Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has illuminated the utility of pathogen genomics and highlighted roadblocks to international data sharing. This article describes the deferred value of pathogen genomics data for secondary use using a set of 10,110 assembled genomes of Vibrio cholerae shared via international repositories between 2010 and 2024 as an illustrative representation of a pandemic disease. Trends in the quality, representativeness, and timeliness of data sharing as well as the increasing role of microbiology services as genomic data providers resulting from gradually improving access to sequencing technologies in countries with a high burden of disease were identified. The deferred value of individual and aggregated genomic data was tracked over time and mapped to geographical hot spots of cholera. The time lag between the collection of the samples for V. cholerae cultures and the submission of the genome to an international database remained eight years on average. The data value assessment described here paves the way for the international mobilization of quality microbial genomic data for global health and knowledge discovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Advances in microbial genomics have fundamentally reshaped our understanding of infectious diseases and their transmission. The COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the uptake of microbial sequencing for communicable disease control1 and international microbial genomics data sharing has become the foundation for surveillance to thwart future pandemics and epidemics2,3,4. Infectious disease control programmes include genomics-based surveillance as an integral strategy towards the control and elimination of these diseases5. Initiatives such as WHO Pandemic Treaty and the International Health Regulations have promoted international data sharing for global health6,7. However, disparities in access to high throughput sequencing and concerns about governance of shared genomics data remain major roadblocks for international data mobilisation4,8,9. Unsurprisingly, up to 37% of countries with the capacity for reporting on SARS-CoV-2 variants uploaded less than half of their sequences of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern to international public repositories10.

Genome sequencing data has been recognised as an important intangible asset and the potential for a unique value added by the aggregation of international pathogen genomics data is immense11. Benefits of surveillance data linkage include more accurate data less prone to selection bias, the ability to study health in population-based cohorts, and improved case finding and contact tracing12,13. The utility of microbial genomics data has been gradually expanded from applied research to public health response, modelling of diseases and preventive interventions as well as the design of drugs and vaccines2,3,11,14. This new value extracted from timely and quality sequencing data and metadata is also critical for artificial intelligence (AI)-ready markets for genomic diagnostics and therapeutics15. However, a lack of contextual metadata accompanying shared sequences significantly limits the utility of pathogen genomic data in open databases and their impact on knowledge discovery and global health. Furthermore, the growing amount of sequencing data existing as “UJAD” (i.e. “unpublished in journals and available in databases”) remains internationally unseen and underutilised.

With the exponential growth of sequencing data, more attention is placed on improving data quality, especially for collaborative deep learning and other AI pipelines16. Here we describe the main features that define the value of microbial genomics data for secondary use which would facilitate and optimise the international mobilisation of genomic data. We employed Vibrio cholerae genomes shared via international repositories as an illustrative representation of a pandemic disease which is a target for elimination (see Methods and Supplementary Table S1). This pathogen remains endemic world-wide, causes sporadic outbreaks elsewhere and is responsible for at least 2.9 million cases of acute diarrheal disease each year17. There are thousands of strains of V. cholerae ranging from low-virulence environmental strains to those capable of causing pandemic cholera. Over the past 200 years, seven pandemics of cholera have been recorded. The current seventh pandemic started in 1961 and has been associated with the evolution of the pathogen that migrated throughout Asia and gradually acquired important virulence-associated elements18. While only the O1 and O139 serogroups of V. cholerae have been responsible for pandemics, other serogroups can cause sporadic cases and outbreaks of diarrhoea and systemic disease in vulnerable populations and act as evolutionary intermediaries in virulence gene acquisition17. The genomics of V. cholerae have been examined by many international groups and have been instrumental in the development and evaluation of vaccines.

The value of pathogen sequencing data can be defined by the nature of disease caused by this pathogen and by the availability of associated clinical, epidemiological and other contextual data (i.e. ‘metadata’)3,19. The larger the sets of shared genome sequences are, the more representative they can be of current disease activity and the more likely clusters of infections with a common and removable source can be identified and acted upon. For example, each additional 1,000 genomes of foodborne bacteria added to a national database in the USA could lead to a reduction of ~6 cases per pathogen per year20.

