Abstract

Cryptosporidium spp. are medically and scientifically relevant protozoan parasites that cause severe diarrheal illness in infants, immunosuppressed populations and many animals. Although most human Cryptosporidium infections are caused by C. parvum and C. hominis, there are several other human-infecting species including C. meleagridis, which are commonly observed in developing countries. Here, we annotated a hybrid long-read Oxford Nanopore Technologies and short-read Illumina genome assembly for C. meleagridis (CmTU1867) with DNA generated using multiple displacement amplification. The assembly was then compared to the previous C. meleagridis (CmUKMEL1) assembly and annotation and a recent telomere-to-telomere C. parvum genome assembly. The chromosome-level assembly is 9.2 Mb with a contig N50 of 1.1 Mb. Annotation revealed 3,919 protein-encoding genes. A BUSCO analysis indicates a completeness of 96.6%. The new annotation contains 166 additional protein-encoding genes and reveals high synteny to C. parvum IOWA II (CpBGF). The new C. meleagridis genome assembly is nearly gap-free and provides a valuable new resource for the Cryptosporidium community and future studies on evolution and host-specificity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Cryptosporidium is an apicomplexan protozoan parasite of global medical, scientific, and veterinary significance that can cause moderate-to-severe diarrhea in humans and animals1. It is the leading cause of waterborne disease outbreaks in the United States2,3. Though cryptosporidiosis occurs in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals, it is especially severe in immunocompromised and elderly populations as well as in children, resulting in persistent infection, malnutrition, and, in some cases, death3,4,5. In 2019, the Global Burden of Disease study found 133,422 global deaths and an annual loss of 8.2 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) due to Cryptosporidium6. C. meleagridis is an avian and mammalian-infecting Cryptosporidium species that was first described in turkeys7,8. Human infections with Cryptosporidium are caused predominantly by C. parvum and C. hominis, but species such as C. meleagridis can also infect humans. In fact, C. meleagridis is the third most common human-infecting Cryptosporidium species following C. parvum and C. hominis9. Though generally less common, C. meleagridis infection has been reported to be as common as C. parvum in some parts of the world and can lead to death in rare cases10,11.

Currently, 17 of the >30 reported Cryptosporidium species have assembled genome sequences. Twelve species have annotated genome sequences including C. andersoni, C. bovis, C. canis, C. felis, C. hominis, C. meleagridis, C. muris, C. parvum, C. ryanae, C. tyzzeri, C. ubiquitum and C. sp. Chipmunk genotype12,13. Cryptosporidium spp. have eight chromosomes and genome sizes of ~9 Mb. The only C. meleagridis genome sequence, strain UKMEL1 (CmUKMEL1), contains gaps and is assembled into 57 contigs. Historically, it has been challenging to sequence the genome of Cryptosporidium parasites. Sustainable in vitro culture and cloning are not possible. Thus, sequencing a bulk population of parasites, when enough can be isolated, has been the preferred approach. Recently, a new method was implemented to generate genome sequences for Cryptosporidium using multiple displacement amplification, a whole genome amplification (WGA) approach. It was tested on 10 ng of genomic DNA from C. meleagridis strain TU1867 (CmTU1867) which provided sufficient DNA for library construction and generation of a high-quality genome sequence using Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) long-read sequencing14. Here we share a chromosome-level assembly and reannotation of the C. meleagridis genome.

Whole genome sequencing and assembly

The newly generated CmTU1867 genome assembly contains an additional 201,275 base pairs (bp) of sequence relative to CmUKMEL1. The largest contig in the new assembly is 632,735 bp longer than the largest contig in CmUKMEL1. We also note a larger N50 value in the new assembly (Table 1). For comparison, a recent telomere-to-telomere, T2T, genome assembly for the closely related and highly syntenic species, C. parvum IOWA II (CpBGF) is provided15. This high-quality C. meleagridis genome assembly results from a new experimental approach designed to help generate long-read genome sequences from limiting quantities of genomic DNA and is an important resource that will facilitate our understanding of Cryptosporidium evolution and host specificity.

The initial genome assembly contained 8 chromosomes and 5 contigs ranging in size from 681–30,300 bp, 2 of which were later identified as contamination and removed. Two additional contigs were manually created (“contig_10” and “contig_11”) from the beginnings of chromosome 2 and chromosome 6 due to detection of assembly artifacts in these chromosomes. The final assembly contains 8 chromosomes and contigs 9–13 (Table 1). Contig_9 and contig_13 have regions of sequence identical to parts of chromosomes 1 and 3, respectively, but assembled separately from the chromosomes. The chromosomes of C. meleagridis are numbered and oriented according to their homology with the highly syntenic C. parvum. The new assembly is highly syntenic to the previous CmUKMEL1 assembly at the nucleotide level (Fig. 1).

