Abstract

Leptopilina wasps are crucial for biological pest control, particularly against the globally emerging pest Drosophila suzukii. Despite their ecological significance, the genomic basis of host selection and parasitism in this genus remains underexplored. In this study, we assembled a high-quality, chromosome-level genome of Leptopilina myrica, a species collected in Taizhou, Zhejiang Province, China. We employed a combination of PacBio long-read sequencing, Illumina short-read sequencing, and Hi-C technology to produce a genome assembly of approximately 462.30 Mb, with a scaffold N50 of 47.32 Mb and a contig N50 of 4.07 Mb. By comparing the protein-coding genes of L. myrica with those of other Hymenoptera species, we gained insights into the evolutionary history of parasitoid wasps. This high-quality genome will provide a foundation for future research on the genetic and functional traits of parasitoid wasps, shedding light on the evolutionary dynamics of host-parasite interactions. The genome of L. myrica provides a valuable resource for future studies on host-parasite interactions and the genetic basis of parasitoid wasp biology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Parasitic Hymenoptera represent the most species-rich group of parasitic organisms. They parasitize a broad range of insect groups and other arthropods, including caterpillars, leafhoppers, aphids, flies, spiders, and ticks—many of which are agricultural pests1. As a result, parasitic Hymenoptera play a vital role in sustainable and environmentally friendly agricultural pest management. However, our understanding of the genetic mechanisms behind parasitism in this group, particularly in terms of host specificity and immune evasion, remains limited due to the scarcity of high-quality genomic resources. Access to genomic data holds significant potential for identifying key parasitic effectors and advancing biopesticide development for large-scale use in agriculture.

The genus Leptopilina includes a few parasitoid wasps that have been studied in detail, particularly in the context of host-parasite interactions2,3,4,5. They have recently garnered attention due to their ability to parasitize and control the growing threat of the invasive pest Drosophila suzukii6,7. These studies have provided important insights, highlighting intriguing evolutionary dynamics and the practical implications for parasitoid wasps, while also emphasizing the need for further genomic research. Despite this progress, much of the genetic basis underlying parasitism in this genus remains unexplored.

In this study, we captured a Leptopilina species in Taizhou, Zhejiang Province, China, using fruit traps in a Myrica rubra plantation. We assembled a chromosome-level genome of this species, referred to as Leptopilina myrica, by utilizing a combination of PacBio long-read sequencing, Illumina short-read sequencing, and Hi-C chromosome conformation capture technologies. We then compared the protein-coding genes of L. myrica with those of other Hymenoptera species to gain insights into the evolutionary history of parasitoid wasps. The high-quality genome assembly obtained in this study will provide a valuable resource for future investigations into the genetic mechanisms underlying parasitoid traits.

Methods

Sample collection and preparation

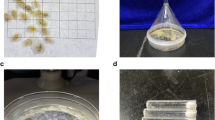

We collected L. myrica samples using fruit traps in Taizhou, Zhejiang Province, China. The samples were maintained in the laboratory using Drosophila melanogaster (w1118) as the regular host, under controlled conditions: 25 °C temperature, ~50% relative humidity, and a 16:8 light-dark cycle.

Genomic DNA Sequencing and de novo Assembly

Genomic DNA was extracted from a pool of approximately 1,000 male specimens for PacBio sequencing, using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen). A 20-Kb genomic library was constructed and sequenced by Berry Genomics Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China) on a PacBio Sequel platform, following standard protocols. This sequencing yielded 112.14 Gb of long-read data, with an N50 read length of ~25,337 bp and an average read length of ~22,506 bp.

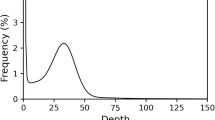

For genome error correction, we used the Illumina platform to generate short reads. The Illumina sequencing produced 21.57 Gb of raw data, which was filtered to remove adapters and low-quality reads using fastp v0.20.08, resulting in 20.06 Gb of clean reads (Table 1).

To assemble contigs, Nextdenovo v2.4.0469 was utilized with the following parameters: “read_type = clr read_cutoff = 2k genome_size = 900 m seed_depth = 60 nextgraph_options = -a 1 -A”. The contigs were then corrected and polished using Illumina paired-end reads via Nextpolish v1.3.14710, with parameters: “task = best rerun = 3 sgs_options = -max_depth 100 -bwa lgs_options = -min_read_len 1k -max_depth 100 lgs_minimap2_options = -x map-pb”. Finally, the polished contigs underwent two rounds of redundancy removal using purge_dups v1.2.34811 with default parameters. The genome size of the first assembly was 462.09 Mb, with a contig N50 of 4.07 Mb across 274 contigs (Table 2).

