Abstract

Agriculture remains a backbone of the African economy, contributing up to 70% of household income in rural areas. Yet crop yields across Africa are rising at a slower rate than the global average. Currently, strategies to improve agricultural productivity are limited by the availability of granular, accurate, and spatially-extensive data. These disaggregated statistics are required to understand how crop yields respond to climate variability, climate extremes, and agronomic practices. Here, we present GROW-Africa, a database that includes n = 535,844 georeferenced observations of crop yields across Africa focusing on 25 key crops including maize, sorghum, cassava, groundnuts, cowpeas, rice, yams, and millet. The database assimilates observations from a range of spatial scales, from regional government statistics, to household farmer surveys, to plot-level crop cuts. We use co-located observations to identify sources of bias and error in these varied data types. Finally, we demonstrate how the GROW-Africa database can be used to train remote sensing algorithms to produce continuous maps of crop yields across Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Improving the productivity of smallholder farmers is a cornerstone of economic development and food security in Africa1. For example, a 1% rise in agricultural GDP results in an estimated 6% rise in income growth for the poorest decile of the income distribution2,3. Yet yield improvements in Africa have been sluggish over the last decades. Fig. 1a,b shows global patterns of crop yields (production divided by harvested area) for maize and rice over the last 30 years. Current crop yields in Africa are not only ~2× lower than the global average, but also are increasing at a rate that is ~2× times slower than the global average (Fig. 1a,b). In other words, the yield disparities are expanding— not shrinking— over time.

Improving crop yields is core to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal Targets 2.3 and 2.4, which focus on: (i) doubling agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers, and (ii) implementing sustainable and resilient agricultural practices that strengthen capacity for adaptation to climate change. High-quality agricultural data are essential for addressing these challenges. For example, observations of productivity across space and time4,5 allow one to elucidate the climatic6,7,8,9,10,11,12, political13, and agronometric14,15,16 drivers of yield. Such knowledge can be used to make better predictions for how crop yields will respond to climate change.

Unfortunately, agricultural data are the sparsest in countries where yield improvements are most needed17,18 (Fig. 1c). Household farm surveys continue to be the basis for agricultural statistics in Africa2. Yet, at current survey frequencies, a given African household will appear in a household well-being survey less than once every 1000 years, or about 100 times less frequently than a household in the United States19.

The paucity of on-the-ground agricultural data (Fig. 1c) is juxtaposed by the rapidly-expanding opportunities for satellite-based monitoring of agricultural production17,20. For example, as of May 2023, there were 1,040 active nonmilitary Earth Observation satellites in orbit, 67% of which were launched within the previous five years21. This fleet of Earth Observation satellites now provides frequent global coverage of a wide variety of agriculturally-relevant observations, including but not limited to land surface reflectance across a range of wavelengths of light22 and the derived gross primary productivity (GPP), net primary productivity (NPP)23, leaf area index (LAI)24, and fraction of photosynthetically active radiation (fPAR) absorbed by green vegetation24, the solar-induced fluorescence (SIF)25,26,27, the radar-derived soil moisture28, and many others.

Thus, on one hand, Earth Observation satellites present a solution to the scarcity of agricultural data in Africa17; in regions where sufficient ground-truth data exist, algorithms can be trained to transform satellite observations into estimates of crop distribution and crop yields29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. On the other hand, yield estimates derived from remote sensing currently are limited by the extent and quality of ground-truth data needed for algorithmic calibration and validation17,31. Burke et al. (2021)17 succinctly summarized the problem: “The largest constraint to satellite-based model performance is now training data rather than imagery”17.

Here, we respond to this data gap by curating GROW-Africa38 (Groundtruthing Remote-sensing for Optimizing Yield in Africa), a database of more than half a million (n = 535,844) geo-referenced observations of crop yields in Africa. These observations come from a variety of sources and describe a cascade of spatial scales, from country-level observations reported by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)39, to regional statistics generated by national Ministries of Agriculture40, to household data from farmer surveys41,42, to plot-scale variety trials, agronometric surveys, and crop cuts14,16,43. Integrating data from these varied sources requires identifying (and then removing) systematic biases between them. We find that both government statistics and farmer surveys systematically over-estimate crop yields relative to the gold-standard of crop-cuts. We resolve these biases as a function of both crop type and country. Finally, we illustrate a workflow for how the data in GROW-Africa can be used to calibrate remote sensing algorithms that translate freely-available satellite datasets into wall-to-wall estimates of crop yields.

Methods

Curation of a continent-wide agricultural production database

The GROW-Africa database38 compiles yield observations from three broad spatial scales: (1) country-level observations, (2) sub-national (regional) observations, and (3) local (point) observations. We describe each category briefly below. See Table 1 and the Supplementary Information for more details about the data sources.

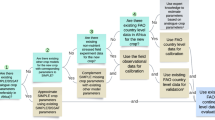

National data

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) collects data acquired by each member country’s national statistics service and maintains a database of annual crop production39. These national-level statistics form the basis for Fig. 1a,b. Note, however, that the national-level statistics are both: (1) highly uncertain due to the large degree of imputation and upsampling required to generate national estimates, and (2) aggregated to such a coarse spatial scale that they provide sparse and relatively weak constraints for training algorithms to quantify agricultural production from satellite data (Fig. 2). These limitations of the national data motivated our compilation of spatially-disaggregated regional and local crop production data. All told, the national-level data represent about 2% of the observations in the GROW-Africa database (Fig. 2).

An overview of the composition of the GROW-Africa database. In total, GROW-Africa38 contains n = 535,844 geo-referenced observations of historical crop yields in Africa, spanning 25 crops: banana, barley, beans, cassava, coffee, cotton, cowpea, fonio, groundnut, maize, millet, okra, pigeon pea, potato, rice, sesame, sorghum, soyabean, sugar cane, sweet potato, taro, teff, tobacco, wheat, and yam. National (country-level) data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)39 represent a small fraction (2.2%) of the database. Most of the database represents sub-national government statistics (34.6%), farmer survey data from the World Bank’s Living Standards Measurement Study (LSMS)41 (36.4%), and other local (farm-scale) data (26.7%), principally from the One Acre Fund16.

Sub-national (province-, district-, and state-level) data

In many countries, national Ministries of Agriculture produce annual reports in which they estimate the harvested area, production, and average yield for each of the key crops grown in the country. These statistics are disaggregated to the administrative level-1 and level-2 boundaries (Figure S4). They typically are based on teams of surveyors that are deployed to perform a random sampling of smallholder farms40. A number of projects have aimed to digitize these sub-national agricultural production statistics, including Agro-MAPS44, the ReSAKSS Country eAtlases45, and HarvestStat Africa, which consists of data compiled by USAID’s Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) and NASA Harvest40,46 (see Supplementary Information, section 1.2). We compile the regional data from these varied sources (Table S2), harmonize the place names and crop names, link each observation to a unique geospatial identifier and associated vector polygon, and then remove duplicate observations. The resulting compilation of sub-national-level data represents approximately 35% of the observations in the GROW-Africa database (Fig. 2).

Local data

In comparison to the national data, the sub-national data offer a meaningful step forward in terms of spatial disaggregation and granularity. However, the sub-national observations still represent regions that span hundreds to millions of individual pixels in a satellite dataset, hampering the ability to calibrate and validate remote sensing algorithms17. To achieve another level of spatial disaggregation, we compile point observations from household farmer surveys and crop cuts (Fig. 2).

The largest source of point observations in GROW-Africa38 is the collection of farmer surveys associated with the World Bank’s Living Standards Measurement Study - Integrated Surveys on Agriculture (LSMS-ISA) project (Table 1). The LSMS-ISA project has coordinated multi-year surveys in 13 countries in sub-Saharan Africa47: Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Malawi, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Tanzania, Togo, and Uganda. Table 1 lists each of the 45 annual LSMS-ISA surveys compiled in our database. The surveys span the interval 2004–2022.

