Abstract

The White Blood Cell (WBC) differential test ranks as the second most frequently performed diagnostic assay. It requires manual confirmation of the peripheral blood smear by experts to identify signs of abnormalities. Automated digital microscopy has emerged as a solution to reduce this labor-intensive process and improve efficiency. Several publicly available datasets provide various WBC subtypes of differing quality and resolution. These datasets have contributed to advancing WBC classification using machine learning techniques. However, digital microscopy of blood cells with high magnification often requires a wider depth of field, posing challenges for automatic digital microscopy that necessitates capturing multiple stacks of focal planes to obtain complete images of specific blood cells. Our dataset provides 25,773 image stacks from 72 patients. The image labels consist of 18 classes encompassing normal and abnormal cells, with two experts reviewing each label. Each image includes 10 z-stacks of cropped 200 by 200 pixel images, captured using a 50X microscope with 400 nm intervals. This study presents a comprehensive multi-focus dataset for WBC classification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The White Blood Cell (WBC) differential test is the second most commonly conducted hematological examination, providing crucial clinical insights1. It involves the manual enumeration of 200 WBCs by two experts using a peripheral blood smear stained with Romanowsky procedure2. However, this process is labor-intensive and time-consuming as the experts have to confirm each subtype of the WBCs manually3. Over the past few decades, automated digital microscopy, such as digital morphology analyzers, have been seamlessly integrated into laboratory systems, significantly enhancing operational efficiency4. Nonetheless, the verification and manual review process remains a necessity due to regulatory requirements and risk management in hematology laboratories3,5,6.

While machine learning research has successfully improved automated digital microscopy’s performance in terms of accuracy and efficiency7,8,9,10, significant improvements highly depend on the availability of large and high-quality datasets. Some authors developed and published on a small private dataset11,12. However, it has been claimed that the complexities of real-world data cannot be captured using the small datasets13. To address this, large-scale datasets for WBC classification have recently been published and made publicly available10,11,12,13,14, aiming to build more robust and generalized machine learning models. A summary comparing these datasets with our dataset is shown in Table 1. Some of the datasets were manually prepared and imaged11,12,13,14, while others, including ours10,15, were prepared and imaged automatically.

Although not highlighted by other works, high-magnification imaging using brightfield microscopy often results in a limited depth of field (DoF)16,17,18. Such a constraint can be challenging for automated digital microscopy because it takes multiple images in a z-stack to fully image a sample or cell. For example, a sample thickness of 3 to 4 requires at least seven focal planes for an axial step of 400 to 500 nm using a microscope with a DoF of 0.517. Multiple images are needed to fully reconstruct the image using fusion techniques16,17,19,20, which results in low throughput and increased data storage, and this may be problematic in automatic digital microscopy. As highlighted in Table 1, publicly available WBC classification datasets have limitations as they do not contain focal stack data, which could be useful in addressing the problems of limited depth of field (DoF) and multi-focus issues.

This paper presents the details of our newly released comprehensive, multi-focus dataset with granular labels for WBC classification. Our dataset contains 25,773 image stacks from 72 patients. The image labels consist of 18 classes encompassing normal and abnormal cells, with two experts reviewing all labels. This significant contribution aims to aid various research areas, primarily in improving classification models and focus stacking. With 10 z-stack images, researchers can leverage various techniques to fully utilize the information from each z-image. For example, our multi-focus dataset can help reduce labeling effort and mitigate human bias when using weakly supervised learning approaches21. Additionally, our dataset can be used to construct image fusion models based on machine learning17,19,20, test model robustness by simulating real application scenarios similar to the referenced study22, explore and research focus algorithms23,24,25,26, and augment model training with techniques akin to defocus blur augmentation, which is known to produce more robust models compared to those without augmentation27,28,29,30.

Methods

Peripheral blood samples were collected from 72 Asan Medical Center (AMC) patients in Seoul, Republic of Korea (Institutional Review Board approval number: S2019-2564-0004). These blood samples were stored in ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA) tubes. Residual samples after testing were used to prepare the dataset. Due to this condition, the IRB was exempted from obtaining written informed consent, as the blood samples did not contain identifiable personal information. Consequently, since identifiable personal information was not included, we were able to retrieve normal and abnormal cases based on WBC classes only. As shown in Table 2, 57 samples contained abnormal WBCs, while 15 samples only contained normal WBCs.

