Abstract

Changes in the global ocean salinity reflect the evolution of the global hydrological cycle. These secular changes are assessed using seawater salinity profiles obtained during the past ~80 years. Here, we introduce a new global ocean salinity profiles database named CODC-S (the Chinese Academy of Science (CAS) Oceanography Data Center – Salinity component), which encompasses over 11 million in-situ salinity profiles from 1940 to 2023 obtained by means of several instrument types. These salinity profiles are quality-controlled (QC-ed) using a new automated salinity quality control system named CODC-QC-S (the CODC Quality Control system – Salinity component), consisting of 11 distinct quality checks. By applying time-varying, flow-dependent, and topographical-dependent 0.5% and 99.5% quantile thresholds, the CODC-QC-S defines local climatology salinity ranges without the assumption of Gaussian distribution. The CODC-S database, together with the newly proposed QC algorithm, has undergone extensive evaluations, including comparisons with the benchmark data and climatology, as well as analyses of global and basin-scale long-term salinity changes before and after QC. These validations demonstrate that the quality of salinity data in the CODC-S is time-, depth-, region- and instrument type-dependent. The eight-decade quality-homogeneous salinity profiles from the CODC-S database can support diverse oceanographic and climatic research such as monitoring water cycle changes and freshwater/overturning transports.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Ocean salinity, an indicator of the global hydrological cycle, is one of the most important physical parameters of sea water1,2,3. Ocean salinity changes can affect marine physical and biogeochemical conditions, including geostrophic currents4, density stratification5, mixed layer structure, and vertical movement of nutrients and marine organisms6,7. Salinity is also one of the climatic impact-drivers (CIDs) linking the information from ocean physical changes to the climate change impact8,9,10. For example, suitable salinity determines physiological levels of marine species, but excessive/limited salinity (freshening/salinization) may cause a redistribution of marine life11. Our knowledge of ocean salinity changes relies on high-quality in-situ salinity observations. Since the beginning of hydrographic observations, over 10 million ocean salinity profiles have been collected by various instruments12. Because of the heterogeneous quality of salinity data in the global archive, there is an increasing demand for a high-quality, error-free, quality-consistent salinity dataset to support relevant scientific research, governmental and non-governmental organizations, industry, fisheries, individuals, and policymakers13,14,15.

In the past decade, salinity gridded products have been compiled by several research groups1,3,16,17,18. These datasets have been widely used for different oceanographic and climatic studies such as the global hydrological cycle19,20, ocean freshwater estimation21,22,23, model evaluation24,25, geostrophic current and freshwater transport estimation26,27,28, as well as essential ocean variables (EOVs) and ocean indicators development15,29. However, Li et al.30 noted substantial differences between these datasets, with quality control (QC) procedures as one of the possible causes. Aiming to achieve a dataset of climate research quality, several research groups were committed to developing a comprehensive automated quality control procedure under the auspices of the International Quality-controlled Ocean Database (IQuOD)31.

The development of an automated quality control system (AutoQC) for salinity is closely linked to the quality control of temperature, as both parameters are almost always measured simultaneously12. Significant progress has been achieved in the development of QC procedures for ocean temperature profile data17,32,33,34,35,36,37,38. Similarly, in the past decades, progress has also been achieved in developing QC systems for salinity profile, each linked to a specific database (Table 1)12,17,18,20,39. For example, the salinity QC systems developed by the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) (namely as WOD-QC37) and by the Met Office Hadley Centre (namely as EN4-QC17,39). These two QC systems deploy automated (AutoQC) and expert manual checks (ExpertQC). The AutoQC procedures in these two systems consist of several checks applied to prove the plausibility of metadata, reported parameter values and derived quantities (date/time, geographical coordinates, platform speed, duplicate cast, depth level inversion, duplicate depth level, high-resolution pairs, variable range, spike, excessive vertical gradient, float track, static stability (density), and others). The manual checking typically involves the removal of outliers and anomalous data through individual profile assessments17,37. The WOD manual-QC (expertQC) also examines unrealistic patterns when constructing maps for the World Ocean Atlas (WOA) and subjectively flagging profiles causing them37. The ExpertQC improves the ability of the system to identify outliers, but is time- and cost-consuming40.

Other QC systems for salinity profile observations include the one developed by the Argo Data Management Team, including real-time QC (Argo-RTQC), real-time adjusted QC, and delayed-mode QC (DMQC) for the Argo products34. The quality-controlled ‘good’ (QC = 1) and ‘possible good’ (QC = 2) Argo data from the Argo Data Management Team are ingested into the WOD and EN4 database17,37. Besides, the ICDC-QC (Integrated Climate Data Center) system developed by the University of Hamburg20 is mainly used to produce the World Ocean Circulation Experiment-Argo Global Hydrographic Climatology based on the quality controlled salinity profiles. Coriolis Ocean dataset for ReAnalysis (CORA-QC41) also developed a hybrid-QC system by Jerome et al.42, which is based on an AutoQC but followed by human validation with ExpertQC, and is mainly used in the Copernicus marine nearly real-time (NRT) and delayed-mode (DM) in-situ salinity dataset.

It has become standard practice in most QC systems to verify profiles against climatological data. For example, the WOD-QC procedure defines the local salinity range by applying criteria of 3 to 5 standard deviations within 5-degree boxes, assuming a Gaussian distribution43. In contrast, the ICDC-QC system20 uses a different method. It employs an adjusted Tukey’s boxplot method that accounts for the skewness in data distribution20. The existing salinity QC algorithms use different thresholds for outlier detection, as well as different sets of quality checks. These differences will impact the respective data products based on observed data filtered by the different QC schemes31,40, introducing the methodological uncertainty in the estimation of climate of such climate indicators like ocean heat content15. Therefore, it is beneficial for this manuscript to first develop a comprehensive automatic QC algorithm for salinity, which is based on the recent developments and improvements of the QC schemes for the seawater parameters. This new AutoQC system, namely the Chinese Academy of Science (CAS) Oceanography Data Center Quality Control system – salinity component (CODC-QC-S), will be also applied in the new database introduced in this paper. Such a QC scheme will be essential for the compilation of a new high-quality and quality-consistent salinity dataset needed to support research activities in hydrology3 and marine/coastal ecosystems44.

To develop a quality control procedure for the high-quality in-situ salinity profiles dataset, we should also understand how the salinity is measured and calibrated as the quality and accuracy of the salinity data depends on the method of salinity measurements. Salinity is a measure of the amount of dissolved matter in the seawater. Its concept and definition experienced several profound changes over time. Originally, the chlorinity of the seawater served as the measure of salinity based on a chemical titration of the water samples collected by means of bottles with bottle depth estimated by the wire length and angle. During the 1960s, the chemical titration was gradually substituted by electronic instruments (salinometers)45. Chemical titration is regarded to be less accurate compared to high-precision electronic salinometers46,47. The modern methods are based on measuring the electrical conductivity of the seawater, which strongly depends on both salinity and temperature and mildly on pressure, with the relationship between the conductivity and these three variables being non-linear. Since 1978, a proxy for true salinity called Practical Salinity has been introduced. All methods of salinity determinations require the reference standard with known salinity – the standard seawater. The IAPSO standard seawater is used to calibrate salinometers in the laboratory (http://www.soest.hawaii.edu/HOT_WOCE/sal-hist-report/3.1.html). Introduced into oceanographic practice in the late 1960s, different types of Conductivity-Temperature-Depth (CTD) profilers provide high-resolution salinity profiles12. However, to achieve high accuracy, the CTD salinities need to be referenced to the salinity of water samples taken at a limited number of levels and analyzed using high-precision laboratory salinometers. Respectively, ship-based CTD salinity profiles are characterized by an order of magnitude higher accuracy than those CTDs installed on autonomous ARGO profiling floats or attached to marine mammals (APB), for which the adjustment to simultaneously obtained bottle samples is impossible. Therefore, Argo float salinity values are prone to instrumental biases due to sensor time drift, fouling, etc48,49. In the deep ocean, the variability of salinity is generally very small25, imposing strict requirements for the accuracy of salinity measurements and thus challenging the performance of QC in the deep ocean. The high-resolution ship-board CTD devices can measure salinity with an accuracy of better than 0.005 g/kg and a resolution of ~0.001 (https://www.seabird.com/profiling/family?productCategoryId=54627473767). In practice, the accuracy of salinity measurements ranges from 0.002 to 0.08, depending on the instrumentation used and the quality standard applied during specific cruises50,51,52,53.

