Abstract

Large collections of archaeological spatiotemporal data can reveal past cultural and demographic trends, land use strategies, and processes of environmental adaptation. Within Africa, archaeological Big Data can contribute to the study of the spread of agriculture, domesticated species, and specific artefacts and technologies, as well as their ecological impacts. Although reviews addressing these topics are available for different parts of the continent, existing mid-late Holocene archaeology datasets have yet to be compiled into a central, open-access, standardized informatic-oriented dataset. Here we present Wanyika, a dataset of scientific dates from archaeological sites in eastern Africa spanning almost 7 millennia, from ~5000 BCE to 1800 CE. This dataset compiles published scientific dates and associated botanical, faunal, iron, and ceramic finds from sites in Kenya, Tanzania, the Comoros Islands, and Madagascar. The records also include data for megafauna extinctions in Madagascar. We describe the spatiotemporal coverage of the dataset, how the data were collected, the structure of the dataset, and the applied quality control measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite its importance in major models of human demographic and linguistic expansion, agricultural spread, and Indian Ocean trade, the Holocene archaeological record of eastern Africa remains largely unsynthesized and a source of significant debate1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Effectively addressing major archaeological questions, such as whether late Holocene changes in the archaeological record of eastern Africa reflect climate-driven migrations of different human populations, and applying archaeological information to contemporary socio-environmental challenges, especially using new archaeoinformatics approaches, requires the compilation of existing datasets on past human-environment interactions2,9,10,11,12,13. As it stands, much of the relevant archaeological information on eastern Africa’s past is dispersed across publications of varying accessibility, precluding or inhibiting the kinds of analyses that are currently being applied in other regions, and that can shed light on key research questions and debates9,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23.

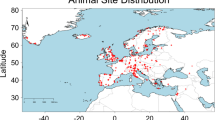

Since the early 20th century, there has been significant growth in available archaeological data for the mid-to-late Holocene in eastern Africa24,25,26,27,28,29,30. These data are the outcome of the application of a variety of approaches, including excavation and survey, as well as archaeobotanical, zooarchaeological, geoarchaeological, isotopic, palaeoproteomic, coring, and remote sensing methods30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. However, available records have yet to be compiled into a standardized dataset format. Here, we present Wanyika43, a dataset of scientific dates and associated archaeological records from mid-late Holocene sites covering four countries (plus a selection of sites in Rwanda) in eastern Africa (Fig. 1). The dataset focuses on these four countries as they possess some of the best documented archaeological records in eastern Africa for this time period, in particular as a result of the application of radiocarbon dating. Wanyika43 is an informatics-oriented dataset that draws together data spanning almost seven millennia, from 5000 BCE to 1800 CE. The Bantu term ‘Wanyika’ translates as “people of the wilderness” and is used to refer to all inland ethnic groups of eastern Africa, as well as those that migrated to the littoral islands and Madagascar44,45,46. The associated archaeological records include spatiotemporal data pertaining to botanical, faunal, iron, and ceramic finds from published archaeological sites, in addition to several unpublished sites, across key regions of mainland and island eastern Africa. We have included iron and ceramic finds because they are closely—although not exclusively—associated with the spread of food production in eastern Africa3,5,27,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65. Ceramic finds are vital because the ceramic styles of hunter-gatherers, pastoralists, and farmers are different1,5,47,51,52,58,60,62,64,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79. Records for megafaunal persistence and coexistence with humans in Madagascar are also included30,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108. Rather than a comprehensive overview, the Wanyika dataset is a preliminary work that serves as a foundation for future research.

Maps of eastern Africa highlighting the disparities in spatial distribution of scientific dates by (a) country and (b) scientific dating technique (14C, OSL and IRSL, TL, and OH); and distribution of dates based on the four quality control measures: (c) stratigraphic integrity and reliability, (d) 14C dates from plant material, (e) 14C dates from faunal material, and (f) 14C dates accuracy in pre-treatment procedure. Note: Class A dates are the most reliable. We used QGIS version 3.28.9545, Natural Earth546, CSV data files547, Adobe Photoshop548, Inkscape app549, to generate Fig. 1 maps.

Archaeology in eastern Africa

Eastern Africa’s past is marked by significant transformations in economic organization, food production, trade, social connections, and climatic conditions5,6,39,40,109,110,111,112,113,114,115. Pastoral communities entered eastern Africa from the north by 4,000 BCE, but pastoralism spread gradually and heterogeneously across the region over the next few thousand years116,117,118. The origins of crop farming are less clear119. While scholars argue that farming may have spread into eastern Africa by 500 BCE, the first evidence for domesticated crops does not appear until the period 300 BCE - 250 CE27,72. Early farmers and herders also relied on hunting and gathering, as well as on trade with Indigenous forager populations5,6,10,25,53,70,120,121,122,123. Eventually, forms of food production involving diverse indigenous crops and exogenous livestock coalesced in eastern Africa before spreading to other parts of the continent26,53,60,124,125,126,127,128. There remain major debates as to the role that the migration of different cultural groups3,30,31,36,63,114,122,129,130,131,132,133 and major changes in climatic and environmental conditions134,135,136,137 played in these processes. During the 1st and 2nd millennia CE, eastern Africa became part of expanding proto-global exchange networks across the Indian Ocean, with crops, animals, spices, material culture and ideas arriving from Southwest Asia, South Asia and Southeast Asia1,26,55,124,138,139,140,141,142,143.

Major research gaps and unresolved issues persist in eastern African archaeology. For example, archaeological research is unevenly distributed across the region60,128. Extensive areas of eastern Africa have seen minimal research, while researchers have only selectively applied archaeological science methods. This means that large swathes of interior eastern Africa lack archaeobotanical evidence for the origin and dispersal of crops, while coastal and island zones have only recently and patchily been investigated5,6,28,64,119,144,145,146,147,148. Furthermore, a significant percentage of excavated sites lack scientific dates1,26,30,57,125,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171. Almost half of the faunal remains recovered from eastern African archaeological sites have not been identified to the species level70,72,73,172,173,174,175,176,177,178, and the potential of residue analysis and micro-CT scanning in ceramic studies, and of digital archaeology more generally, have yet to be fully explored33,41,175,179,180,181,182,183. Meanwhile, debate continues regarding the involvement of pastoralists in the dispersal of sorghum and finger millet to the interior of eastern Africa5,25,59,111,114,119,131,184. Contention also surrounds the spread of livestock, early farming, iron production, and pottery manufacture, particularly to the coast and islands1,53,119,171,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194, and the role of human colonisation and activity in megafaunal extinctions in Madagascar30,83,85,195. In part, this debate stems from unresolved regional chronologies that would otherwise aid understanding of the origin and dispersal of food production in eastern Africa and the spread of iron-working and ceramic traditions, warranting the revisiting and reanalysis of existing datasets30,82,186,187,196.

These deficiencies mean that many research questions in eastern African archaeology cannot at present be adequately addressed. These include questions surrounding the role of diverse populations in the different stages of eastern Africa’s deep-time history, as well as the spread of diverse languages, species, and technologies. Improved datasets are also required to understand the impact of changing land use on local and regional environments and the role of anthropogenic activities in shaping biodiversity30,82,83,87. Disentangling the complex fisher-forager-pastoralist-farmer interactions in various geographical settings also requires improved data62,63,64,68,74,153,187,194,197,198,199,200,201. Here, in order to begin to more systematically address these critical lacunae at the regional scale, we compile the first archaeological dataset of absolute dates along, with associated botanical and faunal remains, and iron and ceramic artefacts. By highlighting existing data gaps, and paving the way for assembling large, regional-scale datasets, we aim to facilitate initiatives aiming to address major research questions in eastern Africa, and to apply past data to current and future challenges.

Methods

Sampling strategy

The Wanyika43 dataset covers sites located in Kenya, Tanzania, Comoros, and Madagascar that date to the period between c. 5,000 BCE and 1,800 CE (Fig. 1). The dataset addresses all scientifically dated sites in these countries, providing details of available dates, as well as information about associated crop, faunal, iron, and ceramic finds. In addition, selected Rwandan sites with early evidence for domesticated crops and iron artefacts are included in light of their importance to the study of farming dispersals in eastern Africa27,47,72,119,184.

