Abstract

Climate classification systems (CCSs) are emerging as essential tools in climate change science for mitigation and adaptation. However, their limitations are often misunderstood by non-specialists. This situation is especially acute when the CCSs are derived from Global Climate Model outputs (GCMs). We present a set of uncertainty maps of four widely used schemes -Whittaker-Ricklefs, Holdridge, Thornthwaite-Feddema and Köppen- for present (1980–2014) and future (2015–2100) climate based on 52 models from the Coupled Intercomparison Model Project Phase six (CMIP6). Together with the classification maps, the uncertainty maps provide essential guidance on where the models perform within limits, and where sources of error lie. We share a digital resource that can be readily and freely integrated into mitigation and adaptation studies and which is helpful for scientists and practitioners using climate classifications, minimizing the risk of pitfalls or unsubstantiated conclusions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Climate classification systems (CCSs) are valuable tools for societal and environmental applications1,2,3. They simplify complex, multidimensional climate data by transforming continuous variables, such as temperature and precipitation, into discrete categories that are meaningful for ecological purposes. This process, known as dimension reduction, creates a user-friendly format that facilitates the identification of broad patterns between climate drivers and the spatial distribution of biota. Used together with climate model outputs, CCSs provide a neat description of the past and future climate change4,5,6,7.

A significant limitation of CCSs, however, is that their ability to accurately define climate zones depends on the quality of the input data. If these are uncertain, the resulting product is compromised. End users assume these uncertainties are monitored by the developers of CCSs and that their impact on the final product is limited, giving a false sense of confidence8.

Most CCSs are built using monthly and/or yearly data from two primary variables: temperature (TS) and precipitation (PR). TS is a smooth, highly spatially autocorrelated climate field. In contrast, PR exhibits high spatial variability, making it challenging to measure and predict. Indeed, errors exceeding 100% are not uncommon for precipitation data9. Given the many difficulties in capturing the true nature of precipitation, it has unsurprisingly become the primary source of uncertainty and bias in CCSs, potentially limiting the reliability of the analysis derived from these datasets10.

Our goal is to provide both practitioners and researchers from a variety of disciplines -e.g., biologists, geographers, and ecologists- with the tools and datasets they need for accurate environmental analysis based on the current knowledge of state-of-the-art Global Climate Models (GCMs). A key element is that of consensus maps, as defined by Navarro et al.10. These maps, along with their corresponding classification maps, synthesize information from multiple models to reveal areas of agreement (or disagreement) according to present and future climate types (Fig. 1). This comprehensive view allows users to navigate potential pitfalls in their analyses and ensure robust research.

Global distribution of climate zones for the four CCSs for the SSP5-8.5 future scenario (a,c,e,g). Consensus maps of climate zones for the top-10 ensemble mean (b,d,f,h). Colors represent the degree of confidence: dark blue (≥80%), light blue (79-60%), yellow (59-40%), light red (39-20%), and dark red (<20%). The stripes show the regions with low class agreement.

This analysis leverages output from top-ranked GCMs to explore future climate conditions through the lens of four well-known climate classification systems: Whittaker-Ricklefs biomes, Köppen’s climate types, Thornthwaite-Feddema climate classification, and Holdridge’s life zones. While Köppen is dominant11,12,13, the other CCSs offer valuable and often more nuanced perspectives on the complex relationship between climate and environment, each tailored to the needs of specific audiences14,15,16.

Methods

Climate Classification Systems

The main four CCSs used in the literature are included: 1. Holdridge’s life zones17; 2. Köppen climate types18; 3. Thornthwaite’s classification19; 4. Whittaker’s biomes20.

Holdridge life zones are defined by three measurements: annual precipitation (mm·year−1), biotemperature (°C) and potential evapotranspiration (PET) ratio. Annual precipitation is calculated from monthly precipitation data. Mean annual biotemperature is derived from monthly average temperature. Those months with a mean temperature above 30.0 °C and below 0.0 °C are considered as 30.0 °C and 0.0 °C, respectively. PET ratio is defined as the mean annual biotemperature multiplied by a constant value (58.93) and divided by annual precipitation. We assign a class to each grid cell by computing the minimum Euclidean distance between each pixel and the geometric centroids of life zones, as defined in Sisneros et al.21. The 33 classes are then grouped into 13 categories as shown in Table 1.

