Abstract

Paleo-changes in upper range limit of trees provide a valuable analogue for understanding how high-elevational-trees may respond to future climate. Here, we presented a high-resolution (1 km) reconstruction of paleo-changes in the upper range limits of trees across the Tibetan Plateau, at 100-year intervals since the Last Glacial Maximum (~22 kyr BP). This reconstruction was developed by integrating multi-satellite-derived high-resolution map, in situ dendrochronological observation and paleoclimate dataset into a novel climate-driven predictive model. The model accounts for climate change effects, such as growing season temperatures and local climatic stressors, as well as migration time-lags. Validation demonstrated that the reconstructed paleo-shifts in the upper range limit of trees show strong consistency with dendrochronological reconstructions at the century timescale, corresponding with fossil pollen records from lake sediments during the Holocene period, and supported by phylogeographic evidence. This spatial-temporal explicit database enables the estimation of how paleo-changes in the upper range limit of trees have influenced regional biodiversity, offering critical insights into future changes in high-elevational-trees and their broader regional impacts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Land cover change has been recognized as a principal driver of contemporary biodiversity loss1,2,3. However, climate-driven land cover change in high mountain ecosystems, particularly elevational shifts in the upper range limit of trees, have been largely overlooked in existing biodiversity conservation frameworks. The upper range limit of trees, defines the lower boundary of alpine flora habitat4,5,6. Paleo changes in these limits have reshaped alpine species’ habitats and influenced regional alpine biodiversity patterns by affecting habitat stability, connectivity, and fragmentation5,6. Understanding these paleo dynamics during glacial-interglacial cycles, which are equivalent to future warming scenarios, provides valuable insights into how high-elevation trees might respond to future warming7. However, such studies require spatio-temporal explicit mapping of paleo changes in the upper range limit of trees during glacial-interglacial cycles.

The high elevation mountain ranges of the Tibetan Plateau represent critical global biodiversity hotspots, hosting exceptional assemblages of alpine flora8,9,10. Moreover, the extensive elevation gradients and low human impact on paleoenvironmental records, provides an ideal natural laboratory for investigating paleo changes in upper range limit of trees and their cascading effects on regional alpine biodiversity11. Previous studies have primarily relied on fossil data such as pollen, macrofossils, charcoal, and phylogeographic evidence to reconstruct paleo changes in the upper range limit of trees12,13,14. While these datasets provide important local evidence, these records are spatially and temporally discrete, which still lack sufficient spatio-temporal representativeness. For instance, studies of Naleng Lake in the southern Tibetan Plateau, using ancient DNA (10–8 kyr BP) and fossil pollen records (10.7–8.1 kyr BP), suggest that temperature-driven treelines were 400–600 m higher than present during the Holocene Climate Maximum13,14. Additionally, genetic markers from 590 individuals across 102 populations, derived from chloroplast DNA analysis of Juniperus tibetica in cryptic forest refugia in the southeastern Tibetan Plateau, suggest that the paleo-upper range limit may have reached 3500 m during the Last Glacial Maximum12 (~20 kyr BP). Noted that dendrochronological reconstructions revealed substantial spatial heterogeneity in upslope of trees over past 100 years, with mean upslope migration rates of 1.8 m per decades, and the fastest rates of 8.0 m15,16. This large spatial variation in contemporary changes of upper trees, along with limited paleo observations, raises questions about the regional representativeness of these localized records across the plateau.

In this study, we built a novel climate-driven predictive model from modern satellite derived high-resolution map of upper range limit of trees, and in situ dendrochronological observation, which considered both climate drivers and migration time lags due to seed dispersal and tree establishment17,18,19. The model was used to reconstruct paleo changes in the upper range limit of trees at high-resolution (1 km) with 100-year intervals since the Last Glacial Maximum (~22 kyr BP) using best available paleo climate datasets20. Validations were performed using independent fossil records, dendrochronological reconstructions and phylogeographic evidence. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to generate high spatio-temporal map of paleo changes in upper range limit of trees.