The four countries currently covered by the database, which represent an initial sample of the 18 countries that define eastern Africa202,203, were selected because of their significant contributions to understanding past human-environment interactions in this broader region. Compared to the northern and southern regions of eastern Africa, the countries of the coast (Kenya and Tanzania) and islands (Comoros and Madagascar) have well-documented Holocene archaeological records and are at the heart of key archaeological debates surrounding early farming dispersals and biological exchange mediated by long-distance mobility and cross-cultural interaction3,5,8,16,30,32,53,55,70,72,73,74,82,124,131,132,153,195,198,199,200,201,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214. Over the last 25 years, the application of archaeological science approaches in these countries has resulted in the recovery and identification of an increased number of archaeobotanical and zooarchaeological finds to genus or species level, and has also produced significant numbers of chronometric dates and material culture remains7,30,31,33,34,36,37,38,42,53,55,62,63,67,68,70,71,72,74,80,81,82,83,85,87,91,93,96,98,103,117,124,130,144,152,172,174,178,185,186,187,190,191,192,193,195,200,209,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222,223,224,225,226,227,228,229,230,231,232,233,234,235,236,237,238,239,240,241,242,243,244,245,246,247,248,249,250,251,252,253,254,255,256,257,258,259,260,261,262,263,264,265,266,267,268,269,270,271,272.

Rwandan sites have been included in the dataset because they provide some of the earliest documented evidence of domesticated crops in eastern Africa, and also lie within the hypothesized dispersal route of farmers into the interior of eastern Africa16,47,127,207,273,274,275,276,277,278,279. Evidence for the dispersal of crops across interior eastern Africa is limited; apart from eight Rwandan sites, there are only two sites with archaeobotanical records (Kakapel and Deloraine in Kenya) in the interior72,119,184. These Rwandan sites have produced archaeobotanical remains associated with Urewe ceramics and iron, which are critical to the interpretation of archaeological assemblages in the interior of eastern Africa27,47. The Rwandan region is also hypothesized to have served as a gateway and dispersal point for farming communities migrating into the interior of eastern Africa through either the Mount Elgon or Lake Tanganyika region.

Whilst the dataset does not represent the entirety of eastern Africa, we present Wanyika as a foundational repository that provides a systematic framework for future expansion of eastern African archaeological datasets. As a cautionary note to users of the dataset, we have included a limited set of sites (only sites with scientific dates), which biases estimates about the effect sizes in the existing eastern African archaeological data. The selection of sites with scientific dates might lead to misleading inference at a broad spatiotemporal scale about the question of unravelling the complex interactions of farmers, pastoralists, and foragers in different geographical settings in eastern Africa.

Demarcation of country regions and vegetation cover

To facilitate the exploration of geographical patterns in the data (e.g., Table 3), Kenya, Tanzania and Madagascar were sub-divided into smaller sub-regions (‘Country Regions’), e.g., southwestern, northwestern (see Table 1). These divisions are widely used in the archaeological literature1,58,59,61,66,94,112,116,118,153,155,159,187,190,199,204,209,239,280,281,282,283,284,285,286,287,288,289,290,291,292,293,294,295,296,297,298,299,300,301,302,303,304,305,306,307,308,309,310,311,312,313,314,315,316,317,318,319, but have not been formally constrained before using geographical coordinates. The boundaries used in this study were defined as follows. Mainland Kenya is divided into four broadly equal-sized regions demarcated by latitude 0.5° and longitude 37.7°, with the hinterland, coast and islands demarcated as the fifth region. Likewise, mainland Tanzania is divided into four regions using latitude −6° and longitude 35°, with the hinterland, coast and islands demarcated as the fifth region. Madagascar is also divided into four almost equal-sized regions using latitude -19° and longitude 47°. The predominant vegetation cover for each site and region have also been included13,320,321,322,323,324. These are divided into six categories, including forest/wood/grassland mosaic, montane forest, coastal forest mosaic, dry coastal wooded grassland, dry northern wooded grassland, and dry southern wooded grassland.

Data collection and deposition

Data collection followed the workflow summarized in Fig. 2. The authors drew upon more than 500 scientific publications as data sources based on citations in major review articles and other seminal works on the study regions1,5,25,30,53,55,60,82,83,87,111,124,128,131,138. The scientific search engine Google Scholar was employed to locate further articles using a combination of keywords such as specific country/region names, “archaeology”, “scientific dates”, “archaeobotany”, “zooarchaeology”, “iron”, and “ceramics”. The authors also screened all available volumes of Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa (1967 to 2023) in order to collect further scientific dates and information about associated archaeological finds. For just over half of the published dates, the associated assemblage evidence, i.e. archaeobotanical, zooarchaeological and artefactual evidence, was obtained from separately published specialist articles. Where it was necessary to clarify data issues and locate missing publication data, the original publication authors or expert archaeologists working in eastern Africa were consulted. Radiocarbon dating laboratories were also contacted to provide missing details on published dates and dated material. Based on the references given in review articles and other seminal publications, and on discussions with researchers familiar with the study region, we estimate that at least 90% of the published scientific dates and associated archaeological records from the sampled eastern Africa countries are captured in the Wanyika dataset43.

Flow chart summarizing the construction of the Wanyika dataset43.

Upon completion, the Wanyika dataset was deposited in the Pandora data platform. Pandora is a multi-language, web-based, data management platform, where data communities self-manage membership and self-curate data in various formats202.

Scientific dates and calibration

We employ the term “scientific date” to refer to a date that is determined using scientific dating methods to establish the age of an artefact, feature, and/or site. These methods provide a quantifiable measure of time with an associated margin of error. Five types of scientific dating techniques were reported in the publications that were consulted to compile the Wanyika dataset94,144,280,325,326,327,328: radiocarbon dating (14C), optically stimulated luminescence (OSL), infrared stimulated luminescence (IRSL), thermoluminescence (TL), and obsidian hydration (OH) (Fig. 1(b)). Radiocarbon dates are calculated based on the abundance of the 14C isotope in samples (e.g., archaeobotanical remains or collagen extracted from zooarchaeological remains)325,329. Luminescence dating methods such as OSL, IRSL, and TL determine the last time mineral grains were exposed to sunlight or sufficiently high temperatures144,325,328. Finally, OH dating measures obsidian water absorption to determine the age of an object. Although OH dating can be used to determine absolute or relative dates, only absolute dates (which can be summarized in intervals of calendar years, as opposed to just older or younger than280,325) are recorded in the Wanyika dataset. Relative dates based on material culture typologies such as ceramics and beads are also not included in our dataset1,127,277.

The scientific date of each sample appears in three formats: one showing uncalibrated years before present (BP) in two fields expressing the date BP and standard deviation (SD), another showing calibrated calendar years (BCE and CE) in three fields expressing a 95% probability range plus a mean, and finally one showing calibrated years BP also in three fields expressing a 95% probability range plus a mean. The reference year for uncalibrated 14C and OH dates is 1950. For 14C, the uncalibrated or conventional dates are reported so that their calibration can be revised once calibration curves are updated.

In the case of OSL, IRLS, and TL dates, BP is presented here relative to publication year rather than the conventional BP (Before Present, i.e., 1950). We note that this may differ from sample recovery or sample analysis date, which may represent the actual reference year. However, this choice is seldom reported and we do not anticipate a significant offset between the actual reference year and publication date. Luminescence dating techniques were first introduced in the 1960s, setting a highly conservative upper bound for a potential offset between publication year and the unknown reference year of c. 50 years144,325,328,330,331,332,333.

The 14C dates were calibrated using the most recent calibration curves (IntCal20 and SHCal20) and the Bayesian chronological software OxCal v.4.4334,335,336. For samples located to the south of latitude -17° (the southernmost limit of the Intertropical Convergence Zone; ITCZ), only SHCal20 was used in the calibration process. For samples to the north of this latitude, it was necessary to account for the mixing of northern and southern curves along the ITCZ337,338. In these cases, we calibrated radiocarbon measurements using a mixed IntCal20 and SHCal20 curve with an unknown level of mixing (flat prior between 0 and 100 in OxCal).

Radiocarbon calibrations for aquatic samples followed a protocol similar to that described in Goldstein et al.12. Briefly, for marine shells the marine ΔR radiocarbon offset was calculated around each burial location (radius of 100 km) for a ΔR smoothed surface generated using data from the Marine Reservoir Correction dataset339 and the Bayesian model AverageR340,341. Radiocarbon calibration into calendar dates was done using the Bayesian chronological software OxCal v4.4334. To calibrate a single inland shell, found in the vicinity of the Turkana salt lake, an inland ΔR mean value of 250 14C yrs relative the IntCal20 calibration curve335 was used following Beck et al.342 with an assigned uncertainty of ± 100 14C yrs.

As stated previously, for OSL, IRLS, TL, dates, the calibration process consisted of subtracting the reported BP date from the publication year while for OH the reported BP date was subtracted from 195064,117,144,185,270,278,343. The dates were converted into calendar years and reported as a 95% probability calendar range (BCE/CE).

For all methods, and when available, the dataset also includes the description of the dated sample type and the taxonomic identification. Questionable measurements are flagged under a notes field in the dataset records (e.g., when there were discrepancies among different measurements/dating methods or dates did not agree with known chronological boundaries for a cultural layer). Problematic dates often originated from mixed/unclear contexts72,186,187,196.

