Abstract

Boreal forest and Arctic tundra environments collectively hold the largest percentage of global terrestrial seasonal snow cover. Тhe in-situ snow measurement network is sparse and costly in these remote northern regions. Here, we complement existing snow depth monitoring in Arctic tundra and boreal forest by presenting an extensive (64°N–70°N) snow depth dataset and description of ground-based snow depth measurements collected during the NASA SnowEx Alaska intensive field campaign, March 7–16, 2023. We also report the accuracy of snow depth measurements in shallow boreal forest and Arctic tundra snowpack and share considerations in developing the consistent and repeatable snow depth data collection procedures. Snow depth measurements and technical validation described in this paper can serve as a robust product for testing snow remote sensing techniques, and for providing a reference dataset for climatological and hydrological studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Changes in seasonal snow cover play an important role in mass and energy balance at the Earth’s surface by directly impacting water resources1, and surface albedo2 in snow-dominated regions. Boreal forest and Arctic tundra regions comprise the largest percentage (>50%) of seasonal terrestrial snow cover in the world3 and serve an additional role in governing boreal and Arctic hydrology4, animal migration and habitat, permafrost, and biochemical cycling5,6,7. Located in the high latitudes of Eurasia and North America, these northern regions are also especially sensitive to the changes in the snow cover as the Arctic and boreal forest warm at a much faster rate than the rest of the globe8,9,10,11.

Measurements of snow depth and snow water equivalent (SWE) are needed for water resources management, climate change monitoring, avalanche control, design and maintenance of infrastructure. The extent and accuracy of snow measurements is reliant on relevant surface observation networks, which are particularly sparse in boreal forest and Arctic regions12,13. Additional snow data collection often requires specialized equipment, difficult logistics, and demanding operations in harsh weather conditions. This is especially true in remote Arctic locations, where the population is low, and the cost of snow observations is high14. Further, environmental conditions in boreal forest areas have also proven challenging for capturing accurate snow measurements, given the spatial snow heterogeneity15,16,17,18, effect of microtopography and vegetation on snow stratigraphy in permafrost regions15, and vegetation-snow gaps within snow profiles19.

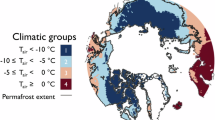

In the USA, the state of Alaska is a well-suited region for developing and testing snow measurement techniques in areas of permafrost, boreal forest, and tundra ecosystems20, because 83% of the state’s land is represented by Interior boreal forest and Arctic tundra snow climates3,21. We complement the existing snow depth monitoring and assessment in boreal forest and Arctic regions by presenting extensive ground-based snow depth measurements collected during the NASA SnowEx Alaska intensive field campaign (March 7–16, 2023)22. SnowEx Alaska was part of NASA’s Terrestrial Hydrology Program series of airborne and ground-based field campaigns designed to improve remotely sensed estimates of snow water equivalent for hydrological applications globally22,23.

Specifically, we (1) provide an overview of the ground-based snow depth measurements taken simultaneously in both boreal forest and Arctic tundra regions between March 7th and 16th, 2023; (2) describe the sampling strategy and the snow depth collection protocols; and (3) discuss snow depth measurement validation and accuracy. We first present the dataset study areas, environmental settings, and experimental design in section “Study areas”. Data collection protocols including spatial sampling patterns, instruments, and techniques used to measure snow depth are described in sections “Spatial patterns of data acquisition”, “Instruments”, and “Measurements techniques”. A summary of published data is given in section “Data records”, followed by a technical analysis of data quality and measurement error (section “Technical validation”).

Applications

There are several intended uses for this snow depth dataset, including complementary data validation, model calibration, and independent analysis. Manual snow depth measurements can be used to validate airborne lidar and Snow Water Equivalent Synthetic Aperture Radar and Radiometer (SWESARR) data generated during NASA SnowEx Alaska campaign24. For example, the coincident airborne lidar snow depths can be directly compared to these point-scale ground-based snow depth measurements to provide an evaluation of lidar performance and accuracy25,26,27. Satellite-derived snow depths (e.g. derived from ICESat-2 or Worldview stereo-imagery) from the same timeframe can also be validated against this dataset28,29,30. For calibration, ground-based snow depth measurements can be used to adjust and correct ground penetrating radar (GPR) derived depths collected at the time of this campaign31,32. Snowpack evolution models can ingest these data for assimilation and calibration33,34. Finally, as an independent analysis, using snow density from snow pits, ground-based snow depth can be converted into SWE using a statistical model or a physically based model and compared directly to the SWESARR-derived SWE, similar to the studies conducted in other regions35,36,37. Thus, the snow depth measurements presented here can be used in several ways for improved representation of spatially distributed snow depth and SWE in Arctic tundra and boreal forest.

Methods of data collection

Study areas

Arctic tundra and Interior boreal forest environments have climate and weather conditions (precipitation, wind, air temperature, etc.) as well as terrain (aspect, elevation, etc.), land cover type (vegetation and organic soil), and continuous or discontinuous permafrost, that affect snow measurement techniques, remote sensing, and modelling in a way that is distinct from other snow climates.