In this study, we introduce a new in-situ ocean salinity dataset named CODC-S (the Chinese Academy of Science (CAS) Oceanography Data Center – Salinity component). Suggested for applications in climate research and operational use, this dataset benefits from the application of a new automatic quality control system for salinity (CODC-QC-S). Both the salinity profiles from the CODC-S database and the new QC algorithm have undergone extensive validation using a high-quality salinity benchmark dataset. We also conducted analyses of global and basin-scale long-term salinity changes using the salinity profiles before and after QC to highlight the robustness of the newly proposed dataset. Here, we note that the CODC-S dataset will adopt a data processing and QC framework similar to that used for the CODC temperature component54 developed by the IAP/CAS (Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences). This framework has been successfully applied in the IAP temperature in-situ data processing (i.e., the CODC-QC-T temperature AutoQC system36) and ocean heat content estimation55,56. Therefore, in this study, the proposed CODC-S dataset, generated with the new salinity AutoQC system (CODC-QC-S), will serve as an extension from the temperature component to the salinity component of the existing CODC dataset54. The CODC-S dataset also complements existing salinity databases such as the WOD12, Ishii16, and EN417. The intercomparison between the salinity databases is vital for addressing the uncertainty sources in estimating ocean salinity changes and the global water cycle, which have not been well-quantified yet57.

Methods

Data sources

The main data sources of CODC-S come from the in-situ salinity profile data in the World Ocean Database (WOD) downloaded in April 2024. We use salinity data from all instruments reporting salinity, including Profiling Float (e.g., Argo profiling floats), Conductivity/Temperature/Depth (CTD), bottles (Ocean Station Data, OSD), moorings (MRB), gliders (GLD), the Autonomous Pinniped Bathythermographs (APB) and others37. Besides, 52,253 non-WOD salinity profiles are included in our study to fill the data-poor regions: the Arctic 1970 to 2005 in-situ CTD data from Bedford Institute of Oceanography, salinity profiles from the Alfred-Wegener-Institute (Bremerhaven, Germany), the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Centre, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans of Canada, the Freshwater Institute, the Institute of Ocean Sciences, and the Maurice-Lamontagne Institute. Additionally, some non-WOD salinity profiles in the Sea around China (e.g., the South China Sea, the East China Sea, the Yellow Sea, and the Western Pacific Ocean) owned by several Chinese institutes are also included in this study58,59,60,61,62,63. In total, there are 11,093,341 salinity profiles with 2,234,827,427 measurements at observed depth levels spanning the period from January 1940 to December 2023.

QC working flows

The CODC-QC-S (CAS-Ocean Data Center (CODC) Salinity Quality Control system) comprises a total of 11 individual quality checks (Table 2). These checks evaluate the acceptable salinity ranges, as well as the vertical structure (shape) of the salinity profile, considering vertical, temporal, and regional variations. The quality control flag for each check is set for salinity values at each observed depth level. The flags are binary: ‘0’ signifies an acceptable (good) value, and ‘1’ indicates a rejected (bad) value. Based on these distinct check flags, the overall quality flag for each observed level is derived. This flag is set to ‘1’ if a salinity value fails at least one distinct check. Otherwise, the overall flag is set to ‘0’ indicating good (accepted) salinity value. Users can rely on the overall quality flag or their own decision based on the individual check values.

The details and parameter settings for each QC check are briefly introduced as follows:

Basic information check

This check proves the validity of each profile’s date, time, and location. For example, the latitude and longitude should be in the range [−83, 90] and [0 360] respectively. The profile location should not be on land. All observations for the profile are flagged if the check fails.

Sample level order check

This test proves whether the sampled levels are reported in increasing order. If level depths are not growing with depth, this observation at this level is flagged.

Local bottom depth check

This check proves whether the deepest sampled level is deeper than the local bottom depth, which is defined according to the latest version of the global 0.5 arc-second resolution digital General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO)64. Since the accuracy of GEBCO bathymetry is not uniform, a tolerance is added following Tan et al.36. Salinity values on levels deeper than the local bottom depth are flagged. An example of this check could be found in the Supplementary Figure 1. However, caution is needed when applying this quality check, as failing the check might be due to errors in coordinates or the digital bathymetry.

Instrument type depth check

Each instrument type is designed to operate within a certain depth/pressure range. If a sample depth falls outside the nominal depth range for the instrument type, the observations beyond the acceptable range are flagged. The ranges are: 0–8000 m for CTD, 0–9000 m for OSD and XCTD, 0–6050 m for PFL, and 0–1200 m for APB. An example of this check could be found in Supplementary Figure 2.

Constant value check

This check identifies salinity profiles with “stuck values”. Such profiles exhibit constant salinity values throughout the whole depth or over an unrealistically thick layer of the water column. An example of this check could be found in Supplementary Figure 3.

Multiple salinity extrema check

This check is aimed to identify profiles with an excessive number of local salinity extremes. The salinity extrema at level k is defined as follows:

Here, M represents the threshold for the salinity extrema magnitude, with the choice based on the instrumental resolution. R is the mean extreme magnitude represented by the maximum allowed instrumental resolution (0.01 g/kg for high-resolution CTD and PFL, 0.05 g/kg for XCTD, low-resolution CTD, Bottle, and others). C/Z denotes the standard deviation of extreme magnitude (Z denotes the depth measurement; C is 25 for CTD, 40 for PFL, and 30 for XCTD, Bottle etc., which are empirical choices). If multiple salinity extremes are detected, all observations of a profile are flagged. This check is not performed in the upper 10 m as some large fluctuations are real features close to the surface, such as in the front water mass. An example of this check can be found in Supplementary Figure 4.

Spike check

This check is to identify the salinity spike. Spike occurs typically due to the malfunction of electronic sensors. The check is done by assessing how far the central salinity measurement at level k deviates from the average of its neighboring depth levels (k−1, k+1), adjusted by the threshold of the absolute difference between those neighbors (S):

Here, S is a depth-dependent spike threshold: S = 0.12 in the upper 1000 m, S = 0.10 between 1000–2000 m; see Supplementary Figure 5). The observations beyond the depth-dependent spike are flagged. Here, it should be noted that once QC-flagged data points are removed, the adjacent data points are reconnected to form a new profile, potentially generating new spikes at these junctions. Therefore, in this check, we will iteratively implement the above judgments over again until no further new spikes are detected in the QCed profile. Supplementary Figure 6 provides an example of this check.

Density inversion check

This check proves whether the water density increases with increasing depth. The density is calculated from salinity and accompanied temperature at the same level using the computationally efficient 75-term expression65. If temperature measurement is not available, this check is not performed. Supplementary Figure 7 shows some examples of this check.

Global crude range check

This check proves if the salinity measurement is grossly in error. The depth-dependent minimum/maximum threshold is determined based on all available salinity profiles from 1940 to 2023 and is set at 0.5% and 99.5% quantiles, respectively. Any value exceeding the overall range is flagged. Specially, this check is not performed in the Red Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, the Persian Gulf, the Black Sea, the Baltic Sea, the Mediterranean Sea, and coastal lines due to their distinct thermohaline structures notably different from that of the open ocean. An example of this check could be found in Supplementary Figure 8.

Global vertical gradient check

This check identifies pairs of depth levels for which the vertical salinity gradient exceeds the overall depth-dependent gradient threshold, which is also determined based on all available salinity profiles from 1940 to 2023. This check is similar to that in Gouretski20, with minor parameter modifications. Similar to the spike check, this check will be iteratively implemented over again until no further threshold-exceed vertical salinity gradients are detected in the QCed profile. An example of this check could be found in Supplementary Figure 9.

Local salinity climatology range check

In addition to the global crude range check, each salinity measurement is checked against the acceptable local climatology range. This local climatology range (hereinafter IAP-S-range) is constructed following the suggestion of two-step thresholding by Yang et al.66: we first perform the preliminary quality control, including checks (1) – (10) aiming to exclude observations which are grossly in error. During the second step, the IAP-S ranges are constructed based on the preliminary QCed data. According to Good et al.31 and Gouretski et al.67, this check represents one of the most effective checks to identify outliers. The construction of the IAP-S local climatology ranges is described in the next section. An example of this check could be found in Supplementary Figure 10.

