Abstract

Submarine landforms are a critical component of Earth’s geomorphology, essential for understanding marine geological evolution, ocean dynamics, and marine ecosystems. However, global-scale classification of submarine landforms has been constrained by the lack of high-resolution data and insufficient integration of terrain knowledge. In response to these challenges, we propose a terrain knowledge-based submarine landform framework, which considers morphological features, spatial relations and undulating characteristics. Utilizing the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans at 15 arc second, a dataset of global submarine landform (GSL) is produced. The dataset includes the submarine landforms with 6 landform zones and 21 landform types, which reveals the diversity and complexity of submarine landforms. The comparison with existing 30 arc second global seafloor feature maps reveals that our dataset can reflect more detailed regional characteristics of the seafloor geomorphology. This dataset is the first global scale submarine landform dataset at 15 arc second, which offers a new perspective on submarine landforms, providing key insights into seafloor geology, morphology, and dynamic processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The ocean covers 71% of the Earth’s surface, spanning approximately 362 million square kilometers1,2. The submarine landforms located at the ocean floor are “unseen” landscapes, but they are also the major component of Earth’s geomorphology3,4. These landforms are of great significance for understanding the history and processes of submarine geological activities, such as plate tectonics, sediment deposition, and volcanic activity5,6, while also exerting profound influences on ocean dynamics, ecosystem distribution, and resource formation2,7,8,9,10,11,12. Submarine landforms exhibit remarkable complexity and diversity, ranging from flat abyssal plains to steep mid-ocean ridges and various seamounts13,14. Different landforms not only display distinct morphological characteristics but also demonstrate certain clustering effects15,16,17. Similar morphological features tend to be spatially aggregated, while significant differences exist between regions, reflecting the spatial heterogeneity of submarine landforms18. Based on these characteristics, submarine landforms can be zoned and classified, providing deeper insights into their formation mechanisms and evolutionary processes.

With the continuous development of seafloor exploration technologies, there have been qualitative leaps in the understanding of submarine landforms. Understanding of submarine landforms has evolved alongside the continuous development4. Early representations of submarine topography were based on low-resolution bathymetric data, which, while capable of depicting basic morphological features, lacked the detail necessary to capture finer characteristics of the seafloor19. However, with advancements in multibeam sonar systems, satellite altimetry, and other seafloor mapping techniques, the resolution, accuracy, and coverage of bathymetric data have significantly improved20,21,22,23,24. Today, high-resolution global bathymetric datasets, such as those with 15 arc-second resolutions, provide comprehensive and detailed representations of submarine landforms25,26,27,28. These datasets not only enable the representation of morphological features but also facilitate the quantification of their characteristics, offering a robust foundation for the zoning and classification of global submarine landforms. Such high-resolution data are indispensable for advancing our understanding of submarine geomorphology and supporting quantitative studies of seafloor features.

Quantitative bathymetric analysis methods have evolved as the availability of bathymetric data has increased29. Submarine terrain analysis has developed its own distinct paradigms, establishing foundational approaches for quantitative analysis of submarine topography3,30,31,32. These approaches incorporate the characteristics of submarine landforms to construct terrain derivatives or indices suitable for capturing seafloor features33,34,35,36. These bathymetric derivatives, such as bathymetric position index (BPI), have been widely applied in fields, such as habitat mapping and the study of the morphological features of marine reserves31,37,38,39. The classification of submarine landforms is becoming more refined and applicable to larger datasets thanks to semi-automated methods40,41,42,43; however, applications at a global scale remain insufficient. Although Harris et al.44 have produced the first digital global map of seafloor geomorphic features, the classification process still involved considerable manual delineation. Thus, data resolution and the application of quantitative methods can still be improved.

Terrain knowledge, representing the semantic descriptions of topographic characteristics across various environments, has been widely applied in both terrestrial and marine geomorphology studies45,46,47,48,49,50,51. Building upon these important foundations, our study introduces a novel regional zoning perspective to further advance the application of terrain knowledge in submarine landform classification. While previous works have established fundamental frameworks for marine geomorphology characterization44,50,51, this study focuses specifically on developing an integrated approach that combines terrain knowledge with quantitative analysis methods for automated seafloor zoning and classification. This approach aims to complement existing methodologies by providing new insights into the systematic organization of submarine landforms at regional scales, particularly for handling the growing volume of medium-to-high resolution bathymetric data with global coverage.

In this study, we have achieved terrain knowledge-driven zoning and classification of global submarine landforms. During the classification process, we incorporated key terrain knowledge, including morphological features, spatial relations, and undulating characteristics of submarine topography. Leveraging this knowledge, we developed a global submarine landform classification system that reflects the morphology, undulation, and spatial heterogeneity of the seafloor. Applying this system, we produced the Global Submarine Landform (GSL) dataset, which divides global submarine landforms into 6 landform zones and 21 landform types. Compared to traditional analysis methods, the GSL dataset achieves global coverage with the highest resolution currently available (15 arc-seconds) and comprehensively reflects large-scale geomorphological features. This dataset can be applied to studies in marine geology, ocean dynamics, and ecosystem research, providing a robust data foundation for understanding seafloor processes and dynamics.

Materials and Methods

Framework of submarine landform driven by terrain knowledge

We identified common terrain characteristics shared by submarine landforms, such as morphological features, spatial relations, and undulating characteristics, and used these as the terrain knowledge for our classification framework. First, we delineated submarine landforms into two zones based on their morphological features: flat landforms and sloped landforms. For flat landforms, we primarily considered their spatial relations, distinguishing three major zones: continental shelves, elevated flat landforms, and plains. For sloped landforms, we focused on their undulating characteristics, further subdividing them into hills, elevated landforms, and depressed landforms. Here, hills represented landforms with relatively low undulation and rugged surfaces, reflecting subtle topographic variations. This method captures the distinct morphological features, spatial relations, and undulating characteristics associated with various submarine landforms, integrating these characteristics as geomorphic knowledge into global-scale automated classification and zoning of seafloor morphology.

Apart from the continental shelf and elevated flat landforms, we further subdivided the seafloor regions. The submarine spatial region was divided into three bathymetric zones: bathyal, abyssal, and hadal, with further refinement of landform types within each zone. Considering the significant differences in undulation between elevated landforms and depressed landforms, we further subdivided these categories into low-relief, mid-relief, and high-relief based on their undulating characteristics. This hierarchical classification approach captures the full spectrum of submarine landform features, from subtle undulations to dramatic bathymetric changes, providing a more comprehensive and detailed representation of seafloor morphology. By integrating bathymetric zones and undulation intensity, our framework ensures a nuanced and systematic classification of submarine landforms, enabling a deeper understanding of their spatial distribution and morphological diversity. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual schematic of the submarine classification system in the framework of this study. For a quantitative description of the above landform types, refer to Supplementary Table S1. The proposed framework categorizes submarine morphology into distinct zonal types, with each type exhibiting homogeneous geomorphic characteristics52.

