Abstract

Dengue fever has been spreading rapidly worldwide, with a notably high prevalence in South American countries such as Brazil. Its transmission dynamics are governed by the vector population dynamics and the interactions among humans, vectors, and pathogens, which are further shaped by environmental factors. Calculating these environmental indicators is challenging due to the limited spatial coverage of weather station observations and the time-consuming processes involved in downloading and processing local data, such as satellite imagery. This issue is exacerbated in large-scale studies, making it difficult to develop comprehensive and publicly accessible datasets of disease-influencing factors. Addressing this challenge necessitates the efficient data integration methods and the assembly of multi-factorial datasets to aid public health authorities in understanding dengue transmission mechanisms and improving risk prediction models. In response, we developed a population-weighted dataset of 12 dengue risk factors, covering 558 microregions in Brazil over 1252 epidemiological weeks from 2001 to 2024. This dataset and the associated methodology streamline data processing for researchers and can be adapted for other vector-borne disease studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background and Summary

Dengue fever is an acute viral infectious disease transmitted by mosquitoes and is widely distributed in urban or semi-urban areas in more than 100 countries and regions in the tropics and subtropics worldwide, posing a serious threat to people’s lives and health1. In 2024, approximately 90 countries have so far reported active dengue transmission, and by 5th September, the total number of reported cases had reached more than 11 million in the Americas2. The number of people at risk of dengue is predicted to reach 6.1 billion (4.7–6.9 billion) by 2080, accounting for more than 60% of the world’s population3. Brazil, facing the worst dengue fever situation globally, with a reported 3,088,723 cases in 20234, and over one million cases in the first two months of 20245. Due to the lack of an effective vaccine, accurate and timely dengue risk prediction has become crucial for disease prevention and control5, particularly for the joint management of dengue outbreaks. Utilizing environmental datasets to establish the relationship between factors such as climate, environment, human activities and dengue can support research on dengue mechanisms and improve risk prediction. Epidemiological data in Brazil are publicly available6, and several projects and studies have highlighted the availability of dengue datasets for researchers to investigate transmission mechanisms and develop predictive models7. For example, Info Dengue platform is a hybrid data-based arbovirus alert system consists of three processes: data collection, coordination, and analysis. By a combination of social networks and climate and epidemiological data, it can generate indicators of the epidemiological status of dengue and other arboviruses such as Zika and chikungunya at the municipal level for 788 cities in Brazil8. However, to date, effective methods for calculating dengue environmental factors and the complete and comprehensive Brazilian environmental datasets specifically for studies on dengue transmission mechanisms and risk prediction remain unavailable. Given the critical dengue epidemic in Brazil, establishing a complete set of environmental datasets is essential for analyzing outbreaks and improving prevention and control efforts.

Environmental datasets are of great importance for modeling the spatial and temporal spread of dengue, especially in a country as diverse as Brazil9, where significant heterogeneity exists in the timing and intensity of dengue transmission10. Previous studies have explored the association of numerous environmental factors (e.g., temperature11,12, precipitation13,14, relative humidity15,16, atmospheric pressure17,18, wind speed18, the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI)19, and the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)20,21) with the incidence of dengue. These factors affect the life cycle, survival, and biting rate of Aedes aegypti, as well as the incubation period of the virus, thereby shaping the spatial and temporal patterns of dengue epidemics. Due to the strong hematophagous nature of dengue vectors22 and their limited range of movement, human-to-vector-to-human transmission serves as a key route for the spread of the dengue virus. Consequently, human factors play a significant role in dengue virus transmission. Previous studies have explored the relationship between urbanization19 and dengue risk, as well as the impact of dengue fever on gross domestic product (GDP)23. Most dengue risk prediction studies use environmental factors from weather stations24. However, the limited spatial representativeness of weather station-based observations poses challenges for efficient and accurate dengue risk prediction. In addition, the time-consuming nature of downloading and processing satellite images and ready-to-use data such as PDSI and NDVI further complicates large-scale dengue studies. To address these challenges, it is essential to develop an efficient methodology for constructing a spatiotemporal dataset of dengue influencing factors, enabling more accurate and timely predictions of dengue outbreaks.