To account for wide range of conditions and associated snow variability, snow depth measurements were collected across five study areas (Fig. 1): 1) Bonanza Creek Experimental Forest (BCEF), 2) Caribou Poker Creek Research Watershed (CPCRW), 3) Farmers Loop and Creamer’s Field (FLCF), 4) Upper Kuparuk and Toolik (UKT), and 5) Arctic Coastal Plain (ACP)13,16. These study areas were not chosen randomly. Instead, the decision-making process was based on safety considerations, airborne and ground-based data collection activities, area access and required permits, corner reflector deployments, historical snow datasets, and sampling strategy. Stratified random sampling was employed to locate individual study plots shown as black dots in Fig. 1b–f. NASA SnowEx Alaska experimental plan was developed to provide a full description of experimental design22,23. Here, we present description of methods relevant to the ground-based snow depth data collection.

Overview map with the state of Alaska and five study areas for March 2023 SnowEx Alaska campaign (a). Locations of study areas, snow plots, weather stations, lidar, and SWESARR swaths are shown for each study area (b–f). Background images are courtesy of Maxar Technologies Inc., Alaska Geospatial Office, USGS. Detailed field maps (A1–A5) are provided in Appendix A.

Arctic tundra

Arctic tundra snow depth measurements were collected in the ACP and UKT study areas (Fig. 1). Both study areas were sub-divided into four classes based on snow deposition patterns, land cover characteristics, terrain, and prevailing wind direction. The physically based, spatially-distributed SnowModel34,38 was applied to produce four snow classes: neutral or average (windward), above average (leeward), snow drifts, and ice cover (lakes/rivers). Model simulations were performed on a 30 m grid using USGS National Elevation Dataset, North American Land Change Monitoring System Land Cover Class Definition Level 2 classification, and MERRA-2 reanalysis forcing. Individual ground-based measurement locations (snow plots) were then selected within four classes using stratified random sampling.

Stratified random sampling approach was chosen because an Arctic snowpack is on average shallow (snow depth is 30–50 cm), but wind redistribution of snow creates scour zones and deep drifts. These seasonal snow cover patterns evolve for most of the year: snow onset occurs in late September or October, and snow persists on the ground through April without any intermittent snowmelt runoff34. Terrain, microtopography, and vegetation affect snow deposition patterns. Between the ACP and UKT study areas, the elevation ranges from 25 m to 1360 m above sea level. The ACP study area has low-gradient terrain with polygonal tundra, wetlands, and lakes (Figure A1), while the UKT study area includes rolling hills and mountains of the northern Brooks Range (Figure A2). Both Arctic study areas are selected for their location within the tundra snow class above the latitudinal treeline (no forest). Low-growing vegetation (tussocks, mosses, lichens, graminoids, shrubs) with a developed organic layer on top of mineral soil is typical for Arctic tundra sites39,40,41.

Tundra vegetation at the majority of the sites visited during the March 2023 campaign was completely covered by snow. There were some scoured zones (shallow snowpack or no snow at all), where vegetation was exposed to the atmosphere, e.g. area near plot N667 in the UK_North swath (Figure A2). At other sites, shrubs protruded above the snow surface, e.g. area near plot N742 in the UK_South swath (Figure A2).

Boreal forest

Snow depth measurements were collected in three boreal forest study areas (BCEF, CPCRW, and FLCF) to represent a wide range of boreal forest vegetation. These study areas are located within discontinuous permafrost and on rolling hills (120–800 m above sea level) around Fairbanks (Fig. 1a), covered by evergreen, deciduous, and mixed forest with shrubs and brush (Figure A3–A5). Unforested areas consist of wetlands at the BCEF, meadows and fields at the FLCF, and some alpine tundra at the ridgetop of the CPCRW. The climate is characterized by long winters, low humidity, and low precipitation (250–400 mm/yr) (1981–2010)21.

Individual snow measurement sites in boreal forest were selected within snow-vegetation classes using stratified random sampling. Vegetation was sub-divided into five classes (deciduous forest, evergreen forest, wetlands, shrub scrub, and cultivated crop) using the National Land Cover Dataset and prior research15. Three snow depth classes (below average, average, and above average snow depth) were retrieved from the airborne lidar-derived snow depths products. Combination of five vegetation classes and three snow depth classes produced 15 snow-vegetation classes. Overall, the inclusion of 15 classes supported one of the SnowEx Alaska science questions: “How well do snow depth retrieval methods (e.g., lidar and SfM) work in the variable permafrost, water, and vegetation characteristics ubiquitous at high latitudes?”

The presence of an organic substrate layer under the snowpack is a distinct feature impacting most snow depth measurements within all five study areas (see section “Measurement error, uncertainty, and limitations” for more details). The organic layer consists of plant debris, moss, lichens, and vascular plant roots that accumulate and decompose on top of mineral soil, forming a soft substrate for overlying snowpack that affects snow depth measurement accuracy.

