Abstract

Amid growing global food security concerns and frequent armed conflicts, real-time monitoring of abandoned cropland is essential for strategic planning and crisis management. This study develops a method to map abandoned cropland accurately, crucial for maintaining the food supply chain and ecological balance. Utilizing Sentinel-1/2 satellite data, we employed multi-feature stacking and machine learning to create the ARCC10-IM (Abandoned and Reclaimed Cropland Classification at 10-meter resolution in Inner Mongolia) dataset, which tracks annual cropland activity. A novel temporal segmentation algorithm was developed to extract cropland abandonment and reclamation patterns annually, using sliding time windows over several years. This research differentiates cropland states—active cultivation, unstable fallowing, continuous abandonment, and reclamation—providing continuous, regional-scale maps with 10-meter resolution. ARCC10-IM is crucial for land planning, environmental monitoring, and agricultural management in arid areas like Inner Mongolia, enhancing decision-making and technology in land use tracking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Accurate cropland information is vital for agricultural planning and food production, especially in countries like China, where food security remains a major concern1. Since the late 20th century, China has seen a significant expansion of cropland, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions. This expansion into less suitable land has contributed to both land degradation and abandonment, with many areas now idle or degraded2. In regions where cropland resources are limited, such as Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, and Gansu, the idling and abandonment of cropland pose challenges not only to food security but also to land management and ecological sustainability3.

As of 2015, abandoned cropland in China accounted for approximately 392,156 square kilometers, or 13.03% of the total cropland area4. This phenomenon is concentrated in central-western and southwestern China, where harsh environmental conditions and unsustainable agricultural practices have driven the abandonment. Research estimates suggest that this loss of productive cropland could result in an annual grain deficit of 7.94 million tons. —enough to feed nearly 20 million people4. Moreover, the retirement of croplands is now seen as an option to meet environmental targets, helping revert degraded lands to natural ecosystems. Thus, the need for continuous monitoring is crucial not only for food security but also for environmental sustainability.

Cropland abandonment in Inner Mongolia is driven by environmental degradation, drought, and socioeconomic factors. Grassland reclamation has worsened soil conditions, making semi-arid lands more vulnerable. Droughts and water shortages further limit farming on marginal lands, while labor migration and declining agricultural profitability contribute to abandonment. Studies report that 13–20% of cropland in the region is abandoned, with up to 40% left uncultivated during drought years in specific areas like the Yinshan region4,5,6,7,8.

Remote sensing technology, with its extensive coverage, high efficiency, and dynamic monitoring capabilities, has become an essential tool for studying and managing fallow and abandoned agricultural lands9,10. Vegetation indices derived from satellite imagery provide a reliable representation of vegetation cover and growth conditions, offering valuable data for identifying and monitoring abandoned croplands11. However, there is still a lack of continuous high-resolution, high-frequency monitoring of abandoned and reclaimed cropland, as well as standardized monitoring methods. While the issue of cropland abandonment in southwestern China has garnered significant attention12,13,14, the problem in northern China’s farming-pastoral ecotone, particularly Inner Mongolia, remains underexplored. National-scale studies often rely on MODIS data, which offers limited spatial resolution, or use multi-year land use data overlays that do not capture the full dynamics of cropland abandonment, fallowing, and reclamation5.

Existing research faces several challenges: (1) The availability of high-resolution data (typically 1 to 10 meters) alone does not guarantee accurate results, particularly for complex and fragmented landscapes like those found in China. Abandoned lands in China are often scattered and fragmented15,16,17,18, especially in regions where per capita cropland is already below the global average. Using high-resolution imagery without considering the specific characteristics of abandoned cropland and crop phenology (such as the seasonal decline in NDVI during the harvest period) may lead to significant overestimations or underestimations of abandoned land. Thus, mid-resolution (mainly 30 meters) and low-resolution (greater than 30 meters) remote sensing images are often inadequate for mapping such dynamic and unstable lands. (2) Errors in baseline cropland data are particularly challenging for abandoned cropland mapping, as inaccuracies in the original land use data can propagate through subsequent analyses. This is especially true in regions like Inner Mongolia, where dry and semi-arid climates cause long-term land use instability. During critical growing phases, drought stress can lead to confusion between active croplands and naturally vegetated or fallow fields in surface reflectance data. Such uncertainties necessitate careful consideration of crop cycles and more refined methodologies, including incorporating key phenological stages (e.g., NDVI decline during the harvest period), to ensure that abandoned cropland is correctly identified.

Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data, with their high spatial resolution and frequent revisit times, are thus invaluable for monitoring cropland abandonment and reclamation. These satellite systems can not only capture changes accurately and in real time but also provide critical insights into small-scale farming activities and intra-field variations19,20. This is particularly important in regions like Inner Mongolia, where over half of the cropland is rainfed, making these areas particularly vulnerable to drought and water shortages, conditions that can result in lower crop productivity compared to irrigated lands21,22. This reliance on rainfall makes rainfed croplands critically important for understanding the region’s agricultural challenges and for ensuring both food security and ecological sustainability in China. Scientific monitoring and management of cropland use, particularly for rainfed lands, are essential for addressing these local land issues.

While some abandoned croplands may benefit from reversion to natural landscapes to achieve environmental goals, the scientific monitoring and management of cropland use in regions like Inner Mongolia remain key to balancing food security and ecological sustainability. In areas suitable for cultivation, improving land quality is essential, whereas, in less suitable areas, converting cropland to forest or grassland may be a more sustainable solution. Utilizing high-resolution and continuous observational data to monitor cropland dynamics in Inner Mongolia is not only necessary but also crucial for better understanding and managing this issue Fig. 1.