In recent years, geospatial big data has become a global focus, attracting increasing attention from various organizations25. It encompasses vast amount of specific types of data with location information, offering tremendous opportunities to advance scientific discoveries across diverse fields, such as climate science, disaster management, public health, precision agriculture and smart cities26. However, the inherent complexity of geospatial big data, characterized by its multi-source, multi-scale, high-dimensional, dynamic, heterogeneous, and non-linear nature, introduces numerous challenges, spanning the entire data lifecycle, from acquisition and storage to searching, sharing, transmission, analysis, and visualization27. There is an urgent need for advanced methods to address these issues in order to fully leverage the potential of geospatial big data. Currently, the main approaches are based on two platforms: cluster-based high-performance computing (HPC) systems and cloud computing platforms28. The introduction and application of cloud computing have significantly reduced the complexity and labor costs associated with dataset creation29. Cloud computing platforms such as Google Earth Engine (GEE), PIE Engine, and Amazon Web Services are widely used. For example, GEE hosts several petabytes of global satellite imagery (e.g., MODIS, Landsat, and Sentinel) and ready-to-use datasets on various themes, such as climate, land cover, agriculture, urbanization, and population. It also supports various algorithms, including image preprocessing, spatial and temporal analysis, and image classification, as well as parallel computing capabilities30,31. GEE has become an important tool in public health research, particularly in the study of infectious diseases like malaria32,33 and Zika34. However, datasets related to the factors influencing dengue transmission remain underdeveloped. Therefore, to produce dengue-related datasets based on GEE, it is essential to identify the appropriate data sources for generating spatial-temporal predictions of environmental factors that affect dengue transmission.

Here, this study presents a geospatial big data cloud-based framework for identifying common environmental factors associated with dengue transmission at the microregion scale, per epidemiological week, in Brazil. The framework aims to facilitate access to publicly available geospatial big data and cloud computing platforms for public health researchers. By specifying the spatial and temporal resolution, and the spatial extent required to generate environmental datasets, as well as by making the methodology and code publicly available, this approach can reduce duplication of efforts in dataset creation.

Methods

Brazil, officially known as the Federal Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America and the fifth largest in the world, and located in the eastern part of South America (Fig. 1). In Brazil, the area of dengue transmission has been expanding southward and toward the central regions of the country35,36. Studies have shown the impact of extreme weather events, such as droughts and floods19, on the distribution of dengue cases. Meanwhile, the economic expansion into the Amazon region through road construction and deforestation has also contributed to the widening of dengue transmission area37,38. In addition, long-term temperature increases have also been shown to play a significant role in this expansion39. Therefore, an integrated consideration of environmental factors related to temperature, precipitation, and urbanization is crucial for understanding dengue transmission mechanisms and improving risk prediction models.

Many studies utilized dengue cases reported by the Sistema de Informação de Agravo de Notificação (SINAN)6,19,40, which reports the dengue cases since 2001. This dataset provides clinical, sociodemographic, and laboratory information on patients with confirmed dengue fever. Currently, most studies on dengue risk in Brazil are conducted at the microregion level10,41. In Brazil, 5570 municipalities are aggregated into 558 microregions, 5 regions (Fig. 1), which are commonly used as spatial units for analyzing the spatial patterns of infectious diseases19. Accordingly, this study established a dataset of environmental factors at the spatial scale of 558 microregions, spanning a temporal scale of 1252 epidemiologic weeks from 2001 to 2024 (Fig. 2).

The proposed framework for generating dengue environmental factors at multiple spatial and temporal scales based on the GEE platform. Part (a) represents the temporal composition of images based on epidemiological weeks and environmental datasets with a population-weighting operation. Part (b) represents the spatial aggregation of image collections to the Brazilian microregional scale.

The dataset presents a list of dengue environmental factors, including (1) total precipitation per week; (2) number of rainy days per week; (3) maximum, mean, and minimum temperatures; (4) mean relative humidity; (5) mean atmospheric pressure; (6) mean wind speed; (7) Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI); (8) mean Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI); (9) Gross Domestic Product (GDP); and (10) building surface area (Table 1).

