Abstract

Global warming and urbanization serve as critical research themes in fine-scale climate studies, particularly in developed cities. This study aims to provide a high spatiotemporal resolution dataset of near-surface air temperatures for densely developed urban areas. The dataset comprises daily maximum, minimum, and mean temperatures for the summer months (June to August) from 2019 to 2023, at a spatial resolution of 100 m, across the Jiangbei climate zone in China. We applied the Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory (ConvLSTM) deep learning model with multi-source data, including ERA5 temperature data, topography, landcover and vegetation fraction cover. Model evaluation indicates high accuracy, with mean absolute errors (MAE) ranging from 0.564 to 0.784 °C, root mean square errors (RMSE) from 0.733 to 1.027 °C, and coefficients of determination (R2) from 0.892 to 0.943. Our dataset is distinguished by the 100 m spatial resolution and the inclusion of recent summer data from 2023 at a daily scale. This work is valuable for urban or inner-urban climate studies on heatwave mitigation policies and adaptation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Global warming has increased the frequency of extreme heat events1. Accelerating urbanization exacerbates the negative impacts of these extreme events on urban environments, human health, and socio-economic activities2,3,4. In densely populated and socio-economically advanced regions, the complex geographical environment and intense human activities heighten the severity of extreme heat, particularly in summer5,6. Thus, conducting urban heat studies, especially recent extreme high-temperature events, has become more critical in these regions.

Near-surface air temperature at 2 meters above ground (2m-air temperature) is essential for urban heat research. While its continuous spatial distribution is crucial for climate studies, temperature records are typically obtained from spatially discrete meteorological stations. Previous researchers have used Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) or Kriging interpolation7,8 to generate gridded temperature data. However, unevenly distributed stations9 often fail to capture fine-scale variations in complex environments, particularly in urban areas with low station density. Satellite-derived land surface temperature (LST) enables to capture urban heat distribution at higher spatial resolution, and has been widely applied to heatwave studies10,11. LST provides more accurate and finer temperature distribution than interpolated data12,13, and correlates strongly with air temperature14,15. However, air temperature and LST differ significantly in terms of physical processes, fine-scale spatiotemporal distributions, feedback times, and temperature values15,16,17. As a result, high-resolution air temperature data remains an indispensable component for urban climate studies.

To address the lack of high-resolution temperature data, researchers have conducted spatial downscaling based on reanalysis data such as ERA5, JRA-55, and MERRA218,19,20 or simulation data from General Circulation Models (GCMs)21,22, leveraging their broad coverage and high temporal resolution. Downscaling methods include dynamical, statistical, and hybrid approaches23. Statistical downscaling has gained wider usage due to the ease of understanding and implementation, particularly the nonlinear approaches represented by machine learning methods. These algorithms predict temperature by modeling relationships between high-resolution spatial data (eg. DEM, LULC, or LST), and station-observed temperatures. Examples include Deep Belief Networks24, ExtraTrees25, and Cubist26, and ensembles of methods like boosted regression trees, random forests, neural networks, multivariate adaptive regression splines, support vector machines, and the generalized additive model27. However, these approaches often neglect the spatial and temporal correlations between temperature and the environment, limiting their effectiveness in urban areas with complex spatiotemporal dynamics.

Considering the spatiotemporal dependencies in temperature downscaling, the Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory (ConvLSTM) network28 has emerged as a promising deep learning model. ConvLSTM captures both spatial and temporal correlations, which makes it valuable for meteorological applications. Existing research has shown that ConvLSTM performs well in forecasting precipitation28,29, temperature30, wind speed31, and cloud cover32. Typically, ConvLSTM is used for prediction tasks focusing on final-step outputs. However, obtaining outputs at each time step, rather than only at the final step, enables the production of continuous data. When high-resolution spatial data are used as model inputs, ConvLSTM demonstrates potential in generating temporally continuous and fine-grained urban temperature data.

Extreme high temperatures in summer have become more frequent in recent years, significantly impacting densely populated and socio-economic active areas33. This study focuses on the summers (June to August) from 2019 to 2023 in Jiangbei climate zone of China, where the largest urban agglomeration of Yangtze River Delta is located. To address the lack of high- resolution gridded temperature data, we aim to: 1)use the ConvLSTM algorithm with inputs from ERA5, ERA5-Land, DEM, land use (LULC)34, and fractional vegetation cover (FVC) data to generate daily maximum(Tmax), minimum(Tmin), and mean(Tmean) temperature data at 100-meter spatial resolution; 2) conduct a comprehensive accuracy analysis, including spatiotemporal evaluations and comparisons with other datasets, to validate the feasibility of applying ConvLSTM algorithm for temperature downscaling. The dataset, covering five recent years of temperature data, demonstrates good reliability and serves as a valuable resource for urban heat monitoring, mitigation, and urban planning.

