Abstract

Ocean currents are fundamental drivers of marine biodiversity distribution, mediating the exchange of genetic material and individuals between populations. Their effect ranges from creating barriers that foster isolation to facilitating long-distance dispersal, which is crucial for species expansion and resilience in the face of climate change. Despite the significance of oceanographic connectivity, comprehensive global estimates remain elusive, hindering our understanding of species’ dispersal ecology and limiting the development of effective conservation strategies. We present the first dataset of connectivity estimates (including probability of connectivity and travel time) along the world’s coastlines. The dataset is derived from Lagrangian simulations of passive dispersal driven by 21 years of ocean current data and can be combined with species’ biological traits, including seasonality and duration of planktonic dispersal stages. Alongside, we provide coastalNet, an R package designed to streamline access, analysis, and visualization of connectivity estimates. The dataset provides a new benchmark for research in oceanographic connectivity, enabling a deeper exploration of the complex dynamics of coastal marine ecosystems and informing more effective conservation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Oceanographic connectivity driven by ocean currents plays a crucial role in shaping the distribution of marine biodiversity. It mediates the extent to which populations exchange genes and individuals, ranging from the structuring of sharp dispersal barriers that isolate populations and foster the differentiation of biodiversity, to long-distance dispersal events that enable the initial settlement and range expansion of species1,2,3. Accordingly, oceanographic connectivity can facilitate the persistence of marine species in the face of climate change by promoting recolonization events and improving resilience through the maintenance of genetic diversity and adaptive potential4,5. Most marine species disperse during their planktonic life stage, with durations varying widely from a few hours to hundreds of days6,7. This variability further influences population connectivity, determining whether populations exist as isolated units or as part of larger, interconnected metapopulations that promote the persistence of extensive regional pools of biodiversity6,7,8,9.

Oceanographic connectivity has not been well resolved at the global scale. Traditional studies often rely on simplified approaches, such as isolation by distance models or broad-scale visualizations of ocean currents10,11, both of which overlook key oceanographic processes (e.g., gyres, tides, eddies) and topographic features that shape complex, asymmetric and highly variable connectivity patterns between populations12,13. Moreover, the relationship between ocean currents and population connectivity unfolds in a non-linear, skewed way2, mirroring the extensive genetic structure found across marine species distributions14,15. Advancements demand biophysical models that integrate Lagrangian simulations with high-resolution oceanographic data (e.g., daily current velocities) and key biological characteristics and constraints affecting marine species (e.g., seasonality and duration of planktonic dispersal events) to accurately predict dispersal pathways between populations and final settlement locations9,16,17,18. Importantly, when coupled with graph theory – where networks are represented as nodes (e.g., coastal sites or biological populations) connected by edges (oceanographic dispersal pathways between nodes) – biophysical models can yield estimates of connectivity that mirror the observed patterns of marine biodiversity, from demography to genetics2,15,19,20,21. In this framework, connections between remote sites, not reachable within a single generation, can be computed as stepping-stone connectivity13. This allows for the estimation of connectivity along various pathways across multiple generations, where each step covers a certain distance. The accumulation of these steps allows one to infer connections over distances otherwise impossible within a single dispersal event.

Despite advancements in biophysical modelling, which have shed light on the drivers of marine biodiversity2,15,19,22 as well as their conservation and management implications7,16,23, progress remains constrained by the lack of a globally accessible, ready-to-use marine connectivity database. This limitation is impaired by the technical and computational requirements associated with the development and running of such complex models. To fill this critical data gap and open new research opportunities, we provide a comprehensive dataset with estimates of connectivity along the world’s coastlines24 - areas of critical importance due to their exceptional marine biodiversity24. These data are derived from a previously validated biophysical model2,12,14,15,20,21,25 that combines Lagrangian simulations of passive dispersal driven by ocean current data with species’ biological traits, including seasonality and duration of planktonic dispersal stages. The dataset is now publicly available, accompanied by coastalNet, an R package designed to streamline access, analysis, and visualization of coastal connectivity estimates. Our contributions, adhering to the FAIR principles of Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability, set a new benchmark for research in oceanographic connectivity, facilitating a deeper exploration of the intricate dynamics of coastal marine ecosystems.