Conceptual schematic diagram of submarine landform framework in this study. (a) Schematic diagram of submarine landform. Above name represents the six zones of submarine landform (Plains, Elevated flat landform, Shelf, Hills, Elevated landform and Depressed landform). Below name is the corresponding type of flat or sloped landforms. (b) Conceptual framework of submarine landform.

The production of GSL dataset involves five main steps, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Our approach is based on the bathymetric data model. When considering morphological features, we drew inspiration from the concept of distance accumulation and employed cumulative slope analysis to distinguish between flat landforms and sloped landforms53. For flat landforms, we utilized spatial topological adjacency relationships to determine their spatial relations, enabling the identification of continental shelves, elevated flat landforms, and plains. In analysing the undulating characteristics of sloped landforms, we diverged from traditional window-based computational methods. Instead, we constructed the base terrain based on the boundaries between flat and sloped landforms. We calculated the bathymetric relief as the difference between the actual bathymetric values and the base terrain. This approach allowed us to accurately capture the undulating features of sloped landforms and further classify them into low-relief, mid-relief, and high-relief categories.

Bathymetric data and pre-processing

The 15 arc-second GEBCO_2022 grid27 (https://www.gebco.net/data-products/gridded-bathymetry-data/gebco-2022) was used as the source of bathymetric data for global submarine landform classification. The General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO) was dedicated to providing the world’s oceans with the most authoritative, publicly available bathymetry datasets21. Supported by the Seabed 2030 Project, GEBCO has released a 15 arc-second grid bathymetric model of the seafloor, with plans for annual updates to enhance its accuracy and coverage54. The GEBCO_2022 Grid, built upon SRTM15 + V2.4, incorporates predicted depths based on the V31 gravity model and integrates terrestrial topography with measured and estimated bathymetric data.

The GEBCO dataset integrates both terrestrial and submarine topographic data. Prior to processing, a land mask was applied to the dataset, assigning the zero value of bathymetry to all terrestrial areas, thereby generating a global bathymetric model. This approach mitigates potential edge effects caused by land boundary clipping and ensures that regions with zero bathymetric values are classified as continental shelves, aligning with fundamental geomorphological principles55. To enhance computational efficiency and facilitate parallel processing, the global dataset was divided into 16 subregions, each spanning 90° in longitude and 45° in latitude, with each subregion assigned a unique identifier (Fig. 3). During processing, each subregion was expanded by 1° in all four directions to ensure seamless merging of results. To support accurate slope calculation and area measurement, the bathymetric data were projected using the Behrmann projection, an equal-area cylindrical projection that minimizes distortion along the 30° north and south parallels56. For the Arctic region, the North Pole Lambert Azimuthal Equal Area projection was employed.

Data partition and name of global subregions. Each subregion is named based on the latitude line to the south and the longitude line to the west of its extent, with a longitude span of 90° and a latitude span of 45°. For example, s45e90 represents the region with a longitude range between 90°E and 180°E and a latitude range between 45°S and 0°.

Delineation of flat and sloped landforms

Submarine landforms exhibit significant morphological differences, particularly in terms of surface ruggedness and undulation. Various methods have been developed to characterize these topographic variations37,38,39,40. Among these, a terrain metric based on accumulated slope features has proven highly effective in expressing binary topographic differences57,58.

The Accumulated Slope (AS) represents the long-distance relationship of slope gradients between two different locations, capturing the cumulative effect of slope variations across a terrain57. The cost distance calculation is a fundamental spatial analysis technique used to calculate AS. It determines the minimum cumulative cost required to traverse from a given pixel to the nearest source pixel in a raster. This method is widely applied in terrain analysis, pathfinding, and resource allocation studies53,59,60. The core idea is to model the “cost” of moving across a surface, where the cost can represent physical barriers, slope gradients, or other spatially variable factors.

The calculation involves the following key steps:

-

1.

Cost Raster Creation: A cost raster is generated, where each pixel’s value represents the cost of traversing that location. The cost can be derived from various factors, such as slope, elevation, or land cover category.

-

2.

Source Pixel Identification: One or more source pixels are defined as the starting points for the cost distance calculation. These sources represent the locations from which the cumulative cost is computed.

-

3.

Cost Distance Algorithm: The algorithm calculates the minimum cumulative cost from each pixel in the raster to the nearest source pixel. This is achieved by iteratively summing the costs along the least-cost path, considering both the cost of the current pixel and the cumulative cost from adjacent pixels. The AS is calculated as follows:

where a represents the pixel to be calculated, AS(a) represents the Accumulated Slope (AS) at the location of pixel a, D represents the distance between this pixel and its neighboring pixels in a specific direction, Cost(Source) refers to the AS of neighbouring pixels along that direction, and Cost(a) indicates the slope cost value at pixel a.

The initial flat regions for AS calculation were defined based on the assumption that “lower slope indicates a closer affiliation with flat landforms”. Slope derived from DEMs exhibits resolution-dependent uncertainties, where lower-resolution DEMs systematically produce smaller slope for the same terrain61. Since digital bathymetric models generally have coarser resolution than terrestrial elevation models, this necessitates adopting a lower slope threshold for submarine applications compared to terrestrial studies. While terrestrial-based research typically uses thresholds like slope <2° to define flat areas52, we employed slope <0.5° criterion to identify initial flat regions, from which AS was used to delineate complete flat landforms. Grid cells with slopes <0.5° were converted to vector polygons, and those smaller than 10 km2 were excluded to prevent the inclusion of fragmented flat areas within predominantly sloped landforms. Then, with slope used as the cost raster, AS at each grid is calculated on the basis of the principle of distance accumulation53 (Fig. 4).

The results of AS reveal the path with the lowest cumulative cost from the initial flat regions to each cell. Areas with low AS values, on the one hand, reflect their close spatial distance to the initial flat regions, and on the other hand, indicate that the slope along the lowest-cost path from the initial flat regions is gentle, resulting in low cumulative costs to reach these locations. In contrast, areas with high AS values may reflect either their greater spatial distance from the initial flat regions or the presence of high slopes along the lowest-cost path, which act as “barriers,” leading to higher cumulative costs. By integrating topographic slope characteristics with the relationship between slopes at different distances, AS effectively reveals the genetic and morphological homogeneity of the seafloor surface62,63.