Sample preparation, which included smearing and staining, was performed using miLab, a fully automated staining and digital imaging platform developed by Noul, Co., Ltd.31. A drop of 4 to 5 microliters of whole blood was inserted into the cartridge, equipped with a thin plastic film for smearing. After smearing, the blood cells were fixed, and the blood film was stained using a newly developed hydrogel-based staining method incorporated into the cartridge32. From 72 whole blood samples, a total of 214 slides were prepared to acquire the data (Table 2).

Data acquisition

Images were captured using miLab, which features a motorized stage, a 50X lens, and a digital camera. When a stained blood smear was ready for imaging, the device initiated imaging of fields containing white blood cells. The motorized stage moved until the camera detected one WBC. Once the WBC was detected, a stack of ten multi-focus images was acquired with a step interval of approximately 400. The device continued capturing WBCs until a specific count was reached.

Data annotation

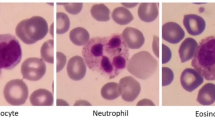

Figure 1 schematically describes the processing data for annotation. Each field of view (FoV) that contains WBCs was imaged for ten z-stacks using miLab. As a result, the information on bounding boxes was included to locate the WBCs. Each bounding box was used to crop the z-stack images. After cropping a stack of 10 images, they were concatenated to form a single image for the annotation. Two medical technologists primarily participated in determining the WBC subtype by examining all z-stack images guided by the Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)2. Initially, a medical technologist with approximately two years of experience at a university hospital identified the WBC subtypes. Subsequently, these annotations were reviewed by a technologist with around 16 years of experience. In cases of disagreement, the cells were reexamined by additional experts with over 20 years of experience. If there was no agreement, the remaining cells were evaluated by additional experts with over 20 years of experience. The image was excluded from annotation if the stain quality was deemed too poor or the bounding box extraction was not appropriate for confirmation.

The process of multi-focus image data acquisition. A stack of 10 images is captured, and a U-net-based segmentation model is used on the best-focus image determined by the Laplacian filter. Then, the bounding box is extracted to find the location of the WBC. Experts examine all z-stacks to confirm the subtype.

Data Records

The dataset is publicly available on the figshare data repository15. It is comprised of 257,730 cropped WBC images (10 times 25,773 images) and two CSV files (“labels.csv” and “slide_number.csv”). Each image has a cropped size of 200 × 200 pixels. The image name is formatted with the stack number. For example, “100_4.jpg” refers to cell image number 100 with a z-stack number of 4. Z-stack images range from 0 to 9. The CSV file called “labels.csv” contains bounding box locations within the cropped images and WBC subtype labels for each image crop in the same folder. Each row of the CSV file includes the image name, top-left x and y coordinates of the bounding box, width and height of the bounding box, and a WBC subtype label. The second CSV file, called “slide_number.csv”, contains the slide number associated with each cell image. It lists the image number alongside the slide number from which the cell was obtained, with each slide containing multiple cells. There are 214 slides as shown in Table 2.

The dataset contains 18 classes, including segmented neutrophil, banded neutrophil, eosinophil, basophil, lymphocyte, monocyte, abnormal lymphocyte, metamyelocyte, myelocyte, promyelocyte, blast, immature WBCs, giant platelet, aggregated platelet, smudge, broken cell, nucleated red blood cell, unknown WBC, and artifact. The detailed statistics of the dataset are listed in Table 3.

Additional sets of images and CSV files are provided to help readers reproduce the technical validation related to Fig. 2. These resources are located in a folder named “validation”. These include label files similar to those in the open dataset; however, the labels are only available for WBC subtypes such as Neutrophil, Lymphocyte, Basophil, Monocyte, Eosinophil, and Others. Additionally, a CSV file named “cbc_result.csv” is included, which provides the ground truth described in the Technical Validation section.