Methods

The dataset of coastal oceanographic connectivity was generated using Lagrangian simulations of passive dispersal that run globally with daily ocean current data from the Global Ocean Physics Reanalysis (GLORYS12V126, https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00021), provided by the EU Copernicus Marine Service (https://marine.copernicus.eu). GLORYS12V1 is a reanalysis of the global ocean at 0.08° horizontal resolution (approx. 9.2 km at the equator) that integrates satellite and in-situ observations from the Coriolis Ocean database for ReAnalysis (CORA) and is forced by the ERA-Interim and ERA5 atmospheric reanalyses27.

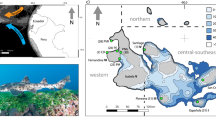

The Lagrangian simulations were performed using R computing language based on a previously validated biophysical model2,12,14,15,20,21,25, which allows for data management, particle tracking, and the processing and recording of connectivity events. The simulations used a virtual spatial environment resolved with the Uber H3 grid system28 at resolution 5, which provides adjacent, equal-area hexagons with a side length of 9.85 km. The grid provides consistent global coverage, and hexagons that intersected the coastline were selected to define coastal source and sink sites for the simulations (Fig. 1). Each coastal site was assigned a unique identifier (ID).

Lagrangian passive particles were released daily from the center of each coastal site over the 21-year period from 2000 to 2020. These particles were advected horizontally by the surface layer of the GLORYS12V1 velocity fields, and their position was tracked hourly through bilinear interpolation, adhering to the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy condition. Particles were allowed to drift for a maximum of 180 days, a period that encompasses the planktonic phase of most marine species7,16. Each time a particle reached a coastal sink site, a connectivity event was recorded. Particles that exceeded the 180-day dispersal period were considered terminated/lost at sea, with no connectivity event recorded for those instances. Releasing one particle per day from each of the 26,642 coastal sites over the 21-year period (365 days per year, including leap years) resulted in 7,670 particles per site, for a total of 204,344,140 particles. Of these, 195,121,399 resulted in recorded pairwise connectivity events. Given the daily resolution of the ocean current data, increasing the number of particles per day would have led to redundant dispersal pathways (please refer to technical validation section), as no artificial stochastic elements (e.g., random walks3,29) were introduced in the simulations.

The dataset generated from these simulations was structured into a GeoPackage (.gpkg) file, which stored the spatial distribution of coastal hexagons, and a comma-separated values (.csv) file, which recorded all connectivity events between coastal sites.

Alongside the dataset, we provide coastalNet, an R package designed to streamline access, analysis, and visualization of connectivity estimates. Within the package, the dataset of connectivity is used to resolve pairwise matrices of connectivity between sites, either as probability or travel time. Specifically, forward probability (also referred to out-degree probability) is determined by dividing the number of particles exchanged between site i and site j, by the total number of particles released by site i2,7,19. Similarly, backward probability (also referred to in-degree probability) is determined by dividing the number of particles received at site i from site j, by the total number of particles received at site i30. These probability values help quantify the strength and directionality of connectivity between different coastal regions. Forward and backward time estimates31 are calculated as the average travel time of particles between sites i and j, and sites j and i, respectively. Additionally, to estimate asymmetrical multigeneration stepping-stone connectivity, which involves a cumulative connectivity pathway for distances covered by populations dispersing across multiple generations, the package integrates a graph-theoretical approach. The term “asymmetrical” refers to the fact that ocean currents often create directional dispersal patterns, meaning that the probability of connectivity from site i to site j might not be the same as the probability of connectivity in the reverse direction. To this end, the graph nodes are defined by the hexagon sites while the edges between them are defined by the corresponding oceanographic connectivity9,32, i.e., forward or backward probabilities, or time-based estimates. The Dijkstra algorithm is used to find the shortest path between sites, by minimizing the sum of log-transformed distances33. In the case of probability-based connectivity, multigenerational connectivity estimates are obtained by multiplying the probabilities along the shortest path, while for time-based connectivity, estimates are calculated as the sum of travel times along the path. In this process, the number of stepping-stone sites involved in each path is determined, providing further insights into the multigenerational dispersal process.

