation tracking. This iterative process allowed us to gather a collection of parameters as the checklist items. Subsequently, these items were categorized into five distinct sections, namely stimulator (device), electrodes, current, timing and procedure. This structured organization ensured a comprehensive coverage of essential elements relevant to tES research. These categories were extended further based on the items added by experts. The steering committee collated the items and converted them into a standardized format, and then pilot-tested the checklist. Three experts, selected to be representative of the wider sample, engaged in the pilot test using a web-based questionnaire. The aim was to evaluate the clarity of participant instructions and the overall functionality of the questionnaire. The insights gained from the pilot test prompted minor adjustments to the wording of certain items to enhance clarity and comprehension. This preparatory step ensured that the questionnaire was both user-friendly and effective for the subsequent rounds of the Delphi study.

Procedure

Following the initial phase described above, the members of the expert panel were chosen. This process was guided by recommendations of the steering committee, coupled with an exploration of available tES literature across different relevant databases, including Google Scholar, PubMed and Scopus. After refinement of the expert list, personalized emails were dispatched to these individuals, which included a detailed description of the study objectives, stages and timeline. A reminder email was sent 1 week after the first contact in case of no reply. This approach was also used in the subsequent rounds of the study to minimize dropouts. Respondent panelists were invited to partake in a maximum of three rounds of this web-based questionnaire, with the process unfolding systematically over time.

In the initial round, experts were supplied with the initial checklist of items related to tES studies via an editable Word document. Their task was to rate the importance of each item and also have the option to suggest new items or revisions of existing ones. To measure the importance of each item, experts were guided to use a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not important) to 5 (extremely important). Subsequently, a consolidated checklist was formulated by amalgamating all revisions, feedback and novel entries into a single comprehensive document. This revised checklist was then disseminated among the members of the steering committee for implementation and further refinement. In the second round, experts were supplied with the revised checklist, incorporating the additions and modifications based on their collective feedback from the first round. Experts were invited to evaluate newly introduced items by the same Likert scale as was used in the first round.

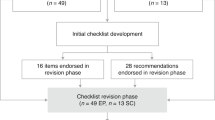

In the second round, all items from the first round, along with the individual ratings provided by each panelist, were retained. Panelists were instructed to rate the new items and were given the opportunity to re-evaluate the first-round items and provide new ratings, but none of them chose to make any changes to their initial ratings. This stage was designed to enable experts to reconsider their ratings on the basis of any new insights or changes of items resulting from the earlier round. In the third and final round, experts were presented with the mean ratings of each item from the previous round. This gave them information about the aggregated opinion of the group. Experts were subsequently requested to re-rate each item, considering the mean ratings as well as the discussions in the preceding rounds. Additionally, experts were prompted to propose whether an item should be retained in or omitted from the ultimate checklist via a yes/no question about the criticality of each item, that is, if an item is essential or just nice to have, in a fourth round. The data gathering phase, spanning three rounds, extended over ~3 months, from early June 2023 to late August 2023. Overall, this three-phase Likert scale-based assessment established a systematic and iterative framework. It allowed experts to not only express their individual viewpoints but also refine them via response to feedback. The culmination of this process was the attainment of a shared consensus among experts on the pivotal criteria for effectively reporting and conducting tES studies, Fig. 1.

An outline of the step-by-step procedure of expert panel selection, initial checklist distribution and the three iterative Delphi rounds. In each round, experts rated item importance using a five-point Likert scale and provided suggestions for additions or revisions. Successive rounds incorporated expert feedback, and participants were given the opportunity to re-rate items and evaluate new entries. The final round included aggregated group ratings and a yes/no vote to determine essential checklist items.

Data analysis

The data were entered into Microsoft Excel and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Version 28). Each round of the Delphi process involved a transformation of responses into average values on a five-point Likert scale, offering a consolidated view of the panelists’ opinions. Fountain graphs were produced to present the statistical trends within the panel’s responses across the different rounds of the study. These graphs provide a visual representation that permits a clear understanding of how expert opinions evolved and converged over the course of the study. Furthermore, interquartile deviation (IQD) scores, which represent the difference between the 75th and 25th percentiles, served as an indicator of consensus. Lower IQD values are indicative for a stronger consensus61. Importantly, a stringent threshold of an IQD of 1.00 or less was determined as indicative for consensus62.

Furthermore, positive ratings (scores of 4 and 5 on the rating scale, corresponding to ‘very important’ and ‘extremely important’, respectively) were considered as the measure of importance, namely percentage of positive responses (PPR). In this study, a PPR exceeding 60% was established as the threshold for importance. Another criterion for decision-making was mean rating, indicating the average rating assigned by the experts to each item. Items with a mean rating of 3 or higher were retained in the checklist, based on panelist suggestion. In sum, the consensus decision-making process involved the assessment of three key metrics: IQD, PPR and mean rating. The criteria of IQD ≤1.0 and ≥60% positive responses from the panelists served as the basis for including a factor in the checklist57. If an item did not meet the PPR criteria, the mean rating was used for the decision to remove (3 < mean rating) or retain it (3 ≥ mean rating). This multicriteria approach aimed to keep balance between the perceived importance of an item, the degree of consensus among experts, and the need for a focused and concise checklist. This facilitated a nuanced and data-driven decision-making process, ensuring that the final checklist items reflect both expert consensus and practical relevance for tES studies. For the shortened version of the checklist, we retained items that achieved an 80% consensus on their essentiality.

The reliability of the responses in the third round was evaluated using Cronbach’s α coefficient, an index of internal consistency or homogeneity of the panelists’ responses63. An α value of ≥0.80 was set as the threshold for evaluation of internal consistency and reliability of the scale.