To evaluate the CODC-QC-S performance, we used the one-time hydrographic dataset obtained from the World Ocean Circulation Experiment (WOCE)68. This dataset is characterized by outstanding data quality due to the strict and uniform quality requirements68,69. The data from each WOCE cruise were subject to the manual expert QC before dissemination to the respective data centers. The high quality and consistency of the WOCE dataset were confirmed through the analysis of differences between distinct cruise lines at cross-over points70. This dataset includes 8,790 CTD salinity profiles and 8,793 Bottle salinity profiles located globally from 1985–1997 (hereinafter ‘WOCE CTD dataset’ and ‘WOCE Bottle dataset), with 98.33% (WOCE CTD) and 96.39% (WOCE Bottle) of all salinity measurements in the upper 2000m ranked as good after the manual expert QC. These high-quality WOCE one-time CTD datasets are used to benchmark and evaluate the CODC-QC-S performance. The True Negative Rate (TNR) is used to assess the ability of a QC algorithm to retain good data (the definition follows Good et al.31):

where \({N}_{{TN}}\) is the number of true negatives, and \({N}_{{FP}}\) is the number of false positives. Here, TNR should be as high as possible. The missing values had been removed before the evaluation.

Local salinity climatology range for CODC-QC-S

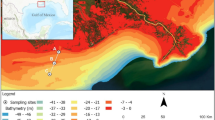

Developing a global ocean salinity profile dataset (i.e., CODC-S) usually depends on a robustness climatological-based automatic QC. However, defining the cut-off for local climatological range in ocean variables is still in debate in the community31. Acceptable ranges for observed variables are commonly established with box-plot methods71 or the mean±3-sigma (i.e., PauTa Criterion), with the latter method assuming a Gaussian distribution. However, the local salinity distribution in the ocean is typically skewed, as illustrated by the skewness maps for two selected depth levels (Fig. 1a,b). Therefore, Gouretski20 suggested to use the modified adjusted boxplot method, which was first introduced by Hubert et al.72 and then improved by Adil et al.73. The latter method defines the local lower fence (\({Lf}\)) and upper fence (\({Uf}\)) (i.e., local salinity range) as a function of three parameters: the salinity interquartile range (IQR), the median coupled (MC) and the skewness (SK) with the coefficient C to achieve the target outlier percentage73:

(a,b) The skewness of salinity (January) distribution in 1o boxes at 15 m and 150 m depth. The maps are based on all quality-controlled WOD18 salinity profiles between 1940 and 2022; (c–f) salinity histograms derived from (a,b) for four selected locations: (A) the south of Gulf Stream, (B) within the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC), (C) within the equatorial east Pacific, and (D) within the Angola Stream. The climatological range thresholds are marked as dash lines in different colors based on different methods. The locations are marked as black stars on maps (a,b). The corresponding salinity profiles are shown in Fig. 2.

Here, C = 1.5 in Adil et al.73, which is a subjective choice and corresponds to ~0.7% outliers for normal distribution. The Q1 and Q3 denote the 25th quantile and the 75th quantile. In a deviation from the original Tukey technique which multiplies the IQR by C = 1.5, the adjusted boxplot method extends or compresses the fences depending on the local skewness parameters SK and MC. Increasing the coefficient C from 1.0 to 2.25 extends the fences and thus reduces the rejection rate and increases the True Negative Rate (TNR) according to benchmark results (Supplementary Table 1). Another way is to set the lower fence and upper fences at fixed quantiles: Tan et al.36 uses the 99% quantile which automatically results in 1% outliers in the data. Comparison of Rejection Rates and True Negative Rates (TNR) using the WOCE benchmark dataset also revealed that the quantile approach with selected fixed quantile thresholds results in a low rejection rate and a high TNR (Supplementary Table 1).

Figures 1, 2 show the comparison of different threshold methods: the Tukey’s boxplot54, the modified adjusted boxplot56, the mean ± 3-sigma (i.e., PauTa Criterion), the 99% quantile30. We found that the mean ± 3-sigma method results in a symmetrical fence because it assumes a Gaussian distribution of the ocean variables. In some cases (e.g., Fig. 2), the mean ± 3-sigma ranges seem too wide compared to the actual observations. In some other cases (e.g., Fig. 2c), the modified adjusted boxplot may effectively identify bad outliers that may be mistakenly identified as good data by different methods. However, the modified adjusted boxplot might face limitations in data-poor regions, as its accuracy relies on local skewness parameters SK and MC. In regions with highly skewed salinity distribution (such as regions A and D in Figs. 1, 2), it seems 99% quantile could reasonably maintain more data that looks realistic than the other methods. Additionally, based on the benchmark evaluation using the WOCE dataset, we found that, if tuning the coefficient C of the Eq. 4, the modified adjusted boxplot73 could give a similar percentage of outliers with the 99% quantile method (when C = 2.0). There is no significant performance difference in data rejection rate and TNR between this approach and the 99% quantile approach (the Supplementary Table 1). Therefore, considering the capacity to deal with the highly skewed data and in the data-poor regions, currently, we decided to use 99% quantile approach for the CODC-QC-S system (i.e., 99.5% quantile for the upper threshold and 0.5% quantile for the lower threshold).

The interpolated salinity profiles (January) at selected 1o boxes correspond to the areas and depth indicated in Fig. 1c–f. The data are based on all WOD salinity profiles between 1940 and 2023 after the QC checks #1-#10. The local climatological range thresholds are marked as dash lines in different colors based on different method: the Tukey’s boxplot71, the modified adjusted boxplot with coefficient C = 1.573, the mean ± 3-sigma (i.e., PauTa Criterion), the 99% quantile36. The locations are marked as black stars on maps in Fig. 1a,b. Here, some data points in a profile are not visible in the full depths because the interpolation is only done using the QCed data (e.g., Panel C). These interpolated data are used to construct the local climatological range fields (IAP-S-range) for the CODC-QC-S.

Within each one-degree box, the salinity in-situ WOD profiles collected between 1940 and 2023 have been utilized to establish the local climatological range fields (hereinafter IAP-S-range). As detailed in previous Local salinity climatology range check section, preliminary quality-controlled salinity profiles are interpolated into 79 standard depths ranging from the surface down to 2000 meters following the method introduced by Reiniger and Ross74. Interpolation is not performed where the gap between two consecutive levels surpasses a threshold (the threshold follows Gouretski20). We didn’t establish the monthly IAP-S-range below 2000 meters because there are limited data in the deep ocean.

At each standard level and for each grid point on a monthly basis, the surrounding profiles are selected within the 555 km radius (follows Li et al.30) to guarantee a sufficient number of profiles even in the data-poor regions. The minimum number of profiles required within the bubble has been determined after some empirical experimenting: minimum of 40 profiles are required above 250 meters, 30 profiles from 250 to 450 meters, 20 profiles from 450 to 1500 meters, and 15 profiles from 1500 to 2000 meters. If the number of profiles collected in a given month does not meet these criteria, additional profiles from neighboring months are included.

Due to the large initial size of the influence bubble, salinity profiles from different water masses might be ingested within the bubble, increasing the overall local salinity range. To more precisely select profiles with characteristics specific for the center of the bubble (e.g., for the analyzed grid-point for which the local salinity limits should be calculated), the following procedure is implemented. For all 1-degree boxes whose centers fall within the influence bubble, salinity monthly mean (M) and salinity standard deviations (σ) are calculated. Then, we retain the data from the boxes in which mean salinity is within the range [Mc ± 0.8*\(\sigma \)c], where Mc and \(\sigma \) are mean salinity and salinity standard deviation for the central box within the bubble, and the coefficient 0.8 chosen after some experiments. The selection of profiles also takes into account topographic barriers, so that profiles isolated by a topographic barrier are not considered. The global 0.5 arc-second resolution digital General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO; 2022 Version) is used to represent the bottom relief64.

Following the above strategies, the upper (Smax) and lower (Smin) climatological thresholds in the IAP-S-range are then defined using 99.5% and 0.5% quantiles based on the data retained after the selection procedure described above. However, the use of constant local thresholds may lead to the exclusion of good ‘extreme’ observations since the global salinity exhibited a significant long-term change over the past 60 years, for example, salinization in the Atlantic Ocean and freshening in the Pacific Ocean because of the intensification of the global hydrological cycle3,30,75, we therefore apply instead time-varying thresholds \({S}_{{\max }}{\prime} \) and \({S}_{{\min }}{\prime} \), with the long-term threshold change represented by a linear trend:

where \({k}_{{mean}}\) is estimated by linearly fitting the IAP salinity monthly gridded product3 in each 1-degree box at each standard level, and \({Year}\) denotes the year of observation (ranging from 1940–2023). The Supplementary Figure 11 shows the spatial distribution of \({k}_{{mean}}\). The Atlantic Ocean shows the highest values, indicating a broad salinization trend, while the Pacific Ocean exhibits the lowest values, corresponding to a significant freshening trend. These patterns agree with the findings of Li et al.30. The final local salinity climatological range field (i.e., IAP-S-range) was constructed on a 1° × 1° grid spanning 79 standard levels from the surface to 2000 m. For each 1-degree box, a spatial nine-point moving average filter was applied to smooth the data.