The LSMS-ISA surveys typically include two on-farm visits: one visit post-planting and one visit post-harvest. The post-planting visits are used to survey field areas and to quantify the fraction of each field planted to a given crop (since many fields are inter-cropped). The post-harvest visits are used to quantify production. Thus, the final crop yield statistics have errors arising from the uncertain estimates of: (i) field areas, (ii) inter-cropping fractions, and (iii) total crop production. We explore these various sources of noise and error in Figs. 6–8 below.

A second caveat of the farmer survey data is that, for privacy considerations, most survey datasets have been geospatially anonymized by adding random jitter to the GPS coordinates. The standard protocol followed by the World Bank is to randomly displace urban clusters by a distance of 0–2 km and rural clusters by a distance of 0–5 km, with a randomly-selected 1% of the rural clusters displaced a distance of 0–10 km48,49. The result is that point observations from the survey datasets cannot be accurately georeferenced to high-resolution satellite imagery, which limits the utility of these datasets for calibrating high-resolution satellite-based yield mappers29,50. However, the dozens of point observations made within a single (spatially-jittered) survey cluster may provide a reasonable ground-truth constraint to compare with the associated ~ 5 km × ~ 5 km region. Likewise, aggregating survey data to the sub-national administrative boundaries ameliorates the uncertainties associated with the spatial anonymization, although it comes at the expense of reducing the number of ground-truth data constraints (since dozens or hundreds of data points from farmer surveys are aggregated to produce one ground-truth constraint). We explore some of these data treatment approaches in the Data Usage section.

Finally, we compile an additional n = 143,157 observations from other local (point) data sources, including those scraped from the literature14, from farmer surveys outside of the LSMS-ISA project42, and from agronometric survey data collected by the One Acre Fund16 (Fig. 2; Supplementary Information, section 1.3).

Crops included in GROW-Africa

We focus the GROW-Africa database38 on 25 crops (listed in alphabetical order): banana, barley, beans, cassava, coffee, cotton, cowpea, fonio, groundnut, maize, millet, okra, pigeon pea, potato, rice, sesame, sorghum, soyabean, sugarcane, sweet potato, taro, teff, tobacco, wheat, and yam. These 25 crops are chosen because they represent the vast majority (≥90%) of the total cultivated area and contribution to diet (average kilocalories per capita per day) (Figure S1).

Data cleaning and harmonization

The curation of the GROW-Africa database38 involves three steps: (1) standardization and harmonization of crop names, (2) standardization and harmonization of geospatial data (administrative boundaries for national and regional data, and GPS coordinates for point/local data), and (3) removal of duplicate data and filtering of outliers. For the standardization of geospatial data, we use vector shapefiles of administrative level 0, 1, 2, and 3 (where applicable) boundaries available from https://gadm.org/. We assign each administrative boundary a unique ID code that is used to synthesize and harmonize observations from different datasets.

We take a relatively light-touch approach to outlier filtering so that users of the GROW-Africa database can make their own decisions about the handling of outlier data. We choose not to filter outliers from the national and sub-national data. However, the point observations— especially the farmer surveys— have substantial variance in yield estimates, some of which likely represents errors associated with the field area or production estimates (or misreported units) rather than true plot-to-plot yield variability. For example, misreported units (e.g., mislabeling the areas of farmer fields estimated in hectares as m2 or vice versa) can lead to implausible yield values such as ≥100 Mg/ha. As a simple empirical filter, we use the crop-specific yield distributions from the regional (sub-national) database (Fig. 3) to estimate reasonable bounds for crop-specific yields and to identify outliers in the point data. Specifically, we classify yield observations that are either < 10% of the median value (50th percentile) or >200% the 98th percentile of the regional yield distributions in Fig. 3 as outliers that are removed from the filtered dataset of point observations. The final distributions of national, regional, and point-based yield estimates are provided in Fig. 3.

Distributions of yield values (metric tons per hectare) for the 25 crops in the GROW-Africa database38. The data are color-coded in terms of the data type and level of spatial disaggregation: national-level government data are shown in blue, regional-level government data are shown in green, and local (point) data are shown in brown. Maps of the distribution of national, regional, and local data are shown in Figure S3, Figure S4, and Figure S5 of the Supporting Information, respectively. The total number of observations in the GROW-Africa database is shown in the title of each panel, and the mean (μ) and standard deviation (1σ) of the yield values from the national, regional, and local datasets are listed in each subplot.

Data Records

The local, regional, and national crop yield data compiled in the GROW-Africa database are available on Zenodo38 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14961637). The GROW-Africa database divides the observations broadly into two categories based on whether the yield represents: (1) the average value across a geographic region (a national or sub-national administrative boundary) defined by a geospatial polygon, or (2) a point observation associated with a set of GPS coordinates. Each observation from category (1) is assigned a geographic ID code that links the observation to a supplied vector shapefile dataset. The point observations (category 2) are labeled with both their GPS coordinates (which typically have been jittered by 0–5 km according to privacy protocols48,49), and the geographic ID codes describing the nested set of geographic boundaries— administrative level 0, 1, 2, and 3 (where applicable)— in which that point observation falls. Finally, a geospatial look-up-table describes which administrative level-2 regions are located within each administrative level-1 region, etc. This geospatial organization allows for easy aggregation of the raw data to different spatial scales, and it facilitates comparison between different data sources (e.g., farmer surveys vs. regional government statistics), which we explore below (see Technical Validation).

In total, there are four spreadsheet files containing yield data in the GROW-Africa database38: (i) GROW-Africa_Regional, (ii) GROW-Africa_LSMS_survey, (iii) GROW-Africa_LSMS_cropcut, and (iv) GROW-Africa_Point. The regional spreadsheet compiles the government statistical data that have been aggregated by the FAO39, the Global Agro-Ecological Zones Agro-MAPS project44, the Regional Strategic Analysis and Knowledge Support System Country eAtlases45, the HarvestStat project (which consists of data compiled by USAID’s Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) and NASA Harvest), and the USAID Development Data Library51 (Table 1). The LSMS-survey spreadsheet compiles the household farmer survey data from the LSMS-ISA project (Table 1). The LSMS-cropcut spreadsheet includes the crop cut data conducted in tandem with the household surveys (Ethiopia only) (Table 1). Finally, the spreadsheet labeled “Point” compiles all of the point observations of crop yields that are not associated with the LSMS-ISA project. These datasets include the field survey data from the One Acre Fund52, site-specific data from the USAID Development Data Library53, compilations (meta-analyses) of yield data from the scientific literature14, and data from the Centre for Environmental Economics and Policy for Africa (CEEPA)’s African agricultural survey42. Each of the yield data spreadsheets contains columns representing the geographic location, the crop, the harvest year, and the crop yield (in units of metric tons per hectare).

Technical Validation

The GROW-Africa database38 consists approximately equally of observations from (1) sub-national government statistics, (2) farmer survey data from the LSMS-ISA project, and (3) other local data, including agronometric surveys and crop cuts (Fig. 2). Blending observations from these disparate sources requires an understanding of the systematic biases that may exist between them. We analyze overlapping observations (those that describe the same crop for the same region in the same year) from these varied data sources.

Comparing government-reported and survey-based yield estimates

First, we compare the yield estimates that result from aggregating all of the farmer survey observations within an administrative boundary with the corresponding government-reported regional yield. Examples of these data compilations for three countries are shown in Fig. 4. Data for additional countries are shown in Figure S11 of the Supplementary Information. Note that the correlations between co-located government statistics and farmer survey data often are weak (Fig. 4), an observation that casts into question the quality of either or both of the data sources17. Yet, the compilations in Fig. 4 and in the Supplementary Information show stronger correlations than those identified with previous analyses of equivalent— but more limited— datasets (e.g., see Figure 2 of ref. 17).