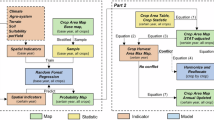

To address current challenges in monitoring cropland activity, we developed a standardized method for mapping and extracting abandoned and reclaimed cropland, aimed at generating a high-quality dataset for diverse users. The dataset production process includes the following key steps, as introduced in Fig. 1:

-

(1)

Cropland Base Map: We utilized and optimized the ESA WorldCover cropland base map to obtain a high-quality, 10-m resolution cropland base image for Inner Mongolia, serving as the foundation for dynamic monitoring.

-

(2)

NDVI Analysis: We analyzed NDVI threshold differences between major crops and inactive croplands during key growing seasons using Sentinel-2 data to generate a sample of active and inactive croplands.

-

(3)

Sample Optimization: By incorporating the rate of NDVI decline during the harvest period, we refined the sample set to ensure high-quality classification results.

-

(4)

Classification: Using the Random Forest classifier and feature stacking in Google Earth Engine (GEE) with Sentinel-1/2 data, we classified cropland activity for each year from 2016 to 2023.

-

(5)

Temporal Segmentation: A temporal segmentation algorithm was adapted to identify abandoned and reclaimed croplands, building on existing multi-year activity tracking methods. By integrating Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data and incorporating NDVI decline rates during key phenological stages, this method provides a more precise understanding of the spatiotemporal evolution of cropland activity.

Methods

Study area

The Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region is located along the northern border of the People’s Republic of China, adjoining Mongolia to the north. It spans from 97°12′ E to 126°04′ E and from 37°24′ N to 53°23′ N, covering an area of approximately 1.18 million square kilometers, which accounts for about 12% of China’s total land area. Inner Mongolia features diverse terrain, including plateaus, mountains, hills, and plains. Its maximum east-west extent is about 2400 kilometers, crossing three climatic zones—cold temperate, mid-temperate, and warm temperate—and it includes four moisture regions: humid, semi-humid, semi-arid, and arid (as shown in Fig. 2).

Inner Mongolia can be divided into seven agricultural natural regions: Cold Temperate Humid Zone, Mid-Temperate Humid Zone, Mid-Temperate Sub-Humid Zone, Mid-Temperate Semi-Arid Zone, Warm Temperate Sub-Humid Zone, Mid-Temperate Arid Zone, and Warm Temperate Arid Zone (https://www.resdc.cn/data.aspx?DATAID=273). Based on the area and distribution of cropland, these seven agricultural natural areas of Inner Mongolia can be consolidated into three main regions: the Mid-Temperate Sub-Humid Zone, Mid-Temperate Semi-Arid Zone, and Mid-Temperate Arid Zone, as shown in Fig. 2 and Table S1. Identifying the primary agricultural natural divisions is crucial for mapping abandoned croplands in Inner Mongolia.

According to the Third National Land Survey of China, Inner Mongolia has over 11.33 million hectares of cropland and produced about 39.58 million tons of grain in 2023, reinforcing its role as a major agricultural hub for China and East Asia. The region’s diverse geography and climate create distinct east-west variations. The eastern area, influenced by a monsoon climate, is the primary grain-producing region with high yields. The central region, situated in a temperate semi-arid zone, specializes in growing cold-resistant, low-water crops and is crucial for forage production. The arid western region relies on irrigation and faces severe agricultural challenges due to the unregulated development of once-desertified grasslands, resulting in substantial non-arable land and low-yielding rainfed farms.

Cropland mask

Cui et al.1 conducted a comparative evaluation of several cropland mapping datasets widely used in China, including three 10-meter resolution products (Google Dynamic World, ESRI Land Cover, ESA WorldCover) and three 30-meter resolution products (GLC_FCS30, GlobeLand 30, CLCD). Their results showed that the ESA WorldCover dataset, which integrates Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data, outperformed the other 10-meter datasets, achieving an accuracy of 92.3% in cropland mapping. Despite being a global product, ESA WorldCover performed exceptionally well in China, particularly in non-mountainous and climatically stable regions.

For this study, we assumed that from 2016 to 2023, there were no significant large-scale expansions or contractions in cropland. Based on this assumption, we used the cropland pixels from ESA WorldCover (2021) to establish an initial baseline map for Inner Mongolia. This data, freely available via the ESA WorldCover viewer and Google Earth Engine (GEE), classifies cropland under category 40, with a global accuracy of 81.1%, ranking third overall, just behind water bodies and impervious surfaces23.

Accurate cropland basemaps are crucial for monitoring abandoned and reclaimed croplands, which often occur in low-yield rainfed fields or marginalized croplands24,25,26. In this study, we define cropland abandonment as land that has not been cultivated for more than two consecutive years, while fallow land is defined as cropland left uncultivated for up to two years, typically for crop rotation or soil recovery purposes. However, errors can arise in global datasets like ESA WorldCover, particularly in areas like the farming-pastoral ecotones of Inner Mongolia, where the boundaries between croplands and managed grasslands are often blurred. These errors can lead to cropland being confused with grasslands, especially when activities like grazing or mowing are overlooked.

To mitigate these errors, we classified active and inactive croplands on top of the ESA WorldCover cropland basemap, which helps minimize misclassification. Additionally, to further improve the quality of our cropland base map, we manually corrected any misclassifications by comparing the data with high-resolution Maxar imagery accessed via Google Earth. We selected the most recent imagery, and although the imagery may come from different seasons, the boundaries and textures of croplands remain distinguishable even outside of the growing season due to the minimal changes in cropland use in recent years. Specifically, to improve the accuracy of our cropland identification, we adopted the visual inspection method, as suggested by Olofsson et al.27 to manually remove obvious misclassifications from the original cropland basemap and enhance overall classification accuracy. They recommend employing such methods where appropriate to correct errors and refine classification results as part of good practices for land cover accuracy assessment.

After revisions, we randomly selected 4,000 verification points on the high-resolution satellite data from Google Earth within the Inner Mongolia to check if they all fell on the corrected cropland basemap. This method achieved an impressive total accuracy of 96.38% in cropland mapping in Inner Mongolia, demonstrating the effectiveness of optimizing the cropland basemap.