Methods

The climate driven predictive model used to reconstruct paleo changes in upper range limit of trees consists of two main components: (1) climate impacts, which are determined based on contemporary relationships between spatial patterns of the upper range limit of trees and modern climate such as growing season temperature and spring drought; (2) migration time lags, which account for seed dispersal and tree establishment processes inferred from in situ dendrochronological observations. To achieve this, we first created a high-resolution map of the current upper range limit of trees using multi-source remote sensing data (Step 1 in Fig. 1). We then identified thermal treeline positions (Step 2.1), which are determined by an isotherm of the mean growing-season temperature6,21,22. However, trees do not always reach their thermal treeline, and they are often confined to lower elevations due to local stresses4,23,24. To account for those local stresses, we calculated the elevational difference between the satellite-derived upper range limit of trees and the thermal treeline, denoted as DTreeline5,6. Using a random-forest algorithm, we established contemporary relationships between DTreeline and current climate variables (Step 2.2). Finally, the elevation of the upper range limit of trees was calculated as the thermal treeline minus DTreeline. Moreover, the climate impacts built using a space-for-time substitution, ignored migration time lags due to seed dispersal and tree establishment processes. We inferred those time lags based on in situ dendrochronological observations that potentially limited only by temperature (Step 3). The climate driven predictive model included both climate impacts (Step 2) and migration time lags (Step 3) were used to reconstruct paleo changes in upper range limit of trees (Step 4).

Mapping current upper range limit of trees based on multi-source remote sensing data

The upper range limit of trees is defined as the uppermost boundary where tree cover exceeds 10%. Publicly-available datasets systematically underestimate forest extent in mountainous regions and areas with sparse tree cover25,26, consequently leading to an underestimation of the upper range limit of trees. These limitations stem from insufficient local ground insights and methods that inadequately capture forest characteristics in challenging terrain. To overcome these limitations, we developed an integrated approach that combines multiple remote sensing data sources within a convolutional neural network (CNN) model framework27 (Step 1.1 in Fig. 1). Specifically, the model integrates vegetation structural information from GEDI LiDAR28, texture features from Sentinel-1A microwave data29, and spectral characteristics from Landsat imagery30. Note that we enhanced our analysis in mountainous regions using terrain-corrected GEDI vegetation height data. This correction, which based 3D LiDAR radiative transfer modeling31, significantly improved our ability to differentiate between grass, shrub, and forest vegetation types across complex topography. Ablation studies demonstrate that models incorporating multi-source data consistently outperform those relying on single-source datasets, with accuracy improvements of 7%–23% across validation regions (Table 1). This highlight the proposed multi-channel CNN framework could effectively leveraged complementary information from diverse vegetation structure, texture features, and spectral bands to capture complex distribution of trees that would be missed by any individual data source alone32,33.

The abovementioned forest extent map was then utilized as input for forest edge detection via the Canny algorithm6, which identified forest boundaries by detecting abrupt changes in the forest extent map (Step 1.2 in Fig. 1). We removed the lower forest boundary and retained only the upper forest edges by defining a local adaptive elevation threshold, below which pixels were excluded6. Specifically, we constructed a histogram of forest edge elevations within a defined window size centered on each geographic point. The selection of the window size was determined through empirical analysis (ranging from 0.1°–1°), aiming to balance the inclusion of both the upper and lower edges. We then evaluated the unimodality of the distribution within each window by smoothing the histogram using a Savitzky-Golay filter. This processing aims to estimate the number of Gaussian components in the forest edge elevation. For example, if multiple Gaussian components were detected, we identified a threshold to separate the upper and lower distributions, based on the position that captures 99.6% of the signal in a Gaussian distribution. Subsequently, the lower forest edges were eliminated and iterated this process until a unimodal distribution was achieved (i.e., the presence of a single Gaussian component). Thus, we obtained the multi-satellite-derived upper range limits of trees across the Tibetan Plateau.

Simulating climate effects based on modern satellite-based observations

To consider both global thermal constraints and local stressors, we first determined the thermal treeline positions, representing the cold edge of the fundamental niche of trees4,23 (Step 2.1 in Fig. 1). The thermal treeline corresponds to isotherm of 6.4 ± 0.7 °C for mean growing-season air temperature at 2 m above the ground (Tair) from WorldClim dataset22, and 7.6 ± 1.0 °C for the mean growing-season land surface temperature (Tsurface) from Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer6 (MODIS). Additionally, the growing season length must exceed 94 days, with the start and end of the growing season defined as the dates when the weekly mean air temperature first crosses 0.9 °C for Tair and 0.7 °C for Tsurface, respectively6,22.

