Abstract

Faced with heterogeneity of healthcare data, we propose a novel approach for harmonizing data elements (i.e., attributes) across health data standards. This approach focuses on the implicit concept that is represented by a data element. The process includes the following steps: identifying concepts, clustering similar concepts and constructing mappings between the clusters using the Simple Standard for Sharing Ontological Mappings (SSSOM) and Resource Description Framework (RDF), and enabling the creation of reusable mappings. As proof-of-concept, we applied the approach to five common health data standards - HL7 FHIR, OMOP, CDISC, Phenopackets, and openEHR, across four domains, such as demographics and diagnoses, and nine topics within those domains, such as gender and vital status. These domains and topics are selected to represent the broader range of topics in the health field. For each topic, data elements were found in the health data standards after a thorough search, resulting in the analysis of 64 data elements, identification of their underlying concepts, and development of mappings. Three use cases were implemented to demonstrate the role of data element concepts in data harmonization and data querying at varying levels of granularity. The approach helps overcome the limitations of context-dependent mappings and provides valuable insight for mapping practice within the health domain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The digital transformation of healthcare1 has generated a vast virtual repository of health data dispersed across databases in varied health data standards within numerous healthcare organizations. Using this heterogeneous data pool enables comprehensive insights from diverse populations, thereby accelerating the development of accurate diagnoses and the formulation of novel treatments2. The emerging paradigm of federated analysis offers a promising way to leverage these dispersed data with less risk of compromising on patient privacy or data security3,4,5. However, the path to accomplishing seamless integration, either centralized or federated, is full of obstacles. First among them are syntactic and semantic heterogeneity of data originating from various health data standards, which prevent automated interpretation of the semantics of data. This in turn impedes the exchange of data and the acquisition of meaningful insights from these data in a semantic manner6.

To enable data exchange across standards, many researchers have focused on the field of ‘mappings’7,8,9,10. In the context of this research, we consider mapping as the process, or the result thereof, of defining ordered pairs of data elements as equivalent, broader, narrower, or related11. However, currently mappings are context-dependent while the context is often unknown or not made explicit, and hence reusability is limited. For example, the distinction between ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ in different standards must be carefully considered. For instance, HL7 FHIR12 uses the element ‘Patient.gender’ (https://www.hl7.org/fhir/patient-definitions.html#Patient.gender) to represent a patient’s administrative gender, such as male or female, for record keeping purposes. Meanwhile, CDISC13 uses ‘SEX’ to refer specifically to the biological sex of a clinical trial participant. While sex and gender are often used interchangeably with minimal error in the general population14,15, misalignment in contexts like clinical trials or transgender care could result in erroneous data analysis16. A mapping that equates ‘gender’ in FHIR with ‘sex’ in CDISC may work in one context, such as general patient management, but would be inappropriate in research settings that require accurate biological sex data for meeting regulatory requirements and organizing trial participants. Besides, a data element should have and be described by both semantic and representational components according to the ISO/IEC 11179:202317. For example, the data element concept ‘date of birth’ is the specific date when an individual was born; two representations might exist, one represented as SNOMEDCT:184099003 with a value in the format ‘YYYY-MM-DD’ (e.g., 1995-01-11), conforming to the ISO 8601 standard for value representation, and one represented as LOINC:21112-8 with a value in the format that allows for alphanumeric characters such as ‘1995, January 11th’ with additional constraints such as not allowing the date to be in the future. While there is often too much focus on the representational level, the mapping should take place at the semantic level and rely on the ‘data-element concept’, which is often implicit. Such disregard of the ‘data-element concept’ in practice (which captures the real-world concept) imposes the necessity of making the semantics of data elements explicit, which is essential for reusable mappings. While the values of data elements (i.e., value domain) are often based on explicit representations using well-established vocabularies, data elements themselves are often only provided with free-text descriptions or simply labels.

To solve the problem of mappings that cannot be reused, we propose using generic concepts to harmonize different data elements. Aligning the underlying concepts of these data elements facilitates mapping between them and the harmonization of a broader range of data elements. For example, by defining a concept for ‘diagnosis record’, we can cover both ‘condition_occurrence_id’ in OMOP and ‘Problem/Diagnosis’ in openEHR. However, if we define a concept for ‘condition occurrence’, it would only cover ‘condition_occurrence_id’ because the openEHR ‘Problem/Diagnosis’ concept is broader, encompassing both clinical diagnoses and patient-reported conditions. The data-element concepts allow consistent interpretation and integration across various systems. In this paper, we introduce the workflow of this mapping approach and demonstrate the approach with a small-scale implementation that enables data querying from diverse resources and at various levels of granularity. Through this, we highlight the role of the semantics of data elements in data integration in a reusable manner and the potential for broader applicability across various health data standards.

Methods

This section introduces the rationale of our concept-based approach, emphasizing the relationship between concepts and representations, along with the SSSOM framework that supports the workflow. We then describe the health data standards that will be applied within this workflow to create mappings and define the scope of the study. Lastly, we introduce the use cases that will be utilized to test these mappings and demonstrate the practical application of the approach.

ISO/IEC 11179 for concept and representation

The international standard, ISO/IEC 11179:202317, provides guidelines and procedures for the semantics and representation of data elements. Central to this standard is the ‘data element’ entity - a unit of data for which the definition, representations, and permissible values can be specified - and that one data element has both semantic and representational components (see Fig. 1).