Methods

Study area

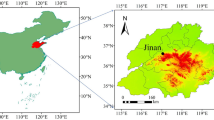

The study area is defined as the Jiangbei Climate Zone, a secondary climatic zone in the climate classification released by the China Meteorological Administration. This area is located in the North Subtropical Zone, spanning longitudes from 110.22°E to 121.91°E and latitudes from 27.20°N to 34.10°N in the WGS84 geographic coordinate system. The eastern part of the study area encompasses the economically and densely populated Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration, while the western part covers areas in Hunan and Hubei provinces. These regions frequently experience extreme high-temperature events during the summer, leading to severe socioeconomic losses and environmental damage. These developed cities are characterized by high population density and significant surface heterogeneity. The pronounced urban-rural differences contribute to complex, locally specific temperature variations at fine spatial scales. Thus, studying the Jiangbei climate zone and selecting the summer period for analysis offers significant representativeness. The area contains 276 meteorological stations providing temperature records. Since these stations do not cover water bodies, and given the distinct thermal properties of land and water, a mask was applied to exclude water body temperatures from the final dataset. A schematic of the study area is shown in Fig. 1.

Data sources and processing

We utilized several datasets for temperature downscaling. The primary datasets are hourly temperature data from the ERA5 and ERA5-land reanalysis products35,36. Auxiliary datasets include the SRTM90 Digital Elevation Model (DEM), CLCD land use/land cover (LULC)34, Vegetation Fraction Cover (FVC) derived from Sentinel-2 imagery. Meteorological station data were obtained from the National-level Ground Meteorological Station Basic Meteorological Element Daily Dataset of China (V3.0). Station data served as labels for model training and testing, while the climate zoning vector data assisted in delineating the study area.

ERA5 and ERA5-land reanalysis products

ERA5-land provides hourly temperature at a higher spatial resolution of 0.1° but only for land areas, resulting in gaps at land-water interfaces. To address this problem, we used seamless ERA5 data at 0.25° resolution to fill gaps in ERA5-Land. As the study area is located within China, the ERA5-hourly (UTC) and ERA5-land-hourly (UTC) data were converted to the China time zone (UTC + 8). ERA5 data were resampled to a resolution of 0.1° using bilinear interpolation and merged with ERA5-land to create seamless hourly temperature. Daily maximum (Tmax), minimum (Tmin), and mean (Tmean) temperatures were subsequently calculated from the hourly data.

Auxiliary datasets

Temperature is closely correlated with elevation, as higher altitudes tend to have lower temperatures. DEM provides essential topographic information, which directly influence temperature patterns37. Different land use types also affect temperature variations25,38,39. Increasing human activity amplifies the impact of impervious surfaces on temperature. However, LULC data can be less effective in regions with homogenous land cover25, such as mountainous areas, where similar pixel codes may fail to capture temperature variations. Although the selected LULC data meet the study’s temporal and spatial resolution requirements, the limited number of categories (shown in Table 1) results in similar challenges. Moreover, in urban areas, high land use heterogeneity and the target resolution of 100 m still poses a risk of accuracy loss, especially with dispersed urban green spaces. Considering the above two reasons, we planned to incorporate NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) and FVC (Fractional Vegetation Cover) data to supplement LULC information. Therefore, Sentinel-2 imagery is chosen to calculate NDVI due to its high revisit frequency and 10 m spatial resolution, and then FVC was estimated based on NDVI40 (Eq.(1)). Where the value at the 5% in the NDVI pixel percentage statistics is defined as \({{NDVI}}_{\min }\), and the value at the 95% is defined as \({{NDVI}}_{\max }\).

Datasets for comparison

To evaluate the performance of the ConvLSTM downscaling dataset(denoted as CMData), two additional datasets are selected for comparison: (1) daily temperature data for June to August from 2019 to 2022 (WData)41, and (2) monthly temperature data for June to August from 2019 to 2023 (TData)42,43,44,45. To ensure consistency in the temporal scale, both CMData and the station temperature data are aggregated to a monthly scale for comparison with TData.

ConvLSTM model structures and parameters

Given the strong temporal correlation of temperatures and to emphasize the influence of the surrounding environment on the central location, we employed the ConvLSTM algorithm28 as the estimation model. The ConvLSTM algorithm, an improvement of the LSTM algorithm, incorporates spatial features of images. This model better captures spatiotemporal correlations compared to the standard LSTM algorithm or many other machine learning models. ConvLSTM extends fully connected LSTM (FC-LSTM) by embedding convolutional structures in both the input-to-state and state-to-state transitions. In the ConvLSTM algorithm, the gating mechanisms (input gate, forget gate, and output gate) are implemented using convolutional operators. In this study, to align with the station-based labels, we added a convolutional layer as the final step in our model to produce a single output value. The primary equations are in Eqs. (2–6). Where ∘ stands for Hadamard product, * stands for convolution operator.

To balance the computational efficiency and model accuracy, we chose the scheme with the smallest number of weighting parameters but also with best results. Therefore, the network used in this study consists of three ConvLSTM layers with 128, 64, and 64 hidden units, respectively. A convolutional layer is applied at the end to produce the outputs for Tmax, Tmin, and Tmean. The convolutional kernel size is set to 5 × 5. Through optimization and testing, we achieved a balance between model accuracy and the risk of overfitting. Among other parameters, the batch size is set to 32, and the number of training epochs is set to 50.