Trees often do not reach their thermal treeline, and confined to lower elevations due to local stresses (Step 2.2 in Fig. 1). To quantify this discrepancy, we calculated the elevational difference between the satellite-derived upper range limit of trees and the thermal treeline, denoted as DTreeline. The regional distribution of DTreeline were determined by local climate stresses, disturbance, soil properties, and topography. After compiling 19 potential predictor variables (Listed in Table 2), we built a full model using random forest to rank their importance and assess their partial contributions to DTreeline, with a detailed description about the sources and meanings of each variable is provided in the Table 2. To enhance model robustness across our extensive temporal scale, we developed a parsimonious model incorporating only six key environmental variables. This approach was adopted because adding more predictors would not significantly improve model accuracy but would increase the risk of extrapolation error when projecting into past climatic conditions. The final set of predictor variables was determined through recursive feature elimination, which systematically identified the most influential factors controlling the upper range limit of trees while minimizing collinearity. The optimal model incorporated spring climatic water deficit (CWD), spring vapor pressure deficit (VPD), cloud cover, minimum temperature of the coldest month, summer dehydration, and surface curvature. Independent validation confirmed the high performance (R2 = 0.84, P < 0.01) of this parsimonious model, while reducing extrapolation error risk. Finally, we calculated the elevation of the upper range limit of trees by subtracting DTreeline from the thermal treeline position.

Simulating the migration time lags based on in situ dendrochronological observations

Due to the inherent delays in seed dispersal and tree establishment, shifts in the upper range limit of trees typically lag behind climate change17,18,19. To quantify this temporal lag, we compiled in situ observations of changes in tree upper range limits using dendrochronological methods (Step 3 in Fig. 1). Specifically, tree-ring samples were collected from 20 strategically selected sites15,34,35,36,37,38 spanning diverse topographic and climatic gradients. At each site, tree-ring samples were collected, carefully extracting cores to preserve the full growth history. The samples were then processed to measure annual growth rings, which were cross-dated to establish a precise chronology of tree growth patterns. By analyzing the tree-ring data, the age of each tree and its growth history were determined. Trees located near the current upper range limits were of particular interest, as their ages provided insights into when they established themselves in these marginal environments. For instance, a tree growing at the edge of the upper range limits that was found to be 50 years old indicates that it colonized this area around 50 years ago. However, only trees that reached a height of 2 m were considered as part of the upper range limits, ensuring that our reconstruction reflects the dynamics of established tree populations rather than small-stature plants, such as transient seedlings or shrubs4. We selected 2 m specifically because this threshold aligns with standard definitions used in satellite products39 and ecology studies4,15. This criterion allows us to accurately track the advancement of upper trees over time. We specifically focused on sites within the thermal treeline threshold (N = 8), which are predominantly temperature-controlled, to isolate and measure the temporal response to climate warming. We systematically tested time lags ranging from 10 to 100 years to optimize our climate-driven predictive model. By minimizing the discrepancy between simulated and observed shifts in the upper range limit over the past century, we determined that incorporating a 50-year time lag maximizes the model’s explanatory power in representing the historical dynamics in upper range limit of trees.

Reconstruction of paleo changes in the upper range limit of trees

We integrated paleoclimatic, contemporary, and projected climate data spanning 22 kyr BP through the end of the 21st century from multiple sources (Step 4 in Fig. 1). Historical climate reconstructions were derived from CHELSA-TraCE21k20 (Climatologies at High resolution for the Earth’s Land Surface Areas), which provides centennial-scale temporal resolution (100-year intervals) and fine spatial resolution (1 km) extending back to 22 kyr BP. Present-day climatological conditions (2020 CE) were extracted from the WorldClim database40. For future climate projections, we analyzed ensemble outputs from nine Earth system models participating in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6), examining late-century conditions (2080–2099 means) under three distinct emissions pathways: the low-emission SSP1–2.6, moderate-emission SSP2–4.5, and high-emission SSP5–8.5 scenarios. These Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) represent integrated frameworks that combine societal development trajectories with specific radiative forcing levels (measured in W m−2) anticipated to peak before 2100.