Figure 3 shows the fields of IAP-S-range for four representative depth layers. The minimum and maximum salinity fields indicate the large-scale salinity patterns, mainly modulated by the surface forcing (i.e., Evaporation minus Precipitation and river runoff) and oceanic transports76. For instance, the near-surface salinity distribution acts as a rain gauge for precipitation minus evaporation over ocean (Fig. 3a,b). For the subsurface ocean, the salinity at 360 m depth is mainly featured by the high-salinity waters of the subtropical gyres and by fresher waters of the North Pacific and Southern Oceans (Fig. 3d,e). Salinity at 1000 and 1500 m levels reveals the low-salinity waters subducting in low- and mid- latitudes1,19 (Fig. 3g–k). The salinity contrast between the salty Atlantic and fresh Pacific is also well seen for all levels, and the saltier Atlantic for 1000 m and 1500 m levels can be attributed to the overflow of the Mediterranean waters77.

The local salinity climatological ranges mirror the spatial variation of salinity (Fig. 3). The largest range of the near-surface salinity is confined to coastal regions and the Arctic Ocean (Fig. 3c), with the latter mainly impacted by the strong terrestrial runoff and the ice melt and ice formation78,79. The Bay of Bengal shows significant salinity variations near the sea surface, which are subject to large terrestrial runoff events with known ocean fronts1. The other regions of the high subsurface salinity variation at 15 m and 360 m levels correspond to the western boundary currents, particularly to the Gulf Stream, being the manifestation of the moving ocean fronts (Fig. 3c,f,i). The fields at 1,000 and 1,500 m show a large salinity variability of >0.6 g kg−1 in the North Atlantic Ocean, corresponding to the salty signature of Mediterranean Outflow Waters (MOW)80 (Fig. 3i,l). To further illustrate the IAP-S-range, the local salinity climatological median field is shown in Supplementary Figure 12.

Data Records

CODC-S dataset81 with global ocean QC-ed salinity data from Jan 1940 to Dec 2023 by applying the CODC-QC-S procedure described above is freely available from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Ocean Data Repository at http://www.ocean.iap.ac.cn/ftp/cheng/CODCv2.1_Insitu_T_S_database/ or https://doi.org/10.12157/IOCAS.20241217.001 (for efficiently reuse in the community, we put the CODC temperature (CODC-T) profiles54 together in the same folder). This dataset includes 1,008 ‘.mat’ (MATLAB format) and 1,008 ‘.nc’ (NetCDF format) monthly files (until Dec 2023), each file corresponding to the specific year and month. The format description is also attached as a ‘README’ document. Additionally, as the primary data source for this study is WOD, therefore, similar with the CODC-T dataset54, most of relevant metadata from the WOD, including WOD-QC flags and data unique IDs, have been maintained. This is essential for enabling future comparisons between CODC-S and WOD (e.g., Section 4). Table 3 list the data format and introduces variables in the data files of CODC-S.

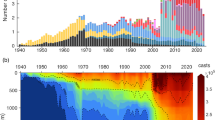

Figures 4, 5 show some basic statistical information about the data counts and profile geographical location in the CODC-S. For the entire dataset, the total number of salinity observations increases gradually over time but decreases with depth (Fig. 4). The majority of the salinity profiles come from the three main instrumentation types: 1) hydrographic bottle casts (e.g., the OSD instrumentation type), 2) the CTD casts, and 3) the autonomous Argo floats (PFL type). The OSD profiles contribute 23% of all salinity profiles but exhibit a strong geographical bias to the Northern Hemisphere (Fig. 5b). A small fraction of the OSD profiles come from the low-resolution CTD profiles47. Since the end of the 1960s, when electronic profilers were introduced in oceanographic practice, the CTD profiles currently amount to ~1.32 million profiles (13.07% of all profiles). After the 2000s, the array of core-Argo autonomous floats started to provide salinity profiles for the upper 0–2000 m, dramatically improving global salinity sampling (Figs. 4b, 5e). The Argo salinity profiles comprise 24.70% of the entire CODC-S dataset. The four other instrumentation types are represented by APB, MRB, UOR, and DRB salinity profiles, each contributing 6.16%, 6.38%, 1.74% and 1.17% of profiles, respectively. These instruments are characterized by a regional geographical scope. Below the core-Argo float maximum depth of 2000m, the number of salinity observations drops significantly.

Technical Validation

CODC-QC-S systems validations

Here, we will first validate the performance of the proposed QC system. Using the WOCE benchmark dataset, we find the TNR of 99.93% and 99.24% for the WOCE CTD and the WOCE Bottle dataset, respectively. The flags are mainly attributed to the local salinity climatological range check. In comparison, ICDC-QC scheme developed by Gouretski20 (improved version in November 2024) has a similar TNR of 99.91% (WOCE CTD dataset) and 99.8% (WOCE Bottle dataset) with the local salinity climatological ranges defined by the modified adjusted box-plot method, this is because by tuning the Coefficient C of the modified adjusted box-plot72, ICDC-QC can give the similar percentage of outliers like the CODC-QC-S (see Supplementary Table 1). This result indicates that CODC-QC-S can effectively retain good data.

We also note that the WOCE Bottle and CTD benchmark dataset have a tiny fraction (~1–3%) of salinity values with WOCE flags indicating bad or likely bad data. Only 1.09% (WOCE CTD dataset) and 5.34% (WOCE Bottle dataset) of these values were detected as outliers by the CODC-QC-S. Similarly, these values are 1.26% and 3.65% for ICDC-QC. The failure in detection is due to the dominant amount (~65%) of hidden outliers that fall within the magnitude of the natural variability: the salinity differences with the adjacent depth layers are typically smaller than 0.05 (in average) below the halocline, which are much smaller than the preset thresholds in all the QC checks. This result indicates a potential limitation of the CODC-QC-S. Nevertheless, note that we only have a tiny fraction of benchmark bad data, the evaluation of the CODC-QC-S performance of removing bad data would benefit through the comparison with other benchmarking datasets that contain a large amount of bad data that underdo the expert QC (e.g., similar to the QuOTA dataset65 for temperature profiles), but no other manually validated salinity datasets were available for us at present.

For further assessment of the CODC-QC-S performance, we checked the ability of outlier detection by using the Argo grey list (the grey list information is sourced from https://argo.ucsd.edu/data/) as another possible alternative. We compared the rejection rate of the Argo grey list floats and non-grey list floats and found the Argo grey list floats exhibited systematic errors or other types of malfunctions, which contribute to the higher rejection rate (Fig. 6). This is also illustrated by Fig. 12c showing a higher rejection rate for some specific Argo floats. Similar results could be found in the QCed data in the WOCE benchmark dataset, where the rejected data can be attributed to some specific cruise lines (Supplementary Figure 13). We noted that a minor fraction of non-grey list floats also exhibits a much higher rejection rate (for instance, the float with ID = 3902185 in Fig. 6), and we believe that the above examples show the ability of CODC-QC-S to serve as a valuable tool in data quality monitoring in the future.

The percentage (%) of salinity outliers for the randomly selected 60 Argo floats (with 30 floats from the Argo grey list) after the application of the CODC-QC-S. The Argo profiles for the time period 2015 to 2020 are used. The float ID numbers are shown in the right panel, with non-grey list floats shown ordered in blue and grey list floats ordered in orange. The dashed line denotes the overall PFL rejection rate.

We also used some randomly selected real-time PFL (Argo) salinity profiles to further evaluate the CODC-QC-S performance. The raw real-time Argo profiles have not undergone rigorous delayed-mode QC at Argo Data Assembly Centers (DAC) and so include a considerable fraction of outliers (Fig. 7a,b). Data with quality issues and gross errors (e.g., spikes, extreme values, constant values, unrealistic variability, etc.) can be successfully identified as outliers by the CODC-QC-S, with the similar performance in different periods obtained by different instrument types (Supplementary Figure 14). Accordingly, the application of the CODC-QC-S reduces the overall salinity standard deviation at depth levels compared to the raw data (Fig. 7c).