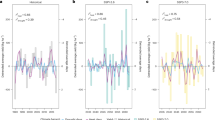

A comparison between government-reported and farmer-reported crop yields for three countries with extensive sub-national and local datasets: (a) Ethiopia, (b) Malawi, and (c) Nigeria. The local (farmer-reported) yield data are aggregated to sub-national (administrative level-1 and level-2) boundaries in order to facilitate comparison with the regional government statistics. The circle size denotes the number of farmer observations that were aggregated to produce the regional estimate. Data points are colored by crop, and the legend shows the correlation coefficient (ρ) between the government-reported and farmer-reported yield estimates. In calculating the correlation coefficients, each data point is weighted by the square root of the number of farmer observations that were averaged together to produce that regional yield estimate. All of the farmer survey data shown here are from the World Bank’s Living Standards Measurement Study (LSMS) (see Table 1). Similar plots for other countries with paired LSMS and government statistics are shown in Figure S11 of the Supporting Information. Note that, in order to fit on the same axes, the yields for cassava, potatoes, sweet potatoes, and yams are scaled by a factor of 20%.

Next, we evaluate whether there is a systematic bias between the co-located government statistics and survey-based yield data. In other words, do official government statistics consistently overestimate or underestimate crop yields relative to farmer surveys? To address this question, we acknowledge that both data sources are imperfect estimates of the true average yield, so we calculate the yield bias in a total least squares sense. Weighing each observation by \(\sqrt{n}\) (where n is the number of farmer observations that were aggregated to generate the regional estimate), we calculate whether the point cloud of co-located government-reported vs. farmer-reported yields (Fig. 4) tends to fall above or below the 1:1 line, and by how much. Figure 5 summarizes the results, where the data are arranged both by crop type (aggregating data across all countries), and by country (aggregating data across all crops).

A comparison of farmer-reported vs. government-reported crop yields. In (a), the co-located yield estimates from farmer surveys and regional government statistics are aggregated across all countries and are arranged by crop. In (b), the co-located yield data are aggregated across all crops and instead are split by country. The ‘yield bias’ (y-axis) denotes whether the government-reported yield statistics are systematically higher or lower than the farmer-reported yields. Negative values indicate that farmer-reported yields are lower than government statistics. The mean yield bias (averaged across all countries with available co-located government and farmer survey data) is 11 ± 4.0% (μ ± s.e., where μ is the mean and s.e. is the standard error), indicating that farmer-based estimates are slightly lower than government statistics. In (a,b), the triangles denote the mean yield bias and the boxes denote the 25–75th percentiles of the estimated yield bias. Note that the yield bias is calculated in a total least squares sense. That is, rather than treating either the government-based or the farmer-based yield estimates as a ‘gold-standard’ representation of the true yield, we instead acknowledge that both estimates are flawed representations of the true value. We perform an orthogonal projection of each data point in the government-based yield vs. farmer-based yield crossplots (e.g., see Fig. 4) onto the 1:1 line. Next, we evaluate whether the data cloud tends to sit above or below the 1:1 line, weighting each point observation by it’s orthogonal distance to the 1:1 line and it’s sample size (\(\sqrt{n}\), where n is the number of farmer observations that were aggregated to generate the regional estimate). See Figures S9–S10 in the Supporting Information for the data underlying these yield bias estimates.

Figure 5 shows that there is a systematic bias in which government-reported crop yields are higher than farmer-reported yields. Averaged across all countries with overlapping LSMS-ISA and regional government data (Fig. 5b), the estimated yield bias is +11 ± 4%. Note that the analysis in Fig. 5 shows how farmer survey data and regional government statistics can be harmonized (e.g., bias corrected) in order to leverage both data types for downstream analyses such as calibrating remote sensing algorithms20 or for quantifying the climate sensitivity of agricultural production9. However, Fig. 5 does not indicate whether either data type is an accurate representation of the true yield.

Crop cuts are widely seen as a gold-standard for ground-truth data of crop yields17,20,31. Ideally, a full-plot crop cut would be performed, in which every portion of a farmer’s field is harvested, dried, and weighed20; the total production (harvest weight) divided by the field area encodes the average yield. More common are sub-plot crop cuts, in which a standardized area (e.g., a 4 m × 4 m square) is harvested from a random location on the field. Although sub-plot crop cuts suffer from the limitation that they are sensitive to spatial variability across an individual field20, they still provide an objective and robust ground-truth constraint on crop yields.

Treating crop cuts as the gold-standard, we ask whether the government-reported and farmer-reported yields systematically overestimate or underestimate crop yields relative to the crop cuts. Unfortunately, the LSMS-ISA surveys do not include systematic crop cuts as a component of the data sampling strategy41 (Table 1). However, the Ethiopian agricultural surveys include a large network of crop cuts, with n = 11,345 observations spanning 12 crops. Since Ethiopia falls in the middle of the data distribution with respect to the government-reported vs. farmer-reported yield bias (Fig. 5b), we use the data from Ethiopia as a case study to investigate whether farmer surveys and government statistics produce yield data that are systematically biased relative to crop cuts.

Do farmer surveys and government statistics consistently overestimate or underestimate crop yields?

In Fig. 6, we aggregate all of the crop cuts within an administrative level-1 or level-2 boundary and compare the result to the government-reported yield for the same year. The symbol size in the cross-plots in Fig. 6 represents the number of crop cut observations that were aggregated to the regional level, with larger symbols denoting larger n. Note that the data clouds in Fig. 6c–l fall well above the 1:1 line, indicating that the official government statistics in Ethiopia consistently overestimate crop yields relative to the co-located crop cuts. The mean bias across all crops in the dataset is +32%.

A comparison between the yield estimates derived from field-scale crop cuts and regional government statistics in Ethiopia. The locations of the crop cut observations are shown in (a). (b) A summary of the biases between yield estimates derived from official government statistics vs. crop-cuts; positive values indicate that the government statistics overestimate yield relative to crop-cuts. There are ten crops with sufficient data to make the comparison: (c) barley, (d) beans, (e) groundnuts, (f) maize, (g) millet, (h) sesame, (i) sorghum, (j) soybean, (k) teff, and (l) wheat. All crops show a positive yield bias, indicating that the official government figures overestimate crop yields compared with the ground-truth crop cut data. The mean bias value across all crops is +32% (b). The crossplots in (c)-(k) show the data used to produce the yield bias estimates in (b). Individual data points represent co-located government statistics and field-scale crop-cuts for an individual year. The symbol size denotes the number of crop-cut observations that were aggregated to produce the regional estimate. Circles denote administrative level-2 boundaries and squares denote administrative level-1 boundaries. The inset histograms in (c)-(k) show the data distributions indicating the extent to which the government-based yield estimates are underestimates (negative) or overestimates (positive) of the crop cut data. The histograms are shown from − 100% to +100%.

An equivalent analysis can be performed to compare farmer survey estimates to co-located crop cuts (Fig. 7). Note that, as observed in Fig. 6, the data clouds in Fig. 7c–l fall well above the 1:1 line, indicating that the farmer surveys consistently overestimate crop yields relative to the co-located crop cuts. The mean bias associated with the farmer survey data is +20%, or approximately 12% lower than the bias from the government statistics (Fig. 6). This comparison between the survey and government data in Ethiopia is consistent with the wider set of observations in Fig. 5, which shows that the average bias between the farmer survey and government data (evaluated across a variety of crop types and countries) is 11 ± 4%.

A similar analysis as in Fig. 6, except the crop-cut data are compared to farmer surveys rather than to regional government statistics. The locations of the crop cut and farmer survey data are shown in (a). (b) A summary of the yield biases for the ten crops with sufficient data to make comparisons between the crop cuts and farmer surveys. The positive yield biases across all crops indicate that the yield estimates based on farmer surveys are overestimates relative to the crop cut data. However, the mean bias of +20% is smaller than the yield bias in Fig. 5.

An important implication of Fig. 6 is that official government statistics— which get aggregated to the national scale and eventually are reported by the FAO39— could be overestimates of true, on-the-ground crop yields. So far, only Ethiopia has a sufficiently large network of crop cut observations to perform this analysis. But future surveys (such as those conducted through the 50 × 2030 initiative: https://www.50x2030.org/) could include a crop-cutting protocol in order to test whether the observations in Fig. 6 are widespread.