Calculated R2 scores between miLab expert classification and manual microscope are shown. Five normal WBC subtypes (neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte, eosinophil, basophil) and other immature WBCs are listed. The x-axis corresponds to the percentage of WBC cells of a specific subtype that exist in a ground truth slide. The y-axis represents the percentage of WBCs that miLab detected and classified by our experts. The axes are in logarithmic scale to better visualize data points.

Technical Validation

Technical validation of our dataset consists of two components. In the first component we demonstrate that the distribution of miLab expert classifications corresponds to the distribution of cells that are provided by AMC as the ground truth. This validates our method by showing that the slides and annotation quality, including miLab preparation and expert classification, correspond to the slides and ground truth provided by the gold standard method employed at the hospital. In the second component we verify the accuracy of our labels by training a classification model using our dataset and re-examining the labels of the misclassified images.

To validate the annotation quality of the dataset, we obtained 40 additional blood samples from AMC which are not included in the main dataset. The ground truth for the distribution of WBC subtypes was provided by AMC. Samples underwent a Complete Blood Count (CBC) using XN-Series (XN-20, Sysmex, Kobe, Japan). Then, additional manual differential counts were conducted if any flags appeared. These manual differential counts followed the guidelines provided by CLSI2. The cell types included were Blast, Myelocyte, Metamyelocyte, Band neutrophil, Segmented neutrophil, Lymphocyte, Monocyte, Eosinophil, Basophil, Neoplastic lymphocyte, Reactive lymphocyte, Atypical lymphocyte, and nRBC. Certain cell types were combined for analysis; for example, Band neutrophil and Segmented neutrophil were grouped as Neutrophil. Additionally, Blast, Myelocyte, Metamyelocyte, Neoplastic lymphocyte, Reactive lymphocyte, and Atypical lymphocyte were grouped together as Others.

Using the same blood samples, we then automatically smeared, stained and detected WBCs using miLab. The detected cells were then classified by our two experts and the distribution of the outputs was compared to the ground truth from AMC. Figure 2 shows that the miLab prepared slide with expert classification and manual microscopic ground truth from AMC generally provide a high correlation (R2 > 0.9). However, we notice that monocytes and basophils provide lower values of 0.836 and 0.428 respectively. The low correlation coefficient for Basophils is likely due to the low number of basophils in each sample. For monocytes we currently have no intuition as to why the correlation is lower; however we have observed that the same general trend exists in other published papers33,34.

A classification model using just one best-focused image per cell was developed to confirm the whole labeling correctness. The best-focused image was selected from a stack of 10 images using an edge filter using variance similar to Laplacian filter35 because we assumed an image would be best viewed if its edge was strengthened. Each input WBC was cropped from the context image and upsampled to a size of 200 × 200. Therefore, the resized ratio was also used as an input feature. The dataset was randomly split into a training, valid, and test set with a ratio of 70%, 20%, and 10% respectively, and a fine-tuned ResNet34 model yielded an acceptable test accuracy of over 90%. To double check the label accuracy of the data, we then used our trained model to find difficult examples and re-examined them with our domain experts to ensure that they were not mislabeled.

The experiments on label correctness observed several common misclassifications when a single focused image per cell was evaluated. Specifically, the model needed clarification for the following classes. First, some cells classified in immature WBCs tended to be highly confused with those in blasts.We found that there was a some confusion in classifying between immature WBCs and blasts. Additionally, we found a high confusion rate between lymphocytes and variant lymphocytes. Finally, we observed some confusion between neutrophils, metamyelocytes and myelocytes. Interestingly, mistakes that junior microscopists tend to make are similar.

Usage Notes

The dataset consists of images in the JPEG format and label files in the CSV format. As such, no special software is required to use this dataset. Including fine-grained classes, labels allow the dataset’s reformulation to fit the user’s specific needs. See Table 3 for the list of available classes. The multiple stacks of focal planes for WBC might help improve classification performance in machine learning.

Code availability

We offer a codebase designed for extracting bounding boxes from data obtained through miLab. In addition, we provide a collection of stack images and a sample CSV file. These resources serve to illustrate the process of generating stacked images for annotation, leveraging exclusively the metadata provided. While the code demonstrates preprocessing using a sample case, it closely resembles the approach we employed. A sample code that computes the best focus based on Laplacian operator is also provided in the repository. You can find the code repository at the following link: https://github.com/seongjinpark34/multi-focus-wbc-dataset.

