Abstract

Diatoms, a major group of microalgae, play a critical role in global carbon cycling and primary production. Despite their ecological significance, comprehensive genomic resources for diatoms are limited. To address this, we have annotated previously unannotated genome assemblies of 49 diatom species. Genome assemblies were obtained from NCBI Datasets and processed for repeat elements using RepeatModeler2 and RepeatMasker. For gene prediction, BRAKER2 was employed in the absence of transcriptomic data, while BRAKER3 was utilised when transcriptome short read data were available from the Sequence Read Archive. The quality of genome assemblies and predicted protein sets was evaluated using BUSCO, ensuring high-quality genomic resources. Functional annotation was performed using EnTAP, providing insights into the biological roles of the predicted proteins. Our study enhances the genomic toolkit available for diatoms, facilitating future research in diatom biology, ecology, and evolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Diatoms are a diverse group of algae that significantly contribute to global carbon fixation and marine and freshwater ecosystem function1. In addition to their ecological role, their ability to tolerate and quickly acclimate to rapidly changing environmental conditions is remarkable2. These photosynthetic microalgae may capture and transmit \({{CO}}_{2}\) into diverse compounds, including lipids, omega-3 fatty acids, pigments, antioxidants, and polysaccharides3. They produce a variety of phytosterols, which offer possible health benefits such as cholesterol-lowering properties4. Diatoms can be cultivated indoors and outdoors, and their biomass productivity can be doubled in high-technology photobioreactors. A few selected species are used as model organisms in genetics and biochemistry research, while several taxa could be a bioprocess platform for biofuels3.

Diatoms play a critical role in the global carbon cycle3,5,6. Through photosynthesis, diatoms convert carbon dioxide into organic carbon, forming the basis of marine food webs and assisting in the sequestration of carbon in ocean sediments6. Diatoms fix atmospheric carbon dioxide, accounting for around 20% of the world’s primary production7. Their silica-based cell walls contribute to long-term carbon storage as they cause diatom cells to sink and settle on the ocean floor or the bottom of lakes and rivers. This process may be especially important during diatom blooms, which characterise temperate ocean margin zones and freshwater bodies in the spring. Various environmental factors in interactions with marine ecosystems affect the onset and progression of blooms, such as temperature, light intensity, and fluctuations of nutrients8,9.

Interaction and coexistence with bacterial communities are an integral part of the life of diatom algae. They also form consortia and heterogeneous cohorts building networks of numerous cell-to-cell interactions for e.g. nutrient exchange. In this mutually beneficial deal, bacteria contribute by assimilating nutrients from the water and sequester minerals released by diatoms efficiently. Further, bacteria supply nutrients that diatoms are not able to produce themselves, for example, vitamins and fixed nitrogen10. Additionally, diatom blooms influence bacterial communities, showcasing their interconnectedness in marine ecosystems (e.g.11,12,13. At the same time, bacteria impact the dynamics of diatom growth14. The ecological roles of diatoms and their interaction with other organisms are now better-understood thanks to molecular techniques, which have provided new insights into cell death, silicon metabolism, environmental sensing, and community-level interactions15.

However, despite the frequency and importance of diatoms in the ecosystem, complete genetic resources for diatoms are scarce. When starting this study, we found 89 Bacillariophyta genome assemblies at National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Datasets (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/, April 1st, 2024, see Supplementary Table S1). Of these, 66 were flagged as “representative genomes”. In total, 13 of these genome assemblies had an annotation of protein coding genes, but only seven of the genome assemblies flagged as “representative genomes” had such an annotation. This means for four of the annotated assemblies, a younger and better but yet unannotated genome assembly existed (but the assembly of Thalassiosira pseudonana was not flagged as representative, had been annotated, and no alternative representative genome assembly was available). For three species available at the NCBI, we found an annotation of protein coding genes in PhycoCosm16 but not at the NCBI. Knowledge about the protein coding genes is essential to fully exploit genome sequences17, and thus we made it our mission to annotate previously unannotated genome assemblies of the Bacillariophyta.

Initially, we set out to annotate the genome assemblies of all Bacillariophyta that did not have an annotation of protein coding genes, or where a younger and better representative genome has been made available without annotation. Looking at redundancy (sometimes more than one genome assembly for the same species is available), we selected one assembly from each species. However, we decided later to exclude 10 genome assemblies (see Supplementary Table S2), either due to technical problems during download or annotation, or due to data quality. We ended up successfully annotating 49 Bacillariophyta genome assemblies18 (references to the original sequence data publications are listed in Table 1, genome assembly details are given in Supplementary Table S3, a taxonomic tree is shown in Fig. 1).

Taxonomy tree of selected Bacillariophyta genomes. This tree displays species of selected Bacillariophyta genome assemblies available from NCBI datasets between June 14th and 26th 2024. The tree was generated by PhyloT (https://phylot.biobyte.de/, August 21st 2024), visualised with iTol57. Species with representative genome assemblies with a previously existing annotation at NCBI are labelled in grey. Genomes that we annotated are colored in different shades of blue. From lightest to darkest blue: with BRAKER3; with BRAKER3 including proteins from the same species that were already available for an older assembly at NCBI or from PhycoCosm; with BRAKER2; with BRAKER2 including proteins from the same species that were already available for an older assembly at NCBI or from PhycoCosm. We excluded “uncultured” entries and those matching only two letters followed by a dot, e.g. “sp.”.

With this study, we present the annotation data of protein coding genes for 49 Bacillariophyta genome assemblies that were previously stored as unannotated at NCBI Datasets. Combined with the previously existing annotations, this now makes a total of 58 Bacillariophyta genome annotations accessible for further studies (Fig. 2 visualises how these 58 species cover the taxonomic clades of Bacillariophyta). Together, these data can be applied to various scientific problems and help researchers better understand many of the processes in diatom algae.

Stacked bar plot showing the distribution of species with structurally annotated genomes (9 previously annotated, 49 newly annotated in this study) across taxonomic subclades of Bacillariophyta. The lower portion of each bar represents species with annotated genomes, while the full bar height represents the total number of known species according to NCBI Taxonomy.