Downscaling workflow

This study is based on two hypotheses: (1) The surrounding environment influences the temperature at the central location. Accordingly, we selected the pixels corresponding to meteorological station locations and their surrounding 5 × 5 image windows as data batches. (2) The relationship between temperature and environmental factors remains relatively stable over a few years. Although global warming is a serious long-term phenomenon1, short-term fluctuations exist and the linear trends are not evident over only several years. This hypothesis ensures the feasibility of sharing the same model within the research period (five years). Additionally, by focusing the time frame on summer, the large-scale temperature fluctuations are somewhat mitigated.

In this study, we first processed the daily temperature data calculated from ERA5 and ERA5-land, DEM, LULC, and FVC data using the bilinear interpolation to achieve the 0.001° (approximately 100 m) spatial resolution. Using the processed data as ConvLSTM model inputs, we generated daily Tmax, Tmin and Tmean data at a spatial resolution of 100 m. We then conducted a temporal and spatial accuracy assessments with calculating MAE, RMSE and R2 metrics, along with comparing to other datasets. Moreover, we analyzed the channel importance of the chosen factors as the input data and discussed the application value of our downscaled dataset. The specific methodological workflow, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Training process

After bilinear interpolation to primary multi-datasets, we applied Z-score standardization to Tmax, Tmin, Tmean, and DEM, while FVC, NDVI and LULC were used in their raw forms. Since NDVI and FVC are strongly correlated, we tested three scenarios—using NDVI, FVC, or both—and found that using only FVC resulted in smaller training losses. Thus, FVC was selected with DEM and LULC as the final auxiliary inputs. In the standardized images, we extracted image windows corresponding to meteorological stations and stacked them into a six-dimensional array: ID, Year, Time_Step, Channel, Height, Width. Here, ID represents different stations, Year represents research years (2019–2023), Time_Step represents days (June to August, 92 days), Channel represents input variables (Tmax, Tmin, Tmean, DEM, FVC, LULC), and Height and Width represent the window dimensions (both 5). After randomly selecting training and testing stations, we merged the ID and Year dimensions into the Batch dimension, resulting in a five-dimensional input array: Batch_Size, Time_Step, Channel, Height, Width. The model’s loss function is Mean Squared Error (MSE). Initially, the loss was defined as the mean MSE of Tmax, Tmin, and Tmean. After testing, we found that MSE for Tmax and Tmin was higher than for Tmean. Thus, we adjusted the loss function to a weighted sum of the MSEs, with weights of 0.4 for Tmax and Tmin, and 0.2 for Tmean.

Results validation

We evaluated the final results using Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and coefficients of determination (R²) metrics, calculated as Eqs. (7–9). Where \({S}_{i}\) denotes the predicted value, and \({O}_{i}\) denotes the station observed value. Additionally, WData41 and TData45 were selected for comparisons with the results produced by our study. We clipped CMData, WData and TData in one coastal city (Shanghai) and one inland city (Changsha), to compare the station-based accuracy and temperature distributions at different spatial scales. The boundaries of these two city centers were obtained from the standard city center maps at National Platform for Common Geospatial Information Services (https://www.tianditu.gov.cn/).

Model inference

Initial model training and validation were conducted using station-based data. For pixel-level temperature inference, we employed a sliding window approach. First, input data were standardized using the same mean and standard deviation as the training data: for Tmax, 30.950 and 3.285; for Tmin, 24.081 and 2.709; for Tmean, 27.303 and 2.723; and for DEM, 69.769 and 138.189. A 5 × 5 window surrounding each target pixel was then extracted as input for inference, and the model was applied to obtain Tmax, Tmin, and Tmean.

Data Records

All the temperature data produced in this study are available in National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center (TPDC) at https://doi.org/10.11888/Atmos.tpdc.302013 or https://cstr.cn/18406.11.Atmos.tpdc.30201346. Users can download the dataset through ftp. Data associated with this work include temperature of meteorological station, climate zoning vector of China, ERA5, ERA5-land, SRTM 90 DEM, Sentinel-2 imagery and LULC for producing the downscaling temperature dataset, two downscaling datasets for comparing the accuracy of our downscaling results. The information for all datasets is summarized in Table 2.

Technical Validation

Overall performance of the ConvLSTM model

The model’s performance was assessed using the MAE, RMSE and R² metrics, comparing station observations with predicted values. As shown in Table 3, the accuracy metrics for training and testing datasets are similar, indicating that the model do not overfit and demonstrates good generalizability. Figure 3 shows that, the overall accuracy of Tmean exhibits higher than Tmax and Tmin. The MAE and RMSE for Tmax are 0.784 °C and 1.027 °C, respectively, representing the largest inaccuracies among the three variables. The MAE and RMSE for Tmin are 0.696 °C and 0.908 °C, indicating moderate inaccuracies, and for Tmean are 0.564 °C and 0.733 °C, showing the smallest inaccuracies. The R² values indicate that the predicted values align more closely with observed values for Tmean (0.943) and Tmax (0.929) compared to Tmin (0.892). Overall, the model demonstrates good applicability and low prediction errors.