The conceptual model of the ISO/IEC 11179 Metadata Registry (MDR) with semantic and representational components, adjusted from17. a) describes the generic components of the model, b) presents an example thereof.

A data element concept refers to the meaning or semantics of a data element. It is an abstract, semantic understanding of the data element. It typically answers questions like: ‘what real-world concept is supposed to be captured in the data element?’ and ‘what is the definition for the concept?’. For example, the data element FHIR:Observation.code.LOINC#3141-9 is supposed to capture the real-world concept ‘body weight`, the definition of which could be ‘the mass or weight of a person’. A data element, i.e., the representation, on the other hand, is about how the concept is concretely captured in a system that is often based on a health data standard. Terminology (i.e., the use of external ontological terms) and designation (i.e., the name or label for a concept) are two example attributes of a data element at the representational level that are different across health data standards.

SSSOM mapping framework

The Simple Standard for Sharing Ontological Mappings (SSSOM)18 is a standard for representing semantic mappings between information entities. SSSOM aims to to facilitate the exchange and integration of semantic entity mappings.

In this context, a mapping is defined as a statement <s, p, o> that uses a predicate (p) to establish a correspondence between a subject entity (s) and an object entity (o). This pattern aligns with the Resource Description Framework (RDF)19, which specifies that data should be represented as triples consisting of subject, predicate, and object. Figure 2 shows an example mapping in RDF describing that the data element representing sex defined by the National Institutes of Health is broader than the phenotypic sex defined by the National Health Service.

To facilitate the reusability of mappings, the SSSOM framework includes additional metadata for describing the mappings, such as author, mappings justification, mappings rules.

Health data standards

The following five health data standards were selected because they are commonly used:

-

Health Level Seven(HL7) Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR)12 - a standard developed by HL7 for the exchange of electronic health record data. It provides a comprehensive framework and related standards for the representation of health information in a way that is suitable for use in modern apps, services, and software.

-

Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC) Study Data Tabulation Model (SDTM)13 - a set of standards for organizing and formatting clinical trial data for regulatory submissions, ensuring consistent and interpretable data across studies.

-

The Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) Common Data Model (CDM)20 - a standardized data model that allows for the systematic analysis of disparate observational databases. It facilitates the harmonization of data from diverse sources, enabling researchers to generate consistent and reproducible results.

-

openEHR21 - an open standard for the representation of health information, focusing on the support and creation of electronic health records. It provides a platform-independent model, allowing for the flexible representation and retrieval of health data.

-

Phenopackets22 - a standard format designed for the representation of phenotypic information. It facilitates the sharing of structured phenotype data and streamlines the integration of genetic and phenotypic data.

These health data standards aim to make health data more structured and interoperable, each with a specific focus. CDISC SDTM organizes clinical trial data for regulatory consistency, while HL7 FHIR facilitates data exchange between health systems. OMOP CDM standardizes observational data for systematic analysis, openEHR supports flexible electronic health records, and Phenopackets provide a structured format for integrating genetic and phenotypic information.

Four domains - Demographics, Diagnoses, Measurements, and Medications - are selected, see Table 1. These domains are selected because they capture the common aspects of patient information, clinical practice, and medical treatment, and are among the common domains across health data standards that were designed with different focuses and purposes. Furthermore, the topics within these domains were selected to reflect different types of values, including dates, numbers, and categorical values. In each domain, one or more topics are chosen as the starting point to include data elements that are potentially relevant to the topic based on the description of the data element (see Supplementary Table 1).

Use cases

To demonstrate the usefulness of the mappings created by utilizing concepts, we conducted the following data queries for three types of use cases in the Sex topic:

-

Get patients with a specific data element

-

Get all the patients who have any data element regarding ‘sex’ with any value registered.

-

Get all the patients who have a value for ‘biological sex’ registered.

-

Get all the patients who have a value for ‘gender’ registered.

-

-

Get patients with specific values

-

Get all patients whose ‘sex’ is female.

-

-

Get the distribution

-

Get the types of ‘sex’ and their distribution.

-

For the purpose of proof-of-concept, we created a synthetic dataset for the demonstration and simplified the data structure of the dataset, using punning23. For example, an instance of a FHIR patient that has birth sex as male, can be represented as:

Subject: FHIR:Patient01

Predicate: FHIR:BirthSex

Object: http://terminology.hl7.org/CodeSystem/v3-AdministrativeGender#M

While FHIR:BirthSex is defined as a class, not as a property, for the purpose of readability in this proof of concept, we use it as a predicate. Similarly, male administrative gender is strictly speaking a class, but in this example it is regarded an instance.

Twenty synthetic patient records were created for the use cases to be answered by querying. Synthetic data, SPARQL queries, and the Python codes executing the queries are all available on GitHub24.

Results

In this section, we begin by providing a detailed explanation of the concept-based approach. Following that, we illustrate how this approach can be applied to generate semantic mappings across the five previously introduced health data standards. Lastly, we present the outcomes of employing these mappings in data querying.

Concept-based approach

In this sub-section, we describe the concept-based approach, which consists of: (1) determination of domains and topics within them; (2) inventory of representations; (3) collection of semantics-reflecting content; (4) determination of concepts; (5) creation of concept clusters; and (6) construction of SSSOM mappings.