For the Köppen scheme, we followed the work of Lohman et al.22, which is based on Köppen’s early work. In this seminal publication, ecoregions are divided into five climate types, four thermal types (A, C, D, E), and one hydrologic type (B). In addition, the scheme includes three subtypes (f, s, w) related to the annual cycle of precipitation. Operationally, the classification algorithm works as follows: first, it evaluates the precipitation threshold. Second, it processes climate types A, C, D and E, respectively. This workflow ensures a consistent identification of arid climates23. Otherwise, discrepancies may arise. While this is not a problem when only models are compared (as in Tapiador et al.24), it will certainly yield paradoxes if observations are used. The defining criteria of each climate type are shown in Table 2.

We used the revised version of Thornthwaite’s classification proposed by Feddema25, which has become standard practice in the field. Similar to the original work, it centers on the concept of water availability. However, this revision incorporates a simplified version of the moisture state, as defined by Willmott and Feddema26. Moisture Index Im ranges from −1 to 1 and is defined as follows: \({I}_{m}=\left\{\begin{array}{c}\left(r/{PE}\right)-1,r < {PE}\\ 1-\left({PE}/r\right),r\ge {PE}\end{array}\right.\) where r is the annual rainfall and PE is potential evapotranspiration. The thermal component remains faithful to the classic definition of potential evapotranspiration developed by Thornthwaite. Table 3 shows the criteria defining the 36 climate types.

We followed the delineation of Whittaker’s biomes as described by Ricklefs27. The scheme divides the Earth into nine biomes according to annual precipitation (cm·year−1) and annual mean temperature (oC). The biome distribution criteria are shown in Fig. 2.

Classification for this case was performed using the R package plotbiomes28. Outliers were assigned the climate type of the closest biome.

Climate data

Climate classification maps and consensus maps were constructed using monthly precipitation and temperature from 52 models of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase 6 (CMIP6)29. CMIP6 data are publicly available and have been downloaded from the Earth System Grid Federation node (https://aims2.llnl.gov/search). The dataset included both the current climate (1980–2014) and future projections (2021–2050, 2051–2100, 2015–2100). To explore a range of future scenarios, we incorporated data from three Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs)30: SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5. The three choices are intended to be comprehensive and cover the vast majority of needs of adaptation and mitigation studies. Finally, to ensure consistency, all datasets were interpolated to a common horizontal resolution of 1° × 1°, using bilinear interpolation. This choice aligns with the native resolution of most CMIP6 models and minimizes potential uncertainties introduced by downscaling to finer resolutions, which is critical for developing consensus maps. The analysis was for land-only, excluding Antarctica. The full list of models can be found in Supplementary Information (Table S1).

Model rank and top-10 ensemble members

We used Cohen’s kappa coefficient31 to quantify the ability of each model to reproduce the distribution of climate categories. This standard method is widely used to gauge model quality. Present reference climate is also the standard choice: it is calculated using the Climate Research Unit Time Series (CRU, version 4.0432) observations for each CCS for the historical climatological period (1980–2014). The kappa coefficient (κ) is defined as follows: \({\rm{\kappa }}=\frac{{P}_{0}-{P}_{e}}{1-{P}_{e}}\), where P0 is the proportion of units with agreement and Pe is the hypothetical probability of chance agreement. The kappa statistic ranges from 0 to 1, with 0 meaning no agreement and 1 meaning perfect agreement.

Models were also ranked in terms of joint agreement with precipitation and temperature observations. The metric used for these quantitative variables was the coefficient of determination R2. The reason for using this metric is twofold: first, it has been shown to be useful for comparing large-scale means of climate data, such as those used by most climate classification schemes15. Second, it condenses information into a single, easy-to-interpret value, thus facilitating comparisons between models. Grid boxes were weighted by area in both metrics. We then identified the best performing models by focusing on the upper right quadrant of a 2D plane (Fig. 3). This quadrant represents models with both high class agreement (κ) and high precipitation scores (R²). The median values of κ and R² (precipitation) were used to define the boundaries. Finally, we selected the top-10 models within this quadrant based on the highest κ scores.

Scores of CMIP6 models for the four classification schemes: (a) Holdridge, (b) Köppen, (c) Thornthwaite-Feddema, (d) Whittaker-Ricklefs. Dots are individual CMIP6 models (52 models + 2 ensemble means). The y axis is the R2 score for global precipitation (mm·year−1), x axis is the kappa coefficient of each CCS and colors are the R2 score for global mean temperature. Dotted grey lines are the median. Zoomed areas indicate the region of best performance, and models within this area are then selected to create the top-10 ensemble mean (T10). Numbers in black are the top 10 models, while the other models are in grey. The red number is the T10 ensemble mean, and the blue one is the 52-model ensemble mean. The analysis was performed for the 1980–2014 period.