Population-weighted spatial aggregation

Because the dengue vectors have strong anthropophilic behavior22 and virus-carrying mosquitoes have a limited range of activities, human-to-vector-to-human transmission has become the main route of dengue virus transmission. Therefore, it is necessary to fully consider the distribution of the population while computing the environmental factors in each microregion. The population-weighting operation can reflect the situation of environmental factors in areas with population distribution42. This facilitates further studies such as subsequent integration with the distribution of dengue cases for driver factor identification or risk mapping. In this study, the Brazilian population distribution data derived from WorldPop project dataset43 was used to apply the population-weighting approach to each environmental factor, to reduce the impact of environmental factors in uninhabited areas on the analysis of dengue transmission mechanisms. We selected the Brazilian population data from 2001 to 2020. Due to the lack of population data from 2021 to 2024 in the current WorldPop dataset, we used the 2020 population data to implement the population weighting on the data from 2021 to 2024 in this study.

Sum precipitation and number of rainy days

We obtained precipitation data for Brazil from 2001 to 2024 at a spatial resolution of 11,132 meters through the Earth Engine Data Catalog website (https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/ECMWF_ERA5_LAND_DAILY_AGGR). This dataset originates from the Copernicus Climate Data Store44. ERA5-Land is a high-resolution reanalysis dataset that provides consistent land surface data over decades, enhanced by atmospheric forcing from ERA5 to ensure accuracy45. In this study, we calculated the total precipitation for each microregion during the epidemiologic week. Precipitation here refers to the sum of mass and convective precipitation. The precipitation data, measured as depth (in meters), was convert to millimeters (mm) in GEE. This metric represents the depth of water uniformly distributed over the grid. To describe precipitation frequency, we used the number of rainy days per week. Previous studies have shown a relationship between the frequency of rainy days in a certain time cycle and dengue fever cases46.

Maximum, mean and minimum temperature

We obtained temperature data for Brazil from 2001 to 2024 at a spatial resolution of 11,132 meters through the Earth Engine Data Catalog website (https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/ECMWF_ERA5_LAND_HOURLY). This dataset originates from the Copernicus Climate Data Store45. The temperature represents the hourly air temperature at 2 meters above the surface of the land, ocean, or inland waters. It is calculated by interpolating between the lowest level of the model and the Earth’s surface based on atmospheric conditions45. The dataset provides temperature in kelvin, which we converted to degrees Celsius here.

Mean relative humidity

In this study, since there are no relative humidity dataset at large temporal and spatial scales, we used the dew point temperature and temperature from the ERA5-Land dataset to calculate relative humidity (%). The calculation is based on the Magnus formula:

where Td represents the dew point temperature (°C), and T represents the temperature (°C). We chose the two parameter values of 17.67 and 243.5 °C based on those used in the presentation by NOAA’s47.

Mean atmospheric pressure

We obtained surface pressure data for Brazil from 2001 to 2024 at a spatial resolution of 11,132 meters through the Earth Engine Data Catalog (available from https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/ECMWF_ERA5_LAND_HOURLY). This dataset was sourced from the Copernicus Climate Data Store45. Surface pressure, measured in Pascals (Pa), indicates the atmospheric force per unit area at a given location, representing the weight of the air column above that point.

Mean wind speed

We also obtained wind speed data for Brazil from 2001 to 2024 at a spatial resolution of 11,132 meters through the Earth Engine Data Catalog (https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/ECMWF_ERA5_LAND_HOURLY). This dataset was sourced from the Copernicus Climate Data Store. The data, measured in meters per second (m/s), includes both the eastward (U component) and northward (V component) wind components at a height of 10 meters. To calculate the total wind speed, we combined these components using the following formula:

where U represents the eastward wind speed component (m/s), and V represents the northward wind speed component (m/s).

