Abstract

Deforestation-induced forest loss largely affects both the carbon budget and ecosystem services. Subsequent forest regrowth plays a crucial role in ecosystem restoration and carbon replenishment. However, there is an absence of comprehensive datasets explicitly delineating the forest regrowth following deforestation. Here we employed multiple remotely sensed datasets to generate the first dataset capturing forest structural regrowth, including forest height, aboveground biomass (AGB), leaf area index (LAI), and fraction of photosynthetically active radiation (FPAR), subsequent to deforestation in globally key deforestation regions at a 30 m spatial resolution. The regrowth index for each structural parameter includes regrowth ratios and rates at 5-year intervals spanning primarily from 1985 to 2020. This dataset provides a nuanced understanding of forest regrowth following deforestation across spatial, temporal, and structural scales, thereby facilitating accurate quantification of forest carbon budget and enhancing assessments of forest ecological services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Forest loss due to deforestation occurs in various regions around the world1,2,3. It exerts significant impacts on the forest carbon budget4 and also affects ecosystem services such as the conservation of biodiversity. Following such loss, forest recovery, including natural regrowth and tree plantation initiatives, plays a pivotal role in ecosystem restoration and carbon sequestration5,6. For example, naturally regenerated forests have been found to sequester significant carbon stock7 and harbor diverse tree species8. However, the efficacy and impacts of this restoration process depend not only on the extent of forest recovery but also on the magnitude of new forest growth9. Hence, there is a pressing need for a comprehensive assessment of the spatial, temporal, and structural aspects of secondary forest growth subsequent to deforestation events. Such insights are vital for understanding the status of forest ecosystems and devising effective forest management policies.

Satellite-based remotely sensed datasets are extensively applied to monitor large-extent forest change1,2,10,11. Nevertheless, existing datasets often focus on spatial extent rather than vertical forest structure, such as forest height. In recent years, there has been rapid development in satellite sensor technology, offering improved capabilities for acquiring detailed forest structure information. For instance, Potapov, et al.12 mapped global forest canopy height at 30 m spatial resolution through integration of Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI) footprint-level height measurements13 and global Landsat analysis-ready data. However, there remains a gap in datasets that integrate both spatial extent and structural information regarding forest regrowth following deforestation. Meanwhile, historical maps of forest structure are incomplete, with global forest height products at a resolution finer than 100 m available for 2000, 2019, and 202012,14, and global forest aboveground biomass (AGB) products available for 2010 and from 2017 to 202015. This poses challenges for explicitly characterizing forest regrowth conditions throughout all stages.

In this study, we aim to generate forest regrowth maps for multiple structural parameters across globally key deforestation regions from 1985 to 2020. We utilized forest dynamics datasets, including forest cover, deforestation, and plantation data, alongside forest structure parameter datasets such as forest height, AGB, leaf area index (LAI), and fraction of photosynthetically active radiation (FPAR). Regional age-height models for secondary forest growth were developed, and regional height-AGB allometric equations were employed to reconstruct historical maps of secondary forest height and AGB for years without available data. Subsequently, we designed and calculated indices such as regrowth ratio and regrowth rate to characterize the regrowth conditions of these four forest structure parameters.

Methods

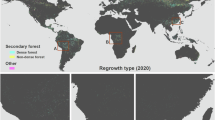

We define deforestation as stand-replacement deforestation, including forestry, bioenergy-driven harvest, and commodity-driven deforestation. Globally, approximately 70% of the forests are distributed in tropical, subtropical, and temperate zones, where deforestation occurs most frequently16. Our study focuses on the most representative regions within these zones, including key regions of North America, South America, and Africa, as well as the entire regions of Europe, Northeast China, and Southeast Asia (Fig. 1).

Study area and workflow for generating the forest regrowth dataset. The study area includes key regions of North America (A), South America (D), and Africa (E), as well as the entire regions of Europe (B), Northeast China (C), and Southeast Asia (F). Abbreviations used in the figure are: forest disturbance with different land use drivers (FDD), global forest change (GFC), continuous monitoring of land disturbance (COLD), tropical moist forests (TMF), forest/non-forest (FNF). The data or algorithm indicated by these abbreviations are explained in detail in the subsequent sections.

Figure 1 also presents the workflow for generating the forest regrowth dataset. Specifically, we have: (1) obtained the corresponding deforestation areas for each region through extraction from existing datasets or independent production; (2) identified secondary forest areas following deforestation using forest cover and plantation datasets; (3) developed regional age-height models for secondary forest growth by linking forest height and regrowth time to generate historical secondary forest height maps; (4) produced historical secondary forest AGB maps based on the secondary forest height maps using regional forest height-AGB allometric equations; (5) mapped time-series forest regrowth ratios and rates for secondary forest height and AGB; (6) mapped time-series forest regrowth ratios and rates for secondary forest LAI and FPAR using the available long-term time series datasets of forest LAI and FPAR.