Remote sensing images and DEM data

Sentinel-1 images

The Sentinel-1 archive provides data from a dual-polarized C-band SAR (Synthetic Aperture Radar) instrument. The dataset includes Sentinel-1 Ground Range Detected (GRD) scenes, processed using the Sentinel-1 Toolbox to produce calibrated and orthorectified products on the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform. In this study, Sentinel-1A data from 2017 to 2023 were used to create annual maps of cropland activity. This data has a spatial resolution of 10 m and a temporal resolution of 12 days. Previous studies have indicated that Vertical-Vertical (VV) polarization data is more sensitive to soil moisture compared to Vertical-Horizontal (VH) polarization data28. VH data, on the other hand, is more sensitive to volume scattering, largely dependent on the geometric arrangement and characteristics of the associated vegetation29. Given the variations in vegetation density and soil conditions in uncultivated croplands, this study utilizes both VV and VH polarization to develop a mapping method for uncultivated croplands.

Sentinel-2 Data

We acquired top-of-atmosphere corrected Sentinel-2 (MSI Level-1C) data from 2016 to 2023, including data from both Sentinel-2A and Sentinel-2B. The dual-satellite configuration enables repeat monitoring of the Earth’s surface every five days, providing a continuous set of high-quality images for creating annual cropland activity maps. In this study, we excluded the Aerosol band due to its lower resolution (60 meters) and unsuitability for atmospheric monitoring, as well as the four red-edge bands. During data preprocessing, we applied a cloud cover filter (set to <20%) to filter out cloudy images from the Sentinel-2 archive. Additionally, the QA60 band was utilized to remove cloud pixels and obtain clear observation pixels for the study area. Further data details are provided in Table 1.

DEM images

Altitude is a key factor influencing cropland abandonment30. Therefore, we used the global 30-meter resolution digital elevation data provided by NASA JPL-SRTM to extract terrain elevation and slope31, which helps in the annual classification of active and inactive cropland.

Sample collection

Ground reference sample collection

In 2022 and 2023, we systematically collected ground sample points of various crops and inactive croplands (defined as lands that were previously cultivated but left uncultivated in the year of collecting ground samples. These lands may be temporarily fallow or permanently abandoned, but they had not been subject to any agricultural activities) in Inner Mongolia. This sample collection was divided into two steps: First, we combined ground field surveys and drone aerial photography to collect sample points of various main crops and inactive cropland of the year in Inner Mongolia’s three main agricultural natural areas, ensuring the representativeness of the samples. Ground surveys provided direct observational data of the crops, while drone aerial photography expanded the sample collection range, enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of data collection. Through these methods, in 2022 we collected a total of 2793 crop sample points, covering major single-season crops such as corn, sunflower, spring wheat, oats, canola, beet, potato, soybean, and paddy, spanning from the western to the eastern parts of Inner Mongolia. These samples were used to derive NDVI curves based on real ground crop points, extracting key growth stages for automated classification and optimization procedures.

Additionally, we collected 251 ground sample points of inactive cropland, with detailed distribution shown in Fig. 2 and specific quantities provided in Table 2. Due to the relatively smaller number of samples in 2023, mainly concentrated in the arid zone of Inner Mongolia, the 2023 samples were primarily used to verify the accuracy of the classification results, with specific sample point numbers also listed in Table 2.

Derivational sample generation

Building on the collection of ground field sample points, this study employed a method that analyzes the differences in NDVI mean values between active and inactive croplands during key growth periods. By examining changes in the slope during the harvest period, we excluded disruptive sample points, resulting in an optimized set of samples. Throughout the research process, we adopted the method of expert consultation, successfully collecting phenology data for various crops within the three main agricultural natural regions of Inner Mongolia and organizing it into a table (details in Table S2). This process involved in-depth discussions with local agricultural experts and experienced farmers who possess unique insights and extensive observational records of the growth cycles and key phenological stages of crops in these regions. Through this approach, we obtained a detailed phenological calendar that records the timing of various stages for different crops—from planting to growth, flowering, maturity, and harvest—providing foundational data for further analysis. The process of sample generation, classification, and optimization then proceeded as follows:

-

(1)

On the cropland basemap of Inner Mongolia, we randomly generated 50,000 sample points using the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform. These points were uniformly distributed across the cropland areas to ensure a comprehensive and unbiased sample. The random sampling was applied within the boundaries of the cropland basemap to accurately reflect the spatial distribution of cropland in Inner Mongolia. This method ensured that the points were evenly spread throughout the region, covering all cropland areas included in the basemap.

-

(2)

NDVI time series curves for the entire growing season were generated for both crops and inactive cropland based on actual ground sample points within the three main agricultural natural zones of Inner Mongolia. Using phenological calendars established by experts, we identified the Key Growth Stages (KGS) during the peak growth periods for most crops, which exhibit significant differences from inactive cropland (i.e., natural vegetation). Differentiated NDVI thresholds were then established within Inner Mongolia.

-

First, we calculated the mean NDVI values for the main crops and inactive cropland during the Key Growth Stages (KGS), considering their standard errors. We selected the crop with the lowest mean NDVI value during the KGS and added the lower limit of its standard error to set the lower threshold for active cropland. Conversely, we added the upper limit of the standard error to the inactive cropland to establish the upper threshold for classifying inactive cropland samples. Detailed information is provided in Fig. 3. Based on the NDVI growth curves from real ground sample points in 2022 during the KGS, the classification thresholds between active and inactive croplands were calculated and are presented in Table 3.