Each sequenced genome of a medically relevant microorganism is expected to have immediate value for the case management or disease control realised at the site of testing in order to justify the cost of sequencing. The focus of this paper, however, is on the deferred value of genome sequences and their associated metadata which can be realised nationally and internationally following data sharing. This deferred (sometimes also referred to as latent) value has usually been demonstrated by the re-analysis or secondary analysis of openly shared genomes. Some examples of deferred value extracted from microbial genomics data are listed in Table 1 and illustrate the importance of relevant contextual metadata for extracting such value as well as current trend of sequencing data reuse which is independent of extensive metadata provisions.

Results

We define the deferred value or reusability of shared data within a single genome as a function of four variables: data quality, novelty, associated metadata – which includes provenance and phenotype data for the microbial strain and the infected host – and the timeliness of genomic data release after the sample collection. The deferred value score was designed to identify anticipated utility for data aggregation and re-use among large sets of microbial genomic data available for secondary analysis (see Methods). This combined score allows a comparison of the value of individual sequences. It should minimise the utility of highly similar genomes from the same location with no contextual metadata and highlight genomes of potential value for data aggregation.

The value index of a collection of genomes represents their aggregated deferred value. It is based on the average value of the individual genomes in the collection, with a correction for the genomic diversity (see Methods). The diversity correction recognises that genomic datasets are typically of greater deferred value when they encompass a representative sample of a larger microbial population rather than focussing on closely related strains from a single outbreak.

Evolution of the nature of international pathogen genomic data sharing

We collected metadata and sequences of all 10,110 assembled genomes of V. cholerae submitted to NCBI GenBank between 2010 and 11 April 2024. We observed exponential growth of genomic data (Fig. 1) reflecting the gradual improvements in sequencing capability in cholera endemic countries (Fig. 2) over this period.

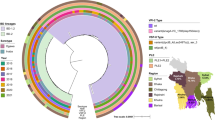

Choropleth map of V. cholerae assembled genome submissions to NCBI GenBank. Countries with high cholera burden estimates in each WHO region are labelled56. The number of assembled genomes on NCBI GenBank is reflected by colour, and the proportion of these that belong to the pandemic O1 or O139 serogroups based on in silico serotyping in our analysis is indicated.

The majority of genomic data was provided by countries with advanced economies, and the regions where cholera is endemic remained under-represented (Figs. 2, 3A). A total of 9,213 genomes could be in silico serogrouped, of which 65% (5,970/9,213) were O1 and 6.1% (567/9,213) were O139. The remainder constituted less virulent serotypes, which might be less relevant for epidemic disease control but are nevertheless important for understanding diversity and ecological niches. Cholera remains endemic (i.e. over 10 cases per 10,000 population) in 49 countries of Africa and Asia (Ending Cholera Report, 2017)21 but only 25 of them were represented in the dataset as sample origins, and only six of these (i.e. People’s Republic of China, Bangladesh, Mozambique, Ghana, India, and Sudan) as sequence submitters. Importantly, while academic institutions (i.e. universities and research institutes) as early adopters of the sequencing technologies were dominant suppliers of genomic data at the start of the period, microbiology service providers (i.e. public health and diagnostic laboratories) have significantly increased their input as genomic data providers. In 2023, the most recent complete year, microbiology service providers accounted for over 80% (532/655) of submitted V. cholerae genomes and over 50% (12/23) of submitting institutions (Fig. 3B).

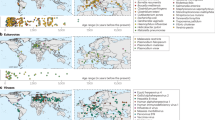

The context of NCBI GenBank V. cholerae genome submissions. (A) The origin of V. cholerae producing samples subjected to the next generation sequencing and data sharing over period of the analysis. (B) Temporal trends in relative contributions of genome sequences by academic institutions and public and private microbiology service providers. (C) Upset plot describing patterns of provenance and phenotype data included in the sequence data submissions by academic researchers and microbiology service providers. (D) Box plots per year of submission describing yearly sample collection to genome submission time lags. The red horizontal line is the overall median (i.e. 8 years).