Based on the results of AS, flat and sloped landforms are delineated using a threshold-based criterion: areas with AS below the threshold, whose characteristics are closer to those of the initial flat regions, are classified as candidate flat landforms; whereas areas with values above the threshold, exhibiting larger slope accumulation, are classified as candidate sloped landforms. For the same initial flat region, the area delineated as flat landforms varies depending on the threshold applied. A smaller threshold results in a smaller area of candidate flat landforms, while as the threshold increases incrementally, the area of candidate flat landforms also expands gradually. When the threshold is increased by the same increment, the candidate flat landforms area exhibit substantially greater area expansion in relatively flat surrounding terrain, whereas in rugged terrain, the AS values increase rapidly, leading to a smaller expansion of the flat landforms area.

Guided by this principle, a dynamic approach is adopted to determine the optimal threshold. For a specific initial flat region, the threshold is increased at uniform intervals, and the corresponding expansion of the flat landforms area is calculated after each increment. The inflection point in the area expansion is identified as the AS threshold for that initial flat region. Beyond this point, the rate of area expansion diminishes, indicating that the surrounding terrain becomes progressively more rugged. This inflection point thus serves as the critical threshold for distinguishing flat from sloped landforms. In practice, to prevent the indefinite expansion of flat regions, a maximum slope accumulation threshold constraint is necessary. Through preliminary visual assessments across diverse test areas, we identified that thresholds not exceeding 5000 capture the spatial extent of flat landforms. Consequently, this study uses 5000 as the maximum constraint threshold. To enhance computational efficiency, the analysis employs threshold increments of 500 at equal intervals for calculating regional area growth. The results were segmented by eCognition with the segmentation scale of 30. The area and average slope were calculated for the segmented results, and after several iterations, the fragmented patches were eliminated to get a more integrated result (Fig. 5).

Classification of flat landforms

For the further classification of flat landforms, we primarily focus on their spatial relationships. Continental shelves and elevated flat landforms exhibit distinct spatial characteristics, while the remaining flat landforms are classified as plains.

The continental shelf, as a submarine landform adjacent to terrestrial regions, exhibits distinct topographic characteristics64. Unlike most studies that rely solely on a bathymetry threshold of 200 meters to roughly delineate the continental shelf, we incorporated multiple aspects of terrain knowledge to refine its determination. First, the continental shelf typically features a significant slope change at its edge, transitioning from a gentle slope to a steep incline, with the slope break often marking its lower boundary. Second, from a topological perspective, the continental shelf is directly adjacent to landmasses or islands. Third, empirical knowledge suggests that the maximum bathymetry of the continental shelf generally remains around 200 meters. Based on the division of flat landforms and sloped landforms, we utilized the AS to further refine and determine the extent of the continental shelf. The AS calculation originates from the low-water line, which in this study corresponds to the 0-meter contour line, referencing global terrestrial vector boundaries. On the continental shelf, the AS increases gradually due to the gentle slope. However, as the terrain transitions beyond the shelf into the continental slope, the slope steepens sharply, causing the AS value to rise rapidly. We established a classification threshold based on the corresponding AS value, with areas below this threshold identified as part of the continental shelf.

In this study, the elevated flat landform is defined as a flat landform situated on elevated landforms, often surrounded by elevated terrain or located near the top of continental slopes adjacent to continental shelves. Elevated flat landforms are characterized by positive and relatively large bathymetric relief values (definitions of elevated landforms and bathymetric relief will be detailed in the following section). Specifically, a flat landform is classified as a elevated flat landform if its average bathymetric relief exceeds 500 meters or if its average bathymetry value is relatively low (typically less than 2,000 meters). The application of terrain knowledge is crucial in distinguishing elevated flat landforms from other flat landforms, such as continental shelves. While both may exhibit similar surface characteristics, bathymetric zones, and undulation features, their topological relationships differ significantly. Continental shelves are typically adjacent to land or islands, whereas elevated flat landforms are often surrounded by elevated landforms or located near steep continental slopes. This adjacency to elevated terrain or continental slopes serves as a primary criterion for identifying elevated flat landforms.

The plain encompasses all flat landforms other than the continental shelves and elevated flat landforms. Plains are further classified by bathymetric zone: plains at bathymetry of 0–4,000 m are classified as bathyal plains, those at bathymetry of 4,000–6,000 m as abyssal plains, and bathymetry deeper than 6,000 m as hadal plains.

Classification of sloped landforms

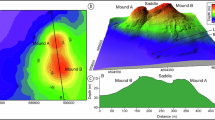

Undulation characteristics are fundamental features that reflect the morphological diversity of submarine landforms. These characteristics play a critical role in distinguishing different zones of sloped landforms, such as hills, elevated landforms, and depressed landforms. Current methods for calculating topographic undulation often rely on window-based analyses, such as the Bathymetric Position Index (BPI) and other similar metrics30,35. However, these window-based approaches have significant limitations that affect their accuracy and reliability.

Firstly, the choice of window size introduces considerable uncertainty into the classification results (Fig. 6a). Different window sizes can cause different relief values, leading to inconsistent interpretations of the same landform. Secondly, window-based analyses typically employ a sliding window approach, which can lead to misleading results due to the incomplete coverage of the entire landform units (Fig. 6b). For example, within an elevated landform, certain areas may exhibit negative relief values (i.e., lower than the average bathymetry of the window), mistakenly classifying them as depressed landforms. Conversely, areas within a depressed landform may show positive relief values (i.e., higher than the average bathymetry of the window), leading to their misclassification as elevated landforms. These inconsistencies arise from the interaction between slope morphology and the position of the sliding window.

Problems of traditional calculation of terrain relief and the improved method in this study. (a) Different window sizes lead to large differences in calculating terrain relief at the same location. (b) Different window positions result in opposite relief in landforms with the similar undulation characteristics. (c) Instead of using window-based analysis, Bathymetric Relief calculated based on base terrain constructed by TIN.

To address these issues, this study adopts a more robust approach by defining a certain boundary for calculating relief. Using the boundaries between flat landforms and sloped landforms as a reference, we establish a base terrain for each sloped landform unit. The base terrain serves as a benchmark for calculating undulation, and the resulting metric is termed Bathymetric Relief (BR). This method aligns with current mainstream geomorphological analyses that focus on terrain units and landform objects, reflecting the semantic characteristics of landforms (Fig. 6c).