Methods

The genome annotations presented here were generated using publicly available genome, transcriptome, and protein data. Data analysis was performed in three steps: (1) data preparation, (2) structural genome annotation, and (3) functional genome annotation. After annotation, we performed assembly contamination analysis (4) and identified horizontal gene transfer candidates (5). Steps 1 and 2 were executed using a semi-automated and reproducible Snakemake workflow19 that is publicly available at https://github.com/KatharinaHoff/braker-snake (August 30th, 2024). Singularity20 was employed to manage software dependencies. Steps 3–5 were performed manually. In addition to genome annotation, we also estimated ploidy in a large number of genome assemblies. All software version numbers are listed in Supplementary Table S4.

Data preparation

In short, we used the NCBI Datasets tool to retrieve Bacillariophyta genome assembly information from the NCBI database (in this case available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/ via web browser). Assembly information was filtered to exclude ‘uncultured’ samples and species names ending in ‘sp.’ If multiple assemblies were available for the same species, we prioritized the ‘representative’ assembly, or, if unavailable, the assembly with the largest N50. Genomes with fewer than or equal to 1,000 annotated proteins were selected as candidates for further annotation. This threshold was set to include genome assemblies for annotation that have only a protein coding gene annotation for organelle genomes. For each candidate genome, we checked if an older assembly had existing protein-coding gene annotations (referred to as ‘legacy proteins’) and stored this information. All genome assemblies and any associated legacy proteins were downloaded using the datasets tool.

The workflow automatically retrieves the appropriate OrthoDB v11 partition21 for the specified taxon from https://bioinf.uni-greifswald.de/bioinf/partitioned_odb11/ (in the case of diatoms, that is a combination of the following two files: https://bioinf.uni-greifswald.de/bioinf/partitioned_odb11/Stramenopiles.fa.gz and https://bioinf.uni-greifswald.de/bioinf/partitioned_odb11/Viridiplantae.fa.gz). For Bacillariophyta, this corresponds to the Stramenopiles partition, which we combined with the Viridiplantae partition to ensure a larger sequence set.

For species lacking genome annotations, RNA-seq data availability was verified using the Biopython/Entrez API to query the Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra)22. Up to six Illumina paired-end libraries were selected (the top six entries from the Entrez results), and downloaded using fasterq-dump (https://trace.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra/sra.cgi?view=software, accessed August 21st, 2024). RNA-seq data were aligned to the genome using HISAT223. Co-culture libraries were not excluded, as they often provide critical data for diatoms, but libraries with an alignment rate below 20% were discarded. The resulting SAM files were converted to BAM, merged if multiple files existed, sorted, and indexed using SAMtools24.

Before proceeding with automated annotation, we manually queried the PhycoCosm portal (Joint Genome Institute) for existing protein-coding gene annotations for species in our dataset. For Cyclotella cryptica25,26, Nitzschia putrida27 and Pseudo-nitzschia multiseries, we downloaded available protein sequences and included them as ‘legacy proteins’ in the BRAKER annotation process.

The final output of this data preparation phase was a CSV file that specifies the input files required for the subsequent annotation workflow for each species.

Structural genome annotation

Each selected genome assembly was processed individually using a consistent pipeline. First, RepeatModeler228 was used to construct a species-specific repeat library, followed by RepeatMasker (http://www.repeatmasker.org, accessed August 21st, 2024) to soft mask the repeats in the genome. Depending on the availability of extrinsic data, either BRAKER2 or BRAKER329,30 was employed to predict protein-coding gene structures from the soft-masked genome.

Protein evidence was always used during annotation. For many genomes, the combined Stramenopiles/Viridiplantae protein partition was used as input. Additionally, legacy proteins were incorporated when available. In cases where RNA-seq data were absent, BRAKER2 was run with an option to enrich the predicted gene set using BUSCOs from the Stramenopiles_odb10 dataset31, enhanced with compleasm32. BRAKER2 first uses GeneMark-EP + 33, which self-trains GeneMark-ES34,35 to identify seed gene sequences. These sequences are then compared to the protein database using DIAMOND36, followed by accurate spliced alignment with Spaln237. GeneMark-EP + generates an intermediate gene set based on protein evidence, which is refined using AUGUSTUS38,39. TSEBRA40 then combines and filters the predictions using protein evidence and BUSCOs as guides41.

When RNA-seq alignments were available, BRAKER3 was used. This workflow employed GeneMark-ETP42, which processes RNA-seq alignments using StringTie243 to assemble transcripts. GeneMarkS-T44 then screens the assembled transcripts for potential genes. DIAMOND and GeneMark-EP + ‘s protein evidence pipeline were used to filter the genes, and GeneMark-ETP also performed initial gene predictions based on self-training. AUGUSTUS was again trained on a reliable subset of predicted genes, and the final gene set was merged using TSEBRA.

Not all BRAKER jobs completed successfully; assemblies affected by these failures were excluded from further analysis (see Supplementary Table S2).

For quality control, we ran BUSCO with the stramenopiles_odb10 dataset on both the genome assemblies and the predicted protein sequences. Genomes were excluded if there was a significant discrepancy between BUSCO completeness scores at the genome level and the predicted protein level. For example, despite a 95% BUSCO completeness score at the genome level, Pseudo-nitzschia delicatissima achieved only 72% completeness at the annotation level and was excluded (see Fig. 3). Additionally, Thalassiosira sundarbana was excluded due to low genome BUSCO completeness (15%) and contamination in the database. Epithemia catenata was also excluded due to low genome BUSCO completeness (56%).

Rooted species tree of Bacillariophyta with an annotation of protein coding genes. Major diatom lineages are labelled on the right. The previously annotated species (C. tenuissimus, C. closterium, F. crotonensis, M. pseudoterrestris, N. inconspicua, P. tricornutum, Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata, S. robusta, and T. pseudonana) are labeled with a star. The numbers displayed on branches correspond to support values according to the Shimodaira-Hasegawa-like method242.