We then use the abovementioned predictive model that consider both climate effect and migration time lags to reconstruct spatial-temporal changes in the upper range limit of trees at a temporal resolution of 100 years from the LGM to the end of this century (2080–2099) under the three emissions scenarios at the spatial resolution of 1 km. Our detailed reconstruction reveals substantial fluctuations in the upper treeline elevation across the Tibetan Plateau during the past 22 kyr, with elevation change exceeding 850 m, approximately one-fifth of its present elevation (4009 ± 383 m). It reached its lowest elevation during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, 22–19 kyr BP), peaked during the Holocene Climate Optimum (HCO, ~10–6.5 kyr BP), and then gradually decreased to present levels. By the end of the century, projections suggest a return to HCO-comparable elevations (SSP2–4.5 scenario), or even higher elevations (~240 m above present) under the SSP5–8.5 scenario. Moreover, significant regional heterogeneity emerges between southern (red line in Fig. 2) and northern (blue line in Fig. 2) Tibetan Plateau. The southern region exhibits a more pronounced and rapid response to climate change compared to the northern one. For example, during the deglaciation (~18–14 kyr BP) and the HCO (~10–6.5 kyr BP), the upper range limit of trees in southern regions revealed a steeper upward trajectory, indicating faster upslope migration rates. Similarly, the decline during the late Holocene was also more pronounced in the southern regions, suggesting greater sensitivity to temperature change. Spring drought and frost appears to disproportionately constrain the dynamics in the more arid northern regions. The divergence in the timing and rate of changes in upper range limit of trees between the southern and northern Tibetan Plateau has become more pronounced in recent centuries, with the southern regions continuing to rise rapidly, while the northern one experiences a slower, more modest increase, leading to a growing regional disparity in the current climate optimum.

Paleo changes in upper range limit of trees at a 100-year interval across the Tibetan Plateau over the past 22 kyr BP. The elevation changes of the upper range limit of trees on the Tibetan Plateau were reconstructed used the CHELSA TraCE-21k paleoclimate dataset (left), and projection to the end of this century (right) using CMIP6 multi-model ensemble mean under the SSP1–2.6 (yellow), SSP2–4.5 (blue) and SSP5–8.5 (red) scenario, respectively. The gradient yellow and blue solid lines represent the changes in the upper range limit of trees elevation in the southern (<35°N) and northern (>35°N) parts of the Tibetan Plateau, respectively. Spatial distribution of the upper range limit of trees at 1 km2 resolution in each period were displayed above the graph, which red indicates higher elevation while yellow marks low elevation. The black box on the right represents satellite-based observation. The whiskers and boxes represent the 5th, 25th, 75th, and 95th percentiles and the black lines show mean values.

Data Records

The paleo-upper range limit of trees dataset41 is archived on Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28602974.v2). This dataset available in CSV format, can be visualized spatially using GIS software such as ArcGIS. Each row represents a specific location with its corresponding upper range limit of trees, while columns represent temporal intervals at 100-year resolution for past 22 ka. Grid cells marked as NaN indicate areas with no trees.

Technical Validation

Validation of the contemporary satellite-based upper range limit of trees

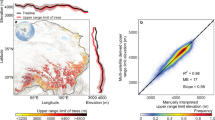

We demonstrate the efficacy of our integrated approach that synthesizes multiple remote sensing datasets within a convolutional neural network (CNN) framework. Our validation employed 602,879 reference points interpreted from high-resolution (<5 m) satellite imagery accessed through Google Earth. The validation dataset was systematically constructed using a 0.01° mesh grid spanning the Tibetan Plateau, with approximately ten 30-m resolution samples randomly selected per grid cell. Six trained analysts conducted visual interpretation of these samples, with results undergoing cross-validation and subsequent quality control review to ensure consistency across the dataset. In these high-resolution images, trees exhibit distinctive visual signatures that facilitate accurate identification. Specifically, trees manifest as textured objects casting characteristic shadows, with discernible crown structures and spatial patterns that distinguish them from other land cover types. Shrubs typically display lower stature and more uniform texture, while grasslands present homogeneous surfaces without pronounced vertical elements. Rocky surfaces and bare ground are identifiable by their distinctive spectral properties and absence of vegetation shadows. These visual discriminants enabled our trained analysts to reliably differentiate tree cover from other landscape features. This rigorous process yielded a comprehensive validation dataset with balanced spatial distribution across the Tibetan Plateau: 30,746 samples (5.1%) in the northern region, 510,035 (84.6%) in the southern region, and 62,098 (10.3%) in the inner region. Statistical analysis revealed high agreement between our satellite-derived upper range limit of trees and manual interpretations from high-resolution imagery in northern (R² = 0.97, Slope = 0.98, Mean Error = 5 m), southern (R² = 0.97, Slope = 0.97, Mean Error = 4 m) and inner regions (R² = 0.94, Slope = 0.94, Mean Error = 4 m), confirming the robustness of our methodology (Fig. 3). Noted that we also generated high accuracy map in relative sparce distributed tree region (R2 = 0.96) out performing open available tree cover datasets (R2 = 0.22).