Data preprocessing

Deforestation dataset

The European Commission’s Joint Research Centre primarily used Landsat imagery to develop a new dataset of forest cover change in tropical moist forests (TMF) at 30 m resolution from 1982 to 20222. This dataset depicts the extent of deforestation and post-deforestation recovery in TMF, and records the time of each deforestation event. The TMF primarily includes tropical rainforests and tropical moist deciduous forests as defined by the ecological zones adopted by the Food and Agriculture Organization. The performance of their forest disturbance detection results in 9.4% omissions, 8.1% false detections, and 91.4% overall accuracy. For the forest identification, the producer’s and user’s accuracies are 92.3% and 90.8%, respectively2. Based on the recorded deforesting year, we calculated the regrowth time following the deforestation in South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia at the pixel scale for year 2020.

Using high-resolution Google Earth imagery, Curtis, et al.17 developed a forest loss classification model to determine a global distribution of forest disturbance with different land use drivers (FDD) at 10 km × 10 km grid cell over the period 2001 to 2015. They assigned the category of the driver for each grid cell according to the dominant disturbance type. The producer’s and user’s accuracies for the classification of commodity-driven deforestation are 94% and 85%, respectively17. We used the distribution of the commodity-driven deforestation in North America from this data as a mask to extract the extent of 30-m resolution annual forest loss map from global forest change (GFC) dataset1 during the same period. The producer’s and user’s accuracies of the GFC forest loss map are 87.8% and 87.0%, respectively1. This resulted in the extent and year of the commodity-driven deforestation from 2001 to 2015 in North America at 30 m resolution. Then, we calculated the regrowth time following the deforestation in North America for year 2020 based on the deforesting year.

In Europe, we referred to the practice of Ceccherini, et al.3 to derive the deforestation areas. Ceccherini, et al.3 assumed that the forest loss detected by the GFC maps is a reasonable proxy for the harvested forest area after removing losses related to wildfires or major windstorms. Following this, we utilized both the global 30-m resolution satellite-based map of forest loss due to fire (2000–2019)18 and the delineation of stand-replacing windthrow events (1986–2017) in the forest zone of European Russia19 to exclude the wildfire and major windstorm areas from the GFC forest loss map, and then derived a representative extent of the deforestation from 2001 to 2019 in Europe at 30 m resolution. Producer’s and user’s accuracies of the forest fire classification in Europe are 88% and 85%, respectively18. Similarly, we calculated the regrowth time following the deforestation in Europe for same years as in North America based on the deforesting year.

In Northeast China, we detected deforestation from 1986 to 2019 using the continuous monitoring of land disturbance (COLD) algorithm20 based on Landsat time-series data. COLD is an enhancement of the continuous change detection and classification (CCDC) algorithm21 for forest disturbance, and it utilizes the normalized change magnitude for six consecutive observations exceeding the chi-squared distribution of a change threshold to identify a forest disturbance. Based on a total of 3187 reference forest disturbance samples interpreted (Fig. S1) by using the same method as described in Shang, et al.22, the detected forest disturbances were then classified into four types by using Random Forest Model23: Deforestation, Wildfire, Insect and disease, and Others. The inputs of the model include the detected results from the COLD algorithm (change magnitude, root-mean-squared error (RMSE), pre- and post-disturbance harmonic model coefficients), topographic data (digital elevation model (DEM), slope, aspect), spectral indices before and after disturbance (NBR24, NDVI25) and their change magnitudes, as well as the textural features of the disturbance patches. 50% of reference forest disturbance samples were randomly selected for model training, and the remaining samples were used for validation. The accuracy indicated by F1-score26 is 94.11% for Deforestation (with a commission error of 5.33% and an omission error of 6.45%). For areas with multiple deforestations, we selected the last time of the deforestation as the beginning time of the forest regrowth. Finally, we calculated the regrowth time following the deforestation in Northeast China at the pixel scale for year 2020 based on the deforesting year.

Forest cover and plantation dataset

Shimada, et al.27 generated global forest/non-forest map (FNF) through classifying the Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) image (backscattering coefficient) in the global 25-m resolution Phased-Array L-band Synthetic Aperture Radar (PALSAR) and Phased-Array L-band Synthetic Aperture Radar - 2 (PALSAR-2) SAR mosaic so that strong and low backscatter pixels are assigned as forest and non-forest, respectively. The accuracy assessments indicated the overall agreement of 85%, 91% and 95% against the Degree Confluence Project, the Forest Resource Assessment, and high-resolution Google Earth images, respectively27. This dataset has been updated to cover the time range from 2007 to 2020. Before utilizing the FNF map, we aggregated the pixels to 30 m resolution using the averaging method to align with that of the deforestation map. On the other hand, Du, et al.28 produced a global map of planting years for plantations using a Landsat-based detection of Trends in Disturbance and Recovery (LandTrendr) algorithm29 on the basis of global plantation extent products. This map provides the latest planting years for plantations from 1982 through 2019 at 30 m resolution based on the plantation extent. Compared to the results in Danylo, et al.30, the F1 score for each year of this map was relatively high (78.25%) when the deviation was allowed within ± 3 years and 86.83% with ± 5 years28. We extracted partial plantation extents referencing to the deforesting time range for three northern regions, including: (1) the extent with planting time from 2001 to 2019 in North America, (2) the extent with planting time from 2001 to 2019 in Europe, and (3) the extent with planting time from 1986 to 2019 in Northeast China.