Functional gene annotation

The EnTAP functional annotation software was employed to provide functional descriptors and identify potential contaminants for the predicted proteins45. EnTAP was configured with two curated databases, NCBI’s RefSeq Protein46 and UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot47, for similarity searches, utilising a 50% target and query coverage minimum, and a DIAMOND E-value threshold of 0.00001. An optimal alignment was selected for each protein query based on phylogenetic relevance, informativeness, and standard alignment quality metrics. Additionally, EnTAP performed independent searches against the EggNOG database48 using the EggNOG-mapper toolbox49. The resulting gene family assignments, along with high-quality similarity search alignments, facilitated the subsequent connections to Gene Ontology terms50,51, protein domains from Pfam52, and pathway associations via KEGG53.

Contamination and HGT analysis

We screened each assembly for potential contamination by leveraging the EnTAP classification of individual transcripts as either contaminated or uncontaminated. In EnTAP, contaminant transcripts aligned with high confidence to the NCBI RefSeq microbial database or exclusively to the microbial gene families housed in EggNOG. Annotated transcripts in each assembly were mapped back to their corresponding contigs, and the proportion of “contaminated” versus “uncontaminated” transcripts was computed per contig. Any contig with more than 75% of its transcripts flagged as contamination was classified as potentially contaminated and a Note was added to each CDS feature in the gff3 file for this assembly. We detected between 1 and 318 contaminated contigs in 39 of the assemblies (see Supplementary Table S6).

Furthermore, we evaluated each predicted proteome, using the longest isoform per gene, for potential horizontally transferred genes (HGT). In specific, we identified HGT candidates that occurred in one or more Bacillariophyta, but were not conserved in other members of the Ochrophyta. For this, we performed additional DIAMOND searches against donor databases (NCBI RefSeq microbial and plant) and a recipient database (NCBI RefSeq Ochrophyta with all Bacillariophyta removed), using coverage thresholds of at least 50% for both query and subject and an e-value cutoff of 1e-5. Candidate HGTs were initially identified as those aligning to the microbial donor database while failing to align, either to the plant donor, or to the recipient database. We then filtered the HGT candidates by removing those lacking two flanking neighboring genes belonging to the target species, or with (either) flanking genes identified as a contaminant, or at the end of a scaffold (lacking two flanking genes for evaluation). The methodology for HGT identification and downstream filtering is available in EnTAP (v.2.3.0). The remaining genes were retained as HGT candidates (see Supplementary Table S7) and each corresponding CDS feature in the gff3 file was tagged accordingly. We identified between 1 to 129 HGT candidates, per species, in 42 of the annotations.

Orthogroup analysis

We used OrthoFinder to identify orthologous gene groups across species by performing an all-versus-all comparison of protein sequences after removing proteins that are located on genomic sequences that were suspected to be contaminants, and excluding horizontal gene transfer candidates (using the longest isoform of each gene). Based on sequence similarities, genes were grouped into orthogroups, which represent sets of genes descended from a common ancestor. To ensure the reliability of the species tree, we included species from nine publicly available annotations (see Table 3) and also the Oomycota clade for Phytophthora cinnamomi, Phytophthora infestans, Phytophthora ramorum, Phytophthora sojae, and Bremia lactucae (see Table 4).

A species tree (Fig. 4) was generated using OrthoFinder with the -M msa option, which builds gene trees based on multiple sequence alignments (using MAFFT54) and infers their topology with FastTree55. FastTree uses an approximate maximum-likelihood approach and provides SH-like (Shimodaira–Hasegawa-like) support values for each branch, which offer a fast estimate of how reliable each split is—though they are not traditional bootstrap values. These gene trees were then combined using the STAG56 (Species Tree from All Genes) algorithm, which reconstructs the species tree by integrating information from genome-wide orthogroup data, including multi-copy gene families. The support values shown on internal nodes of the species tree reflect how often each grouping is supported across all gene trees. Finally, the tree was rooted using STRIDE (Species Tree Root Inference from Duplication Events)57, which uses gene duplication patterns to determine the most likely root. Altogether, this approach combines gene family structure and duplication history to produce a comprehensive view of species relationships.

The OrthoFinder results files, including orthogroups, are available at58.

Filtering of false positive single exon genes

Descriptive statistics of the raw BRAKER output (see Table 2) and the EnTAP annotation rate (see Supplementary Table S5) suggested that BRAKER overpredicted single-exon genes in some cases. This issue has previously been reported in land plant annotations59.

To address this and filter out potential false positive single-exon gene predictions—while retaining gene models that may be of scientific interest—we applied the following filtering approach: We discarded single-exon gene models that lacked a functional annotation by EnTAP, did not have a significant hit in a DIAMOND search against the NCBI RefSeq non-redundant proteins (NR) database (February 2nd, 2024), and were not part of an orthologous group spanning more than one species in the OrthoFinder results.

File processing

In order to prepare NCBI-compliant GFF3 files, the filtered BRAKER output files were decorated with product names and notes according to EnTAP results (command lines at https://github.com/Gaius-Augustus/Diatom_annotation_scripts).

Ploidy Estimation with Smudgeplot

GenBank accessions were used to retrieve additional metadata from NCBI, including read type, DNA SRA accessions, genome size, and assembly level. Ploidy was not estimated if the SRA accession was unavailable or corresponded to long-read data (i.e., PacBio, ONT). A Nextflow pipeline (available at https://github.com/Gaius-Augustus/Diatom_annotation_scripts) was developed to estimate the ploidy for all remaining individuals in parallel. Paired-end SRA accessions were first fetched using sra-tools and filtered for fungal, bacterial, archaeal, and viral contaminants using Kraken’s60 default parameters. Coverage was calculated before and after contaminants were removed, ranging between 12-499x. Next, FastK built a database for each contaminant-free library using a k-mer size of 21. With the FastK database, Smudgeplot ‘hetmers’ found all k-mer pairs61. The lower k-mer threshold (-L) was estimated with Smudgeplot ‘cutoff’. The final ploidy estimate and proportion of heterozygosity carried by paralogs was extracted from the verbose summary text file resulting from the ‘plot’ module (results in Supplementary Table S8).