Determine domains and topics

Considering the extent and complexity of healthcare data, the first step is to select domains that are characteristic for health data, e.g., Demographics, Measurements. Each domain includes multiple topics referring to distinct health data. Example topics are date of birth in the Demographics domain and heart rate in the Measurements domain.

Inventory of representations

For each topic, we made an inventory of potentially relevant data elements from each of the data standards. For example, we utilize the definition from the World Health Organization, ‘sex refers to the biological characteristics that define humans as female or male’, for the Sex topic. Based on this definition, we searched health data standards for relevant data elements; e.g., the US-CORE-BirthSex data element is a representation of ‘sex’ in HL7 FHIR (or FHIR:BirthSex), while the data element Patient.gender is a representation of ‘gender’. When the value domain (i.e., the value) of a data element is a categorical value such as ‘male’ and ‘female’, these values were processed in the same way as data elements.

Collect information on concepts

We searched the documentation of the chosen health data standards for the definition, comment, or any text that can reflect the concept of the data element (i.e., semantics-reflecting content) and utilized them to determine the data-element concept (i.e., the concept). For example, the definition of FHIR:BirthSex is lacking but a text summary is provided: ‘a code classifying the person’s sex assigned at birth as specified by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC)’. Since the text summary implicitly reflects the meaning of the data element, it is recorded as the semantics-reflecting content of the FHIR:BirthSex element.

Determine concepts

We determined the concepts by integrating all the information sources found in the previous step, to formulate free texts for better readability and comparison. When terminology bindings are provided, the bound terms are also considered during the concept formulation. For example, there are two pieces of semantics-reflecting content of FHIR:BirthSex: one from text summary (as discussed in the previous step) and another from LOINC:76689-9, a representation suggested in the US-CORE specification. After synthesizing these sources, the concept can be articulated as ‘the sex of a person at birth (and recorded on the birth certificate)’.

Create concept clusters

We created concept clusters to include all concepts relevant to a specific topic, thereby stratifying the concepts. A cluster represents a higher-level concept that describes the relationships between individual concepts. Each cluster may encompass one or more concepts, but collectively, the clusters should cover all identified concepts. For example, consider three concepts: (1) ‘the sex of a person at birth’, (2) ‘the biological sex of a patient’, and (3) ‘the biological sex of a person’. These can be grouped into two clusters: ‘the sex of a person’, which includes concepts (1) and (3), and ‘the sex of a patient’, which covers the concept (2), with the distinguishing point being the different subjects involved.

Build SSSOM mappings

We constructed mappings between the data elements based on the concept clusters and represented them in RDF according to the SSSOM mapping standard. The connections between data elements and their categorical values are expressed using the predicate ‘sio: SIO_000217‘ (has quality) from the Semanticscience Integrated Ontology (SIO)25.

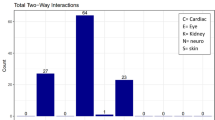

Concepts and representations

For the nine topics, we identified 64 data elements in the five health data standards (i.e., HL7 FHIR, CDISC, OMOP, openEHR, and Phenopackets), as shown in Table 2. Most topics have at least one data element in each standard except for gender, severity and vital status where some data elements are not represented. These 64 data elements represent a thorough and exhaustive set for the nine topics, as they were identified by systematically searching all five health data standards for relevant information. The following sections provide more details by topic, except for Sex and Gender, which are discussed together because they are often confused26 or wrongly considered interchangeable. For each topic we go through steps 2, 3, 4 and 5 of the approach by describing how the relevant representations were inventorized, how the information on concepts were collected, how the concepts were determined and clustered.

Sex and gender

In the five health data standards, seven data elements concerning the Sex topic and four data elements concerning the Gender topic were identified, see their representations, and terminology, and concepts in Table 3. For example, CDISC.SDTM.SEX is the representation of the concept ‘the physical difference between male and female of a subject’, and is bound to NCIT:C66731.

Based on the concept descriptions in Table 3, five concept clusters were specified to stratify the concepts: ‘sex at birth’, ‘biological sex’, ‘phenotypic sex’, ‘chromosomal sex’, and ‘physical difference’, as shown in Fig. 3a. The concepts within the ‘sex at birth’ cluster, explain what ‘sex at birth’ is. For example, the concept, ‘the sex of a person at birth (and recorded on the birth certificate)’, linked to the FHIR.US-CORE-BirthSex representation, helps define ‘sex at birth’. The concept for the representation OMOP.PERSON:gender_concept_id is considered to fit into the overlapping zone of both ‘sex at birth’ and ‘biological sex’ clusters as demonstrated by its concept description: ‘the biological sex of a person at birth’. According to the definition from Embryo Project Encyclopedia27, phenotypic sex, chromosomal sex, and physical difference are included in biological sex, resulting in the concepts from those clusters as subtypes of the ‘biological sex’ concept.

The clusters for the Gender topic were created to include the concepts of these four representations and their relations (see Fig. 3b). Since all the concepts explicitly mention gender (though without further explanation on what ‘gender’ means), the only differentiation comes from the purpose and the subject that is used in the concept clusters. The data element FHIR:Patient.gender is the only one explicitly referring to a patient, and the data element from OMOP’s Observation table observational_concept_id:SNOMEDCT_Gender is the most generic.