Results of the application of the CODC-QC-S to the randomly selected 4,000 real-time Argo data from the year 2022: (a) profiles before QC (No QC), (b) after CODC-QC, (c) The mean salinity profile (solid line) and standard deviation (dashed line) for the original and quality-controlled data based on the profiles in (a,b).

Furthermore, we checked the regional CODC-QC-S performance in two randomly selected boxes. Figure 8 shows the mean and standard deviation of the salinity anomaly profiles (relative to 2008–2012 climatology) within two selected boxes before and after CODC-QC-S. The data before CODC-QC-S indicate the raw data including a lot of unrealistic variation (see Fig. 8b,e). However, the data after CODC-QC show significantly fewer anomalies (Fig. 8a,d). Several specific examples of the data rejection through the CODC-QC-S are provided in the Supplementary Information of Supplementary Figures 1–10. We conclude that the application of the CODC-QC-S leads to the reduction of the overall standard deviation and to smooth profiles of the standard deviation over depth. In addition, we also note that the application of the quality control procedure has an impact on the mean salinity profile (Fig. 8a,d).

(a,d) The box-averaged QCed & noQCed salinity anomaly profiles (relative to 2008–2012 climatology by Cheng et al.3) with one standard deviation envelope in two different regions. Here, the retained profiles after the application of CODC-QC-S and the profiles without performing any QC are shown. (b,c,e,f) are corresponding individual profiles before & after the application of the CODC-QC-S. Here, the locations of Box A and Box B are marked as black squares in Fig. 13b.

Dataset (CODC-Salinity) validations

Individual data points (profile) validation

Here, we provided the CODC-S dataset validation from the perspective of data outliers statistics from the assessment based on over 11 million individual QCed salinity profiles from 1940 to 2023 (see Section 2.1 for the data source). The total rejection rates were defined as the percentage of the number of observations flagged as bad to the total number of observations. The gross errors and missing values (e.g., 99999, −99999, 99, −99, etc.) were excluded from our statistics. For the entire CODC-S dataset, which includes OSD, CTD, PFL, APB, MRB, DRB, and GLD instrumentation types, the overall rejection rate is 2.27% for 2,234,189,022 measurements. The yearly rejection rate decreased over time, with data collected before the 1990s generally exhibiting higher rejection rates compared to data obtained after the 2000s (red line in Fig. 9b). The decreasing rejection rate is primarily due to the general improvement of instrument accuracy/precision over time46,53,82. The result shows a homogeneous overall rejection rate (~3.5%) with depth (black line in Fig. 9c), with only some regionally deployed instrument groups showing a higher-than-average rejection rate (Fig. 9c). Among the distinct instrument groups, the MRB, PFL, and Glider data exhibit the lowest rejection rate (less than 2%), being superior in data quality compared to APB, DRB and old Nansen casts. The lower rejection rate of PFL and Glider can be explained because only good data provided by the data originator were included into WOD (see the Introduction section).

(a) The overall rejection rate after QC for each salinity instrument group for three different QC flags schemes: CODC-QC-S (this study), WOD-QC observed level flag (only use Salnity_WODflag>0, indicates as ‘level’ here), and WOD-QC observed level flag & entire cast flag (use Salinity_WODflag>0, Salinity_WODprofileflag>0, Depth_WODflag>0; indicates as ‘level & cast’ here). (b) is the same as (a), but as a function of year. (c) is the rejection rate after CODC-QC-S as a function of the depth. The definition of WOD-QC flag37 can be found via https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/data/oceans/woa/WOD/DOC/wodreadme.pdf (in Table 12).

Specifically, the APB data have the highest overall rejection rate of 7.39% among all instrumental types. The percentage of outliers steadily increases with depth below 500 m (Fig. 9a,c). We note that mammals less frequently dive deeper than 500 m82, and the APB measurements can be strongly influenced by the behaviors of marine animals53, the thermal mass errors in the tags83 and the errors in geographical position84. Our results are also consistent with Boehlert et al.82 who reported the high outlier percentage for APB data.

Figure 10 shows the rejection rate versus depth and time for four main instrumental types. The progressive improvement in data quality is most clearly seen in OSD profiles. The highest percentage in the upper 500 m during the 1940s is mainly due to the erroneous positions of Nansen casts often reported during the Second World War (Fig. 11a). The CTD profiles are characterized by higher rejection rates before 1980 (Fig. 10b), which is partly due to the gross salinity errors at the initial stage of CTD implementation, and the same as below 2500 m, which is partly characterized by unrealistic vertical gradients and spikes at the final stage of CTD downcast before it hit the bottom (Fig. 11b). The quality of the PFL data improves significantly after 2005 indicating issues with salinity sensors during the initial stage of the Argo program before 2005 (Figs. 10d, 11c). The increased rejection rate after ~2020 (Figs. 10d, 11c) is due to a larger fraction of real-time Argo data, which have not undergone delayed-mode quality control (DMQC) at data acquisition centers. A higher rejection rate for APB data in 2004–2006 is linked to some gross errors (Fig. 11e). A high percentage of DRB outliers in 2013 is connected to the wrong geographic coordinates on land (Fig. 11f). The local salinity climatology range check results in the largest outlier percentages compared to other checks (Fig. 11).

Yearly percentage of data rejected by each quality check for six main instrumentation types: (a) OSD (Bottle), (b) CTD, (c) PFL, (d) GLD, (e) APB, and (f) DRB. Black dashed line shows the yearly rejection rate based on all distinct checks (this value is less than the sum of the individual check percentages because some measurements are flagged by several distinct checks in parallel).

Finally, Fig. 13 provides spatial rejection rate maps for four main instrumentation types: CTD, OSD, PFL, and APB. The three most accurate instrumentation types (OSD, CTD, and PFL) are characterized by low outlier percentages (less than 2% on average) for most regions. A somewhat higher percentages are found within the regions of coastal upwelling (tropical Pacific), marginal seas (e.g., the Japan Sea, the Red Sea), high energetic zones (e.g., Kuroshio, Antarctic Circumpolar Current, Agulhas Return Current), and coastal regions, suggesting the need for further adjustment of the local salinity climatology range.

Additionally, Fig. 9a–b and the Supplementary Figure 15 show the rejection rate for WOD-QC flags. According to the WOD user manual37, two types of WOD-QC flags are provided: QC flags for each observed level (Salinity_WODflag) and QC flags for the entire cast (Salinity_WODprofileflag). The latter flag is based on both AutoQC and ExpertQC. The ExperQC flag is set when the profiles are selected for NOAA climatology products37 (e.g., WOA23). Our results indicate a significant difference in the impact of these two flags: the first flag is less strict than the second one. Comparisons with the results of the CODC-QC-S validation (red lines in Fig. 9b), we find that the rejection rate of CODC-QC-S falls between the rejection rates suggested by the two WOD-QC flags. We noted that the discrepancy in the rejection rate between CODC-QC-S and WOD-QC might be due to the distinctions in the threshold definition of QC checks, additional QC checks, and entire profile QC flagging strategy (see Supplementary Table 2 in the Supplementary Information). However, intercomparing the performance of different salinity QC checks is more complicated due to the different QC standards and multi-faced adoption in different cases. Currently, IQuOD (IQuOD International Quality-Controlled Ocean Database)85 has started a task team to identify the best-practices salinity AutoQC checks, and we believe the above investigation could contribute to this comprehensive investigation in the future.

To conclude, the data quality of salinity in CODC-S is time-, depth-, instrument-, and regional-dependent (Figs. 9–12), which is mostly linked to the changes in measuring techniques (e.g., sensors, and recording systems). Specifically, the bottle salinities of water samples (OSD instrumentation type), determined through chemical titration in early years46 have been gradually replaced by salinities determined utilizing salinometers45 which still provide the most accurate salinity measurements often used as reference. Besides, there has been a shift from the manual data recording (for old bottle data) to automatic recording by shipboard CTDs or Argo floats. Compared to salinity titration for old Nansen casts, the modern instrumentation determines salinity by measuring the electrical conductivity of the sea water, markedly improving the data quality (as indicated in Section 1).