Bathymetric Relief (BR) is defined as the difference between the bathymetric value of each grid cell within the boundary of a sloped landform and the corresponding bathymetric value of the grid cell on the base terrain. It is calculated as follows:

where a represents a location of seafloor, BR represents bathymetric relief.

The base terrain is constructed based on the boundaries of the sloped landform using a Triangulated Irregular Network (TIN), which is a digital representation of the surface formed by connecting irregularly spaced points into a network of non-overlapping triangles65,66. The TIN is generated by interpolating the boundary points of the sloped landform, ensuring that the base terrain accurately reflects the overall shape and elevation trends of the landform unit67. By comparing the bathymetric values of each grid cell within the sloped landform to those of the corresponding base terrain, BR effectively captures the undulation characteristics of the landform.

The absolute value of BR represents the magnitude of undulation, while its sign indicates the direction of relief—positive values represent upward convexity (elevated features), and negative values represent downward concavity (depressed features). Specifically, large positive BR values correspond to elevated landforms, such as the geomorphic features of seamounts and mid-ocean ridges. Conversely, large negative BR values correspond to depressed landforms, such as the geomorphic features of trenches and troughs. When the absolute value of BR is close to zero, it indicates a relatively rough surface with minimal undulation, which we classify as hills. These hills represent areas with rugged topography but limited elevation changes. By quantitatively classifying BR based on these criteria, we categorize sloped landforms into three distinct zones: hills, elevated landforms, and depressed landforms.

Extraction of representative landform features

Submarine landforms exhibit considerable variations across different scales, with features of varying scales often overlapping and intermingling without clearly defined boundaries50,68. This complexity presents significant challenges for feature-based geomorphic classification. The classification framework we developed establishes a fundamental spatial architecture for submarine geomorphic distribution. Within this framework, distinct submarine landform features are typically associated with specific types of zoned regions. The zoning and classification system thus provides a critical foundation for the identification and analysis of complex submarine geomorphic elements.

The extraction of submarine landform features from classification results can be accomplished through multiple approaches. The fundamental methodology entails selecting and extracting classification layers that match the target features according to the classification results, subsequently followed by the editing and processing of the extracted layers. Alternatively, a hybrid extraction approach can be utilized, in which relevant classification layers serve as constraint areas and are then integrated with other extraction techniques. Taking seamounts, guyots, plateaus and trenches defined in the IHO standards as examples69, we demonstrated the application of these extraction methods.

For these four types of geomorphological features, we directly extracted them based on the GSL results, using Harris’s GSFM as a reference and excluding some features with indistinct characteristics. During the identification process, we integrated bathymetric data and hillshade visualizations to assist in manual interpretation. Further segmentation was applied to selected features to refine their boundaries.

Since seamounts, guyots and plateaus often exhibit elevated topographic characteristics, we first extracted the elevated landforms, elevated flat landforms, and hills layers and merged them. These were then individually compared with the features of seamounts, guyots and plateaus in the GSFM for identification. Regarding plateaus, since the GSFM plateau dataset was entirely manually digitized, we selected, segmented, and merged regions demonstrating the closest spatial correspondence to derive discrete plateau features.

In contrast, trenches exhibit depressed topographic characteristics and were therefore extracted primarily derived from the classification layers corresponding to depressed landforms. These layers were filtered and segmented by referencing the trench layer from the GSFM dataset, resulting in the final extracted trench dataset.

Data Records

On the basis of the terrain knowledge-based submarine landform framework, the global submarine landform dataset (GSL)70 has been produced. The GSL is stored in a data repository on Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15378203). The final dataset includes major zoning layers, detailed classification layers and feature layers. The dataset comprises two levels of classification: major level and detailed level, corresponding to the zoning and classification results of submarine landforms, respectively. In addition, the dataset includes the representative landform features as the complementary datasets for classification layers. The data is presented in an unsmoothed shapefile format file, and the results can be viewed through ArcGIS Pro. The naming of the data corresponds to the range it contains, as shown in Fig. 3. Loading “LandformStyleLayer.lyrx” as a symbolic layer enables the achievement of the same presentation as that in the figures of this paper.

Major level of classification

At the major level, submarine landforms are divided into two broad categories: flat landform and sloped landform. Building on this, the dataset further partitions the seafloor into six major zones: continental shelf, elevated flat landform, plains, hills, elevated landform, and depressed landform (Fig. 7).

Detailed level of classification

At the detailed level, the classification refines these six zones based on additional criteria. For plains, hills, elevated landforms, and depressed landforms, the dataset incorporates bathymetric zones, dividing them into three bathymetric zones: bathyal, abyssal, and hadal. Additionally, elevated landforms and depressed landforms are further classified based on their bathymetric relief (BR) into three categories: low-relief, mid-relief, and high-relief (Fig. 8).

Global submarine landform classification result with 21 submarine landform types (The detailed level). (a) Global result. (b) Southwest Indian Ridge. (c) Peru–Chile Trench and Nasca Ridge. (d) Mid-Pacific Mountains and Hawaiian Ridge. (e) Mid-Atlantic Ridge. (f) Carlsberg Ridge and Chagos–Laccadive Plateau. (g) Mariana Trench. (h) Mid-Pacific Mountains. (i) Campbell Plateau and Challenger Plateau.

Theoretically, this hierarchical classification framework should have 26 distinct landform types. However, our results include only 21 types due to the absence of certain combinations. The base terrains for bathymetric relief calculations are typically located in the abyssal zone. Consequently, any feature rising above these base terrains would extend into shallower bathymetric zones (abyssal or bathyal), which leads to the absence of elevated landforms in the hadal zone. High-relief elevated landforms are confined to the bathyal zone and absent in the abyssal zone because the bathymetric structure of the deep sea lacks sufficient vertical range to accommodate such features. Additionally, high-relief depressed landforms are absent in the bathyal zone, as significant depressions are more commonly associated with deeper abyssal and hadal zones. These absences are consistent with the natural distribution and formation mechanisms of submarine landforms.

Representative landform features

We have incorporated several extracted layers of representative landform features into the GSL dataset, including a subset of seamounts, guyots, plateaus, and trenches. These features were identified by referring to the corresponding landform features in Harris’s GSFM dataset and complemented by manual interpretation.

Technical Validation

The Global Submarine Landform (GSL) dataset aims to provide a comprehensive and accurate representation of the spatial distribution and morphological diversity of submarine landforms worldwide. To validate the GSL dataset, we conducted assessments from multiple perspectives to ensure its accuracy and usability. The comparison was primarily based on expert interpretation of submarine landform types using seabed topographic data and their derivatives as references, alongside Harris’s Global Seafloor Feature Map (GSFM) as the reference dataset, which is a widely recognized dataset in marine geomorphology44.