Chromosome staining

For karyological analysis, we prepared chromosomes from L. myrica following a modified version of the protocol outlined by Imai et al.12. Cerebral ganglia were dissected from early pupae of male wasps in Ringer’s saline solution and rinsed in Ringer’s buffer for 3–5 minutes. Ganglia were then incubated in a 0.005% colchicine-hypotonic solution (diluted in 1% sodium citrate) for 30 minutes. After incubation, the ganglia were transferred onto clean slides, fixed in Fixative Solution A (ethanol, glacial acetic acid, and distilled water in a 3:3:4 ratio by volume), and gently disaggregated using forceps for even chromosome distribution. The samples were then fixed in Fixative Solution B (ethanol and glacial acetic acid in a 1:1 ratio by volume) and mounted in ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Invitrogen). Fluorescence images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 800 confocal microscope (Fig. 1a,b).

Hi-C sequencing and scaffolding

Hi-C libraries for L. myrica were prepared from a pool of 20 newly emerged males following the protocol outlined by Lieberman-Aiden et al. (2009). The samples were initially fixed with 2% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature, and glycine was added to a final concentration of 100 mM to stop the cross-linking reaction. Cross-linked DNA was extracted and digested overnight with HindIII (NEB). During the sticky-end repair process, Biotin-14-dCTP17 was incorporated. The interacting DNA fragments were then ligated using T4 DNA ligase to form chimeric junctions. Hi-C libraries were subsequently sequenced by GrandOmics Co. Ltd (Wuhan, China) on an Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform, generating 56.04 Gb of paired-end reads, providing approximately 121x genome coverage (Table 1).

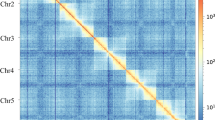

The assembled contigs were scaffolded using Hi-C contact information obtained from the Hi-C sequencing reads. Juicer v1.5.713 was employed to process the contact signals, which were then provided to 3d-dna v19071614 for chromosome grouping, using the parameters “--q 1 --editor-repeat-coverage 2.” The final chromosome interaction matrix was visualized as a heatmap, showing diagonal patches of strong linkage based on the interplay between valid mapped reads and bins using the Juicebox15 (Fig. 1c).

Finally, we obtained the high-quality chromosome-level genome of L. myrica, with the genome size of 462.30 Mb, with a scaffold N50 of 47.32 Mb and GC content of 27.27%. (Table 2).

RNA sequencing and analysis

Critical developmental stages were sampled for high-coverage RNA sequencing to capture a comprehensive transcriptome profile (Table 3). A total of 11 developmental stages of L. myrica were included: Egg, L1 (days 1–3 larvae; early larval stage), L2 (days 4–6 larvae; early to middle larval stage), L3 (days 7–9 larvae; middle to late larval stage), P1 (days 1–3 pupae; early pupal stage), P2 (days 4–7 pupae; early to middle pupal stage), P3 (days 8–10 pupae; middle to late pupal stage), adult females (AF), and adult males (AM). The VGs of 3-day-old AF wasps were dissected in Ringer’s saline solution on an ice plate under a stereoscope (Nikon). Total RNA was independently extracted from each sample using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) and stored at −80 °C until further use.

Construction of cDNA libraries and paired-end RNA sequencing (Illumina) was performed by Berry Genomics Co. Ltd. Transcriptome sequencing data statistics are provided in Table 3. Full-length transcripts were generated using the PacBio sequencing system (Pacific Biosciences), yielding 49.25 Gb of transcriptome sequencing data from libraries with insert sizes of 1–10 kb for the mRNA pool across all stages. Raw reads were processed using IsoSeq v3.2.216 and mapped to the reference genome using Minimap v2.1717 with the parameters “-ax splice --uf --secondary = no --C5”.

Repeat elements prediction

Repeat elements were annotated using the RepeatMasker pipeline. A species-specific repeat library was first generated using RepeatModeler v2.0.2 (www.repeatmasker.org), and RepeatMasker v4.1.1 was employed to mask repetitive content across the genome using both the species-specific library and Dfam v3.2. A total of 242,390,138 bp repetitive sequences were obtained, accounting for 52.43% of genome size (Fig. 2, Table 2). This proportion is consistent with that observed in other related species within the same superfamily. For example, Leptopilina boulardi has a repetitive content of 54.40%, and Belonocnema treatae has 56.10% (Table 4).