There was also significant variability of data features determining genomic data quality and the availability of key metadata. Only 36% (2,411/6,774) of assemblies submitted by academic institutions and 73% (2,445/3,336) of assemblies submitted by microbiology service providers included raw sequencing data (i.e. linked to entries on the NCBI Sequence Read Archive [SRA]). For academic institutions, the proportion of submissions without appropriate metadata about the source of samples remained relatively large at 62% (4,172/6,774), as did the proportion of sequences missing the year or country of sample origin at 28% (1,890/6,774). This compares to 17% (549/3,336) without sample source and 18% (601/3,336) without year or country of sample origin for microbiology service providers (Fig. 3C). We note that 3,224 of the BioSamples originated from a single academic institution and 1,062 originated from one reference microbiology service provider. Excluding these samples, the fraction missing source information changed to 27% (948/3,550) for academic and 23% (529/2,274) for microbiology service providers, and the fraction missing year or country changed to 22% (784/3,550) for academic and 18% (415/2,274) for microbiology service providers. The time lag between the collection of original samples which eventually produced V. cholerae sequences and the subsequent submission of an assembled genome to an international database for sharing was substantial (i.e. median 8 years) and has not improved over the years. There were also multiple examples when this collection to submission time lag exceeded 50 years (Fig. 3D).

Dissecting aggregated data value

The estimated value of genomic data for V. cholerae in NCBI GenBank has significantly increased in the last fifteen years. Figure 4 outlines key features of this data and shows the upward trend in the annual data value. The value index of aggregated submissions from microbiology service providers i.e. public health and clinical laboratories, appears to be higher than one of submissions from academic institutions (0.24 vs 0.04, respectively, Fig. 4A). While the annual value of genomes submitted by academic institutions remained relatively stable over the study period, the cumulative value of genomes provided by microbiology laboratories gradually increased (Fig. 4B). A large submission from a single academic institution in early 2024 with scarce metadata skewed the profile for that year. High, medium and low value genomes were dispersed across different sequence types of V. cholerae (Fig. 4C).

The aggregated value of V. cholerae genomes. (A) Value distribution and value index (lower right of each panel) with the horizontal scale proportional to number of sequences. Grey vertical lines are quartiles. (B) Temporal trends in the value index of annual submissions of V. cholerae genomes shared by academic institutions and microbiology service providers. (C) Minimum spanning tree representing the network distribution of value. The edges between nodes reflect number of allelic differences between related MLST types. Node sizes are proportional to the number of genomes associated with particular MLST. Edges of less than two allelic differences in length are collapsed and the number of genomes within each category is listed in square brackets.

When we focused on all genomes that could be in silico serotyped as either O1 or O139, similar trends were also observed in this subset (Fig. S3). Sharing of V. cholerae O1/O139 genomes during the current 7th pandemic may however offer more global health value for secondary use than sharing genomes of non-toxigenic strains.

Discussion

With growing demand for representative genomic data for secondary analysis, model validation, and to train AI models, it can be expected that producers of genomic data will take a keen interest in the value they are providing to other users when they decide whether to openly share their datasets. There are incentives to develop and maintain a collaborative environment for collective and responsible data value creation and extraction. However, genomic data is a non-rivalrous good (i.e. easy to copy and difficult to protect), making its value difficult to assess22. There is an acknowledgement that there is no direct correlation between the cost of sequencing and the true value of sequenced genomes. In addition, diminishing returns on investment when more closely related microbial genomes are sequenced from similar locations and points of time have been recognised14. The custodians of ‘raw’ genomic data are often disenfranchised for the international release of their potential assets and there is a risk of unequitable reuse of such data23. Our suggested framework helps to estimate the deferred value of shared microbial genomes and potential benefits for both data providers and recipients. It should assist in identifying high-value cases for genome sequencing and sharing, encourage their timely sharing for further value extraction and recognise the redundant data. It can also serve as an enabler for the urgent and sustained investment in microbial genomics and surveillance to support pandemic preparedness, global health and innovation7.

Importantly, an increasing proportion of microbial genomes are generated by a growing number of microbiology service providers implementing sequencing technologies. This reflects the maturation of the sequencing technologies and bioinformatics pipelines and their expansion from academic settings into diagnostic and public health laboratories. This shift has significant implications for microbial sequencing data sharing and stewardship. While research funded sequencing data are made accessible with publication, there is, in general, no such expectation for data generated by health service providers. These volumes of important but otherwise untapped UJAD data are likely to significantly expand in the coming years.