Quality control

We developed four chronometric quality control criteria for the scientific dates and used them to grade dates in the dataset into classes. The first criterion is based on a combination of stratigraphic integrity and reliability and is applied to all dates in the dataset to grade them into four classes (Class A–D, with A being the most secure and reliable, and D being the least secure and reliable) (Fig. 1 and Tables 2, 3). The other three criteria were only applied to 14C dates and are based on (i) whether the date was obtained on short or long lived plant material (i.e., the potential presence of an old wood effect)337, (ii) the possible presence of an aquatic radiocarbon reservoir effect344, and (iii) the accuracy of the chronometric determination (Fig. 1 and Table 4). In each of these cases, dates were assigned into three classes (Class A–C), again with A being the most reliable and C being the least reliable. A description of how the quality control criteria were applied is provided below.

Stratigraphic integrity and reliability grading

The stratigraphic integrity for each date was evaluated by assigning points to dates based on the following system (Column BI). Six points were given to a date if the authors of the original publication indicated that it was reasonably well associated with its archaeological context (i.e. the stratigraphic integrity was not questioned). Three points were given to a date that was questioned by either the original authors or in a subsequent publication, for example because the date is more recent than that of the overlying context, or older than that of the underlying context, possibly due to bioturbation. Finally, zero points were awarded to a date that had no contextual information, which is recorded as ‘Unreported’ in Column J. Radiocarbon dates on ratite eggshell and dates obtained using obsidian hydration (OH), which have been shown to be unreliable dating methods30,64,280,337,343, were treated as questioned dates and awarded three points, unless they had no context details in which case they were awarded zero points. Notes on the stratigraphic integrity of a date are found in Column BH of the dataset. We did not undertake any evaluation of the stratigraphic integrity of individual dates other that which has been reported in the published literature.

The reliability of a scientific date was evaluated on the basis of its standard deviation (Column N), with six, four, two and zero points assigned to dates with SDs between 0–25, 26–50, 51–100 and 101–650, respectively.

Subsequently, the points assigned to each date for their stratigraphic integrity and reliability were added and divided by two to give a mean score, which was used to generate Class A-D dates with mean scores of 6, 4–5.5, 2–3.5 and 0–1.5, respectively. The application of the grading system produced comparable class qualities (Table 2). Table 3 summarizes the number of dates based on country and region, dating method, and the stratigraphic integrity and reliability quality control grades.

The dataset43 records from Kakapel (Entry IDs 217 to 244), Gogo Falls (Entry IDs 203 to 216) provide good examples of the grading system. Kakapel has 28 dates, 23 of which are Class A and five of which are Class B. The Class B dates are different because they have SDs between 25–50. Gogo Falls has 14 dates, of which none are Class A because all of the dates have SDs above 60. It has eight Class B dates, four Class C dates and two Class D dates. Gogo Falls also provides examples of bioturbation and OH dating challenges (e.g., Entry ID 204, which is an OH date with an SD of 115 and therefore classified as Class D). The process by which ratite eggshell dates were classified are illustrated by examples from Andakatomena and Tony-Velondriake in Madagascar. A radiocarbon date from Andakatomena on Aepyornis eggshell (Entry ID 1124) was considered questionable owing to the use of an unreliable dating method and had an SD of 25 or less, so was classified as Class B. A similar date from Tony-Velondriake, also on Aepyornis eggshell (Entry ID 1120) and with an SD of 25 or less, was classified as Class C owing to its lack of contextual information.

Radiocarbon (14C) date grading

Radiocarbon dates underwent additional chronometric hygiene using three different criteria (Table 4). The first two criteria consider the in-built age of the sample at death, which varies with the type of material selected for dating. In the case of plant materials, age offsets may be present due to the selection of long-lived wood materials, often referred to as ‘the old wood effect’337,345. Dates obtained on taxonomically identified short-lived plant parts (e.g., annual seeds, leaves, twigs) were graded as Class A, dates obtained on taxonomically identified long-lived plant parts were graded as Class B, and dates where the taxonomic identification of plant parts was not reported were graded as Class C (see Column BJ in the dataset).

The second criterion considered the potential for an age offset owing to an aquatic radiocarbon reservoir effect344, caused by the uptake of 14C-depleted carbon by a marine or freshwater organism or the inclusion of such organisms into human or animal diets344,346,347,348 (Column BK). The degree to which aquatic radiocarbon reservoirs affect radiocarbon dates varies depending on local environmental conditions (which can also change over time), as well as variations between species owing to their habitat and dietary preferences349. We took a coarse approach to this problem, assigning samples with a fully terrestrial diet to Class A, aquatic samples to Class B, and samples that have an unreported origin or derive from humans or animals that may have consumed aquatic foods to Class C. A more detailed analysis of the original publications to assess, for example, whether local radiocarbon reservoir offsets were calculated for dates or the likelihood of aquatic diets using stable isotope data was not undertaken.

The third criterion considers the accuracy of a chronological determination based on the pre-treatment method used and its effectiveness at removing inorganic and organic contaminants, which may skew an age determination. Pre-treatment methods were not recorded in the dataset, and indeed, have rarely been reported alongside radiocarbon determinations in the study region. We employed a coarse filter based on the publication date of the assay (Column BL), working with the knowledge that the accuracy of the 14C dating technique for bone organics was refined in 1971, when the Longin collagen extraction method was introduced350, and in 1988, when ultrafiltration was introduced351. It was also around this time that AMS become an increasingly routine technique in radiocarbon dating of bone and charcoal samples329. Dates reported after 1988, as well as those subjected to chromatographic methods (e.g. XAD, amino acid isolation using HPLC), were assigned to Class A, those reported between 1972 and 1988 were assigned to Class B, and those published prior to 1972 were assigned to Class C.

Data Records

The Wanyika dataset43 has 75 fields organized within eight major categories (Table 5). We provide definitions of these 75 column fields below. Wanyika43 is a spatiotemporal, flat-file dataset in which each row of the dataset represents a single scientific date associated with archaeological records. The total number of dataset records is 1792, each associated with one of 422 sites. The presence of domesticated crop, faunal, iron, and/or ceramic finds is marked by “Yes” in the specific cell, while absence is represented by a blank cell.

The dataset is made available in both Excel and CSV formats via the repository Wanyika (https://pandoradata.earth/dataset/wanyika) within the AfriArch data community on the Pandora data platform https://pandoradata.earth/organization/afriarch202. The upload is the peer-reviewed version of the dataset and will remain static.

Definition of column fields

The column fields are identified by alphabet letters, followed by column title and definition of what the column represents.

A - Entry ID: This number represents a row containing the details of a particular date entry.

B - Site ID: This is a database number assigned to a site. Each site has a unique number. All entries from the same site have the same number.

C - Site Name: Refers to the name of the archaeological site.

D - Country: Name of the country where a site is located (Rwanda, Kenya, Tanzania, Comoros, and Madagascar).

E - Country Region: Name of the region where a site is located within a country, defined by administrative boundaries and latitude/longitude. Information on demarcation of country regions is provided in Table 1.

F – Vegetation cover: Describes the dominant vegetation of the site13,320,322,323,352. Includes six categories: Forest/wood/grassland mosaic, montane forest, coastal forest mosaic, dry coastal wooded grassland, dry northern wooded grassland and dry southern wooded grassland.

G - Latitude: Provides the site’s GIS coordinates for the latitude expressed in decimal degrees relative to WGS84353.

H - Longitude: Provides the site’s GIS coordinates for the longitude expressed in decimal degrees relative to WGS84353.

I - Trench/Site Notes: Provides the excavators’ code number details for the excavation trench, unit, square, quadrant, test pit, feature (e.g., burial, furnace, habitation), and any other unique attributes that define a site (e.g., single component or stratified site short/long term occupation).

J - Context: This includes the context number and/or measurement in cm, layer, level, and stratum. Provides details that define time and space, matrix and provenience.

K - Date Type: Indicates the type of scientific dating method used: 14C, OSL, IRSL, TL or OH.

L - Labcode: This is a code number assigned by the host dating laboratory to the sample used to produce a scientific date. Mostly represented by letters and numbers, where letters are the lab designation and the number the unique sample number, for example OXA-14500.

M - Date BP: Uncalibrated date Before Present.

N - Date BP SD: Standard deviation for the uncalibrated date Before Present.

O - Min Chronology (Calibrated BCE/CE): Minimum calibrated date in calendar years (Before Common Era and Common Era).

P - Max Chronology (Calibrated BCE/CE): Maximum calibrated date in calendar years (Before Common Era and Common Era).

Q - Mean Chronology (Calibrated BCE/CE): Mean calibrated date in calendar years (Before Common Era and Common Era), Minimum + Maximum / by 2 (calibrated date in calendar years).