Evaluating sources of noise (random error) and systematic bias

Although Figs. 6–7 show that there are systematic biases whereby government statistics and household farmer surveys consistently overestimate crop yields relative to crop cuts, these analyses do not reveal the underlying causes of the error. Ultimately, both data types (the official government statistics and the LSMS-ISA survey data) are grounded in household surveys, since the raw data used to inform government statistics are surveys conducted using resident enumerators (e.g. agricultural extension agents or other staff from the Ministry of Agriculture)54. As described by ref. 2, “Farm surveys have been, and still are, the backbone of agricultural statistics in Africa”2. But farmer surveys are susceptible to a host of problems that have been widely acknowledged55 but seldom quantified17,56,57. Here, we leverage the large number of observations in the GROW-Africa database38 to identify and quantify a few key sources of error in the yield statistics generated from household farmer surveys.

In Fig. 8, we consider four questions:

An evaluation of different sources of variability and error in the yield statistics extracted from farmer surveys. We explore four questions: (1) How does the number of farmer observations within a regional administrative boundary affect the quality of the aggregated regional yield estimate? (2) How does the plot area affect the yield estimate? (3) How does the method for estimating the plot area (GPS measurement vs. farmer interview) affect the yield estimate? (4) How does the method for quantifying production (crop cuts vs. farmer interview) affect the yield estimate? To answer each question, we sub-divide the dataset into different groups based on the farmer survey sample size, the field areas, the area measurement methodology, and the crop production measurement methodology (see below for details). We then compare each sub-divided dataset of farmer survey data to the co-located regional government statistics. The top row (a-d) shows the correlation coefficient (ρ) between the farmer survey and government data. The bottom row (e-h) shows the average yield bias between the farmer survey and government data. We define the yield bias the same way as in Fig. 5; negative values indicate that the farmer survey data produce lower yields than the government figures. In (a,d), we divide the dataset of co-located farmer surveys and regional government statistics (e.g., Fig. 4) into four groups based on the number of farmer surveys (n) within the administrative boundary: n≤5, n = 5–20, n = 20–200, and n > 200. In (b,f), we divide the dataset of co-located farmer surveys and regional government statistics according to the plot area (A): A≤0.1 ha, A = 0.1–0.4 ha, A = 0.4–2.0 ha, and A > 2.0 ha. In (c,g), we split the dataset based on whether the farmer surveys used GPS-measured field areas vs. farmer-queried estimates of field areas. In (d,h), we split the dataset between yield estimates based on farmer recall of total production (kg) vs. crop cuts. Note that only Ethiopia has an extensive network of crop cuts (Fig. 6). Cross-plots showing the data underlying this figure are shown in Figure S21 of the Supporting Information.

-

1.

How does the sample size (the number of farmer observations aggregated within a given administrative boundary) affect the yield estimate? We explore how the farmer sample size affects both the correlation (Fig. 8a) and the bias (Fig. 8e) in the relationship between the farmer survey data and the co-located regional government statistics (Fig. 4). The simple statistical expectation is that, as the number of farmer observations (n) increases, the correlation with the regional government data should improve due to a decrease in the noise (random error) in the aggregated estimate. Meanwhile, the average bias (the systematic offset in the farmer-reported and government-reported yields) should not change. This expectation is borne out in Fig. 8a,e.

-

2.

Do average yields vary systematically with field area? Fig. 8b shows that the crop yields estimated from fields arranged from small to large do not show a systematic trend in the degree of correlation with the co-located regional government yields. However, we find that larger fields show a systematically more negative yield bias with respect to the co-located government yields (Fig. 8f). In other words, larger fields appear to have lower average yields, an example of the inverse size–productivity relationship in agriculture18,56,58,59. We explore the causation of this trend (and evaluate whether it is real or an artifact) in the Supplementary Information.

-

3.

How does the method of field area measurement (farmer interview vs. GPS measurement) affect the yield estimate? In the earliest LSMS surveys, field areas were determined principally by asking farmers to self-report the size of each of their plots. However, this method is widely understood to be imperfect since farmers may purposely over- or under-report their land areas due to perceived incentives such as for property taxes or the ability to access to assistance programs2. Unintentional errors also can lead to systematic biases55. For instance, round-off error (the tendency to approximate the field area with a round number)41 is most significant for the smallest parcels2. Consider the example of rounding the field area to the nearest hectare: rounding a 0.8 ha field to 1.0 ha imparts a-25% bias on the resulting yield estimate, whereas rounding a 1.8 ha field to 2.0 ha only imparts a − 5.6% bias on the resulting yield estimate. In response to these critiques, in more recent surveys, the field staff conducting interviews have measured field areas by walking the field boundaries with GPS, providing an objective measure of field area41. In Fig. 8c, we find that the farmer yield estimates using GPS have higher correlation with co-located government statistics. However, we do not observe a systematic bias whereby the yield estimates using GPS are higher or lower than those using recall-based area estimates (Fig. 8g). Figure S19 of the Supplementary Information illustrates why: farmers tend to over-estimate the areas of small plots ( < 0.6 ha), but underestimate the areas of large plots ( > 0.6 ha). When plots of all sizes are combined, these contrasting biases cancel each other out and the resulting yield differences are small (Fig. 8g).

-

4.

How does the method of production quantification (farmer interview vs. crop cut) affect the yield estimate? Regardless of whether field areas are determined via GPS or farmer interview, all LSMS-ISA surveys quantify the total crop production through farmer recall. These recall-based estimates suffer a host of drawbacks. For example, some crops have prolonged harvest seasons. Root crops like cassava store better in the ground, and therefore are harvested in numerous stages drawn out over a period of months2. Bananas likewise are harvested continuously throughout the year2. In addition, what state the crops are measured in (e.g., maize on the cob, or grain in flour)— as well as whether the crops are harvested green— affects the production quantity substantially2. Moreover, production units are non-standardized. For example, harvests are reported in units of ‘bunches’, ‘baskets’, ‘small sacks’, ‘large sacks’, ‘ox carts’, ‘tricycle loads’, ‘truck loads’, etc. (Table 1). Standardization of production units is in part challenged by the fact that the majority of smallholder production is consumed within the household and does not reach the market. A final challenge for the production estimate is intercropping, since it may be challenging to assign areas to the various crops planted within a single plot. Ideally, the relative crop coverage would be calculated based on seeding rates2. In practice, the method used in the LSMS-ISA surveys (Table 1) is to ask the farmers to estimate the relative fraction of each crop that is planted on each plot. These estimates are used to downscale the crop-specific plot area accordingly. In Fig. 8d,h, we compare yield estimates from farmer interviews and objective crop cuts to the co-located regional government yields. We find that the crop cuts produce correlations with the government statistics that are nearly 2 × higher (Fig. 8d). Meanwhile, consistent with Fig. 6, the crop cuts indicate yields that are ~ 30% lower than the co-located government statistics (Fig. 8h).

Usage Notes

Below, we illustrate two use cases for the GROW-Africa database: (1) resolving the spatio-temporal patterns in crop yields across Africa, and (2) using the database to train machine learning algorithms to quantify crop yields from satellite data.

A half-century of yield trends across Africa

Figure 9 shows the regional changes in crop area, production, and yields over the last 50 years (1973-2022) for eight of the crops included in the GROW-Africa database. Although agricultural statistics often are reported in terms of total production, the focus on production obscures the relative contributions from productivity gains (i.e., yield improvements) vs. increases in cropland area. Figure 9 decomposes the trends in total production into the relative contributions from area expansion and yield gains. For all crops except sugarcane (which is principally grown in Northern Africa), the vast majority ( ~ 70–90%) of the increases in crop production over the last 50 years have been attributed to area extensification rather than yield gains (Fig. 9).

Regional decomposition of 50 years of production, area, and yield patterns for eight key crops in Africa: (a) maize, (b) sorghum, (c) cassava, (d) groundnuts, (e) rice, (f) cowpea, (g) sweet potatoes, and (h) sugarcane. The data span the period 1973-2022. Note that the yield values (production divided by harvested area) are smoothed with a 10-year moving mean. The yield panels also exclude northern Africa, which appears off-scale (significantly higher yield) with respect to the other regions. The central panel (i) summarizes the 5-decade-long trends in production, area, and yield. Although the total production of most crops has increased at rates of approximately 20–30% per decade, these production gains are accomplished principally through increases in harvested area (i.e., crop extensification) rather than through increases in crop yields. Typical increases in crop yields over the past 50 years are approximately 10% per decade or lower.