Table 4 shows the scores for the top-10 models for Whittaker’s scheme. For the remaining CCSs, see Tables S2–S4 in the Supplementary Information document.

Uncertainty analysis

Model uncertainties are embedded in the so-called consensus maps (Fig. 4). Consensus maps provide a qualitative description of model uncertainties, highlighting regions where models disagree. Quantitatively, these maps are built on two key metrics derived from pixel-by-pixel comparisons: percent confidence and inter-model class agreement.

Graphical description of the uncertainty estimation of distributed climate zones. (a) Maps of climate types for top-10 models and reference data. (b) The performance of individual models was evaluated against the reference data in a pixel-by-pixel comparison, and the degree of agreement between reference and models (in percent) was then calculated. Each pixel is colorized in the consensus map according to the level of confidence: dark blue (≥80%), light blue (79-60%), yellow (59-40%), light red (39-20%), and dark red (<20%). (c) Inter-model class agreement, which represents the number of different climate types identified by the top-10 models for each pixel. Two or fewer climate types indicates low inter-model variability, while three or more indicates high variability (striped regions in the consensus map). The analysis was performed for the four climate classification schemes. Reference data is CRU (for present) and T10 ensemble mean (for future scenarios).

The first metric (Fig. 4b) quantifies the accuracy of individual models relative to observed climate types. The formulation is as follows: \({{\rm{Confidence}}}_{i,j}=\frac{{{coincident\; models}}_{i,j}}{{{Nmodels}}_{i,j}}\cdot 100\), where the fraction represents the proportion of models, for each pixel (i,j), that predicted a climate class matching the reference data. Here, coincident models refers to the number of models with matching climate type, and Nmodels represents the total number of models considered. Confidence levels were discretized into five categories: very high (≥80%), high (79%- 60%) moderate (59%-40%), low (39%-20%), and very low (<20%). The second metric evaluates inter-model variability, i.e. how many climate types are identified by different models for the same point in space. For example, Fig. 4c shows that for a given pixel at (i,j), four models defined the region as woodland, three as temperate desert, and the other three as boreal forest. This results in three different climate types, which implies low inter-model agreement. Both metrics are complementary, the first metric shows the accuracy while the second measures the dispersion (precision). Uncertainty maps were constructed for each CCS for the present and the three SSPs, using the CRU and the top-10 ensemble, respectively, as reference.

Data Records

Global datasets of the four CCSs and their associated consensus maps for present and future climates are available at Figshare33. The data are provided in three different file formats to meet the needs of a wide range of users. All datasets have a spatial resolution of 1°, which corresponds to 180 × 360 pixels. For ease of download, individual files within the same format are combined into a single tar.gz archive.

-

1.

GeoTIFF files are for general users who want an immediate image of the distribution of climate types and consensus maps. The compressed file contains 120 GeoTIFF files accompanied by a legend (legend.txt) that defines the code categories used in each climate classification system (13 for Holdridge, 11 for Köppen, 36 for revised Thornthwaite and 9 for Whittaker’s biomes). The filename structure is: classification_varname_scenario_period.tif (e.g koppen_confidence_historical_1980-2014.tif, whittaker_class_ssp126_2051-2100.tif, and koppen_modvar_ssp585_2021-2050.tif). Class refers to climate classification, confidence is percent confidence, and modvar refers to inter-model variability.

-

2.

NetCDF files are for more advanced users. They can be directly read in a Geographic Information System (GIS) such as QGIS. A major advantage is that they are self-describing files, meaning the data and its metadata are stored together in a single file. The tar.gz includes 80 nc files. The files including climate classification maps also include their respective key variables, except for Köppen. For example, the file whittaker_class_historical_1980-2014.nc contains data for annual mean temperature (AT, in oC), annual precipitation (APP, in cm·year-1), and Whittaker’s climate classification itself. Similarly, holdridge_class_ssp245_2051–2100.nc includes biotemperature (ABT, in oC), annual precipitation (APP, in mm·year−1), potential evapotranspiration ratio (PER) and Holdridge’s life zones (HLZ) for the future scenario SSP2-4.5 and the period 2051-2100. Files of consensus maps, like holdridge_consensus_ssp585_2021-2050.nc, store the following variables: confidence and modvar. Codes for the classification categories are embedded within the file’s attributes for easy reference.