R - Min Chronology (Calibrated BP - 1950): Minimum calibrated date Before Present (1950 minus Min Chronology calibrated BCE/CE).

S - Max Chronology (Calibrated BP - 1950): Maximum calibrated date Before Present (1950 minus Max Chronology calibrated BCE/CE).

T - Mean Chronology (Calibrated BP - 1950): Mean calibrated date Before Present (Minimum + Maximum / by 2 (Calibrated date Before Present).

U - Dated Material: Type of material/sample that was used to produce the date e.g., charcoal, ceramics, bone collagen, etc.

V - Dated Taxon: Provides the lowest order taxonomic group (species, genus, family, order or kingdom) for plant and animal remains (seeds, charred wood, bone/tooth collagen and apatite) used in dating.

W to AP - Archaeobotanical Information: Columns provide archaeobotanical information. A “Yes or blank cell” indicates the presence or absence of a specific crop. Represented African crops include finger millet (Eleusine coracana), pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), cowpea (Vigna unguiculata), hyacinth bean (Lablab purpureus), Fig (Ficus sp.) and baobab (Adansonia digitata); exotic crops include rice (Oryza sativa), wheat (Triticum aestivum), coconut (Cocos nucifera), mung bean (Vigna radiata), pea (Pisum), red date (Ziziphus jujuba), and cotton (Gossypium sp.).

AQ to BB - Zooarchaeological Information: Columns provide zooarchaeological information for wild and pastoral species (but excluding introduced commensals like cat, dog, black rat). A “Yes or blank cell” indicates the presence or absence of a specific faunal taxon. Faunal taxa include wild tetrapods, avian, aquatic, and indeterminate fauna, as well as pastoral animals like bovids, cattle (Bos taurus/indicus), sheep (Ovis aries) and goat (Capra hircus), indeterminate Ovis/Capra, camel (Camelus dromedary), donkey (Equus asinus) and chicken (Gallus gallus). Directly dated remains of extinct megafauna in Madagascar (ratites, lemuroids, reptiles and non-primate mammals) and other translocated fauna (commensals cat, dog, black rat) are only recorded in the “Dated Taxon” column (column U).

BC to BD - Iron Smelting and Use: “Yes or blank cell” represents the presence or absence of evidence for iron smelting and use.

BE - Ceramics: “Yes or blank cell” represents the presence or absence of evidence for ceramics.

BF - Ceramic Phase (Pottery Ware): Lists the name/s of ceramic style/s associated with the row data. These include 25 major ceramic/pottery tradition/wares in eastern Africa listed in Table 6.

BG - Regional Cultural Phase (Eastern Africa): Lists the regional cultural phase represented by the recorded cultural assemblage. These includes, (a) Prehistoric (applicable for Madagascar), LSA (Late Stone Age), PN (Pastoral Neolithic), the latter divided into SPN (Savanna Pastoral Neolithic) and EPN (Elmenteitan Neolithic), PIA (Pastoral Iron Age); and (b) EIA (Early Iron Age), MIA (Middle Iron Age), LIA (Late Iron Age). See Table 6 for the time period and ceramic tradition associated with each regional cultural phase.

BH - General Notes: Provides important notes about the site/date. These include notes that were used for quality control assessment, for example notes on questionable dates and anomalies as a result of bioturbation.

BI - Mean Grade Chrono Hygiene 1 and 2: Refers to stratigraphic integrity grades tabulated from stratigraphic integrity plus standard deviation (SD) mean scores to produce Class A-D dates. See more details in the section on quality control.

BJ - Chrono Hygiene 3: Grade based on the possibility that the 14C date is affected by long life span plant material (long/short). See Table 4

BK - Chrono Hygiene 4: Grade based on the possibility of the dated material being affected by aquatic 14C reservoir. See Table 4

BL - Chrono Hygiene 5: Grade based on the accuracy of chronological determinations (pre-treatment protocol) for 14C dates. See Table 4

BM - Date of Publication: refers to the earliest year in which the date was published. This year is used to calculate the grades for “Chrono Hygiene 5: Accuracy (pre-treatment) C14 dates” and the BP dates for OSL, IRSL, and TL (the primary publications used the year of excavation as ‘the present’, we use the publication year).

BN to BW - References and DOI 1-5: Provides the bibliographic references and Digital Object Identifier (DOI) or the Uniform Resource Locator (URL) for the sources of data.

Technical Validation

The authors retrieved the data recorded in this dataset primarily from peer-reviewed scientific journals, books, dissertations, monographs, and site reports written by established researchers working in eastern Africa. In several cases, data are also included from ongoing projects awaiting publication. Only dates reported in uncalibrated years before present, having standard deviations and laboratory codes, are included in the dataset. We carried out frequent checks throughout our database construction process and a final comprehensive check was completed towards the end of the process to remove duplicate records and other errors. Approximately 20 dates were excluded for lack of uncalibrated dates (reported in BCE/CE only), SD or laboratory code. For example, two dates from Engaruka and Kuumbi Cave (Tanzania) were excluded for lack of standard deviations185,187,258. A unique case that involved four dates from the Serengeti (Tanzania) being published as Takwa dates (Kenya) was noted59,204,354. These dates were also excluded from the dataset. The author of the Takwa report (page 4, first sentence) acknowledges the error354. Personal correspondence with Geochron Laboratories also confirmed that these dates belong to the Serengeti.

Usage Notes

The FAIR data principles promote good data management practices by encouraging scientists to make their datasets ‘findable’, ‘accessible’, ‘interoperable’, and ‘reusable’355. The Wanyika dataset43, as a member of the Afriarch community hosted on the Pandora platform, adopts these principles. The public availability afforded by Pandora’s web presence makes the data findable and enables accessibility. Wanyika43 promotes data reuse by explicating the results of the quality control analysis and by being open to collaborations that can update the dataset as new information becomes available. Ongoing development of the Pandora platform includes Natural Language Model SQL (Standard Query Language) programming that grants interoperability to datasets such as Wanyika43, which furthermore has the potential for integration into semantically interoperable dataset systems such as MAEASaM (Mapping Africa’s Endangered Archaeological Sites and Monuments).

Code availability

We have used four codes to calibrate the 14C dates in OxCal for (1) terrestrial samples between -18° and 6° latitude, (2) terrestrial samples below -18° latitude, (3) marine samples, (4) freshwater samples (only applicable to a sample above 0.5° latitude). These codes are provided below.

Terrestrial samples located between -18° and 6° latitude

Plot(‘terrestrial samples’)

{

Curve(‘IntCal20,‘IntCal20.14c’);

Curve(‘SHCal’,‘SHCal20.14c’);

Mix_Curves(‘Mixed_terrestrial_curves’,‘IntCal20’, ‘SHCal20’,U(0,100));

R_Date(‘LAB_CODE’,14C_MES,14C_UNC);

}

Terrestrial samples below -18° latitude

Plot(‘terrestrial samples’)

{

Curve(‘SHCal’,‘SHCal20.14c’);

R_Date(‘LAB_CODE’,14C_MES,14C_UNC);

}

Marine samples

Plot(marine samples’)

{

Curve(‘Marine20’, ‘Marine20.14c’);

Delta_R(‘LocalMarine’, MARINE_DR, MARINE_DR_UNC);}

R_Date(‘LAB_CODE’,14C_MES,14C_UNC);

}

Freshwater samples (only applicable to a sample above 0.5° latitude

Plot(‘freshwater samples’)

{

Curve(‘IntCal20,‘IntCal20.14c’);

Delta_R(‘LocalFreshwater’, FRESHWATER_DR, FRESHWATER_DR_UNC);}

R_Date(‘LAB_CODE’,14C_MES,14C_UNC);

}

Definition of terms for OxCal code for calibration of radiocarbon measurements

LAB_CODE stands for radiocarbon lab code

14C_MES stands for the uncalibrated radiocarbon measurement in years BP

14C_UNC stands for the 1-sigma error associated to 14C_MES

MARINE_DR stands for local marine ΔR value

MARINE_DR_UNC stands for the 1-sigma error associated to MARINE_DR

FRESHWATER_DR stands for local freshwater ΔR value

FRESHWATER_DR_UNC stands for the 1-sigma error associated to

FRESHWATER_DR

References

Wynne-Jones, S. & Laviolette, A. The Swahili World (Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2018).

Marchant, R. et al. Drivers and trajectories of land cover change in East Africa: Human and environmental interactions from 6000 years ago to present. Earth-Science Reviews 178, 322–378, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.12.010 (2018).

Lane, P. The moving frontier and the transition to food production in Kenya. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 39, 243–264 (2004).

Kusimba, S. B. Hunter–gatherer land use patterns in Later Stone Age East Africa. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 18, 165–200, https://doi.org/10.1006/jaar.1998.0335 (1999).