Palmer drought severity index

The Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) dataset used in this study was sourced from TerraClimate48 in the Earth Engine Data Catalog (https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/IDAHO_EPSCOR_TERRACLIMATE). This dataset has a monthly temporal resolution and a spatial resolution of 4638.3 meters.

Mean normalized difference vegetation index

We obtained the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) data for Brazil from 2001 to 2022 at a spatial resolution of 463.3 meters through the Earth Engine Data Catalog (https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/MODIS_MOD09GA_006_NDVI). This dataset was sourced from the NASA LP DAAC at the USGS EROS Center. NDVI is a value between -1 and 1 which has widely used in environmental health studies49. 0 represents the absence of vegetation. Scores which close to 1 represent the highest possible density of vegetation. On the contrary, scores which close to -1 represent the presence of water50.

Gross domestic product

The gross domestic product (GDP) dataset used in this study is based on the calibrated nighttime light data51. This dataset has a spatial resolution of 1 km and a temporal resolution spanning from 1992 to 2019. The unit of the GDP index is millions of US dollars (2017 valuation). For this study, we obtained the 2001–2019 yearly GDP values and calculated them in 558 microregions.

Building surface area

In this study, we used built-up surface as an indicator of urbanization. We obtained data on the building surface area for each microregion in Brazil from the GHSL (Global Human Settlement Layer) dataset52. The GHS-BUILT-S product, derived from Sentinel-2 composite and Landsat, includes the data on both the total built-up surface and the built-up surface allocated to dominant non-residential uses53. The dataset provides data for five years (2000, 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2020) with the built-up surface data spatially-temporally interpolated or extrapolated from 1975 to 2030 at five-year intervals. The spatial resolution is 100 meters. In GEE, we calculated the building surface area in 558 microregions by extending the values contained in the GHSL dataset backward by 4 years to obtain complete annual data from 2001 to 2024. Figure 3(l) shows the building surface area in square kilometers (km2) in 2019.

Illustrative maps of microregion-level dengue-associated factors. The factors include minimum temperature (a), mean temperature (b), maximum temperature (c), total precipitation (d), number of rainy days (e), mean relative humidity (f), mean NDVI (g), mean pressure (h), mean wind speed (i), PDSI (j), GDP (k), and building surface area (l). (a–i) shows the factors in a single epidemiological week (15th epidemiological week of 2019); (j) shows the PDSI in April 2019; (k,l) shows the GDP and building surface area in 2019.

The graphs below show the spatial distribution of dengue-associated factors across 558 microregions in the 15th epidemiological week, 2019 (Fig. 3) and the temporal distribution of dengue-associated factors in the Federal District of Brazil, identified as microregion 53001 (Fig. 4). The factors shown in Fig. 4 are recorded in the dataset on a daily or hourly basis, which are suitable for time series analysis.

Data Records

All output datasets described in this article are publicly and freely available through the Zenodo Repository54 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15091652). The dataset contains 12 CSV files of dengue-related factors and a zip file of 558 microregions in Brazil. The first line of all CSV files includes the time of each variable, and each column contains the specific data of 558 microregions at each time.

Technical Validation

Meteorological grid-based datasets are usually generated through numerical weather prediction models that integrate multiple data sources, such as weather station observations, satellite remote sensing, radar, etc. These data are interpolated or assimilated to provide meteorological information covering extensive areas55,56. Therefore, the accuracy of such data is affected by both the model used and the data processing methods. Although weather station data are often considered accurate observations, they are limited to the specific locations of the stations and cannot be generalized for large-scale studies. Therefore, for dengue transmission studies at the national microregion level, the use of high-spatial-resolution grid-based datasets is essential. The ERA5-Land dataset used in this study is a land surface reanalysis dataset derived from ECMWF’s ERA5 atmospheric reanalysis data45. It uses the same meteorological forcings (e.g., precipitation, temperature, radiation) as ERA5 but runs the land surface model (HTESSEL)57 at a higher spatial resolution. It should be noted that ERA5-Land does not directly assimilate land observations but instead relies on atmospheric conditions provided by ERA5. To validate the datasets we produced by ERA5-land, we compare it with daily data from more than 200 conventional weather stations in Brazil, sourced from the National Institute of Meteorology (Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia, INMET). This dataset contains meteorological data from 1961 to 2019, with 6 variables selected for analysis: (a) precipitation, (b) relative humidity, (c) minimum temperature, (d) maximum temperature, (e) atmospheric pressure, and (f) wind speed (Fig. 5).