Fig. 3 Table 3 The sample classification thresholds of each zone in KGS in 2022. -

Secondly, for sample points that fall between the lower bound of the active cropland threshold and the upper bound of the inactive cropland threshold, we considered them to be potentially confusing for classification and, therefore, excluded them. These thresholds were derived using the mean NDVI values during the KGS and their respective standard errors. The lower limit was based on the upper bound of the standard error for inactive croplands, and the upper limit was based on the lower bound of the standard error for active croplands, ensuring minimal overlap between the two classes. We applied these thresholds to the sample points from each year between 2016 and 2023. Based on the KGS NDVI values, and by applying these lower and upper threshold values, we categorized the samples into active (type:1) and inactive (type:0) classes.

-

-

(3)

Past research typically used binary-classified samples to categorize active and inactive croplands9,10,15,21. However, this study suggests that inactive croplands, having recovered through natural vegetation, may exhibit higher vegetation cover during the Key Growth Stages (KGS) and thus have NDVI values like those of active croplands in arid areas under severe drought stress. Therefore, we have proposed a further optimization strategy for the samples during the data production process. Active croplands exhibit a sharp decline in NDVI during the crop harvesting period, whereas even poorly growing crops in rainfed fields in arid areas undergo harvesting activities. In contrast, inactive croplands do not undergo harvesting activities during the main crop harvest period, so their NDVI does not show the significant declines observed in crops.

-

Through analyzing the organized phenological calendar, we found that the harvest periods for most crops in Inner Mongolia are concentrated between late July and October. Therefore, this period is the ideal window for observing crop harvesting behavior and distinguishing between inactive and active croplands (referred to as the Ideal Window Stage, IWS). By monitoring during the IWS, we identified spring wheat as the earliest harvested crop and sugar beet as the latest, with this harvest period spanning from mid-July to mid-October (details in Table S2). In Inner Mongolia, where the successive harvesting of crops occurs later, even weeds on inactive croplands undergo natural senescence during this period, leading to a decline in NDVI values. Therefore, the magnitude of NDVI reduction becomes a crucial indicator for determining the occurrence of harvesting activities and distinguishing between active and inactive croplands.

-

After determining the IWS, we calculated the NDVI curves of real ground sample points for both crops and inactive croplands within the IWS using linear fitting. Using the least squares method, we calculated the slope \(m\) and intercept \(b\) of the line, which can be expressed as \(y={mx}+b\). With this formula, we derived the slope thresholds for active and inactive croplands based on real ground sample points within the IWS. We then wrote code in GEE to export the slopes of the preliminary sample points post-binary classification during the IWS. Since the calculated slopes were quite small, we multiplied the slopes by a factor of 1000 to avoid issues with floating-point operations, thus making them more suitable for quan5titative analysis and machine learning processing.

The formulas for calculating the slope \(m\) and intercept \(b\) are as follows:

$$m=\frac{n(\sum {xy})-(\sum x)(\sum y)}{n(\sum {x}^{2})-{(\sum x)}^{2}}$$(1)$$b=\frac{\sum y-m\left(\sum x\right)}{n}$$(2)Where, \(n\) represents the number of data points, and \(x\) and \(y\) are the coordinate values of the corresponding data points.

We calculated the NDVI slopes for each type of crop and inactive cropland within the IWS across the three agricultural natural zones, as shown in Fig. 4:

-

In this step, we assigned a value of 0 to sample points with a positive NDVI slope, indicating an increase in NDVI during the IWS, which is generally unlikely for crops unless it involves inactive croplands. Conversely, those with negative slopes advanced to the next phase of sample optimization. Based on the established slope thresholds, we reassigned the samples: points with slopes above the threshold (noting all slopes are negative) were assigned a value of 0, indicating inactive cropland. Points with slopes below the threshold received a value of 1 (active cropland), suggesting these sample points experienced a significant decrease in NDVI during the IWS and were thus likely active croplands. We established three different thresholds to distinguish between active and inactive croplands within the three natural zones of Inner Mongolia (as shown in Table 4) and applied the steps and operations to sample points in each zone.

Table 4 NDVI slope thresholds within the IWS for three agricultural natural zones, derived from real ground sample points.

-

-

(4)

After completing the above steps, the sample point data now includes two ‘type’ columns, with ‘0’ representing inactive cropland and ‘1’ representing active cropland. By comparing the ‘type’ values in both columns, we retained those sample points where the values matched, thus eliminating samples that could potentially confuse the subsequent training of machine learning models. To ensure the robustness and accuracy of the classification, we adopted a conservative strategy when selecting the final sample points. This approach prioritized retaining only those points that showed consistent and reliable characteristics, reducing the risk of misclassification in the training process. As a result, we kept only those sample points that met the criteria set in steps (2) and (3) and exhibited high-quality, distinctive characteristics, ensuring that the training data would provide a solid foundation for accurate model performance.

-

(5)

After obtaining the optimized samples, we found that the number of inactive cropland samples was significantly lower than that of active cropland, leading to a class imbalance during model training. This imbalance could result in the model performing better at identifying active rather than inactive cropland. In GEE, we implemented a spatial enhancement by increasing the number of inactive cropland samples fivefold. We used a 3 × 3 kernel function to randomly generate five new points around each original sample point, ensuring a better balance between active and inactive cropland samples. This enhanced set of samples was then combined with the original points to create the final training set. These enhanced samples were then merged with the original samples to create a final sample set of both active and inactive croplands. This approach will improve the quality and fairness of model training, as it enables the model to learn from a more balanced dataset and better generalize across different types of data.

Through the five steps outlined above, we successfully generated a high-quality, distinctive sample set that distinguishes between active and inactive croplands annually from 2016 to 2023 within the three agricultural zones of Inner Mongolia as shown in Fig. S1. Ultimately, we obtained a stable set of sample datasets that provide reliable data for subsequent cropland classification and monitoring.