Data Records

The dataset24 of coastal oceanographic connectivity is permanently available for download in a Figshare repository at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25533367. It encompasses two components: (1) a GeoPackage file (referencePolygons.gpkg) designed for geographic information systems (GIS), containing the spatial distribution of the hexagon-shaped coastal sites, each with a unique identifier (ID), and (2) a comma-separated values compressed file (oceanographicConnectivity.csv.zip) containing a matrix detailing the realized connections between pairs of sites. This matrix includes information on the source site (ID), sink site (ID), date of particle release (day, month, year), and the corresponding travel time expressed in days.

The range of oceanographic connectivity probabilities in the dataset is influenced by both direct connections and multigenerational stepping-stone pathways. For direct connections, the lowest possible probability is determined by the smallest number of particles successfully reaching a destination from a given source (i.e., 1 out of 7,670 particles released over 21 years, corresponding to 1.304·10−4 probability). When stepping-stone connectivity is considered, where probabilities are multiplied along the shortest path between multiple sites, the resulting probabilities can be much lower due to the compounding effect of multiple low-probability connections.

Technical Validation

We undertook a set of technical validation steps to ensure the reliability of the Lagrangian simulations.

Data completeness: We checked the daily GLORYS12V1 ocean current data to confirm the absence of missing values. No missing information was resolved, ensuring the integrity and completeness of the input data used in the simulations.

Simulation consistency: We verified that every hexagon site included in the simulations had at least one recorded connectivity event. This step confirmed that all sites were actively participating in the dispersal process, ensuring that no areas were artificially excluded from the connectivity analyses.

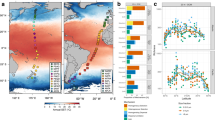

Validation of essential dispersal dynamics: We verified that the resolved connectivity reflects expected patterns of advected particle movement under Lagrangian dynamics2,25,34. This step, considering both the number of realized connectivity events and the distance between them, confirmed that (1) longer particle durations resulted in higher connectivity between pairs of sites and (2) long-distance dispersal events occur less frequently than shorter ones (Fig. 2a–h)2,25,34.

Metrics of oceanographic connectivity across a range of planktonic durations. (a) Relationship between the number of connections among sites and propagule duration. (b) Relationship between the average connectivity distance among sites and propagule duration. (c–h) Frequency distribution of connectivity distances for different planktonic durations. The vertical dashed lines depict the distances at which 99% of connectivity events are performed.

Sensitivity analysis of particle release frequency: We conducted a sensitivity analysis to evaluate the impact of different particle release frequencies on the resulting coastal oceanographic connectivity estimates. We systematically varied the number of particles released per day, ranging from 24 particles per day (corresponding to one particle released per hour, matching our simulation’s hourly time step) down to a fraction of a particle per day (specifically, 24, 12, 8, 6, 4, 3, 2, 1, and 1/2, 1/3, 1/4,…, 1/75 particles per day). The simulation environment of the sensitivity analysis encompassed the Mediterranean Sea and the adjacent Atlantic Ocean (longitude: −27° to 44°, latitude: 27° to 48°). This configuration resulted in 1,436 source and sink sites, and a maximum of 2,584,800 tracked particles. For each particle release frequency, we calculated the forward probability of connectivity (also referred to out-degree probability) between all pairs of coastal sites. We then compared the resulting connectivity matrices to a reference scenario using the maximum frequency of 24 particles per day by calculating the Pearson’s correlation coefficient, the mean absolute difference, and Cohen’s d. Considering our established frequency of 1 particle per day, we found a very high Pearson’s correlation of 0.997, a mean absolute difference in connectivity probabilities of 0.010, and a Cohen’s d of 0.005, indicating a negligible difference in mean probabilities (Fig. 3). Furthermore, a linear model comparing the paired connectivity estimates from the 24-particle and 1-particle-per-day scenarios revealed a highly significant (p < 2.2e-16) and remarkably strong linear relationship, closely approaching a 1:1 correspondence (R-squared = 0.999; Fig. 3). This analysis shows that, given the daily resolution of the underlying GLORYS12V1 ocean current data, increasing the number of particles released per day beyond one leads to redundant trajectories at the scale of our analysis without substantially altering the overall connectivity patterns. Conversely, reducing the number of particles per day below one can potentially impact the resolved global coastal connectivity patterns (Fig. 3).