-

3.

BIL, pure binary files are suited for fast reading and efficient computation. The compressed file contains 120 bil files, along with the corresponding header files (hdr) and a legend file (legend.txt). They can also be directly read in a GIS. The dimensions of each bil file are 180 × 360. Filenames follow the same naming convention as tiff files.

The data are based on the top-10 ensemble mean, although we performed the calculations for the 52 CMIP6 models. Data for individual models and the MME (52) are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Technical Validation

Model validation

Climate classifications derived from GCMs were validated against observations from the Climate Research Unit (CRU at the University of East Anglia) Time Series version 4.0432. The CRU dataset has 0.5° spatial resolution but was aggregated to 1°, following the same procedure as for the CMIP6 models. The validation was performed for three variables: annual precipitation, mean annual temperature, and climate classes. Figure 3 shows the scores of individual models, as well as ensemble means -MME (52) and top-10 ensemble- for the 1980–2014 period. Alternative ensemble sizes (top-20, top-30 and top-40) were also evaluated, but their performance did not show consistent improvement over top-10 and MME. As illustrated in the figure, global performance varies depending on the climate classification scheme. Whittaker’s biomes achieve the highest overall scores (κ = 0.74), while Thornthwaite’s shows the lowest scores (κ = 0.42) for the MME (52). Eight individual GCMs/ESMs consistently achieve the highest scores across all CCSs: CESM2, EC-Earth-Veg-LR, HadGEM3-GC31-LL, HadGEM3-GC31-MM, MRI-ESM2-0, NorESM2-MM, TaiESM1 and UKESM1-0-LL. This is likely because they perform better at simulating precipitation, a key source of bias in CCSs10. For mean temperature, all models obtained scores above R2 = 0.95.

Uncertainty analysis of reference data

Observational data often have differences that can affect the representation of climate zones. To assess this sensitivity, we evaluated climate classifications using alternative datasets in addition to CRU. These included station-based data from the University of Delaware (UDEL version 5.0134) and the Global Precipitation Climatology Centre (GPCC) Full Data Monthly Product version 202235,36, as well as the ECMWF’s reanalysis data37,38 (ERA5).

A classification scheme that is insensitive to these variations is considered robust to observational uncertainties39. Figure 5 illustrates this concept, showing small changes in the global distribution of climate types.

Percentage of continental area covered by each climate type for the four climate classification schemes (Köppen, Holdridge, Thornthwaite-Feddema, and Whittaker-Ricklefs) and the four observational datasets (CRU, GPCC, UDEL and ERA5). Classification schemes for GPCC are a combination of data from the GPCC (precipitation) and CRU (temperature).

CRU and GPCC show the greatest agreement (1.3% to 1.6% of the discrepancy in total land area) for Holdridge, Köppen, and Whittaker classifications. UDEL also has relatively small discrepancies (1.5% to 3.1%), while ERA5 displays slightly larger differences (3.6% to 7.3%). Thornthwaite’s scheme shows the greatest sensitivity to data source. Here, ERA5 predicts a shift in high-latitude climates, with cold-wet types becoming more common at the expense of cold-moist types.

Usage Notes

The dataset offers a comprehensive description of current and future global climate, based on four major classification schemes. We provide maps for Holdridge, Köppen, Thornthwaite-Feddema, and Whittaker-Ricklefs climate classifications along with their corresponding consensus maps. Future scenarios included are SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 (three time-periods: 2021-2050, 2051-2100, and 2015-2100). The data are derived from an ensemble of the top-10 CMIP6 models (out of 52), selected based on their kappa statistic and their R2 score for precipitation. Top-10 models differ by classification scheme. Validation with observations (CRU) indicates that model outputs are reasonable. However, there are certain caveats that users may consider before using the dataset:

-

1.

We assume that current criteria for defining climate types are the same for future climate, leaving no room for new equilibrium conditions or new climate types. This is a common issue in any rule-based classification scheme40,41.

-

2.