Spatial patterns of data acquisition

The data collection protocol was developed to bridge the difference in spatial scales between airborne and ground-based snow measurements. We collected manual snow depth measurements in different spatial patterns (Table 1) over a variable area within and around each study plot (Fig. 2) to address science and measurement questions formulated in SnowEx experiment plan20,22,23.

Ground-based measurements with different instruments, spatial patterns, and techniques used to measure snow depth at each plot: (a) magnaprobe and snow pit measurements in an Arctic tundra setting (UKT, March 12, 2023). Note fresh snow on top of the snowpack; (b) dense, heavy wind slab from the middle of the snowpack in the hands of the SnowEx participant; and (c) detailed snow depth measurements around the snow pit co-located with ground penetrating radar and magnaprobe measurements (FLCF, March 15, 2023). Field participants in the photographs provided consent to having their likenesses published in the manuscript.

The study plot was defined as a 5 m by 5 m square box with detailed snow pit, snow depth, and vegetation measurements (Fig. 2). Each study plot included a single pit-depth and a combination of square-depths, L-depths, or spiral-depths (Figs. 2, 3). During the campaign, the choice of snow depth data patterns at specific plot location was also influenced by instrument availability, weather conditions, time, and safety considerations.

Examples of snow depth measurements taken in different spatial patterns: (a) shows pit-depth, square-depths with L-depths from one of the plots in FLCF; (b) captures spiral-depths at one of the plots in UKT; and (c) includes transect and spiral-depths at UKT. Note the difference in scale across each panel, representing different spatial extents of sampling patterns. Colours represent snow depth values.

Instruments used to measure snow depth and geographical position

The snow depth measurements were taken with manual and self-recording instruments including a plastic and fiberglass folding 2 m ruler, aluminium depth probe with interlocking 1 m sections, aluminium folding 3.2 m avalanche probe, and self-recording magnetic steel snow depth probe (magnaprobe).

Rulers, depth probes, and avalanche probes were used to collect manual depth measurements (Table 2). These instruments were operated by different users and measurements were written in the field books. Some of the manual depth probe measurements (1722 points) were co-located with magnaprobe measurements for calculating accuracy and uncertainty of snow depth measurements between the instruments. The accuracy of measurements is discussed in section “Measurement error, uncertainty, and limitations”.

The geographical position of each manual snow depth data point was measured with a compass and tape from the southeast (SE) corner of the study plot (Table 2, PR and P data code abbreviations). Around some plots, the geographical positions of L-depth or square-depth were recorded with a mapping-grade GPS (Juniper Systems Mesa2 tablet connected via Bluetooth to a Geode GNSS receiver) and depth measurements were made with a manual depth probe (Table 2, M2 data code abbreviation).

We used magnaprobes to measure both snow depth and geographical position42. The main components of a magnaprobe are a 1.5 m rod (MTS Temposonics G-Series probe), a basket with a magnet that slides on the rod, Garmin GPS16X-HVS for measuring position, Campbell Scientific CR800 series logger for recording data, and a battery for power supply. The magnaprobe can measure the range of snow depths from 0 to 1.2 m. An avalanche probe was used when snow depth exceeded 1.2 m; and corresponding manual depth measurement was recorded in the field book.

Measurement techniques and data processing

Manual snow depth measurements: ruler, manual depth probe, and avalanche probe

Traditional pit-depth measurements were taken with a ruler in the center of the 1 m snow pit wall or closest to the dual-column density profiles (Fig. 3). The pit ruler was placed on the ground surface and a height of snow was recorded in the snow pit field book. Data processing included extracting the recorded pit-depth from the field book and calculating latitude and longitude of snow pit location relative to the position of the previously defined study plot south-east corner.

The square-depths and L-depths were measured two ways: (1) by manually inserting the depth probe into the snow and reading the snow surface height; and (2) by carefully digging a hole in the snow and recording the top and the bottom depth measurement to account for errors in snow depth measurements associated with low growing vegetation, air voids, ice crusts, penetration of an instrument into the underlying organic layer, and other factors affecting the accuracy of the measurement process (Fig. 3). We grouped these more accurate measurements into a separate “snow depth profile” dataset and used accurate snow depths to calculate measurement error.

Data processing of square-depths and L-depths included extracting the recorded snow depth from the field book and calculating or extracting latitude and longitude depending on the approach used to measure geographical position (Table 2). At all study plots, the navigation-grade GPS units were used to record the position of the SE corner (Fig. 2a). Compass and tape were utilized to lay out direction and position of the square-depth and L-depth measurements from study plot SE corner, as well as to locate the snow pit wall in the center of the study plot (Fig. 2a). Latitude and longitude of each point were calculated using GPS coordinates of the SE corner and distance of 1 m spacing from SE corner in a specified direction.

When a Juniper Systems Mesa2/Geode was used to determine position of the snow depth measurement (Table 2), we attached the Geode GNSS receiver to the metal depth probe with a custom mount, and we entered the observed snow depth into the Mesa2, using the Uinta software. The recorded snow depth and its x, y, z positions were then exported to a CSV file. The locations were not post-processed, but we did use real time DGPS corrections.