In comparison to CmUKMEL1, the new CmTU1867 assembly lacks telomeres, except for chromosome 5, which has one assembled telomere. A search of the ONT long-reads, revealed several reads with telomere sequences that did not assemble. Though these reads did not assemble, regions of the read that did not contain the telomere pattern matched unique sequences in the assembled chromosomes. By mapping these reads back to the genome assembly, we identified three additional telomeres that could be placed manually at the 5′ and 3′ ends of chromosome 3, and the 5′ end of chromosome 4. At least 4 telomere-containing long-reads mapped to these regions with at least 1 long (>1 kb) read that extended into unique regions of the chromosome. However, due to the low number of reads in support of these telomeres, we did not extend the ends of chromosomes in the assembly with these telomere-containing reads.

Genome annotation

The new CmTU1867 genome assembly was annotated using the previous CmUKMEL1 annotation, a recent CpBGF annotation, orthology analysis, and de novo gene prediction. Gene expression data for CmTU1867 are not available to assist with the annotation, so UTRs are not predicted. Annotation of CmTU1867 reveals 166 additional protein-encoding genes and numerous additional ribosomal RNAs (Table 2).

A comparison of the synteny of the protein-encoding genes and rRNAs between CmTU1867 and CpBGF revealed highly syntenic chromosomes (Fig. 2). The new CmTU1867 genome sequence has 16 additional ribosomal RNA genes compared to CmUKMEL1 (Table 2). The 5 small, 5.8S rRNA units are found on chromosomes 1, 2, 7, 8 (Fig. 2). The six 5S rRNAs in CmTU1867 are in 2 clusters of 3, on chromosome 3 and 7 (Fig. 2). In CpBGF the cluster of 5S rRNAs on chromosome 3 contains 2 rRNAs whereas in CpIOWA-ATCC and CmTU1867, the cluster of 5S rRNAs on chromosome 3 contains 3 rRNAs. These patterns may arise because of variation in the copy number of the 5S rRNA within a population of parasites or among different species of Cryptosporidium or compressions during genome assembly. When CmTU1867 reads were mapped to the assembly at regions where there are 5S rRNA clusters in chromosomes 3 and 7, we saw relatively even coverage throughout the region. However, CpBGF shows 2-3X read compression at this locus on chromosome 3 and 7 suggestive of population variation. One of the unassembled contigs, contig_9, has an additional 18S/28S cluster. However, due to the fact that we are not able to find a chromosomal location for it despite long-read sequencing and since our sample is not clonal, we do not have sufficient evidence to conclude its status.

Protein synteny analysis of the eight chromosome-level contigs of CmTU1867 and Cryptosporidium parvum, CpBGF. Circos plot rings, moving from the center to the exterior illustrate shared ortholog clusters between CmTU1867 and CpBGF, number of base pairs in 50,000 bp increments, GC content histogram, and gene density. Locations of rRNA genes are as indicated.

While annotating, we noticed several genes that encoded a single long protein in CmUKMEL1 but were annotated as two distinct genes in CpBGF. Upon investigation, we discovered that these gene annotations vary in size in several Cryptosporidium species. In CmTU1867, we have kept the long protein annotation when it is observed. There are 20 cases where the single long protein in C. meleagridis does not appear to exist as a single open reading frame in CpBGF, (Table 3). A lack of RNAseq evidence for C. meleagridis makes it challenging to validate the existence of these long open reading frames whereas C. parvum has a large quantities of expression data available. We made a note in the submitted CmTU1867 annotation if the gene is annotated as two or three distinct genes in other species. Two of the 20 CmTU1867 proteins are annotated as 3 distinct proteins in CpBGF (Table 3).

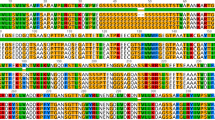

Interestingly, each of the 5 annotated 18S and 28S rRNAs has a putative protein-encoding gene within it (Table 4). Our submitted annotation does not contain any of these putative ORFs as their presence would be so unusual it cannot be accepted by the NCBI GenBank. However, we note, they may exist. The 18S rRNA genes encode a putative intron-encoded homing endonuclease. While we detect the presence of this putative protein, we do not detect an intron in the 18S rRNA. The six putative homing endonuclease protein sequences in the 18S rRNAs are not identical due to a guanine deletion at position 1061 in two of the five 18S rRNAs (Chr1 and Chr7). This results in a premature stop codon in three of the putative homing endonuclease sequences (Fig. 3). This indel is likely due to an ONT homopolymer sequencing artifact. BLASTp searches of other Cryptosporidium species revealed annotations of this gene in C. ubiquitum and C. felis. We note that annotation in other species does not make these genes real, only proteomics can confirm them, thus they are not included in our submitted annotation.