Validation of the multi-satellite-derived upper range limit of trees over the Tibetan Plateau. (a) Spatial distribution of the upper range limit of trees at 1 km2 resolution in the northern, southern and inner Tibetan Plateau, respectively. (b–d) The relationships between the multi-satellite-derived upper range limit of trees and visual interpretation from Google Earth images, with the 1:1 line (dashed) and the regression line (continuous) in the (b) northern, (c) southern and (d) inner Tibetan Plateau, respectively. R2 and ME indicate the coefficient of determination and the mean error, respectively.

Validation of historical shifts in upper range limit of trees over the past century

We collected reconstruction of past shifts in the upper range limit of trees based on dendrochronological methods across the Tibetan Plateau (see details in simulating the migration time lags, Table 3). We then classify these sites into two groups based on their thermal regimes: 8 sites fall within thermal treeline threshold were used to quantify temporal lags in response to climate warming, while the remaining 12 sites served as an independent validation dataset. Our reconstructed changes in upper range limit of trees are consistent with dendrochronological reconstruction (R² = 0.68, P < 0.01), estimated an upslope migration rate of 2.0 ± 2.1 m decade−¹ (Fig. 4b). This closely matches the rate of 1.8 ± 2.3 m decade−¹ determined through direct dendrochronological dating of tree establishment at different elevations. This demonstrates the robustness of our model for reconstruction changes in the upper range limit of trees on century timescales.

Validation of the model-based reconstruction of upper range limit of trees using dendrochronological reconstruction at the century scale and fossil pollen abundance records from lake sediments during the Holocene period. (a) Spatial distribution of the dendrochronological-reconstructed shifts in upper range limit of trees over the past century and six lakes containing Holocene fossil pollen records. The background terrain obtained from ArcGIS basemap dataset. (b) the model-data comparison at sites with and without trees reaching the thermal treeline. (c) The comparison between pollen-based reconstruction of upper range limit of trees at each lake site during the Holocene. The green shading represents pollen-derived arboreal pollen percentage (see Methods).

Validation of paleo changes in the upper range limit of trees during the Holocene

To verify the reliability of the paleo changes in upper range limit of tree, we compiled a fossil pollen dataset derived from lake sediments across the Tibetan Plateau11 (Fig. 4a). Specifically, we selected fossil pollen records that fall within a 500 km radius of the present-day forest communities and encompass the entire Holocene period with a temporal resolution of at least 500 years. This selection process yielded a total of six fossil pollen records situated below, at and above the current upper range limit of trees elevations13,42,43,44,45,46. Noted that Juniperus constitute important treeline species, however, their pollen cannot be reliably identified in fossil records using current techniques, thus limiting their inclusion in our model validation. We then concentrated on the four most common high-elevational arboreal tree taxa—Betula, Abies, Picea, and Pinus in each fossil pollen record. The pollen abundance thresholds were then used to determine whether any of the tree taxa were present in the fossil pollen site throughout the Holocene11. To enable a comparison between pollen-derived data and our model reconstruction, the same grid cells covered by the pollen-derived data were selected from our high-spatial-resolution reconstructed dataset. The pollen records revealed during the early to middle Holocene (~10–4 kyr BP) upper range limit of trees over Tibetan Plateau were consistent higher than 3780 m, but were lower than 4540 m, since trees persisted at lower elevations, such as Lake Wuxu (3710 m) and Muge Co (3780 m), while they were absent from higher-elevation sites, including Koucha Lake (4540 m) and Saiyong Co Lake (4545 m). Moreover, trees migrated to higher elevations between 11 and 3 kyr BP at Naleng Co (4200 m) and Yidun Lake (4470 m), before descending to their current elevations around ~3 kyr BP. Those timing and elevational shifts were closely match our model reconstruction.