Self-recording snow depth measurements: magnaprobe

The magnaprobe snow depths were measured by inserting a magnetic pole into the snow and by pressing a button on the pole to record instantaneous measurements of date, time, latitude, longitude, elevation, snow depth, battery voltage, and other ancillary information. The magnetic pole calibration data were collected at each study plot by taking a zero reading with a basket placed at the tip of the rod and then sliding the basket to the highest point to verify the calibration factor. At the end of each field day, magnaprobe measurements were downloaded from the data logger and reviewed for completeness.

Post-processing of magnaprobe measurements was done with raw instrument outputs (data logger files) and observer field notes. Typical workflow was to 1) locate and read observer field notes, 2) remove calibration data from raw files, 3) identify and remove erroneous data (false measurements or misfires), 4) correct deeper snow depth (deeper than 1.2 m) based on simultaneous manual snow depth measurements recorded in field books, 5) calculate latitude and longitude from GPS measurements, and 6) plot snow depth points in a GIS or similar software to ensure measurements were co-located with snow pit locations.

Data Records

The SnowEx March 2023 snow depth data43 can be accessed at the National Snow and Ice Data Center under https://doi.org/10.5067/6QD3UJVABY6D and Zenodo open research repository44. The total number of snow depth measurements is 26,752. All measurements and supporting information are combined in a single CSV file (Table 3) and described in the dataset user guide43.

Technical Validation

The purpose of this section is to provide technical analyses supporting the quality of the snow depth measurements including: (1) basic statistical analysis of snow depths, (2) analysis of measurements made during March 2023 in the context of the 2023 water year’s precipitation climatology and snow accumulation, and (3) evaluation of error and uncertainty in snow depth measurements.

Statistical analysis of snow depths

We conducted basic statistical analyses comparing the snow depth means, medians, standard deviations, and distributions between study areas and between snow classes. Non-parametric two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test was used to assess similarity between cumulative distribution functions and Wilcoxon rank sum was applied to determine if there is a significant difference between the medians. Overall, tundra snow was more shallow than boreal forest snow; tundra locations yielded 55% of the mean snow depth found at the boreal forest locations. The mean snow depth (\(\overline{{HS}}\)) and standard deviation (SD) were \(\overline{{HS}}\,=\,\) 42 cm, SD = 18 cm for Arctic tundra and \(\overline{{HS}}\,=\,\) 76 cm, SD = 16 cm for boreal forest (Fig. 4). The KS and Wilcoxon tests indicated that there are statistically significant differences in snow depth distributions (KS) and median values (Wilcoxon) between tundra and boreal forest snow depths at 5% significance level.

Summary of tundra and boreal forest snow depth measurements collected during March 7–16, 2023. (a) Snow depth variability is presented as a box and whisker plot with minimum and maximum snow depths shown by whiskers, and median snow depth printed inside each box. The upper and lower boundaries of the box represent the lower and upper quartiles (a). Histogram plots snow depth distribution, mean, standard deviation (SD), coefficient of variation (CV) and skew (CS) in tundra (b) and boreal forest (c).

Overall, a larger range in snow depth (0–190 cm) was measured in the Arctic tundra locations due to wind exposure, while boreal forest snow depths varied from 0–139 cm (Fig. 4). The driving factor for large variability in tundra snow depth is winter-long snow redistribution by wind. Wind causes snow erosion in scoured areas, resulting in shallow snow depths (0–30 cm), and it promotes snow deposition in leeward areas and topographic depressions, resulting in snow drifts (e.g. 190 cm) (Fig. 4).

Interactions between forest canopy, solid precipitation, and weather were driving factors for snow depth variability observed across boreal forest study areas. Snow redistribution by wind played an insignificant role in forested sites. On average, the coefficient of variation (CV) in boreal forest snow depth (0.21) is half the CV in Arctic tundra snow depths (0.42), mainly due to differences in mean snow depths (76 cm and 42 cm) between the two snow classes.

Among study areas (Table 4), CPCRW had the deepest average snow depth (\(\overline{{HS}}\,=\,\) 86 cm), followed by BCEF (\(\overline{{HS}}\,=\,\) 79 cm) and FLCF (\(\overline{{HS}}\,=\,\) 71). The most northern study area (ACP) had the least amount of snow (\(\overline{{HS}}\,=\,\) 34), followed by UKT, the second most northern study area (\(\overline{{HS}}\,=\,\) 45). The differences in snow depths (HS and CV) between snow classes are greater than the differences in snow depth between study areas.