LAI and FPAR dataset

Ma and Liang31 and Ma, et al.32 utilized deep learning methodologies to produce updated versions of LAI and FPAR products (V6) at 250 m resolution using surface reflectance data of Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) spanning from 2000 to present. LAI and FPAR medians at the pixel scale from all available maps within a year were computed to represent the LAI and FPAR values for that year. Subsequently, a bilinear interpolation algorithm was applied to resample them to 30 m resolution for matching the resolution of the deforestation dataset. The bilinear interpolation algorithm achieved an acceptable resampling accuracy, with an RMSE of below 0.4 in the example regions (Fig. S2). For Tropics and Northeast China, we employed the Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) LAI and PFAR datasets (1981–2013) at a resolution of 0.05° from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Climate Data Record to supplement the data before 2000. Taking LAI as an example, the consistency between these two datasets with different resolutions is reasonable, showing an RMSE of 0.33 in the United States and a slightly larger RMSE of 0.36 in Indonesia (Fig. S3). Likewise, we calculated the AVHRR LAI and FPAR medians at the pixel scale from all available maps within a year of this dataset, and resampled them to the 30 m resolution using the bilinear interpolation algorithm.

The external data utilized in this study includes: (1) the forest cover change dataset1,2,17,18,19,27,28 downloaded from https://forobs.jrc.ec.europa.eu/TMF/data, https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aau3445, https://storage.googleapis.com/earthenginepartners-hansen/GFC-2022-v1.10/download.html, https://glad.umd.edu/dataset/Fire_GFL/, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12073278.v6, https://www.eorc.jaxa.jp/ALOS/en/dataset/fnf_e.htm, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19070084.v2, respectively; (3) the forest height dataset14 accessed from https://glad.umd.edu/dataset/GLCLUC2020; (4) the LAI and FPAR dataset31,32 acquired from https://glass-product.bnu.edu.cn/ and the NOAA Climate Data Record https://doi.org/10.7289/V5M043BX, respectively.

Mapping regrowth type following deforestation

The TMF dataset provided a classification of converted land cover from the deforested land in the Tropics. The main classes of the converted land cover include naturally regenerated forests, tree plantations, water bodies, and other land cover2. Since our main focus is on secondary forest growth, we simplified these classes and merged corresponding areas into naturally regenerated forests, tree plantations, and other (combined water bodies and other land cover).

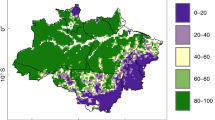

In North America, Europe, and Northeast China, we utilized existing forest cover and plantation datasets to derive the regrowth type following deforestation. We first used the forest area in FNF map for the year 2020 as a mask to identify the secondary forest recovery area and non-forest recovery area from the early deforested areas. The non-forest recovery area was assigned as “other”, signifying other various regrowth types following deforestation. The secondary forest recovery area may include naturally regenerated forests and tree plantations. Thus, we further used the plantation extent as a mask to distinguish between the tree plantations and naturally regenerated forests within the secondary forests. Figure 2 shows the three regrowth types in 2020 following deforestation.

Regrowth land type in 2020 following deforestation. (A) North America. Deforestation in this region occurred from 2001 to 2015, (B) Europe. Deforestation in this region occurred from 2001 to 2019, (C) Northeast China. Deforestation in this region occurred from 1986 to 2019, and (D–F) South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia. Deforestation in these regions occurred from 1982 to 2019.

Developing age-height model to generate historical forest height and AGB maps

Potapov., et al.14 mapped global forest canopy height (relative height 95 metrics) at 30 m spatial resolution for years 2000 and 2020 through the integration of GEDI footprint-level forest canopy height measurements and global Landsat analysis-ready data. We used the 2020 secondary forest area (comprising naturally regenerated forests and tree plantations) as a mask to extract the forest canopy height for the year 2020, resulting in a secondary forest height map for the year 2020. Due to the unavailability of forest height maps for previous years, we adopted the methodology outlined in Zang, et al.33 to estimate the secondary forest height for historical years in deforested regions. Stand age has been established as a critical factor influencing the growth of secondary forest height34,35. This methodology entails utilizing stand age and height data to develop regional age-height models for tree growth to estimate the forest height33. We assumed that the regrowth time is equivalent to the stand age. Initially, we used the secondary forest area as a mask to extract the regrowth time map for 2020, resulting in a regrowth time map for secondary forests in 2020. Subsequently, we used both the height and regrowth time maps of secondary forests in 2020 to calibrate the age-height model for secondary forest growth in each region. A total of 50,000 random points was generated for each region and valid points of them within the secondary forest area were employed to extract samples from both the height and regrowth time maps of secondary forests in 2020. The number of valid samples used for calibrating the age-height model varied across regions due to differences in secondary forest areas (Fig. 3).