The six putative senescence associated proteins encoded in the 28S rRNAs are identical. This protein is found in BLASTp searches in C. hominis TU502, C. canis, C. ubiquitum, and C. muris. This protein has an ART2/RRT15 domain according to InterPro. As was the case with the putative intron homing endonuclease in the 18S genes above, given the location, we have not included these proteins in the submitted annotation due to a lack of evidence for their existence.

Comparison with previous assemblies

The annotation was assessed by comparing the CmTU1867, CmUKMEL1 and CpBGF protein-coding sequence gene content using orthology-based algorithms. Several putative species-specific single copy genes were identified (Table 5). We identified 23 species-specific genes in CmTU1867, 11 in CmUKMEL1, and 39 in CpBGF (Table 5). This finding makes sense because CpBGF, which is a T2T assembly, is the most complete of the three assemblies and CmTU1867 is a more complete genome assembly than CmUKMEL1. To assess whether species-specific genes were located in sub-telomeric regions, the first and last 25 genes of each chromosome were assessed for the presence of species-specific genes. We observe that the putative species-specific genes are not enriched in sub-telomeric regions (bolded gene names in Table 5), rather, they are scattered throughout the genome. If real, the evolutionary origin of these genes is intriguing. However, these results are derived from as of yet, incomplete genome assemblies for C. meleagridis and require further validation.

All orthogroups (multiple shared derived genes – orthologs or paralogs) as opposed to the single-copy genes in Table 5, that were not shared by all three genome assemblies were investigated. Some of the orthogroups fall at the ends of chromosomes in C. parvum that extended beyond the ends of the CmTU1867 and CmUKMEL1 chromosomes. Other times they were unannotated in one species or the other but present in the syntenic genome sequence region(s). When we found unannotated proteins that were not initially detected in CmTU1867, we manually added these genes to the submitted annotation. Ultimately, we found very few orthogroups that were unique to a subset of species (Fig. 4). The manual validation of the orthogroups is presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Venn diagram of orthogroup search results following manual validation. Orthogroup comparison among the new CmTU1867, the previous CmUKMEL1, and the newly released reference genome, CpBGF. See Fig. 6 for the pre-validation results. Arrows link the list of gene IDs found in the smaller orthogroups that are unique to a species or shared by two species.

Methods

Whole genome sequencing and assembly

C. meleagridis isolate TU1867 genomic DNA was obtained from BEI Resources (cat. number NR-2521 ATCC, Manassas, VA). A total of 10 ng of C. meleagridis DNA was amplified through whole genome amplification using multiple displacement amplification (MDA), followed by T7 endonuclease debranching yielding 400 ng debranched DNA14. Following sequence generation and assembly, polishing and annotation proceeded as in (Fig. 5). The sequence was polished with existing reads from the NCBI GenBank Sequence read archive accession SRR79356116.

Experimental workflow for genome sequencing, assembly, annotation, and validation. Bioinformatics workflow for assembly and annotation of the DNA derived from CmTU1867 WGA. Green boxes represent initial steps as well as new data used for parts of the pipeline and blue boxes represent subsequent downstream analyses of the data generated. The illustration was generated in BioRender.

ONT library preparation used the SQK-RBK004 Rapid Barcoding Sequencing Kit (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed on an ONT MinION device with R9.4.1 flow cells and bases were called by guppy v.6.4.2 using the high-accuracy base call model. The long-read fastq reads were assembled using Flye v.2.8.217 with the–nano-raw option and -g 9 m. The draft long-read genome assembly was polished with PolyPolish v.0.5.018 using default parameters to increase the accuracy of the base calls by using C. meleagridis strain TU1867 Illumina sequences (NCBI accession SRX253214) generated elsewhere. Intermediate files needed for PolyPolish were generated using BWA v.0.7.1719. The resulting contigs were ordered and oriented to match the CpIOWA-BGF T2T genome assembly15 (GCA_035232765.1), called CpBGF in this manuscript, using AGAT20 v. 1.1.0 PERL script agat_sq_reverse_complement.pl, GenomeTools21, and the progressive Mauve alignment v 1.1.322 in Geneious Prime v 2023.2.123. Contamination was detected by searching the NCBI nr database using BLAST24 (BLASTx default parameters) and FCS-GX25 (Fig. 5). Contaminant contigs were removed from further analysis. Telomeres were identified, as in CpBGF15 using the telomere-locating python script FindTelomeres to find the Cryptosporidium telomere repeat 5’-CCTAAA-3’ and its complement at the ends of assembled contigs (https://github.com/JanaSperschneider/FindTelomeres). The unassembled ONT long-reads were also searched for this telomere repeat with FindTelomeres and reads with telomeres were mapped back to the genome assembly. Read-mapping to the whole genome assembly was performed using minimap2 v.2.26 with the option –secondary = no to prevent multi-mapping. Genome statistics were generated using the GenomeTools v.1.6.221 programs gt stat and gt seqstat. AGAT v.1.1.020 PERL scripts agat_sq_stat_basic.pl and agat_sp_statistics.pl were used to generate statistical information with default parameters.

