Abstract

This paper introduces a new Czech Political Candidate Dataset (CPCD), which compiles comprehensive data on all candidates who have run in any municipal, regional, national, and/or European Parliament election in the Czech Republic since 1993. For each candidate, the CPCD includes their first name, last name, age, gender, place of residence, university degree, party membership, party affiliation, ballot position, and election results for candidates and for parties. We match candidates over various elections by using algorithms that rely on their personal information. We add information on political donations made to political parties. We source donation information from the Czech Political Donation Dataset (CPDD), our other newly built dataset, in which we compile records of individual donations to 12 leading political parties from official records for the period from 2017 to 2023. CPDD is publicly available along with the CPCD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The Czech Republic is a democratic unitary state structured into three levels of governance: municipalities (obce), regions (kraje), and the central government. Citizens thus participate in municipal, regional, and national parliamentary elections (the Czech parliament is bicameral, and the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate hold separate elections). With the introduction of European Parliament elections in 2004 and presidential elections in 2013, the frequency of elections has increased. The Senate and presidential elections operate on a two-round majority electoral system, while other elections employ a flexible list proportional representation system with large constituencies. In the flexible list system, voters influence the order of candidates on the party list by casting preference votes, effectively personalizing the elections, as votes for individual candidates impact seat distribution within parties. This institutional framework provides a rich context for studying political selection, candidate performance, multiple office holding, and political career trajectories across various elections and offices. The Czech Statistical Office (CZSO), which is in charge of processing all election results, facilitates such research by publishing official electoral results (including information about candidates stated on ballot lists) as open data immediately after each election. However, unlike, for example, Sweden, where candidates are assigned unique identifiers for traceability across elections1, the CZSO does not assign candidates such identifiers. Candidates thus cannot be easily tracked across years and types of elections. To address this issue and enhance research capabilities, we build a Czech Political Candidate Dataset (CPCD), which matches candidates across years and types of elections, consolidating data on candidates and district-level election results into a single, comprehensive dataset.

The CPCD offers candidate-level data that includes everyone who has run in any municipal, regional, national, and/or European Parliament election in the Czech Republic since the establishment of the independent state in 1993. The core variables provided by the CZSO include the candidate’s first and last names, age, place of residence, academic title, party affiliation, ballot position, and election outcomes for candidates and for parties. By employing an algorithm that integrates information on first and last names, year of birth, and place of residence, we merge individual candidates across different years and types of elections. This results in an unbalanced panel data structure in which candidates are observed multiple times, reflecting the number of elections they participated in. Overall, the dataset includes 841,565 unique candidates, and a total of 1,716,471 candidate-election observations. By providing this information, the CPCD aligns with similar datasets created for Norwegian2 and European Parliament elections3.

Additionally, we extract information on candidates’ gender and education level from the details provided on ballot lists. To identify candidates’ gender, we use name dictionaries and surname endings, and determine educational attainment using a dictionary of university degrees and academic titles. We further enhance the candidate data by linking it with data on donations made by individual candidates. This information is sourced from our newly developed Czech Political Donation Dataset (CPDD), in which we compile records of individual donations to political parties. We make this database publicly available along with the CPCD. We obtained the primary donation data, covering the period from 2017 to 2023, from the Office for Supervision of Economic Affairs of Political Parties and Political Movements (OSEAPPPM). After cleaning the data, we match donors to a party and political candidates using their full name and birth year information.

The data on Czech political candidates provided by CZSO have been extensively used in previous research. Scholars have focused on party nomination strategies4, partisan structure of candidates5,6,7, party switching among candidates6, the number of women among candidates and elected officials8,9, multiple office holders10, preference voting11,12, ballot-order effects13,14, uncontested elections7,15,16, and electoral17 and ruling coalition formation18. Another stream of research uses information on municipal candidates and analyses the effect of political donations on party nomination strategies in municipal elections19 and on the allocation of public procurement contracts20,21, the effect of political representation on public procurement22 and on budget allocation23,24, and the effect of political salaries on electoral competition and incumbency advantage25. Additionally, research into democratic accountability link uses candidate data from national elections and matches them with information on MP’s parliamentary activities (oral questions, bill sponsorship, speeches, voting participation) and party discipline to investigate the links between parliamentary work, re-selection, and re-election26,27,28,29. The datasets we make publicly available should facilitate further electoral research and help academics to broaden their focus by (1) linking candidates across different elections and different types of elections, (2) providing transparent and verified variables for gender and educational attainment, and (3) matching political candidates and donors to political parties.

Methods

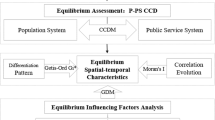

This paper introduces two newly created datasets: the Czech Political Candidate Dataset (CPCD) and the Czech Political Donation Dataset (CPDD). We created the CPCD by processing and standardizing official electoral data provided by the CZSO. It combines primary datasets for each election: municipal, regional, national (Chamber of Deputies and the Senate), and European Parliament (presidential elections are not included). We then linked information about individual candidates across elections by matching the candidates.