First, visual comparison validation was conducted. Taking partial sample areas as examples, the GSL classification layers and representative feature layers were visually compared with those of the GSFM. This allowed for intuitive assessment of spatial consistency and pattern similarity between datasets.

Second, statistical validation of data was performed. We conducted statistical analyses on classification layers across different scales (global and oceanic level) to quantify the area proportions of various landform types and analyse their overall trends. This step ensured the quantitative representativeness of the classification results in reflecting spatial distribution characteristics.

Finally, quantitative validation of comparisons between datasets was implemented. For flat landforms and sloped landforms, assessments were carried out by means of expert visual interpretation of categories at randomly selected points. For the classification layers of major levels, spatial overlay with GSFM base features and partial discrete feature layers was performed to calculate the overlapping area.

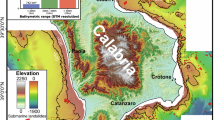

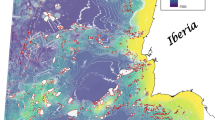

Visual validation through data comparison

Some representative regions were selected for a qualitative comparison between the GSL dataset and the GSFM (Fig. 9), including classification layers and feature layers. The results demonstrate that the GSL dataset captures finer details and more detailed morphological variations in submarine landforms. For instance, the hierarchical classification system used in the GSL dataset effectively reflects bathymetric and undulation characteristics, enabling the representation of diverse landform zones. Additionally, the GSL dataset highlights the continuous spatial transitions and topological structures of submarine landforms. For example, terrain in a given direction may exhibit a gradual transition from plains to hills to elevated landforms, or from plains to hills to depressed landforms, with relief varying from low to high. This reflects the natural gradation of topographic changes and the fuzzy boundaries inherent in submarine landscapes.

The visual comparison of the landform features extracted in this study primarily focuses on the delineated boundaries. In Harris’s work, the extraction of landform features mainly relied on the observation and manual digitization of bathymetric contours generated at intervals of 100 meters. In contrast, the landform features extracted fromthe classification results can be filtered, segmented, and merged to generate relatively objective landform boundaries.

We take the four types of submarine landform features extracted in this study as an illustrative case. Compared with Harris’s results, our classification delineates more refined boundaries for these landform features (Fig. 10). These detailed boundaries can effectively guide the extraction of landform features with higher precision.

For the hybrid extraction scheme, our classification results can also serve as spatial constraints for identifying relevant landform features. Taking submarine canyons as an example, statistical analysis shows that more than 93.4% of the canyon area in the GSFM dataset is located within sloped landforms. By first extracting submarine canyons confined to sloped landforms and then applying further processing steps, it becomes possible to eliminate unrepresentative canyon features derived from flat areas, while also reducing the amount of interpretation and manual editing required.

Statistical assessment of landform compositions

The global seafloor exhibits a rich diversity of submarine landforms, broadly categorized into flat landforms and sloped landforms, which occupy nearly equal proportions of the seabed (Table 1). This distribution of proportions reflects the more complex and diverse characteristics of the seafloor, rather than being dominated by flat terrains primarily shaped by sedimentary processes71. Plains are the most widespread among flat landforms, while hills dominate sloped terrains, consistent with the general understanding of seafloor morphology4. Elevated landforms and continental shelves have comparable proportions, whereas depressed landforms and elevated flat landforms are relatively rare. While seamounts and ridges are widely distributed across the ocean floor, a significant portion of these features exhibit relatively modest relief. As a result, the area occupied by elevated landforms with large relief is smaller compared to that with smaller undulations. Similarly, depressed landforms, such as trenches and troughs, though spanning considerable bathymetric ranges, are concentrated in specific regions, leading to their limited overall spatial coverage. The statistical results are generally consistent with Harris’s GSFM in terms of trends, particularly for the continental shelf corresponding to the GSFM, where the difference in total area proportion is less than 0.1%.

At the oceanic scale, the composition of submarine landforms varies significantly across different ocean basins. We analysed seven oceanic regions: the North Pacific, South Pacific, North Atlantic, South Atlantic, Indian Ocean, Arctic Ocean, and Southern Ocean (defined as the region south of 60°S). In the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans, the proportions of flat and sloped landforms are relatively consistent (Fig. 11a). However, the North Pacific and North Atlantic have slightly larger proportions of flat landforms compared to their southern parts. The Southern Ocean and Arctic Ocean exhibit a higher prevalence of flat landforms, with the Arctic Ocean having the highest proportion (86.6%), likely due to its extensive ice cover and shallow continental shelves72.

In terms of the six landform zones, most oceans follow global trends in landform composition, with the exception of the Arctic Ocean (Fig. 11b). The Arctic Ocean is unique, with over half of its area covered by continental shelves, a stark contrast to other oceans. The North Atlantic displays a more balanced composition of landforms, with lower proportions of plains and hills but higher proportions of elevated landforms, depressed landforms, and elevated flat landforms compared to other regions. The Southern Ocean has the highest proportion of plains (51.7%), while the North Atlantic and Arctic Ocean have plains covering less than 40% of their seabed. Hills are most prevalent in the South Pacific and South Atlantic, each exceeding 35%, whereas the Arctic Ocean has a minimal hills area (3.1%). Continental shelves are most extensive in the Arctic Ocean, followed by the North Atlantic and Southern Ocean, each exceeding 10%. In contrast, the South Pacific and South Atlantic have continental shelf proportions below 5%. Elevated landforms are most prominent in the Indian Ocean, North Atlantic, and North Pacific, all exceeding the global average. Depressed landforms are most common in the Atlantic Ocean, while being least represented in the Southern Ocean and Arctic Ocean.

Quantitative validation through data comparison

Validation of flat and sloped landforms

The validation of flat and sloped landforms is conducted using randomly sampled points across the global ocean. This approach leverages the bathymetric model, slope, and hillshade map to assess the consistency between the interpreted morphological features and the GSL classification results (flat or sloped landforms). Hillshade, which simulates the illumination of the seafloor surface, is particularly useful for identifying subtle topographic variations and enhancing the visual distinction of landform types73.

We generated 36,000 random points distributed uniformly across the global ocean. For each point, we visually interpreted its morphological feature using a combination of bathymetric data, slope, and hillshade maps. The interpretation focused on distinguishing between flat landforms and sloped landforms. The interpreted results were then compared with the corresponding classifications in the GSL dataset to evaluate the consistency and accuracy of the automated classification framework.