Data Records

The data set is available at Zenodo (ref. 62 version v6). It consists of an archive file called Bacillariophyta_annotations.tar.gz. After extraction, the resulting folder Bacillariophyta_annotations contains gff3 format files with gene models (summarized in Table 2) that each correspond to a FASTA format genome file. The accession numbers of the genome assemblies are for user convenience listed in the additionally included file README.md.

Technical Validation

We performed a genome annotation study focusing on 49 diatom species, aiming to create a robust genomic dataset that supports future research into diatom biology and evolution. To emphasize the need for our work, we plotted the distribution of existing Bacillariophyta genome annotations in the context of all known species within this taxon (Fig. 2). This analysis highlights the limited representation of annotated diatom species in current genomic resources. Our work significantly expands the number of annotated assemblies from 9 (or 15, including legacy assemblies) to 58, providing a valuable resource for diatom research.

Descriptive statistics for the gene structures of the newly annotated genomes are provided in Table 2. Previously annotated diatom genomes at NCBI contain between 10,321 and 38,391 protein-coding gene models (see Table 3). The gene numbers in the newly generated gene sets fall within this range. Vuruputoor et al. (2023)59 recommend using the ratio of mono-exon to multi-exon genes as a quality measure for genome annotations, with a suggested ratio of 0.2 for land plants. In contrast, diatom genomes exhibit a higher proportion of single-exon genes, ranging from 0.66 to 2.14 (based on existing annotations; see Table 3). The BRAKER2 and BRAKER3 pipelines tend to overpredict single-exon genes, and we hypothesise that this phenomenon extends to diatom genomes as well. After applying our filtering approach, only five species - Porosira glacialis (3.34), Skeletonema marinoi (2.46), Skeletonema tropicum (2.6), Thalassioria delicatula (2.87), and Thalassiosira mediterranea (2.71) - exceeded this range. These deviations are modest and may partly be attributed to selfish DNA elements, such as unmasked transposons and inserted retroviruses. The exon structure of the novel annotations aligns with previously annotated genomes in terms of the median number of exons per gene (2–3) and the largest number of exons per transcript (13–96) (compare Tables 2 and 3).

Evaluating the quality of novel genome annotations is challenging. We used BUSCO to assess genome completeness at both the genome and protein levels (only the longest isoform per gene), following Earth BioGenome Project guidelines17. BUSCO estimates the proportion of genes typically present as single copies within a clade. However, the stramenopiles_odb10 dataset applicable to diatoms is relatively small (100 marker genes). While BUSCO scores measure sensitivity within this limited dataset (see Fig. 5), a close agreement between genome- and protein-level scores suggests that the new annotations do not lack a significant portion of BUSCO genes detectable at the genome level. This is expected, as the stramenopiles_odb10 dataset was used as input for BRAKER.

BUSCO results of genomes and protein sets (only the longest isoform per gene was used in this analysis). This plot demonstrates the quality of genome assemblies (G = Genome) and predicted protein sets (B = BRAKER) across all here annotated species; species ordered alphabetically. The categories Complete (Single copy or duplicated), Fragmented, or Missing BUSCOs are shown.

We also applied OMArk63 to further assess the quality of protein-coding gene annotations. OMArk uses conserved homologous genes (HOGs) from the OMA database64 and the OMAmer software for fast protein placement65. For Bacillariophyta, the relatively small Ochrophyta subset of 942 HOGs is applicable. While this is a limited number of marker genes, OMArk provides additional metrics, assessing contamination, consistency, and fragmentation. Figure 6 shows OMArk results for our newly annotated genomes, while Fig. 7 displays results for previously available reference genomes. Unlike BUSCO, OMArk correctly handles alternative transcript isoforms, suggesting that the observed duplicates are likely real. Notably, we observed a high level of HOG completeness across most assemblies. However, Thalassiosira profunda and Fistulifera solaris showed a surprisingly high number of duplicate HOGs. For T. profunda, this is consistent with BUSCO scores at the genome level, indicating agreement between different metrics. In contrast, the source of duplicates in F. solaris remains unclear. We explored the genome assembly statistics (Table 5) but found no obvious explanation. Additionally, OMArk identified a significant level of contamination in the genome of Licmophora abbreviata, which had not been flagged as contaminated in public databases (Fig. 8).

OMArk results of newly annotated Bacillariophyta genomes. The top bar graph displays the number of canonical proteins per proteome, the middle graph presents completeness metrics based on single-copy, duplicated, or missing conserved genes, and the bottom graph illustrates the consistency assessment. Proteins are categorized as consistent, contamination, inconsistent, unknown, partial mapping, or fragments. Consistent proteins align with taxonomically expected gene families, while contamination refers to proteins matching gene families from other species. Inconsistent proteins belong to gene families outside the expected lineage but are not contaminants. Unknown proteins cannot be assigned to known gene families and may represent novel or misannotated sequences. Partial mapping indicates proteins aligning with gene families over less than 80% of their sequence, and fragments are proteins shorter than half the median length of their gene family.

OMArk results of previously annotated Bacillariophyta reference genome assemblies. Since it was not straight-forward to extract alternative isoform nesting from the GFF3 files, we extracted the longest isoform for each locus with TSEBRA instead of generating an isoform information file for OMArk. The top bar graph displays the number of canonical proteins per proteome, the middle graph presents completeness metrics based on single-copy, duplicated, or missing conserved genes, and the bottom graph illustrates the consistency assessment. Proteins are categorized as consistent, contamination, inconsistent, unknown, partial mapping, or fragments. Consistent proteins align with taxonomically expected gene families, while contamination refers to proteins matching gene families from other species. Inconsistent proteins belong to gene families outside the expected lineage but are not contaminants. Unknown proteins cannot be assigned to known gene families and may represent novel or miss-annotated sequences. Partial mapping indicates proteins aligning with gene families over less than 80% of their sequence, and fragments are proteins shorter than half the median length of their gene family. These metrics provide a comprehensive evaluation of annotation quality beyond completeness alone.