Both restricted availability of timely data and incompleteness of metadata limit the utility of genomic datasets24,25. It is concerning that the prolonged collection to submission time lag in association with V. cholerae genomes has not much improved since 2010. This is in contrast with 78% reduction in time lag achieved during the COVID-19 pandemic when it moved from a medial time of 85 days in 2020 to 19 days in 2021 based on 7 million SARS-CoV-2 submissions to GISAID by providers in 208 countries26. The scientific community and custodians of sequence databases should encourage provision of the date of sequencing by uploaders, as this information would allow more nuance in interpreting delays between sample collection and sequence sharing. Our study set includes a pandrug-resistant V. cholerae strain isolated from a cholera patient in Bangladesh – an example of a high-value sequence that would be of benefit to others if shared promptly – that was uploaded to GenBank one year after the sampling date, and not formally published until a further year later27. While there is insufficient information to determine why a given sequence was not promptly shared, we suggest that an appropriate measure of deferred value could incentivize greater sharing of such high-value sequences. The mechanism to incentivize sharing might take the form of an evidence-driven argument to funding agencies about the benefit of sharing data openly, or a data marketplace with some amount of compensation whether in a financial or reputational sense. Further work is warranted to develop governance structures that would support these approaches28.

Our example dataset indicated significant under-representation in public databases of relevant pathogen genomes from areas of their endemicity. It resonates with the COVID-19 pandemic experience when over 85% of SARS-CoV-2 genomes in GISAID have been provided by the laboratories from North America, Europe and Australia10. Such significant gaps in genomic data from low and middle-income countries disproportionally affected by epidemic diseases can decrease the aggregated value of genomic data. Genomic data from low-income but high disease prevalence countries may have an intrinsically higher value to the international data users as it would reduce bias in more accessible datasets from high-income low prevalence countries. Sequencing and sharing of archived samples collected before the routine availability of sequencing technologies, as is evidently common with V. cholerae, can enrich genomic datasets when they contribute genomic diversity that is not otherwise present in the dataset or provide historical context for the long-term evolution and genesis of lineages.

These findings reiterated the importance of equitable and timely sharing of sequences with appropriate metadata29. The consensus metadata schema should utilise suitable interoperable ontologies such as the Genomic Epidemiology Ontology (GenEpiO), which was developed according to the principles and practices of the Open Biological and Biomedical Ontology Foundry19,30, as well as other data interoperability standards31. The consensus metadata schema should also capture the key applications, such as public health and drug resistance surveillance, drug and vaccine discovery research, investigation of healthcare transmission events, as well as benchmarking and training of AI models32. The contemporary approach by international databases of accepting sequencing data with only minimal meta-data to overcome the governance barriers can be increasingly counterproductive as it a priori diminishes the value of data and the opportunity for shared value creation. It additionally imposes a significant burden on secondary users of the data to synthesize sources, interpret metadata and seek clarification or elaboration from contributors33. We need systems that can work alongside diverse cultural and legal traditions contributing to differences in health data protection legislation, to facilitate genomic data value creation and extraction, and reward value creators29.

Some limitations of our approach in the valuation of genomic data available to aggregation should be acknowledged. First, we applied a relatively narrow view of genomic data quality focusing primarily on the data accuracy and completeness rather than on data credibility and consistency. The value scores utilised in our exemplar dataset provide only a basic estimation of the non-monetary deferred value of shared microbial genomes irrespective of disease-specific attributes. They are focused on reusability of data and might be applied as the first step to identify genome uploads of potentially high or low value for data aggregation and secondary use including machine learning. Second, the value of genomic data release and aggregation can heavily depend on the application scenario and the stakeholder’s perspective. There could be inherent quality differences between data in user submitted public datasets and carefully curated databases for specific organisms23. The value of the same data in different scenarios can vary and stakeholders may have disparate views on how to measure the success of their data sharing. Further work to characterise secondary applications of sequencing datasets would help to refine important elements of the value score and their weighting. Third, we have explored the domain of V. cholerae sequences within NCBI GenBank. The added value of microbial genomics in other infectious diseases and datasets collated by more specialised databases like PubMLST34 might be different. The subset of assembled genomes employed in our analysis may have a bias towards higher quality submissions. However, we argue that the cholera dataset has provided a representative example reflecting globally relevant trends in data sharing and allowing scalable estimation of the day-after-tomorrow value proposition which will likely shape the value chains of pathogen genomics data for data mining, meta-analyses, collective intelligence and machine learning. We note that our framework does not assess the immediate value of microbial genomics for clinical management, disease surveillance, public health interventions, research, drug development, and other such applications realised by teams organising sequencing experiments.