Temporal evaluation of model performance

Figure 4 presents boxplots of the absolute differences (ΔTmax, ΔTmin, ΔTmean) between observed values and predicted values for Tmax, Tmin, and Tmean. Figure 4(a) and Table 4 show the MAE, RMSE, and R² results at the monthly scale, indicating that the prediction accuracy is higher in August than in June and July. Figure 4(a) also show that, despite a noticeable outlier, the interquartile range (IQR) for August is smaller than for June and July. This phenomenon may be attributed to the memory characteristic of the LSTM algorithm. Figure 4(b) and Table 5 show the results at the annual scale (June to August for each year). Figure 4(b) shows a larger IQR for 2020 and 2023, particularly in 2023, where predicted values tend to be higher than observed values. The model performs better in predicting Tmax for 2019 and 2022, with slightly higher accuracy in 2022 despite an outlier in 2019. For Tmin and Tmean prediction, the model performs well in 2020 and 2021, with Tmin’ s MAE below 0.7 °C and RMSE below 1 °C, Tmean’s MAE below 0.56 °C and RMSE below 0.72 °C. Overall, the model shows higher accuracy in August, while annual accuracy varies without a consistent pattern.

Spatial evaluation of model performance

Figure 5 presents the overall MAE and R² results for each station. Figure 5(a,d) show that most stations have high accuracy for Tmax, with MAE below 1 °C and R² above 0.9. However, station 58317 (Yuexi, located in Anhui Province) exhibits a significant Tmax anomaly, with an MAE of 2.34 °C and an R² of only 0.40. This anomaly explains the lower accuracy of Tmax compared to Tmin and Tmean. Figure 5(b,e) show that the accuracy of Tmin is generally high, with MAE below 1 °C and R² above 0.8. The station with the lowest accuracy for Tmin is 58514 (Xingzi, located in Jiangxi Province), with an MAE of 1.23 °C and an R² of 0.63. Figure 5(c,f) indicate that Tmean predictions are highly accurate, with most stations showing MAE below 0.8 °C and R² above 0.9. Station 58317 has the lowest accuracy, with an MAE of 1.1 °C and an R² of 0.69. In summary, the spatial evaluation results indicate that predictions achieve high accuracy at most stations, while the lower accuracy at specific stations impacts the prediction performance of the Tmax, Tmin, and Tmean variables.

Auxiliary data evaluation of model performance

Figure 6 shows station attributes extracted from the LULC, DEM, and FVC datasets, along with corresponding MAE values. Figure 6(a) shows that stations in the forest exhibit the lowest accuracy, with MAE of 1.00 °C for Tmax, 0.76 °C for Tmin, and 0.68 °C for Tmean. Figure 6(b) shows that prediction accuracy generally decreases with increasing DEM. Stations with a DEM range between 335.3–759.1 meters exhibit significantly lower accuracy, with MAE values of 1.24 °C for Tmax, 0.85 °C for Tmin, and 0.78 °C for Tmean. Figure 6(c) shows that the accuracy remains relatively stable with changes in FVC. However, stations in high vegetation cover (FVC > 0.75) areas show a decrease in prediction accuracy, with MAE values of 0.81 °C for Tmax, 0.71 °C for Tmin, and 0.58 °C for Tmean. In the spatial evaluation analysis above, stations 58317 and 58514 exhibit notably lower accuracy. Station 58317 performs poorly in Tmax and Tmean predictions. Although Tmin accuracy is better than at station 58514, the MAE remains the third highest (1.08 °C). Located in a forest area with an elevation of 427 meters and FVC of 0.90, this station contributes to the higher MAE in forest areas, at elevations of 335.3–759.1 meters, and with FVC of 0.75–0.98. Station 58514 shows poorer performance in Tmin prediction but better in Tmax and Tmean. The land use type at this station is cropland, with an elevation of 41 meters and an FVC of 0.81. This combination of factors exacerbates the lower accuracy in high FVC areas but does not significantly influence cropland or lower elevation stations. Overall, prediction accuracy is higher in non-forested, lower elevation, and moderately vegetated areas, while forested, higher elevation, and densely vegetated areas exhibit lower accuracy.

Comparing with other datasets

The daily-scale WData and the monthly-scale TData were selected to compare with our downscaled dataset (CMData). Figure 7 compares the predictions extracted from the three datasets at the stations within the study area. For the overlapping period, WData shows higher accuracy for Tmax, Tmin, and Tmean compared to CMData, with MAE and RMSE mostly below 0.5 °C, except for Tmax RMSE is about 0.6 °C. CMData shows both MAE and RMSE exceeding 0.5 °C, with Tmax and Tmin’s RMSE approaching 1 °C. Despite WData’s higher accuracy, CMData offers advantages in spatial resolution (100 m vs. 1 km), includes more recent data (2023), and provides a more detailed temperature variations within small areas, which is more reasonable of station’s representative local area. For comparison with TData, observational data and CMData were aggregated to a monthly scal. CMData shows far superior accuracy, with TData’s MAE and RMSE ranging from 2 °C to 4 °C, while CMData’s metrics are mostly below 1 °C, except for Tmax RMSE slightly above 1 °C. Thus, CMData demonstrates higher accuracy and finer spatiotemporal resolution than TData