To evaluate the reproducibility and transparency of published tES studies, we considered studies from the past decade, 2014–2024, using PubMed. We selected five studies from each year, resulting in a total of 50 studies. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to ensure that the studies were peer reviewed, primary research on tES and available in full text. The studies were organized by publication year, and for each year, five studies were randomly selected from the list to ensure a representative sample. Relevant information, such as journal impact factor and adherence to the full and short version of the RATES checklist, was then extracted for further analysis. This systematic approach ensures an unbiased selection process across the specified timeframe. Each study was assessed for adherence to the RATES checklist by two independent raters (Z.V. and M.A.S.), with inter-rater reliability evaluated using Cohens’ \({\kappa}\) statistic, for which a value greater than 0.8 indicates ‘almost perfect agreement’. In addition, the relationship between reporting scores and publication year and journal impact factor was examined.

Results

Out of the 123 experts who were invited to participate in the first round in June 2023, with a 1-week time window to confirm their participation via the initial email and an additional 1-week time window to reply to the reminder, 56 (45.5%) accepted to join the panel. Six experts replied to the invitation but declined to participate in the study. Four of them mentioned busy schedules as reason, one was primarily focused on the field of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) rather than tES, and one disagreed with the study’s methodology. From the group who accepted to join, 11 experts did not complete the first-round checklist, 5 did not complete the second-round checklist and 2 did not complete the third-round checklist. The characteristics of the expert panel members are shown in Table 1.

The panel members collectively showed extensive experience in NIBS, with a range of 8–31 years and a mean (standard deviation (s.d.)) of 18.34 (7.21) years. The distribution in terms of academic positions was as follows: full professors (n = 23), associate professors (n = 4), assistant professors (n = 3), lecturers (n = 5) and postdoctoral fellows (n = 3). The final panel of 38 experts consisted of 12 female participants and 26 male participants. In terms of geographic and gender diversity, our participants were from five different continents, with gender representation as follows: Asia (1 female), Australia (2 females, 4 males), Europe (10 females, 15 males), North America (5 males) and South America (1 male).

The original checklist encompassed 50 distinct items, categorized into five specific domains: ‘stimulator’ (device) with 9 items, ‘electrodes’ featuring 9 items, ‘current’ having 7 items, ‘timing’ containing 9 items and, lastly, ‘procedure parameters’ consisting of 16 items. Applying a criterion of a 60% cut-off for positive responses from the panelists, all items from the first round successfully passed and progressed to the second round. For the second round, this checklist underwent substantial changes based on comments from the panelists. Specifically, 20 novel items were incorporated into the inventory, further enriching its comprehensiveness. Simultaneously, the structure of categorization was refined, yielding five streamlined categories: ‘stimulator (device)’ maintaining 9 items, ‘electrodes’ expanding to 12 items and ‘current’ extending to 12 items. Moreover, the ‘procedure parameters’ category was expanded to 25 items. Notably, the items initially located within the ‘timing’ category were integrated into other domains, and a new category labeled ‘Participants’ was introduced, with 12 items. In addition to these revisions, relevant improvements were introduced by the experts during the initial round. These encompassed explanations or further contextual information pertaining to the original items. This augmentation during the first round of expert evaluation culminated in the second iteration of the checklist, which ultimately spanned 70 distinct items spanning the five categories: ‘participants’, ‘stimulator’ (device), ‘electrodes’, ‘current’ and ‘procedure parameters’.

Figure 2 shows the mean and s.d. of ratings of all 70 items in the first and second (where ratings were identical, as explained above), and third iterations. These graphs, resembling fountains, provide a comprehensive visual representation of consensus convergence64. The graphs specifically illustrate the alignment of ratings. Notably, the outcomes from the initial and final rounds suggest convergence of consensus regarding the factors encompassed in the questionnaire. This is characterized by lower s.d. values (final round versus initial rounds, 0.72 versus 0.84), further underscoring the increasing agreement among experts as the rounds progressed. Furthermore, a larger relative proportion of means were falling within the 4–5 range in the final round, showing that more items are rated as important. This trend was also reflected in the increase of overall mean ratings and the reduction in s.d. values from the initial to the final round, highlighting both stronger agreement on item importance and reduced variability across the panel. Table 2 presents the metrics of checklist items in the initial and final ratings of the study. Figure 3 depicts a stacked bar graph for the ratings of the third-round checklist.

The left graph shows ratings from the first and second rounds (ratings were identical in these two rounds) and the right graph shows ratings from the final (third) round. The reduction in s.d. values observed in the final round, relative to the initial rounds, suggests converging opinions and enhanced consensus.

The dark blue, purple, light purple, light red and red coloring refers to extremely important, very important, moderately important, somewhat important and not important, respectively. The x axis represents the percentage of choices selected by panelists, whereas the y axis corresponds to the checklist items. The dashed line indicates a PPR of 60%, which is the predefined threshold for importance.

Based on the IQD values, an in-depth analysis of the consensus measures revealed that a consensus was achieved for a total of 63 out of the 70 checklist items. Moreover, from PPR results, it is evident that within the subset of 63 items, 5 items exhibited a considerably low PPR, suggesting consensus that these items are not important. Therefore, these items were candidates for elimination from the checklist. Notably, two of these items, namely ‘previous experience with tES’ and ‘menstrual cycle status’, had mean ratings below 3, whereas the other three items, ‘alcohol consumption’, ‘caffeine consumption’ and ‘hours of sleep’, received mean ratings exceeding 3. Consequently, the decision based on the mean led to the exclusion of the former two items and the retention of the latter three.