In conclusion, with the looming risks of new epidemics and increasing value of data driven by advances in AI, the case for promoting and utilizing the deferred value of microbial genomic data is more compelling than ever before. Existing inequalities in genomic data production and analysis should be rebalanced and the collective value creation recognised and adequately supported in order to promote and sustain genomic data sharing. The current mismatch between growing the number of publicly available sequenced genomes and the lack of associated metadata significantly limits the opportunity for extracting deferred value from these genomes in full. The deferred value framework described here intends to incentivise prompt data sharing by maximising the value of sequencing accompanied with appropriate metadata with minimal time lag between sample collection and genome submission. The data value assessment should pave the way for the international mobilization of quality microbial genomic data for global health and knowledge discovery where shared data value creation is appropriately acknowledged and rewarded.

Methods

Data extraction

The NCBI databases were accessed through the Entrez interface using the R package “rentrez” version 1.2.3 (https://docs.ropensci.org/rentrez/). Candidate BioSamples were selected using the organism query “Vibrio cholerae[ORGN]” on the BioSample database, which returned 26,792 matches. The metadata was downloaded on 24 May 2024 and processed with our analysis scripts35. These were discarded unless they had a database link from their BioSample record to the assembly database. 10,110 BioSamples remained after this step and were retained for analysis, as listed in Supplementary Table S1. Genomic assemblies of these 10,110 Vibrio cholerae were downloaded using the NCBI dataset command line tool version 16.11.0 (https://github.com/ncbi/datasets).

Data normalization

The Entrez interface was used to extract all attributes associated with the analysis BioSamples. The attribute names were taken from the “harmonized_name” field to normalize conventions from different source databases. Several non-standard attributes were normalized where appropriate. Where a “sample derived from” attribute existed, any missing sample attributes were filled in from the source sample’s record. When the BioSample owner was recorded as “EBI”, the original owner’s name was taken from the “INSDC center name” attribute. A set of non-standard values denoting missing data (e.g., “Unknown” and “not provided”) were replaced with empty values across all attributes.

All attributes describing owners of the BioSample that appeared in the analysis set were annotated to distinguish between academic institutions (e.g., universities, biomedical research institutes and organizations) and microbiology service providers (e.g., hospital and public health laboratories). The list of all country names appearing in the “geo_loc_name” BioSample attribute in the analysis set was categorized according to cholera endemicity, defined as a reported disease burden in excess of 10 cases per 10,000 population21 (Supplementary Table S6), and membership on the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook advanced economies list (https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2023/April/groups-and-aggregates#ae, Supplementary Table S7). Note that the two categories of countries are mutually exclusive. The R code used to curate the data, and the categorizations of institutions and of countries, are reproduced in our analysis scripts35.

Sequence quality sub-score

The Entrez interface was queried to identify links from BioSamples to the SRA and assembly databases. Where multiple such links existed for a BioSample, the most appropriate entry was determined manually. The reported assembly length was compared to the length of the reference genome Vibrio cholerae strain RFB1636. The reported total base count from SRA was divided by the reference genome length (4,138,412 bases) to obtain the theoretical average sequencing depth. These values were then used to determine the sequence quality sub-score according to Supplementary Table S2, using genome depth recommendations for pathogen categorizations37 and the limits utilized by the genome size check metrics of NCBI GenBank for size assessment.

Contextual metadata sub-score

Metadata items were mapped to specific attribute names from standard upload schema or from freeform values appearing in the analysis dataset. For example, the sample source metadata item was mapped to attributes including “isolation_source” and “host_tissue_sampled”. A metadata item was considered to be provided for a BioSample if at least one of the corresponding attributes had a value. The presence of a link to PubMed was determined by checking for database links from BioSample to PubMed, and from BioProject to PubMed for all BioProjects linked to a given BioSample. These metadata items were then used to compute the contextual metadata sub-score (Supplementary Table S3). The details of this analysis are recorded in the R scripts in supplementary data.