Ambrose, S. Chronology of the Later Stone Age and food production in East Africa. Journal of Archaeological Science 25, 377–392, https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.1997.0277 (1998).

Peregrine, P. N. & Ember, M. Encyclopaedia of Prehistory Vol. 1 (Kluwer Academic, 2003).

Ashley, C. Z. & Grillo, K. M. Archaeological ceramics from eastern Africa: past approaches and future directions. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 50, 460–480, https://doi.org/10.1080/0067270X.2015.1102939 (2015).

Kusimba, C. & Walz, J. R. Debating the Swahili: Archaeology since 1990 and into the future. Archaeologies https://doi.org/10.1007/s11759-021-09434-x (2021).

Kay, A. U. et al. Diversification, intensification and specialization: changing land use in western Africa from 1800 BC to AD 1500. Journal of World Prehistory 32, 179–228, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10963-019-09131-2 (2019).

Courtney Mustaphi, C. & Marchant, R. A database of radiocarbon dates for palaeoenvironmental research in eastern Africa. Open Quaternary 2, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.5334/oq.22 (2016).

Courtney Mustaphi, C. et al. Integrating evidence of land use and land cover change for land management policy formulation along the Kenya-Tanzania borderlands. Anthropocene 28, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ancene.2019.100228 (2019).

Goldstein, S. et al. Presenting the AfriArch Isotopic Database. Journal of Open Archaeology Data 10, https://doi.org/10.5334/joad.94 (2022).

Iminjili, V. et al. Late Pleistocene to late Holocene palaeoecology and human foraging at Kuumbi Cave, Zanzibar Island. Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology 2, https://doi.org/10.3389/fearc.2023.1080785 (2023).

Bird, D. et al. p3k14c, a synthetic global database of archaeological radiocarbon dates. Scientific Data 9, 27, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01118-7 (2022).

Bird, M. I., Crabtree, S. A., Haig, J., Ulm, S. & Wurster, C. M. A global carbon and nitrogen isotope perspective on modern and ancient human diet. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, e2024642118, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2024642118 (2021).

Russell, T., Silva, F. & Steele, J. Modelling the spread of farming in the Bantu-speaking regions of Africa: an archaeology-based phylogeography. PloS one 9, e87854–e87854, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087854 (2014).

Chaput, M. A. et al. Spatiotemporal distribution of Holocene populations in North America. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 12127–12132, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1505657112 (2015).

Loftus, E., Mitchell, P. J. & Ramsey, C. B. An archaeological radiocarbon database for southern Africa. Antiquity 93, 870–885, https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2019.75 (2019).

Gattiglia, G. Think big about data: Archaeology and the Big Data challenge. Archäologische Informationen 38, https://doi.org/10.11588/ai.2015.1.26155 (2015).

Huggett, J. Is Big Digital Data different? Towards a new archaeological paradigm. Journal of Field Archaeology 45, S8–S17, https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2020.1713281 (2020).

VanValkenburgh, P. & Dufton, J. A. Big Archaeology: Horizons and blindspots. Journal of Field Archaeology 45, S1–S7, https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2020.1714307 (2020).

Djindjian, F. Big data and archaeology Humanities Arts and Society

Kintigh, K. The promise and challenge of archaeological data integration. American Antiquity 71, 567–578, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0002731600039810 (2006).

Leakey, M. Report on the excavations at Hyrax Hill, Nakuru, Kenya Colony, 1937-1938. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 30, 271–409 (1943).

Clark, D. & Brandt, S. A. From Hunters to Farmers: The Causes and Consequences of Food Production in Africa. 21 (University of California Press, 1984).

Helm, R. et al. Exploring agriculture, interaction and trade on the eastern African littoral: preliminary results from Kenya. Azania Archaeological Research in Africa 47, https://doi.org/10.1080/0067270X.2011.647947 (2012).

Giblin, J. & Fuller, D. First and second millennium AD agriculture in Rwanda: archaeobotanical finds and radiocarbon dates from seven sites. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 20, 253–265, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00334-011-0288-0 (2011).

Odner, K. Excavations at Narosura, a stone bowl site in the southern Kenya Highlands. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 7, 25–92, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672707209511557 (1972).

Gramly, R. M. Pastoralists and hunters: recent prehistory in southern Kenya and northern Tanzania PhD thesis, Harvard University (1975).

Pearson, M. P. et al. Pastoralists, Warriors and Colonists: The Archaeology of Southern Madagascar. (Archaeopress, 2010).

Wang, K. et al. Ancient genomes reveal complex patterns of population movement, interaction, and replacement in sub-Saharan Africa. Science Advances 6, eaaz0183, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaz0183 (2020).

Bleasdale, M. et al. Ancient proteins provide evidence of dairy consumption in eastern Africa. Nature Communications 12, 632, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20682-3 (2021).

Grillo, K. M. et al. Molecular and isotopic evidence for milk, meat, and plants in prehistoric eastern African herder food systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 9793–9799, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1920309117 (2020).

Roberts, P. et al. Late Pleistocene to Holocene human palaeoecology in the tropical environments of coastal eastern Africa. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 537, 109438, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.109438 (2020).

Janzen, A. Mobility and herd management strategies of early pastoralists in South Central Kenya PhD thesis, University of California, (2015).

Prendergast, M. E. et al. Ancient DNA reveals a multistep spread of the first herders into sub-Saharan Africa. Science 365, eaaw6275, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw6275 (2019).

Prendergast, M. E. et al. Reconstructing Asian faunal introductions to eastern Africa from multi-proxy biomolecular and archaeological datasets. PLOS ONE 12, e0182565, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182565 (2017).

Prendergast, M. E., Janzen, A., Buckley, M. & Grillo, K. M. Sorting the sheep from the goats in the Pastoral Neolithic: morphological and biomolecular approaches at Luxmanda, Tanzania. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 11, 3047–3062, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-018-0737-0 (2019).

Kiage, L. M. & Liu, K. Late Quaternary paleoenvironmental changes in East Africa: a review of multiproxy evidence from palynology, lake sediments, and associated records. Progress in Physical Geography 30, 633–658, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133306071146 (2006).

Kiage, L. M. & Liu, K.-b Palynological evidence of climate change and land degradation in the Lake Baringo area, Kenya, East Africa, since AD 1650. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 279, 60–72, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2009.05.001 (2009).

Barron, A. et al. Snapshots in time: MicroCT scanning of pottery sherds determines early domestication of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) in East Africa. Journal of Archaeological Science 123, 105259, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2020.105259 (2020).

Le Meillour, L. et al. The name of the game: palaeoproteomics and radiocarbon dates further refine the presence and dispersal of caprines in eastern and southern Africa. Royal Society Open Science 10, 231002, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.231002 (2023).

Iminjili, V. et al. Wanyika: A dataset of scientific dates from archaeological sites in eastern Africa spanning 5000 BCE to 1800 CE. https://doi.org/10.48493/mwsp-e133 (2025).

Werner, A. The Bantu coast tribes of the East African Protectorate. The Journal Of The Royal Anthropological Institute Of Great Britain And Ireland 45, 326–354 (1915).

Hamilton, R. W. Land Tenure among the Bantu Wanyika of East Africa. Journal of the Royal African Society 20, 13–18 (1920).

Morton, R. F. The Shungwaya myth of Miji Kenda origins: a problem of late nineteenth-century Kenya coastal history. International Journal of African Historical Studies 5, 397–423 (1972).

Giblin, J. & Humphris, J. An Urewe burial in Rwanda: Exchange, health, wealth and violence c. AD 400. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 45, 276–297, https://doi.org/10.1080/0067270X.2010.521677 (2010).

Raymaekers, J. & Van Noten, F. Early iron furnaces with ‘bricks’ in Rwanda: Complementary evidence from Mutwarubona. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 21, 65–84, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672708609511368 (1986).

Van Noten, F. The Early Iron Age in the Interlacustrine region: The diffusion of iron technology. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 14, 61–80, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672707909511263 (1979).

Phillipson, D. W. The chronology of the Iron Age in Bantu Africa. The Journal of African History 16, 321–342, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853700014298 (1975).

Collett, D. & Robertshaw, P. Pottery traditions of early pastoral communities in Kenya. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 18, 107–125, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672708309511317 (1983).

Collett, D. P. & Robertshaw, P. T. Early Iron Age and Kansyore Pottery: Finds from Gogo Falls, South Nyanza. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 15, 133–145, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672708009511280 (1980).

Crowther, A., Prendergast, M. E., Fuller, D. Q. & Boivin, N. Subsistence mosaics, forager-farmer interactions, and the transition to food production in eastern Africa. Quaternary International 30, 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2017.01.014 (2018).

Crowther, A. et al. Iron Age agriculture, fishing and trade in the Mafia Archipelago, Tanzania: new evidence from Ukunju Cave. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 49, 21–44, https://doi.org/10.1080/0067270X.2013.878104 (2014).