We further compared the spatial distribution of CMData and WData at urban and intra-urban scales, where notable differences were observed. Mean summer temperatures for the overlapping period (2019 to 2022) were calculated for both datasets. Figures 8, 9 show the spatial distributions for Shanghai (coastal) and Changsha (inland), respectively. Both datasets show consistent temperature distributions, but CMData provides clearer boundaries, particularly at the finer scale of city centers. CMData shows a more distinct variation and highlight the urban heat island effect. In Shanghai (Fig. 8), CMData exhibits a smoother, more consistent temperature pattern, while WData shows significant local variation, particularly at the low-temperature coastal region. Although CMData does not capture this coastal feature, it still reflects a decreasing temperature trend toward the ocean. In Changsha (Fig. 9), both datasets show smooth spatial variations, but WData’s lower resolution results in blurred temperature images, failing to capture local variations. Thus, CMData more effectively captures temperature variations in urban and central urban areas.

Spatial distribution at different temporal scales

Figures 10, 11 illustrate the total and annual mean aggregation of daily-scale images, and line plots in Fig. 10 presents the daily averages for 2019–2023. Both figures reveal that high-altitude regions (higher DEM values) exhibit significantly lower temperatures than low-altitude areas. Furthermore, northern regions experience lower temperatures than southern regions, and coastal areas display lower temperatures than inland regions, consistent with established geographical patterns. In Fig. 10, Tmax ranges from 18.63 °C to 34.44 °C, Tmin from 13.40 °C to 26.42 °C, and Tmean from 15.90 °C to 29.65 °C. On a daily scale, these variables exhibit a slight trend of increasing followed by decreasing temperatures, with the highest temperatures occurring between mid-July and early August. Temperature fluctuations are evident due to weather disturbances. Figure 11 highlights the interannual variations in Tmax, Tmin, and Tmean, revealing a gradual increase in summer temperatures from 2019 to 2022. In 2022, Tmax reached its highest range of 19.48 °C–36.90 °C, Tmin reached of 14.17 °C–27.73 °C, and Tmean reached of 13.70 °C–31.38 °C. In 2023, however, the temperature ranges for all three variables decreased, approaching the values in 2020. This pattern matches the results from the line plots in Fig. 10 and aligns with objective observations.

Daily spatial distribution at different spatial scales

Given the warming trend in mid-July, we selected the image from July 15, 2023, to examine temperature distributions across different spatial scales. Figure 12 depicts the daily Tmax, Tmin, and Tmean at three spatial scales: larger scale (Jiangbei Climate Zone), medium scale (Shanghai city), and smaller scale (central urban area of Shanghai). The temperature distribution map of Jiangbei Climate Zone confirms that higher-altitude regions exhibit lower temperatures than lower-altitude areas. However, eastern coastal regions do not show lower temperatures than inland areas, possibly due to weather disturbances and the urban heat island effect. Specifically, the eastern coastal region, situated at the core of the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration, features extensive impervious surfaces in Shanghai and northern Zhejiang Province. This anthropogenic surface change intensifies high-temperature phenomena in densely urbanized areas. The urban heat island effect is particularly prominent in the temperature distribution map of Shanghai, where the city center records significantly higher temperatures than surrounding areas. In the central urban area of Shanghai, a high-temperature zone for Tmax is evident in the southwest, while the eastern region exhibits a high-temperature zone for Tmin. Both the southwest and eastern areas show higher Tmean temperatures, while the northwest region remains relatively cooler.

Importance analysis of model input data

ERA5 and ERA5-land temperatures, DEM, FVC, and LULC data were utilized as model inputs. We calculated the importance score for each factor, defined as the percentage change in the total loss function when a specific factor is excluded. The results (Table 6) indicate that ERA5 temperatures, as the primary data, holds a significantly higher importance score. The ranking of importance is Tmean > Tmin > Tmax, which aligns with the model’s prediction accuracy trend of Tmean > Tmin > Tmax. Among auxiliary inputs, the ranking is DEM > LULC > FVC. Figures 10, 11 also underscore DEM’s critical role in shaping temperature predictions, while LULC contributes approximately 4% to model performance. Figure 6 reveals that LULC classes at the stations are limited to three types (cropland, forest, and impervious), limiting the training data diversity and introducing inaccuracy. The importance score of FVC is only 0.89%, possibly due to its generalized nature and lack of a clear quantitative correlation with temperature. Moreover, FVC data used in this study were derived from Sentinel-2 imagery. To make sure of completeness of the whole research area, only one image per year was available within the study period, limiting its model contribution.