The CPDD provides information on individual donations to the last decade’s 12 most prominent political parties. We downloaded the primary datasets from the Office for Supervision of Economic Affairs of Political Parties and Political Movements (OSEAPPPM), hand-cleaned, and merged them across years. The available data covers the period from 2017, when the OSEAPPPM was established, to 2023. We then matched this donation dataset to the CPCD using donors’ names and birth years.

Because the preparation of datasets requires work with personal information including full names, birth dates, place of residence, and financial donations, we requested an ethics evaluation of this project. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University (Approval No. 135).

In this section, we first provide institutional background for each election type to clarify the details of Czech elected offices and electoral systems. Then, we describe our acquisition of primary data sources, standardization of variables, and how we matched them across elections (candidates) and years (donations). Finally, we describe the linking of candidates with the donations dataset.

Institutional background

The Czech Republic operates under a parliamentary system with a bicameral legislature consisting of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. The Chamber of Deputies has greater political power. It decides on the government through votes of confidence, it approves the annual state budget, and a majority of MPs can outvote a Senate and/or Presidential veto on bills.

The Czech Republic has two levels of territorial self-governance: municipalities and regions. On January 1, 2024, there were 6,254 municipalities, with an average population of 1,743 residents per municipality with the median being 45230. Municipalities are primarily responsible for local development and spatial planning, municipal policing, water supply and sewage management, waste management, public transportation, preschools, primary and lower secondary education, and social services. This structure grants a medium degree of local autonomy compared to other democratic countries, particularly in Europe31. Large cities can be organized into municipal districts, each with its own autonomy, elected bodies, and administration. As of the 2022 municipal elections, eight cities have adopted this structure, forming 140 sub-municipal units. The municipal assembly (zastupitelstvo obce) is responsible for electing a mayor (starosta obce) and a municipal committee (rada obce, similar to aldermen in some European countries) through a majority vote. However, a municipal committee is not established if the municipal assembly has fewer than 15 members. The same rules apply to municipal districts. In the capital city of Prague, elections are organized according to the municipal election rules.

The regional level of governance was introduced in 2000, when the first elections to regional assemblies were held. Regional elections are held in 13 regions. The regional level of governance is responsible for regional development, road networks, transport, tourism, health care, upper-secondary education, and environmental protection. Regional governments are politically weak and have little financial autonomy. This translates into a low level on the Regional Authority Index32. Regional assemblies (krajské zastupitelstvo) elect governors (hejtman kraje) and regional committees (rada kraje) by majority vote.

Elections to municipalities, regions, the Chamber of Deputies, and the European Parliament follow almost identical electoral rules: a flexible list proportional representation (PR) system with similar electoral formulae, thresholds, and large constituencies. Only Senate elections are held under a two-round majority electoral system. Table 1 summarizes the basic features of electoral systems. Nomination rules are also broadly similar across elections. Because Czech democracy is primarily constructed as a party democracy, only registered parties and their coalitions nominate candidates. Parties also determine the rank of their candidates on the ballot. It is possible for independent candidates to run in municipal and Senate elections. In municipal elections, independent candidates and their associations are registered after they submit a petition supporting their candidacy signed by 7 percent of registered voters (the requirements are lower for an individual candidate). In Senate elections, independent candidates are enrolled after they submit a petition supporting the candidate signed by 1,000 registered voters residing in the constituency.

In all elections held under the proportional representation system in the Czech Republic, party ranking and preference votes co-determine the final order of candidates on the electoral list. In all elections, preferential voting is voluntary. The number of preference votes and the threshold for jumping up the candidate list varies across elections and have changed over time (see Table 1 for more details). In municipal elections, the preference voting rules differ from other elections, as voters can support various candidates across different ballots. Voters have the same number of votes as the number of elected representatives and have three options for how to use their votes: (1.) They can choose one party and allocate all their votes to that party; in that case, each candidate receives 1 vote; (2.) They can tick individual candidates across the party lists; or (3.) They can combine the two options: tick candidates across party lists and then give the rest of the votes to their preferred party. In the latter case, the votes given to the party are distributed to candidates in sequence from the top of the list. Due to the mechanical redistribution of votes towards better-ranked candidates, the votes received cannot be interpreted as pure preference votes. The threshold for moving to the top of the list is set to 110% of the average number of votes for all candidates on the party list.

Czech Political Candidate Dataset

To generate this dataset, we follow these steps: downloading primary datasets, creating candidate datasets for each election (election-specific datasets), transforming variables, and matching candidates across election types (election-type datasets) and across all elections (the final dataset).