Crowther, A. et al. Ancient crops provide first archaeological signature of the westward Austronesian expansion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, 6635–6640, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1522714113 (2016).

Collett, D. P. The spread of early iron producing communities in eastern Africa PhD thesis, University of Cambridge (1985).

Wandibba, S. Ancient and modern ceramic traditions in the Lake Victoria Basin of Kenya. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 25, 69–78, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672709009511409 (1990).

Ambrose, S. in Encyclopaedia of Prehistory Vol. 1 (eds Peter N. Peregrine & Melvin Ember) 96 -109 (Kluwer Academic, New York, 2003).

Ambrose, S. Holocene environments and human adaptations in the central Rift Valley, Kenya PhD thesis, University of California, (1984).

Sinclair, P. J. J. Archaeology in eastern Africa: an overview of current chronological issues. The Journal of African History 32, 179–219, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853700025706 (1991).

Lane, P. in Pastoralism in Africa: Past, Present and Future (eds M. Bollig & H-P. Wotzka) 104-144 (Berghahn Books, 2013).

Lane, P., Ashley, C. & Oteyo, G. New dates for Kansyore and Urewe Wares from northern Nyanza, Kenya. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 41, 123–138, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672700609480438 (2006).

Lane, P. et al. The transition to farming in eastern Africa: new faunal and dating evidence from Wadh Lang’o and Usenge, Kenya. Antiquity 81, 62–81, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00094849 (2007).

Robertshaw, P. Gogo Falls. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 26, 63–195, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672709109511425 (1991).

Robertshaw, P. T. in Early Pastoralists of South-western Kenya (ed P.T. Robertshaw) 183-204 (British Institute in Eastern Africa, 1990).

Lane, P. in The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology (eds Peter Mitchell & Paul Lane) 585-601 (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013).

Grillo, K. M., McKeeby, Z. & Hildebrand, E. A. “Nderit Ware” and the origins of pastoralist pottery in eastern Africa. Quaternary International 608-609, 226–242, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2020.06.032 (2022).

Prendergast, M. Kansyore fisher-foragers and transitions to food production in East Africa: The view from Wadh Lang’o, Nyanza Province, Western Kenya. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 45, 83–111, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672700903291765 (2010).

Prendergast, M. in People and Animals in Holocene Africa: Recent Advances in Archaeozoology (eds Helene Jousse & Josephine Lesur) (Africa Magna Verlag, 2011).

Prendergast, M. E. Forager variability and transitions to food production in secondary settings: Kansyore and Pastoral Neolithic economies in East Africa. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 44, 276–277, https://doi.org/10.1080/00671990903052330 (2009).

Prendergast, M. E., Grillo, K. M., Mabulla, A. Z. P. & Wang, H. New dates for Kansyore and Pastoral Neolithic ceramics in the Eyasi Basin, Tanzania. Journal of African Archaeology 12, 89–98 (2014).

Goldstein, S. T. et al. Early agriculture and crop transitions at Kakapel Rockshelter in the Lake Victoria region of eastern Africa. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 291, 20232747, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2023.2747 (2024).

Dale, D. D. An archaeological investigation of the Kansyore, Later Stone Age hunter-gatherers in East Africa PhD thesis, Washington University in Saint Louis., (2007).

Munene, K. Holocene Foragers, Fishers, and Herders of Western Kenya. (Archaopress, 2002).

Onyango-Abuje, J. C. A contribution to the study of the Neolithic in East Africa with particular reference to the Naivasha-Nakuru Basin PhD thesis, University of California, (1977).

Bower, J. The Pastoral Neolithic of East Africa. Journal of World Prehistory 5, 49–82, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00974732 (1991).

Bower, J. R. F. & Nelson, C. M. Early pottery and pastoral cultures of the central Rift Valley, Kenya. Man 13, 554–566, https://doi.org/10.2307/2801248 (1978).

Bower, J. R. F., Nelson, C. M., Waibel, A. F. & Wandibba, S. The University of Massachusetts’ Later Stone Age/Pastoral ‘Neolithic’ comparative study in central Kenya: an overview. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 12, 119–146, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672707709511251 (1977).

Mturi, A. A. The Pastoral Neolithic of West Kilimanjaro. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 21, 53–63, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672708609511367 (1986).

Crowley, B. E. A refined chronology of prehistoric Madagascar and the demise of the megafauna. Quaternary Science Reviews 29, 2591–2603, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.06.030 (2010).

Kistler, L. et al. Comparative and population mitogenomic analyses of Madagascar’s extinct, giant ‘subfossil’ lemurs. Journal of Human Evolution 79, 45–54, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.06.016 (2015).

Douglass, K. et al. A critical review of radiocarbon dates clarifies the human settlement of Madagascar. Quaternary Science Reviews 221, 105878, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.105878 (2019).

Hixon, S. et al. Late Holocene spread of pastoralism coincides with endemic megafaunal extinction on Madagascar. Proc Biol Sci 288, 20211204, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.1204 (2021).

Hixon, S. W. et al. Drought coincided with, but does not explain, Late Holocene megafauna extinctions in SW Madagascar. Climate 9, 138 (2021).

Hixon, S. W. et al. Ecological consequences of a Millennium of introduced dogs on Madagascar. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 9 https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.689559 (2021).

Crowley, B. E. et al. Island-wide aridity did not trigger recent megafaunal extinctions in Madagascar. Ecography 40, 901–912, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.02376 (2017).

Burney, D. A. et al. A chronology for late prehistoric Madagascar. Journal of Human Evolution 47, 25–63, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.05.005 (2004).

MacPhee, R. D. E. & Burney, D. A. Dating of modified femora of extinct dwarf hippopotamus from southern Madagascar: Implications for constraining human colonization and vertebrate extinction events. Journal of Archaeological Science 18, 695–706, https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-4403(91)90030-S (1991).

Burleigh, R., Arnold, E. N. & Westoll, T. S. Age and dietary differences of recently extinct Indian Ocean tortoises (Geochelone s.) revealed by carbon isotope analysis. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences 227, 137–144, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1986.0014 (1986).

Mahe, J. & Sourdat, M. Sur l’extinction des Vertebres subfossiles et l’aridification du climat dans le Sud-Ouest de Madagascar; description des gisements, Datations absolues. Bulletin de la Societe Geologique de France S7-XIV, https://doi.org/10.2113/gssgfbull.S7-XIV.1-5.295 (1972).

Jernvall, J., Wright, P. C., Ravoay, F. L. & Simons, E. L. Report on the finding of subfossils at Ampoza and Ampanihy in southwestern Madagascar. Lemur News, 21–23 (2003).

de Waard, H. & Straka, H. C14-Datierung zweier Torfproben aus Madagaskar. Naturwissenschaften 48, 45–45, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00603409 (1961).

Hansford, J. et al. Early Holocene human presence in Madagascar evidenced by exploitation of avian megafauna. Science Advances 4, eaat6925, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aat6925 (2018).

Wright, H. T. et al. Datation absolue de sites archeologiques du centre de Madagascar: presentation des determinations. Taloha 11, 121–146 (1992).

Wright, H. T. & Fanony, F. The evolution of settlement systems in the Mananara River Valley: archaeological reconnaissance of 1983-1990. TALOHA, 16-64 (1992).

Karanth, K. P., Delefosse, T., Rakotosamimanana, B., Parsons, T. J. & Yoder, A. D. Ancient DNA from giant extinct lemurs confirms single origin of Malagasy primates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102, 5090–5095, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0408354102 (2005).

Burney, D. A. in Natural Change and Human Impacts in Madagascar (eds S.M. Goodman & B.D. Patterson) 142-168 (Smithsonian Press, 1997).

Goodman, S., Raherilalao, M. J. & Muldoon, K. Bird fossils from Ankilitelo Cave: Inference about Holocene environmental changes in Southwestern Madagasca. Zootaxa 3750, 534–548, https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3750.5.6 (2013).

Goodman, S. M. in Proceedings of the 22nd International Ornithological Congress. (eds N. J. Adams & R. H. Slotow) 3071-3083 (BirdLife South Africa).

Goodman, S. M. & Rakotozafy, L. M. A. in Natural Change and Human Impacts in Madagascar (eds S. M. Goodman & B. Patterson) 142-168 (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997).

Rakotozafy, L. M. A. & Goodman, S. M. Contribution à l'étude zooarchéologique de la région du Sud-ouest et extrême Sud de Madagascar sur la base des collections de l’ICMAA de l’Université d’Antananarivo. TALOHA revue scientifique internationale des civilisations, 1-15 (2005).

Simons, E. L. in Natural Change and Human Impacts in Madagascar (eds S. M. Goodman & B. D. Patterson) 142-168 (Smithsonian Press, 1997).