References

Stouten, K., Riedl, J. A., Levin, M.-D. & Van Gelder, W. Examination of peripheral blood smears: Performance evaluation of a digital microscope system using a large-scale leukocyte database. International Journal of Laboratory Hematology 37, e137–e140, https://doi.org/10.1111/ijlh.12391 (2015).

Koepke, J. A. Reference Leukocyte (WBC) Differential Count (Proportional) and Evaluation of Instrumental Methods (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, Pa., 2007), 2nd ed edn.

Nam, M. et al. Digital Morphology Analyzer Sysmex DI-60 vs. Manual Counting for White Blood Cell Differentials in Leukopenic Samples: A Comparative Assessment of Risk and Turnaround Time. Annals of Laboratory Medicine 42, 398–405, https://doi.org/10.3343/alm.2022.42.4.398 (2022).

Yoon, S. et al. Performance of digital morphology analyzer Vision Pro on white blood cell differentials. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM) 59, 1099–1106, https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2020-1701 (2021).

Yoon, S. & Kim, H. R. Analytical performance of the digital morphology analyzer Sysmex DI-60 for body fluid cell differential counts. PLOS ONE 18, e0288551, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288551 (2023).

Njoroge, S. W. & Nichols, J. H. Risk Management in the Clinical Laboratory. Annals of Laboratory Medicine 34, 274–278, https://doi.org/10.3343/alm.2014.34.4.274 (2014).

Yao, J. et al. High-Efficiency Classification of White Blood Cells Based on Object Detection. Journal of Healthcare Engineering 2021, 1615192, https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/1615192 (2021).

Dong, N., Zhai, M.-d, Chang, J.-f & Wu, C.-h A self-adaptive approach for white blood cell classification towards point-of-care testing. Applied Soft Computing 111, 107709, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2021.107709 (2021).

Boldú, L., Merino, A., Acevedo, A., Molina, A. & Rodellar, J. A deep learning model (ALNet) for the diagnosis of acute leukaemia lineage using peripheral blood cell images. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 202, 105999, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.105999 (2021).

Acevedo, A. et al. A dataset of microscopic peripheral blood cell images for development of automatic recognition systems. Data in Brief 30, 105474, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2020.105474 (2020).

Li, M. et al. A deep learning model for detection of leukocytes under various interference factors. Scientific Reports 13, 2160, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29331-3 (2023).

Yao, X., Sun, K., Bu, X., Zhao, C. & Jin, Y. Classification of white blood cells using weighted optimized deformable convolutional neural networks. Artificial Cells, Nanomedicine, and Biotechnology 49, 147–155, https://doi.org/10.1080/21691401.2021.1879823 (2021).

Bodzas, A., Kodytek, P. & Zidek, J. A high-resolution large-scale dataset of pathological and normal white blood cells. Scientific Data 10, 466, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02378-7 (2023).

Kouzehkanan, Z. M. et al. A large dataset of white blood cells containing cell locations and types, along with segmented nuclei and cytoplasm. Scientific Reports 12, 1123, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04426-x (2022).

Park, S. et al. A Large Multi-Focus Dataset for White Blood Cell Classification, Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6844605 (2024).

Liu, S. & Hua, H. Extended depth-of-field microscopic imaging with a variable focus microscope objective. Optics Express 19, 353–362, https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.19.000353 (2011).

Manescu, P. et al. Content aware multi-focus image fusion for high-magnification blood film microscopy. Biomedical Optics Express 13, 1005–1016, https://doi.org/10.1364/BOE.448280 (2022).

Forster, B., Van De Ville, D., Berent, J., Sage, D. & Unser, M. Complex wavelets for extended depth-of-field: A new method for the fusion of multichannel microscopy images. Microscopy Research and Technique 65, 33–42, https://doi.org/10.1002/jemt.20092 (2004).

Liu, Y., Wang, L., Li, H. & Chen, X. Multi-focus image fusion with deep residual learning and focus property detection. Information Fusion 86–87, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2022.06.001 (2022).