Classification of active and inactive cropland

Constructing classification metrics

To classify cropland activity from 2016 to 2023, we constructed a feature stack based on Sentinel-1/2 data, which includes the following features:

-

(1)

Texture features provide crucial information by analyzing the spatial organization and structure of surface materials, thereby enhancing the accuracy of land use classification. In this study, we used the following texture measures derived from Sentinel-2 Band 8 (near-infrared) data (see Table S3 in the supplementary materials): B8_idm (Inverse Difference Moment), B8_ent (Entropy), B8_asm (Angular Second Moment), B8_contrast (Contrast), B8_corr (Correlation), and B8_diss (Dissimilarity).

-

(2)

These texture measures were selected for their ability to capture spatial patterns in surface materials, contributing to improved classification accuracy in land use studies.

-

(3)

Elevation and Slope information from DEM: By analyzing elevation and slope, we can distinguish between cultivated and uncultivated croplands, as active croplands are usually located in flatter areas, while fallow or abandonment croplands usually situated on relatively higher or steeper terrains32,33.

-

(4)

Vegetation Indices: These include NDVI34, EVI (Enhanced Vegetation Index)35, NBR (Normalized Burn Ratio)36, BSI (Bare Soil Index)8, and SAVI (Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index)37. These indices reflect the health and growth status of vegetation and assist in differentiating various types of croplands8,38.

-

(5)

Tasseled Cap Wetness Greenness Difference (TCWGD)2: This serves as a crucial indicator for distinguishing between cultivated and uncultivated croplands. Active croplands typically show higher greenness due to crop growth, and irrigation or natural precipitation can also increase soil moisture in these areas, especially during the growing season. In contrast, inactive croplands may exhibit low greenness and moisture due to the absence of or minimal natural vegetation and potentially drier soils.

-

(6)

Sentinel-1 Data: Its C-band Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) can observe under all weather conditions, including cloud cover and rain, making it a valuable data source for monitoring areas with dense cloud cover. Unlike Sentinel-2, which operates best in clear weather, Sentinel-1 SAR data can continuously monitor surface conditions, filling data gaps caused by weather changes. Particularly, the data provided by VV and VH polarization modes can estimate soil moisture; wet soils lead to stronger radar signal reflections, while dry soils reflect less. Additionally, the Radar Vegetation Index (RVI)39 is sensitive to vegetation cover and is also used as an important classification metric based on SAR data.

The detailed information and annotations of these features can be found in Table S3.

Random forest classifier

After acquiring high-quality samples for large-scale mapping in Inner Mongolia and generating a comprehensive feature stack from Sentinel-1/2 data, we utilized a RF classifier40 in GEE to classify cropland activity from 2016 to 2023. The RF classifier was selected for its robustness in handling large datasets, reducing overfitting, and effectively processing multidimensional data without sacrificing performance41. We configured the model with 100 decision trees, as increasing the number of trees further yielded negligible improvements in accuracy. This setup balanced computational efficiency with high classification accuracy, making it ideal for our purposes.

Each year’s classification was performed individually, with the RF classifier leveraging the feature stack derived from Sentinel-1/2 data. For sampling, we divided each year’s dataset into training and validation sets, allocating 70% for training and 30% for validation. This approach ensured reliable classification results and produced a well-integrated, temporally consistent dataset across the study period.

Using classification metrics and training the Random Forest (RF) model, we generated annual maps of active and inactive croplands in Inner Mongolia from 2016 to 2023, as shown in Fig. 5. Such temporal maps serve as foundational data for subsequent production of abandoned and reclaimed cropland products.

Temporal segmentation of abandoned and reclaimed cropland

Existing studies have utilized satellite remote sensing technology and multi-year data overlay methods based on time windows to monitor and quantify cropland abandonment3,10,13,14. These techniques provide essential tools for long-term monitoring of land use changes. Building on previous research, this study further optimizes and extends the existing “Time-Sliding Window” method to enhance the monitoring of abandoned cropland in specific regions, such as Inner Mongolia. We developed an approach using active and inactive cropland maps generated from Sentinel-1/2 data from 2016 to 2023 to comprehensively monitor the active status of croplands and capture diverse land use changes. Initially, we classified on a spatial scale, then tracked land use trajectories through the time-sliding window, and precisely extracted abandoned croplands. We defined croplands that have not been cultivated for more than two years as abandoned, setting this period at three years for our analysis. By incorporating annual cropland usage maps into the time-sliding window, we established a three-year period as the time window to extract the dataset of abandoned croplands from 2016 to 2023. Additionally, we monitored reclaimed croplands. Specifically, if a pixel, after being designated as abandoned, transitions back to an active state within the following two years, it is considered reclaimed. If it does not remain actively cultivated, it is deemed unstable and continues to be analyzed through the time-sliding window. This process is illustrated in Fig. 6.

This method allows for the adjustment of the time window’s length according to actual needs and for modification of the analysis start and end years based on the dataset’s capacity. Through this approach, we not only generated maps of abandoned and reclaimed croplands from 2016 to 2023 but also detailed the distribution of cropland pixels that remained in a state of abandonment, as well as those that were stably cultivated and unstable during this period.

Data Records

The cropland utilization dataset for Inner Mongolia, China, from 2016 to 2023, consists of four distinct groups, each designed to provide detailed insights into cropland dynamics over this period:

-

1.

Annual Cropland Activity Dataset (ARCC10-IM-ACA): This dataset contains 10-meter resolution maps that detail the annual cropland activity in Inner Mongolia from 2016 to 2023. It includes eight cropland activity maps, showing active and inactive croplands, along with the sample points used for classification each year (as shown in Fig. 5). Each map classifies cropland as either active or inactive. Sample points are categorized as either {type 0: inactive cropland} or {type 1: active cropland}.

-

2.

Abandoned Cropland Dataset (ARCC10-IM-AC): This dataset identifies croplands that have been abandoned each year, based on the annual cropland activity maps and a spatio-temporal segmentation algorithm.

-

3.