Previous studies on deep-learning based temperature downscaling vary in choice of auxiliary data. Some researchers employed fewer inputs, for instance, only DEM and LCZ (Local Climate Zone)25. Some scholars fitted the relationship between LST and temperature, noting that adding other data as input did not significantly improve the accuracy26. Conversely, some research incorporated more comprehensive inputs, for example, the meteorological variables, remote sensing data, geographic parameters, vegetation and soil parameters, population, and road density24,41. These research did not provide specific measurements of the importance of each input factor, thus making it difficult to determine the factor contribution. The accuracy results from some research which uses more input factors are relatively higher than our downscaled data (See Section ‘Comparing with other datasets’). In this study, we employed DEM, LULC, and NDVI due to the balance between efficiency and accuracy, and we validated the feasibility of high-precision temperature predictions with limited data inputs.

Uncertainty of downscaling results

We used the ConvlSTM model to downscale the temperature data from 0.1°~0.25°(ERA5-land and ERA5) to 100 m (0.001°). We base a fundamental assumption present in all statistical and machine learning downscaling methods that low- and high-resolution variables show consistent and quantifiable relationships which will remain valid in the future47. This assumption, alongside the datasets and methods, introduces uncertainties into the results.

In terms of datasets, the LULC data (CLCD)34 used in this study met the requirements for the time range and spatial resolution The data is updated annually, ensuring sustainability for ongoing research. However, the data includes a limited number of land use types, hindering deep learning model performance and increasing uncertainty. FVC data used in this study was calculate using an empirical equation with the median composite of NDVI obtained from Sentinel-2 spectral images. Despite Sentinel-2’s relatively high revisit frequency, some tiles still have missing pixels due to high cloud cover. The median composite produced more stable NDVI results, however, relying on only one image per quarter may not provide sufficient information. Both of these factors contribute to uncertainty in the downscaling results.

In terms of methodology, we employed the ConvLSTM model for temperature downscaling. The ConvLSTM model was originally used for precipitation forecasting, meaning that previous results predict future outcomes. In this study, the model generated inference results for each time step. The outputs for earlier time steps likely exhibited higher uncertainty than those for later time steps. To mitigate uncertainties, we constrained the study to a five-year summer period within a single climate zone, limiting temperature variability despite weather influences. Additionally, although LULC data has fewer land use types, FVC data provided valuable supplementary information, especially for vegetation-covered surfaces. To reduce the impact of high cloud cover on FVC, we extended the time window before and after the June-August period by 15 days, to obtain more complete results. While the downscaled results for later time steps show higher accuracy compared to earlier time steps, the results for earlier periods were still reasonable. The spatiotemporal analysis above also indicates that our temperature results align with objective patterns.

Limitations and future work

The limitations of our dataset primarily lie in the spatiotemporal range. First, the dataset covers only five years of summer temperature data. Although we have obtained the recent data for 2023, the time series remains relatively short. This limitation arises mainly from the auxiliary data of LULC required for model inputs. Second, the dataset is confined to the Jiangbei climate zone in China. This region was chosen as a typical study area due to its concentration of economically developed, densely populated cities. The current dataset can provide recent fine-scale temperature data in typical regions for urban climate studies, while extending both the temporal and spatial ranges will be necessary for long-term tracking under diverse climate contexts. Since the model inputs and codes used in this study are publicly accessible, and land use data are updated annually, expanding the temporal and spatial scope in the future shows high feasibility. When auxiliary data for a longer time series becomes available, the dataset will be updated to serve contemporary research. Additionally, in multi-region or large-scale studies, a 100 m spatial resolution may become redundant, especially in regions with uniform land cover types, including mountainous or desert areas. Therefore, future research should focus more on urban-scale studies, aiming to include more cities and extend the research timeframe, to better capture climate change trends and provide results with broader applicability.

Usage Notes

In this section, we analyze the potential application of our high-resolution temperature dataset. Using the ConvLSTM model, we generated daily maximum, minimum, and mean temperature data at 100 m resolution for the Jiangbei Climate Zone from June to August, 2019–2023. Although our dataset covers only a five-year period, the primary aim of our study is to provide fine-scale data for studying temperature variation in urban and intra-urban environments. In recent years, the rapid development of urban big data technologies has underscored the importance of real-time temperature monitoring. Compared to historical data, this study focuses on the current spatiotemporal distribution of temperature, particularly dynamic changes of the urban high-temperature distribution. Our dataset can provide essential support for studies on the urban heat island effect, climate change assessment, environmental management, and disaster early warning. Additionally, it offers a scientific basis for climate adaptation strategies in urban planning and building design, as well as guidance for equationting heatwave response and mitigation policies. As urbanization accelerates, the demand for monitoring current temperature distributions becomes increasingly urgent. At present, daily temperature datasets with high spatial resolution (100 m) remain relatively scarce. Our downscaling dataset, exhibits high precision in both spatial and temporal scales, as well as good spatial heterogeneity across different spatial resolutions, making it both practical and valuable for urban climate research and applications.

Code availability

Codes used in this study are available at https://github.com/Mengqi-Sun/ConvLSTM-for-Temperature-Downscaling.

References

IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V. et al (Eds.)]. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896 (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

He, C. et al. Exploring the mechanisms of heat wave vulnerability at the urban scale based on the application of big data and artificial societies. Environment International 127, 573–583 (2019).