In this study, we employed the exponential model, known for its effectiveness in simulating forest height growth with stand age34, to establish the relationship between the regrowth time and height of secondary forests. The best fitting results for each region are illustrated in Fig. 4, and detailed information on the fitted models is provided in Table 1. The coefficient of determination (R2) ranges from 0.43 to 0.53 and the RMSE is between 3.06 m and 4.63 m (Table 1), indicating acceptable calibration performance of the exponential models for tree growth across these regions. Additionally, these models highlight the varying growth patterns of forest height across different regions (Fig. 4).

Before estimating the secondary forest height for historical years, we first derived regrowth time maps of secondary forests for historical years in different regions from the regrowth time map of secondary forests in 2020. For example, the regrowth time map of secondary forests for the year 2015 was derived by subtracting the value of 5 from the regrowth time map of secondary forests in 2020 at the pixel scale. Pixels with negative or zero regrowth time values were considered non-forest recovery for the year and were excluded. This process resulted in regrowth time maps of secondary forests for the years 2005, 2010, and 2015 in North America and Europe, the years 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015 in Northeast China, and the years 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015 in South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia.

Utilizing the regional age-height models for secondary forest growth in deforested areas (Table 1, equations for regrowth time to height conversion), we estimated the secondary forest height at the pixel scale for historical years based on the regrowth time maps of secondary forests in each region. The dominant forest types in Table 1 and in other relevant tables were determined by referring to the vegetation type presented from Xu, et al.36 within the secondary forest areas we derived. Xu, et al.36 developed regional height-AGB allometric models by linking Lidar-derived forest heights with field inventory plot-level AGBs. The forest height samples were derived from vegetation structure observations of the spaceborne Geoscience Laser Altimeter System (GLAS) aboard the Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite (ICESat) by filtering out noisy shots with large errors. The plot-level AGB data were sourced from journal publications, listed websites, and key personnel with contact information. Subsequently, we computed the secondary forest AGB at the pixel scale for corresponding years based on the secondary forest height maps in each region using the allometric equations of Xu, et al.36 (Table 2). Each calculation at the pixel scale of the height or AGB for a specific year produced a spatially explicit map.

Mapping forest regrowth ratio following deforestation

We employed four structural parameters (height, AGB, LAI, and FPAR) to characterize forest regrowth following deforestation. In this study, the forest regrowth ratio following deforestation is defined as the ratio of a structural parameter value for a target year in secondary forests after deforestation to the corresponding value in virgin forests prior to deforestation. This ratio can be expressed as the following equation:

where \({Re\_}{{Ratio}}_{p}\) represents the regrowth ratio for a structural parameter of the secondary forest; \({{Value}}_{{p\_secondary}}\) represents the structural parameter value in secondary forests after deforestation, and \({{Value}}_{{p\_virgin}}\) represents the structural parameter value in virgin forests prior to deforestation. Before reaching the saturation of regrowth, the regrowth ratio will vary in different target years.

For North America and Europe, the forest height map for the year 2000 in Potapov., et al.14 served as the virgin forest height. In regions where forest height maps before 2000 were unavailable, we made two assumptions: (1) the virgin forest height before disturbances resembled that of nearby undisturbed forest areas, and (2) the virgin forest height did not increase over time. Consequently, we calculated the mean height values for the year 2020 within forest areas without any disturbances in each region of Northeast China, South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia as the baseline for the virgin forest height. To identify forest areas undisturbed before, we utilized the forest loss map from the GFC dataset1 in conjunction with the deforestation datasets to exclude disturbed forest areas. Meanwhile, we calculated the virgin forest AGB for each region based on the virgin forest height using the regional height-AGB allometric equations (Table 2).

For forest LAI and FPAR, we used the LAI and FPAR data for the year 200031,32 as the baseline for virgin forest LAI and FPAR in North America and Europe, and used the AVHRR LAI and FPAR data for the year 1981 as the baseline for virgin forest LAI and FPAR in Northeast China, South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia. Then, we used the regrowth time maps of secondary forests for different target years as masks to extract the LAI and FPAR maps for corresponding years, resulting in secondary forest LAI and FPAR maps for different target years in each region. Finally, we generated the height, AGB, LAI, and FPAR regrowth ratio maps of secondary forests for historical target years using Eq. (1), including maps for the years 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020 in North America and Europe, the maps for years 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020 in Northeast China, and the years 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020 in South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia. Figure 5, S4–S6 show the regrowth ratio of secondary forest height, AGB, LAI, and FPAR in 2020 following deforestation, and Figure S7 shows the historical regrowth ratios following deforestation in a typical region of South America.

Regrowth ratio of secondary forest height in 2020 following deforestation. (A) North America. Deforestation in this region occurred from 2001 to 2015, (B) Europe. Deforestation in this region occurred from 2001 to 2019, (C) Northeast China. Deforestation in this region occurred from 1986 to 2019, and (D–F) South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia. Deforestation in these regions occurred from 1982 to 2019.