Diagnosis

Five data elements for the Diagnosis topic were identified in the 5 health data standards, with their representations and concepts, see Table 4. Based on the concept description, the major difference among them relies on the scope of the following medical terms: ‘condition’, ‘problem’, ‘medical event’, ‘diagnosis’, and ‘disease’. For example, the concept for the FHIR.Condition.code representation is ‘identification of the condition, problem or diagnosis’ versus the concept in openEHR, ‘identification of the problem or diagnosis’. There are similar differences among the data elements for the topics: Onset of Diagnosis and Severity of Diagnosis. For example, ‘start date/time of the condition, as decided by the clinician’ in HL7 FHIR versus ‘start date/time of the medical history event’ in CDISC.

There is another semantic discrepancy that potentially leads to misinterpretation, which is how to determine the onset of diagnosed diseases. In HL7 FHIR, the start of the condition is decided by a clinician; in openEHR, the start of the symptoms is decided through the first observation; in CDISC, it is not explicitly stated how the start of the medical history event is determined. It might be the case that the first observation in openEHR is reported by a patient, and that the decision made on the onset in HL7 FHIR is based on medical examination, so both data elements cannot be regarded as ‘equivalent’ to each other according to the definition of the concepts they represent.

Medication

Five data elements were identified for the Medication topic with their representations and concepts. For example, the data element Phenopackets.Treatment.agent is the only one identified in Phenopackets to represent medication data and the concept extracted was ‘The drug or therapeutic agent’; the data element openEHR.EHR-EVALUATION.Medication_summary is the only one identified in openEHR and the concept extracted was ‘summary or persistent information about the use of a single medication or group of medications’. More data elements are shown in the Supplementary Table 4 with diverse concepts. The only semantic difference lies in the scope of ‘drug’ and ‘medication’. ‘Medication’ usually refers to the drugs used for medical treatment, thus narrower than ‘drug’ which can also include vaccines and over-the-counter remedies28.

Vital sign

OMOP, HL7 FHIR, CDISC, and Phenopackets each contain one data element concerning the vital status, see more detail in the Supplementary Table 5. The concept for the representations in both Phenopacket and CDISC describes the status as living, deceased, or unknown; the concept in OMOP and HL7 FHIR reflects whether being deceased or not, thereby narrower.

Blood pressure

A total of 16 data elements were identified for the Blood Pressure topic. For example, the data element FHIR.Observation.US_Core_Blood_Pressure_Profile.component:systolic reflects the concept ‘systolic blood pressure’; the data element CDISC-SDTM.VSTESTCD:SYSBP reflects the concept ‘the maximum systemic arterial blood pressure - measured in contraction phase of the heart cycle’. See more data elements in Supplementary Table 6. The data elements in both OMOP and HL7 FHIR lack explicit descriptions, though they are bound to LOINC and SNOMED CT terms respectively. However, the bound terms only provide labels without concrete definitions, such as ‘Systolic blood pressure’ identified by LOINC:8480-6 and ‘Diastolic blood pressure (observable entity)’ identified by SNOMEDCT:271650006. As a result, the concepts for those representations are generic. On the contrary, the data elements in CDISC provide definitions together with NCIT terms so the concept reflected by their representations are more specific. Phenopackets does not have a data element specific for blood pressure, which, however, can be defined under ‘general measurement’ using an ontology term.

SSSOM Mapping

We demonstrate the use of SSSOM mappings with the data element mappings done in the Sex and Gender topics, mappings of the other topics are available on GitHub29. Twenty-one mappings in the Sex topic were created (see part of them in Table 5 and the full list in Supplementary Table 7). For example, ‘the biological sex of a person at birth’ is the concept of the data element OMOP:gender_concept_id (i.e., subject_id), which is broader than openehr:sex_assigned_at_birth, whose concept is ‘the sex of an individual determined by anatomical characteristics observed and registered at birth.’ Thereby the terms are mapped using the property skos:narrowMatch as the predicate. The mapping was manually created on ‘2024-01-29’ by the author identified as ‘ORCID:0000-0003-4715-9070’.

The hierarchy derived from these mappings is visualized in Fig. 4. In the Sex topic, FHIR:BirthSex is broader than all other six data elements; in the Gender topic, the data element OMOP:ObservationConceptGender is the broadest.

The SSSOM mappings for other topics were represented in tables and RDF, available on GitHub29. The values of data elements in the topics Sex, Gender, and Vital Status are categorical values, so SSSOM mappings among them were created. Figure 5 depicts the part of the SSSOM mappings in RDF for the data element FHIR:BirthSex, including the mappings between data elements (a), the values (b), the SIO property linking the data elements with values (c), and the mappings between values (d).

The excerpt of the SSSOM mappings in RDF for the data element FHIR:BirthSex. (a) the SSSOM mapping of FHIR:BirthSex to OMOP:gender_concept_id using the relationship ‘skos:narrowMatch’; (b) the permitted values of FHIR:BirthSex linked via the predicate from Semanticscience Integrated Ontology (SIO)25; (c) the description of the predicate; (d) the SSSOM mapping of male value in FHIR:BirthSex to the values in other health data standards: 8507 in OMOP, ‘MALE’ in Phenopacket; NCIT:C20197 in CDISC.