Anderson, A. et al. New evidence of megafaunal bone damage indicates late colonization of Madagascar. PLOS ONE 13, e0204368, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204368 (2018).

Burney, D. A. in Extinction in Near Time (ed R. D. E. MacPhee) 145-164 (Kluwer/Plenum, 1999).

MacPhee, R. D. E. Environment, extinction, and Holocene vertebrate localities in southern Madagascar. National Geographic Research, 441-455 (1986).

MacPhee, R. D. E., Burney, D. A. & Wells, N. A. Early Holocene chronology and environment of Ampasambazimba, A Malagasy subfossil lemur site. International Journal of Primatology 6, 463–489 (1985).

Lawler, A. Scarred bird bones reveal early settlement on Madagascar. Science 361, 1059–1059, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.361.6407.1059 (2018).

Mitchell, P. Settling Madagascar: When Did People First Colonize the World’s Largest Island? The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 15, 576–595, https://doi.org/10.1080/15564894.2019.1582567 (2020).

Davidson, B., Mhina, J. E. F. & Ogot, B. A. The Growth of African Civilization: East and Central Africa to the Late Nineteenth Century. 329 (Longmans of Kenya Limited, 1967).

Ogot, B. A. Kenya Before 1900 (East African Publishing House, 1976).

Ehret, C. & Posnansky, M. The Archaeological and Linguistic Reconstruction of African History. (University of California Press, 1982).

Wright, H. T. Early Islam, oceanic trade and town development on Nzwani: The Comorian Archipelago in the 11th-15th Centuries. AD. Azania 27, 81–128 (1992).

Wright, H. T., Griffin, W. & Ramilisonina. Early settlements near Belo-Sur-Mer. Unpublished (2015).

Maxon, R. M. East Africa: An Introductory History. (West Virginia University Press, 2009).

Hannaford, M. J. Deep histories of food systems in eastern Africa and current patterns of food insecurity. Nature Food 4, 949–960, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-023-00879-7 (2023).

Marshall, F., Stewart, K. & Barthelme, J. Early domestic stock at Dongodien in northern Kenya. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 19, 120–127, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672708409511332 (1984).

Ndiema, E. K. Mobility and subsistence patterns among mid-Holocene pastoralists at Koobi Fora, northern Kenya: new archaeological sites and evidence from obsidian sourcing and geochemical characterization PhD thesis, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, (2011).

Barthelme, J. Fisher-Hunters and Neolithic Pastoralists in East Turkana, Kenya. (Cambridge Monographs in African Archaeology 13 (B.A.R. International Series 254), 1985).

Young, R. & Thompson, G. in The Exploitation of Plant Resources in Ancient Africa (ed Marijke van der Veen) 63-72 (Springer US, 1999).

Mutundu, K. K. An ethnoarchaeological framework for the identification and distinction of late Holocene archaeological sites in East Africa. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 45, 6–23 (2010).

Prendergast, M. E. Diversity in East African foraging and food producing communities. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 45, 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672700903291674 (2010).

Mitchell, P. & Lane, P. The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology. (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Krzyzaniak, L. & Kobusiewicz, M. Origin and Early Development of Food-Producing Cultures in North-Eastern Africa. (Polish Academy of Sciences and Poznan Archaeological Museum, 1984).

Crowther, A. et al. Coastal subsistence, maritime trade, and the colonization of small offshore islands in eastern African prehistory. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 11, 211–237, https://doi.org/10.1080/15564894.2016.1188334 (2016).

Pawlowicz, M. C. Finding their place in the Swahili world: an archaeological exploration of southern Tanzania PhD thesis, University of Virginia (2011).

Huffman, T. & Vogel, J. The chronology of Great Zimbabwe. The South African Archaeological Bulletin 46, 61, https://doi.org/10.2307/3889086 (1991).

Huffman, T. N. The Early Iron Age and the spread of the Bantu. The South African Archaeological Bulletin 25, 3–21, https://doi.org/10.2307/3888762 (1970).

Robertshaw, P. Archaeology in eastern Africa: recent developments and more dates. The Journal of African History 25, 369–393, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853700028449 (1984).

Radimilahy, C. Mahilaka: An archaeological investigation of an early town in northwestern Madagascar, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, (1998).

Marshall, F. et al. Ancient herders enriched and restructured African grasslands. Nature 561, 387–390, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0456-9 (2018).

Marshall, F. & Hildebrand, E. Cattle before crops: the beginnings of food production in Africa. Journal of World Prehistory 16, 99–143, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1019954903395 (2002).

Marshall, F. Origins of specialized pastoral production in East Africa. American Anthropologist 92, 873–894, https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1990.92.4.02a00020 (1990).

Stahl, A. African Archaeology: A Critical Introduction. (Blackwell, 2005).

Robertshaw, P. & Taylor, D. Climate change and the rise of political complexity in western Uganda. The Journal of African History 41, 1–28, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853799007653 (2000).

Fraedrich, K., Jiang, J., Gerstengarbe, F.-W. & Werner, P. C. Multiscale detection of abrupt climate changes: application to River Nile flood levels. International Journal of Climatology 17, 1301–1315, https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0088(199710)17:12<1301::AIDJOC196>3.0.CO;2-W (1997).

Jiang, J., Mendelssohn, R., Schwing, F. & Fraedrich, K. Coherency detection of multiscale abrupt changes in historic Nile flood levels. Geophysical Research Letters 29, 112-111–112-114, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002GL014826 (2002).

Hassan, F. A. Historical Nile floods and their implications for climatic change. Science 212, 1142–1145, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.212.4499.1142 (1981).

Boivin, N., Crowther, A., Helm, R. & Fuller, D. Q. East Africa and Madagascar in the Indian Ocean world. Journal of World Prehistory 26, 213–281, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10963-013-9067-4 (2013).

Boivin, N., Crowther, A., Prendergast, M. & Fuller, D. Q. Indian Ocean food globalisation and Africa. The African Archaeological Review 31, 547–581 (2014).

Boivin, N., Fuller, D. Q. & Crowther, A. Old World globalization and the Columbian exchange: comparison and contrast. World Archaeology 44, 452–469, https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2012.729404 (2012).

Horton, M. & Middleton, J. The Swahili: The Social Landscape of a Mercantile Society. (Blackwell Publishers, 2000).

Chami, F. A. A review of Swahili archaeology. The African Archaeological Review 15, 199–218 (1998).

Pouwels, R. L. Eastern Africa and the Indian Ocean to 1800: Reviewing relations in historical perspective. The International Journal of African Historical Studies 35, 385–425, https://doi.org/10.2307/3097619 (2002).

Wright, D. K. Environment, chronology and resource exploitation of the Pastoral Neolithic in Tsavo, Kenya PhD thesis, University of Illinois, (2005).

Mehlman, M. J. Later Quaternary Archaeological Sequences in Northern Tanzania PhD thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, (1989).

Odner, K. An archaeological survey of Iramba, Tanzania. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 6, 151–198, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672707109511550 (1971).

Odner, K. A preliminary report on an archaeological survey on the slopes of Kilimanjaro. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 6, 131–149, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672707109511549 (1971).

Odner, K. Usangi Hospital and other archaeological sites in the North Pare Mountains, North-eastern Tanzania. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 6, 89–130, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672707109511548 (1971).

Soper, R. Notes on some caves in Kilifi District. Caves Exploration Group of the East African Society (1975).

Wilson, T. H. & Omar, A. L. Archaeological investigations at Pate. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 32, 31–76, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672709709511587 (1997).

Morales, E. M. Q. Reconstructing Swahili Foodways: the archaeology of fishing and fish consumption in coastal East Africa, AD 500-1500 PhD Unpublished Dissertation thesis, University of Bristol, (2013).

Walshaw, S. C. Swahili urbanization, trade, and food production: botanical perspectives from Pemba Island, Tanzania, A.D. 600-1500 PhD Unpublished Dissertation thesis, Washington University, (2005).

Chami, F. A. & Kwekason, A. Neolithic pottery traditions from the Islands, the Coast and the Interior of East Africa. The African Archaeological Review 20, 65–80 (2003).

Chami, F. A. & Msemwa, P. J. A new look at culture and trade on the Azanian coast. Current Anthropology 38, 673–677 (1997).

Soper, R. Iron Age sites in North-Eastern Tanzania. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 2, 19–36, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672706709511438 (1967).

Soper, R. Archaeological sites in the Chyulu Hills, Kenya. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 11, 83–116, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672707609511232 (1976).

Lyaya, E. C. Change and continuity in metal technology: iron production in the first and second millennium CE in Mbinga, southwestern Tanzania. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 12, 125, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-020-01064-8 (2020).

Chapman, S. A Sirikwa hole on Mount Elgon. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 1, 139–148, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672706609511346 (1966).