For the seven items that garnered limited consensus, one item, ‘stimulator brand and model’, maintained a PPR exceeding 60% and was thus not removed from the checklist. From the remaining six items with low PPR, two items, ‘connectivity options’ and ‘stimulator control interface’, achieved a mean value below 3 and were omitted from the checklist. On the other hand, four items with larger mean ratings—‘current resolution’, ‘stimulator safety features’, ‘contact medium’ and ‘output channels’—were retained in the final checklist.

The final full version of the checklist comprises a total of 66 items, categorized into the five distinct domains: participants (12 items), stimulator (device, 9 items), electrodes (12 items), current (12 items) and procedure (25 items) (Supplementary Information, appendix A.1). The short version of the checklist comprises a total of 26 items, categorized into five distinct domains: participants (four items), stimulator/device (two items), electrodes (five items), current (eight items) and procedure (seven items) (Supplementary Information, appendix A.2). Detailed information about these checklist items is provided in the Supplementary Information, appendix B. To enhance the practical utility of these items, we provide the ‘RATES Table’ in the Supplementary Information, appendix C. This table provides a concise yet comprehensive overview of the checklist items, which can be used in future tES studies as a supplementary item to provide all relevant technical information. This presentation is suited not only to streamline review processes but also to pave the way for comprehensive comparisons of studies based on these criteria. Supplementary Information, appendix C also presents a showcase of the completed RATES table, capturing the characteristics of two studies through a retrospective lens. This illustrative section demonstrates a practical implementation of the RATES checklist. Cronbach’s α for the 70 items included in the initial round and for the 66 items included in the final checklist were 0.875 and 0.886, respectively. The Cronbach’s α for the short version, which includes 26 items, was 0.874. These values suggest a very good level of consensus achieved among the panelists during the evaluation process.

Discussion

The primary goal of the RATES study was to establish a comprehensive and consensus-based checklist for reporting and conducting tES studies. The lack of standardized reporting criteria has led to challenges in reproducibility, comparability and quality assessment across studies. This endeavor aimed to provide researchers, reviewers and readers with a reliable tool to evaluate and interpret tES research findings, fostering transparency, rigor and advancement of this promising field. Given the recommended scope for the Delphi panel size, which spans between 10 and 50 participants, the first round of this study included responses from 56 experts, indicating a response rate of 45.5%. Notably, attrition rates for the subsequent rounds were 11.2% and 5% for the second and third rounds, respectively. This sample size aligns well with the recommended range and shows strong consistency across successive rounds of the consensus process. The low level of attrition underscores the high level of engagement and interest among the expert participants.

The comprehensive evaluation of consensus measures and mean ratings provided a robust foundation for the final checklist, ensuring that it represents a well-established collective agreement among experts in the field. The amalgamation of two dimensions in the rating procedures—consensus and mean ratings—enabled a nuanced decision-making process that captured not only the level of agreement but also the perceived importance of each checklist item. The achievement of consensus for a substantial number of checklist items demonstrates the convergence of expert opinions on essential reporting components. Out of the 70 proposed items, 63 items garnered a strong consensus, reflecting the convergence of expert perspectives on what constitutes necessary or unnecessary information in tES studies. This accomplishment shows the success of this collaborative effort to establish a standardized framework for transparent and comprehensive reporting. Earlier studies found a similar consensus to control and report in TMS studies57. Together, the results of this study suggest the adequacy of the approach taken in establishing the RATES checklist, which aimed to systematically enhance reporting standards of tES studies.

The consensus outcomes achieved by the expert panel closely align with existing research evidence. Specifically, within the participant section, the relevance of demographic characteristics such as age65, gender66,67,68 and handedness69 in relation to the efficacy of tES has been shown. Clinical characteristics, encompassing medical history, psychiatric conditions and pertinent diagnoses, have a pivotal role in delineating and comprehending tES interventions70,71,72. Similarly, the effect of medication73,74, caffeine (cups in the last 12 h)75, nicotine76,77,78,79, alcohol80 and hours of sleep81 on tDCS effect has been described earlier. Other overarching sample characteristics, such as the recruitment process82, participant eligibility criteria83 and sample size84 have also been highlighted as important factors.

Regarding stimulator type, our comprehensive search of the literature did not yield any pertinent studies. Therefore, future investigations are warranted to explore the potential influence of stimulator attributes on the efficacy of tES interventions.

With respect to electrode parameters, the precise placement of stimulation electrodes is a fundamental factor in tES targeting4. Beyond positioning, electrode size85,86,87,88,89, inter-electrode distance86, electrode shape87,88, electrode orientation90, connector position87 and conductivities of different electrode materials and electrode to head interfaces (including saline solutions and electrode gel or cream)87,91 are crucial for the spatial distribution of the current density in tES.

Current intensity4,92,93, density94, distribution95, polarity4,21,22,96, frequency97,98, waveform99, amplitude100, stimulation duration4,20,93,101, state-dependency of stimulation effects13,102,103 and sham stimulation characteristics104 have been described as influential factors in tES studies.

Finally, the majority of procedure parameters included in the respective category are in accordance with the CONSORT guidelines105. For instance, the RATES ‘study design’ item mirrors the CONSORT recommendation for transparently describing the trial design, encompassing details such as randomization methods. Similarly, the RATES ‘session duration’ and ‘total number of sessions’ items closely correlate with CONSORT’s emphasis on detailing the duration and frequency of trial interventions, whereas ‘baseline assessment’ in RATES aligns with the CONSORT criterion of comprehensive baseline measurement reporting. ‘Randomization’ in RATES resembles the CONSORT focus on describing randomization processes and concealment methods. Ethical considerations, conflict of interest disclosure, and safety monitoring, as captured by RATES, are congruent with the CONSORT directives on ethical approval, transparency and participant safety reporting. The similarity between the RATES Procedure items and CONSORT guidelines emphasizes the comprehensive and organized design of the RATES checklist, contributing to clear, standardized and robust reporting of research methods.