Qian, J. et al. High spatial and temporal resolution multi-source anthropogenic heat estimation for China. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 203, 107451 (2024).

Zheng, Z., Lin, X., Chen, L., Yan, C. & Sun, T. Effects of urbanization and topography on thermal comfort during a heat wave event: A case study of Fuzhou, China. Sustainable Cities and Society 102, 105233 (2024).

Chen, K., Boomsma, J. & Holmes, H. A. A multiscale analysis of heatwaves and urban heat islands in the western U.S. during the summer of 2021. Sci Rep 13, 9570 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Modeling the Warming Impact of Urban Land Expansion on Hot Weather Using the Weather Research and Forecasting Model: A Case Study of Beijing, China. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 35, 723–736 (2018).

Li, J. & Heap, A. D. A review of comparative studies of spatial interpolation methods in environmental sciences: Performance and impact factors. Ecological Informatics 6, 228–241 (2011).

PENG Bin, ZHOU Yanlian, GAO Ping, & JU Weimin. Suitability Assessment of Different Interpolation Methods in the Gridding Process of Station Collected Air Temperature:A Case Study in Jiangsu Province,China. Journal of Geo-Information Science 13, 539–548 (2011).

Xu, S., Wang, D., Liang, S., Liu, Y. & Jia, A. Assessment of gridded datasets of various near surface temperature variables over Heihe River Basin: Uncertainties, spatial heterogeneity and clear-sky bias. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 120, 103347 (2023).

Russo, S., Sillmann, J. & Fischer, E. M. Top ten European heatwaves since 1950 and their occurrence in the coming decades. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 124003 (2015).

Hu, Y. et al. Spatial characterization of global heat waves using satellite-based land surface temperature. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 125, 103604 (2023).

Hu, D. et al. A novel dual-layer composite framework for downscaling urban land surface temperature coupled with spatial autocorrelation and spatial heterogeneity. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 130, 103900 (2024).

Liu, W. et al. Nonlinear effects of urban multidimensional characteristics on daytime and nighttime land surface temperature in highly urbanized regions: A case study in Beijing, China. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 132, 104067 (2024).

Mostovoy, G. V., King, R. L., Reddy, K. R., Kakani, V. G. & Filippova, M. G. Statistical Estimation of Daily Maximum and Minimum Air Temperatures from MODIS LST Data over the State of Mississippi. GIScience & Remote Sensing 43, 78–110 (2006).

Mutiibwa, D., Strachan, S. & Albright, T. Land Surface Temperature and Surface Air Temperature in Complex Terrain. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 8, 4762–4774 (2015).

Jin, M. & Dickinson, R. E. Land surface skin temperature climatology: benefitting from the strengths of satellite observations. Environ. Res. Lett. 5, 044004 (2010).

Williamson, S. N. et al. Spring and summer monthly MODIS LST is inherently biased compared to air temperature in snow covered sub-Arctic mountains. Remote Sensing of Environment 189, 14–24 (2017).

Jiang, Y. et al. A downscaling approach for constructing high-resolution precipitation dataset over the Tibetan Plateau from ERA5 reanalysis. Atmospheric Research 256, 105574 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. Creating 1-km long-term (1980–2014) daily average air temperatures over the Tibetan Plateau by integrating eight types of reanalysis and land data assimilation products downscaled with MODIS-estimated temperature lapse rates based on machine learning. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 97, 102295 (2021).

Hu, W., Scholz, Y., Yeligeti, M., von Bremen, L. & Deng, Y. Downscaling ERA5 wind speed data: a machine learning approach considering topographic influences. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 094007 (2023).

Xu, Z. & Yang, Z.-L. An Improved Dynamical Downscaling Method with GCM Bias Corrections and Its Validation with 30 Years of Climate Simulations. Journal of Climate 25, 6271–6286 (2012).

Guo, D. & Wang, H. Comparison of a very-fine-resolution GCM with RCM dynamical downscaling in simulating climate in China. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 33, 559–570 (2016).

Wang, H., Yin, S., Yue, T., Chen, X. & Chen, D. Developing a dynamic-statistical downscaling framework for wind speed prediction for the Beijing 2022 Winter olympics. Clim Dyn 62, 7345–7363 (2024).

Shen, H. et al. Deep learning-based air temperature mapping by fusing remote sensing, station, simulation and socioeconomic data. Remote Sensing of Environment 240, 111692 (2020).

Wang, R., Gao, W. & Peng, W. Spatial downscaling method for air temperature through the correlation between land use/land cover and microclimate: A case study of the Greater Tokyo Area, Japan. Urban Climate 40, 101003 (2021).

Yao, R. Global seamless and high-resolution temperature dataset (GSHTD), 2001–2020. Remote Sensing of Environment (2023).

Qin, R. et al. HRLT: a high-resolution (1 d, 1 km) and long-term (1961–2019) gridded dataset for surface temperature and precipitation across China. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 4793–4810 (2022).

Shi, X. et al. Convolutional LSTM network: a machine learning approach for precipitation nowcasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 28 (2015).

Niu, D. et al. Precipitation Forecast Based on Multi-channel ConvLSTM and 3D-CNN. in 2020 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS) 367–371, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICUAS48674.2020.9213930 (2020).