Moreover, we also compare with phylogeographic evidence from the Picea crassifolia47 and Juniperus przewalskii studies12. In southeastern Tibetan Plateau, our reconstructed upper range limit of trees could distributed at 3390 ± 316 m, with highest elevation (95 percentile) reaching 3911 m during LGM (~22–20 kyr BP). The long existence of trees is consistent with phylogeographic evidence presented by Opgenoorth et al.12 on Juniperus przewalskii, and supported the hypothesis of “microrefugia existence” throughout the present distribution range in the southeastern Tibetan Plateau potentially including highest treeline during LGM above 3900 m. In the northern Tibetan Plateau, our reconstruction revealed trees were restricted to the very edges of the Tibetan Plateau during the LGM (~22–20 kyr BP), with no presence across the plateau interior. As with warming climate, trees expanded inward from these edge refugia, reaching their maximum distribution during the mid-Holocene (~8–6 kyr BP). This finding aligns well with the phylogeographic evidence presented by Meng et al.47 on Picea crassifolia, supporting the “expansion” hypothesis that northern Tibetan Plateau platform populations are derived from a widely distributed refugial population that existed along the northern edge of the Plateau.

Usage Notes

The Methods and Data Records sections offer a detailed framework for reconstructing paleo changes in upper range limit of trees, enabling researchers to apply the dataset effectively in their own studies. This resource supports investigations into how past shifts in upper range limit of trees over the Tibetan Plateau since the LGM, have influenced species diversity, and ecosystems functioning. For instance, the dataset has already been used to analyze habitat changes for alpine endemic species, distributed above upper trees, revealing that alpine habitats contracted to a minimum of 503,035 km² during the mid-Holocene (75% of present-day area) and expanded to 849,574 km² at the LGM (150% of the current 597,788 km²). These fluctuations underscore how upper range limit of trees dynamics have profoundly shaped beta-diversity patterns in alpine regions, emphasizing the need to integrate paleoclimate and historical treeline data when interpreting modern biodiversity gradients5. Our spatially explicit time-series reconstruction could also provide detailed mapping of existence of “cryptic forest microrefugia” in the heterogeneous topographies of high-mountain region in southeastern Tibetan Plateau12, and supported the “expansion” hypothesis that northern Tibetan Plateau populations are derived from a widely distributed refugial population that existed along the northern edge of the Plateau47.

The reconstruction method developed here is broadly applicable to mountain ecosystems worldwide, offering valuable insights for alpine vegetation research. Nonetheless, paleo-reconstructions are subject to several uncertainties. Our approach employs a parsimonious model that emphasizes climatic drivers and excludes natural and anthropogenic disturbances, as these factors have limited influence at the scale of the entire Tibetan Plateau. However, at local scales, disturbances such as fire and grazing can significantly affect shifts in the upper range limit of trees. Moreover, the accuracy of our reconstructions depends crucially on the reliability of paleoclimate data. For example, Holocene temperature trends remain contentious, with proxies indicating cooling while models suggest warming. Resolving these discrepancies will require more extensive fossil records and a broader array of paleoclimate evidence to refine treeline reconstructions. Additional paleoecological data such as sedimentary ancient DNA are also essential for identifying refugia and assessing vegetation–climate lag times.

Data availability

The Landsat multi-spectral images, Sentinel-1A microwave data, and GEDI-derived canopy height can be accessed at https://developers.google.cn/earth-engine/datasets. The climatological land surface temperature from the MODIS MOD11A1 product can be accessed at https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/. The current climate dataset from WorldClim and TerraClimate are freely available at https://worldclim.org/ and https://www.climatologylab.org/terraclimate.html, respectively. The monthly paleo-climate dataset from CHELSA-TraCE21k and projected future climate data from the CMIP6 can be download at https://chelsa-climate.org/ and https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/, respectively. The elevation data from SRTM can be accessed at https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/instruments/srtm.