The essential items retained in the Short RATES checklist capture the critical parameters necessary for ensuring transparency, reproducibility and interpretability of tES studies. Reporting participant characteristics such as demographic and clinical information ensures that individual differences influencing tES outcomes, including age, gender and medical history, are accounted for. These factors are integral for understanding response variability to stimulation and enable the results to be contextualized across diverse populations. In addition, parameters such as sample size and eligibility criteria are crucial for maintaining rigor and generalizability of findings, helping to avoid biases and ensuring sufficient statistical power to draw meaningful conclusions.

Beyond participant characteristics, the inclusion of stimulator specifications, electrode parameters and current settings emphasizes the importance of detailed technical descriptions in tES studies. For instance, reporting electrode positioning, size and montage, as well as current intensity, polarity and waveform, is critical for replicability and for understanding the spatial and functional targeting of stimulation. Similarly, procedural parameters such as study design, blinding and safety monitoring address both methodological transparency and participant safety, fostering trust in the reliability of results. Together, these essential items form the foundation of a standardized framework for reporting tES studies, facilitating cross-study comparisons, meta-analyses and overall advancements in the field.

The recommendations

The success of the RATES study in achieving consensus among experts, as reflected in the robust checklist developed, emphasizes the pivotal role of standardized reporting tools in advancing the rigor and quality of tES research. Considering these outcomes, the following recommendations aim to guide researchers, reviewers and practitioners in effectively implementing the RATES checklist and improving the overall methodological and reporting standards in the field of tES.

-

1.

Adoption of RATES checklist. Recommend that researchers in the field of tES adopt the RATES checklist as a standard tool for reporting and conducting their studies. Emphasize the importance of using a comprehensive and consensus-based checklist to enhance the transparency, comparability and reproducibility of tES research.

-

2.

Training on RATES implementation. Advocate for training programs and resources to educate researchers, reviewers and journal editors on the proper implementation of the RATES checklist. Provide guidance on how to integrate the checklist into study design, execution and reporting to ensure widespread adoption and adherence to standardized reporting criteria.

-

3.

Consideration of demographic and clinical characteristics. Stress the importance of carefully considering demographic and clinical characteristics of participants in tES studies. Recommend that researchers follow the checklist items related to participant information, taking into account factors such as age, gender, handedness, medical history, psychiatric conditions and relevant diagnoses.

-

4.

Exploration of stimulator attributes. Encourage researchers to explore the potential influence of stimulator attributes on the efficacy of tES interventions.

-

5.

Attention to electrode parameters. Advise researchers to pay careful attention to electrode parameters in their studies, including electrode size, interelectrode distance, shape, orientation, connector position and conductivities of different electrode materials. Emphasize the need for thorough consideration of these parameters for accurate targeting and spatial distribution of current density in tES.

-

6.

Consideration of influential factors. Encourage researchers to systematically consider and report on influential factors identified in the RATES study, such as current intensity, density, polarity, frequency, waveform, amplitude, stimulation duration, state-dependency of stimulation effects and sham stimulation characteristics. Suggest that researchers explore the effect of these factors on the outcomes of tES interventions.

-

7.

Continuous refinement and updates. Encourage a culture of continuous refinement and updates to the RATES checklist. Suggest that the checklist should be revisited and updated periodically to incorporate emerging evidence and address evolving challenges in tES research, ensuring its relevance and effectiveness over time.

Limitations and future directions

Although the RATES study offers a comprehensive and consensus-based checklist for enhancing reporting practice and conduction of tES studies, certain limitations should be acknowledged. The first limitation relates to the evolving nature of the field of tES, with new technologies and methodologies continuously emerging. As a result, checklist applicability to novel interventions or techniques that deviate from the currently established approaches might need to be assessed separately. Incorporating emerging technologies, novel interventions and refined methodologies into the checklist will enhance its applicability across a dynamic research landscape. Collaborative efforts involving researchers, clinicians and methodologists from various disciplines could contribute to further refinement and alignment of this checklist with the evolving state of the field. The checklist might benefit from periodic updates to ensure its relevance and comprehensiveness. Furthermore, we acknowledge the need for broader geographical diversity, particularly from underrepresented regions. Future iterations of the checklist should aim to recruit a more globally representative panel to strengthen its international relevance. Considering the global nature of tES research, future initiatives might strive to achieve an even more diverse panel of experts to ensure a broader representation of perspectives. Incorporating qualitative feedback from researchers who utilize the checklist in their studies might provide valuable insights into its practical implementation and effectiveness. This iterative feedback loop could inform future iterations of the checklist, making it more user-friendly and adaptable to the needs of researchers. Furthermore, a potential integration into academic journal submission and review processes could encourage widespread adoption and adherence to these reporting standards, further enhancing transparency and quality in tES research. Moreover, although our approach was thorough and systematic and we have provided resources for each item along with the respective changes during the Delphi rounds, we acknowledge that the initial list of items was not derived from a formal systematic review. Future iterations of the checklist may benefit from conducting such a review to further enhance the robustness and comprehensiveness of the included items. Finally, although preregistration might be somewhat less relevant for this consensus study than for original research studies and was not done for this specific project, it might nevertheless be useful to preregister also this type of study in future.