Climatology validation

Another possible way to illustrate the CODC-S data quality is to inspect spatial fields of salinity standard deviation, calculated by the standard deviation among all available observations in each grid box, which largely represents the local variability of the ocean salinity. These fields based on unvalidated data typically exhibit spikes, “bullseye (red blobs)”, or other unphysical salinity variations. Figure 13 shows the 1-degree gridded fields of the salinity standard deviation at four selected levels (20 m, 700 m, and 1000 m). Generally, compared with the no-QCed data, the maps after applying the CODC-QC-S depict the well-known large-scale global salinity variation patterns with areas of high standard deviation corresponding to high-energetic regions of western boundary currents, Antarctic Circumpolar Current, and the equatorial zone. We note that these patterns also agree with the standard deviation map of the World Ocean Atlas 2023 (WOA2318) where the original salinity data undergone automatic WOD-QC and a rigorous manual QC check (Fig. 13c,f,i) and thus can be regarded as a benchmark climatology dataset. We believe that a high degree of consistency with WOA23 fields indicates the success of the CODC-QC-S scheme in removing the outliers without performing any further manual/expert QC. We also note that these patterns can be explained by previous studies1,3 of ocean thermohaline variability. The same fields, but based on non-validated data exhibit numerous spots of high standard deviation (second columns of Fig. 13). We also note that the fields based on the data retained after the application of the WOD observed level flag (‘Salinity_WODflag’) only still exhibit some unrealistic patterns in the upper layers and larger standard deviation than CODC-QC-S (see Fig. 14).

The standard deviation (the first column) of salinity measurements (units: g/kg) in each 1° by 1° grid in the CODC-S dataset with a spatial nine-points move median at different represented depth: 20 m, 300 m, and 1000 m: (The first column) using all QC passed data from CODC-QC-S (flag = 0); (The second column) using all raw data without performing any QC (the gross error data and missing values like ‘99.99 or 9999’ are removed to avoid absurd results). In comparison, the standard deviation of the statistical mean of salinity from WOA2318 (‘All years’ climatology) with a spatial nine-points move median are shown in the last column.

The same as Fig. 13, but for the comparison of the standard deviation of salinity measurements (units: g/kg) using all CODC-QC-S-ed data (flag = 0) (left panel) and the WOD-QC-ed (Salinity_WODflag = 0) (middle panel). The difference between the left panel and the middle panel is shown in the right panel.

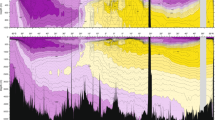

Time series validation

Another validation method is to check the impact of the QC on the estimation of the salinity changes before & after QC. As ocean salinity has changed at various spatial and temporal scales in response to natural variability and external forcings13,86, the erroneous salinity profiles, if not properly dealt with, will ultimately impact the estimation of the salinity changes. To test the performance of CODC-S dataset on long-term salinity change estimates, we compare the estimated sea surface salinity (SSS) and 0–2000 m averaged salinity (S2000) changes at global scale and in different ocean basins using two datasets: CODC-S with CODC-QC-S applied and the same in-situ data without CODC-QC-S applied (i.e., NoQC; but some crude QC process is still applied to remove some crude values, for example, removing the salinity measurements less than 0 g/kg and larger than 45 g/kg). The two sets of data are then processed separately with the same data processing procedure as described in Cheng et al.3, e.g., the same vertical interpolation and gap-filling methods, as well as removing the duplicated profiles following the definition by Song et al.87.

The Global, Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian SSS and S2000 time series before and after QC are shown in Fig. 15. The most visible difference before and after QC is the salinity variability. After QC, the standard deviation of the detrended salinity time series from 1960 to 2023 is reduced by ~25% for global SSS (0.0191 g kg−1 before QC, 0.0141 g kg−1 after QC), by ~75% for Global S2000 (0.0059 g kg−1 before QC, 0.0015 g kg−1 after QC). For example, the ‘large jumps’ seen in the S2000 time series before QC during the early 1980s might be caused by gross salinity errors (e.g., limitation of sensors or conductivity probes) during the initial stage of CTD implementation88,89,90. However, these ‘jumps’ disappeared after applying the CODC-QC-S. The smaller salinity variability after QC is likely more physically tenable because the salinity change over the global scale is associated with the surface net freshwater flux, which can be used as a constraint for salinity variability. A global change of 0.0059 g kg−1 in S2000 corresponds to a sea-level change of about 300 mm (assuming the freshwater input/outputs in the 0–2000 m layer), which is far greater than the variation of total sea level revealed by altimetry data (from the University of Colorado https://sealevel.colorado.edu/). Independent measurement of ocean mass change by [Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE)]. Watkins et al.91 suggests a water mass variation of 1.25e + 12 m3 (equal to a sea level variation of ~2.75 mm) from 2002 to 2023, corresponding to a S2000 variability of 0.00005 g kg−1. For comparison, the S2000 variation after QC is 0.0011 g kg−1 after 2002, closer to the GARCE result than before QC (0.0017 g kg−1). These physical considerations suggest that QC can reduce spurious variability and improve the quality of salinity data.

The reconstructed SSS (left) and 0–2000 m (right) salinity time series before (dashed grey line) and after (solid colored line) QC for Global, Pacific, Atlantic and Indian oceans, separately. The dashed lines represent results before QC (NoQC), and the solid lines show after CODC-QC-S. The anomalies are calculated relative to the 2000–2015 climatology.

The reduction of variability after QC can be found in all ocean basins. For example, before QC, there were big Atlantic, Indian and Pacific S2000 salinity anomalies of >0.03 g kg−1 in the early 1980s and a spike of Atlantic S2000 of ~ 0.02 g kg−1 in 2005, drops of Indian S2000 of 0.01~0.02 g kg−1 after 2020, which are all too big and non-physical because of the erroneous in situ data. Such anomalous signals disappeared after QC/adjustment (Fig. 15). For basin means, the standard deviations are reduced from 0.0253 (Pacific SSS), 0.0068 (Pacific S2000), 0.0359 (Atlantic SSS), 0.0066 (Atlantic S2000), 0.0378 (Indian SSS), 0.0115 (Indian S2000) before QC to 0.0181 (Pacific SSS), 0.0015 (Pacific S2000), 0.0291 (Atlantic SSS), 0.0030 (Atlantic S2000), 0.0313 (Indian SSS), 0.0025 (Indian S2000) g kg−1 after QC (Fig. 15). Note that the S2000 estimate always shows a bigger impact of QC than SSS because of sparser data in the sea subsurface than in the near-surface, so the erroneous measurements can impact broader areas over time and space associated with the spatial interpolation approach.

The long-term trends of salinity change can also be influenced by the QC method. Because of the amplification of the global water cycle, the Pacific Ocean has been getting fresher, and the Atlantic Ocean has been getting saltier1,3,19,92. Such contrasting trends have been identified as robust even based on data without QC (Fig. 15). However, the long-term (1960–2023) trends can be largely impacted by QC, changing from 0.19 ± 0.05 (Atlantic SSS), 0.024 ± 0.019 (Atlantic S2000), −0.09 ± 0.04 (Pacific SSS), −0.018 ± 0.021 (Pacific S2000) g kg−1 century−1 before QC to 0.09 ± 0.04 (Atlantic SSS), 0.020 ± 0.009 (Atlantic S2000), −0.09 ± 0.02 (Pacific SSS), −0.015 ± 0.004 (Pacific S2000) g kg−1 century−1 after QC. The linear trend is calculated by the ordinary least square regression with a 90% confidence interval shown (accounting for the reduction in degree of freedom). On a global average, GARCE data derived a trend in ocean salinity of about −0.004 g kg−1 century−1 from 2002–2023 for the upper 2000 m, assuming the freshwaters are all input there, nearly identical to the global S2000 trend from 1960 to 2023 after QC (−0.004 ± 0.002 g kg−1 century−1). However, the short-term global S2000 after 2000 shows an increasing trend, opposite to the expected impact of freshwater input into the ocean due to land ice melting, which is likely associated with the Argo data drift93,94.

In summary, this test suggests a high-quality and outliers-minimized global ocean salinity profiles dataset and its well-tuned salinity QC system are a basis for a more accurate estimate of global and regional salinity changes. Consequently, the robust estimate of long-term salinity trends is a basis for quantifying the trends of water cycle amplification1,3. However, even after our QC, the magnitude of salinity variability is still larger than the results derived from GRACE data, indicating either further refinements are needed for the QC scheme, or there are other sources of errors in salinity data.

Usage Notes

The development of a quality-controlled global hydrographic database is the main goal of the international IQuOD initiative (International Quality-controlled Ocean Database)85. The joint efforts of several international teams had resulted in producing the first version of this database with quality flags for temperature profiles. This study may be considered as a further contribution to the IQuOD joint effort, including contributing to the development of the IQuOD salinity database and identifying the best practices in salinity QC. We also believe that the assessment methodologies used in this study could serve as a preliminary salinity QC performance evaluation framework for future use.