Mapping forest regrowth rate following deforestation

In this study, we define the forest regrowth rate following deforestation as the rate of change of a structural parameter for a specific year in secondary forests after deforestation. According to this definition, the regrowth rates for forest height, AGB, LAI, and FPAR following deforestation can be determined through the following process:

For the regrowth rates of forest height and AGB, we first derived equations for the conversion of regrowth time to AGB based on both the regional age-height models for secondary forest growth and height-AGB allometric equations (Tables 1 and 2). Then, we obtained the derivatives of the regional age-height models for secondary forest growth and height-AGB allometric equations to derive regional regrowth rate equations for both secondary forest height and AGB with respect to the regrowth time (Table 3). Finally, we generated the maps of height and AGB regrowth rates for secondary forests for historical target years using the regional regrowth rate equations (Table 3) based on the regrowth time maps of secondary forests in each region. This includes maps for the years 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020 in North America and Europe, the years 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020 in Northeast China, and the years 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020 in South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia.

For the regrowth rate of forest LAI and FPAR, we first derived additional regrowth time maps of secondary forests for both the preceding and subsequent years of the historical target years in different regions from the regrowth time map of secondary forests in 2020. This includes the maps for the years 2004, 2006, 2009, 2011, 2014, 2016, 2019 and 2021 in North America and Europe, the years 1989, 1991, 1994, 1996, 1999, 2001, 2004, 2006, 2009, 2011, 2014, 2016, 2019 and 2021 in Northeast China, and the years 1984, 1986, 1989, 1991, 1994, 1996, 1999, 2001, 2004, 2006, 2009, 2011, 2014, 2016, 2019 and 2021 in South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia. Then, we utilized these regrowth time maps of secondary forests as masks to extract the LAI and FPAR maps for corresponding years, resulting in secondary forest LAI and FPAR maps for the preceding and subsequent years of the historical target years in each region. Finally, we generated the maps of regrowth rates for secondary forest LAI and FPAR for historical target years using Eq. (2) based on these secondary forest LAI and FPAR maps. This includes maps for the years 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020 in North America and Europe, the years 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020 in Northeast China, and the years 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020 in South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia.

where \({Re\_}{{Rate}}_{p}\) represents the regrowth rate for a structural parameter of the secondary forest; \({{Value}}_{{p\_sub}}\) represents the value of the parameter for the preceding year, and \({{Value}}_{{p\_pre}}\) represents the structural parameter value for the subsequent year; \(n\) represents the number of interval years that is considered as 2 in this study. If the calculated regrowth rate for a pixel is negative, it is assigned a value of zero. This is because the parameter may exhibit fluctuations in its values after reaching saturation of regrowth at certain locations for a certain year, which we considered as a state of non-growth. Before reaching the saturation of regrowth, the regrowth rate will vary in different target years. Figure 6, S8–S10 show the regrowth rates of secondary forest height, AGB, LAI, and FPAR in 2020 following deforestation, and Figure S11 shows a historical regrowth ratio following deforestation in a typical region of South America.

Regrowth rate of secondary forest height in 2020 following deforestation. (A) North America. Deforestation in this region occurred from 2001 to 2015, (B) Europe. Deforestation in this region occurred from 2001 to 2019, (C) Northeast China. Deforestation in this region occurred from 1986 to 2019, and (D–F) South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia. Deforestation in these regions occurred from 1982 to 2019.

Data Records

The dataset developed in this study is formatted in GeoTIFF at a spatial resolution of 30 meters, accessible for download via figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27134505)37. The user interface of the dataset can be accessed through the Earth Engine APP (https://woshigou123456789.users.earthengine.app/view/deforest-regrowth). The organization of the dataset is delineated in Fig. 7. To accommodate the diverse temporal sequences of data across different regions, we organized the regrowth dataset by geographical regions. Within each region, we categorized the regrowth land types into secondary forests (including naturally regenerated forests and tree plantations) and other regrowth types. In secondary forest areas, we mapped the regrowth ratio and rate for each parameter (Height, AGB, LAI, and FPAR) of the secondary forest across multiple years, with intervals of 5 years. For instance, in the case of Southeast Asia, the filenames and naming conventions for the bands are:

Filename:

Southeast Asia_Height_regrowth.tif: Height regrowth of secondary forests following deforestation in Southeast Asia.

Southeast Asia_AGB_regrowth.tif: AGB regrowth of secondary forests following deforestation in Southeast Asia.

Southeast Asia_LAI_regrowth.tif: LAI regrowth of secondary forests following deforestation in Southeast Asia.

Southeast Asia_FPAR_regrowth.tif: FPAR regrowth of secondary forests following deforestation in Southeast Asia.

Bands of a file such as the Southeast Asia_height_regrowth.tif are:

Regrowth_type_2020: Regrowth land type in 2020 following the deforestation between 1982 and 2019. The tree plantation, naturally regenerated forest and others are coded as 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Height_regrowth_ratio_year: Height regrowth ratio of secondary forests following deforestation for a target year.