Novelty sub-score

The novelty of sequences was determined by assessing BioProject attributes according to Supplementary Table S4. The “name,” “title,” and “description” attributes were used along with the number of linked BioSamples and the proportion of these that were reported as V. cholerae. Where a BioSample was linked to multiple BioProjects, the highest novelty sub-score was used.

Timeliness sub-score

The timeliness sub-score was computed according to Supplementary Table S5 using the difference between the year of the BioSample submission date and the year of the “collection_date” BioSample attribute.

Value score computation

We defined the deferred value of shared data within a single genome (V) as a function of the sequence quality sub-score (S), novelty sub-score (O), contextual metadata sub-score (M), and the inverse of the timeliness sub-score (T). Each component takes an integer value between 1 and 3, with higher scores for S, O, and M indicating “better” genomes, and lower values for T indicating more timely submissions. We estimated V as

The constant terms adjust the range so that V takes values between zero and one.

Dataset value index computation

The economics approach to scientific data depends on the availability of data value estimates38. The value index (\(\bar{V{\prime} }\)) of a collection of \(N\) genomes represents their aggregated value. It is the average value score of the individual submissions, adjusted by genomic diversity:

The sum term inside the parentheses is the Simpson index of diversity: for each of the R distinct multi-locus sequence types (MLST) in the dataset, nj is the number of sequences with that type. The term in parentheses therefore represents the probability that two sequences drawn from the dataset at random (with replacement) have different sequence types. The value index accordingly penalizes datasets with low genomic diversity.

MLST and in silico serotyping

Multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) was performed on the 10,110 assemblies as input using mlst version 2.23.0 (https://github.com/tseemann/mlst) with default settings and the Vibrio cholerae scheme (--scheme vcholerae). A minimum spanning tree was generated from the allele calls of 10,106 genomes using GrapeTree version 1.5.0 with the MSTree V2 algorithm (https://github.com/achtman-lab/GrapeTree). Four V. cholerae genomes were omitted because they had no MLST allele calls.

Serotypes were inferred from the same genomic assemblies using ABRicate version 1.0.1 (https://github.com/tseemann/abricate) with the CholeraFinder database (https://bitbucket.org/genomicepidemiology/choleraefinder_db). We considered hits only to three nucleotide sequences from this database: the ompW, rfbV-O1 (O1 serogroup specific genes) and wbfZ-O139 (O139 serogroup specific) gene markers. ABRicate was configured to use a minimum DNA identity threshold of 95% and minimum DNA coverage threshold of 60%. Genomes were inferred to be either O1 or O139 if they had a hit for the corresponding serogroup-specific gene, whether or not there was a hit for ompW. Other genomes with only a hit for ompW were inferred to be non-O1/O139 V. cholerae, while genomes with no hits to any of the three markers were undetermined.

Data availability

All tables used to classify the metadata are openly available35.

Code availability

All R code, classification (of countries, institutions, etc.), and instructions to reproduce the metadata analysis are openly available35.

References

World Health Organization. Global genomic surveillance strategy for pathogens with pandemic and epidemic potential 2022–2032. WHO 2022 (2022).

Gardy, J. L. & Loman, N. J. Towards a genomics-informed, real-time, global pathogen surveillance system. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 9–20 (2018).

Black, A., MacCannell, D. R., Sibley, T. R. & Bedford, T. Ten recommendations for supporting open pathogen genomic analysis in public health. Nat. Med. 26, 832–841 (2020).

Chen, Z. et al. Global landscape of SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance and data sharing. Nat. Genet. 54, 499–507 (2022).

Inzaule, S. C. et al. Genomic-informed pathogen surveillance in Africa: Opportunities and challenges. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21(9), e281–e289 (2021).

WHO Guiding principles for pathogen genome data sharing. WHO (2022).

Tosta, S. et al. Global SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance: What we have learned (so far). Infect. Genet. Evol. 108, 105405 (2023).

Brito, A. et al. Global disparities in SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance. Nat. Comm. 13(1), 7003 (2022).

Lenharo, M. ‘Pandemic treaty’: Nations wrestle with sharing virus data. Nature 618, 896–897 (2023).