Genome annotation

Tracks for manual annotation were generated using a local Apollo2 server26 using two approaches: (1) an orthology based annotation transfer using the tool Liftoff27 and (2) an ab initio gene prediction using Augustus28 trained with C. parvum IOWA-ATCC12 (GCA_015245375.1) and CmUKMEL1 (GCA_001593445.1) protein sequences from CryptoDBv.5029. Annotation Liftoff tracks were created from the current CmUKMEL1, CpBGF, and CpIOWA-ATCC annotated genes with the -copies flag to look for extra gene copies. In situations where AUGUSTUS and Liftoff gene structures disagreed, the conflicting gene models were searched using BLASTp in CryptoDB to check for the gene structure that was most abundant in existing annotations. As there are no available RNA-seq data for C. meleagridis there is no evidence to confirm gene predictions and annotate UTRs. Tracks for prediction and manual annotation of rRNAs were created using barrnap30 with the parameters–kingdom euk–outseq Cmel_barrnap.fasta–evalue 1e-06–lencutoff 0.8 Cmel_genome.fasta. TRNAscan 2.031 was used to predict tRNAs using default parameters. Functional annotation was generated with Blast2GO32 (using BLASTp, the nr database, word size 5, and e-value 1e-5) and compared with results from the reference T2T CpBGF genome functional annotation. Edits to the CmTU1867 gff file gene names were performed with basic bash and awk commands. InterPro33 was used for classification of protein families investigated in Table 3 and for the genes encoded within rRNAs.

Comparative genomics

A comparison of orthologous genes between the new C. meleagridis assembly and the previous C. meleagridis assembly34 was completed using Orthofinder v2.5.5 which was run in a conda environment using the latest Anaconda release35 (2024.02-1) with default parameters (latest Diamond algorithm36) and visualized using OrthoVenn337. Figure 4 represents the orthology results following extensive manual validation (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 1) of each orthogroup difference. Manual analyses utilized BLASTp searches of both NCBI and CryptoDB29. Orthology, genome, and rRNA comparisons were created using Circos38. The configuration file for Circos was created following the Circos documentation and run using the command: circos -conf config_file.conf. Additionally, TBTools39 was used to visualize the circos plot. In TBTools, the “Advanced Circos” feature was selected. The ChrLen File and the Links File were generated manually following the Circos format. The rRNA features were added to the plot in the “Set Input Genome Feature List” option on TBTools. Gene density and GC content were created in TBTools following the TBTools documentation with default parameters. The genome comparisons between CmUKMEL1 and CmTU1867 were created using JupiterPlot40. The JupiterPlot was made using the command: jupiter name = $prefix ref = $reference fa = $scaffolds where the ref variable is set to the reference genome in FASTA format and the fa variable is set to the set of scaffolds in FASTA format. The general parameters were set to the default (t = 4) and karyotype options were slightly modified (m = 10000, ng=0, i=0, g = 1, gScaff=100000, labels = ref). Link options followed the default options (maxGap = 100000, minBundleSize = 50000, MAPQ = 50, linkAlpha=5). CmTU1867 long reads were mapped back to contig regions containing 5S rRNA clusters using minimap2 with --secondary = no to account for multi-mapping. The raw orthogroups were analyzed and validated extensively to create the final Venn diagram (Fig. 4). Any protein that was syntenic to proteins in the other two genome sequences was moved into an orthogroup with those proteins. Proteins that were found in the sequence of the other two genome sequences but were not annotated in one or more genome(s) were also moved into an orthogroup and added to the Venn diagram.

Data Records

The genomic sequence, reads SRR2728254241, and metadata for the Cryptosporidium meleagridis TU1867 strain have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information, NCBI GenBank under BioProject accession number PRJNA102204742. This whole genome shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession JBCHVM00000000043. The version described in this paper contains WGS scaffolds JBCHVM010000001-JBCHVM0100000013.