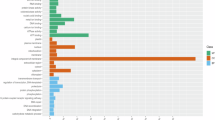

Assignment rate of proteins to orthogroups. The figure shows the percentage of genes assigned to cross-species orthogroups, to single-species orthogroups (paralog only groups), or not assigned to orthogroups across different species as a stacked barplot. The light blue bars represent the genes assigned to orthogroups, while the orange bars represent the unassigned genes. The dark blue bars represent the genes assigned to single-species orthogroups. Previously annotated species are marked in bold face.

To better explain variation in genome-level BUSCO duplication across the diatoms, ploidy was estimated. Fistulifera has already been recognized as an allopolyploid66,67, yielding BUSCO duplication rates between 21% and 89%. While elevated BUSCO duplication can indicate polyploidy in some cases, it may also be a result of incomplete purging, mixed samples, or elevated heterozygosity. Skeletonema marinoi and Thalassiosira profunda, for example, have BUSCO duplication rates of 29% and 26%, respectively, but are still estimated to be diploid. Roberts et al. (2024)68 report the same ploidy levels. Interestingly, the only exception is Stephanodiscus minutulus, which was estimated to be triploid in this study (see Supplementary Table S8).

In the current study, we mainly used the orthogroups constructed by OrthoFinder to filter likely false positive predicted single exon genes. However, the OrthoFinder results themselves are also an interesting result of this study. Across species, the percentage of genes assigned to orthogroups ranged from 85.4% to 99.1%, indicating a generally high rate of orthogroup recovery. For most species, over 90% of genes were successfully assigned, with especially high assignment rates observed in Skeletonema marinoi (99.1%), Discostella pseudostelligera (98.9%) and Skeletonema menzelii (98.9%) (Fig. 8). A few species, such as Thalassiosira delicatula (85.4%) and Bremia lactucae (species from the outgroup used for the OrthoFinder analysis) (89.8%), showed slightly lower assignment rates, potentially reflecting lineage-specific gene content. It should be noted that OrthoFinder also constructs intra-species orthogroups, which consist of genes from a single species.

In total, 1,115,003 genes (96,8% of the dataset) were assigned to inter-species orthogroups, emphasizing the significant degree of genetic overlap among the species included in this study. Orthogroup inference resulted in a total of 7,092 species-specific orthogroups, comprising 29,717 genes, which represents 2.6% of all input genes. It points to potential species-specific adaptations, with these gene families possibly linked to unique ecological roles or environmental responses. The mean orthogroup size was 32.7 genes, while the median size was 6.0, reflecting a skewed distribution with some large, highly conserved orthogroups. The G50 (i.e., the orthogroup size above which 50% of all assigned genes are found) was 87 for assigned genes and 119 when considering all input genes. The corresponding O50 values—representing the number of the largest orthogroups containing half of the genes—were 2,577 and 4,381, respectively. Notably, only 178 orthogroups included genes from all species. The relatively low number of orthogroups containing genes from all species (262) suggests a high level of gene family diversification, likely reflecting extensive evolutionary divergence and possible lineage-specific expansions or losses across the dataset. The total number of genes per species varied widely, from less than 10,000 in Discostella pseudostelligera to almost 36,000 in Seminavis robusta (see statistics per species in the Supplementary Table S9), highlighting the diversity in genome size across the dataset.

OrthoFinder’s analysis is based on the construction of gene trees, allowing for the classification of orthologous and paralogous relationships. The gene trees can be summarized in species trees, which are particularly useful for identifying variable rates of sequence evolution (through branch lengths) and the order in which sequences diverged (tree topology). The resulting species tree for Bacillariophyta gene sets, including both novel and previously annotated genomes from the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration (INDSC), is shown in Fig. 4.

The species were grouped into major sub-lineages: Coscinodiscophyceae, Mediophyceae, Fragilariophyceae, and Bacillariophyceae. Consistent with findings from earlier phylogenetic research69,70, diatom sub-lineages are not recovered as a monophyletic group: radial centrics (Coscinodiscophyceae) form a paraphyletic clade, while Mediophyceae and pennate diatoms (Fragilariophyceae and Bacillariophyceae) form separate, well-supported clades. Chaetoceros muelleri and Chaetoceros tenuissimus are often placed outside the main Coscinodiscophyceae (radial centric) clade and instead fall within the Mediophyceae, a group of polar centric diatoms69,70,71. Mediophyceae regularly emerge as the sister group to pennate diatoms (Fragilariophyceae and Bacillariophyceae), rather than to radial centrics. Chaetoceros species cluster with other Mediophyceae such as Thalassiosira, Biddulphia, and Rhizosolenia, forming a distinct group separate from radial centrics and generally closer to pennate diatoms. This placement supports earlier morphological and phylogenetic studies72,73 showing that chain-forming centrics like Chaetoceros are more closely related to pennates than to traditional radial centrics.

In some cases, the effect of excluding contaminant and HGT candidate sequences may have been slightly too stringent, potentially leading to overfiltering. To illustrate, we provide BUSCO scores for both the original and genome assemblies and gene sets without contaminant and HGT-labeled sequences (see Supplementary Table S10).

While the PhycoCosm database includes additional annotated Bacillariophyta genomes, our workflow was specifically designed to rely on automatic querying of NCBI datasets for genome downloads. Therefore, we did not include PhycoCosm genomes in this study.

The novel annotations presented here will be valuable for studying interactions between diatoms and bacteria, particularly in the context of algal blooms that play a significant role in global carbon cycling. Given that methods for recovering full eukaryotic genomes from metagenomes are still developing, reference-based binning approaches, such as BlobTools74 using DIAMOND, may provide a viable strategy, especially as databases like NCBI NR expand for this clade.

Code availability

The snakemake workflow used to generated this data set is freely available at https://github.com/KatharinaHoff/braker-snake. The postprocessing steps including custom scripts are freely available at https://github.com/Gaius-Augustus/Diatom_annotation_scripts. Container and software versions are listed in Supplementary Table S4.

References

Falciatore, A., Jaubert, M., Bouly, J.-P., Bailleul, B. & Mock, T. Diatom molecular research comes of age: model species for studying phytoplankton biology and diversity. Plant Cell 32, 547–572 (2020).