For each election, we downloaded the primary datasets from the official website of the CZSO (https://volby.cz/opendata/opendata.htm). Data on the 1996 and 1998 Chamber of Deputies elections and the 1994 and 1998 municipal elections are not available as open source and were provided to us by the CZSO upon a formal request. The primary datasets include information on:

-

characteristics of candidates derived from ballot lists;

-

electoral results for each candidate and party at the constituency level;

-

list of registered political parties and list of parties and electoral coalitions running in elections.

As a first step, we created election-specific datasets, which combine information from primary datasets for each election. The unit of observation is an individual candidate for whom we record (1.) variables common to all types of elections (e.g., candidates’ characteristics, party affiliation) and (2.) election-specific variables (e.g., constituency names and codes, party composition of the list for municipal elections). For each candidate, we record their first name, last name, age, place of residence, academic titles, party membership, party affiliation, ballot position, number of (preference) votes received, whether the candidate was elected, and the number of votes for the candidate’s party. In the process of building election-specific datasets, we created three new variables: candidate_education, candidate_gender, and candidate_birthyear. We describe all variables in the Data records section. We kept original variables from primary datasets for transparency while preparing the final dataset, so the CPCD contains both original and newly created variables.

After standardizing election-specific datasets, we merged files for the same type of elections over the years and created 6 election-type datasets: municipal districts, municipalities, regions, the Chamber of Deputies, the Senate, and the European Parliament. We then merged election-type datasets into the final dataset. To match candidates, we use deterministic matching that compares pairs of candidates from different elections based on their first name, last name, year of birth, place of residence, education, occupation, party membership, and nominating party. Candidates must pass a threshold to be matched, which is based on the similarity of records in the variables. Not all variables are treated equally; pairs of candidates with the same name are graded based on the correspondence in values, with first name, last name, and year of birth having the largest effect. In addition, first and last names are used as blocking variables, meaning that they must be equal for the candidate records to match. If two or more candidates share the same first and last name and the same year of birth, then candidates’ education, occupation, party membership, and nominating party are used. The correspondence of these variables is judged by equality, except for occupation, in which string distance is used. To adjust for seasonal variability of the election dates, the birth year—calculated as the difference between the election year and candidates’ reported age—is allowed to deviate by one year. The above-described method may result in under-matching candidates who have changed their last names, particularly female candidates who adopt new names after marriage. To assess the potential impact, we re-ran the matching algorithm for municipal elections without using candidates’ last names as a blocking variable. In effect, we match candidates only using their first name and birth year. Under this alternative matching, the average number of elections per candidate increased slightly, from 1.960 to 1.969. The effect was more pronounced among female candidates under the age of 50, for whom the average number of elections per candidate rose from 1.795 to 1.815–a difference of 0.02. The increase was smaller for the older female candidates, growing by just 0.004 from 1.561 to 1.565. This corresponds to the increase for male candidates. These findings suggest that while some female candidates may change their last names during an active political career in municipal elections, the phenomenon does not seem widespread.

The process of merging the files and matching the candidates was sequential as we matched candidates first within the election-type datasets and later in the final dataset. This approach allows us to maximize our utilization of the information on the place of residence; in municipal (and city district) elections, candidates can only run in the municipality in which they reside. We use the municipality as a blocking variable to ensure that candidates running in a city district belonging to a municipality were matched to candidates running in the same municipality. The downside of this approach is that a candidate who has moved to a different municipality is not recognized as the same individual. In all other types of elections, candidates can run in any constituency regardless of where they live, so place of residence is not used as a blocking variable for matching candidates in these elections, and candidates who have moved are matched.

Czech Political Donation Dataset

Czech political party financing is built around direct state funding as the primary funding source for political parties, with private donations playing a moderate role and membership fees being relatively insignificant. State subsidies are provided based on national election results and the number of seats a party holds in the Chamber of Deputies, the Senate, and regional assemblies33. The dominant role of state funding is complemented by a liberal regime of private funds. While political parties are prohibited from accepting contributions from foreign sources, anonymous donors, and government-owned corporations, other donors (corporations and individual donors) were not restricted in terms of donation amounts until 2016. Since then, the cap on donations from both individual corporations and individual citizens has been set to CZK 3 million (EUR 120k) per year. Aside from general rules set forth by civil and tax codes, donations to independent candidates are not subject to specific regulations.

Individuals are allowed to make financial or non-financial donations to political parties (examples of non-financial donations include offering space for advertising banners, distributing flyers, or other types of volunteering in campaigns). Political parties must disclose a list of all donors annually, including additional individual information. Information about membership fees does not have to be disclosed unless the amount exceeds CZK 50,000 (EUR 2k) per year. At this point, a membership fee is considered a donation by law. Since 2017, a list of donors must be submitted to the Office for Supervision of Economic Affairs of Political Parties and Political Movements (OSEAPPPM) as part of annual financial reports. The OSEAPPPM is responsible for reviewing these reports and may request corrective action if inaccuracies or errors are identified, and may impose fines. However, the office lacks the means to verify the accuracy of the information provided, including information about individual donors.