As illustrated in Fig. 5, FHIR:BirthSex has a broader scope compared to OMOP:gender_concept_id, as indicated by the skos:narrowMatch relation in Fig. 5a). This data element supports five possible values: F (for concept ‘female’), M (for ‘male’), OTH (for ‘other’), ASKU (for ‘ask but unknown’), and UNK (for ‘unknown’) (refer to Fig. 5b), each represented in RDF triples using the predicate sio:SIO_000217 (has quality). The unique identifier for the ‘M’ value is http://terminology.hl7.org/CodeSystem/v3-AdministrativeGender#M, which is mapped to male-related values in other data standards. For example, the ‘M’ value from FHIR is mapped as being equivalent to ‘8507’ https://athena.ohdsi.org/search-terms/terms/8507 in OMOP and ‘MALE’ in Phenopacket (see skos:exactMatch in Fig. 5d) because their concepts correspond to ‘Male’. But this ‘M’ FHIR value is broader than ‘C20197’ (male) in CDISC as the concept of ‘C20197’ is more specific and is related to biological features.

Use case

Get patients with specific data elements

The first use case is to retrieve any ‘sex’ attribute for all patients, which is operationalized by selecting all data elements whose concept is a type of ‘sex’, as opposed to ‘gender’. This scenario is designed to demonstrate how using concepts can effectively distinguish between ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ in data queries. In this case, we use umls:sex from the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) concept30 as the representation (or data element) to reflect the general ‘sex’ concept, whereas FHIR:birth_sex is the representation to reflect the more specific ‘sex at birth’ concept. As shown in Table 6a, umls:sex is linked to the six data elements by skos:narrowMatch relation, resulting in six mappings. Based on these, the SPARQL query was constructed (see Table 6b) to retrieve all triples in which predicates are data elements reflecting the ‘sex’ concept (or its sub-concept). If the query is modified to ‘Get all patients who have a value for ‘sex at birth’ registered,’ we can directly use fhir:birth_sex instead. Although both queries in this case would return the same results, the underlying rationale for each is distinct.

The second use case is to get all the patients who have the ‘biological sex’ attribute, which is operationalized as getting all data elements that are exactly matching to or narrower than OMOP:gender_concept_id because its concept is at the level of ‘biological sex’, even though it is called gender (see Table 7).

Get patients with specific sex values

The use case concerning values is to get all the patients who have ‘sex’ as ‘female’ value, which is operationalized by getting all the values whose concept is equivalent to or narrower than ‘umls:female’. As shown in Table 8, the value mappings were created (a) and the SPARQL query was formulated (b) to retrieve seven patients with sex as female (c).

Get distribution

The use case concerning distribution is to get the summarized data for the different ‘sex’ concepts, which is translated towards calculating the count of patients per sub-concept of ‘sex’. As shown in Table 9, there are 4 female patients and 7 male patients.

Discussion

In this paper, we introduced the concept-based approach for creating reusable mappings between data elements across five health data standards and demonstrated the effectiveness of the approach in use cases by querying data through data-element concepts. More findings will be discussed in depth in the sections that follow.

Insight into concept-based mappings

Concept-based mappings are represented as SSSOM mappings, which effectively capture the key information needed to harmonize data elements across health data standards. These mappings include the data elements represented by URIs (sssom:subject_id and sssom:object_id), semantics of these elements (sssom:subject_label and sssom:object_label), the harmonization of concepts through concept clusters (sssom:curation_rule), mapping relationships at the representational level (sssom:predicate_id), and other relevant metadata such as author and creation date.

-

Users can understand the rationale behind the mappings, such as one concept is broader, narrower, or exactly matches another. This insight helps users decide whether to reuse these mappings with confidence.

-

Users can query data from diverse sources when SSSOM mappings are integrated in the query pipeline, determining which data should be included or excluded based on these mapped relationships among data elements.

Additionally, the sssom:curation_rule property in SSSOM mappings has potential to enhance the reusability of mappings by referencing a specific rule (in URIs) that provides the rationale or contextual information for the mapping. For example, a curation rule such as a reference to “mapping valid only in clinical studies where sex and gender are used interchangeably” could be applied to the mapping between OMOP:gender_concept_id and fhir:administrative_gender.

In the mappings, skos:relatedMatch is used to indicate that two data elements are related in some way but not hierarchically connected. However, this relationship is more suited for theoretical discussions rather than practical data queries. We recommend that, after expert review, such relationships be replaced with more precise ones, like skos:narrowMatch, to improve the accuracy of mappings.

In practice, this approach can be used to determine if the data values represented in different data models can be mapped. Exploring the semantics behind the data elements before looking into the values will give a clearer picture on the similarity between the values. For example, consider the different definitions of categorical value ‘high blood pressure’, where American Heart Association uses a cut-off of 130 mm Hg, while WHO uses 140 mm Hg. If datasets using these different definitions were integrated, query results for ‘high blood pressure’ would not be completely reliable. The semantics behind the data values would be essential to understand this incompatibility. Although the focus of this study is not on the concept-based mappings of data values, further research in this area is needed, and the approach introduced in this manuscript can be extended to support such efforts. Once value mappings are established and represented as a set of mapping rules, the following step would involve carrying out the Extract, Transform, and Load (ETL) process.

Insight into representations and concepts

In the phase of making an inventory of data elements for the topics, we found that often multiple representations exist within the same community.