Conclusion

This study, driven by the pressing need for standardized reporting criteria in brain stimulation studies, aimed to create a comprehensive and consensus-based checklist to enhance transparency, comparability and quality assessment of tES studies. The alignment of consensus measures and mean ratings within the checklist development process ensured a sound approach for item inclusion. Out of the initially proposed 70 items, consensus was achieved for 66 items, signifying the convergence of expert perspectives on essential reporting components in tES studies. The integration of consensus and mean ratings led to the curation of a final checklist based on both agreement and perceived importance of respective items. Adaptation of this checklist for use in systematic reviews and meta-analyses might be relevant for enabling researchers to efficiently synthesize and compare tES studies.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study, including anonymized expert ratings across Delphi rounds and aggregated consensus metrics, are available via the following OSF repository at https://osf.io/q365u/?view_only=9705fc2155ec4bdd8727ac41a88749d2. The summary statistics used to generate figures and tables are provided in the Supplementary Information and source data files. No restrictions apply to data sharing. There are no proprietary datasets used in this study. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Sabé, M. et al. A century of research on neuromodulation interventions: a scientometric analysis of trends and knowledge maps. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 152, 105300 (2023).

Polanía, R., Nitsche, M. A. & Ruff, C. C. Studying and modifying brain function with non-invasive brain stimulation. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 174–187 (2018).

Kuo, M.-F., Chen, P.-S. & Nitsche, M. A. The application of tDCS for the treatment of psychiatric diseases. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 29, 146–167 (2017).

Nitsche, M. A. & Paulus, W. Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. J. Physiol. 527, 633–639 (2000).

Bikson, M. et al. Rigor and reproducibility in research with transcranial electrical stimulation: an NIMH-sponsored workshop. Brain Stimul. 11, 465–480 (2018).

Nitsche, M. A. et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation: state of the art 2008. Brain Stimul. 1, 206–223 (2008).

Varoli, E. et al. Tracking the effect of cathodal transcranial direct current stimulation on cortical excitability and connectivity by means of TMS-EEG. Front. Neurosci. 12, 319 (2018).

Jamil, A. et al. Systematic evaluation of the impact of stimulation intensity on neuroplastic after‐effects induced by transcranial direct current stimulation. J. Physiol. 595, 1273–1288 (2017).

Paulus, W. Transcranial electrical stimulation (tES–tDCS; tRNS, tACS) methods. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 21, 602–617 (2011).

Antal, A. & Paulus, W. Transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS). Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 317 (2013).

Antal, A. et al. Comparatively weak after-effects of transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) on cortical excitability in humans. Brain Stimul. 1, 97–105 (2008).

Fertonani, A. & Miniussi, C. Transcranial electrical stimulation: what we know and do not know about mechanisms. Neuroscientist 23, 109–123 (2017).

Carvalho, S. et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation based metaplasticity protocols in working memory. Brain Stimul. 8, 289–294 (2015).

Huang, Y., Thomas, C., Datta, A. & Parra, L. C. Optimized tDCS for targeting multiple brain regions: an integrated implementation. In 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 3545–3548 (IEEE, 2018).

Khorrampanah, M., Seyedarabi, H., Daneshvar, S. & Farhoudi, M. Optimization of montages and electric currents in tDCS. Comput. Biol. Med. 125, 103998 (2020).

Guler, S. et al. Optimization of focality and direction in dense electrode array transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). J. Neural Eng. 13, 36020 (2016).

Jog, M. V., Wang, D. J. J. & Narr, K. L. A review of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) for the individualized treatment of depressive symptoms. Pers. Med. Psychiatry 17, 17–22 (2019).

Esmaeilpour, Z. et al. Incomplete evidence that increasing current intensity of tDCS boosts outcomes. Brain Stimul. 11, 310–321 (2018).

Weller, S., Nitsche, M. A. & Plewnia, C. Enhancing cognitive control training with transcranial direct current stimulation: a systematic parameter study. Brain Stimul. 13, 1358–1369 (2020).

Vignaud, P., Mondino, M., Poulet, E., Palm, U. & Brunelin, J. Duration but not intensity influences transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) after-effects on cortical excitability. Neurophysiol. Clin. 48, 89–92 (2018).

Agboada, D., Mosayebi Samani, M., Jamil, A., Kuo, M.-F. & Nitsche, M. A. Expanding the parameter space of anodal transcranial direct current stimulation of the primary motor cortex. Sci. Rep. 9, 18185 (2019).

Mosayebi Samani, M., Agboada, D., Kuo, M. & Nitsche, M. A. Probing the relevance of repeated cathodal transcranial direct current stimulation over the primary motor cortex for prolongation of after‐effects. J. Physiol. 598, 805–816 (2020).

Jamil, A. & Nitsche, M. A. What effect does tDCS have on the brain? Basic physiology of tDCS. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Rep. 4, 331–340 (2017).

Mosayebi-Samani, M. et al. Transferability of cathodal tDCS effects from the primary motor to the prefrontal cortex: a multimodal TMS-EEG study. Brain Stimul. 16, 515–539 (2023).

Samani, M. M., Agboada, D., Jamil, A., Kuo, M.-F. & Nitsche, M. A. Titrating the neuroplastic effects of cathodal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) over the primary motor cortex. Cortex 119, 350–361 (2019).

Caulfield, K. A. & George, M. S. Optimized APPS-tDCS electrode position, size, and distance doubles the on-target stimulation magnitude in 3,000 electric field models. Sci. Rep. 12, 20116 (2022).

Im, C.-H., Jung, H.-H., Choi, J.-D., Lee, S. Y. & Jung, K.-Y. Determination of optimal electrode positions for transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Phys. Med. Biol. 53, N219 (2008).

Au, J., Karsten, C., Buschkuehl, M. & Jaeggi, S. M. Optimizing transcranial direct current stimulation protocols to promote long-term learning. J. Cogn. Enhanc. 1, 65–72 (2017).

Clenet, A. et al. Architecture and settings optimization procedure of a TES frequency domain multiplexed readout firmware. Exp. Astron. 38, 65–76 (2014).