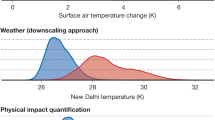

Our maps have a 1° spatial resolution, which is the native resolution of most CMIP6 models. While it might be deemed low for certain regional applications, it is worth noting that kilometer or even hectometer resolutions are the result of interpolations well below the resolution of the original empirical data. Indeed, there is no limit for downscaling a scalar field; the only question is what is sacrificed in the mathematical process. By keeping the spatial resolution at the nominal model grid size, we avoid introducing additional uncertainties associated with downscaling techniques, and ensure that the final product reflects the inherent resolution of the underlying climate models.

-

3.

Model performance is contingent to the classification scheme. As shown in Fig. 3, individual models and ensemble means presented different scores, according to the CCS. While models performed well for Köppen (11 cats), Holdridge (13 cats), and Whittaker (9 cats), the performance for Thornthwaite (36 cats) was moderate, meaning that their maps should be used with caution.

-

4.

All four CCSs are primarily based on precipitation and temperature. However, each CCS was developed with distinct goals and criteria, leading to variations in how they identify regions undergoing climate change.

-

5.

Consensus maps depict the confidence of model predictions pinpointing regions where consensus is lacking. While many of such regions overlap across CCSs, some disagreements arise, specifically at the boundary of climate types, as defined by each unique classification scheme. Additionally, the degree of consensus may vary depending on the socio-economic scenario chosen.

Code availability

The codes for the CCSs and consensus maps are available on GitHub at https://github.com/navarro-esm/uncertainty_maps_library. The source code of Whittaker’s biomes is available from https://github.com/valentinitnelav/plotbiomes.

References

Kummu, M., Heino, M., Taka, M., Varis, O. & Viviroli, D. Climate change risks pushing one-third of global food production outside the safe climatic space. One Earth 4, 720–729 (2021).

Watson, L. et al. Global ecosystem service values in climate class transitions. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 024008 (2020).

Zhang, M. & Gao, Y. Time of emergence in climate extremes corresponding to Köppen-Geiger classification. Weather Clim. Extrem. 41, 100593 (2023).

Chen, D. & Chen, H. W. Using the Köppen classification to quantify climate variation and change: An example for 1901–2010. Environ. Dev. 6, 69–79 (2013).

Feng, S. et al. Projected climate regime shift under future global warming from multi-model, multi-scenario CMIP5 simulations. Global Planet. Change 112, 41–52 (2014).

Willmes, C., Becker, D., Brocks, S., Hütt, C. & Bareth, G. High Resolution Köppen-Geiger Classifications of Paleoclimate Simulations. T. GIS 21, 57–73 (2017).

Zhang, X., Yan, X. & Chen, Z. Geographic distribution of global climate zones under future scenarios. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4327–4334 (2017).

Beck, H. E. et al. Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Scientific Data 5, 180214 (2018).

Tapiador, F. J. et al. Is Precipitation a Good Metric for Model Performance? B. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 100, 223–233 (2019).

Navarro, A., Lee, G., Martín, R. & Tapiador, F. J. Uncertainties in measuring precipitation hinders precise evaluation of loss of diversity in biomes and ecotones. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 35 (2024).

Beck, H. E. et al. High-resolution (1 km) Köppen-Geiger maps for 1901–2099 based on constrained CMIP6 projections. Scientific Data 10, 724 (2023).

Cui, D., Liang, S. & Wang, D. Observed and projected changes in global climate zones based on Köppen climate classification. WIREs Clim. Change 12, e701 (2021).

Peel, M. C., Finlayson, B. L. & McMahon, T. A. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sc. 11, 1633–1644 (2007).

Elguindi, N., Grundstein, A., Bernardes, S., Turuncoglu, U. & Feddema, J. Assessment of CMIP5 global model simulations and climate change projections for the 21stcentury using a modified Thornthwaite climate classification. Climatic Change 122, 523–538 (2014).

Tapiador, F. J., Moreno, R., Navarro, A., Sánchez, J. L. & García-Ortega, E. Climate classifications from regional and global climate models: Performances for present climate estimates and expected changes in the future at high spatial resolution. Atmos. Res. 228, 107–121 (2019).

Zhao, X., Yang, Y., Shen, H., Geng, X. & Fang, J. Global soil–climate–biome diagram: linking surface soil properties to climate and biota. Biogeosciences 16, 2857–2871 (2019).

Holdridge, L. R. Determination of World Plant Formations From Simple Climatic Data. Science 105, 367–368 (1947).

Köppen, W. Versuch einer Klassifikation der Klimate, vorzugsweise nach ihren Beziehungen zur Pflanzenwelt. Geogr. Z. 6, 657–679 (1900).