Sensitivity analysis of particle release frequency. (a) Pearson’s correlation coefficient, (b) mean absolute difference in connectivity probability, and (c) Cohen’s d, comparing connectivity matrices derived from simulations with varying numbers of particles released per day (from 1/75 to 24) to a reference simulation with 24 particles released per day (corresponding to one particle released per hour, matching our simulation’s hourly time step). The vertical dashed line and the red dot indicate the original configuration of 1 particle per day. (d) Scatter plot comparing pairwise connectivity probabilities estimated with 24 particles per day versus 1 particle per day.

While the simulations are based on robust, extensively validated oceanographic reanalysis fields from the GLORYS12V135,36,37, it is important to note that tidal dynamics are not explicitly addressed, and some localized processes like along-shore and cross-shore velocities have not been thoroughly documented. As a result, users should be aware of potential limitations in the applicability of the dataset in coastal regions subject to strong tidal currents38,39. Supplementary models or region-specific analyses in areas of strong tidal currents can aid in enhancing the accuracy of connectivity patterns. Additionally, the use of a hexagonal grid simplifies coastal topography, which may reduce spatial precision in highly complex coastal regions. These limitations are not unique to our dataset and are common challenges in global-scale environmental modeling and remote sensing, where balancing spatial resolution with global coverage often requires compromises, particularly when it comes to resolving fine-scale oceanographic and geographic processes.

Usage Notes

Users have two primary options for utilizing the dataset: they can either work directly with the geospatial vector for GIS, paired with the corresponding matrix of realized connections, to retrieve pairwise connectivity estimates between coastal sites globally, or they can use the coastalNet R package for streamlined access and analysis.

For users opting to work within a GIS environment, the geospatial vector file contains the spatial distribution of the coastal hexagons, each identified by a unique ID. By identifying the source and sink sites of interest within the spatial data, users can retrieve the corresponding hexagon ID(s). These ID(s) can then be cross-referenced with the matrix of realized connectivity events, which includes information on particle release date, source ID, sink ID, and travel time. This allows users to easily extract the specific connectivity events between selected sites, providing a flexible and detailed approach to analyzing connectivity patterns.

For users opting to work within R, the coastalNet package can facilitate the use of the provided dataset. The package offers a comprehensive suite of functions for accessing, analyzing, and visualizing connectivity data (refer to Table 1 for the list of functions). The getDataBase function retrieves the full database of connectivity events between hexagon sites. Users can specify a region of interest with the getHexagonID function, using various spatial formats (e.g., polygons, raster layers). The getConnectivityEvents function filters the database by region, particle release periods (e.g., species’ spawning periods), and durations. This filtered data can then be processed through the calculatePairwiseConnectivity function to generate connectivity matrices between sites, either as direct connections or through multigenerational stepping-stone pathways based on forward or backward probabilities and travel time. Lastly, the mapConnectivity function allows users to visualize connectivity patterns on maps, offering an easy-to-interpret representation of the data. Code examples showcasing the use of the coastalNet package in various contexts are permanently accessible at https://github.com/jorgeassis/coastalNet.

In both GIS and R approaches, users can use their own species-specific planktonic duration (up to 180 days), ensuring the connectivity estimates align with the biological characteristics of target species7,16. For instance, while studying a fish species with a typical larval duration of 32 days7, users can filter the dataset to solely consider connectivity events of simulated larvae transported within that timeframe. Similarly, users can refine analyses by selecting specific particle releasing periods (months, days, and/or years) to account for the seasonality of dispersal processes or capture the inherent variability in oceanographic connectivity over time12,14,40,41. This flexibility in defining species-specific life history traits enables a nuanced understanding of how ocean currents shape population connectivity across diverse marine species.

Code availability

The code used to develop the dataset24 is permanently available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25533367. The coastalNet R package, along with a set of examples showcasing the diverse applications of the dataset, is permanently accessible at https://github.com/jorgeassis/coastalNet.

References

Manel, S., Boulanger, E., Benestan, L., Mouillot, D. & Dalongeville, A. Revisiting long-distance dispersal in a coastal marine fish. Ecography 2023 (2023).