Illustrative maps of Pearson correlation coefficient between conventional weather station data of the National Institute of Meteorology in Brazil and the generated data: (a) precipitation, (b) relative humidity, (c) minimum temperature, (d) maximum temperature, (e) atmospheric pressure, and (f) wind speed.

Since the datasets we generated are population-weighted, and the distribution of the population has a large impact on the results during the validation process. We aimed to ensure that the weather station locations were situated in densely populated areas relative to the average population density in each microregion. Therefore, in the process of verifying the validity of the dataset, we selected data from meteorological stations located in densely populated areas. This approach allows for meaningful comparison between the weather station observations and the population-weighted data.

The verification process included the following steps: 1) In the Google Earth Engine platform, we first calculated the average population density of each microregion and the population density at the pixel where each weather station is located. We then removed stations located in sparsely populated areas. 2) Given temporal resolution of our data, we calculated daily weather values and resampled them based on epidemiological week in 2019. 3) To assess the reliability of the population-weighted dataset obtained in this study, we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficients and p-values for the six variables and their corresponding observations. 4) Since data from conventional weather stations are missing at certain time points and for specific variables, we excluded these weather stations with missing values from the calculation of the Pearson correlation coefficients and p-values.

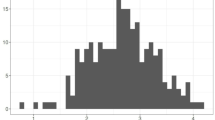

We used the data in 2019 to carry out the above-mentioned steps. We selected 100 weather stations from 265 conventional weather stations of the National Institute of Meteorology. The data showed that the average Pearson correlation coefficient and p-value for weekly precipitation totals across 77 stations was 0.61 and 0.01, respectively, while for weekly mean relative humidity, it was 0.78 and 0.02 across 70 stations, respectively. The average Pearson correlation coefficients for maximum and minimum temperatures were 0.66 and 0.71, and their p-values were 0.06 and 0.05 respectively. For atmospheric pressure and wind speed, the Pearson correlation coefficients were 0.83 and 0.58 for 59 and 53 stations, and their p-values were 0.07 and 0.11 respectively. Figure 5 shows the distribution of the Pearson correlation coefficients for the six weather factors across microregions. The verification process showed that the datasets we generated have a strong linear relationship with the weather station data at the spatiotemporal scale. Given that the population distribution factors in our dataset influence the values, we conclude that the dataset produced in this study is reliable. Figure 6 shows the example comparison of the conventional weather station data and the population-weighted data over time of 52 epidemiology weeks in 2019 (weather station code: 43428, microregion code: 31001).

Usage Notes

The datasets compiled in this study can be used for research related to dengue risk prediction and the identification of driving factors in Brazil. The dataset can also help public health departments implement microregion-level dengue prevention strategies. In addition, the dataset is also applicable to studies of other vector-borne infectious diseases, such as chikungunya58 and yellow fever59, which have the same vectors (i.e., Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus). However, this dataset has several limitations that should be noted while using our data. First, due to the absence of population data from 2021 to 2024 in the WorldPop dataset, we used the 2020 population data to perform population weighting on the data from 2021 to 2024 based on the assumption that the population will not change significantly in the few years. We plan to update the dataset with the latest WoldPop population data as it becomes available. Second, the resolution constraints of both the factors and population data may limit the applicability of our method to microregion scales or larger spatial scales (e.g., mesoregions in Brazil). For municipality-level analysis, higher-resolution data would be better. Third, the large-scale climate raster data currently available on the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform are generally derived from a combination of numerical meteorological models and observational data. The data assimilation outcomes may exhibit systematic biases, particularly in regions with sparse observational coverage60. Last, it is important to note that variables such as GDP and building surface area change on an annual basis, so this study does not capture changes in the economy or urbanization process on an epidemiological weekly scale.