Comparison of March 2023 snow depths to climatological precipitation and remote weather station snow depth records

Arctic tundra

Across the UKT study area, March 2023 measurements occurred at near maximum snow accumulation as shown by snow depth and cumulative daily precipitation recorded by nearby weather and snow monitoring stations (Fig. 5). Winter precipitation accumulation was above average during the 2022–2023 winter compared to the 1991–2020 climatological average precipitation (Fig. 5). The automated shielded precipitation gauge accumulated 86 mm of precipitation between October 1, 2022, and March 18, 2023, which corresponded to 117% of 1991–2020 average cumulative precipitation (74 mm). There was fresh snow accumulation with 14 cm, 2 cm, and 4 cm of freshly fallen snow depth on March 8, 11, and 13, 2023, respectively. The 24-hr snowfall measurements were taken with an interval board at Toolik Field Station. Interval board measurements summed to 20 mm of SWE during March 7–16, 2023, whereas the precipitation gauge at Imnavait Creek recorded 7 mm of precipitation during the same period. This discrepancy is another reminder of wind-induced precipitation gauge under-catch (13 mm in this case) and other challenges associated with solid precipitation measurements by automated gauges in the Arctic45.

Cumulative precipitation and snow depth accumulation during the SnowEx Alaska March 2023 Intensive Observing Period (IOP) and historical averages at the UKT study area. Cumulative daily precipitation in 2022–2023 (blue solid line) is plotted alongside average cumulative daily precipitation from 1991–2020 (green dashed line, Imnaviat [sic] SNOTEL). The March 2023 IOP magnaprobe snow depths collected at the UKT study area are plotted as a box and whisker plot to highlight the large range of snow depth variability (0–190 cm). The boxplot also shows that most of the snow depth falls within the 34–54 cm range (2nd and 3rd quartiles) with 45 cm of median snow depth. Seasonal snow depths recorded by two automated weather stations (US-ICs and US-Ich fall within the 2nd and 3rd quartile, while snow depth at automated weather station UKmet represents snow drift) (dashed orange, purple, and black lines).

From the continuous automated snow depth records (Fig. 5), we can see that March 2023 measurements are close to the maximum snow depths during the 2022–2023 snow accumulation season. Snow depths from two weather stations (AmeriFlux site IDs are US-ICs and US-Ich, data are available at the AmeriFlux website https://ameriflux.lbl.gov/sites/site-search/?availability) are within the March 2023 snow depth interquartile range, and close to the median snow depths for the UKT study area. Snow depth measured at the UKmet weather station is above average, as it captures snow deposition in a snow drifted area (see Fig. 5 for snow depth data and Fig. 1 for the geographic location of the weather stations). The ACP study area does not have enough weather station winter records to present an analysis similar to that of the UKT study area.

Boreal forest

In Fairbanks, winter precipitation in 2022–2023 was above normal compared to the 1991–2020 climatological average precipitation (Fig. 6). During March 7–16, 2023, the weather station at Fairbanks International Airport reported a cumulative winter precipitation 130% of normal. The March 2023 measurements in the boreal forest study areas occurred close to the maximum snow accumulation; however, late March and April brought an additional 15 mm of solid precipitation to Fairbanks (Fig. 6).

Cumulative precipitation and snow depth accumulation during the SnowEx Alaska March 2023 Intensive Observing Period (IOP) and historical averages at the boreal forest study areas. Cumulative hourly precipitation in 2022–2023 (blue solid line) is plotted with the cumulative daily precipitation averaged during 1991–2020 (green dashed line, Fairbanks International Airport). The March 2023 IOP magnaprobe snow depths collected at the boreal forest study areas are plotted as box and whisker plot. Seasonal snow depth evolution is recorded by three automated weather stations (LTER2 at BCEF, SCFA2 at FLCF, and US-Rpf near CPCRW (dashed orange, purple, and black lines)). LTER2 is located in the forest opening, SCFA2 is located on the field, US-Rpf is located in black spruce forest.

From the automated snow depth data, we can see that March 2023 measurements occur close to the maximum snow depths recorded during the 2022–2023 snow evolution season (Fig. 6 for snow depth data and Fig. 1 for geographic location of the weather stations). Automated snow depth time series fall within the 1st quartile of snow depths measured in all boreal forest study areas (Fig. 6). The three long-term automated snow depth records were not representative of the median snow depth collected during the campaign’s spatial surveys, illustrating the importance of coincident and spatially distributed manual snow measurements during remote sensing campaigns.

Measurement error, uncertainty, and limitations

Snow depth error is associated with both the vertical accuracy of the snow depth measurement and the accuracy of the horizontal positioning of the measurement points. The vertical accuracy of snow depth measurements depends on the instrument, technique, observer, nature of the snowpack, vegetation, and snowpack substrate. The nature of the snowpack (primarily hardness and depth) dictated how easily or how challenging it was to penetrate the snowpack and the substrate with the snow depth probe (Fig. 7).

Schematic diagram of measurement errors associated with overestimation of snow depth (a) and underestimation of snow depth (b) in a typical tundra snowpack (modified from Stuefer et al., 2020). Both issues exist in the boreal forest in some cases: (a) often and (b) sometimes. Another source of measurement error in forested areas is associated with air voids due to an elevated snowpack, suspended by vegetation (c).