Gouvêa, L. P. et al. Oceanographic connectivity explains the intra-specific diversity of mangrove forests at global scales. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120 (2023).

Van der Stocken, T., Carroll, D., Menemenlis, D., Simard, M. & Koedam, N. Global-scale dispersal and connectivity in mangroves. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116 (2019).

Razgour, O. et al. Considering adaptive genetic variation in climate change vulnerability assessment reduces species range loss projections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116 (2019).

Molinos, J., Burrows, M. T. & Poloczanska, E. S. Ocean currents modify the coupling between climate change and biogeographical shifts. Sci Rep 7, 1–9 (2017).

Treml, E. A. et al. Reproductive output and duration of the pelagic larval stage determine seascape-wide connectivity of marine populations. in Integrative and Comparative Biology 52, 525–537 (2012).

Assis, J. et al. Weak biodiversity connectivity in the European network of no-take marine protected areas. Science of the Total Environment 773, 1–24 (2021).

Carson, H. S., Levin, L. A., Cook, G. S. & López-Duarte, P. C. Evaluating the importance of demographic connectivity in a marine metapopulation. Ecology 92 (2011).

Rossi, V., Ser-Giacomi, E., Lõpez, C. & Hernández-García, E. Hydrodynamic provinces and oceanic connectivity from a transport network help designing marine reserves. Geophys Res Lett 41 (2014).

Wee, A. K. S. et al. Oceanic currents, not land masses, maintain the genetic structure of the mangrove Rhizophora mucronata Lam. (Rhizophoraceae) in Southeast Asia. J Biogeogr 41 (2014).

Alberto, F. et al. Habitat continuity and geographic distance predict population genetic differentiation in giant kelp. Ecology 91 49–56 (2010).

Klein, M. et al. High Interannual Variability in Connectivity and Genetic Pool of a Temperate Clingfish Matches Oceanographic Transport Predictions. PLoS One 11, e0165881 (2016).

Buonomo, R. et al. Habitat continuity and stepping-stone oceanographic distances explain population genetic connectivity of the brown alga Cystoseira amentacea. Mol Ecol 26, 766–870 (2016).

Abecasis, D. et al. Multidisciplinary estimates of connectivity and population structure suggest the use of multiple units for the conservation and management of meagre, Argyrosomus regius. Sci Rep 14, 873 (2024).

Assis, J. et al. Ocean currents shape the genetic structure of a kelp in southwestern Africa. J Biogeogr 01, 1–14 (2022).

Assis, J. et al. Potential Biodiversity Connectivity in the Network of Marine Protected Areas in Western Africa. Front Mar Sci 8, 1749 (2021).

Lett, C. et al. A Lagrangian tool for modelling ichthyoplankton dynamics. Environmental Modelling and Software 23, 1210–1214 (2008).

Froyland, G., Stuart, R. M. & van Sebille, E. How well-connected is the surface of the global ocean? Chaos 24 (2014).

Assis, J. et al. Past climate changes and strong oceanographic barriers structured low ‐ latitude genetic relics for the golden kelp Laminaria ochroleuca. J Biogeogr 45, 2326–2336 (2018).

Cunha, R. L. et al. Drivers of Cape Verde archipelagic endemism in keyhole limpets. Sci Rep 41817 https://doi.org/10.1038/srep41817 (2017).

Assis, J. et al. Oceanographic Conditions Limit the Spread of a Marine Invader along Southern African Shores. PLoS One 10, e0128124 (2015).

Saint-Amand, A., Lambrechts, J. & Hanert, E. Biophysical models resolution affects coral connectivity estimates. Sci Rep 13 (2023).

Abecasis, D., Fragkopoulou, E., Claro, B. & Assis, J. Biophysical modelling and graph theory identify key connectivity hubs in the Mediterranean marine reserve network. Front Mar Sci 9 (2023).

Assis, J. coastalNet, Global estimates of coastal oceanographic connectivity [dataset]. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25533367 (2024).

Legrand, T. et al. Unravelling the role of oceanographic connectivity in the distribution of genetic diversity of marine forests at the global scale. Global Ecology and Biogeography https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.13857 (2024).