Technical Validation

CmTU1867 assembly completeness was evaluated using the Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) software v.5.5.044 to search against apicomplexan databases (apicomplexa_odb10) which contain 446 orthologous single-copy genes in total. The results showed an overall completeness score of 96.6% (n = 446). Of these, 430 (96.4%) single-copy genes were retrieved of which 1 (0.224%) was duplicated. These results indicate high completeness of the genome assembly.

Further analysis of the assembly and annotated protein encoding regions utilized an orthology comparison of CmTU1867, CmUKMEL1, and CpBGF with the OrthoFinder algorithm and the results were visualized in OrthoVenn3 as described in the methods (Fig. 5). Orthogroups belonging to CmTU1867 only, CpBGF only, CmUKMEL and CpBGF only, and CmUKMEL1 and CmTU1867 only were extensively analyzed (Supplementary Table 1). Several genes found only in CpBGF were shown to be subtelomeric in both CmUKMEL1 and CmTU1867 and thus likely missing from the incomplete chromosome ends of CmTU1867. Several genes encoding short <100 amino acid proteins found in both CmTU1867 and CmUKMEL1 exist in CpBGF but are unannotated. Following these analyses, a new Venn diagram (Fig. 4) was created that represents the revised, validated findings.

We additionally found one putative open-reading frame (ORF) predicted by AUGUSTUS in CmTU1867 Chr4 region 828518–828700 bp that was not in CmUKMEL1, CpBGF, or any other species according to BLASTp and BLASTn searches. We removed this putative gene from our annotation since we could not validate it with RNAseq data or orthology, but it may be a gene unique to C. meleagridis detected by the improved assembly.

Code availability

Pipelines and code involved in processing the data were executed by following the respective manuals of the bioinformatics software programs used. A custom script was generated to convert OrthoFinder output into the ClusterVenn input format on OrthoVenn3.

Genome pre-assembly parameters:

1. Guppy

guppy_basecaller –i./fast5_pass –s./guppy_out –c dna_r9.4.1_450bps_hac.cfg --num_callers 2 --cpu_threads_per_caller 1

Assembly and gene calling parameters:

1. Flye

flye --nano-raw ../Cmel.fastq -o Cmel_flye -g 9 m

2. PolyPolish

bwa index polished_1.fasta

bwa mem -t 16 -a polished_1.fasta SRR793561_1.fastq.gz > alignments_1.sam

bwa mem -t 16 -a polished_1.fasta SRR793561_2.fastq.gz > alignments_2.sam

polypolish_insert_filter.py --in1 alignments_1.sam --in2 alignments_2.sam --out1 filtered_1.sam --out2 filtered_2.sam

polypolish polished_1.fasta filtered_1.sam filtered_2.sam > polished_2.fasta

3. AGAT: agat_sq_reverse_complement.pl (for reorienting annotations)

agat_sq_reverse_complement.pl --gff Cmel_annotations_Chr4_Chr6.gff3 --fasta Cmel_genome.fasta -o Cmel_annotations_reoriented.gff3

4. GenomeTools (for validating after reorienting chromosomes)

gt gff3validator Cmel_annotations_reoriented.gff3

5. BLASTx

blastx -query Cmel_genome.fasta -db nr -out results_blastx.txt -outfmt 6 -evalue 1e-5 -num_threads 4

6. FCS-GX

python $EBROOTNCBIMINFCS/fcs.py screen genome --fasta Cmel_genome.fasta --out-dir./fcs_gx_out/ --gx-db “$GXDB_LOC/gxdb” --tax-id 93969

7. FindTelomeres.py (on the reads)

https://github.com/JanaSperschneider/FindTelomeres

python FindTelomeres_Crypto_Repeat.py Cmel_pool.fasta

8. Minimap2

minimap2 -a --secondary = no Cmel_genome.fasta reads_with_telomeres.fastq > telomere_map.sam

9. GenomeTools (for statistics)

gt stat Cmel.gff3

10. AGAT: agat_sq_stat_basic.pl and agat_sp_statistics.pl (for statistics)

agat_sq_stat_basic.pl -i Cmel.gff3

agat_sp_statistics.pl -gff Cmel.gff3

11. AUGUSTUS

perl ~/Augustus/scripts/autoAugTrain.pl --cpus=10 --trainingset=CryptoDB-64_CparvumIOWA-ATCC_AnnotatedProteins.fasta --species=trained_species -g=genome.fa --workingdir=./autoAug --optrounds = 1

augustus --gff3=on --stopCodonExcludedFromCDS=false --species=trained_species–softmasking=0–AUGUSTUS_CONFIG_PATH=./augustus/config --strand=both–genemodel=partial Cmel_genome.fasta>augustus.gff

12. Liftoff

liftoff -g CpBGF.gff3 -o bgf -infer_genes -infer_transcripts -polish Cmel_genome.fasta bgf.fa