To quantify the performance of the GSL dataset, we calculated four key metrics: precision, recall, accuracy, and F1 score. These metrics are defined as follows:

Precision: The proportion of correctly classified flat or sloped landforms among all landforms identified as such by the GSL dataset.

Recall: The proportion of correctly classified flat or sloped landforms among all landforms that should have been identified as such.

Accuracy: The proportion of correctly classified points (both flat and sloped) among all points.

F1 Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced measure of the dataset’s performance.

In the evaluation metrics, TP refers to the cases where the GSL dataset correctly identifies a landform as either flat or sloped. FP refers to the cases when the GSL dataset incorrectly identifies a landform as flat or sloped when it is not. TN refers to the cases where the GSL dataset correctly identifies a landform as not being flat or sloped. FN refers to the cases where the GSL dataset fails to identify a landform as flat or sloped when it should have.

These results highlight the GSL dataset’s reliability in distinguishing between flat and sloped landforms (Table 2). The slightly lower precision for sloped landforms may be attributed to the inherent complexity of steep terrains, which often exhibit highly variable and irregular surface features. Additionally, the morphological diversity within sloped landforms, such as the presence of both elevated and depressed features within a single unit, further complicates the identification process. Overall, the high accuracy indicate that the dataset performs well in minimizing false negatives, ensuring that most true landforms are correctly identified.

Validation of classification layers

To further validate the accuracy and reliability of the GSL classification layers, we conducted a comparative analysis with the GSFM, which provides a comprehensive representation of submarine landforms and serves as a reference for evaluating the our dataset.

Due to differences in the classification frameworks between the GSL dataset and the GSFM, a direct quantitative comparison is not feasible. Instead, we conducted an overlay analysis using the GSFM’s two primary layers—base layers and feature layers—to assess the consistency and precision of the GSL dataset.

The comparison with the GSFM base layers includes continental shelves, slopes, abyssal plains (with subcategories such as plains, hills, and mountains derived from window-based relief analysis), and hadal zones. For continental shelves, a direct overlay comparison was performed, and the results revealed high accuracy, as reflected in the precision and recall values shown in Table 3. Minor differences were primarily attributed to differences in data resolution and methodological approaches.

For other landform zones, we conducted an overlay analysis between the GSFM categories and the six landform zones in the GSL dataset (Fig. 12a). The comparison revealed significant correlations between specific landform categories in the GSFM and the GSL dataset, with high overlap proportions. In the GSFM’s abyssal zone, plains, hills, and mountains showed significant overlap with the GSL dataset’s plains (88.8%), hills (44.6%), and elevated landforms (38.7%), respectively. In the hadal zone, GSFM landforms predominantly overlapped with GSL’s depressed landforms (39.9%). These high overlap proportions demonstrate strong consistency between the two datasets, despite differences in classification methods and resolution. As the composite geomorphic features located at continental margins, most continental slopes in the GSL dataset were classified as elevated landforms, with the remaining portions categorized as elevated flat landforms (flat terrain at the top of continental slopes) and hills (terrain at the base of continental slopes). This reflects the elevated nature of continental slopes within the seafloor.

The window-based analysis used in the GSFM tended to overestimate the proportions of hills and mountains. For example, 47.4% of the GSFM hills corresponded to plains in the GSL dataset, while only 44.6% matched the GSL hills. Similarly, 45.3% of the GSFM mountains aligned with hills in the GSL dataset, and 38.7% corresponded to elevated landforms. These discrepancies highlight the structural differences between the two classification systems.

For the feature-based comparison, we selected 12 landform types from the GSFM and overlaid them with the six major zones in the GSL dataset (Fig. 12b). Fans and ridges are predominantly found in plains, reflecting their association with flat or gently sloping terrains. Spreading ridges show a relatively even distribution, with nearly half located in hills, highlighting their transitional nature between flat and elevated terrains. More than half of the ridges, guyots, escarpments, seamounts, and canyons are distributed in elevated landforms, consistent with their characteristic steep and prominent topographic features. Over 70% of trenches are located in depressed landforms, aligning with their deep, concave morphology. These distribution patterns demonstrate that the GSL dataset accurately captures the spatial characteristics of submarine landforms, as evidenced by its consistency with the GSFM’s feature-based classifications. The results reflect an alignment with known submarine geomorphological distribution trends, further validating the reliability and precision of the GSL dataset.

Usage Notes

Diverging from conventional classification of submarine landforms, the GSL introduces a novel perspective in submarine landform, offering a fresh cognitive approach to understanding seafloor features. This classification approach effectively captures the diverse and complex morphological features of seafloor terrain. It has the potential to be applied in other marine fields, aiding in an improved understanding of ocean processes. The terrain knowledge-driven framework for submarine landform research proposed in this study can also be applied to regional-scale studies and offers valuable insights for submarine geomorphology research. The methods and framework presented here are adaptable to high-resolution local bathymetric data and can be applied to submarine landform studies at various scales.

Users are encouraged to utilize our dataset as a base map for visualizing and analysing submarine landforms, which can provide a reliable foundation for representing the diversity of seafloor morphology. For the extraction of submarine landform features, the method developed in this study, which extracts four types of landform elements directly from the classification layers, provides a feasible solution. In addition, we encourage users to integrate specialized extraction techniques for specific submarine landform types with our classification results, applying hybrid extraction schemes to further refine results according to particular research objectives.

The dataset is also well-suited for conducting more in-depth research on the spatial distribution and landscape characteristics of submarine landforms, which will provide a comprehensive framework for exploring their geomorphic features and patterns. Additionally, we encourage integrating this dataset with other marine datasets to facilitate interdisciplinary research across various fields, such as marine geology, biodiversity, and ocean dynamics.

Code availability

The procedures in this study are completed via ArcGIS Pro, Python with arcPy and eCognition. The code based on python with arcpy has been uploaded into Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1537820370) along with the data, and the execution of this code requires the support of the arcpy environment.

References

Ronov, A. B. Phanerozoic transgressions and regressions on the continents; a quantitative approach based on areas flooded by the sea and areas of marine and continental deposition. American Journal of Science 294, 777–801 (1994).

Batchelor, C. L., Dowdeswell, J. A. & Rignot, E. Submarine landforms reveal varying rates and styles of deglaciation in North-West Greenland fjords. Marine Geology 402, 60–80 (2018).

Hillier, J. K. Submarine Geomorphology: Quantitative Methods Illustrated with the Hawaiian Volcanoes. in Developments in Earth Surface Processes vol.15, 359–375 (Elsevier, 2011).