The boreal forest plots had typically low density snow, and much of the snowpack was composed of faceted grains, many of which were depth hoar17. A basal ice layer was observed in some locations, both on the forest floor and in the depressions between tussocks (similar to Fig. 7b, except the ice layer was positioned at the snow-ground interface)17,45,46,47. In tundra study areas (Fig. 7a), the snowpack consisted of dense wind-packed layers overlying or interspersed with weak faceted layers. An ice layer was also observed in many tundra snow pits at UKT (Figs. 2b, 7b), caused by a December 2022 rain-on-snow event. A soft organic layer was common in study plots in both boreal forest and tundra snow environments with coarse grain, low density depth hoar snow layer above and around vegetation17,46,47,48.

Measurement error for the magnaprobe was quantified from the co-located measurements of snow depth with magnaprobe (HSMP) and true depth (HS) calculated from excavated snow depth profiles. HS measurements were performed after excavation, which prevented the errors shown in Fig. 7. Comparison of HSMP and HS showed that error is variable with larger scatter across the boreal forest study plots (R2 = 0.46) than the Arctic tundra study plots (R2 = 0.82). The bias in magnaprobe depths was 10 cm for boreal forest snow and 1 cm for Arctic tundra snow (Fig. 8). The root mean squared error (RMSE) varied from 6.3 cm in Arctic tundra to 12.1 cm in boreal forest. The fact that the RMSE is twice the value in the boreal forest versus the tundra environment may be due to the prevalence of air gaps within the snowpack elevated by vegetation or to thicker penetrable basal vegetation and organic layer in the boreal regions. Horizontal positioning is also less accurate in forested areas and is a possible contributor to larger RMSE.

Comparison of snow depths measured with magnaprobe and manual snow depths retrieved from snow depth profiles to assess the measurement error in boreal forest (a) and Arctic tundra (b) during March 2023 IOP. The 1:1 line is plotted as a gray solid line, and the regression is plotted as a red dashed line.

Magnaprobe measurements that plot below the 1:1 line in Fig. 8 represent underestimated snow depth. Underestimation error was likely associated with the instrument basket sinking into the top layer of freshly fallen snow (Fig. 2a) or the presence of an impenetrable ice crust which prevented the instrument from reaching the snow-ground interface. Magnaprobe measurements that plot above the 1:1 line in Fig. 8 represent overestimated snow depth. Overestimation error was likely due to penetration of the probe into the vegetation and organic layer (Fig. 7a). In forested areas, overestimation error was reported when the snowpack bottom was suspended by shrubs, deadfall, or had air voids (Figs. 7c, 9).

Examples of depth measurements in the boreal forest (BCEF and CPCRW). These areas were excavated after measuring initial snow depth (without excavation) to obtain true snow depth. Two sources of errors in depth measurements are demonstrated: magnaprobe (MP) basket depression (a) and air void due to elevated snowpack over vegetation (b,c).

Photographs of field snow measurements and likely sources of error are shown in Fig. 9, including an air gap below snowpack (Fig. 9a,c) and the depression of the magnaprobe basket into the weak surface snow. The boreal forest vegetation (low-lying bushes, tree branches, and trees) that result in the elevated snowpack can be seen in Fig. 9b. The two vertical marks in the pit walls are from the magnaprobe shaft, which are spaced 1 m apart (Fig. 9a). The manual probe shaft on the left is pointing at a magnaprobe basket depression of approximately 3 cm.

The measurement errors associated with horizontal positioning also varied between instruments and environments. For navigation-grade GPS units and magnaprobe GPS, the horizontal positioning accuracy reported in instrument specifications was within ±3.0 m and ±2.5 m, respectively. Horizontal accuracy of navigation grade GPS may degrade to ±15.0 m depending on number visible satellites and obstructed sky view in forested areas. Juniper Systems Geode GNSS (Mesa2) position errors were sub-meter, and with good sky view and the northern latitude, we often had estimated horizontal position uncertainties of less than 0.3 m.

The conclusion that came from measurements uncertainty analysis is that topography, vegetation, substrate, and internal snowpack properties complicate snowpack property measurements and retrievals in complex ways, difficult or impossible to quantify without direct field measurements. This conclusion is true for all platforms, airborne or spaceborne, and ground measurements, and for all snowpack properties including snow depth and snow water equivalent.

Usage Notes

While spatially expansive, this dataset is not intended to represent the entirety of the Alaskan boreal and Arctic landscapes, nor represent spatial heterogeneity of snow depth throughout all accumulation and ablation seasons. Thus, complementary datasets are needed to expand the temporal domains.

There are several airborne and ground-based datasets collected during SnowEx Alaska that provide further information on snowpack properties49, vegetation, and soil characteristics (Table 5). NASA SnowEx datasets can be found at NSIDC website (https://nsidc.org/data/snowex). NASA SnowEx Alaska experiment plan provides comprehensive in-depth information on scope of the project and datasets22.

Code availability

There is no custom code generated to process data described in this manuscript, most of the work to digitize field notes and perform QA/QC of the manual and automated snow depth measurements was done in ArcGIS, NotePad++, MS Excel, and Matlab using embedded functions.