Schaum, C.-E., Buckling, A., Smirnoff, N., Studholme, D. J. & Yvon-Durocher, G. Environmental fluctuations accelerate molecular evolution of thermal tolerance in a marine diatom. Nat. Commun. 9, 1719 (2018).

Sethi, D., Butler, T. O., Shuhaili, F. & Vaidyanathan, S. Diatoms for Carbon Sequestration and Bio-Based Manufacturing. Biology (Basel) 9 (2020).

Jaramillo-Madrid, A. C., Ashworth, J., Fabris, M. & Ralph, P. J. Phytosterol biosynthesis and production by diatoms (Bacillariophyceae). Phytochemistry 163, 46–57 (2019).

Matsuda, Y. & Kroth, P. G. Carbon fixation in diatoms. in The structural basis of biological energy generation (ed. Hohmann-Marriott, M. F.) vol. 39 335–362 (Springer Netherlands, 2014).

Li, X., Roevros, N., Dehairs, F. & Chou, L. Biological responses of the marine diatom Chaetoceros socialis to changing environmental conditions: A laboratory experiment. PLoS ONE 12, e0188615 (2017).

Ellegaard, M. et al. The fascinating diatom frustule—can it play a role for attenuation of UV radiation? J. Appl. Phycol. 28, 3295–3306 (2016).

Bayramova, E. M., Bedoshivili, Y. D. & Likhoshway, Y. V. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of diatom response to environmental changes. Limnology and Freshwater Biology 20–30 (2023).

Moreno, C. M. et al. Molecular physiology of Antarctic diatom natural assemblages and bloom event reveal insights into strategies contributing to their ecological success. mSystems 9, e0130623 (2024).

Di Costanzo, F., Di Dato, V. & Romano, G. Diatom-Bacteria Interactions in the Marine Environment: Complexity, Heterogeneity, and Potential for Biotechnological Applications. Microorganisms 11 (2023).

Amin, S. A., Parker, M. S. & Armbrust, E. V. Interactions between diatoms and bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 76, 667–684 (2012).

Teeling, H. et al. Substrate-controlled succession of marine bacterioplankton populations induced by a phytoplankton bloom. Science 336, 608–611 (2012).

Siebers, R. et al. Marine particle microbiomes during a spring diatom bloom contain active sulfate-reducing bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 100 (2024).

Branscombe, L. et al. Cryptic bacterial pathogens of diatoms peak during senescence of a winter diatom bloom. New Phytol. 241, 1292–1307 (2024).

Coyne, K. J., Wang, Y. & Johnson, G. Algicidal bacteria: A review of current knowledge and applications to control harmful algal blooms. Front. Microbiol. 13, 871177 (2022).

Grigoriev, I. V. et al. PhycoCosm, a comparative algal genomics resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D1004–D1011 (2021).

Lawniczak, M. K. N. et al. Standards recommendations for the Earth BioGenome Project. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 119 (2022).

Plant and Algal Genomics Lab, Institut de Biologie, École Normale Supérieure. SRX18295403: GSM6736688: Return_to_Light_24h.Biorep2; Fragilariopsis cylindrus; RNA-Seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR22322166 (2023).

Mölder, F. et al. Sustainable data analysis with Snakemake. F1000Res. 10, 33 (2021).

Kurtzer, G. M., Sochat, V. & Bauer, M. W. Singularity: Scientific containers for mobility of compute. PLoS ONE 12, e0177459 (2017).

Zdobnov, E. M. et al. OrthoDB in 2020: evolutionary and functional annotations of orthologs. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D389–D393 (2021).

Katz, K. et al. The Sequence Read Archive: a decade more of explosive growth. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D387–D390 (2022).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907–915 (2019).

Danecek, P. et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 10 (2021).

Traller, J. C. et al. Genome and methylome of the oleaginous diatom Cyclotella cryptica reveal genetic flexibility toward a high lipid phenotype. Biotechnol. Biofuels 9, 258 (2016).

Roberts, W. R., Downey, K. M., Ruck, E. C., Traller, J. C. & Alverson, A. J. Improved Reference Genome for Cyclotella cryptica CCMP332, a Model for Cell Wall Morphogenesis. Salinity Adaptation, and Lipid Production in Diatoms (Bacillariophyta). G3 (Bethesda) 10, 2965–2974 (2020).

University of Gothenburg. SRX20979717: RNA-Seq of Skeletonema marinoi. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR25233272 (2023).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117, 9451–9457 (2020).

Brůna, T., Hoff, K. J., Lomsadze, A., Stanke, M. & Borodovsky, M. BRAKER2: automatic eukaryotic genome annotation with GeneMark-EP + and AUGUSTUS supported by a protein database. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 3, lqaa108 (2021).

Gabriel, L. et al. BRAKER3: Fully automated genome annotation using RNA-seq and protein evidence with GeneMark-ETP, AUGUSTUS, and TSEBRA. Genome Res. 34, 769–777 (2024).

Seppey, M., Manni, M. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness. Methods Mol. Biol. 1962, 227–245 (2019).

Huang, N. & Li, H. compleasm: a faster and more accurate reimplementation of BUSCO. Bioinformatics 39 (2023).

Brůna, T., Lomsadze, A. & Borodovsky, M. GeneMark-EP + : eukaryotic gene prediction with self-training in the space of genes and proteins. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 2, lqaa026 (2020).

Lomsadze, A., Ter-Hovhannisyan, V., Chernoff, Y. O. & Borodovsky, M. Gene identification in novel eukaryotic genomes by self-training algorithm. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 6494–6506 (2005).

Ter-Hovhannisyan, V., Lomsadze, A., Chernoff, Y. O. & Borodovsky, M. Gene prediction in novel fungal genomes using an ab initio algorithm with unsupervised training. Genome Res. 18, 1979–1990 (2008).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59–60 (2015).

Iwata, H. & Gotoh, O. Benchmarking spliced alignment programs including Spaln2, an extended version of Spaln that incorporates additional species-specific features. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e161 (2012).

Stanke, M., Diekhans, M., Baertsch, R. & Haussler, D. Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding. Bioinformatics 24, 637–644 (2008).