Monte-Silva, K. et al. Dose-dependent inverted U-shaped effect of dopamine (D2-like) receptor activation on focal and nonfocal plasticity in humans. J. Neurosci. 29, 6124–6131 (2009).

Monte-Silva, K. et al. Induction of late LTP-like plasticity in the human motor cortex by repeated non-invasive brain stimulation. Brain Stimul. 6, 424–432 (2013).

Lorenz, R. et al. Efficiently searching through large tACS parameter spaces using closed-loop Bayesian optimization. Brain Stimul. 12, 1484–1489 (2019).

van Bueren, N. E. R. et al. Personalized brain stimulation for effective neurointervention across participants. PLoS Comput. Biol. 17, e1008886 (2021).

Woods, A. J. et al. A technical guide to tDCS, and related non-invasive brain stimulation tools. Clin. Neurophysiol. 127, 1031–1048 (2016).

Rostami, M., Golesorkhi, M. & Ekhtiari, H. Methodological dimensions of transcranial brain stimulation with the electrical current in human. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 4, 190 (2013).

Lefaucheur, J.-P. et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Clin. Neurophysiol. 128, 56–92 (2017).

Fregni, F. et al. Evidence-based guidelines and secondary meta-analysis for the use of transcranial direct current stimulation in neurological and psychiatric disorders. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 24, 256–313 (2021).

Bikson, M. et al. Transcranial electrical stimulation nomenclature. Brain Stimul. 12, 1349–1366 (2019).

Brunoni, A. R. et al. Clinical research with transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS): Challenges and future directions. Brain Stimul. 5, 175–195 (2012).

Olgiati, E. & Malhotra, P. A. Using non-invasive transcranial direct current stimulation for neglect and associated attentional deficits following stroke. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 32, 735–766 (2022).

Solomons, C. D. & Shanmugasundaram, V. Transcranial direct current stimulation: a review of electrode characteristics and materials. Med. Eng. Phys. 85, 63–74 (2020).

Moher, D., Jones, A., Lepage, L., Group, C. & Group, C. Use of the CONSORT statement and quality of reports of randomized trials: a comparative before-and-after evaluation. JAMA 285, 1992–1995 (2001).

Hopewell, S., Dutton, S., Yu, L.-M., Chan, A.-W. & Altman, D. G. The quality of reports of randomised trials in 2000 and 2006: comparative study of articles indexed in PubMed. BMJ 340, c723 (2010).

Plint, A. C. et al. Does the CONSORT checklist improve the quality of reports of randomised controlled trials? A systematic review. Med. J. Aust. 185, 263–267 (2006).

Turner, L., Shamseer, L., Altman, D. G., Schulz, K. F. & Moher, D. Does use of the CONSORT Statement impact the completeness of reporting of randomised controlled trials published in medical journals? A Cochrane review. Syst. Rev. 1, 1–7 (2012).

Hsu, C.-C. & Sandford, B. A. in Online Research Methods in Urban and Planning Studies: Design and Outcomes 173–192 (IGI Global, 2012).

Naisola-Ruiter, V. The Delphi technique: a tutorial. Res. Hosp. Manag. 12, 91–97 (2022).

Vernon, W. The Delphi technique: a review. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 16, 69–76 (2009).

Yousuf, M. I. Using expertsopinions through Delphi technique. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 12, 4 (2019).

Hasson, F., Keeney, S. & McKenna, H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J. Adv. Nurs. 32, 1008–1015 (2000).

Moher, D. et al. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Oncol. Res. Treat. 23, 597–602 (2000).

Sharma, A. et al. A consensus-based checklist for reporting of survey studies (CROSS). J. Gen. Intern. Med. 36, 3179–3187 (2021).

Ekhtiari, H. et al. A checklist for assessing the methodological quality of concurrent tES-fMRI studies (ContES checklist): a consensus study and statement. Nat. Protoc. 17, 596–617 (2022).

Ekhtiari, H. et al. A methodological checklist for fMRI drug cue reactivity studies: development and expert consensus. Nat. Protoc. 17, 567–595 (2022).

Ogden, S. R., Culp, W. C. Jr, Villamaria, F. J. & Ball, T. R. Developing a checklist: consensus via a modified Delphi technique. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 30, 855–858 (2016).

Kok-Pigge, A. C. et al. A Delphi consensus checklist helped assess the need to develop rapid guideline recommendations. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 156, 1–10 (2023).

Chipchase, L. et al. A checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies using transcranial magnetic stimulation to study the motor system: an international consensus study. Clin. Neurophysiol. 123, 1698–1704 (2012).

Pellegrini, M., Zoghi, M. & Jaberzadeh, S. A checklist to reduce response variability in studies using transcranial magnetic stimulation for assessment of corticospinal excitability: a systematic review of the literature. Brain Connect. 10, 53–71 (2020).

Peterchev, A. V. et al. Fundamentals of transcranial electric and magnetic stimulation dose: definition, selection, and reporting practices. Brain Stimul. 5, 435–453 (2012).

Antal, A. et al. Low intensity transcranial electric stimulation: safety, ethical, legal regulatory and application guidelines. Clin. Neurophysiol. 128, 1774–1809 (2017).

Rayens, M. K. & Hahn, E. J. Building consensus using the policy Delphi method. Policy, Polit. Nurs. Pract. 1, 308–315 (2000).

Raskin, M. S. The Delphi study in field instruction revisited: expert consensus on issues and research priorities. J. Soc. Work Educ. 30, 75–89 (1994).

Meijering, J. V., Kampen, J. K. & Tobi, H. Quantifying the development of agreement among experts in Delphi studies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 80, 1607–1614 (2013).