Code availability

The climate-driven predictive random forest model48 used in this study has been deposited in the Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28348190.v2). All additional code utilized in this study for remote sensing data analysis is available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Jung, M. et al. A global map of terrestrial habitat types. Sci. Data 7, 256 (2020).

Jung, M. et al. Areas of global importance for conserving terrestrial biodiversity, carbon and water. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 1499–1509 (2021).

Newbold, T. et al. Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. Nature 520, 45–50 (2015).

Körner, C. The cold range limit of trees. Trends Ecol. Evol. 36, 979–989 (2021).

Xu, J. et al. Late Quaternary fluctuation in upper range limit of trees shapes endemic flora diversity on the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Commun. 16, 1819 (2025).

Wang, X. et al. Enhanced habitat loss of the Himalayan endemic flora driven by warming-forced upslope tree expansion. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 890–899 (2022).

Tierney, J. E. et al. Past climates inform our future. Science 370, eaay3701 (2020).

Ding, W., Ree, R. H., Spicer, R. A. & Xing, Y. Ancient orogenic and monsoon-driven assembly of the world’s richest temperate alpine flora. Science 369, 578–581 (2020).

Antonelli, A. et al. Geological and climatic influences on mountain biodiversity. Nat. Geosci. 11, 718–725 (2018).

Li, X., Zhu, X., Niu, Y. & Sun, H. Phylogenetic clustering and overdispersion for alpine plants along elevational gradient in the Hengduan Mountains region, southwest China. J. Syst. Evol. 52, 280–288 (2014).

Cao, X., Herzschuh, U., Ni, J., Zhao, Y. & Böhmer, T. Spatial and temporal distributions of major tree taxa in eastern continental Asia during the last 22,000 years. The Holocene 25, 79–91 (2015).

Opgenoorth, L. et al. Tree endurance on the Tibetan Plateau marks the world’s highest known tree line of the Last Glacial Maximum. New Phytol. 185, 332–342 (2010).

Kramer, A., Herzschuh, U., Mischke, S. & Zhang, C. Holocene treeline shifts and monsoon variability in the Hengduan Mountains (southeastern Tibetan Plateau), implications from palynological investigations. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 286, 23–41 (2010).

Liu, S. et al. Sedimentary ancient DNA reveals a threat of warming-induced alpine habitat loss to Tibetan Plateau plant diversity. Nat. Commun. 12, 2995 (2021).

Liang, E. et al. Species interactions slow warming-induced upward shifts of treelines on the Tibetan Plateau. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 4380–4385 (2016).

Lu, X., Liang, E., Wang, Y., Babst, F. & Camarero, J. J. Mountain treelines climb slowly despite rapid climate warming. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 30, 305–315 (2021).

Alexander, J. M. et al. Lags in the response of mountain plant communities to climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 563–579 (2018).

Zheng, X. et al. Density‐dependent species interactions modulate alpine treeline shifts. Ecol. Lett. 27, e14403 (2024).

Sigdel, S. R. et al. Accelerated succession in Himalayan alpine treelines under climatic warming. Nat. Plants 10, 1909–1918 (2024).

Karger, D. N., Nobis, M. P., Normand, S., Graham, C. H. & Zimmermann, N. E. CHELSA-TraCE21k – high-resolution (1 km) downscaled transient temperature and precipitation data since the Last Glacial Maximum. Clim. Past 19, 439–456 (2023).

Körner, C. & Paulsen, J. A world‐wide study of high altitude treeline temperatures. J. Biogeogr. 31, 713–732 (2004).

Paulsen, J. & Körner, C. A climate-based model to predict potential treeline position around the globe. Alp. Bot. 124, 1–12 (2014).

Körner, C. & Hoch, G. Not every high‐latitude or high‐elevation forest edge is a treeline. J. Biogeogr. 50, 838–845 (2023).

Müller, M. et al. How do soil properties affect alpine treelines? General principles in a global perspective and novel findings from Rolwaling Himal, Nepal. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 40, 135–160 (2016).

Bastin, J. et al. The extent of forest in dryland biomes. Science 356, 635–638 (2017).

Liu, L. et al. Finer-resolution mapping of global land cover: Recent developments, consistency analysis, and prospects. J. Remote Sens. 2021, 2021/5289697 (2021).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 60, 84–90 (2017).