Code availability

Scripts for loading the CODC-S dataset into MATLAB, as well as the codes to process the dataset for the manuscript figures, are provided in the README document via http://www.ocean.iap.ac.cn/ftp/cheng/CODCv2.1_Insitu_T_S_database/. We also provide access to the codes for interpolation methods for their specific purposes via http://www.ocean.iap.ac.cn/.

References

Durack, P. J. & Wijffels, S. E. Fifty-year trends in global ocean salinities and their relationship to broad-scale warming. J Climate 23, 4342–4362 (2010).

Levang, S. J. The response of ocean salinity patterns to climate change: implications for circulation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2019).

Cheng, L. et al. Improved estimates of changes in upper ocean salinity and the hydrological cycle. J Climate 2020, 10357–10381 (2020).

Rabe, B., Johnson, H. L., Münchow, A. & Melling, H. Geostrophic ocean currents and freshwater fluxes across the Canadian polar shelf via Nares Strait. J Mar Res 70, 603–640 (2012).

Li, G. et al. Increasing ocean stratification over the past half-century. Nat Clim Change 10, 1116–1123 (2020).

Haumann, F. A. et al. Sea-ice transport driving Southern Ocean salinity and its recent trends. Nature 537, 89–92 (2016).

Freeland, H. J. Evidence of change in the winter mixed layer in the Northeast Pacific Ocean: a problem revisited. Atmos Ocean 51, 126–133 (2013).

Ranasinghe, R. et al. Climate change information for regional impact and for risk assessment. In climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Ruane, A. C. et al. The climatic impact‐driver framework for assessment of risk‐relevant climate information. Earths Future 10, e2022EF002803 (2022).

Tan, Z., von Schuckmann, K., Cheng, L. & Speich, S. in EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts. EGU-3662.

Pecuchet, L., Törnroos, A. & Lindegren, M. Patterns and drivers of fish community assembly in a large marine ecosystem. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 546, 239–248 (2016).

Boyer, T. P. et al. World Ocean Database 2018. A. V. Mishonov, Technical Editor, NOAA Atlas NESDIS 87 (2018).

Bindoff, N. L. et al. Changing Ocean, Marine Ecosystems, and Dependent Communities. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. Report No. 1009157973 (2019).

IPCC. Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (Cambridge Univ. Press 2021).

Cheng, L. et al. New record ocean temperatures and related climate indicators in 2023. Adv Atmos Sci, 1–15 (2024).

Ishii, M. et al. Accuracy of global upper ocean heat content estimation expected from present observational data sets. Sola 13, 163–167 (2017).

Good, S. A., Martin, M. J. & Rayner, N. A. EN4: Quality controlled ocean temperature and salinity profiles and monthly objective analyses with uncertainty estimates. J Geophys Res-Oceans 118, 6704–6716 (2013).

Reagan, J. R. et al. World Ocean Atlas 2023, Volume 2: Salinity. A. Mishonov, Technical Ed. NOAA Atlas NESDIS 90. https://doi.org/10.25923/70qt-9574 (2024).

Helm, K. P., Bindoff, N. L. & Church, J. A. Changes in the global hydrological‐cycle inferred from ocean salinity. Geophys Res Lett 37 (2010).

Gouretski, V. World Ocean Circulation Experiment – Argo global hydrographic climatology. Ocean Science 14, 1127–1146 (2018).

Fournier, S. et al. Sea surface salinity as a proxy for Arctic Ocean freshwater changes. J Geophys Res-Oceans 125, e2020JC016110 (2020).

Palmer, M. D. et al. Adequacy of the Ocean Observation System for Quantifying Regional Heat and Freshwater Storage and Change. Front Mar Sci 6 (2019).

McDonagh, E. L. & King, B. A. Oceanic fluxes in the South Atlantic. J Phys Oceanogr 35, 109–122 (2005).

Jensen, T. G. et al. Modeling salinity exchanges between the equatorial Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal. Oceanography 29, 92–101 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. How well do CMIP6 and CMIP5 models simulate the climatological seasonal variations in ocean salinity? Adv Atmos Sci 39, 1650–1672 (2022).

Dong, S., Goni, G. & Bringas, F. Temporal variability of the South Atlantic meridional overturning circulation between 20 S and 35 S. Geophys Res Lett 42, 7655–7662 (2015).

Manta, G. et al. The South Atlantic meridional overturning circulation and mesoscale eddies in the first GO‐SHIP section at 34.5 S. J Geophys Res-Oceans 126, e2020JC016962 (2021).

Zheng, H. et al. An observation‐based estimate of Atlantic meridional freshwater transport. Geophys Res Lett 51, e2024GL110021 (2024).

Forster, P. M. et al. Indicators of global climate change 2022: Annual update of large-scale indicators of the state of the climate system and the human influence. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 15, 2295–2327 (2023).

Li, G. et al. A global gridded ocean salinity dataset with 0.5° horizontal resolution since 1960 for the upper 2000 m. Front Mar Sci 10, 1108919 (2023).

Good, S. et al. Benchmarking of automatic quality control checks for ocean temperature profiles and recommendations for optimal sets. Front Mar Sci 9, 1075510 (2023).

Bushnell, M. Quality assurance/quality control of real-time oceanographic data. OCEANS 2016 MTS/IEEE Monterey. IEEE (2016).

Castelao, G. P. A framework to quality control oceanographic data. J Open Source Softw 5, 2063 (2020).

Wong, A., Keeley, R. & Carval, T. Argo quality control manual for CTD and trajectory data (2020).

Mieruch, S. et al. SalaciaML: A deep learning approach for supporting ocean data quality control. Front Mar Sci 8, 611–742 (2021).

Tan, Z. et al. A new automatic quality control system for ocean profile observations and impact on ocean warming estimate. Deep Sea Res 1 Oceanogr Res Pap 194, 103961 (2023).

Garcia, H. E. et al. World Ocean Database 2023 User’s Manual. A.V. Mishonov, Technical Ed., NOAA Atlas NESDIS 98, pp 129. (2024).

Zhang, B. et al. Developing big ocean system in support of Sustainable Development Goals: challenges and countermeasures. Big Earth Data 5, 557–575 (2021).

Ingleby, B. & Huddleston, M. Quality control of ocean temperature and salinity profiles: historical and real-time data. J Marine Syst 65, 158–175 (2007).

Tan, Z. et al. Quality control for ocean observations: From present to future. Sci China Earth Sci 65, 215–233 (2022).

Szekely, T., Gourrion, J., Pouliquen, S. & Reverdin, G. The CORA 5.2 dataset for global in situ temperature and salinity measurements: data description and validation. Ocean Science 15, 1601–1614 (2019).

Gourrion, J. et al. Improved Statistical Method for Quality Control of Hydrographic Observations. J Atmos Ocean Tech 37, 789–806 (2020).

Garcia, H. E. et al. World Ocean Database 2018: User’s Manual. A.V. Mishonov, Technical Ed., NOAA, Silver Spring, MD (2018).

Van der Stocken, T. et al. Mangrove dispersal disrupted by projected changes in global seawater density. Nat Clim Change 12, 685–691 (2022).

Tabata, S. On the accuracy of sea‐surface temperatures and salinities observed in the northeast pacifie ocean. Atmos Ocean 16, 237–247 (1978).

Warren, B. A. Nansen-bottle stations at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Deep Sea Res 1 Oceanogr Res Pap 55, 379–395 (2008).

Gouretski, V., Cheng, L. & Boyer, T. On the consistency of the bottle and CTD profile data. J Atmos Ocean Tech 39, 1869–1887 (2022).

Wong, A. P., Johnson, G. C. & Owens, W. B. Delayed-mode calibration of autonomous CTD profiling float salinity data by θ–S climatology. J Atmos Ocean Tech 20, 308–318 (2003).

Bordone, A. et al. XBT, ARGO float and ship-based CTD profiles intercompared under strict space-time conditions in the Mediterranean Sea: Assessment of metrological comparability. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 8, 313 (2020).

Joyce, T. et al. Observations of the Antarctic polar front during FDRAKE 76: a cruise report. WHOI-76-74, 154pp (1976).

Mizuno, K. & Watanabe, T. Preliminary results of in-situ XCTD/CTD comparison test. Journal of Oceanography 54, 373–380 (1998).

Pellerano, F. A., Horgan, K. A., Wilson, W. J. & Tanner, A. B. in IGARSS 2004. 2004 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium. 774–776 (IEEE).