Height_regrowth_rate_year: Height regrowth rate of secondary forests following deforestation for a target year.

The unit of the regrowth ratios for all structural parameters of secondary forests is “%”, and the unit of the regrowth rates for height, AGB, LAI, and FPAR of secondary forests is “m/year” with a scale of 0.1, “Mg/ (900 m2 year)” with a scale of 0.1, “/year” with a scale of 0.01, and “/year” with a scale of 0.0004, respectively.

Technical Validation

Given the absence of similar forest regrowth ratios and rates products comparable to our dataset, our validation efforts focused solely on confirming the accuracy of the estimated secondary forest height and AGB values, which underpin the calculations of the forest regrowth ratio and rate. The forest height map for the year 2000 in Potapov., et al.14 was utilized as a reference map to validate our secondary forest height map for the same year (Fig. 8). Notably, the secondary forest heights for the year 2000 in North America and Europe were not included in our estimation. To validate the estimated heights, we employed the regrowth time map of secondary forests for the year 2000 as a mask to extract the reference forest height map, yielding a reference secondary forest height map for the year 2000. Subsequently, we generated 50,000 random points for each region (excluding North America and Europe), and used only valid points within the secondary forest area for the year 2000 to extract samples from both our estimated and reference heights of secondary forests. The number of valid samples used for validating the estimated heights varied across regions due to differences in secondary forest areas (Fig. S13).

The height validation results demonstrate reasonable accuracy of the estimated secondary forest height, with R2 values ranging from 0.41 to 0.47 and RMSE within the range of 3.91 m to 4.87 m (Fig. 8). Notably, secondary forest height estimation in Southeast Asia exhibits superior performance, achieving an R2 of 0.44 and an RMSE of 3.91 m. Although the height estimation in Northeast China falls slightly below the reference height, the RMSE (4.87 m) is deemed acceptable relative to that (6.6 m) reported in Potapov, et al.12 for estimating forest height.

The forest AGB map for the year 2010 in Santoro and Cartus15 was utilized as the reference map to validate our secondary forest AGB map for the same year (Fig. 9). Similarly, we used the regrowth time map of secondary forests for the year 2010 as a mask to extract the reference forest AGB map, resulting in a reference secondary forest AGB map for the year 2010. Then, we aggregated the pixels of the estimated secondary forest AGB map from 30 m to 100 m resolution using the averaging method, and converted the unit from Mg/900 m2 to Mg/ha to match the resolution (100 m × 100 m) of the map in Santoro and Cartus15. Finally, we directly employed the random points from Fig. 3 and selected valid points of them within the secondary forest area for the year 2010 to extract samples from both our estimated and reference AGBs of secondary forests in 2010. The comparison results also indicate reasonable accuracy of the estimated secondary forest AGB, with R2 values ranging from 0.36 to 0.59 and RMSE within the range of 6.03 Mg/ha to 30.63 Mg/ha (Fig. 9). Notably, secondary forest AGB estimation in South America and Africa demonstrates superior performance, with R2 approaching 0.6.

Collectively, these validation outcomes underscore the good accuracy of our estimated secondary forest heights and AGBs across diverse regions, thus ensuring the reliability of the forest regrowth ratio and rate calculations.

Usage Notes

This study introduces the first dataset documenting forest regrowth in key deforestation regions globally, spanning nearly four decades at a 30 m resolution. Unlike previous research that predominantly focused on area recovery, our emphasis lies on the structural regrowth of forests. This offers more nuanced insights into global forest regrowth dynamics subsequent to deforestation events. Our dataset serves as a crucial resource for assessing forest ecology equilibrium and carbon dynamics following deforestation. Furthermore, the regional age-height models for secondary forest growth (Table 1) and the regrowth rate equations for both secondary forest height and AGB presented herein (Table 3) greatly enhance the analytical toolkit for investigating regional patterns of forest regrowth following disturbances.

Due to the current lack of a comprehensive global deforestation product, we utilized multiple data products to determine the extent of deforestation in globally key regions. This approach is scientifically justified, as all the deforestation and disturbance-related datasets we utilized are primarily generated by leveraging the multispectral and multitemporal attributes of the Landsat archive, and they also exhibit high identification accuracies1,2,18,20. Consistent use of the same input data, similar methodologies, and consistently high accuracy ensure that the resulting data products possess highly similar strengths and limitations across different regions. On the other hand, our regrowth dataset is developed based on the extent of forest recovery, which is derived from the identified deforestation extent. Consequently, the accuracy of the deforestation extent primarily affects the reliability of our regrowth dataset. However, this impact may not be significant, as the producer’s and user’s accuracies of the deforestation and disturbance-related datasets all exceed 85%.

For the extent of forest recovery, we have employed three datasets including the forest cover change in TMF2, FNF map27, and global map of planting years for plantations28, to assist in identifying the secondary forest areas. The errors or uncertainties in the spatial distribution of the identified secondary forests may secondarily affect the spatial accuracy of the forest regrowth maps. However, these datasets represent the most current and advanced techniques for forest identification available in recent years. It is challenging to avoid the errors in these datasets through simple efforts, especially since there are differences in the input data and algorithms they use for forest identification. Concerning this issue, we believe the accuracy validation results for each dataset could serve as a reference for indicating the potential spatial uncertainties of the forest regrowth maps.