Sutton, J. E. G. The archaeology and early peoples of the highlands of Kenya and northern Tanzania. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 1, 37–57, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672706609511340 (1966).

Onjala, I. O. Spatial distribution and settlement system of the stone structures of south-western Kenya. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 38, 99–120 (2003).

Lofgren, L. Stone structures of South Nyanza. Kenya Azania 2, 75–88 (1967).

Odede, F. Gunda-buche: the bank-and-dicth fortified settlement enclosures of western Kenya, Lake Victoria Basin. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 43, 36–49 (2008).

Wandibba, S. in History and Culture in Westem Kenya: The People of Bungoma District through Time (ed S. Wandibba) 11-17 (Gideon S. Were Press, 1985).

Abungu, G. H. O. Communities on the River Tana, Kenya: An archaeological study of relations between the Delta and the River Basin, 700-1890 A.D. PhD dissertation thesis, University of Cambridge (1989).

Davison, S. Early pottery on the Tiwi coast, south of Mombasa. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 28, 127–130, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672709309511651 (1993).

Mosley, P. N. & Davison, S. Ugunja: a new Kansyore (Oltome) site. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 27, 129–134, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672709209511433 (1992).

Phillipson, D. W. Some Iron Age sites in the Lower Tana Valley. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 14, 155–160, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672707909511270 (1979).

Willis, J. The Northern Kayas of the Mijikenda. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 31, 75–98, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672709609511457 (1996).

Abungu, G. H. O. & Mutoro, H. in The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns (eds T. Shaw, P.J.J. Sinclair, B. Andah, & A. Okpoko) 694-704 (Routledge, 1993).

Taylor, R. D. F. The Gumba and ‘Gumba Pits’ of the Fort Hall District, Kenya. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 1, 111–117, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672706609511344 (1966).

Nkirote, M. M. F. Population and ceramic traditions: revisiting the Tana ware of coastal Kenya (7th–14th century AD). Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 47, 245–246, https://doi.org/10.1080/0067270X.2012.674423 (2012).

Kusimba, C. M., Kusimba, S. B. & Dussubieux, L. Beyond the coastalscapes: preindustrial social and political networks in East Africa. African Archaeological Review 30, 399–426, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-013-9133-4 (2013).

Goldstein, S. T. et al. A 9,000 year record of subsistence transitons and population change at Kakapel Rockshelter, western Kenya. PLOS (forthcoming).

Shoemaker, A. Pastoral pasts in the Amboseli landscape: An archaeological exploration of the Amboseli ecosystem from the later Holocene to the colonial Period PhD thesis, Uppsala University, (2018).

Petek, N. & Lane, P. Ethnogenesis and surplus food production: communitas and identity building among nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Ilchamus, Lake Baringo, Kenya. World Archaeology 49, 40–60, https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2016.1259583 (2017).

Gifford-Gonzalez, D. The fauna from Ele Bor: evidence for the persistence of foragers into the later Holocene of arid North Kenya. African Archaeological Review 20, 81–119, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024410814287 (2003).

Gifford-Gonzalez, D. P. & Kimengich, J. in Origin and Early Development of Food-Producing Cultures in North-Eastern Africa (eds L. Krzyzaniak & M. Kobusiewicz) 457-471 (Polish Academy of Sciences and Poznan Archaeological Museum, 1984).

Prendergast, M. et al. Continental island formation and the archaeology of defaunation on Zanzibar, eastern Africa. PLOS ONE 11, e0149565, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0149565 (2016).

Amy, S. J. Inside perspectives on ceramic manufacturing: Visualizing ancient potting practices through Micro-CT scanning Doctor of Philosophy thesis, The University of Western Ontario, (2020).

Barron, A. et al. Sherds as archaeobotanical assemblages: Gua Sireh reconsidered. Antiquity 94, 1325–1336, https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.166 (2020).

Kabiru, A. An exploratory study of Middle Stone Age and Later Stone Age site locations in Kenya’s central Rift Valley using landscape analysis: A GIS approach MSC thesis, Lund University, (2017).

Causey, M. Delineating pastoralist behaviour and long-term environmental change: a GIS landscape approach on the Laikipia Plateau, Kenya, University of Oxford, 2008. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 44, 155–155, https://doi.org/10.1080/00671990902796200 (2009).

Causey, M. & Lane, P. GIS and landscape archaeology: delineating the possible long-term environmental effects of pastoralism on the Laikipia Plateau, Kenya. Nyame Akuma, 24-32 (2005).

Ambrose, S. H., Collett, D., Collett, D. & Marshall, F. Excavations at Deloraine, Rongai, 1978. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 19, 79–104, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672708409511329 (1984).

Shipton, C. et al. Reinvestigation of Kuumbi Cave, Zanzibar, reveals Later Stone Age coastal habitation, early Holocene abandonment and Iron Age reoccupation. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 51, 197–233, https://doi.org/10.1080/0067270X.2016.1173308 (2016).

Sinclair, P., Juma, A. & Chami, F. Excavations at Kuumbi Cave on Zanzibar 2005. (Dar es Salaam University Press, 2006).

Chami, F. A. Zanzibar and the Swahili Coast from c.30,000 Years Ago. (E&D Vision Publishing, 2009).

Culley, C. et al. Collagen fingerprinting traces the introduction of caprines to island eastern Africa. Royal Society Open Science 8, 202341, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.202341 (2021).

Culley, C. et al. Iron Age hunting and herding in coastal eastern Africa: ZooMS identification of domesticates and wild bovids at Panga ya Saidi, Kenya. Journal of Archaeological Science 130, 105368, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2021.105368 (2021).

Nitsche, C., Schreurs, G. & Serneels, V. The enigmatic softstone vessels of northern Madagascar: Petrological investigations of a Medieval Quarry. Journal of Field Archaeology 48, 55–72, https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2022.2092689 (2023).

Serneels, V. et al. Pierre et fer à Madagascar (3) – La carrière de Bobalila. SLSA Jahresbericht – Rapport annuel – 2019 291-352 https://www.unifr.ch/geo/archaeometry/en/assets/public/assets/public/uploads/slsa_jb2019_(p291-352)_madagascar-bobalila_low.pdf (2020).

Serneels, V. et al. Pierre et Fer à Madagascar (1) - Vestiges sidérurgiques de Benavony et de la rivière Matavy. SLSA Jahresbericht – Rapport annuel – Annual report 2017 https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.28729.52326 (2018).

Serneels, V. et al. Pierre et fer à Madagascar (2) – Les scories d’Amboronala et lescarrières de Milanoa. SLSA Jahresbericht – Rapport annuel 2018, 313–366 https://www.unifr.ch/geo/archaeometry/en/assets/public/files/Serneels%20et%20al%202018%20(SLSA).pdf (2019).

M’Mbogori, F. N. (Oxford University Press, 2017).

Godfrey, L. R. et al. A new interpretation of Madagascar’s megafaunal decline: The “Subsistence Shift Hypothesis”. Journal of Human Evolution 130, 126–140, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.03.002 (2019).

Chami, F., Pwiti, G. & Radimilahy, C. People, Contacts and the Environments in the African Past. (University of Dar es Salaam 2001).

Robertshaw, P., Collett, D., Gifford, D. & Mbae, N. B. Shell middens on the shores of Lake Victoria. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 18, 1–43, https://doi.org/10.1080/00672708309511313 (1983).

Chami, F. A. Diffusion in the studies of the African past: reflections from new archaeological findings. The African Archaeological Review 24, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.2307/40645410 (2007).

Chami, F. A. & Chami, R. Narosura pottery from the southern coast of Tanzania: First incontro- vertible coastal Later Stone Age pottery. Nyame akuma, 29-35 (2001).

Chami, F. A. & Silayo, V. V. Neolithic and Early Iron Age settlements of Mount Kilimanjaro’s southern slopes: Re-examining a controversial cultural heritage. Utafiti 18, 135–159, https://doi.org/10.1163/26836408-15020080 (2023).

Kusimba, C. M. & Kusimba, S. B. in African Archaeology: A Critical Introduction (ed Ann Stahl) 392 - 419 (Blackwell, 2005).

Pandora. Pandora data platform. https://pandoradata.earth/organization/afriarch (2024).

United Nations Statistics Division. Standard Country and Area Codes Classifications (M49), <https://web.archive.org/web/20110713041240/http://millenniumindicators.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm> (2011).

Ambrose, S. in From Hunters to Farmers: The Causes and Consequences of Food production in Africa (eds Desmond Clark & Steven A. Brandt) Ch. 21, 212-421 (University of California Press, 1984).

Ambrose, S. H. in The Archaeological and Linguistic Reconstruction of African History (eds Ehret Christopher & Posnansky Merrick) 104-157 (University of California Press, 1982).