Figure 9 also reveals how, even as the average yields across the continent have been increasing steadily (Fig. 1a,b), yield gains are distributed unequally across regions. For example, average maize yields across sub-Saharan Africa have increased from 1.4 Mg/ha in 1980 to 2.1 Mg/ha in 2020 (a +50% gain), but much of this growth is driven by southern Africa; average maize yields have not changed appreciably in central Africa over the last 40 years (Fig. 9).

Application for satellite-based estimates of agricultural production

Despite aggregating over half a million observations, the GROW-Africa database38 has significant gaps across space and time (see Figures S3–S5). Therefore, complete wall-to-wall inventories of crop yields across the continent will rely on remotely-sensed indicators17,20,31. Here, we provide one example workflow for how the data in the GROW-Africa database38 can be leveraged to train machine learning algorithms to estimate crop yields from satellite data.

A note on spatial heterogeneity and the granularity of satellite-based estimates

An important consideration for the design of a satellite crop yield mapper is spatial resolution. Ideally, the spatial footprint of the satellite observations should match the footprint of the ground-truth yield observations. In this context, local heterogeneity creates a widely-recognized and ongoing challenge in the realm of remote sensing of smallholder agriculture17,20,30,31,37. As an illustration, Fig. 10 compares agricultural regions from the United States, Senegal, and Ethiopia. Each row illustrates the spatial footprint (pixel size) of a satellite dataset commonly used for agricultural monitoring: (i) The 5 km × 5 km footprint in the top row of Fig. 10 is representative of a pixel in the GOSIF27 dataset. (ii) The 250 m × 250 m footprints in the middle row of Fig. 10 are representative of the pixel size in Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) imagery60. (iii) The 30 m × 30 m square in the bottom row of Fig. 10 depicts the size of a single Landsat pixel. Note how, in the example from the United States (Fig. 10a), the cropland encapsulated in a single Landsat pixel is homogeneous. In contrast, the 30 m x 30 m Landsat pixels in the examples from Senegal and Ethiopia include a mixture of cultivated land, trees, roads, and houses. Thus, practitioners interested in resolving field-scale crop yields30,31 principally rely on high spatial-resolution microsatellite data17,30 (e.g., satellite datasets with spatial resolutions ≤5 m, and as fine as ≤1 m). But such fine-scale analyses require enormous satellite datasets, rendering continent-wide analyses prohibitive without having access to substantial computational and data storage infrastructure. For example, continent-wide yield mapping based on 1-m-resolution RGB imagery31 requires a dataset that is 75,000,000 times larger than a mapping effort based on 5-km-resolution GOSIF27 pixels.

An illustration of spatial heterogeneity and spatial scale for three different agricultural regions: (a) Illinois, USA (40.31489∘N, 88.41142∘W), (b) Senegal (13.246984∘N, 15.569503∘W), and (c) Ethiopia (9.783614∘N, 37.533314∘E). The top row shows a 5 km × 5 km footprint, which is representative of the size of a single pixel in the GOSIF27 dataset used in Fig. 13. The middle row shows example tiles that each are 250 m × 250 m, which is representative of the size of a single pixel in Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) imagery60. The bottom row zooms in on the central 250 m x 250 m tile from the middle row and illustrates the size of a 30 m × 30 m Landsat pixel (see the white boxes in the lower-left corners).

In addition to the computational and data storage constraints, fine-scale yield mapping from satellite imagery is best-posed when the ground-truth yield observations have the spatial footprints (and geolocation accuracies) as the representative pixel size of the satellite imagery. However, ground-truth yield observations such as those compiled in the GROW-Africa database fall short of this ideal in numerous ways— perhaps most importantly because of the spatial anonymization step performed to survey data before public release in which survey clusters are randomly displaced (jittered) by a distance of 0–5 km48,49. Thus, point observations from the LSMS-ISA surveys, for example, cannot be directly linked to an individual point on the ground (at least not with uncertainties less than the scale of ± 5 km). However, all of the farmer survey observations within a ± 5 km zone (or, at coarser scales such as the level of an administrative level-1 or level-2 boundary) can be aggregated to produce a regional estimate. Note that these regional ground-truth yield constraints describe geographic areas that are larger than individual pixels in a satellite dataset. Thus, leveraging these types of regional data for the training of remote sensing algorithms requires a workflow for aggregating many satellite pixels in a way that maintains the structure and heterogeneity in the underlying data. We describe such a workflow below.

Example workflow: building a satellite yield estimator for maize

We design and train a simple neural network to quantify regional maize yields in Africa. We use regional government statistics from the GROW-Africa database38 as our ground-truth for model training and evaluation (Fig. 11). Aggregated farmer survey data could be used instead of (or in addition to) the regional government data. However, if both data sources are used simultaneously, we recommend first applying the bias corrections summarized in Fig. 5 in order to harmonize these two datasets. The satellite data we use as input for the neural network is GOSIF27. GOSIF is an empirical estimate of the solar-induced fluorescence (SIF) produced by photosynthesizing vegetation25,26,61. SIF has been shown to be a strong and robust proxy for crop yields61,62,63. There is no direct retrieval of SIF with global coverage over the historical period considered here (2000-2022), so we instead use the GOSIF product, which uses SIF retrievals from the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2)26 and co-located MODIS observations to train a machine learning algorithm to estimate SIF from MODIS data and meteorological reanalysis27. The GOSIF dataset therefore can leverage the unparalleled spatial and temporal coverage of the MODIS mission to produce global maps of SIF at 0.05 × 0.05 degree (approximately 5 × 5 km) spatial resolution and 8-day temporal resolution (producing ~ 45 observations per year) over the period 2000–present27.

An illustration of the ground-truth dataset (a subset of the GROW-Africa database) used to train the neural network in Fig. 14. Here, we show just the sub-national government yield statistics for maize over the period 2000-2022. In (a)-(c), the sub-national administrative boundaries (level 1 and level 2) are color-coded according to: (a) the number of years for which we have observations during the period 2000-2022, (b) the average yield value (metric tons (megagram, Mg) per hectare), and (c) the estimated fraction of the total administrative boundary that is cultivated with maize. In (c), the area fraction is determined by calculating the ratio between the reported region-total harvested area (hectares) by the total land area within the administrative boundary. Gray regions denote no data.

Figure 12 illustrates the annual SIF cycle over the cropland areas used in the dataset shown in Fig. 11. The phenologies in Fig. 12 clearly resolve the varied crop calendars from country to country. In order to collate and standardize data from all countries, we define country-specific crop calendars by taking 12-month windows that start and end at the time in the year with the minimum average SIF. Figure 12 represents each country-specific crop calendar with a shaded gray rectangle. Using country-specific crop calendars successfully corrects for the phase offsets in the SIF phenologies shown in Fig. 12 (e.g., due to differences in latitude, rainfall regime, and farmer practices), and allows the input data for the neural network described below to be standardized and normalized (see Figure S25).

Constructing country-specific agricultural calendars using annual timeseries of solar-induced fluorescence (SIF) over croplands. The plotted timeseries show two sequential annual cycles (January–December). All sub-Saharan African countries with data in the ground-truth dataset in Fig. 11 are shown. The timeseries are calculated by averaging the GOSIF27 observations (8-day repeat interval) over the period 2000-2022. To compute the weighted average SIF value (y-axis), the GOSIF pixels (0.05 × 0.05 degree) are weighted by the estimated fraction cropland within that pixel, based on the cropland mask from Digital Earth Africa (Figure S23). Note that the timing (phase) of the annual SIF cycles varies from country to country, in accordance with changes in latitude and rainfall regime. Many countries in eastern Africa have two distinct SIF cycles each year denoting separate agricultural seasons. In order to harmonize and facilitate comparison between the different country-level datasets, we define a country-specific agricultural calendar that is defined as starting and ending at the time of year with the minimum average SIF value. That is, the period of peak SIF (and therefore inferred crop growth) is located in the middle of each 12-month agricultural calendar. The country-specific calendars are denoted with gray rectangles, and the subplot titles report the day of year (DOY) when the calendar starts. Shifting each country’s average SIF curve by the calendar start date makes the country-level datasets collapse onto a similar, standardized shape (Figure S25).