Submarine Geomorphology. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57852-1 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2018).

Sobolev, S. V. & Brown, M. Surface erosion events controlled the evolution of plate tectonics on Earth. Nature 570, 52–57 (2019).

Naranjo-Vesga, J. et al. Controls on submarine canyon morphology along a convergent tectonic margin. The Southern Caribbean of Colombia. Marine and Petroleum Geology 137, 105493 (2022).

Gille, S. T., Metzger, E. J. & Tokmakian, R. Seafloor Topography and Ocean Circulation | Oceanography. (2004).

Kunze, E. & Smith, S. G. L. The Role of Small-Scale Topography in Turbulent Mixing of the Global Ocean | Oceanography. (2004).

Escobar-Briones, E. G., Gaytán-Caballero, A. & Legendre, P. Epibenthic megacrustaceans from the continental margin, slope and abyssal plain of the Southwestern Gulf of Mexico: Factors responsible for variability in species composition and diversity. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 55, 2667–2678 (2008).

Streuff, K., Ó Cofaigh, C., Noormets, R. & Lloyd, J. Submarine landform assemblages and sedimentary processes in front of Spitsbergen tidewater glaciers. Marine Geology 402, 209–227 (2018).

Zhang, K. et al. Complex tsunamigenic near-trench seafloor deformation during the 2011 Tohoku–Oki earthquake. Nat Commun 14, 3260 (2023).

Madricardo, F. et al. High resolution multibeam and hydrodynamic datasets of tidal channels and inlets of the Venice Lagoon. Sci Data 4, 170121 (2017).

Hasterok, D. et al. New Maps of Global Geological Provinces and Tectonic Plates. Earth-Science Reviews 231, 104069 (2022).

Oetting, A. et al. Geomorphology and shallow sub-sea-floor structures underneath the Ekström Ice Shelf, Antarctica. The Cryosphere 16, 2051–2066 (2022).

Minár, J. & Evans, I. S. Elementary forms for land surface segmentation: The theoretical basis of terrain analysis and geomorphological mapping. Geomorphology 95, 236–259 (2008).

Bishop, M. P., James, L. A., Shroder, J. F. & Walsh, S. J. Geospatial technologies and digital geomorphological mapping: Concepts, issues and research. Geomorphology 137, 5–26 (2012).

Dowdeswell, J. A. et al. The variety and distribution of submarine glacial landforms and implications for ice-sheet reconstruction. Memoirs 46, 519–552 (2016).

Ismail, K., Huvenne, V. & Robert, K. Quantifying spatial heterogeneity in submarine canyons. Progress in Oceanography 169, 181–198 (2018).

Smith, W. H. F. & Sandwell, D. T. Global Sea Floor Topography from Satellite Altimetry and Ship Depth Soundings. Science 277, 1956–1962 (1997).

Becker, J. J. et al. Global Bathymetry and Elevation Data at 30 Arc Seconds Resolution: SRTM30_PLUS. Marine Geodesy 32, 355–371 (2009).

Weatherall, P. et al. A new digital bathymetric model of the world’s oceans. Earth and Space Science 2, 331–345 (2015).

Dorschel, B. et al. The International Bathymetric Chart of the Southern Ocean Version 2. Sci Data 9, 275 (2022).

Dandabathula, G. et al. A High-Resolution Digital Bathymetric Elevation Model Derived from ICESat-2 for Adam’s Bridge. Sci Data 11, 705 (2024).

Jakobsson, M. et al. The International Bathymetric Chart of the Arctic Ocean Version 5.0. Sci Data 11, 1420 (2024).

Tozer, B. et al. Global Bathymetry and Topography at 15 Arc Sec: SRTM15+. Earth and Space Science 6, 1847–1864 (2019).

Ruan, X. et al. A new digital bathymetric model of the South China Sea based on the subregional fusion of seven global seafloor topography products. Geomorphology 370, 107403 (2020).

GEBCO Compilation Group GEBCO_2022 Grid (https://doi.org/10.5285/e0f0bb80-ab44-2739-e053-6c86abc0289c) (2022).

MacFerrin, M., Amante, C., Carignan, K., Love, M. & Lim, E. The Earth Topography 2022 (ETOPO 2022) Global DEM dataset. Earth System Science Data Discussions 1–24 https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-2024-250 (2024).

Lecours, V., Dolan, M. F. J., Micallef, A. & Lucieer, V. L. A review of marine geomorphometry, the quantitative study of the seafloor. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 20, 3207–3244 (2016).

Erdey-Heydorn, M. D. An ArcGIS Seabed Characterization Toolbox Developed for Investigating Benthic Habitats. Marine Geodesy 31, 318–358 (2008).

Lundblad, E. R. et al. A Benthic Terrain Classification Scheme for American Samoa. Marine Geodesy 29, 89–111 (2006).

Hillier, J. K., Tilmann, F. & Hovius, N. Editorial Submarine geomorphology: new views on an ‘unseen’ landscape. Basin Research 20, 467–472 (2008).

Du Preez, C. A new arc–chord ratio (ACR) rugosity index for quantifying three-dimensional landscape structural complexity. Landscape Ecol 30, 181–192 (2015).

Jerosch, K., Kuhn, G., Krajnik, I., Scharf, F. K. & Dorschel, B. A geomorphological seabed classification for the Weddell Sea, Antarctica. Mar Geophys Res 37, 127–141 (2016).

Walbridge, S., Slocum, N., Pobuda, M. & Wright, D. Unified Geomorphological Analysis Workflows with Benthic Terrain Modeler. Geosciences 8, 94 (2018).

Arosio, R. et al. CoMMa: A GIS geomorphometry toolbox to map and measure confined landforms. Geomorphology 458, 109227 (2024).

Wilson, M. F. J., O’Connell, B., Brown, C., Guinan, J. C. & Grehan, A. J. Multiscale Terrain Analysis of Multibeam Bathymetry Data for Habitat Mapping on the Continental Slope. Marine Geodesy 30, 3–35 (2007).

Brown, C. J., Smith, S. J., Lawton, P. & Anderson, J. T. Benthic habitat mapping: A review of progress towards improved understanding of the spatial ecology of the seafloor using acoustic techniques. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 92, 502–520 (2011).

Fan, M. et al. High resolution geomorphological classification of benthic structure on the Western Pacific Seamount. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 1007032 (2022).

Harris, P. T. & Whiteway, T. Global distribution of large submarine canyons: Geomorphic differences between active and passive continental margins. Marine Geology 285, 69–86 (2011).