We downloaded the primary data about political donations from individual donors from the OSEAPPPM https://udh.gov.cz/vyrocni-financni-zpravy-stran-a-hnuti), hand-cleaned it, and collapsed it for individual donors by year and donation type (financial and non-financial). We rely on full name, date of birth, and political party to merge the individual donors over the years. The dataset covers individual donations made between 2017 and 2023 to any political party that received at least 1.5% of votes in the 2017 or 2021 Chamber of Deputies elections. The list includes 9 parliamentary and 3 non-parliamentary parties. Among the covered years and political parties, only 9 donor lists (from the total of 78 year-political party pairs) are not provided in CSV files. For these year-political party pairs, we downloaded the PDF and extracted the information using OCR tools to digitally readable formats and then cleaned them in the same manner as the initially digitally readable formats. Our prepared deposit contains the original PDF files, intermediate CSV files, script, and final datasets for these cases.

The hand-cleaning process consists of correcting typos in names, adding missing diacritics, capitalizing the first letters, and swapping the first name and last name in cases where the typos are highly probable; if one of the names is a typical Czech first name, while the other is a typical last name.

Furthermore, we corrected the birthdates of donors. If two or more donors with the same name made a donation to the same political party, but their birthdates differ in some suspect manner, we tagged the birthdate as a typo and hand-corrected it. The three specific types of suspected typos we consider are the following. First, if the month and day were flipped (e.g., if two donors with the same names had a date of birth on July 6, 1985 (2 donations) and June 7, 1985 (1 donation), we tagged the latter as a typo and merged the donors into one with a July 6 date of birth). Second, a possible typo that changes the date of birth by exactly one digit (e.g., if two donors with the same names had a birthdate of July 6, 1985 (2 donations) and June 6, 1985 (1 donation), we tagged the latter as a typo and merged the donors into one with a birthdate of July 6). We refrained from editing for both types of typos when both versions of donors’ personal information were represented the same number of times, e.g., July 6, 1985 (1 observation) and June 6, 1985 (1 observation). Third, if the year of birth reported corresponds to the year of the donation (e.g., if two donors with the same names had a birthdate of July 6, 1985, and July 6, 2021, we corrected the latter to July 6, 1985).

From the total 78-year list of financial donations to political parties, 69 are provided in digitally readable files. These datasets contain 85,378 recorded donations (donors could make more than one donation yearly). Among those, the manual changes edited 1,253 (1.5%) last names, 1,257 (1.5%) first names, and 475 (0.6%) birthdates. Among non-financial donations, the data provided in digitally readable files contain 31,642 reported donations, and the manual edit changed 176 (0.6%) last names, 215 (0.7%) first names, and 81 birth dates (0.3%). Manual edits in datasets extracted from PDF files were more frequent, but combined edits that were triggered by typos and inaccuracies in the primary dataset and from extracting the dataset from PDF files.

Compared to a previously used dataset of Czech political donations19, CPDD covers more political parties but spans fewer years of donations. This difference arises from our deliberate choice to prioritize the use of official data submitted to the OSEAPPPM, ensuring the highest possible level of transparency. The earlier dataset was manually transcribed from physical printed documents stored in the Chamber of Deputies archives, making it difficult to replicate and verify. In contrast, the CPDD is constructed from an online, publicly accessible primary data source, allowing for easier verification and transparent replication. While this approach enhances the dataset’s credibility, it inevitably results in shorter historical coverage.

Matching the Czech Political Candidate Dataset and the Czech Political Donation Dataset

Individuals (candidates and donors) who are represented in both CPCD and CPDD have the same person_id in both datasets. We first collapsed the CPCD to the candidate level and the CPDD to the donor level. We then matched the collapsed CPCD and the CPDD based on similarity between individuals’ first and last name, year of birth, and party. The matching links unique donor ID (donor_id, defined by a unique combination of the first and last name and the year of birth) with person_id in the candidate dataset. For all donors with a counterpart in the candidate dataset, we use person_id from the candidate dataset that links the two datasets. We created a new unique ID for donors that were not matched to candidates. This approach ensures that if a candidate and a donor are identified as one individual, the observations share the same person_id.

Data Records

The CPCD and CPDD are publicly available at the Czech Social Science Data Archive (https://doi.org/10.14473/CSDA/MDZC3F)34. The datasets are available in .csv and .rds formats. The script to produce final datasets, which covers the whole process from data download to matching CPCD and CPDD is available at OSF (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/RAKJZ)35.

Czech Political Candidate Dataset

The deposit contains 6 election-type datasets and the final CPCD, which merges all candidates across elections. The CPCD contains information on 841,565 unique candidates and 1,716,471 candidate-election observations.