Enserink, M. & Cohen, J. Control issues. Science 380(6643), 332–339 (2023).

Halabi, S., Wilder, R., Gostin, L. O. & Hurtado, M. L. Sharing pathogen genomic sequence data – Toward effective pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response. New Engl. J. Med. 388, 2401–2404 (2023).

Field, E., Strathearn, M., Boyd-Skinner, C. & Dyda, A. Usefulness of linked data for infectious disease events: A systematic review. Epidemiol. Infect. 151, e46 (2023).

Sintchenko, V. & Coiera, E. The case for including microbial sequences in the electronic health record. Nat. Med. 29(1), 22–25 (2023).

Ladner, J. T. & Sahl, J. W. Towards a post-pandemic future for global pathogen genome sequencing. PLoS Biol. 21(8), e3002225 (2023).

Badal, K., Lee, C. M. & Esserman, L. J. Guiding principles for the responsible development of artificial intelligence tools for healthcare. Comm. Med. 3, 47 (2023).

Liang, W. et al. Advances, challenges and opportunities in creating data for trustworthy AI. Nat. Machine Intell. 4, 669–677 (2022).

Walton, M. G., Cubillejo, I., Nag, D. & Withey, J. H. Advances in cholera research: from molecular biology to public health initiatives. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1178538 (2023).

Hu, D. et al. Origins of the current seventh cholera pandemic. Proc. Natl. Acd. Sci. USA 113(48), E7730–E7739 (2016).

Griffiths, E. J. et al. Future-proofing and maximizing the utility of metadata: the PHA4GE SARS-CoV-2 contextual data specification package. Gigascience. 11, giac003 (2022).

Brown, B. et al. An economic evaluation of the whole genome sequencing source tracking program in the U.S. PLoS One. 16(10), e0258262 (2021).

Ending Cholera: A global roadmap to 2030. Global Task Force on Cholera Control, World Health Organization, (https://www.gtfcc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/gtfcc-ending-cholera-a-global-roadmap-to-2030.pdf) (2017).

Spiekermann, M. Data marketplaces: Trends and monetisation of data goods. Intereconom. 54(4), 208–216 (2019).

Sielemann, K., Hafner, A. & Pucker, B. The reuse of public datasets in the life sciences: Potential risks and rewards. Peer J. 8, e9954 (2020).

Cheung, S. Disambiguating the benefits and risks from public health data in the digital economy. Big Data & Society 7, 1 (2020).

Ling-Hu, T. et al. Challenges and opportunities for global genomic surveillance strategies in the COVID-19 era. Viruses 14(11), 2532 (2022).

Mahanta, U., Saberwal, G. & Sharma, G. Are countries becoming better at SARS-CoV-2 genomics surveillance? Front. Public Health. 10, 887955 (2022).

Kabir, M., Imam, R., Farzana, Z. & Hossain, C. F. Complete genome sequence of the pandrug-resistant Vibrio cholerae strain KBR06 isolated from a cholera patient in Bangladesh. Microbiol. Res. Announc. 12(12), e0057723 (2023).

Holden, N. J. Data sharing considerations to maximize the use of pathogen biological and genomics resources data for public health. J. Appl. Microbiol. 135(9), lxae204 (2024).

Reichman, J., Uhlir, P., Dedeurwaerdere, T. Governing digitally integrated genetic resources, data and literature: Global intellectual property strategies for a redesigned microbial research commons. Cambridge University Press (2016).

GenEpiO Consortium. Genomic Epidemiology Ontology. https://geneepio.org (2025).

Timme, R. E. et al. Optimizing open data to support one health: best practices to ensure interoperability of genomic data from bacterial pathogens. One Health Outlook 2, 1–11 (2020).

Gill, I. S. et al. The DataHarmonizer: A tool for faster data harmonization, validation, aggregation and analysis of pathogen genomics contextual information. Microb. Genom. 9(1), mgen000908 (2023).

Pettengill, J. B. et al. Interpretive labor and the bane of nonstandardized metadata in public health surveillance and food safety. Clin. Infect. Dis. 73(8), 1537–1539 (2021).

Jolley, K. A., Bray, J. E. & Maiden, M. C. J. Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res. 3, 124 (2018).