Mukherjee, A., Panda, J., Choudhury, A., Singh, S. & Bhattacharyya, S. Analyzing urban footprints over four coastal cities of India and the association with rainfall and temperature using deep learning models. Urban Climate 57, 102123 (2024).

Zheng, L., Lu, W. & Zhou, Q. Weather image-based short-term dense wind speed forecast with a ConvLSTM-LSTM deep learning model. Building and Environment 239, 110446 (2023).

Lee, Y. et al. Application of deep learning in cloud cover prediction using geostationary satellite images. GIScience & Remote Sensing 62, 2440506 (2025).

Zhao, C., Jensen, J. L. R., Weng, Q., Currit, N. & Weaver, R. Use of Local Climate Zones to investigate surface urban heat islands in Texas. GIScience & Remote Sensing 57, 1083–1101 (2020).

Yang, J. & Huang, X. The 30 m annual land cover dataset and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth System Science Data 13, 3907–3925 (2021).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth System Science Data 13, 4349–4383 (2021).

Molla, A., Sailor, D. J. & Flores, A. B. Exploring air temperature variability and socio-demographic inequalities in heat exposure through machine learning: A case study of Maricopa County, Arizona. Urban Climate 59, 102276 (2025).

Gao, J., Meng, Q., Zhang, L. & Hu, D. How does the ambient environment respond to the industrial heat island effects? An innovative and comprehensive methodological paradigm for quantifying the varied cooling effects of different landscapes. GIScience & Remote Sensing 59, 1643–1659 (2022).

Meng, Q. et al. Coupled cooling effects between urban parks and surrounding building morphologies based on the microclimate evaluation framework integrating remote sensing data. Sustainable Cities and Society 102, 105235 (2024).

Cui, B. et al. Distribution and Growth Drivers of Oases at a Global Scale. Earth’s Future 12, e2023EF004086 (2024).

Wang, M., Wei, J., Wang, X., Luan, Q. & Xu, X. Reconstruction of all-sky daily air temperature datasets with high accuracy in China from 2003 to 2022. Sci Data 11, 1133 (2024).

Ding, Y. & Peng, S. Spatiotemporal Trends and Attribution of Drought across China from 1901–2100. Sustainability 12, 477 (2020).

Peng, S. et al. Spatiotemporal change and trend analysis of potential evapotranspiration over the Loess Plateau of China during 2011–2100. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 233, 183–194 (2017).

Peng, S., Gang, C., Cao, Y. & Chen, Y. Assessment of climate change trends over the Loess Plateau in China from 1901 to 2100. International Journal of Climatology 38, 2250–2264 (2018).

Peng, S., Ding, Y., Liu, W. & Li, Z. 1 km monthly temperature and precipitation dataset for China from 1901 to 2017. Earth System Science Data 11, 1931–1946 (2019).

Sun, M. Summer Daily Scale 100m Maximum, Minimum, and Average Temperature Dataset in Jiangbei Climate Zone, China (2019–2023). National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center. https://doi.org/10.11888/Atmos.tpdc.302013 (2025).

Buster, G., Benton, B. N., Glaws, A. & King, R. N. High-resolution meteorology with climate change impacts from global climate model data using generative machine learning. Nat Energy 9, 894–906 (2024).

Zhu, B. China’s Climate. Science Press, Beijing (1962).

Chinese Academy of Sciences, Natural Regionalization Working Committee. China’s Climate Regionalization. Science Press, Beijing (1959).

Zhu K. On China’s climatic regions. J. Meteorol. Res. Inst. 1 (1931).

Jarvis, A., Guevara, E., Reuter, H. I. & Nelson, A. D. Hole-filled SRTM for the globe: version 4: data grid. (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Major Program [42192580, 42192581], the National Natural Science Foundation of China [42201384], FY-3 Lot 03 Meteorological Satellite Engineering Ground Application System Ecological Monitoring and Assessment Application Project (Phase I)[ZQC-R22227], and Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS [2023139]. The dataset is provided by National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center (http://data.tpdc.ac.cn). Moreover, the authors would like to thank Prof. Li Feng from the College of Geography and Remote Sensing, Hohai University, Prof. Torsten Juelich from the Department of Foreign Languages, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, and Prof. Yizhou Fan from the Graduate School of Education, Peking University, for their practical guidance during previous courses and tutoring, which significantly enhanced the efficiency and quality of the paper writing process. We also wish to express our gratitude to the handling editor and all the reviewers for the constructive comments and suggestions, which greatly contributed to improving the quality of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mengqi Sun: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Qingyan Meng: Funding acquisition, Writing - Review & Editing. Linlin Zhang: Funding acquisition, Writing - Review & Editing. Xinli Hu: Funding acquisition, Writing - Review & Editing. Xuewen Lei: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing. Shize Chen: Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing. Junyan Hou: Funding acquisition, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, M., Meng, Q., Zhang, L. et al. Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory network for generating 100 m daily near-surface air temperature. Sci Data 12, 749 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05032-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05032-6