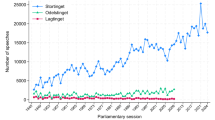

Table 2 provides statistics on the number of candidates for each election. The largest number of candidates participate in municipal elections, with an average of over 180,000 per election year. In contrast, fewer than a thousand candidates run in each Senate and European Parliament election. Several thousand candidates compete in elections for the Chamber of Deputies and in regional elections. For each election, the table further provides the number of elected representatives, the share of elected among all candidates, the number of female candidates, the number of elected female candidates, and finally, the share of female candidates among elected candidates.

The CPCD records 31 variables common for all elections and additional 13 election-specific variables. We describe the common variables here and refer the readers to the Codebook (see Supplementary Information A) for a description of election-specific variables. Table 3 lists the original names of the common variables retrieved from primary datasets, the CPCD names, and includes labels that describe the variable. Variables can be broadly grouped into three categories: election, candidate, and election results. The first category contains election_year, election_date (first day of the election), and election_type.

The second and largest category of variables includes a candidate’s ID (person_id) and pre-election information, i.e., information voters would know (or could easily infer) before voting. The former is a unique identifier for each candidate created during the merging process, with a structure that reflects the number and types of elections in which a candidate ran. The latter largely adopt variables from the primary datasets, including first name, last name, age, academic titles, place of residence (name and code), ballot position, and party membership and affiliation. We also keep occupation as a string variable in the Czech language.

We created three new variables: birth year, gender, and education. Variable candidate_birthyear was created as the difference between the election year and the age of a candidate announced on the ballot lists. Variable candidate_gender classifies candidates as male or female based on the dictionary of male and female first names from the Ministry of the Interior. If both males and females use the same first name, we identify females based on the ending of their last name and the name of the occupation provided by candidates on the ballot list, as Czech women’s last names and words for occupations have predominantly gender-specific endings. The variable candidate_education builds on academic titles stated on the ballot list. We use a dictionary of academic titles to categorize candidates into six education levels: (1.) no university education; (2.) BA degree; (3.) MA degree; (4.) PhD degree; (5.) associate professor (docent, habilitation); (6.) full professors. Similar categorization has been used in previous research11. Two notes about academic titles are worth mentioning. First, academic titles are self-reported with no formal validation process. Second, Czech voters seem to interpret academic titles (especially medical and law titles) as a sign of a candidate’s expertise and tend to cast more votes for educated candidates, further reinforcing candidates’ interest in stating their academic titles11,19.

The final dataset also contains three variables regarding candidates’ party membership and party affiliation, which come directly from primary datasets. The variable candidate_partymem refers to formal party membership. The variable candidate_partyrun provides the name of the list of candidates running the election. If a single party forms a ticket to run in elections, this variable is the same as the name of the party. However, when parties form a coalition, the name of the list differs from that of allied parties and reflects the nature of a coalition. Sikk and Köker (2019) refer to this variable as electon36. Finally, the variable candidate_partynom signals which party nominated a candidate and corresponds to the endorsing party in the coalition. The dataset contains an abbreviated party name (acronym) and the party’s numerical code for all three party-related variables. The codes come from the list of registered political parties provided by the Ministry of the Interior, which contains long names, short names, and numerical codes for each party. The name and numerical code are identical across all elections if the party is organizationally stable. We provide an unabbreviated name only for candidate_partyrun. If independent candidates run in municipal and Senate elections, then the variables candidate_partyrun and candidate_partynom record a code “independent candidate”. The dataset also contains information on where a candidate lives (candidate_place_code, candidate_place_name). In the case of municipal elections, this variable also shows the city or village where a municipal assembly was elected.

Finally, the variable candidate_validity captures whether a candidate actually ran in an election. Because candidate lists are submitted almost two months before an election, candidates may die, withdraw their candidacy, or be dismissed by the party before the election. Their ballot rank (cand_ranking) is recorded as if they ran for election. However, preference votes are recorded as 0 or N/A. If we restrict the data to candidates who actually ran in elections, the number of unique candidates drops from 841,565 to 838,656 and the number of candidate-election observations falls from 1,716,471 to 1,708,049.

The third category contains post-election variables, i.e., variables regarding the election results. This includes the preference votes received in absolute values (candidate_voteN) and as a percentage of all preference votes given to a candidate’s party (candidate_voteP). In municipal elections, candidate_voteP is given as a percentage of all votes a candidate’s party list received. After preference votes are considered, the candidate’s final ranking is provided (ranking_seat, ranking_subs). Finally, we add the absolute and relative number of votes a candidate’s party received in the constituency (party_voteN, party_voteP).

The Senate election data differ slightly, as the two-round majority system tends to lead to two election rounds. For both rounds, we record the absolute and relative number of votes for candidates and whether a candidate was elected. Two variables, candidate_voteN and candidate_voteP, are recorded only for flexible proportional representation systems (municipal, regional, Chamber of Deputies, European Parliament), while for the Senate we provide four different variables with the same root name, but different suffixes (candidate_voteN_SR1, candidate_voteN_SR2, candidate_voteP_SR1, candidate_voteP_SR2).