Dubayah, R. et al. The global ecosystem dynamics investigation: high-resolution laser ranging of the Earth’s forests and topography. Sci. Remote Sens. 1, 100002 (2020).

Torres, R. et al. GMES Sentinel-1 mission. Remote Sens. Environ. 120, 9–24 (2012).

Wulder, M. A. et al. Current status of Landsat program, science, and applications. Remote Sens. Environ. 225, 127–147 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Forest canopy height extraction in rugged areas with ICESat/GLAS data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 52, 4650–4657 (2014).

Wang, B. et al. Bamboo classification based on GEDI, time-series Sentinel-2 images and whale-optimized, dual-channel DenseNet: A case study in Zhejiang province, China. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 209, 312–323 (2024).

Dwiputra, A., Coops, N. C. & Schwartz, N. B. GEDI waveform metrics in vegetation mapping—a case study from a heterogeneous tropical forest landscape. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 015007 (2023).

Liang, E., Wang, Y., Eckstein, D. & Luo, T. Little change in the fir tree‐line position on the southeastern Tibetan Plateau after 200 years of warming. New Phytol. 190, 760–769 (2011).

Wang, Y., Zhu, H., Liang, E. & Camarero, J. J. Impact of plot shape and size on the evaluation of treeline dynamics in the Tibetan Plateau. Trees 30, 1045–1056 (2016).

Ran, F., Liang, Y., Yang, Y., Yang, Y. & Wang, G. Spatial–temporal dynamics of an Abies fabri population near the alpine treeline in the Yajiageng area of Gongga Mountain, China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 34, (2014).

Lyu, L., Zhang, Q., Deng, X. & Mäkinen, H. Fine-scale distribution of treeline trees and the nurse plant facilitation on the eastern Tibetan Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 66, 251–258 (2016).

Cui, J., Qin, J. & Sun, H. Population spatial dynamics of Larix potaninii in alpine treeline ecotone in the eastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau, China. Forests 8, 356 (2017).

Hansen, M. C. et al. High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science 342, 850–853 (2013).

Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. WorldClim 2: new 1‐km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302–4315 (2017).

Xu, J. et al. Paleo-upper range limit of tree elevation from the last glacial maximum (LGM) to 1950 common era (CE). figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.28602974.V2 (2025).

Shen, C., Liu, K., Tang, L. & Overpeck, J. T. Quantitative relationships between modern pollen rain and climate in the Tibetan Plateau. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 140, 61–77 (2006).

Liu, L. et al. Vegetation and environmental changes since the last glacial maximum inferred from a lake core from Saiyong Co, central Tibetan Plateau. The Holocene 32, 543–553 (2022).

Herzschuh, U., Kramer, A., Mischke, S. & Zhang, C. Quantitative climate and vegetation trends since the late glacial on the northeastern Tibetan Plateau deduced from Koucha Lake pollen spectra. Quat. Res. 71, 162–171 (2009).

Sun, W., Zhang, E., Jones, R. T., Liu, E. & Shen, J. Asian summer monsoon variability during the Late Glacial and Holocene inferred from the stable carbon isotope record of black carbon in the sediments of Muge Co, southeastern Tibetan Plateau, China. The Holocene 25, 1857–1868 (2015).

Zhang, E., Wang, Y., Sun, W. & Shen, J. Holocene Asian monsoon evolution revealed by a pollen record from an alpine lake on the southeastern margin of the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau, China. Clim. Past 12, 415–427 (2016).

Meng, L. et al. Mitochondrial and chloroplast phylogeography of Picea crassifolia kom. (Pinaceae) in the Qinghai‐Tibetan Plateau and adjacent highlands. Mol. Ecol. 16, 4128–4137 (2007).

Xu, J. Source code for: Climate-driven predictive model. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.28348190.V2 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Project of China (No. 2023YFF0805202), the Excellent Research Group Program for Tibetan Plateau Earth System (No. 42588201), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42371118).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.W. and T.W. designed the study. J.X. and X.W. performed analysis and prepared figures. X.W. and J.X. wrote the manuscript. X.C., E.L., L.Z., X.S. and T.W. contributed to the interpretation of the results and to the text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, J., Wang, X., Cao, X. et al. Spatio-temporally explicit reconstruction of upper range limit of trees since the LGM over the Tibetan Plateau. Sci Data 12, 868 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05236-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05236-w