Siegelman, L. et al. Correction and Accuracy of High- and Low-Resolution CTD Data from Animal-Borne Instruments. J Atmos Ocean Tech 36, 745–760 (2019).

Zhang, B. et al. CODC-v1: a quality-controlled and bias-corrected ocean temperature profile database from 1940–2023. Scientific Data 11, 666 (2024).

Cheng, L. et al. IAPv4 ocean temperature and ocean heat content gridded dataset. Earth Syst Sci Data 2024, 3517–3546 (2024).

Cheng, L. et al. Record High Temperatures in the Ocean in 2024. Adv Atmos Sci, 1–18 (2025).

Liu, C., Liang, X., Ponte, R. M. & Chambers, D. P. “Salty Drift” of Argo Floats Affects the Gridded Ocean Salinity Products. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans (2024).

Wang, X., Wang, C. & Liu, C. A dataset of profile observation on three-anchor buoy integrated observation platform of the East China Observation station in 2018–2019. Science Data Bank. https://doi.org/10.11922/sciencedb.926 (2019).

Jia, S., Liu, C. & Wang, C. A dataset of temperature, salinity and depth profile of sea water based on No.6 Buoy of the East China Observation Station during 2014–2015. Science Data Bank. https://doi.org/10.11922/sciencedb.931 (2019).

Meng, Z. et al. A dataset of benthic environmental parameters in the Yellow Sea (2007–2009). Science Data Bank. https://doi.org/10.11922/sciencedb.554 (2018).

Hu, Z. et al. Oceanographic data collected within the eastern equatorial Indian Ocean by JAMES during December 2019‒February 2020. Science Data Bank. https://doi.org/10.11922/sciencedb.01136 (2021).

Chang, Y. et al. The ocean dynamic datasets of seafloor observation network experiment system at the South China Sea. Science Data Bank. https://doi.org/10.11922/sciencedb.823 (2019).

Xu, C. et al. 2009-2012 South China Sea section scientific CTD CTD data sets. Science Data Bank. https://doi.org/10.11922/sciencedb.41 (2015).

Tozer, B. et al. Global bathymetry and topography at 15 arc sec: SRTM15+. Earth and Space Science 6 (2019).

Roquet, F., Madec, G., McDougall, T. J. & Barker, P. M. Accurate polynomial expressions for the density and specific volume of seawater using the TEOS-10 standard. Ocean Modelling 90, 29–43 (2015).

Yang, J., Rahardja, S. & Fränti, P. in Proceedings of the international conference on artificial intelligence, information processing and cloud computing. 1–6.

Gouretski, V. et al. A consistent ocean oxygen profile dataset with new quality control and bias assessment. Earth Syst Sci Data 16, 5503–5530 (2024).

King, B. A., Firing, E. & Joyce, T. M. Shipboard observations during WOCE. Vol. 77 (Elsevier, 2001).

Gouretski, V. & Koltermann, K. P. WOCE global hydrographic climatology. Berichte des BSH 35, 1–52 (2004).

Gouretski, V. & Jancke, K. Systematic errors as the cause for an apparent deep water property variability: global analysis of the WOCE and historical hydrographic data. Prog Oceanogr 48, 337–402 (2000).

McGill, R., Tukey, J. W. & Larsen, W. A. Variations of box plots. The american statistician 32, 12–16 (1978).

Hubert, M. & Vandervieren, E. An adjusted boxplot for skewed distributions. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis 52, 5186–5201 (2008).

Adil, I. H. & Irshad, A. R. A modified approach for detection of outliers. Pakistan Journal of Statistics and Operation Research 11, 91–102 (2015).

Reiniger, R. & Ross, C. A method of interpolation with application to oceanographic data. Deep Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts 15, 185–193 (1968).

Zhu, C. & Liu, Z. Weakening Atlantic overturning circulation causes South Atlantic salinity pile-up. Nat Clim Change 10, 998–1003 (2020).

Yu, L. A global relationship between the ocean water cycle and near‐surface salinity. J Geophys Res-Oceans 116 (2011).

Jordà, G. et al. The Mediterranean Sea heat and mass budgets: Estimates, uncertainties and perspectives. Prog Oceanogr 156, 174–208 (2017).

Li, H. & Fedorov, A. V. Persistent freshening of the Arctic Ocean and changes in the North Atlantic salinity caused by Arctic sea ice decline. Clim Dynam 57, 2995–3013 (2021).

Rudels, B. & Carmack, E. Arctic ocean water mass structure and circulation. Oceanography 35, 52–65 (2022).

Potter, R. A. & Lozier, M. S. On the warming and salinification of the Mediterranean outflow waters in the North Atlantic. Geophys Res Lett 31 (2004).

Zhu, Y. et al. CODC-v2 global ocean in-situ profile observational dataset. Chinese Academy of Sciences Oceanographic Science Data Center. https://doi.org/10.12157/IOCAS.20241217.001 (2024).

Boehlert, G. W. et al. Autonomous pinniped environmental samplers: using instrumented animals as oceanographic data collectors. J Atmos Ocean Tech 18, 1882–1893 (2001).

Mensah, V. et al. A correction for the thermal mass–induced errors of CTD tags mounted on marine mammals. J Atmos Ocean Tech 35, 1237–1252 (2018).

Welch, D. W. & Eveson, J. P. in Electronic Tagging and Tracking in Marine Fisheries: Proceedings of the Symposium on Tagging and Tracking Marine Fish with Electronic Devices, February 7–11, 2000, East-West Center, University of Hawaii. 369–383 (Springer).

Cowley, R. et al. International Quality-Controlled Ocean Database (IQuOD) v0.1: the temperature uncertainty specification. Front Mar Sci 8, 689–695 (2021).

Gulev, S. K. et al. Changing state of the climate system. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 287–422, 2021).

Song, X. et al. DC_OCEAN: An open-source algorithm for identification of duplicates in ocean database. Frontier in Marine Science 6 (2024).

Fofonoff, N. P., Hayes, S. & Millard, R. C. WHOI/Brown CTD microprofiler: methods of calibration and data handling. (1974).

Gregg, M. C. & Hess, W. C. Dynamic response calibration of Sea-Bird temperature and conductivity probes. J Atmos Ocean Tech 2, 304–313 (1985).

Johnson, G. C., Toole, J. M. & Larson, N. G. Sensor corrections for sea-bird SBE-41CP and SBE-41 CTDs. J Atmos Ocean Tech 24, 1117–1130 (2007).

Watkins, M. M. et al. Improved methods for observing Earth’s time variable mass distribution with GRACE using spherical cap mascons. J. Geophys. Res.- Solid Earth 120, 2648–2671 (2015).

Lu, Y. et al. North Atlantic–Pacific salinity contrast enhanced by wind and ocean warming. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 723–731 (2024).

Barnoud, A. et al. Revisiting the global mean ocean mass budget over 2005‐2020. Ocean Science 19, 321–334 (2023).

Mu, D. et al. Contrasting discrepancy in the sea level budget between the North and South Atlantic Ocean since 2016. Earth and Space Science 11, e2023EA003133 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank NOAA/NCEI scientists for long-term data preservation and maintaining the WOD and WOA. This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 42261134536), the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFF0806500), the International Partnership Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. 060GJHZ2024064MI), Asia Cooperation Fund, the new Cornerstone Science Foundation through the XPLORER PRIZE, National Key Scientific and Technological Infrastructure project “Earth System Science Numerical Simulator Facility” (EarthLab), the Young Talent Support Project of Guangzhou Association for Science and Technology, the Youth Independent Innovation Science Foundation (Grant No. ZK24-54), and the China Scholarship Council (Grant no. 202204910270). This work was also supported by the Oceanographic Data Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The calculations in this study were carried out on the ORISE Supercomputer. The Argo Program is part of the Global Ocean Observing System.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.C., Z.T. and V.G. designed the research and methods. Z.T. wrote the first manuscript and created the figures. Z.T., Y.Z., Y.P., H.Y., V.G. and B.Z. prepared the data. Y.Z. contributed to the data formatting. Z.T., V.G., L.C., Y.Z., G.L, Z.W. and B.Z. analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the writing and reviewing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, Z., Zhu, Y., Cheng, L. et al. CODC-S: A quality-controlled global ocean salinity profiles dataset. Sci Data 12, 917 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05172-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05172-9

This article is cited by

-

Ocean Heat Content Sets Another Record in 2025

Advances in Atmospheric Sciences (2026)