Additionally, the dataset contains variables related to the constituency in which the election took place. For municipal elections, this includes the municipality ID (municipality_id), municipality name (municipality_name), and the city district ID (city_district_id). The municipality ID remains the same over time. If a part of a municipality detaches from its original municipality, the newly formed municipality is assigned a new ID, while the original municipality retains its existing ID. For regional elections, the dataset contains the region ID (region_id) and name (region_name). Finally, the constituency for Senate elections is captured by the district number (senate_const_id), while for the Chamber of Deputies, we use chamber_const_id. Note that the electoral region number changed in 2002 due to electoral reform.

Czech Political Donation Dataset

The final dataset contains 57,339 donor-party-year unit observations and 38,472 unique donors. Tables 4 and 5 report the number of unique donors and the total sum of financial and non-financial donations by political party and year, respectively. It also indicates which data is from digitally readable sources and which are extracted from PDF files. For each observation, the dataset records the political party to which the donation was addressed (donation_party), the first name (donor_name), last name (donor_surname), year of birth (donor_birthyear), year of donation (donation_year), amount of total donation (donation_all), amounts of financial (donation_financial) and non-financial (donation_nonfinancial) donations, ID (donor_id) indicating unique donors and person ID (person_id) that links the CPDD and the CPCD. Finally, the dataset also includes information on whether the observation is from digitally readable documents or extracted from PDF files (donation_source). The list of variables is presented in Table 6. Matching the CPDD with the CPCD leads to 18,594 matches, indicating that 32% of the number of donations (and 53% of donations value) were made by candidates.

Technical Validation

This section provides technical validation for both the CPCD and the CPDD datasets. We developed several procedures to ensure data quality and reproducibility of the results. The aim of this section is to describe the logic of the validation and its results. This quality assurance process is largely implemented in R.

Technical validation for CPCD

We implemented three technical validity checks for the CPCD. First, we ensured that the variables contain valid codes, names, and numerical values. Specifically, we verified that the percentage of preference votes fell between 0 and 100, the absolute number of votes was non-negative, and that other variables, including gender, education, age, seat, and birth year, were free of missing or invalid data. We also checked whether the CPCD recorded 0 votes for candidates who eventually did not run in an election. Finally, we compared the sum of the variable seat, an indicator for elected status, to the number of seats filled for each election and each constituency. Counts based on the CPCD shown in Table 2 match exactly the numbers provided by the CZSO.

Second, we compare the CPCD to two publicly available datasets that partly cover Czech political candidates: Comprehensive European Parliament electoral data (COMEPELDA) and the dataset used in the Party People book that studies candidate turnover in elections in Central and Eastern Europe37. We also intended to compare the CPCD to the Constituency-Level Elections Archive (CLEA), but abandoned the plan after we found that the CLEA dataset was flawed and inconsistent with the primary and the only authoritative dataset provided by the CZSO.

COMEPELDA consolidates information on European Parliament elections into one source. It provides information on formal electoral rules as well as national-level and district-level election results for parties and individual politicians (including full candidate lists)3. In the case of parties covered by COMEPELDA, the number of candidates running on their party lists is the same. In addition, the comparison of individual candidates, the number of preferential votes, and elected MEPs is the same in both datasets.

We utilize the dataset used in the Party People book to validate our matching of candidates across elections. Specifically, we replicate the Czech parties’ weighted candidate novelty (WCN) in two consecutive elections to the Chamber of Deputies for the period from 1998 to 2013 from Sikk and Köker36. Candidate novelty measures the share of candidates who did not run in any previous election, which is then weighted by the candidates’ list position and the parties’ vote share, to calculate WCN. Our measure of WCN strongly correlates (r > 0.9) with the WCN reported by Sikk and Köker36; see Tables S2–S6 in Supplementary Information B.

Third, we identified recently published academic articles on females among elected representatives in the Czech Republic8,38 and compared the numbers to those we derived using the CPCD. The variable indicating female candidates in the CPCD was created based on the names of the candidates (see section Data records), so the comparison of female shares provides further validation of the data transformations. We present the share of females among elected representatives for all elections in the last column of Table 2. The first study compared, by Maškarinec8, graphically presents the share of women among elected representatives for the Chamber of Deputies, the European Parliament, and regional and municipal assemblies. The graphical comparison of our statistics and the figure from Maškarinec8 suggests that there are no discrepancies in the numbers of female elected officials between his study and our data. The second study, by Voda (2022), provides exact numbers for seven municipal elections. We record the same numbers for three elections (2010, 2014, and 2018) and differ by 0.1 percentage points in three other elections (1994, 1998, and 2006). In the 2002 election, the difference was larger, as CPCD statistics yield 22.6% of female elected candidates, while the study by Voda (2022) says 27.1%. As CPCD’s 22.6% corresponds to the same figure presented in the study by Maškarinec8, we believe the CPCD yields more credible statistics.