Reclaimed Cropland Dataset (ARCC10-IM-RC): Like the abandoned cropland dataset, this dataset identifies reclaimed croplands annually, also using the spatio-temporal segmentation algorithm applied to the annual cropland activity maps.

-

4.

Cumulative Land Use Dataset (ARCC10-IM-CLU): This dataset overlays the annual cropland activity data from 2016 to 2023 using a spatio-temporal segmentation algorithm. It categorizes cropland areas as:

-

{1: continuously abandoned during 2016–2023}

-

{2: remained unstable during 2016–2023}

-

{3: remained active during 2016–2023} These classifications provide insights into long-term cropland use and abandonment trends, as shown in Fig. 9.

All datasets are stored in GeoTIFF format and are available in the Figshare repository42. They use the EPSG: 4326 (WGS_1984) spatial reference system.

Technical Validation

Validation of annual cropland classification maps

We utilized 70% of the derived samples as training samples, employing the GEE-RF to train on annual land use activities, while the remaining 30% served as validation samples to assess the classification’s accuracy. In developing our accuracy assessment strategy, we used accuracy metrics derived from the confusion matrix to measure the classification’s precision. Following the recommendations of Foody et al.43 and Olofsson et al.27 in the accuracy assessment of land use classification, we prefer to use Overall Accuracy (OA), Producer’s Accuracy (PA), User’s Accuracy (UA), and the F1 score. The F1 score is calculated as F1 = 2 × (UA × PA) / (UA + PA), with the specific formulas for OA, PA, and UA detailed in Equations 3 to 5. Additionally, following the guidelines of Olofsson et al.27 for assessing land use classification accuracy, we calculated the standard error and 95% confidence intervals for PA, UA, and the F1 score. These calculations help evaluate the metrics’ reliability and stability, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of the classification results’ reliability.

Following the above accuracy validation process, we obtained the overall classification accuracy for cropland activity from 2016 to 2023, along with the Producer’s Accuracy (PA), User’s Accuracy (UA), and F1 score for active and inactive croplands, and their 95% confidence intervals. The validation was conducted based on the final sample dataset, which underwent sample enhancement for inactive croplands. This strategy helped mitigate the issue of imbalanced datasets, improving the classification accuracy for inactive croplands. The validation results are presented in Fig. 7, which illustrates the annual accuracy metrics.

Our results demonstrate that using the optimized samples and enhanced inactive cropland samples significantly improved the UA and PA for inactive cropland. This highlights the importance of sample enhancement in reducing classification bias and improving the model’s ability to recognize minority classes, such as inactive croplands.

Based on these validation results, we selected the samples generated under the optimized strategy to create the final annual cropland activity classification dataset from 2016 to 2023. Using this dataset as a baseline, we applied a temporal segmentation method to identify abandoned and reclaimed croplands over the time series. This method allowed us to generate a dataset detailing the dynamic changes of croplands between active cultivation, unstable fallowing, continuous abandonment, and reclamation from 2016 to 2023, as shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 9 reveals that currently, 30.65% of the cropland in Inner Mongolia is in a somewhat unstable state, meaning that between 2016 and 2023, it was not consistently in stable cultivation. The proportion of land under stable cultivation is 69.21%. Additionally, this unstable fallow land is widely spread across all zones, including the SHZ, SAZ, and AZ, indicating ongoing challenges in cropland management in Inner Mongolia. On the other hand, the cropland that has remained uncultivated from 2016 to 2023, classified as abandoned, constitutes only 0.14% of the total cropland area in Inner Mongolia—a very small fraction. This reduction in abandoned croplands can be attributed to the tightening of cropland management policies in recent years and the initiation of government-led projects such as the development of high-standard farmlands, which have mitigated the issue of cropland abandonment.

Validating the accuracy using ground truth reference samples

Olofsson et al.27 suggest that for good practice in accuracy validation of land use classification results, it is best to use a reference dataset that has higher resolution or reflects the actual ground situation of land use. Taking this advice into consideration, we used the main crop and inactive cropland sample points collected in 2022 and 2023 to further validate the classification results. However, due to a significant discrepancy between the number of real ground-collected samples and the derived samples in GEE, we treated them as a reference outcome, assessing the accuracy of the classification results from another perspective.

Specifically, we overlaid the active and inactive cropland sample points from 2022 and 2023 onto the cropland classification results for those respective years and extracted the attributes of the sample points on the resulting maps. We then constructed confusion matrices based on the number of correctly and incorrectly classified samples and derived accuracy metrics such as PA, UA, and the F1 score from these matrices. Finally, utilizing the methods and equations introduced in the previous section, we calculated the standard error to obtain the 95% confidence intervals for each accuracy metric, with the specific results displayed in Fig. 10.

The accuracy validation results from the actual ground sample points for 2022 and 2023 show that after optimizing the active and inactive cropland samples using NDVI slope and enhancing the small sample set, a higher classification accuracy was achieved: 83.48% overall accuracy for 2022 and 78.16% for 2023, as displayed in Fig. 10(a). This indicates that both overall classification accuracy and the prediction proportion for each class are high, demonstrating the model’s good performance overall. As shown in Fig. 10(b), although the optimized samples for the 2022 data show an improvement in classification accuracy over the unoptimized samples, the increase is not significant. However, the results for 2023 show that despite a lower OA due to the smaller total number of samples, there is no significant difference between the UA and PA due to a more balanced sample size between inactive and active cropland. Moreover, there was a significant improvement in classification accuracy before and after optimization.