Greatorex, J. & Dexter, T. An accessible analytical approach for investigating what happens between the rounds of a Delphi study. J. Adv. Nurs. 32, 1016–1024 (2000).

Lloyd, D. M., Wittkopf, P. G., Arendsen, L. J. & Jones, A. K. P. Is transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) effective for the treatment of pain in fibromyalgia? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pain 21, 1085–1100 (2020).

Fehring, D. J. et al. Investigating the sex-dependent effects of prefrontal cortex stimulation on response execution and inhibition. Biol. Sex. Differ. 12, 1–15 (2021).

Licata, A. E. et al. Sex differences in effects of tDCS and language treatments on brain functional connectivity in primary progressive aphasia. NeuroImage Clin. 37, 103329 (2023).

Martin, A. K., Huang, J., Hunold, A. & Meinzer, M. Sex mediates the effects of high-definition transcranial direct current stimulation on ‘mind-reading’. Neuroscience 366, 84–94 (2017).

Kasuga, S. et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation enhances mu rhythm desynchronization during motor imagery that depends on handedness. Brain Cogn. 20, 453–468 (2015).

Nejati, V., Heyrani, R. & Nitsche, M. Attention bias modification through transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS): a review. Neurophysiol. Clin. 52, 341–353 (2022).

Sarkis, R. A., Kaur, N. & Camprodon, J. A. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS): modulation of executive function in health and disease. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Rep. 1, 74–85 (2014).

Nejati, V., Khorrami, A. S. & Fonoudi, M. Neuromodulation of facial emotion recognition in health and disease: a systematic review. Neurophysiol. Clin. 52, 183–201 (2022).

McLaren, M. E., Nissim, N. R. & Woods, A. J. The effects of medication use in transcranial direct current stimulation: a brief review. Brain Stimul. 11, 52–58 (2018).

Kuo, M.-F. & Nitsche, M. A. in Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation Neuropsychiatric Disorders Clinical Principals and Management (eds Brunoni, A. R., Nitsche, M. A. & Loo, C. K.) 729–740 (Springer, 2021).

Lattari, E. et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation combined with or without caffeine: effects on training volume and pain perception. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 94, 45–54 (2023).

Brunelin, J., Hasan, A., Haesebaert, F., Nitsche, M. A. & Poulet, E. Nicotine smoking prevents the effects of frontotemporal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in hallucinating patients with schizophrenia. Brain Stimul. 8, 1225–1227 (2015).

Grundey, J. et al. Neuroplasticity in cigarette smokers is altered under withdrawal and partially restituted by nicotine exposition. J. Neurosci. 32, 4156–4162 (2012).

Grundey, J. et al. Cortical excitability in smoking and not smoking individuals with and without nicotine. Psychopharmacology 229, 653–664 (2013).

Grundey, J. et al. Double dissociation of working memory and attentional processes in smokers and non-smokers with and without nicotine. Psychopharmacology 232, 2491–2501 (2015).

Bollen, Z., Dormal, V. & Maurage, P. How should transcranial direct current stimulation be used in populations with severe alcohol use disorder? A clinically oriented systematic review. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 53, 367–383 (2022).

Herrmann, O. et al. Sleep as a predictor of tDCS and language therapy outcomes. Sleep 45, zsab275 (2022).

Moseson, H., Kumar, S. & Juusola, J. L. Comparison of study samples recruited with virtual versus traditional recruitment methods. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 19, 100590 (2020).

Van Spall, H. G. C., Toren, A., Kiss, A. & Fowler, R. A. Eligibility criteria of randomized controlled trials published in high-impact general medical journals: a systematic sampling review. JAMA 297, 1233–1240 (2007).

Freiman, J. A., Chalmers, T. C., Smith, H. A. & Kuebler, R. R. in Medical Uses of Statistics (eds Bailar, J. C. & Mostelle, F.) 357–389 (CRC Press, 2019).

Laakso, I., Tanaka, S., Mikkonen, M., Koyama, S. & Hirata, A. Variability in TDCS electric fields: effects of electrode size and configuration. In 2017 XXXIInd General Assembly and Scientific Symposium of the International Union of Radio Science (URSI GASS) 1–4 (IEEE, 2017).

Faria, P., Hallett, M. & Miranda, P. C. A finite element analysis of the effect of electrode area and inter-electrode distance on the spatial distribution of the current density in tDCS. J. Neural Eng. 8, 66017 (2011).

Saturnino, G. B., Antunes, A. & Thielscher, A. On the importance of electrode parameters for shaping electric field patterns generated by tDCS. Neuroimage 120, 25–35 (2015).

Pancholi, U. & Dave, V. Variability of E-field in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex upon a change in electrode parameters in tDCS. In 2023 International Conference on Bio Signals, Images, and Instrumentation (ICBSII) 1–8 (IEEE, 2023).

Nitsche, M. A. et al. Shaping the effects of transcranial direct current stimulation of the human motor cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 97, 3109–3117 (2007).

Foerster, Á. et al. Effects of electrode angle-orientation on the impact of transcranial direct current stimulation on motor cortex excitability. Brain Stimul. 12, 263–266 (2019).

Palm, U. et al. The role of contact media at the skin-electrode interface during transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Brain Stimul. 7, 762–764 (2014).

Chew, T., Ho, K.-A. & Loo, C. K. Inter-and intra-individual variability in response to transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) at varying current intensities. Brain Stimul. 8, 1130–1137 (2015).

Nitsche, M. A. & Paulus, W. Sustained excitability elevations induced by transcranial DC motor cortex stimulation in humans. Neurology 57, 1899–1901 (2001).