Sintchenko, V., Sim, E. & Suster, C. Estimating the deferred value of pathogen genomic data for secondary use (Version 2). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15192410 (2025).

NCBI Reference Sequence https://identifiers.org/refseq.gcf:GCF_008369605.1 (2019).

Bogaerts, B. et al. Evaluation of WGS performance for bacterial pathogen characterization with the Illumina technology optimized for time-critical situations. Microb. Genom. 7(11), 000699 (2021).

Wible, J. R. The economics of science: Methodology and epistemology as if economics really mattered (Routledge, 1998).

Aggarwal, A. et al. Platform for isolation and characterization of SARS-CoV-2 variants enables rapid characterization of Omicron in Australia. Nat. Microbiol. 7, 896–908 (2022).

Rockett, R. J. et al. Genomic surveillance enables suitability assessment of Salmonella gene targets used for culture-independent diagnostic testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 58(9), e00038-20 (2020).

Rockett, R. J. et al. Revealing COVID-19 transmission in Australia by SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencing and agent-based modelling. Nat. Med. 26(9), 1398–1404 (2020).

Mason, L. et al. The evolution and international spread of extensively drug resistant Shigella sonnei. Nat. Comm. 14(1), 1983 (2023).

Shuaib, Y. A. et al. Origin and global expansion of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex lineage 3. Genes 13(6), 990 (2022).

Walker, J. et al. Assessing the global risk of typhoid outbreaks caused by extensively drug resistant Salmonella Typhi. Nat. Comm. 14, 6502 (2023).

Chen, Y., Liu, Q., Takiff, H. E. & Gao, Q. Comprehensive genomic analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveals limited impact of high-fitness genotypes on MDR-TB transmission. J. Infect. 85(1), 49–56 (2022).

Gangavarapu, K. et al. Outbreak.info genomic reports: scalable and dynamic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 variants and mutations. Nat. Meth. 20, 512–522 (2023).

Payne, M. et al. Multilevel genome typing: Genomics-guided scalable resolution typing of microbial pathogens. EuroSurveillance 2020 25(20), 1900519 (2020).

Suster, C. J. E. et al. Guiding the design of SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance by estimating the resolution of outbreak detection. Front. Public Health. 10, 1004201 (2022).

Duchene, S. et al. Assessment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 intervention strategies in the Nordic Countries using genomic epidemiology. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 9(3), ofab665 (2022).

Arnott, A. et al. Documenting elimination of co-circulating COVID-19 clusters using genomics in New South Wales, Australia. BMC Res. Notes 14(1), 415 (2021).

Bortolaia, V. et al. ResFinder 4.0 for predictions of phenotypes from genotypes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 75(12), 3491–3500 (2020).

Walker, T. M. et al. The CRyPTIC Consortium, The Seq&Treat Consortium, Crook DW, Ismail N and Rodwell TC. The 2021 WHO catalogue of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex mutations associated with drug resistance: A new global standard for molecular diagnostics. Lancet Microbe 3(4), e265–e273 (2021).

Fong, W. et al. SABRes: in silico detection of drug resistance conferring mutations in subpopulations of SARS-CoV-2 genomes. BMC Infect. Dis. 23(1), 303 (2023).

Ren, Y. et al. Prediction of antimicrobial resistance based on whole-genome sequencing and machine learning. Bioinform. 38(2), 325–334 (2022).

Green, A. G. et al. A convolutional neural network highlights mutations relevant to antimicrobial resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Comm. 13(1), 3817 (2022).

Ali, M., Nelson, A. R., Lopez, A. L. & Sack, D. A. Updated global burden of cholera in endemic countries. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9(6), e0003832 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This analysis was supported by the Centre for Infectious Diseases and Microbiology-Public Health, funded by the New South Wales Ministry of Health’s Prevention Research Support Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed substantially to this study. Conceptualisation: V.S. Data curation and investigation: C.S., E.S., V.S. Visualisation: C.S., E.S. Writing - original draft: V.S. Writing - review & editing: C.S., E.S., V.S. All authors approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sintchenko, V., Sim, E.M. & Suster, C.J.E. Estimating the deferred value of pathogen genomic data for secondary use. Sci Data 12, 784 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05049-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05049-x