Kim, S.-S. & Wessel, P. New global seamount census from altimetry-derived gravity data: New global seamount census. Geophysical Journal International 186, 615–631 (2011).

Gevorgian, J., Sandwell, D. T., Yu, Y., Kim, S.-S. & Wessel, P. Global Distribution and Morphology of Small Seamounts. Earth and Space Science 10, e2022EA002331 (2023).

Shi, S. & Richardson, M. An improved method for semi-automated identification of submarine canyons and sea channels using digital bathymetric analysis. Marine Geology 474, 107339 (2024).

Harris, P. T., Macmillan-Lawler, M., Rupp, J. & Baker, E. K. Geomorphology of the oceans. Marine Geology 352, 4–24 (2014).

Guilbert, E. & Moulin, B. Towards a Common Framework for the Identification of Landforms on Terrain Models. IJGI 6, 12 (2017).

Xiong, L., Tang, G., Yang, X. & Li, F. Geomorphology-oriented digital terrain analysis: Progress and perspectives. J. Geogr. Sci. 31, 456–476 (2021).

Li, S. et al. Integrating topographic knowledge into deep learning for the void-filling of digital elevation models. Remote Sensing of Environment 269 (2022).

Martha, T. R., Kerle, N., van Westen, C. J., Jetten, V. & Kumar, K. V. Segment Optimization and Data-Driven Thresholding for Knowledge-Based Landslide Detection by Object-Based Image Analysis. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 49, 4928–4943 (2011).

Chen, J., Xiong, L., Yin, B., Hu, G. & Tang, G. Integrating topographic knowledge into point cloud simplification for terrain modelling. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 37, 988–1008 (2023).

Dove, D. et al. A Two-Part Seabed Geomorphology Classification Scheme (v.2); Part 1: Morphology Features Glossary. https://zenodo.org/record/4075248 (2020).

Nanson, R. et al. A Two-Part Seabed Geomorphology Classification Scheme; Part 2: Geomorphology Classification Framework and Glossary (Version 1.0). https://zenodo.org/record/7804019 (2023).

Drăguţ, L. & Blaschke, T. Automated classification of landform elements using object-based image analysis. Geomorphology 81, 330–344 (2006).

Douglas, D. H. Least-cost Path in GIS Using an Accumulated Cost Surface and Slopelines. Cartographica 31, 37–51 (1994).

Mayer, L. et al. The Nippon Foundation—GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project: The Quest to See the World’s Oceans Completely Mapped by 2030. Geosciences 8, 63 (2018).

Xie, P., Liu, Y., He, Q., Zhao, X. & Yang, J. An Efficient Vector-Raster Overlay Algorithm for High-Accuracy and High-Efficiency Surface Area Calculations of Irregularly Shaped Land Use Patches. IJGI 6, 156 (2017).

Lapaine, M. Behrmann Projection. in 7th International Conference on Cartography and Gis, Vols 1 and 2 (eds Bandrova, T. & Konecny, M.) 226–235 (Bulgarian Cartographic Assoc, Sofia, 2018).

Li, S., Yang, X., Zhou, X. & Tang, G. Quantification of Surface Pattern Based on the Binary Terrain Structure in Mountainous Areas. Remote Sensing 15, 2664 (2023).

Li, S. et al. A multilevel dataset of landform mapping and geomorphologic descriptors for the Loess Plateau of China. Sci. Data 11, 1282 (2024).

Verbeylen, G., De Bruyn, L., Adriaensen, F. & Matthysen, E. Does matrix resistance influence Red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris L. 1758) distribution in an urban landscape? Landscape Ecology 18, 791–805 (2003).

Chen, Y., She, J., Li, X., Zhang, S. & Tan, J. Accurate and Efficient Calculation of Three-Dimensional Cost Distance. IJGI 9, 353 (2020).

Tang, G., Zhao, M., Li, T., Liu, Y. & Xie, Y. Modeling Slope Uncertainty Derived from DEMs in Loess Plateau. Acta Geographica Sinica 58, 824–830 (2003).

Fonseca, F., Egenhofer, M., Davis, C. & Câmara, G. Semantic Granularity in Ontology-Driven Geographic Information Systems.

Xiong, L., Li, S., Tang, G. & Strobl, J. Geomorphometry and terrain analysis: data, methods, platforms and applications. Earth-Science Reviews 233 (2022).

Stewart, H. A., Bradwell, T., Carter, G. D. O., Dove, D. & Gafeira, J. Geomorphology of the Continental Shelf. in Landscapes and Landforms of Scotland (eds. Ballantyne, C. K. & Gordon, J. E.) 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71246-4_6 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2021).

Yang, B., Shi, W. & Li, Q. An integrated TIN and Grid method for constructing multi-resolution digital terrain models. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 19, 1019–1038 (2005).

Hu, G. et al. Using vertices of a triangular irregular network to calculate slope and aspect. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 36, 382–404 (2022).

Peng, Q. & Zheng, X. Research on Digital Elevation Model Construction Method Based on TIN. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 1237, 022174 (2019).

Huang, Z. et al. Rule-based semi-automated tools for mapping seabed morphology from bathymetry data. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1236788 (2023).

International Hydrographic Organization, 2019. Standardization of Undersea Feature Names Guidelines Proposal Form Terminology Edition 4.2.0. Online publication. Retrieved at: https://iho.int/uploads/user/pubs/bathy/B-6_e4%202%200_2019_EF_clean_3Oct2019.pdf (2019).

Yu, F. et al. Global submarine landform dataset. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15378203 (2025).

Blondel, P. Bathymetry and Its Applications. https://doi.org/10.5772/2132 (2012).

Jakobsson, M. Submarine glacial landform distribution in the central Arctic Ocean shelf–slope–basin system. Memoirs 46, 469–476 (2016).

Van Den Eeckhaut, M. et al. The effectiveness of hillshade maps and expert knowledge in mapping old deep-seated landslides. Geomorphology 67, 351–363 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number: No. 42371407], the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions and the Deep-time Digital Earth (DDE) Big Science Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.Y., L.X. and G.T. conceived and designed the study; F.Y. and L.X. performed the experiment and analysis; F.Y. and L.X. wrote the first version of the manuscript. H.W. and J.S. coordinated the work and reviewed the manuscript. H.W. and G.T. assisted with quality control and reviewed the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, F., Xiong, L., Wang, H. et al. A global scale submarine landform dataset driven by terrain knowledge. Sci Data 12, 870 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05264-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05264-6