Code availability

The code used to generate the microregion-level dengue-associated factor datasets in Google Earth Engine, and the code for processing the generated data are freely available for download from GitHub (https://github.com/663z/Spatiotemporal-dataset-of-dengue-influencing-factors-in-Brazil.git). These codes were written in JavaScript and Python version 3.13.0.

References

Murray, N. E., Quam, M. B. & Wilder-Smith, A. Epidemiology of dengue: past, present and future prospects. Clin Epidemiol 5, 299–309, https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S34440 (2013).

Venkatesan, P. Global upsurge in dengue in 2024. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 24, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00609-1 (2024).

Messina, J. P. et al. The current and future global distribution and population at risk of dengue. Nature Microbiology 4, 1508–1515, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-019-0476-8 (2019).

Haider, N., Hasan, M. N., Onyango, J. & Asaduzzaman, M. Global landmark: 2023 marks the worst year for dengue cases with millions infected and thousands of deaths reported. IJID Regions 13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijregi.2024.100459 (2024).

Lenharo, M. Brazil’s record dengue surge: why a vaccine campaign is unlikely to stop it. Nature 627, 250–251, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-00626-3 (2024).

da Silva Neto, S. R. et al. Arboviral disease record data - Dengue and Chikungunya, Brazil, 2013–2020. Scientific Data 9, 198, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01312-7 (2022).

Coelho, G. E., Leal, P. L., Cerroni Mde, P., Simplicio, A. C. & Siqueira, J. B. Jr. Sensitivity of the Dengue Surveillance System in Brazil for Detecting Hospitalized Cases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10, e0004705, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004705 (2016).

Codeco, C. et al. Infodengue: A nowcasting system for the surveillance of arboviruses in Brazil. Revue d'Épidémiologie et de Santé Publique 66, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respe.2018.05.408 (2018).

Ogashawara, I., Li, L. & Moreno-Madrinan, M. J. Spatial-Temporal Assessment of Environmental Factors Related to Dengue Outbreaks in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Geohealth 3, 202–217, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GH000186 (2019).

Lowe, R. et al. Evaluating probabilistic dengue risk forecasts from a prototype early warning system for Brazil. Elife 5, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.11285 (2016).

Salim, K. U. et al. Socioeconomic and environmental factors associated with dengue fever incidence in Guatemala: Rising temperatures increase dengue risk. PloS one 19, e0308271, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0308271 (2024).

Seposo, X., Valenzuela, S. & Apostol, G. L. Socio-economic factors and its influence on the association between temperature and dengue incidence in 61 Provinces of the Philippines, 2010–2019. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 17, e0011700–e0011700, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0011700 (2023).

Geraldini, B., Johansen, I. C. & Justus, M. Influence of temperature and precipitation on dengue incidence in Campinas, São Paulo State, Brazil (2013-2022). Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical 57, e007102024, https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0080-2024 (2024).

Borges, I. V. G. et al. Analysis of the interrelationship between precipitation and confirmed dengue cases in the city of Recife (Brazil) covering climate and public health information. Frontiers in public health 12, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1456043 (2024).

Alkhaldy, I. Modelling the association of dengue fever cases with temperature and relative humidity in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia—A generalised linear model with break-point analysis. Acta tropica 168, 9–15, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.12.034 (2017).

Figueredo, M. B. et al. Analysis of the correlation between climatic variables and Dengue cases in the city of Alagoinhas/BA. Scientific Reports 2023 13:1 13, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34349-8 (2023).

Zhu, B. et al. Prediction model for dengue fever based on interactive effects between multiple meteorological factors in Guangdong, China (2008–2016). PLOS ONE 14, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225811 (2019).

Gómez, R. E. G. et al. Association between Climate Factors and Dengue Fever in Asuncion, Paraguay: A Generalized Additive Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912192 (2022).

Lowe, R. et al. Combined effects of hydrometeorological hazards and urbanisation on dengue risk in Brazil: a spatiotemporal modelling study. The Lancet. Planetary health 5, e209–e219, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30292-8 (2021).