13. Blastp in CryptoDB (default)

https://cryptodb.org/cryptodb/app/workspace/blast/new

Expectation value: 10; Max Target Sequences: 100; Max matches in query range: 0; Word Size: 6; Scoring Matrix: BLOSUM62; Gap Costs (Open/Extension): 11,1; Compositional adjustments: Conditional compositional score matrix adjustment Low complexity regions: no filter; Mask for lookup table: false; Mask lower case letters: false

14. Barrnap

barrnap --kingdom euk –outseq Cmel_barrnap.fasta --evalue 1e-06 --lencutoff 0.8 Cmel_genome.fasta

15. TRNAscan

tRNAscan-SE Cmel_genome.fasta

16. Blast2GO

Installed Blast2GO locally

Parameters: BLASTp, the nr database, word size 5, and e-value 1e-5

17. InterPro (online website used – default)

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/

All Member databases selected

Comparative genomics parameters:

1. OrthoFinder in Anaconda (raw figure in technical validation):

source activate /orthology_analysis/env-ortho

conda install -c bioconda diamond

conda install orthofinder

orthofinder -f FASTAS

2. Blastp NCBI (default):

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PAGE=Proteins

Database: nr; Max target sequences = 100; Short queries (checked); Expect threshold: 0.05; Word size = 5; Max matches in a query range: 0; Matrix BLOSUM62; Gap Costs: Existence: 11 Extension: 1; Compositional adjustments: Conditional compositional score matrix adjustment

3. Blastp CryptoDB (default):

https://cryptodb.org/cryptodb/app/workspace/blast/new

Expectation value: 10; Max Target Sequences: 100; Max matches in query range: 0; Word Size: 6; Scoring Matrix: BLOSUM62; Gap Costs (Open/Extension): 11,1; Compositional adjustments: Conditional compositional score matrix adjustment Low complexity regions: no filter; Mask for lookup table: false; Mask lower case letters: false

4. Circos:

circos -conf config_file.conf

5. ChrLen file for Circos (CmTU1867 contigs indicated by “1–8” and CpBGF contigs indicated by “9–16”):

1880501

2980476

31087121

41105563

51085659

61311173

71306104

81365597

9919856

10992060

111102418

121107426

131085856

141308482

151363666

161379419

6. TBTools:

“Advanced Circos” selected; ChrLen File created manually, Links File generated manually; rRNA features added in “Set Input Genome Feature List” option; Gene density: “Sequence Toolkits” - > “GFF3/GTF Manipulate” - > “Gene Density Profile”, Input File: Cmel.gff3, Output File: CmelGeneDensity.profile (repeat for CpBGF); GC content: “Sequence Toolkits” - > “Fasta Tools” - > “Fasta Window Stat”, Input Genome Sequence File: Cmel_genome.fasta, Output file Prefix: Cmel_genome.genome.Window.Stat

7. Jupiterplot:

jupiter name = $prefix ref = $reference fa = $scaffolds

Technical validation parameters:

1. BUSCO:

busco -i < genome.fasta > -l./apicomplexa_odb10 -o BUSCO_CM.txt -m genome

2. OrthoFinder in Anaconda (see above)

Formatting OrthoFinder Result for OrthoVenn3’s ClusterVenn:

awk -F’: ‘ ‘{for (i = 2; i<= NF; i++) if ($i!~ /^OG/) printf “%s%s”, sep, $i; sep=“\n”}’

Orthogroups.txt | tr -d ‘:’ |

awk ‘{

for (i = 1; i < = NF; i + + ) {

if ($i ~ /^CmeUKMEL1/)

$i = “CryptoDB-55_CmeleagridisUKMEL1_AnnotatedProteins|” $i;

else if ($i ~ /^cmbei/)

$i = “CmBEI_proteins_file|” $i;

else if ($i ~ /^cpbgf/)

$i = “CpBGF_protein_file|” $i;

}

}’ |

awk ‘{

for (i = 1; i < = NF; i + + ) {

if ($i ~ /^CmBEI/) {

cmbei = cmbei $i “ ”

} else if ($i ~ /^CpBGF/) {

cpbgf = cpbgf $i “ ”

} else if ($i ~ /^Crypto/) {

crypto = crypto $i “ ”

}

}

print cmbei cpbgf crypto

cmbei = “”

cpbgf = “”

crypto = “”

}’ > Orthogroups2.txt

Configuration File:

#Add this to run circos faster

#alias circos = …

#Append this line to the ~/.bashrc to load when starting a new session

# Chromosome name, size, and color definition

karyotype = ChromosomeContigLabels.txt

<ideogram> <spacing> default = 0.005r < /spacing > radius = 0.50r

thickness = 20p

fill = yes

stroke_color = dgrey

stroke_thickness = 2p

show_label = yes

#see etc/fonts.conf for list of font names

label_font = default

label_radius = 1r + 75p

label_size = 60

label_parallel = no < /ideogram > show_ticks = yes

show_tick_labels = yes < ticks > radius = 1r + 10p

color = black

thickness = 3p

# the tick label is derived by multiplying the tick position

# by ‘multiplier’ and casting it in ‘format’:#

# sprintf(format,position*multiplier)#

multiplier = 1e-6

# %d - integer

# %f - float

# %.1 f - float with one decimal

# %.2 f - float with two decimals#

# for other formats, see http://perldoc.perl.org/functions/sprintf.html

format = %d< tick >spacing=70000 u

size = 50p< /tick ># < tick >#spacing = 25000 u

#size = 15p

#show_label = yes

#label_size = 20p

#label_offset = 10p

#format = %d

# < /tick >< /ticks >########### NEW< links >< link >file = Links.txt

#color = black_a5

radius = 0.95r

bezier_radius = 0.1r

thickness = 15

ribbon = yes< /link >< /links >##########

< image ># Included from Circos distribution.<< include etc/image.conf >>#To modify the size of the output image, default is 1500

#radius* = 3000p< /image>

<<include etc/colors_fonts_patterns.conf>>

<<include etc/housekeeping.conf>>

References

Ryan, U., Fayer, R. & Xiao, L. Cryptosporidium species in humans and animals: current understanding and research needs. Parasitology 141, 1667–1685, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182014001085 (2014).

Hlavsa, M. C. et al. Outbreaks Associated with Treated Recreational Water - United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 67, 547–551, https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6719a3 (2018).

Kotloff, K. L. et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet 382, 209–222, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60844-2 (2013).

Girma, M., Teshome, W., Petros, B. & Endeshaw, T. Cryptosporidiosis and Isosporiasis among HIV-positive individuals in south Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 14, 100, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-100 (2014).

Investigators, M.-E. N. The MAL-ED study: a multinational and multidisciplinary approach to understand the relationship between enteric pathogens, malnutrition, gut physiology, physical growth, cognitive development, and immune responses in infants and children up to 2 years of age in resource-poor environments. Clin Infect Dis 59(Suppl 4), S193–206, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu653 (2014).

Gilbert, I. H. et al. Safe and effective treatments are needed for cryptosporidiosis, a truly neglected tropical disease. BMJ Glob Health 8 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2023-012540 (2023).

Akiyoshi, D. E. et al. Characterization of Cryptosporidium meleagridis of human origin passaged through different host species. Infect Immun 71, 1828–1832, https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.71.4.1828-1832.2003 (2003).

Slavin, D. Cryptosporidium meleagridis (sp. nov.). J Comp Pathol 65, 262–266, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0368-1742(55)80025-2 (1955).

Fayer, R. Taxonomy and species delimitation in Cryptosporidium. Exp Parasitol 124, 90–97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exppara.2009.03.005 (2010).

Stensvold, C. R., Beser, J., Axen, C. & Lebbad, M. High applicability of a novel method for gp60-based subtyping of Cryptosporidium meleagridis. J Clin Microbiol 52, 2311–2319, https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00598-14 (2014).

Cama, V. A. et al. Cryptosporidium species and genotypes in HIV-positive patients in Lima, Peru. J Eukaryot Microbiol 50(Suppl), 531–533, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.2003.tb00620.x (2003).

Baptista, R. P. et al. Long-read assembly and comparative evidence-based reanalysis of Cryptosporidium genome sequences reveal expanded transporter repertoire and duplication of entire chromosome ends including subtelomeric regions. Genome Res 32, 203–213, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.275325.121 (2022).

Agyabeng-Dadzie, F., Xiao, R. & Kissinger, J. C. Cryptosporidium Genomics - Current Understanding, Advances, and Applications. Current Tropical Medicine Reports. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40475-024-00318-y (2024)

Agyabeng-Dadzie, F. et al. Evaluating the benefits and limits of multiple displacement amplification with whole-genome Oxford Nanopore Sequencing. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.09.579537 (2024).

Baptista, R. P., Xiao, R., Li, Y., Glenn, T. C. & Kissinger, J. C. New T2T assembly of Cryptosporidium parvum IOWA annotated with reference genome gene identifiers. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.13.544219 (2023).

Keely, S. P. Cryptosporidium meleagridis clinical isotate TU1867 isolated from gnotobiotic piglets. NCBI Sequence Read Archive http://identifiers.org/insdc.sra:SRR793561 (2011).