To implement our satellite yield mapper, we first assemble the stack of m = 45 GOSIF observations from each year (Fig. 13). Next, we aggregate all of the pixels that fall within a sub-national administrative boundary into a histogram of bin counts (here we use l = 32 bins, where bin #1 represents the lowest pixel-level SIF values and bin #l represents the highest pixel-level SIF values). The result of the data pre-processing steps outlined in Fig. 13 is that each administrative boundary with a yield constraint in the ground-truth dataset in Fig. 11 is assigned a 32 × 45 matrix that represents the annual SIF timeseries for all of the pixels encapsulated in that geographic region. Each pixel-level observation within the administrative boundary can be weighted by an estimate of the relative cropland fraction in that region, in order to up-weight croplands and down-weight forests and developed areas (see Figure S23).

An illustration of a workflow for aggregating remote sensing data (in this case, timeseries of 0.05 × 0.05 degree GOSIF27 observations) to a scale that can be compared with region-level crop yields (for which there are available ground-truth data in the form of sub-national government statistics— see Fig. 11). (a) Each region (e.g., sub-national administrative boundary) covers a zone of n pixels in a satellite dataset. (b) The satellite dataset may have m repeat observations throughout the growing season or year. In this case, we use the 0.05 × 0.05 degree GOSIF27 observations as an example remote sensing dataset. GOSIF has a repeat interval of 8 days (corresponding to m = 45 observations for a full annual cycle). (c) For each of the m time slices, the n pixel-level observations within the region of interest can be binned into a histogram of l bins (where bin #1 represents the lowest pixel values and bin #l represents the highest pixel values). This binning step allows for regions with different areas (and therefore different numbers n of enclosed pixels) to be standardized to produce a remote sensing timeseries with common dimensions of l × m. The matrices in (c) are normalized such that the sum of each column is 1. These matrices are used as the input for neural network shown in Fig. 14. Note that the l × m × 1 matrices shown in (c) could instead be l × m × c matrices, where c is the number of channels (i.e., multiple remote sensing datasets representing different color bands in a multispectral satellite image or climate data such as temperature, precipitation, soil moisture, etc.).

The 32 × 45 matrices illustrated in Fig. 13 serve as the input to our neural network. We use a simple feed-forward neural network architecture (see section 3 of the Supplementary Information for a full description of the architecture). Figure 14 shows the model performance, evaluated both on the 80% of the dataset (Fig. 11) used to train the model, and on the random 20% of the dataset held-out from model training and used to test the model. Note that the correlation between the yield values predicted from the neural network and the ground-truth yields from government statistics is only ρ = 0.46 for the held-out test dataset (Fig. 14b). However, a considerable source of the noise in Fig. 14 could be the imperfect (noisy) nature of the ground-truth data17,31. The results in Fig. 14 are as good as the best satellite-based approaches for measuring smallholder yield in the literature17.

Results of the simple feed-forward neural network used to estimate maize yields based on annual timeseries of GOSIF27 observations (Fig. 13). The neural network is trained and tested on the Africa-wide ground-truth dataset shown in Fig. 11. The testing data represents a random 20% of the dataset not used to train the model. The value ρ(x, y) denotes the correlation coefficient between the predicted yield from the neural network and the government-reported yield. Due to the large number of data points, the data are grouped into equally-spaced bins and are represented based on their binned mean values (squares), 25-75th percentiles (thick lines), and 10-90th percentiles (thin lines).

We can apply the trained neural network in Fig. 14 to any region in Africa (or to the whole continent). Figure 15 shows an illustration of the trained network applied to Nigeria over the period 2002-2021. Even though the network is trained on data from Africa as a whole, the yield estimates in Fig. 15 produce national-level maize yield inventories that have a mean absolute difference of just 0.17 Mg/ha compared to the FAO-reported national maize yields in Nigeria39. Finally, note that the model was trained end-to-end and evaluated on a personal laptop computer, so it does not require extensive computational resources.

Maps of estimated maize yields in Nigeria over the period 2002-2021 based on applying the neural network in Fig. 14. Equivalent estimates could be created for any other country (or for all of Africa) using the same neural network approach. The maps are displayed with a transparency layer that represents the estimated cropland area fraction, such that regions with no croplands appear transparent and regions with abundant croplands appear opaque. See Figure S24 in the Supporting Information for the cropland area estimates.

Limitations of the GROW-Africa database

Although GROW-Africa38 presents a substantial increase in the availability of spatially-disaggregated and harmonized crop yield observations in Africa, there remain a number of ongoing challenges and limitations of the dataset. Three of the most important limitations include: (1) data quality, (2) spatial jitter in survey data, and (3) spatial and temporal gaps in coverage. First, household farmer survey data are abundant (for example, LSMS survey data constitute n = 195,152 (36%) of the observations in the GROW-Africa database), but these data also are notoriously noisy2,17,54,56,57. Efforts to generate a more limited number of high-quality ground-truth observations (e.g., through crop-cuts or full plot harvests) could make a profound improvement not only on our ability to develop high-quality remote sensing models20,31, but also on the ability to properly evaluate the accuracy of such models17,20,31. Second, the spatial jitter of 0–5 km applied to farmer survey datasets48,49 (for privacy considerations) limits the utility of these datasets for calibrating high-resolution satellite-based yield mappers29,31,50. However, as illustrated in Fig. 13, the jittered survey observations can be aggregated to the ~ 5 km scale and then used to train a satellite-based yield mapper at the same ~ 5-km scale. Lastly, there remain major data gaps across space and time (see Fig. 11 and Figures S3–S5 of the Supplementary Information). Generating accurate wall-to-wall estimates of crop yields requires particular attention to filling in these spatial data gaps (Fig. 11).

Future directions with GROW-Africa

Earth Observation satellites are rapidly transforming our ability to monitor agricultural production from space. But the ever-expanding capabilities of satellites are rendering high-quality georeferenced ground-truth data more important, not less17. The GROW-Africa database compiles n = 535,844 georeferenced yield observations for 25 crops in Africa to provide a baseline dataset that can be used to train remote sensing algorithms. For example, most of the existing gridded crop yield datasets64,65,66,67 are based on spatially-partitioning (allocating)68 the coarse national-level yield data from the FAO39. In contrast, granular ground-truth datasets such as the GROW-Africa database38 can enable a new generation of data-driven crop yield maps that are based on bottom-up estimates constrained by remote sensing observations. Finally, the GROW-Africa database38 also can be leveraged on its own to evaluate historical yield trends (Fig. 9) and their dependencies on climate variability6,7,9,10,12, climate extremes11,69, political circumstances13,36, agronomic practices14,15,16,70, and infrastructure development71,72,73, to name a few.

Code Availability

The code developed for processing and cleaning the data presented in this study, along with the full GROW-Africa database, is available on Zenodo38: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14961637.

References

Davis, B., Di Giuseppe, S. & Zezza, A. Are African households (not) leaving agriculture? Patterns of households’ income sources in rural Sub-Saharan Africa. Food Policy 67, 153–174 (2017).

Carletto, C., Jolliffe, D. & Banerjee, R. The Emperor has no data! Agricultural statistics in sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank Working Paper 565 (2013).

Ligon, E. A. & Sadoulet, E. Estimating the effects of aggregate agricultural growth on the distribution of expenditures. CUDARE Working Papers (2011).

Liu, J., Wennberg, P. O., Parazoo, N. C., Yin, Y. & Frankenberg, C. Observational constraints on the response of high-latitude northern forests to warming. AGU Advances 1, e2020AV000228 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Elucidating climatic drivers of photosynthesis by tropical forests. Global Change Biology (2023).

Anderson, W. et al. Preseason maize and wheat yield forecasts for early warning of crop failure. Nature Communications 15, 7262 (2024).