Soukavong, M. et al. Bayesian spatio-temporal analysis of dengue transmission in Lao PDR. Scientific Reports 2024 14:1 14, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71807-3 (2024).

Tewari, P. et al. Associations between Dengue Incidence, Ecological Factors, and Anthropogenic Factors in Singapore. Viruses 15, https://doi.org/10.3390/v15091917 (2023).

Nouzova, M., Clifton, M. E. & Noriega, F. G. Mosquito adaptations to hematophagia impact pathogen transmission. Current Opinion in Insect Science 34, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2019.02.002 (2019).

Marczell, K. et al. The Impact of Dengue Fever on Gross Domestic Product: Case Studies from Thailand and Brazil. International journal of infectious diseases 130, S106–S106, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2023.04.263 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Impact of extreme weather on dengue fever infection in four Asian countries: A modelling analysis. Environ Int 169, 107518, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107518 (2022).

Loukili, Y., Lakhrissi, Y. & Ali, S. E. B. Geospatial Big Data Platforms: A Comprehensive Review. KN - Journal of Cartography and Geographic Information 72, 293–308, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42489-022-00121-7 (2022).

Li, Z. in High Performance Computing for Geospatial Applications (eds Wenwu Tang & Shaowen Wang) 53-76 (Springer International Publishing, 2020).

Liu, P. A survey of remote-sensing big data. Frontiers in Environmental Science 3, https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2015.00045 (2015).

Ma, Y. et al. Remote sensing big data computing: Challenges and opportunities. Future Generation Computer Systems 51, 47–60, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2014.10.029 (2015).

ArmbrustMichael et al. A view of cloud computing. Communications of the ACM, https://doi.org/10.1145/1721654.1721672 (2010).

Amani, M. et al. Google Earth Engine Cloud Computing Platform for Remote Sensing Big Data Applications: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 13, 5326–5350, https://doi.org/10.1109/jstars.2020.3021052 (2020).

Tamiminia, H. et al. Google Earth Engine for geo-big data applications: A meta-analysis and systematic review. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 164, 152–170, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2020.04.001 (2020).

Wimberly, M. C., Beurs, K. M. d., Loboda, T. V. & Pan, W. K. Satellite Observations and Malaria: New Opportunities for Research and Applications. Trends in Parasitology 37, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2021.03.003 (2021).

Wimberly, M. C. et al. Cloud-based applications for accessing satellite Earth observations to support malaria early warning. Scientific Data 2022 9:1 9, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01337-y (2022).

Belaunzarán-Zamudio, P. F. et al. Frontiers | Comparison of the Impact of Zika and Dengue Virus Infection, and Other Acute Illnesses of Unidentified Origin on Cognitive Functions in a Prospective Cohort in Chiapas Mexico. Frontiers in Neurology 12, https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.631801 (2021).

Barcellos, C. & Lowe, R. Expansion of the dengue transmission area in Brazil: the role of climate and cities. Tropical Medicine & International Health 19, 159–168, https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12227 (2014).

Codeço, C. T., Villela, D. A. M. & Coelho, F. C. Estimating the effective reproduction number of dengue considering temperature-dependent generation intervals. Epidemics 25, 101–111, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epidem.2018.05.011 (2018).

Lana, R. M., Gomes, M. F. D. C., Lima, T. F. M. D., Honório, N. A. & Codeço, C. T. The introduction of dengue follows transportation infrastructure changes in the state of Acre, Brazil: A network-based analysis. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 11, e0006070, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006070 (2017).

Lowe, R. et al. Emerging arboviruses in the urbanized Amazon rainforest. BMJ 371, m4385, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4385 (2020).

Barcellos, C., Matos, V., Lana, R. M. & Lowe, R. Climate change, thermal anomalies, and the recent progression of dengue in Brazil. Scientific Reports 14, 5948, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56044-y (2024).