Comparisons with China-CUI10m product

The ChinaCUI10m dataset44 provides annual cropland use data from 2018 to 2021. When comparing this dataset with the ARCC10-IM-ACA data for the corresponding years, we found that the proportion of pixels identified as active cropland globally exceeds 90% in all four years as shown in Fig. 11. This indicates a high level of consistency in the extraction of active cropland between the two datasets. For inactive cropland, the proportions consistently classified as inactive in both datasets for 2018 to 2021 were 2.28%, 0.84%, 0.94%, and 0.85%, respectively. Although these percentages are relatively small, this is due to the low overall proportion of inactive cropland during those years—only 2% to 4% of the total cropland area, as shown in Fig. 5. Additionally, the discrepancy between the two datasets, where the classification results differ, ranged from 5% to 6%. In these cases, ChinaCUI10m tended to classify certain fields as fallow while ARCC10-IM classified them as active cropland, with the reverse scenario being less common. The producer’s accuracy for fallow cropland in ChinaCUI10m is 0.88, slightly lower than that of the ARCC10-IM dataset.

It is important to note that the ChinaCUI10m dataset covers all of China45. Despite its broader spatial scope, ChinaCUI10m still shows a high degree of agreement with ARCC10-IM in terms of extracting active cropland, highlighting the effectiveness of both methods in this task. On the other hand, ARCC10-IM focuses specifically on Inner Mongolia, offering higher spatial resolution and regional adaptability, which allows it to capture more detailed cropland changes, particularly in small, fragmented fields and rapidly changing land-use regions. For inactive cropland, the area where both datasets agreed was about half of the actual inactive cropland. This is because the ARCC10-IM dataset was able to capture finer details in cropland changes, especially in marginal and fragmented plots that are difficult to detect on a larger scale. Non-active cropland, particularly fallow and abandoned land, often occurs in such marginal and fragmented areas, which are harder to detect at a larger spatial scale. The ARCC10-IM dataset’s use of regional-scale automated sample generation and classification supports more accurate detection of these plots, yielding more reliable data.

To demonstrate the advantages of the ARCC10-IM data, we included snapshots (Fig. 12) that show how it achieves higher precision in extracting fallow land in small parcels, underscoring its superiority in detecting complex land-use changes in fragmented fields.

Comparison of cropland activity between the ARCC10-IM dataset and ChinaCUI10m in Inner Mongolia (2018–2021). Sentinel-2 false-color composite images are used in the background, generated from GEE by averaging data between June 15 and August 15, which corresponds to the peak growth period before crop harvesting. In the false-color images, gray-green areas represent fallow croplands where no crops are present, while bright red areas indicate active croplands with significant vegetation cover.

Usage Notes

The ARCC10-IM (Abandoned and Reclaimed Cropland Classification at 10-meter resolution in Inner Mongolia) dataset40 provides detailed annual maps from 2016 to 2023, offering crucial insights into cropland dynamics in Inner Mongolia. The dataset distinguishes between active croplands, abandoned lands, and reclaimed areas, making it essential for monitoring agricultural trends and assessing land management strategies.

-

This high-resolution dataset supports a range of applications, including:

-

Agricultural planning and land use policy analysis

-

Monitoring land degradation, fallow periods, and reclamation efforts

-

Evaluating agricultural productivity and food security policies

Given the growing need for sustainable agricultural practices, ARCC10-IM enables researchers and policymakers to assess the effectiveness of strategies aimed at preventing cropland abandonment and promoting sustainable land use. The dataset also allows users to track long-term changes in cropland activity, providing valuable data for addressing environmental and socio-economic challenges in arid and semi-arid regions like Inner Mongolia.

The dataset is stored in Geotiff format and is available on Figshare40, offering a practical tool for land management, environmental assessments, and agricultural studies.

Code availability

We provide three distinct scripts: one employing a RF classifier to categorize active and inactive croplands, another that segments annual cropland activity maps over time, and a third that exports NDVI values and slope measurements for specific time periods. All scripts are developed using the GEE JavaScript API, enabling their execution within the Earth Engine Code Editor. They are thoroughly documented with detailed comments to aid users in understanding and customizing the code to their specific needs. The script for temporal segmentation allows users to adjust parameters to suit their needs, facilitating the generation of datasets for abandoned and reclaimed croplands over various time spans. The analysis scripts used in this study are also available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25687278.v4.

References

Cui, Y. et al. Decoding the Inconsistency of Six Cropland Maps in China. The Crop Journal 12, 281–294 (2024).

Gibbs, H. K. & Salmon, J. M. Mapping the World’s Degraded Lands. Applied Geography 57, 12–21 (2015).

Zheng, Q. et al. The Neglected Role of Abandoned Cropland in Supporting both Food Security and Climate Change Mitigation. Nature Communications 14, 6083 (2023).

Guo, A. et al. Cropland Abandonment in China: Patterns, Drivers, and Implications for Food Security. Journal of Cleaner Production 418, 138154 (2023).

Zhang, M. et al. Reveal the Severe Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Abandoned Cropland in China over the Past 30 Years. Science of the Total Environment 857, 159591 (2023).

Wuyun, D. et al. Mapping Fallow Fields using Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Archives over Farming-Pastoral Ecotone of Northern China with Google Earth Engine. GIScience & Remote Sensing 59, 333–353 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Satellite-Based Observations of the Green Depressing Cropping System in a Farming-Pastoral Ecotone of Northern China. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 98, 102312 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. Is Abandoned Cropland Continuously Growing in China? Quantitative Evidence and Enlightenment from Landsat-Derived Annual China Land Cover Dataset. Land 13, 45 (2024).

Dara, A. et al. Mapping the Timing of Cropland Abandonment and Recultivation in Northern Kazakhstan using Annual Landsat Time Series. Remote Sensing of Environment 213, 49–60 (2018).

Yin, H. et al. Monitoring Cropland Abandonment with Landsat Time Series. Remote Sensing of Environment 246, 111873 (2020).

Shi, K. et al. Mapping and Evaluating Cultivated Land Fallow in Southwest China using Multisource Data. Science of The Total Environment 654, 987–999 (2019).

Hong, C. et al. Mapping Cropland Abandonment and Distinguishing from Intentional Afforestation with Landsat Time Series. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 127, 103693 (2024).