European Union-Copernicus Marine Service. Global Ocean Physics Reanalysis [Data set]. Mercator Ocean International. https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00021 (2024).

Szekely, T., Gourrion, J., Pouliquen, S. & Carval, T. CORA: Coriolis Ocean database for ReAnalysis. SEANOE 29 (2023).

Uber Technologies Inc. H3: Uber's Hexagonal Hierarchical Spatial Index. https://eng.uber.com/h3 Accessed: 2024-01-01.

Ramesh, N., Rising, J. A. & Oremus, K. L. The small world of global marine fisheries: The cross-boundary consequences of larval dispersal. Science (1979) 364, 1192–1196 (2019).

Legrand, T. et al. Spatial coalescent connectivity through multi-generation dispersal modelling predicts gene flow across marine phyla. Nat Commun 13, 5861 (2022).

Froyland, G., Padberg, K., England, M. H. & Treguier, A. M. Detection of coherent oceanic structures via transfer operators. Phys Rev Lett 98 (2007).

Ser-Giacomi, E., Vasile, R., Hernández-García, E. & López, C. Most probable paths in temporal weighted networks: An application to ocean transport. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys 92 (2015).

Dijkstra, E. W. A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. Numer Math (Heidelb) 1 (1959).

Van der Stocken, T., Carroll, D., Menemenlis, D., Simard, M. & Koedam, N. Global-scale dispersal and connectivity in mangroves. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, 201812470 (2018).

Verezemskaya, P. et al. Assessing Eddying (1/12°) Ocean Reanalysis GLORYS12 Using the 14-yr Instrumental Record From 59.5°N Section in the Atlantic. J Geophys Res Oceans 126 (2021).

Fragkopoulou, E. et al. Marine biodiversity exposed to prolonged and intense subsurface heatwaves. Nat Clim Chang https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01790-6 (2023).

Artana, C. et al. The Malvinas Current at the Confluence With the Brazil Current: Inferences From 25 Years of Mercator Ocean Reanalysis. J Geophys Res Oceans 124 (2019).

Lyard, F. H., Allain, D. J., Cancet, M., Carrère, L. & Picot, N. FES2014 global ocean tide atlas: Design and performance. Ocean Science 17 (2021).

Jean-Michel, L. et al. The Copernicus Global 1/12° Oceanic and Sea Ice GLORYS12 Reanalysis. Front Earth Sci (Lausanne) 9 (2021).

Ntuli, N. N. et al. Rejection of the genetic implications of the “Abundant Centre Hypothesis” in marine mussels. Sci Rep 10, 1–12 (2020).

Andrello, M. et al. Low Connectivity between Mediterranean Marine Protected Areas: A Biophysical Modeling Approach for the Dusky Grouper Epinephelus marginatus. PLoS One 8, e68564 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Horizon Europe Framework Programme through project MPAEurope (HORIZON-CL6-2021-BIODIV-01-12) and by the Portuguese National Funds from FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology through projects UIDB/04326/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04326/2020), UIDP/04326/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDP/04326/2020), LA/P/0101/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0101/2020), PTDC/BIA-CBI/6515/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/PTDC/BIA-CBI/6515/2020), the EU BiodivRestore-253 (FCT: DivRestore/0013/2020), the Individual Call to Scientific Employment Stimulus 2022.00861.CEECIND/CP1729/CT0003 (https://doi.org/10.54499/2022.00861.CEECIND/CP1729/CT0003) and the fellowship SFRH/BD/144878/2019 (https://doi.org/10.54499/SFRH/BD/144878/2019). MBA also benefited from support while visiting the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) through the Theoretical Sciences Visiting Program (TSVP) and the research agreement between the MNCN and the Ministry for the Ecological Transition and Demographic Challenge (MITECO) No 20233TE007. The authors acknowledge the Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service (https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/products).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A. coordinated and produced the dataset, developed the biophysical model and the package code, and wrote the original draft. E.F. co-wrote the original draft. E.S. and M.B.A. supervised all phases of dataset production and article writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Assis, J., Fragkopoulou, E., Serrão, E.A. et al. Coastal oceanographic connectivity at the global scale: a dataset of pairwise probabilities and travel times derived from biophysical modeling. Sci Data 12, 737 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05060-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05060-2