Bastani, A. & Jaberzadeh, S. Differential modulation of corticospinal excitability by different current densities of anodal transcranial direct current stimulation. PLoS ONE 8, e72254 (2013).

Miranda, P. C., Lomarev, M. & Hallett, M. Modeling the current distribution during transcranial direct current stimulation. Clin. Neurophysiol. 117, 1623–1629 (2006).

Li, L. M. et al. Brain state and polarity dependent modulation of brain networks by transcranial direct current stimulation. Hum. Brain Mapp. 40, 904–915 (2019).

Pollok, B., Boysen, A.-C. & Krause, V. The effect of transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) at alpha and beta frequency on motor learning. Behav. Brain Res. 293, 234–240 (2015).

Polanía, R., Nitsche, M. A., Korman, C., Batsikadze, G. & Paulus, W. The importance of timing in segregated theta phase-coupling for cognitive performance. Curr. Biol. 22, 1314–1318 (2012).

Ali, M. M., Sellers, K. K. & Fröhlich, F. Transcranial alternating current stimulation modulates large-scale cortical network activity by network resonance. J. Neurosci. 33, 11262–11275 (2013).

Thiele, C., Zaehle, T., Haghikia, A. & Ruhnau, P. Amplitude modulated transcranial alternating current stimulation (AM-TACS) efficacy evaluation via phosphene induction. Sci. Rep. 11, 22245 (2021).

Nitsche, M. A. et al. Level of action of cathodal DC polarisation induced inhibition of the human motor cortex. Clin. Neurophysiol. 114, 600–604 (2003).

Masina, F. et al. State-dependent tDCS modulation of the somatomotor network: a MEG study. Clin. Neurophysiol. 142, 133–142 (2022).

Vergallito, A. et al. State dependent effectiveness of cathodal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Brain Stimul. 16, 239 (2023).

Fonteneau, C. et al. Sham tDCS: a hidden source of variability? Reflections for further blinded, controlled trials. Brain Stimul. 12, 668–673 (2019).

Bennett, J. A. The consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT): guidelines for reporting randomized trials. Nurs. Res. 54, 128–132 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the experts who generously contributed their time and insight throughout the Delphi process. Their thoughtful input and continued engagement were essential to the development of the RATES checklist.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.N. was responsible for conceptualization, analysis, writing of the original draft, and supervision. M.A.N. contributed to conceptualization and supervision. Z.V. handled visualization and data curation. The remaining authors participated as members of the expert panel and reviewed the manuscript across several rounds. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.A.N. is on the Scientific Advisory Boards of Neuroelectrics and Precisis and has conducted consulting activities for Boehringer Ingelheim. A.R.B. is on the Scientific Advisory board of Flow Neuroscience and on the Latin American Scientific Advisory Board of Livanova. He also received in-kind material support from MagVenture and Soterix. In the past 3 years, P.B.F. has received equipment for research from Neurosoft, Nexstim and Brainsway Ltd. He has served on Scientific Advisory Boards for Magstim and LivaNova and received speaker fees from Otsuka. He has also acted as a founder and board member for TMS Clinics Australia and Resonance Therapeutics. P.B.F. is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Investigator grant (grant no. 1193596). R.F. is a stakeholder of Newronika SpA, Milan, Italy. K.E.H. is a founder of Resonance Therapeutics. R.C.K. serves on the Scientific Advisory Boards of Neuroelectrics Inc. and Tech InnoSphere Engineering Ltd. and is a founder, director and shareholder of Cognite Neurotechnology Ltd. C.K.L. has served on an advisory board for Janssen and Douglas Pharmaceuticals and has received royalties as book editor from Springer Publishers. A.A. is a vice president of the European Society for Brain Stimulation and member at large at the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology, European, Middle European and Africa Chapter. She served as a paid consultant for NeuroConn, Ilmenau, Savir GmbH, Magdeburg, Germany and currently is a paid advisor by Pulvinar, USA. She is supported by the State of Lower Saxony, Germany (76251-12-7/19, ZN 3456), by the BMBF (STIMCODE) and DFG (AN 687/9-1, VIRON), EU-Horizon 2020 (PAINLESS). H.R.S. has received honoraria as speaker and consultant from Lundbeck AS, Denmark, and as editor (Neuroimage Clinical) from Elsevier Publishers, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. He has received royalties as book editor from Springer Publishers, Stuttgart, Germany, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, and from Gyldendal Publishers, Copenhagen, Denmark. H.R.S. was supported by a grand solutions grant ‘Precision Brain-Circuit Therapy - Precision-BCT’ from Innovation Funds Denmark (grant no. 9068-00025B) and a collaborative project grant ‘ADAptive and Precise Targeting of cortex-basal ganglia circuits in Parkinson’s Disease - ADAPT-PD’ from Lundbeckfonden (grant no. R336-2020-1035). J.B. is a board member of the NIBS section of the French Association of Biological Psychiatry and Neuropsychopharmacology (AFPBN) and of the European Society of Brain Stimulation (ESBS) and reports research grants in NIBS from CIHR (Canada), ANR and PHRC (France). M.S. is a board member of the German Association for Brain Stimulation in Psychiatry and in the field of brain stimulation, his local center for neuromodulation received for research purposes material from MagVenture, Deymed and NeuroConn/MAG and More. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Protocols thanks Xingbao Li and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Full and short versions of the RATES checklist, detailed item explanations, two sample completed checklists.

Source data

Source Data Figs. 1 and 2

Numerical source data of Figs. 1 and 2.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Nejati, V., Vaziri, Z., Antal, A. et al. Report Approval for Transcranial Electrical Stimulation (RATES): expert recommendation based on a Delphi consensus study. Nat Protoc (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-025-01259-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-025-01259-0