In North America, we used the distribution of commodity-driven deforestation reported from Curtis, et al.17 as a mask to extract the 30 m resolution annual forest loss map from the GFC dataset over the same period, to determine the 30 m resolution deforestation areas. However, due to the lower resolution (10 km × 10 km) of the deforestation data in Curtis, et al.17, the resulting 30 m resolution deforestation areas exhibit a composite form, with blocky contours from the 10 km resolution data overlaid on 30 m resolution pixels (Fig. 2a). It is worth noting that some block-like gaps in the map do not represent missing deforestation areas, but rather areas classified by Curtis, et al.17 as other disturbance types. Given the high classification accuracy of the two data sources, conducting low-resolution analyses of forest regrowth following deforestation in North America using our dataset is unlikely to pose significant issues. We anticipate the availability of 30 m resolution deforestation or windthrow data products in North America, which will help address this situation more effectively. When such data become available, we will immediately update and replace the current forest regrowth maps in North America.

For the deforestation dataset we used in tropical regions, the Landsat archive, which underpins the dataset, has limited valid observations in areas such as Ecuador and Colombia in South America, as well as large portions of Africa2. This limitation may result in these regions appearing to have less post-deforestation recovery than is actually the case. Despite these constraints, the Landsat archive remains the only freely accessible, long-term satellite imagery resource that is suitable for analyzing land cover changes over extended periods at a fine spatial resolution. Therefore, until more comprehensive deforestation datasets become available, the Landsat archive provides the most reliable and effective data currently accessible for this purpose.

While some studies have developed regional age-height models for tree growth, we opted not to utilize them due to variations in tree height metrics34 or the temporal scope of tree growth assessments33. For each key deforestation region in this study, we employed dominant forest type as the representative secondary forest to calibrate the tree age-height model or employed the height-AGB allometric equation. We acknowledge that there may be a small portion of other forest types within the forest recovery areas. However, developing tree age-height models for each forest type in a specific region is challenging because the number of samples from secondary forests of subdominant types is significantly lower than that of dominant secondary forests, making it difficult to establish robust growth models. Therefore, we simplified this process by representing the secondary forest type in each key deforestation region using the dominant forest type.

It is important to acknowledge that the original resolution of the forest LAI and FPAR datasets does not match our 30 m resolution. The AVHRR LAI and PFAR datasets exhibited relatively high uncertainty during the resampling process due to the coarse resolution (Fig. S2). Should higher-resolution LAI and FPAR datasets become accessible in the future, we will incorporate them into our process. Nevertheless, this limitation does not impede the regional-level analysis of forest regrowth. Furthermore, although the forest regrowth ratio and rate following deforestation were not directly validated, the validation of estimated secondary forest height and AGB values across diverse regions lends credibility to the calculated results of the forest regrowth ratio and rate.

Code availability

The GEE code used to generate and access the dataset in this study is available at https://github.com/JinlongZang/DeforestRecovery.

References

Hansen, M. C. et al. High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change. Science 342, 850–853 (2013).

Vancutsem, C. et al. Long-term (1990–2019) monitoring of forest cover changes in the humid tropics. Sci Adv 7, eabe1603 (2021).

Ceccherini, G. et al. Abrupt increase in harvested forest area over Europe after 2015. Nature 583, 72−+ (2020).

Pilli, R., Grassi, G., Kurz, W. A., Viñas, R. A. & Guerrero, N. H. Modelling forest carbon stock changes as affected by harvest and natural disturbances. I. Comparison with countries’ estimates for forest management. Carbon Bal Manage 11 (2016).

Heinrich, V. H. A. et al. The carbon sink of secondary and degraded humid tropical forests. Nature 615, 436–442 (2023).

Poorter, L. et al. Multidimensional tropical forest recovery. Science 374, 1370–1376 (2021).

Cook-Patton, S. C. et al. Mapping carbon accumulation potential from global natural forest regrowth. Nature 585, 545–550 (2020).

Rozendaal, D. M. A. et al. Biodiversity recovery of Neotropical secondary forests. Sci Adv 5, eaau3114 (2019).

Decuyper, M. et al. Continuous monitoring of forest change dynamics with satellite time series. Remote Sens Environ 269, 112829 (2022).

Kim, D. H. et al. Global, Landsat-based forest-cover change from 1990 to 2000. Remote Sens Environ 155, 178–193 (2014).

Rendenieks, Z., Nita, M. D., Nikodemus, O. & Radeloff, V. C. Half a century of forest cover change along the Latvian-Russian border captured by object-based image analysis of Corona and Landsat TM/OLI data. Remote Sens Environ 249, 112010 (2020).

Potapov, P. et al. Mapping global forest canopy height through integration of GEDI and Landsat data. Remote Sens Environ 253, 112165 (2021).