Thornthwaite, C. W. An Approach toward a Rational Classification of Climate. Geogr. Rev. 38, 55–94 (1948).

Whittaker, R. H. Communities and Ecosystems. (Macmillan, New York, 1975).

Sisneros, R., Huang, J., Ostrouchov, G. & Hoffman, F. Visualizing Life Zone Boundary Sensitivities Across Climate Models and Temporal Spans. Procedia Comput. Sci. 4, 1582–1591 (2011).

Lohmann, U. et al. The Köppen climate classification as a diagnostic tool for general circulation models. Clim. Res. 3, 177–193 (1993).

Rohli, R. V., Joyner, T. A., Reynolds, S. J., Shaw, C. & Vázquez, J. R. Globally Extended Kӧppen–Geiger climate classification and temporal shifts in terrestrial climatic types. Phys. Geogr. 36, 142–157 (2015).

Tapiador, F. J., Moreno, R. & Navarro, A. Consensus in climate classifications for present climate and global warming scenarios. Atmos. Res. 216, 26–36 (2019).

Feddema, J. J. A Revised Thornthwaite-Type Global Climate Classification. Phys. Geogr. 26, 442–466 (2005).

Willmott, C. J. & Feddema, J. J. A More Rational Climatic Moisture Index. Prof. Geogr. 44, 84–88 (1992).

Ricklefs, R. E. The Economy of Nature. (W.H. Freeman and Co., New York, NY, 2008).

Ștefan, V. & Levin, S. Source code for: plotbiomes: R package for plotting Whittaker biomes with ggplot2. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7145245 (2018).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. A new scenario framework for climate change research: the concept of shared socioeconomic pathways. Climatic Change 122, 387–400 (2014).

Cohen, J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educ. Psychol. Measurement 20, 37–46 (1960).

Harris, I., Osborn, T. J., Jones, P. & Lister, D. Version 4 of the CRU TS monthly high-resolution gridded multivariate climate dataset. Scientific Data 7, 109 (2020).

Navarro, A., Merino, A., García-Ortega, E., & Tapiador, FJ. Uncertainty maps for model-based global climate classification systems, Figshare, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28071410 (2025).

Matsuura, K. & Willmott, C.J. Terrestrial Air Temperature and Precipitation: Monthly and Annual Time Series (1900–2014). https://climate.geog.udel.edu/ (2015).

Schneider, U. et al. GPCC’s new land surface precipitation climatology based on quality-controlled in situ data and its role in quantifying the global water cycle. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 115, 15–40 (2014).

Schneider, U. et al. GPCC Full Data Monthly Product Version 2022 at 1.0°: Monthly Land-Surface Precipitation from Rain-Gauges built on GTS-based and Historical Data. Global Precipitation Climatology Centre at Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD). https://doi.org/10.5676/DWD_GPCC/FD_M_V2022_100 (2022).

Hersbach, H. et al. ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Hersbach, H. et al. ERA5 monthly data on single levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.f17050d7 (2024).

Phillips, T. J. & Bonfils, C. J. W. Köppen bioclimatic evaluation of CMIP historical climate simulations. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 064005 (2015).

Netzel, P. & Stepinski, T. On using a clustering approach for global climate classification. J. Climate 29, 3387–3401 (2016).

Sanderson, M. The Classification of Climates from Pythagoras to Koeppen. B. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 80, 669–673 (1999).

Monserud, R. A. & Leemans, R. Comparing global vegetation maps with the Kappa statistic. Ecol. Model. 62, 275–293 (1992).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación and Agencia Estatal de Investigación, MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, ERDF A way of making Europe and the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR (Projects: PID2022-138298OB-C22, PID2022-138298OB-C21, PDC2022-133834-C21, TED2021-131526B-I00). A.N. also acknowledges the financial support of the Regional Government of Castilla-La Mancha and the European Social Fund Plus (SBPLY/22/180502/000019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.N.: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing, review & editing, funding acquisition. E.G.O.: formal analysis, methodology, writing, funding acquisition. A.M.: formal analysis, methodology, visualization, writing, funding acquisition. F.J.T.: formal analysis, investigation, writing, review & editing, funding acquisition, supervision. All authors substantially contributed to the article and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Navarro, A., Merino, A., García-Ortega, E. et al. Uncertainty maps for model-based global climate classification systems. Sci Data 12, 35 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04387-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04387-0