Anderson, W., Seager, R., Baethgen, W., Cane, M. & You, L. Synchronous crop failures and climate-forced production variability. Science Advances 5, eaaw1976 (2019).

Mechiche-Alami, A. & Abdi, A. M. Agricultural productivity in relation to climate and cropland management in West Africa. Scientific Reports 10, 1–10 (2020).

Ray, D. K., Gerber, J. S., MacDonald, G. K. & West, P. C. Climate variation explains a third of global crop yield variability. Nature Communications 6, 5989 (2015).

Lobell, D. & Lee, R. Stagnant crop productivity growth in southern Africa despite moderate climate trends. ResearchSquare (https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-4344936/v1) (2024).

Lesk, C., Rowhani, P. & Ramankutty, N. Influence of extreme weather disasters on global crop production. Nature 529, 84–87 (2016).

Lesk, C. et al. Stronger temperature–moisture couplings exacerbate the impact of climate warming on global crop yields. Nature Food 2, 683–691 (2021).

Anderson, W. et al. Violent conflict exacerbated drought-related food insecurity between 2009 and 2019 in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature Food 2, 603–615 (2021).

Corbeels, M., Naudin, K., Whitbread, A. M., Kühne, R. & Letourmy, P. Limits of conservation agriculture to overcome low crop yields in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature Food 1, 447–454 (2020).

Jain, M. et al. The impact of agricultural interventions can be doubled by using satellite data. Nature Sustainability 2, 931–934 (2019).

Aramburu-Merlos, F. et al. Adopting yield-improving practices to meet maize demand in Sub-Saharan Africa without cropland expansion. Nature Communications 15, 4492 (2024).

Burke, M., Driscoll, A., Lobell, D. B. & Ermon, S. Using satellite imagery to understand and promote sustainable development. Science 371, eabe8628 (2021).

Banerjee, R. et al. From tragedy to renaissance: improving agricultural data for better policies. Tech. Rep., The World Bank (2015).

Yeh, C. et al. Using publicly available satellite imagery and deep learning to understand economic well-being in Africa. Nature Communications 11, 2583 (2020).

Lobell, D. B. et al. Eyes in the sky, boots on the ground: Assessing satellite-and ground-based approaches to crop yield measurement and analysis. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 102, 202–219 (2020).

Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) Satellite Database. [Data set: Last accessed 01 May 2023]. https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/satellite-database.

Vermote, E. MODIS/Terra Surface Reflectance 8-Day L3 Global 500m SIN Grid V061 [Data set]. Tech. Rep., NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (2021).

Running, S., Mu, Q. & Zhao, M. MODIS/Terra Gross Primary Productivity 8-Day L4 Global 500m SIN Grid V061 [Data set]. Tech. Rep., NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (2021).

Myneni, R., Knyazikhin, Y. & Park, T. MODIS/Terra+Aqua Leaf Area Index/FPAR 8-Day L4 Global 500m SIN Grid V061 [Data set]. Tech. Rep., NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (2021).

Frankenberg, C. et al. New global observations of the terrestrial carbon cycle from GOSAT: Patterns of plant fluorescence with gross primary productivity. Geophysical Research Letters38 (2011).

Sun, Y. et al. Overview of Solar-Induced chlorophyll Fluorescence (SIF) from the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2: Retrieval, cross-mission comparison, and global monitoring for GPP. Remote Sensing of Environment 209, 808–823 (2018).

Li, X. & Xiao, J. A global, 0.05-degree product of solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence derived from OCO-2, MODIS, and reanalysis data. Remote Sensing 11, 517 (2019).

O’Neill, P. E. et al. SMAP Enhanced L2 Radiometer Half-Orbit 9 km EASE-Grid Soil Moisture. (SPL2SMP_E, Version 5). [Data Set]. Tech. Rep., NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center (2021).

Lobell, D. B., Thau, D., Seifert, C., Engle, E. & Little, B. A scalable satellite-based crop yield mapper. Remote Sensing of Environment 164, 324–333 (2015).

Jain, M. et al. Mapping smallholder wheat yields and sowing dates using micro-satellite data. Remote Sensing 8, 860 (2016).

Burke, M. & Lobell, D. B. Satellite-based assessment of yield variation and its determinants in smallholder African systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 2189–2194 (2017).

Azzari, G., Jain, M. & Lobell, D. B. Towards fine resolution global maps of crop yields: Testing multiple methods and satellites in three countries. Remote Sensing of Environment 202, 129–141 (2017).

You, J., Li, X., Low, M., Lobell, D. & Ermon, S. Deep Gaussian process for crop yield prediction based on remote sensing data. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 31 (2017).

Azzari, G., Jain, S., Jeffries, G., Kilic, T. & Murray, S. Understanding the requirements for surveys to support satellite-based crop type mapping: Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. Remote Sensing 13, 4749 (2021).

Lee, D. et al. Maize yield forecasts for Sub-Saharan Africa using Earth observation data and machine learning. Global Food Security 33, 100643 (2022).

Wuepper, D., Wang, H., Schlenker, W., Jain, M. & Finger, R. Institutions and global crop yields. Tech. Rep., National Bureau of Economic Research (2023).

Wüpper, D. et al. Satellite data in agricultural and environmental economics: Theory and practice. 32nd International Conference of Agricultural Economists (2024).

Geyman, E. et al. GROW-Africa (Groundtruthing Remote-sensing for Optimizing Yield in Africa) Database, v1.0 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14961637 (2025).

FAOSTAT: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Statistics. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/.

Lee, D. et al. HarvestStat Africa–harmonized subnational crop statistics for sub-Saharan Africa. Scientific Data 12(1), 690 (2025).

Carletto, C., Savastano, S. & Zezza, A. Measurement, farm size and productivity. Living Standards Measurement Study Brief Series (2013).

Waha, K., Zipf, B., Kurukulasuriya, P. & Hassan, R. M. An agricultural survey for more than 9,500 African households. Scientific Data 3, 1–8 (2016).

Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia. Ethiopia Socioeconomic Survey (ESS4) 2018-2019. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024].World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/k739-c548.

Agro-MAPS: Global Spatial Database of National and Sub-National Agricultural Land-Use Statistics. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Geospatial Unit (NSL). https://gaez.fao.org/pages/agromaps.

ReSAKSS (Regional Strategic Analysis and Knowledge Support System): Country eAtlases. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. http://eatlas.resakss.org.

Lee, D. & Anderson, W. HarvestStat: Harmonized subnational crop statistics. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. https://github.com/HarvestStat/HarvestStat (2024).

Dillon, A., Carletto, G., Gourlay, S., Wollburg, P. & Zezza, A. Agricultural survey design: lessons from the LSMS-ISA and beyond, LSMS Guidebook. The World Bank (Washington DC) (2021).

Blankespoor, B., Croft, T., Dontamsetti, T., Mayala, B. & Murray, S. Spatial anonymization: Guidance note prepared for the inter-secretariat working group on household surveys. Tech. Rep., United Nations Department Of Economic and Social Affairs: Statistics Division (2021).

Michler, J. D., Josephson, A., Kilic, T. & Murray, S. Privacy protection, measurement error, and the integration of remote sensing and socioeconomic survey data. Journal of Development Economics 158, 102927 (2022).

Deines, J. M., Patel, R., Liang, S.-Z., Dado, W. & Lobell, D. B. A million kernels of truth: Insights into scalable satellite maize yield mapping and yield gap analysis from an extensive ground dataset in the US Corn Belt. Remote Sensing of Environment 253, 112174 (2021).

USAID. Kaduna State Agricultural Production Data. Dataset. USAID Development Data Library https://data.usaid.gov/d/ieyj-ibbd (2019).

Aramburu Merlos, F. et al. Maize management and yield of smallholder farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa between 2016 and 2022 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11122388 (2024).

USAID. Gross Margin Survey Data for an Agricultural Project in Zimbabwe: 2012 Data. Dataset. USAID Development Data Library https://data.usaid.gov/d/dw7v-yfvg (2020).