Kausar, N., Majid, A. & Javed, S. G. Developing learning based intelligent fusion for deblurring confocal microscopic images. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 55, 339–352, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2016.08.006 (2016).

Dehghani, S., Busam, B., Navab, N. & Nasseri, A. BFS-Net: Weakly Supervised Cell Instance Segmentation from Bright-Field Microscopy Z-Stacks https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2206.04558 (2022).

Loddo, A. & Putzu, L. On the Effectiveness of Leukocytes Classification Methods in a Real Application Scenario. AI 2, 394–412, https://doi.org/10.3390/ai2030025 (2021).

Zhang, J. & Zhang, T. Focusing Algorithm of Automatic Control Microscope Based on Digital Image Processing. Journal of Sensors 2021, 5643054, https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5643054 (2021).

Dastidar, T. R. Automated Focus Distance Estimation for Digital Microscopy Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), 1049–1056, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPRW.2019.00137 (IEEE, Long Beach, CA, USA, 2019).

Liao, J. et al. Deep learning-based single-shot autofocus method for digital microscopy. Biomedical Optics Express 13, 314, https://doi.org/10.1364/BOE.446928 (2022).

Yazdanfar, S. et al. Simple and robust image-based autofocusing for digital microscopy. Optics Express 16, 8670, https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.16.008670 (2008).

Mazilu, I. et al. Defocus Blur Synthesis and Deblurring via Interpolation and Extrapolation in Latent Space. In Tsapatsoulis, N. et al. (eds.) Computer Analysis of Images and Patterns, vol. 14185, 201–211, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-44240-7_20 (Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 2023).

Lébl, M., Šroubek, F. & Flusser, J. Impact of Image Blur on Classification and Augmentation of Deep Convolutional Networks. In Gade, R., Felsberg, M. & Kämäräinen, J.-K. (eds.) Image Analysis, vol. 13886, 108–117, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31438-4_8 (Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 2023).

Yoshihara, S., Fukiage, T. & Nishida, S. Does training with blurred images bring convolutional neural networks closer to humans with respect to robust object recognition and internal representations. Frontiers in Psychology 14, 1047694, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1047694 (2023).

Bujimalla, S., Subedar, M. & Tickoo, O. Data augmentation to improve robustness of image captioning solutions (2021).

Bae, C. Y. et al. Embedded-deep-learning-based sample-to-answer device for on-site malaria diagnosis. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 12, 1392269, https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2024.1392269 (2024).

Choi, J.-H. et al. Hydrogel-Based Stamping Technology for Solution-Free Blood Cell Staining. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 13, 22124–22130, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.0c22521 (2021).

Tabe, Y. et al. Performance evaluation of the digital cell imaging analyzer DI-60 integrated into the fully automated Sysmex XN hematology analyzer system. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM) 53, https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2014-0445 (2015).

Ceelie, H., Dinkelaar, R. B. & Van Gelder, W. Examination of peripheral blood films using automated microscopy; evaluation of Diffmaster Octavia and Cellavision DM96. Journal of Clinical Pathology 60, 72–79, https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2005.035402 (2007).

Torre, V. & Poggio, T. A. On Edge Detection. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence PAMI-8, 147–163, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.1986.4767769 (1986).

Acknowledgements

We thank Daeseon Jeong, Dongshik Ham, Jinhyoung Park, and Minjong Kim for providing us with technical and moral support throughout the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: processing data and generating codes: S. Park, A. Balint; design and validate technically: S. Park, H. Cho, B.M. Woo, S.M. Lee; data collection: B.M. Woo, S.M. Lee, D. Bae, Y.J. Seo, and C.Y. Bae; manage protocols: B.M. Woo, K. Choi. All authors prepared and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Kyu-Hwan Jung receives a consulting fee from Noul Co., Ltd. There are no other conflicts of interest for other authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, S., Cho, H., Woo, B.M. et al. A large multi-focus dataset for white blood cell classification. Sci Data 11, 1106 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03938-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03938-1

This article is cited by

-

A large dataset of bone marrow cells in myelodysplastic syndrome for classification systems

Scientific Data (2025)