Churakov, M., Villabona-Arenas, C. J., Kraemer, M. U. G., Salje, H. & Cauchemez, S. Spatio-temporal dynamics of dengue in Brazil: Seasonal travelling waves and determinants of regional synchrony. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 13, e0007012, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007012 (2019).

Lowe, R. et al. Dengue outlook for the World Cup in Brazil: an early warning model framework driven by real-time seasonal climate forecasts. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 14, 619–626, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(14)70781-9 (2014).

Siraj, A. S. et al. Spatiotemporal incidence of Zika and associated environmental drivers for the 2015-2016 epidemic in Colombia. Sci Data 5, 180073, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2018.73 (2018).

Sorichetta, A. et al. High-resolution gridded population datasets for Latin America and the Caribbean in 2010, 2015, and 2020. Scientific Data 2015 2:1 2, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2015.45 (2015).

Muñoz Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-land post-processed daily-statistics from 1950 to present. https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.e9c9c792 (2024).

Muñoz Sabater, J. ERA5-Land hourly data from 1950 to present. https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.e2161bac (2019).

Rahman, K. M. et al. An Association between Rainy Days with Clinical Dengue Fever in Dhaka, Bangladesh: Findings from a Hospital Based Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249506 (2020).

Bolton, D. The Computation of Equivalent Potential Temperature. Monthly Weather Review 108, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0493(1980)1081046:TCOEPT2.0.CO;2.

Abatzoglou, J. T. et al. TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015. Scientific Data 2018 5:1 5, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.191 (2018).

Cunha, Md. C. M. et al. Disentangling associations between vegetation greenness and dengue in a Latin American city: Findings and challenges. Landscape and Urban Planning 216, 104255, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104255 (2021).

Rojas-Rueda, D., Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J., Gascon, M., Perez-Leon, D. & Mudu, P. Green spaces and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Lancet Planet Health 3, e469–e477, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30215-3 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Global 1 km × 1 km gridded revised real gross domestic product and electricity consumption during 1992–2019 based on calibrated nighttime light data. Scientific Data 2022 9:1 9, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01322-5 (2022).

European Commission: Joint Research, C. GHSL data package 2023. (Publications Office of the European Union, 2023).

Pesaresi M., P. P. GHS-BUILT-S R2023A - GHS built-up surface grid, derived from Sentinel2 composite and Landsat, multitemporal (1975–2030). https://doi.org/10.2905/9F06F36F-4B11-47EC-ABB0-4F8B7B1D72EA (2023).

Zhu, Q. et al. Spatiotemporal dataset of dengue influencing factors in Brazil based on geospatial big data cloud computing. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15091652 (2025).

Weyn, J. A., Durran, D. R., Caruana, R. & Cresswell-Clay, N. Sub-Seasonal Forecasting With a Large Ensemble of Deep-Learning Weather Prediction Models. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems 13, e2021MS002502, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021MS002502 (2021).

Eyre, J. R., English, S. J. & Forsythe, M. Assimilation of satellite data in numerical weather prediction. Part I: The early years. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 146, 49–68, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3654 (2020).

Balsamo, G. et al. A Revised Hydrology for the ECMWF Model: Verification from Field Site to Terrestrial Water Storage and Impact in the Integrated Forecast System. Journal of Hydrometeorology 10, 623–643, https://doi.org/10.1175/2008JHM1068.1 (2009).

Nunes, M. R. T. et al. Emergence and potential for spread of Chikungunya virus in Brazil. BMC Medicine 13, 102, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0348-x (2015).

Wint, W., Jones, P., Kraemer, M., Alexander, N. & Schaffner, F. Past, present and future distribution of the yellow fever mosquito Aedes aegypti: The European paradox. Science of The Total Environment 847, 157566, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157566 (2022).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 146, 1999–2049, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFF0802400).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.Z., Z.L. and J.D. designed the study and the methodology, Q.Z. and Z.L. wrote the code and generated the dataset. All authors analyzed the dataset, wrote and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, Q., Li, Z., Dong, J. et al. Spatiotemporal dataset of dengue influencing factors in Brazil based on geospatial big data cloud computing. Sci Data 12, 712 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05045-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05045-1