Beegle, K., Carletto, C., Himelein, K. & Kastelic, K. H. Reliability of recall in agricultural data. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (2011).

Carletto, C., Savastano, S. & Zezza, A. Fact or artifact: The impact of measurement errors on the farm size–productivity relationship. Journal of Development Economics 103, 254–261 (2013).

Gourlay, S., Kilic, T. & Lobell, D. Could the debate be over? Errors in farmer-reported production and their implications for the inverse scale-productivity relationship in Uganda. Errors in Farmer-Reported Production and Their Implications for the Inverse Scale-Productivity Relationship in Uganda (September 12, 2017). World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (2017).

Adzawla, W. et al. Accuracy of agricultural data and implications for policy: Evidence from maize farmer recall surveys and crop cuts in the Guinea Savannah zone of Ghana. Agricultural Systems 214, 103817 (2024).

Desiere, S. & Jolliffe, D. Land productivity and plot size: Is measurement error driving the inverse relationship? Journal of Development Economics 130, 84–98 (2018).

Gourlay, S., Kilic, T. & Lobell, D. B. A new spin on an old debate: Errors in farmer-reported production and their implications for inverse scale-Productivity relationship in Uganda. Journal of Development Economics 141, 102376 (2019).

MCST. (MODIS Characterization Support Team). MODIS 250m Calibrated Radiances Product [Data set]. Tech. Rep., NASA MODIS Adaptive Processing System, Goddard Space Flight Center, USA (2017).

Guanter, L. et al. Global and time-resolved monitoring of crop photosynthesis with chlorophyll fluorescence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, E1327–E1333 (2014).

Guan, K. et al. Improving the monitoring of crop productivity using spaceborne solar-induced fluorescence. Global Change Biology 22, 716–726 (2016).

He, L. et al. From the ground to space: Using solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence to estimate crop productivity. Geophysical Research Letters 47, e2020GL087474 (2020).

Yu, Q. et al. A cultivated planet in 2010 - Part 2: The global gridded agricultural production maps. Earth System Science Data Discussions 2020, 1–40 (2020).

Iizumi, T. & Sakai, T. The global dataset of historical yields for major crops 1981–2016. Scientific Data 7, 97 (2020).

Grogan, D., Frolking, S., Wisser, D., Prusevich, A. & Glidden, S. Global gridded crop harvested area, production, yield, and monthly physical area data circa 2015. Scientific Data 9, 15 (2022).

Qin, X., Wu, B., Zeng, H., Zhang, M. & Tian, F. Global Gridded Crop Production Dataset at 10 km Resolution from 2010 to 2020. Scientific Data 11, 1377 (2024).

You, L., Wood, S., Wood-Sichra, U. & Wu, W. Generating global crop distribution maps: From census to grid. Agricultural Systems 127, 53–60 (2014).

Reed, C. et al. The impact of flooding on food security across Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119, e2119399119 (2022).

Krishna, V. V. et al. Impacts of CGIAR maize improvement in sub-Saharan Africa 1995-2015 (2021).

Asher, S., Campion, A., Gollin, D. & Novosad, P.The long-run development impacts of agricultural productivity gains: Evidence from irrigation canals in India (Centre for Economic Policy Research London, UK, 2022).

Schmitt, R. J., Rosa, L. & Daily, G. C. Global expansion of sustainable irrigation limited by water storage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119, e2214291119 (2022).

Rosa, L. et al. Regional irrigation expansion can support climate-resilient crop production in post-invasion Ukraine. Nature Food 5, 684–692 (2024).

Institut National de la Statistique et de l’Analyse Économique (INSAE) (Gouvernement du Benin). Enquête Harmonisée sur le Conditions de Vie des Ménages, 2021-2022 [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/6272/.

Institut National de la Statistique et de l’Analyse Économique (INSAE) (Gouvernement du Benin). Enquête Harmonisée sur le Conditions de Vie des Ménages, 2018-2019 [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/RN3K-Z374.

Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie (INSD), Enquête Harmonisée sur le Conditions de Vie des Ménages, Burkina Faso 2021-2022. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/6277.

Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie (INSD), Enquête Harmonisée sur le Conditions de Vie des Ménages, Burkina Faso 2021/22 - Panel Survey [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/6224.

Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie (INSD), Enquête Harmonisée sur le Conditions de Vie des Ménages, Burkina Faso 2018-2019 [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/wv88-j486.

Institut National de la Statistique (INS) (Gouvernement du Côte d’Ivoire). Côte d’Ivoire - Enquête Harmonisée sur le Conditions de Vie des Ménages, 2021-2022. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/6273.

Institut National de la Statistique (INS) (Gouvernement du Côte d’Ivoire). Côte d’Ivoire - Enquête Harmonisée sur le Conditions de Vie des Ménages, 2018-2019. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/8wh3-bf40.

Ethiopian Statistical Service. Ethiopia Socioeconomic Panel Survey, Wave 5 (ESPS-5) 2021-2022. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/6161.

Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia. Ethiopia Socioeconomic Survey,Wave 3 (ESS3) 2015-2016. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/ampf-7988.

Central Statistics Agency of Ethiopia (CSA) & Living Standards Measurement Study Integrated Surveys of Agriculture (LSMS-ISA). Socioeconomic Survey 2013-2014. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/mccp-y123.

Central Statistical Agency & Living Standards Measurement Study Team. Rural Socioeconomic Survey 2011-2012. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/80xt-9m68.

Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE) (Governo da Guiné-Bissau). Guinea Bissau - Inquérito Harmonizado sobre as Condiçöes de vide dos Agreagados Familiares, 2021-2022. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/6274.

Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Inquérito Harmonizado sobre as Condiçöes de vide dos Agreagados Familiares 2018-2019. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/1ekb-m086.

National Statistical Office (NSO). Fifth Integrated Household Survey 2019-2020. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/mpyk-ds48.

National Statistical Office (NSO). Fourth Integrated Household Survey 2016-2017. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/g2p9-9r19.

National Statistical Office (NSO). Third Integrated Household Survey 2010-2011. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/w1jq-qh85.

Institut National de la Statistique (INSTAT) (Gouvernement du Mali). Mali - Enquête Harmonisée sur le Conditions de Vie des Ménages, 2021-2022. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/6275.

Institut National de la Statistique (INSTAT). Enquête Harmonisée sur le Conditions de Vie des Ménages 2018-2019. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/90e9-4e91.

Planning and Statistics Unit, National Institute of Statistics & National Directorate of Agriculture. Integrated Agricultural Economic Survey 2014. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/qqam-mn86.

Institut National de la Statistique (INS) (Gouvernement du Niger). Niger - Enquête Harmonisée sur le Conditions de Vie des Ménages, 2021-2022. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/6276.

Survey and Census Division. National Survey on Household Living Conditions and Agriculture 2014, Wave 2 Panel Data. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/3xnb-sd96.

Survey and Census Division, National Institute of Statistics. National Survey on Household Living Conditions and Agriculture 2011. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/bp16-s524.

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). General Household Survey, Panel 2018-2019, Wave 4. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/1hgw-dq47.

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). General Household Survey, Panel 2015-2016, Wave 3. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/7xmj-q133.

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). General Household Survey, Panel 2012-2013, Wave 2. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/kxpy-aa72.

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). General Household Survey, Panel 2010-2011, Wave 1. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/y9e2-b753.

Agence National de la Statistique et de la Démographie (ANSD) (Gouvernement du Senegal). Senegal - Enquête Harmonisée sur le Conditions de Vie des Ménages, 2021-20122. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/6278.

Agence National de la Statistique et de la Démographie (ANSD). Enquête Harmonisée sur le Conditions de Vie des Ménages 2018-2019. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/hhhx-j012.

National Bureau of Statistics (Ministry of Finance and Planning). Tanzania - National Panel Survey 2020-21, Wave 5. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/5639.

National Bureau of Statistics (Ministry of Finance and Planning). Tanzania - National Panel Survey 2019-2020 - Extended Panel with Sex Disaggregated Data. [Data set: Last accessed 18 September 2024]. World Bank, Development Data Group. https://doi.org/10.48529/0y7d-1v78.