Dubayah, R. et al. GEDI L2A Elevation and Height Metrics Data Global Footprint Level V002 [Data set]. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC https://doi.org/10.5067/GEDI/GEDI02_A.002 (2021).

Potapov, P. et al. The Global 2000–2020 Land Cover and Land Use Change Dataset Derived From the Landsat Archive: First Results. Frontiers in Remote Sensing 3, 856903 (2022).

Santoro, M. & Cartus, O. ESA Biomass Climate Change Initiative (Biomass_cci): Global datasets of forest above-ground biomass for the years 2010, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2020, v4. NERC EDS Centre for Environmental Data Analysis https://doi.org/10.5285/af60720c1e404a9e9d2c145d2b2ead4e (2023).

FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020: Main report. 184 (Rome, Italy, 2020).

Curtis, P. G., Slay, C. M., Harris, N. L., Tyukavina, A. & Hansen, M. C. Classifying drivers of global forest loss. Science 361, 1108–1111 (2018).

Tyukavina, A. et al. Global Trends of Forest Loss Due to Fire From 2001 to 2019. Frontiers in Remote Sensing 3, 825190 (2022).

Shikhov, A. N., Chernokulsky, A. V., Azhigov, I. O. & Semakina, A. V. A satellite-derived database for stand-replacing windthrow events in boreal forests of European Russia in 1986–2017. Earth Syst Sci Data 12, 3489–3513 (2020).

Zhu, Z. et al. Continuous monitoring of land disturbance based on Landsat time series. Remote Sens Environ 238, 11116 (2020).

Zhu, Z. & Woodcock, C. E. Continuous change detection and classification of land cover using all available Landsat data. Remote Sens Environ 144, 152–171 (2014).

Shang, R. et al. China’s current forest age structure will lead to weakened carbon sinks in the near future. The Innovation 4 (2023).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach Learn 45, 5–32 (2001).

van Wagtendonk, J. W., Root, R. R. & Key, C. H. Comparison of AVIRIS and Landsat ETM+ detection capabilities for burn severity. Remote Sens Environ 92, 397–408 (2004).

Rouse, J. W., Haas, R. H., Schell, J. A. & Deering, D. W. Monitoring vegetation systems in the great plains with ERTS. Third ERTS Symposium. NASA SP-351, NASA, Washington, DC. 1, 309–317 (1973).

Shang, R. et al. Near-real-time monitoring of land disturbance with harmonized Landsats 7-8 and Sentinel-2 data. Remote Sens Environ 278 (2022).

Shimada, M. et al. New global forest/non-forest maps from ALOS PALSAR data (2007–2010). Remote Sens Environ 155, 13–31 (2014).

Du, Z. et al. A global map of planting years of plantations. Sci Data 9, 141 (2022).

Kennedy, R. E., Yang, Z. G. & Cohen, W. B. Detecting trends in forest disturbance and recovery using yearly Landsat time series: 1. LandTrendr - Temporal segmentation algorithms. Remote Sens Environ 114, 2897–2910 (2010).

Danylo, O. et al. A map of the extent and year of detection of oil palm plantations in Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. Sci Data 8, 96 (2021).

Ma, H. & Liang, S. Development of the GLASS 250-m leaf area index product (version 6) from MODIS data using the bidirectional LSTM deep learning model. Remote Sens Environ 273, 112985 (2022).

Ma, H. et al. Global land surface 250 m 8 d fraction of absorbed photosynthetically active radiation (FAPAR) product from 2000 to 2021. Earth Syst Sci Data 14, 5333–5347 (2022).

Zang, J., Ni, W. & Zhang, Y. Spatially-explicit mapping annual oil palm heights in peninsular Malaysia combining ICESat-2 and stand age data. Remote Sens Environ 295, 113693 (2023).

Milenković, M. et al. Assessing amazon rainforest regrowth with GEDI and ICESat-2 data. Science of Remote Sensing, 100051 (2022).

Tan, K. P., Kanniah, K. D. & Cracknell, A. P. Use of UK-DMC 2 and ALOS PALSAR for studying the age of oil palm trees in southern peninsular Malaysia. Int J Remote Sens 34, 7424–7446 (2013).

Xu, L. et al. Changes in global terrestrial live biomass over the 21st century. Sci Adv 7, eabe9829 (2021).

Jinlong, Z., Feng, Q., Yongguang, Z., Rong, S. & Yunjian, L. A dataset of forest regrowth in globally key deforestation regions. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27134505 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant numbers: 2019YFA0606603 and 2019YFA0606601) and the Open Fund of State Key Laboratory of Remote Sensing Science (grant number: OFSLRSS202223).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was designed by Yongguang Zhang and carried out by Jinlong Zang with help from Feng Qiu, Rong Shang and Junjian Liang. Jinlong Zang wrote the first version of the manuscript, and all authors contributed to improving the text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zang, J., Qiu, F., Zhang, Y. et al. A dataset of forest regrowth in globally key deforestation regions. Sci Data 12, 154 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04481-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04481-3