-

In CDISC, two representations CDISC CDASH SEX and CDISC SDTM SEX are bound to the same term: NCIT: C66731, but they have different semantics: ‘sex of the subject as determined by the investigator’ for CDASH versus ‘sex of the subject’ for STDM. The former should be narrower than the latter, but CDISC regards them as equivalent. It implies that even existing mappings cannot be fully trusted to represent the intended semantics.

-

In OMOP, selecting different terms can lead to multiple representations and concepts. For example, we chose SNOMEDCT:263495000 (Gender (observable entity)), so the OMOP representation, observation_concept_id:SNOMED_Gender, was utilized for analysis in this study (see Table 3). Had we chosen SNOMEDCT:33821000087103 (Gender identity (observable entity)), the representation would have differed, and the concept for it would be: “gender identity is an individual’s personal sense of being a male gender (man, boy), female gender (woman, girl), another gender(s), or no gender, that is not necessarily visible to others and must be declared by the person”. Unlike CDISC, which uses NCIT to harmonize various representations, each choice of terminology items in OMOP (and also Phenopackets) impacts both the representations and underlying concepts.

Different health data standards have a preference for different terminology systems: CDISC for NCIT; OMOP CDM for SNOMED CT; FHIR for LOINC. In OMOP, as described above, the representation and its concept are dependent on the terminology item selected from its own terminology library, particularly those in the topics Gender using observation_concept_id and Blood Pressure using measurement_concept_id. In CDISC, the NCIT terms usually provide more detail than data element description. On the contrary, LOINC terms are often less specific than the description provided in HL7 FHIR, for example, LOINC:21112-8 (https://loinc.org/21112-8/) only provides label ‘Birth date’ and FHIR HL7 provides definition ‘the date of birth for the individual’(https://build.fhir.org/patient-definitions.html#Patient.birthDate).The Phenopackets model, similar to OMOP, allows for choosing terminology items from various ontologies, for example, using CMO:0000003 within a Phenopacket block to represent ‘Blood Pressure Measurement’ data element.

For every data element, we collected semantics-reflecting content and formulated the concept. The content is objective because they are directly gathered from the source without any revision, while the concept is subjective because it is the curated version of the content for better readability and analysis. Therefore, the semantics-reflecting content is closest to the real concept that a data element is designed to capture, though it is often the mixture of diverse information.

Both concept clusters and SSSOM mappings indicate the relations between the data elements, but they function at different levels. The concept clusters focus on the concept relations at the conceptual level. These relations usually indicate whether or not one concept is included by or (partially) overlapping with another concept by analyzing their semantics, and should be based on existing evidence such as journal publications, textbooks, or even common knowledge. On the contrary, the SSSOM mappings focus on the relations between data element, i.e., at the representational level, and are based on the concept relations.

Strengths and limitations

We identify several strengths and weaknesses of our approach while developing it. First of all, a major strength is that our concept-based approach builds on the importance of conceptualization in the context of data-element mappings. This is the first study we know of to apply and demonstrate the distinction between concept and representation to the mappings of data elements. Another strength is that we utilized the existing framework SSSOM to represent mappings of data elements, enhancing both the interoperability and reusability of these mappings. This ensures that the mappings are not only standardized but also allows for representing the mapping rationale, including the underlying concepts, to be encapsulated in a URI and referenced within the ‘sssom:curation_rule’ slot. Finally, an important strength is that our mapping approach leaves the original data untouched, and there is no need to perform any data conversion when a dataset changes, as the mapping is performed dynamically.

There are some limitations. First, the mappings between data elements, presented in this paper, are indicative, and not yet reviewed by a wider community, which is required to use such mappings in practice. So while they may not be considered definitive mappings, they are successful in demonstrating the feasibility of the concept-based approach. Second, the RDF representation in the proof-of-concept is simplified using punning, so the class FHIR:BirthSex, for example, used as the property in the triple and non-resolvable, which is not recommended for real-world use cases in terms of linked data quality31. Both FHIR12 and CDISC13 provide guidelines for the creation of RDF datasets, but their structures are complex and currently cannot add more value to the demonstration.

Relation to other work

Bönisch et al.7 defined a list of so called, ‘Metadata Items’ as reference points for mapping metadata elements across health data standards. For example, the ‘versionID’ in openEHR, which tracks versions of health records and data changes, corresponds to the ‘MetadataVersion’ item. Similarly, the ‘metadata concept id’ in OMOP CDM maps to the same ‘Metadata Item’, ‘MetadataVersion’, thereby aligning the openEHR and OMOP metadata elements. While the role of ‘Metadata Item’ in their work plays a role similar to the concept proposed in our approach, they did not explicitly define the semantics or account for varying levels of granularity of concepts.

Xiao et al.8 developed the FHIROntopOMOP system, leveraging existing mappings between OMOP CDM and FHIR12. When available, mappings are usually presented in the form of a static mapping table without proper justification for the mapping. Further, efforts by Pacaci et al.9 and Boussadi et al.10 advanced data transformation and standard integration but lacked detailed mapping rationale. Manuel et al.32 developed an open-source software toolkit to convert data from common data models including CDISC and OMOP into Phenopackets, involving the step to map variables between data schemas. However, it does not describe the rationale behind the mappings.