Technical validation for CPDD

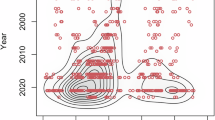

To validate the CPDD dataset, we used donors’ dates of birth. Because public authorities lack the means to verify the accuracy and correctness of the submitted list of donors, there could be some concern that reported donors are made up. Personal donor information, such as date of birth, would be the primary suspect, as this piece of information is the most challenging to verify. We build on psychological literature that argues that people have difficulty generating random digits to test for potentially made-up dates of birth, similar to what is known in the literature as election forensics to detect fraud in election results39,40.

We test that day-in-month donors’ dates of birth are distributed with an equal frequency. We collapsed donors for a given party over the period studied, so that each donor is counted once regardless of the value or the number of donations made. Table 7 shows Pearson χ2 statistics, the corresponding p-value, and the most frequent day for each political party considered. The p-value is (weakly) larger than a 0.05 significance level for each political party. However, KSČM (p-value of 0.063) and Přísaha (p-value of 0.050) are on the margin of statistical significance. Figures S1, S2, and S3 in Supplementary Information C show the distance from the average number of donors born on a given day by a political party. Note that we restrict the sample to days between the 1st and 28th, as subsequent days are predicted to be represented less in a random sample of dates. Similarly, the argument of random allocation of day-in-month dates does not generalize to months, as births are not randomly distributed over a year.

Compared to other information provided in the dataset, dates of births are the least verifiable from public sources. Therefore, we believe that the lack of evidence of manipulating birth dates is promising evidence that the other information was not manipulated either.

Code availability

The CPCD and CPDD are publicly available: https://doi.org/10.14473/CSDA/MDZC3F34. The code to replicate the construction of the final datasets introduced in this paper and the analysis presented is available through the OSF repository https://osf.io/rakjz/35. All files use UTF-8 encoding.

References

Folke, O., Persson, T. & Rickne, J. The Primary Effect: Preference Votes and Political Promotions. American Political Science Review 110, 559–578 (2016).

Fiva, J. H., Sørensen, R. J. & Vøllo, R. Local Candidate Dataset https://www.jon.fiva.no/docs/FivaSorensenVollo2024.pdf (2024).

Däubler, T., Chiru, M. & Hermansen, S. S. Introducing COMEPELDA: Comprehensive European Parliament Electoral Data Covering Rules, Parties and Candidates. European Union Politics 23, 351–371 (2022).

André, A., Depauw, S., Shugart, M. S. & Chytilek, R. Party Nomination Strategies in Flexible-list Systems: Do Preference Votes Matter? Party Politics 23, 589–600 (2017).

Linek, L. & Pecháček, Š. Low Membership in Czech Political Parties: Party Strategy or Structural Determinants? Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 23, 259–275 (2007).

Hájek, L. Whose Skin is in the Game? Party Candidates in the Czech Republic. East European Politics 35, 372–394 (2019).

Kostelecký, T., Bernard, J., Mansfeldová, Z. & Mikešová, R. From an Alternative To a Dominant Form of Local Political Actors? Independent Candidates in the Czech Local Elections in 2010-2018. Local Government Studies 0, 1–23 (2023).

Maškarinec, P. Women and Local Politics: Determinants of Women’s Emergence and Success in Elections to Czech Town Councils, 1998–2018. Urban Affairs Review 58, 356–387 (2022).

Stegmaier, M., Tosun, J. & Vlachova, K. Women’s Parliamentary Representation in the Czech Republic: Does Preference Voting Matter? East European Politics & Societies 28, 187–204 (2014).

Hájek, L. The effect of Multiple-office Holding on the Parliamentary Activity of MPs in the Czech Republic. The Journal of Legislative Studies 23, 484–507 (2017).

Jurajda, Š. & Münich, D. Candidate Ballot Information and Election Outcomes: The Czech Case. Post-Soviet Affairs 31, 448–469 (2015).

Coufalová, L., Mikula, Š. & Ševčík, M. Homophily in Voting Behavior: Evidence from Preferential Voting. Kyklos 76, 281–300 (2023).

Coufalová, L. & Mikula, Š. The Grass Is Not Greener on the Other Side: The Role of Attention in Voting Behavior. Public Choice 194, 205–223 (2023).

Marcinkiewicz, K. & Stegmaier, M. Ballot Position Effects Under Compulsory and Optional Preferential-List PR Electoral Systems. Political Behavior 37, 465–486 (2015).

Kouba, K. & Lysek, J. The Return of Silent Elections: Democracy, Uncontested Elections and Citizen Participation in Czechia. Democratization 30, 1527–1551 (2023).

Ryšavý, D. & Bernard, J. Size and Local Democracy: The Case of Czech Municipal Representatives. Local Government Studies 39, 833–852 (2013).