Genome annotation

Protein-coding genes were predicted based on the repeat-masked genome using multiple approaches: (1) BRAKER v2.1.518,19,20,21,22,23,24 was used to generate two gene sets, one based on transcriptome-based hints and the other on related protein-based hints; (2) Maker v2.31.1025 generated an integrated gene set by calling SNAP v2006-07-2826 and Augustus v3.3.227, incorporating evidence from related proteins and full-length transcripts; (3) StringTie v2.022 combined Illumina transcriptome data to generate a merged transcript set using default parameters; (4) TOFU’s28 Python module “collapse_isoforms_by_sam” processed long-read transcriptome data to produce a full-length transcript set, using parameters “--dun-merge-5-shorter -c 0.9 -i 0.9”. These independent gene sets were compared pairwise at both transcript and exon levels. Genes with consistent support from multiple sets were prioritized, while those supported by only a single set were excluded. Predicted genes were annotated based on BLASTP searches against the NR database and domain searches using InterProScan v5.38-76.029. Gene expression across developmental stages or tissues was quantified as TPM using salmon v0.12.030, with the parameters “quant -l A”. The integrated unified dataset led to the prediction of 13,832 protein coding genes distributed across the genome and a mean gene length was found to be 1,589.8 bp. (Table 2).

Phylogenetic analysis

OrthoFinder v2.5.131 was used to analyze orthologous and paralogous genes across 11 Hymenopteran genomes with parameter “-M msa”. These genomes are of high completeness and represent major clades within the order Hymenoptera, including Apoidea (Apis mellifera, Bombus consobrinus), Tenthredinoidea (Athalia rosae), Chalcidoidea (Nasonia vitripennis, Pteromalus puparum, Trichomalopsis sarcophagae), Ichneumonoidea (Diachasma alloeum, Microplitis demolitor), and Cynipoidea (Belonocnema treatae, Leptopilina boulardi, and Leptopilina myrica), as detailed in Table 4.

Single-copy orthologous sequences from these species were aligned using MAFFT v7.50532. Subsequently, a species tree was constructed based on orthologs using STAG v1.033. Calibration points for divergence within Hymenoptera (221–283 million years ago, mya), Apis mellifera + Athalia rosae (224- 304 million years ago, mya) and Belonocnema treatae + Pteromalus puparum (108–242 million years ago, mya) were obtained from TimeTree (timetree.org).

Gene family contraction and expansion were analyzed using CAFE v5.134, incorporating results from OrthoFinder, the phylogenetic tree, and divergence time estimates. The phylogenetic tree was visualized and enhanced using iTOL (https://itol.embl.de/#) (Fig. 3).

Phylogenetic tree. The maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree based on 2749 concatenated single-copy orthologous genes from 11 Hymenopterans. The bootstrap value of all nodes is supported at 100/100, and gene counts different types of orthologous groups. The expansion, contraction of orthologous groups (OGs) are shown on the nodes and tips. “1:1:1” indicates universal single-copy genes present in all species; “N: N: N” indicates multicopy genes, although the absence in a single genome is tolerated; “Leptopilina” means common unique genes in species from Leptopilina. “Species-specific” represents species-specific genes in the genome; “Unassigned” indicates genes which cannot be assigned into any gene families (orthogroups); “Others” means the remaining genes.

Data Records

PacBio, Illumina and Hi-C sequencing data have been deposited to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive with accession numbers SRR3132050635, SRR3132050536 and SRR3132050437 respectively. Additionally, RNA-Seq data are available and active in the NCBI database with accession numbers SRR3097868638, SRR3097868739, SRR3097868840, SRR3097868941, SRR3097869042, SRR3097869143, SRR3097869244, SRR3097869345, SRR3097869446 and SRR3097869547. The assembled genome can be found on NCBI’s GenBank through accession number GCA_032872475.148. The genome annotations were openly available from figshare49.

Technical Validation

We evaluated the quality of the L. myrica genome assembly by calculating mapping rates and assessing completeness. Using BWA v0.7.1750, we aligned PacBio and Illumina reads to the final assembly, achieving mapping rates of 99.35%, and 99.37%, respectively. Genome completeness was assessed with the BUSCO pipeline v5.2.151, using the insecta_odb10 database as a reference. The BUSCO analysis showed 98.1% completeness for the predicted protein-coding gene sequences, including 97.4% single-copy, 0.7% duplicated, 0.3% fragmented, and 1.6% missing BUSCOs.

Code availability

No custom code was developed for this study. All data processing commands and pipelines were executed following the manuals and protocols provided by the relevant bioinformatics software. Specific software tools and methods used are detailed in the Methods section.

References

Pennacchio, F. & Strand, M. R. Evolution of developmental strategies in parasitic Hymenoptera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 51, 233–258 (2005).

Quicray, M. et al. The Drosophila-parasitizing wasp Leptopilina heterotoma: A comprehensive model system in ecology and evolution. Ecol. Evol. 13, e9625 (2023).

Huang, J. et al. Two novel venom proteins underlie divergent parasitic strategies between a generalist and a specialist parasite. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–16 (2021).

Chen, J. et al. Neofunctionalization of an ancient domain allows parasites to avoid intraspecific competition by manipulating host behaviour. Nat. Commun. 12, 5489 (2021).

Poirié, M., Colinet, D. & Gatti, J. L. Insights into function and evolution of parasitoid wasp venoms. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 6, 52–60 (2014).