Change history

26 June 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05430-w

References

Barnett, T. P., Adam, J. C. & Lettenmaier, D. P. Potential impacts of a warming climate on water availability in snow-dominated regions. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04141 (2005).

Groisman, P. Y., Karl, T. R., Knight, R. W. & Stenchikov, G. L. Changes of snow cover, temperature, and radiative heat balance over the Northern Hemisphere. J Clim 7 (1994).

Sturm, M. & Liston, G. E. Revisiting the global seasonal snow classification: an updated dataset for Earth system applications. J Hydrometeorol https://doi.org/10.1175/jhm-d-21-0070.1 (2021).

Bring, A. et al. Arctic terrestrial hydrology: A synthesis of processes, regional effects and research challenges. J Geophys Res Biogeosci 121, 621–649 (2016).

Jan, A. & Painter, S. L. Permafrost thermal conditions are sensitive to shifts in snow timing. Environmental Research Letters 15 (2020).

Natali, S. M. et al. Large loss of CO2 in winter observed across the northern permafrost region. Nat Clim Chang 9, 852–857 (2019).

Rixen, C. et al. Winters are changing: Snow effects on Arctic and alpine tundra ecosystems. Arct Sci 8, 572–608 (2022).

Rantanen, M. et al. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Commun Earth Environ 3 (2022).

Derksen, C. & Brown, R. Spring snow cover extent reductions in the 2008–2012 period exceeding climate model projections. Geophys Res Lett 39 (2012).

Price, D. T. et al. Anticipating the consequences of climate change for Canada’s boreal forest ecosystems1. Environmental Reviews 21, 322–365, https://doi.org/10.1139/er-2013-0042 (2013).

Scheffer, M., Hirota, M., Holmgren, M., Van Nes, E. H. & Chapin, F. S. Thresholds for boreal biome transitions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 21384–21389 (2012).

Stuefer, S. L., Kane, D. L. & Dean, K. M. Snow water equivalent measurements in remote Arctic Alaska watersheds. Water Resour Res 56 (2020).

Ye, H. et al. Precipitation characteristics and changes. in Arctic Hydrology, Permafrost and Ecosystems. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50930-9_2 (2021).

AMAP - Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme. Arctic Climate Change Update 2019: An Update to Key Findings of Snow, Water, Ice, and Permafrost in the Arctic (SWIPA) 2017. Assessement report (2019).

Komarov, A. & Sturm, M. Local variability of a taiga snow cover due to vegetation and microtopography. Arct Antarct Alp Res 55 (2023).

Parajuli, A. et al. Exploring the spatiotemporal variability of the snow water equivalent in a small boreal forest catchment through observation and modelling. Hydrol Process 34, 2628–2644 (2020).

Sturm, M. Snow Distribution and Heat Flow in the Taiga. Arctic and Alpine Research 24 (1992).

Sturm, M. & Benson, C. Scales of spatial heterogeneity for perennial and seasonal snow layers. Ann Glaciol 38, 253–260 (2004).

Berezovskaya, S. & Kane, D. L. Measuring snow water equivalent for hydrological applications: part 1, accuracy of observations. 16th International Northern Research Basins Symposium and Workshop Petrozavodsk, Russia, 27 Aug. – 2 Sept. 2007 (2007).

Hiemstra, C. & Durand, M. SnowEx Alaska Activity Implementation Plan v.14. (2020).

Shulski, M. & Wendler, G. Climate of Alaska. (University of Alaska Press, 2007).

Vuyovich, C. et al. NASA SnowEx 2023 Experiment Plan. (2023).

Durand, M. et al. NASA SnowEx Science Plan: Assessing Approaches for Measuring Water in Earth’s Seasonal Snow. (2019).

Larsen, C. SnowEx23 airborne lidar-derived snow depth and canopy height, version 1. NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center https://doi.org/10.5067/BV4D8RRU1H7U (2024).

Parr, C., Sturm, M. & Larsen, C. Snowdrift landscape patterns: an Arctic investigation. Water Resour Res 56 (2020).

Bonnell, R. et al. Evaluating L-band InSAR snow water equivalent retrievals with repeat ground-penetrating radar and terrestrial lidar surveys in northern Colorado. Cryosphere 18, 3765–3785 (2024).

Hoppinen, Z. et al. Snow water equivalent retrieval over Idaho – Part 2: Using L-band UAVSAR repeat-pass interferometry. Cryosphere 18, 575–592 (2024).

Besso, H., Shean, D. & Lundquist, J. D. Mountain snow depth retrievals from customized processing of ICESat-2 satellite laser altimetry. Remote Sens Environ 300 (2024).

Fair, Z. et al. Characterizing ICESat-2 snow depths over the boreal forests and tundra of Alaska in support of the SnowEx 2023 campaign. https://doi.org/10.22541/essoar.172927223.38169790/v1 (2024).