Kolmogorov, M., Yuan, J., Lin, Y. & Pevzner, P. A. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat Biotechnol 37, 540–546, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0072-8 (2019).

Wick, R. R. & Holt, K. E. Polypolish: Short-read polishing of long-read bacterial genome assemblies. PLoS Comput Biol 18, e1009802, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009802 (2022).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 (2009).

Dainat, J. AGAT: Another Gff Analysis Toolkit to handle annotations in any GTF/GFF format.

Gremme, G., Steinbiss, S. & Kurtz, S. GenomeTools: a comprehensive software library for efficient processing of structured genome annotations. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform 10, 645–656, https://doi.org/10.1109/TCBB.2013.68 (2013).

Darling, A. E., Mau, B. & Perna, N. T. progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One 5, e11147, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0011147 (2010).

Kearse, M. et al. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28, 1647–1649, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199 (2012).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215, 403–410, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 (1990).

Astashyn, A. et al. Rapid and sensitive detection of genome contamination at scale with FCS-GX. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.02.543519 (2023).

Lee, E. et al. Web Apollo: a web-based genomic annotation editing platform. Genome Biol 14, R93, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2013-14-8-r93 (2013).

Shumate, A. & Salzberg, S. L. Liftoff: accurate mapping of gene annotations. Bioinformatics https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa1016 (2020).

Stanke, M. & Morgenstern, B. AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene prediction in eukaryotes that allows user-defined constraints. Nucleic Acids Res 33, W465–467, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gki458 (2005).

Warrenfeltz, S., Kissinger, J. C. & EuPath, D. B. T. Accessing Cryptosporidium Omic and Isolate Data via CryptoDB.org. Methods Mol Biol 2052, 139–192, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-9748-0_10 (2020).

Barrnap -Bacterial ribosomal RNA predictor v. 28 Apr 2018 (GitHub, 2013).

Schattner, P., Brooks, A. N. & Lowe, T. M. The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 33, W686–689, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gki366 (2005).

Conesa, A. et al. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 21, 3674–3676, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610 (2005).

Paysan-Lafosse, T. et al. InterPro in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res 51, D418–D427, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac993 (2023).

Ifeonu, O. O. et al. Annotated draft genome sequences of three species of Cryptosporidium: Cryptosporidium meleagridis isolate UKMEL1, C. baileyi isolate TAMU-09Q1 and C. hominis isolates TU502_2012 and UKH1. Pathog Dis 74 https://doi.org/10.1093/femspd/ftw080 (2016).

Anaconda Software Distribution v. 2-2.4.0 (2016).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods 12, 59–60, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3176 (2015).

Sun, J. et al. OrthoVenn3: an integrated platform for exploring and visualizing orthologous data across genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 51, W397–W403, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad313 (2023).

Krzywinski, M. et al. Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res gr.092759.109 [pii] (2009).

Chen, C. et al. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol Plant 13, 1194–1202, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009 (2020).

Chu, J. JupiterPlot: A Circos-based tool to visualize genome assembly consistency (1.0). Zenodo (2018).

Penumarthi, L. R., Baptista, R. P., Beaudry, M. S., Glenn, T. C. & Kissinger, J. C. A new chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of Cryptosporidium meleagridis NCBI SRA. http://identifiers.org/insdc.sra:SRR27282542 (2024).

Penumarthi, L. R., Baptista, R. P., Beaudry, M. S., Glenn, T. C. & Kissinger, J. C. A new chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of Cryptosporidium meleagridis NCBI BioProject http://identifiers.org/bioproject:PRJNA1022047 (2024).

Penumarthi, L. R., Baptista, R. P., Beaudry, M. S., Glenn, T. C. & Kissinger, J. C. A new chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of Cryptosporidium meleagridis NCBI Nucleotide http://identifiers.org/insdc:JBCHVM000000000 (2024).

Hulsen, T., Huynen, M. A., de Vlieg, J. & Groenen, P. M. Benchmarking ortholog identification methods using functional genomics data. Genome Biol 7, R31 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by NIH R01AI14866 to JCK and TCG.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.R.P. performed analyses and wrote the manuscript; J.C.K., R.P.B. and T.C.G. conceived the study; R.P.B., M.S.B., and L.R.P. generated the genome assembly and L.R.P. and R.P.B. performed annotation; L.R.P., J.C.K., R.P.B. and M.S.B. edited the manuscript; T.C.G. and J.C.K. provided oversight and funding; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Penumarthi, L.R., Baptista, R.P., Beaudry, M.S. et al. A new chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of Cryptosporidium meleagridis. Sci Data 11, 1388 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04235-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04235-7