Girod, P. et al. The parasitoid complex of D. suzukii and other fruit feeding Drosophila species in Asia. Sci. Rep. 8 (2018).

Giorgini, M. et al. Exploration for native parasitoids of Drosophila suzukii in China reveals a diversity of parasitoid species and narrow host range of the dominant parasitoid. J. Pest Sci. (2004). 92 (2019).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. Fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. in Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Hu, J. et al. NextDenovo: an efficient error correction and accurate assembly tool for noisy long reads. Genome Biol 25, 107 (2024).

Hu, J., Fan, J., Sun, Z. & Liu, S. NextPolish: a fast and efficient genome polishing tool for long-read assembly. Bioinformatics 36, 2253–2255 (2020).

Guan, D. et al. Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 36, 2896–2898 (2020).

Hirotami, T. I., Robert, W. T., Michael, W. J. C. & Ross, H. C. Modes of spontaneous chromosomal mutation and karyotype evolution in ants with reference to the minimum interaction hypothesis. japanese J. Genet. 63, 159–185 (1988).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer Provides a One-Click System for Analyzing Loop-Resolution Hi-C Experiments. Cell Syst. 3, 95–98 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95 (2017).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox Provides a Visualization System for Hi-C Contact Maps with Unlimited Zoom. Cell Syst. 3, 99–101 (2016).

Guizard, S. et al. nf-core/isoseq: simple gene and isoform annotation with PacBio Iso-Seq long-read sequencing. Bioinformatics 39, btad150 (2023).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Stanke, M., Diekhans, M., Baertsch, R. & Haussler, D. Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding. Bioinformatics 24, 637–644 (2008).

Stanke, M., Schöffmann, O., Morgenstern, B. & Waack, S. Gene prediction in eukaryotes with a generalized hidden Markov model that uses hints from external sources. BMC Bioinformatics 7, 62 (2006).

Gabriel, L., Hoff, K. J., Brůna, T., Borodovsky, M. & Stanke, M. TSEBRA: transcript selector for BRAKER. BMC Bioinformatics 22, 566 (2021).

Bruna, T., Lomsadze, A. & Borodovsky, M. GeneMark-ETP: Automatic Gene Finding in Eukaryotic Genomes in Consistency with Extrinsic Data. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.13.524024 (2023).

Kovaka, S. et al. Transcriptome assembly from long-read RNA-seq alignments with StringTie2. Genome Biol. 20, 278 (2019).

Pertea, G. & Pertea, M. GFF Utilities: GffRead and GffCompare. F1000Research 9, ISCB Comm J-304 (2020).

Quinlan, A. R. BEDTools: The Swiss-Army tool for genome feature analysis. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma. 2014, 11.12.1–11.12.34 (2014).

Cantarel, B. L. et al. MAKER: An easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome Res. 18, 188–196 (2008).

Korf, I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 5, 59 (2004).

Stanke, M. et al. AUGUSTUS: A b initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W435–439 (2006).

Gordon, S. P. et al. Widespread polycistronic transcripts in fungi revealed by single-molecule mRNA sequencing. PLoS One 10, e0132628 (2015).

Zdobnov, E. M. & Apweiler, R. InterProScan - An integration platform for the signature-recognition methods in InterPro. Bioinformatics 17, 847–848 (2001).

Patro, R., Duggal, G., Love, M. I., Irizarry, R. A. & Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 14, 417–419 (2017).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: Phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 20, 238 (2019).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Emms, D. M., Kelly & Affiliations. STAG: Species Tree Inference from All Genes. bioRxiv (2018).

Mendes, F. K., Vanderpool, D., Fulton, B. & Hahn, M. W. CAFE 5 models variation in evolutionary rates among gene families. Bioinformatics 36 (2020).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31320506 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31320505 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR31320504 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR30978686 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR30978687 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR30978688 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR30978689 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR30978690 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR30978691 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR30978692 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR30978693 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR30978694 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR30978695 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_032872475.1 (2024).

Dong, Z. Chromosome-level genome sequencing and assembly of the parasitoid wasp Leptopilina myrica. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26819455.v2 (2025).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: Assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (grant number 2023YFD1400600) and the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number LZ23C140003) to J.H., and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 32202375) to J.C.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C. and J.H. conceived and led the research, J.Z., Y.G., Q.Z., L.P., T.F., W.S. and Y.S. were involved in sample collection and preparation. Z.D. and Z.X. contributed to genome assembly, gene prediction and annotation, data visualization and other bioinformatics analysis. Z.D., Z.X. and J.C. wrote the manuscript and all authors read, revised and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, Z., Xu, Z., Zhang, J. et al. Chromosome-level genome sequencing and assembly of the parasitoid wasp Leptopilina myrica. Sci Data 12, 235 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04577-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04577-w