Hoff, K. J. & Stanke, M. Predicting Genes in Single Genomes with AUGUSTUS. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 65, e57 (2019).

Gabriel, L., Hoff, K. J., Brůna, T., Borodovsky, M. & Stanke, M. TSEBRA: transcript selector for BRAKER. BMC Bioinformatics 22, 566 (2021).

Brůna, T., Gabriel, L. & Hoff, K. J. Navigating Eukaryotic Genome Annotation Pipelines: A Route Map to BRAKER, Galba, and TSEBRA. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2403.19416 (2024).

Brůna, T., Lomsadze, A. & Borodovsky, M. GeneMark-ETP significantly improves the accuracy of automatic annotation of large eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 34, 757–768 (2024).

Kovaka, S. et al. Transcriptome assembly from long-read RNA-seq alignments with StringTie2. Genome Biol. 20, 278 (2019).

Tang, S., Lomsadze, A. & Borodovsky, M. Identification of protein coding regions in RNA transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e78 (2015).

Hart, A. J. et al. EnTAP: Bringing faster and smarter functional annotation to non-model eukaryotic transcriptomes. Mol. Ecol. Resour 20, 591–604 (2020).

O’Leary, N. A. et al. Reference sequence (RefSeq) database at NCBI: current status, taxonomic expansion, and functional annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D733–45 (2016).

UniProt Consortium. Uniprot: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D523–D531 (2023).

Hernández-Plaza, A. et al. eggNOG 6.0: enabling comparative genomics across 12 535 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D389–D394 (2023).

Cantalapiedra, C. P., Hernández-Plaza, A., Letunic, I., Bork, P. & Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 5825–5829 (2021).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene Ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 25, 25–29 (2000).

Gene Ontology Consortium. et al. The Gene Ontology knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics 224, iyad031 (2023).

Mistry, J. et al. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D412–D419 (2021).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D587–D592 (2023).

Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K. & Miyata, T. MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066 (2002).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. FastTree 2 — approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE 5, e9490 (2010).

Emms, D. & Kelly, S. STAG: Species Tree Inference from All Genes. BioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/267914 (2018).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. STRIDE: Species Tree Root Inference from Gene Duplication Events. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 3267–3278 (2017).

Nenasheva, N. et al. OrthoFinder Results of Gene Annotations of 49 Bacillariophyta Genome Assemblies. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15380858 (2025).

Vuruputoor, V. S. et al. Welcome to the big leaves: Best practices for improving genome annotation in non-model plant genomes. Appl. Plant Sci. 11, e11533 (2023).

Wood, D. E. & Salzberg, S. L. Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol. 15, R46 (2014).

Ranallo-Benavidez, T. R., Jaron, K. S. & Schatz, M. C. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat. Commun. 11, 1432 (2020).

Nenasheva, N. et al. Gene Annotations of 49 Bacillariophyta Genome Assemblies. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13745090 (2025).

Nevers, Y. et al. Quality assessment of gene repertoire annotations with OMArk. Nat. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-024-02147-w (2024).

Altenhoff, A. M. et al. OMA orthology in 2024: improved prokaryote coverage, ancestral and extant GO enrichment, a revamped synteny viewer and more in the OMA Ecosystem. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, D513–D521 (2024).

Rossier, V., Warwick Vesztrocy, A., Robinson-Rechavi, M. & Dessimoz, C. OMAmer: tree-driven and alignment-free protein assignment to subfamilies outperforms closest sequence approaches. Bioinformatics 37, 2866–2873 (2021).

Tanaka, T. et al. Oil accumulation by the oleaginous diatom Fistulifera solaris as revealed by the genome and transcriptome. Plant Cell 27, 162–176 (2015).

University of Sydney. SRX17002520: Diverse RNA viruses associated with diatom, eustigmatophyte, dinoflagellate and rhodophyte microalgae cultures. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR20985051 (2022).

Roberts, W. R., Siepielski, A. M. & Alverson, A. J. Diatom abundance in the polar oceans is predicted by genome size. PLoS Biol. 22, e3002733 (2024).

Parks, M. B., Wickett, N. J. & Alverson, A. J. Signal, uncertainty, and conflict in phylogenomic data for a diverse lineage of microbial eukaryotes (diatoms, bacillariophyta). Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 80–93 (2018).

Theriot, E. C. A preliminary multigene phylogeny of the diatoms (Bacillariophyta): challenges for future research. Plant Ecol. Evol. 143, 278–296 (2010).

Xu, Q., Cui, Z. & Chen, N. Comparative analysis of chloroplast genomes of seven chaetoceros species revealed variation hotspots and speciation time. Front. Microbiol. 12, 742554 (2021).

Medlin, L. K. & Kaczmarska, I. Evolution of the diatoms: V. Morphological and cytological support for the major clades and a taxonomic revision. Phycologia 43, 245–270 (2004).

Nakov, T., Beaulieu, J. M. & Alverson, A. J. Accelerated diversification is related to life history and locomotion in a hyperdiverse lineage of microbial eukaryotes (Diatoms, Bacillariophyta). New Phytol. 219, 462–473 (2018).

Laetsch, D. R. & Blaxter, M. L. BlobTools: Interrogation of genome assemblies [version 1; peer review: 2 approved with reservations]. F1000Res. 6, 1287 (2017).

CNRS-AMU. Genome assembly ASM225602v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_002256025.1/ (2017).

CNRS-AMU. SRX2949863: RNA-seq of Asterionella formosa BG1 in mixed culture. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR5749612 (2017).

Oliver, A. et al. Diploid genomic architecture of Nitzschia inconspicua, an elite biomass production diatom. Sci. Rep. 11, 15592 (2021).

University of California, San Diego. Genome assembly GAI293_CANU_175m_combined - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_019154785.2/ (2021).

Shibl, A. A. et al. Diatom modulation of select bacteria through use of two unique secondary metabolites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117, 27445–27455 (2020).

NYUAD. Genome of Asterionellopsis glacialis - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_014885115.2/ (2020).

Picardie Jules Verne University. Genome assembly ASM1959358v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_019593585.1/ (2021).