Ren, W. et al. Spatial Patterns, Drivers, and Sustainable Utilization of Terrace Abandonment in Mountainous Areas of Southwest China. Land 13, 283 (2024).

Long, Y. et al. Mapping the Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Cropland Abandonment and Recultivation across the Yangtze River Basin. Remote Sensing 16, 1052 (2024).

Tu, Y. et al. A 30 m Annual Cropland Dataset of China from 1986 to 2021. Earth System Science Data Discussions, 1-34 (2023).

Su, Y. et al. Monitoring Cropland Abandonment in Southern China from 1992 to 2020 Based on the Combination of Phenological and Time-Series Algorithm Using Landsat Imagery and Google Earth Engine. Remote Sensing 15, 669 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Mapping Abandoned Cropland Changes in the Hilly and Gully Region of the Loess Plateau in China. Land 10, 1341 (2021).

Yin, F. et al. Determinants of changes in harvested area and yields of major crops in China. Food Security 16, 339–351 (2024).

CSIS (Center for Strategic and International Studies). “China’s Food Security: Key Challenges and Emerging Policy Responses.” Accessed January 2, https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-food-security-key-challenges-and-emerging-policy-responses (2024).

Gorelick, N. et al. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-Scale Geospatial Analysis for Everyone. Remote Sensing of Environment 202, 18–27 (2017).

Tong, X. et al. The Forgotten Land Use Class: Mapping of Fallow Fields across the Sahel using Sentinel-2. Remote Sensing of Environment 239, 111598 (2020).

Movahedi, R. et al. Why do Farmers Abandon Agricultural Lands? The Case of Western Iran. Land Use Policy 108, 105588 (2021).

Zanaga, D. et al. ESA WorldCover 10 m 2020 v100 (2021).

Chaudhary, S. et al. A Synopsis of Farmland Abandonment and Its Driving Factors in Nepal. Land 9, 84 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Unveiling the Effect of Land Transfer and Land Acquisition on Farmland Abandonment: Proximity/Distance to the City Matters. Applied Geography 163, 103181 (2024).

Quintas-Soriano, C. et al. Effects of Land Abandonment on Nature Contributions to People and Good Quality of Life Components in the Mediterranean Region: A Review. Land Use Policy 116, 106053 (2022).

Olofsson, P. et al. Good Practices for Estimating Area and Assessing Accuracy of Land Change. Remote Sensing of Environment 148, 42–57 (2014).

Amazirh, A. et al. Retrieving Surface Soil Moisture at High Spatio-Temporal Resolution from a Synergy between Sentinel-1 Radar and Landsat Thermal Data: A Study Case over Bare Soil. Remote Sensing of Environment 211, 321–337 (2018).

Patel, P. et al. Comparative Evaluation of the Sensitivity of Multi‐Polarized Multi‐Frequency SAR Backscatter to Plant Density. International Journal of Remote Sensing 27, 293–305 (2006).

Haddaway, N. R. et al. Environmental Impacts of Farm Land Abandonment in High Altitude/Mountain Regions: A Systematic Map of the Evidence. Environmental Evidence 2, 18 (2013).

Farr, T. G. et al. The Shuttle Radar Topography Mission. Reviews of Geophysics 45, 1–13 (2007).

Haralick, R. M. et al. Textural Features for Image Classification. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 6, 610–621 (1973).

Perpiña Castillo, C. et al. An Assessment and Spatial Modelling of Agricultural Land Abandonment in Spain (2015–2030). Sustainability 12, 560 (2020).

Rouse, J. W. et al. Monitoring Vegetation Systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. NASA Special Publications 351, 309 (1973).

Key, C.H. et al. Landscape Assessment: Ground Measure of Severity, the Composite Burn Index; and Remote Sensing of Severity, the Normalized Burn Ratio. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. USGS Publications Warehouse (2006).

Huete, A. et al. Overview of the Radiometric and Biophysical Performance of the MODIS Vegetation Indices. Remote Sensing of Environment 83, 195–213 (2002).

Huete, A. R. et al. A Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI). Remote Sensing of Environment 25, 295–309 (1988).

Yin, H. et al. Mapping Agricultural Land Abandonment from Spatial and Temporal Segmentation of Landsat Time Series. Remote Sensing of Environment 210, 12–24 (2018).

Kim, Y. et al. Radar Vegetation Index for Estimating the Vegetation Water Content of Rice and Soybean. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 9, 564–568 (2012).

Breiman, L. et al. Random Forests. Machine Learning 45, 5–32 (2001).

Pelletier, C. et al. Assessing the Robustness of Random Forests to Map Land Cover with High Resolution Satellite Image Time Series over Large Areas. Remote Sensing of Environment 187, 156–168 (2016).

Wuyun, D. et al. A 10-meter annual cropland activity map and dataset of abandonment and reclaimed cropland. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25687278.v4 (2024).

Foody, G. M. Status of Land Cover Classification Accuracy Assessment. Remote Sensing of Environment 80, 185–201 (2002).

Qiu, B. et al. National-scale 10-m maps of cropland use intensity in China during 2018–2023. Scientific Data 11, 691 (2024).

Qiu, B. et al. National-scale 10-m maps of cropland use intensity in China during 2018–2023. figshare. (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2023YFD2000100). We would also like to express our sincere appreciation to the two anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback, and to Mengqi Duan for providing helpful suggestions during the revision process, both of which have significantly improved the quality of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.W. and L.S. designed the study; M.H., Y.L., Z.S. and H.Z. performed the analysis; D.W. drafted the manuscript; Z.C. and T.R. contributed to revising the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wuyun, D., Sun, L., Chen, Z. et al. A 10-meter resolution dataset of abandoned and reclaimed cropland from 2016 to 2023 in Inner Mongolia, China. Sci Data 12, 317 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04614-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04614-8