The distinction between concept and representation is particularly important in understanding the data elements in the Sex and Gender topics because sex and gender are often used interchangeably but are clinically different. The typical example is the representation OMOP:gender_concept_id whose concept is ‘biological sex’. Dinah et al.33 did the meta-analysis on all sex and gender fields in the Mass General Brigham health system between 2018 and 2022, and found that the sex and gender demographic fields raise concern about data accuracy and exhibit considerable variability and inconsistency in how providers use them. Our approach that highlights the conceptualization of data elements and semantic harmonization can provide support in this regard.

UMLS30 is also built on the idea of concepts, similar to our approach but at different scope. UMLS defines a set of concepts to connect and standardize many health and biomedical vocabularies. For example, the UMLS concept ‘C0015674’ stands for ‘Chronic Fatigue Syndrome’. The concept links to nine definitions from diverse sources such as MESH and SNOMED CT so these nine definitions could be regarded as the representations for the concept C0015674. Mondo Disease Ontology (Mondo)34 is another resource relying on the idea of concepts but it focuses on disease names. For example, ‘MONDO:0019100’ stands for the Mondo concept ‘Neuromyelitis Optica’, and it links to terms from other sources such as DOID:8869 in Human Disease Ontology and NCIT:C84934 in NCI Thesaurus. Both UMLS and Mondo utilize concepts for harmonizing ontological terms and we can learn from them to refine our concept-based approach for harmonizing data elements across health data standards.

LinkML35 also has a built-in system for building and mapping data model elements and values, which is relevant to our approach. However, this system is often not fully utilized. For instance, the ‘slot_uri’ attribute in LinkML, which can be used to represent the semantics of data elements, is optional while it could be required for clearer, more explicit mappings. Furthermore, when multiple data models use different terminologies, replicating mappings within each individual LinkML model becomes inefficient. Our approach has the advantage of adding a separate mapping layer on top of existing models, whether or not they include explicit annotations. By extracting concepts, clustering them, and creating mappings at the representational level, our approach establishes a centralized and reusable mapping system. This not only avoids duplication but also provides a structured approach for aligning data elements across diverse models, enhancing interoperability and semantic clarity.

Impact and future work

Numerous research efforts have been dedicated to developing mapping pipelines, often without providing a clear explanation of the rationale behind the mapping decisions. Our approach addresses this gap by extracting the underlying concepts from data elements, aligning these concepts at a conceptual level to serve as the rationale, and subsequently creating mappings at the representational level.

While this approach may not solve every data model mapping problem, it provides a structured way to build reusable mappings that are both meaningful and transparent. By focusing on the semantics of data elements, it can handle a wide range of mapping scenarios, particularly where conceptual alignment is key.

In addition, extensive assessment of value mappings should be performed to enable data value integration once data element harmonization is achieved, as demonstrated in our use cases. Data values can vary significantly, and the mapping rules between them can be diverse. For example, mapping birth year to birth date or full name to first and last names requires careful consideration of these differences. Other examples include mapping height in feet versus meters, categorizing smoking status as ‘current,’ ‘former,’ or ‘never’ in one dataset versus a numerical count of cigarettes smoked per day in another, or aligning marital status across schemas where one uses ‘single,’ ‘married,’ and ‘divorced’ while another allows for more granular descriptions such as ‘legally separated’ or ‘widowed’.

In the future, we intend to apply this concept-based approach to a specific domain, such as the rare disease field. The extracted concepts and resulting mappings will undergo review by domain experts, which will not only validate the accuracy of the mappings but also test the scalability and adaptability of our approach in real-world scenarios.

Another future direction for this work could be the development of a centralized mapping system built on concepts and their representations (of existing health data standards), which would facilitate data harmonization across different contexts. For example, exploring how the broad concept of ‘allergy,’ encompassing any adverse reaction, relates to the narrower concept of ‘penicillin allergy,’ specifically focusing on allergic reactions to penicillin, could provide valuable insights. In this scenario, the broader concept of ‘allergy’ could map to a general data element for any allergic reaction in one data model, while ‘penicillin allergy’ might map to a more specific element within another data model. This would allow for flexible integration depending on the context-whether general allergy data is needed or more focused data on penicillin reactions is required. Such a concept-based approach could help guide decisions on which data to select and integrate, tailored to the specific requirements of each use case. While this direction presents potential benefits, particularly in adapting mappings to different contexts, it would require further exploration to assess its feasibility and impact. Developing a system that supports these varying levels of concept granularity could be a valuable contribution to the future of data integration across multiple domains.

Conclusion

We introduced an approach that utilizes the conceptualization of data elements for facilitating the creation of reusable mappings across health data standards. The approach leverages semantic-web representation, specifically SSSOM. The use cases, as a proof-of-concept, demonstrate that concepts are useful for data harmonization and support data query at multiple granularities. The analysis on the diversity of concepts and representations across health data standards, and the emphasis on distinguishing concepts and representations of data elements, serve as valuable input for the creation of guidelines on creating reusable mappings in the healthcare field.

Data availability

Data utilized in this article are synthetic and shared on GitHub along with code. Metadata such as mappings are included in the article or uploaded as online supplementary information.

Code availability

Implementation code is deposited on GitHub at https://github.com/sxzhang1201/concept-based-mapping. Code is shared under a permissive MIT licence.

References

Gopal, G., Suter-Crazzolara, C., Toldo, L. & Eberhardt, W. Digital transformation in healthcare–architectures of present and future information technologies. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM) 57, 328–335 (2019).

Zeadally, S. & Bello, O. Harnessing the power of internet of things based connectivity to improve healthcare. Internet of Things 14, 100074 (2021).