Škvrňák, M. No Coalition Is an Island: How Pre-Electoral Coalitions at the National-Level Shape Local Elections. Local Government Studies 0, 1–28, https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2024.2425751 (2024).

Škvrňák, M. You’ll Never Rule Alone: How Football Clubs and Party Membership Affect Coalition Formation. Local Government Studies 47, 312–330, https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2020.1787167 (2021).

Svitáková, K. & Šoltés, M. Ranking of Candidates on Slates: Evidence from 20,000 Electoral Slates. Party Politics 30, 465–478 (2024).

Titl, V. & Geys, B. Political Donations and the Allocation of Public Procurement Contracts. European Economic Review 111, 443–458 (2019).

Titl, V., De Witte, K. & Geys, B. Political Donations, Public Procurement and Government Efficiency. World Development 148, 105666 (2021).

Baránek, B. & Titl, V. The Cost of Favoritism in Public Procurement. The Journal of Law and Economics 67, 445–477 (2024).

Kuliomina, J. Do Personal Characteristics of Councilors Affect Municipal Budget Allocation? European Journal of Political Economy 70, 102034 (2021).

Palguta, J. Political Representation and Public Contracting: Evidence from Municipal Legislatures. European Economic Review 118, 411–431 (2019).

Palguta, J. & Pertold, F. Political Salaries, Electoral Selection and the Incumbency Advantage: Evidence from a Wage Reform. Journal of Comparative Economics 49, 1020–1047 (2021).

Däubler, T., Christensen, L. & Linek, L. Parliamentary Activity, Re-Selection and the Personal Vote. Evidence from Flexible-List Systems. Parliamentary Affairs 71, 930–949 (2018).

Marcinkiewicz, K. & Stegmaier, M. Speaking Up to Stay in Parliament: The Electoral Importance of Speeches and Other Parliamentary Activities. The Journal of Legislative Studies 25, 576–596 (2019).

Smrek, M. Do Female Legislators Benefit from Incumbency Advantage? Incumbent Renomination in a Flexible-List PR System. Electoral Studies 66, 102189 (2020).

Smrek, M. Mavericks or Loyalists? Popular Ballot Jumpers and Party Discipline in the Flexible-List PR Context. Political Research Quarterly 76, 323–336 (2023).

Czech Statistical Office. Population of Municipalities - as at 1 January 2024 https://csu.gov.cz/produkty/population-of-municipalities-qexb0dqr2d (2024).

Ladner, A., Keuffer, N. & Bastianen, A. Local Autonomy Around the World: The Updated and Extended Local Autonomy Index (LAI 2.0). Regional & Federal Studies 1–23 (2023).

Hooghe, L. et al. Measuring Regional Authority: A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance. Transformations in Governance (Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom; New York, 2016), first edition.

Lipcean, S. Direct Public Funding of Political Parties: Between Proxy Measures and Hard Data. Party Politics 28, 1041–1057 (2022).

Linek, L., Škvrňák, M., Šoltés, M. & Titl, V. Czech olitical Candidate and Donation Datasets. CSDA Dataverse, https://doi.org/10.14473/CSDA/MDZC3F (2024).

Linek, L., Škvrňák, M., Šoltés, M. & Titl, V. Czech Political Candidate and Donation Datasets: Data and Scripts. OSF, https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/RAKJZ (2024).

Sikk, A. & Köker, P. Party Novelty and Congruence: A New Approach to Measuring Party Change and Volatility. Party Politics 25, 759–770 (2019).

Sikk, A. & Köker, P. Party People: Candidates and Party Evolution (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2023).

Voda, P. Czech Republic. In Gendźwiłł, A., Kjaer, U. & Steyvers, K. (eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Local Elections and Voting in Europe, Routledge International Handbooks, 271–281 (Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, London; New York, 2022).

Beber, B. & Scacco, A. What the Numbers Say: A Digit-Based Test for Election Fraud. Political analysis 20, 211–234 (2012).

Nickerson, R. S. The Production and Perception of Randomness. Psychological review 109, 330 (2002).

Acknowledgements

The work of Lukáš Linek and Michael Škvrňák was supported by the NPO “Systemic Risk Institute” no. LX22NPO5101, funded by European Union - Next Generation EU (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, NPO: EXCELES). Vítězslav Titl gratefully acknowledges financial support from the European Research Council (project ‘DemoTrans’ – 101059288). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the granting authority. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. We are grateful to Alice Navrátilová for her assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.L., M.Šo., M.Šk., V.T. conceived, designed, and performed the study; contributed to and wrote the paper; and approved the final manuscript. M.Šo., V.T. prepared CPDD. M.Šk. prepared CPCD.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Linek, L., Škvrňák, M., Šoltés, M. et al. Czech political candidate and donation datasets. Sci Data 12, 302 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04617-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04617-5

This article is cited by

-

The Latin American Legislators Dataset

Scientific Data (2025)