Hoppinen, Z. et al. Evaluating snow depth retrievals from Sentinel-1 volume scattering over NASA SnowEx sites. Cryosphere 18, 5407–5430 (2024).

McGrath, D. et al. Spatially extensive ground-penetrating radar snow depth observations during NASA’s 2017 SnowEx campaign: comparison with in situ, airborne, and satellite observations. Water Resour Res 55, 10026–10036 (2019).

Marshall, H. et al. NASA SnowEx 2020 Experiment Plan. (2019).

Liston, G. E. & Hiemstra, C. A. A simple data assimilation system for complex snow distributions (SnowAssim). J Hydrometeorol https://doi.org/10.1175/2008JHM871.1 (2008).

Stuefer, S., Kane, D. L. & Liston, G. E. In situ snow water equivalent observations in the US arctic. Hydrology Research 44, 21–34 (2013).

Lemmetyinen, J. et al. Airborne SnowSAR data at X and Ku bands over boreal forest, alpine and tundra snow cover. Earth Syst Sci Data 14 (2022).

Montpetit, B. et al. Retrieval of snow and soil properties for forward radiative transfer modeling of airborne Ku-band SAR to estimate snow water equivalent: the Trail Valley Creek 2018/19 snow experiment. Cryosphere 18, 3857–3874 (2024).

Rincon, R. et al. Performance of Swesarr’s Multi-Frequency Dual-Polarimetry Synthetic Aperture Radar during Nasa’S Snowex Airborne Campaign. in International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS) 6150–6153, https://doi.org/10.1109/IGARSS39084.2020.9324391 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2020).

Liston, G. E. & Elder, K. A distributed snow-evolution modeling system (SnowModel). J Hydrometeorol https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM548.1 (2006).

Kade, A., Walker, D. A. & Raynolds, M. K. Plant communities and soils in cryoturbated tundra along a bioclimate gradient in the Low Arctic, Alaska. Phytocoenologia 35, 761–820 (2005).

Sturm, M. et al. Snow-Shrub Interactions in Arctic Tundra: A Hypothesis with Climatic Implications. J Clim 14, 336–344 (2001).

Kane, D. L. & Carlson, R. F. Hydrology of the Central Arctic River Basins of Alaska. Technical report IWR no. 41, https://scholarworks.alaska.edu/handle/11122/1792 (1973).

Sturm, M. & Holmgren, J. An automatic snow depth probe for field validation campaigns. Water Resour Res 54, 9695–9701 (2018).

Stuefer, S. et al. SnowEx23 Mar23 IOP community snow depth measurements. NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center https://doi.org/10.5067/6QD3UJVABY6D (2024).

Stuefer, S. et al. SnowEx23 Mar23 IOP Community Snow Depth Measurements, Version 1. https://zenodo.org/records/15284684https://doi.org/10.5067/6QD3UJVABY6D.

Janowicz, J. R., Stuefer, S. L., Sand, K. & Leppanen, L. Measuring winter precipitation and snow on the ground in northern polar regions. Hydrology Research 48 (2017).

Derksen, C. et al. Physical properties of arctic versus subarctic snow: Implications for high latitude passive microwave snow water equivalent retrievals. J Geophys Res 119 (2014).

Domine, F. et al. Soil moisture, wind speed and depth hoar formation in the Arctic snowpack. Journal of Glaciology 64 (2018).

Benson, C. & Sturm, M. Structure and wind transport of seasonal snow on the Arctic Slope of Alaska. Ann Glaciol 18, 261–267 (1993).

Mason, M. et al. SnowEx23 Mar23 Snow Pit Measurements. NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center https://doi.org/10.5067/SJZ90KNPKCYR (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge access to, and use of, unceded land in the traditional territories of Indigenous peoples of the Inupiaq and Tanana nations. We thank SnowEx Alaska March 2023 participants – a team of 46 scientists, practitioners, and engineers from 18 organizations in the U.S., Canada, Finland, and the Netherlands – for their dedicated field work and careful data collection. UAF’s Toolik Field Station provided accommodation and logistical support for participants working in the Arctic. Dr. Glen Liston provided valuable input on snow classifications in the Arctic tundra. Emily Youcha prepared field maps for all participants. The Arctic Climate Research Center (UAF) provided solid precipitation data at Fairbanks. We thank the Editor and three anonymous Reviewers for providing peer-review of this manuscript. Funding was provided by NASA grants 80NSSC21K1913, 80NSSC22K1114, 80NSSC23K1419, and 80NSSC21M0321.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors participated in the field data collection. M. Mason, L. May, and S. Stuefer processed the field snow depth data. S. Stuefer wrote the original draft; K. Hale, K. Elder, H.P. Marshall contributed text for sections of the manuscript; C. Vuyovich, D. Vas, K. Hale, K. Elder, L. May, M. Mason, H.P. Marshall reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stuefer, S.L., Hale, K., May, L.D. et al. Snow depth measurements from Arctic tundra and boreal forest collected during NASA SnowEx Alaska campaign. Sci Data 12, 919 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05170-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05170-x