Nguyen, D. C. et al. Federated learning for smart healthcare: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 55, 1–37 (2022).

Sheller, M. J. et al. Federated learning in medicine: facilitating multi-institutional collaborations without sharing patient data. Scientific reports 10, 12598 (2020).

Bak, M. et al. Federated learning is not a cure-all for data ethics. Nature Machine Intelligence 1–3 (2024).

Torab-Miandoab, A., Samad-Soltani, T., Jodati, A. & Rezaei-Hachesu, P. Interoperability of heterogeneous health information systems: a systematic literature review. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 23, 18 (2023).

Bönisch, C., Kesztyüs, D. & Kesztyüs, T. Harvesting metadata in clinical care: a crosswalk between fhir, omop, cdisc and openehr metadata. Scientific Data 9, 659 (2022).

Xiao, G. et al. Fhir-ontop-omop: Building clinical knowledge graphs in fhir rdf with the omop common data model. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 134, 104201, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2022.104201 (2022).

Pacaci, A., Gonul, S., Sinaci, A. A., Yuksel, M. & Laleci Erturkmen, G. B. A semantic transformation methodology for the secondary use of observational healthcare data in postmarketing safety studies. Frontiers in pharmacology 9, 435 (2018).

Martínez-Costa, C. & Schulz, S. Validating ehr clinical models using ontology patterns. Journal of biomedical informatics 76, 124–137 (2017).

Miles, A. & Bechhofer, S. Skos simple knowledge organization system reference. W3C recommendation (2009).

HL7. Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR). https://hl7.org/fhir/ 19 January 2024.

Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC). Study Data Tabulation Model (SDTM)https://www.cdisc.org/ 19 January 2024.

Udry, J. R. The nature of gender. Demography 31, 561–573 (1994).

Haig, D. The inexorable rise of gender and the decline of sex: Social change in academic titles, 1945–2001. Archives of sexual behavior 33, 87–96 (2004).

Bhargava, A. et al. Considering sex as a biological variable in basic and clinical studies: an endocrine society scientific statement. Endocrine reviews 42, 219–258 (2021).

ISO/IEC 11179-6:2023, Information technology – Metadata registries (MDR) https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso-iec:11179:-3:ed-4:v1:en (2023).

Matentzoglu, N. et al. A simple standard for sharing ontological mappings (sssom). Database 2022 (2022).

World Wide Web Consortium and others. RDF 1.1 concepts and abstract syntax (2014).

OHDSI. Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) common data model (CDM). https://github.com/OHDSI/CommonDataModel Accessed: 19 January 2024.

openEHR Foundation. openEHR. https://www.openehr.org/ 19 January 2024.

Jacobsen, J. O. et al. The ga4gh phenopacket schema defines a computable representation of clinical data. Nature biotechnology 40, 817–820 (2022).

W3C. OWL2 New Features - F12:Punning, https://www.w3.org/TR/owl2-new-features/#F12:_Punning 31 March 2022.

Zhang, S. Proof of Concept for Concept-based Mappings, https://github.com/sxzhang1201/concept-based-mapping 27 January 2024.

Dumontier, M. et al. The semanticscience integrated ontology (sio) for biomedical research and knowledge discovery. Journal of biomedical semantics 5, 1–11 (2014).

Richards, C. et al. Non-binary or genderqueer genders. International Review of Psychiatry 28, 95–102 (2016).

Schnebly, R. A. Biological sex and gender in the united states. Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2022).

FDA. FDA Glossary of Terms, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/drugsfda-glossary-terms 19 January 2024.

Zhang, S. The SSSOM Mappings, https://github.com/sxzhang1201/concept-based-mapping/tree/main/sssom-mappings 27 January 2024.

Bodenreider, O. The unified medical language system (umls): integrating biomedical terminology. Nucleic acids research 32, D267–D270 (2004).

Zhang, S., Benis, N. & Cornet, R. Automated approach for quality assessment of rdf resources. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 23, 90 (2023).

Rueda, M., Leist, I. C. & Gut, I. G. Convert-pheno: A software toolkit for the interconversion of standard data models for phenotypic data. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 149, 104558, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2023.104558 (2024).

Foer, D. et al. Utilization of electronic health record sex and gender demographic fields: a metadata and mixed methods analysis. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association ocae016 (2024).

Vasilevsky, N. et al. Mondo disease ontology: harmonizing disease concepts across the world. In CEUR Workshop Proceedings, CEUR-WS, vol. 2807 (2020).

LinkML Project. LinkML, https://linkml.io/ 19 Septmber 2024.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the funding support from the European Joint Programme on Rare Diseases (EJP RD). We also appreciate the contribution of Philip van Damme, Rowdy de Groot, Pablo Alarcón Moreno, Núria Queralt-Rosinach to the initial discussion during the design phase of this study. This work was supported by funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the EJP RD COFUND-EJP N° 825575. The funder has had no involvement in the design of the study, nor in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed to this work. S.Z. conducted the mapping work and analyzed the results. N.B. and R.C. are supervisors providing valuable guidance in the whole research work, including but not limited to the design of the study, reviewing the mappings, and the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Cornet, R. & Benis, N. Cross-Standard Health Data Harmonization using Semantics of Data Elements. Sci Data 11, 1407 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04168-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04168-1