OKAYAMA. DRX185892: Illumina HiSeq. 2500 paired end sequencing of SAMD00191360. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=DRR195451 (2021).

EcoLab. SRX4900118: RNA-seq of Nitzschia palea exposed to high FLG concentration. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR8072139 (2019).

EcoLab. SRX4900117: RNA-seq of Nitzschia palea exposed to high CNT concentration. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR8072140 (2019).

EcoLab. SRX4900116: RNA-seq of Nitzschia palea control condition. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR8072141 (2019).

EcoLab. SRX4900114: RNA-seq of Nitzschia palea exposed to FLG shading. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR8072143 (2019).

EcoLab. SRX4900113: RNA-seq of Nitzschia palea exposed to low CNT concentration. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR8072144 (2019).

Roberts, W. R., Ruck, E. C., Downey, K. M., Pinseel, E. & Alverson, A. J. Resolving Marine-Freshwater Transitions by Diatoms Through a Fog of Gene Tree Discordance. Syst. Biol. 72, 984–997 (2023).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3735623v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_037356235.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833690: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733610 (2023).

Kamikawa, R. et al. Genome evolution of a nonparasitic secondary heterotroph, the diatom Nitzschia putrida. Sci. Adv. 8, eabi5075 (2022).

Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University. Genome assembly Nputr_1.0 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_016586335.1/ (2020).

Davison, H. R., Hurst, G. D. D. & Siozios, S. “Candidatus Megaira” are diverse symbionts of algae and ciliates with the potential for defensive symbiosis. Microb. Genom. 9 (2023).

New York University AbuDhabi, UAE. Genome assembly ASM1969354v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_019693545.1/ (2021).

University of Technology Sydney. SRX5445774: mRNA-seq of Chaeotoceros muelleri exposed to Flu at t = 72hrs, replicate 2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR8647946 (2021).

University of Technology Sydney. SRX5445772: mRNA-seq of Chaeotoceros muelleri exposed to control at t = 48hrs, replicate ctl. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR8647948 (2021).

University of Technology Sydney. SRX5445771: mRNA-seq of Chaeotoceros muelleri exposed to Fen at t = 48hrs, replicate 3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR8647949 (2021).

University of Technology Sydney. SRX5445770: mRNA-seq of Chaeotoceros muelleri exposed to Fen at t = 48hrs, replicate 2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR8647950 (2021).

University of Technology Sydney. SRX5445741: mRNA-seq of Chaeotoceros muelleri exposed to Ro at t = 24hrs, replicate 3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR8647979 (2020).

University of Technology Sydney. SRX5445737: mRNA-seq of Chaeotoceros muelleri exposed to Flu at t = 72hrs, replicate 3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR8647983 (2021).

Bowler, C. et al. The Phaeodactylum genome reveals the evolutionary history of diatom genomes. Nature 456, 239–244 (2008).

Diatom Consortium. Genome assembly ASM15095v2 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCF_000150955.2/ (2008).

Hongo, Y. et al. The genome of the diatom Chaetoceros tenuissimus carries an ancient integrated fragment of an extant virus. Sci. Rep. 11, 22877 (2021).

Environmental Genomics Group, Research Center for Bioinformatics and Biosciences, National Research Institute of Fisheries Science, Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency. Genome assembly Cten210_1.0 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_021927905.1/ (2021).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693939v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939395.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833699: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733601 (2023).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693933v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939335.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833779: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733581 (2023).

Chicago Botanic Garden. Genome assembly ASM863298v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_008632985.1/ (2019).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3694002v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036940025.1/ (2024).

CNRS. SRX1078771: Tw reference transcriptome. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR2085009 (2016).

Turk Dermastia, T., Dall’Ara, S., Dolenc, J. & Mozetič, P. Toxicity of the Diatom Genus Pseudo-nitzschia (Bacillariophyceae): Insights from Toxicity Tests and Genetic Screening in the Northern Adriatic Sea. Toxins (Basel) 14 (2022).

Basu, S. et al. Finding a partner in the ocean: molecular and evolutionary bases of the response to sexual cues in a planktonic diatom. New Phytol. 215, 140–156 (2017).

Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn. Genome assembly ASM90066040v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_900660405.1/ (2019).

Zackova Suchanova, J. et al. Diatom adhesive trail proteins acquired by horizontal gene transfer from bacteria serve as primers for marine biofilm formation. New Phytol. 240, 770–783 (2023).

B CUBE. Genome assembly DD_uo2022 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_026770025.1/ (2022).

Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Genome assembly ASM3735574v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_037355745.1/ (2024).

Assembly: GCA_900660405.1 - ENA - EBI. https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/GCA_900660405.1 (2023).

J. Crag Venter Institute. SRX3899616: P. multiseries grown at 20uM phosphate, 400ppm pCO2, rep C (totalRNA). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR6956622 (2018).

J. Crag Venter Institute. SRX3899615: P. multiseries grown at 20uM phosphate, 400ppm pCO2, rep B (totalRNA). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR6956623 (2018).

J. Crag Venter Institute. SRX3899610: P. multiseries grown at 0.5uM phosphate, 220ppm pCO2, rep A (totalRNA). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR6956628 (2018).

J. Crag Venter Institute. SRX3899605: P. multiseries grown at 0.5uM phosphate, 730ppm pCO2, rep C (polyA). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR6956633 (2018).

J. Crag Venter Institute. SRX3899601: P. multiseries grown at 20uM phosphate, 400ppm pCO2, rep A (polyA). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR6956637 (2018).

J. Crag Venter Institute. SRX3899600: P. multiseries grown at 20uM phosphate, 400ppm pCO2, rep B (polyA). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR6956638 (2018).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693967v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939675.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833793: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733507 (2023).

Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Genome assembly ASM3735585v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_037355855.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693997v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939975.1/ (2024).

Osuna-Cruz, C. M. et al. The Seminavis robusta genome provides insights into the evolutionary adaptations of benthic diatoms. Nat. Commun. 11, 3320 (2020).

Center for Plant Systems Biology, VIB-Ugent. Genome assembly Semro_V1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_903772945.1/ (2022).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693993v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939935.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833788: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733512 (2023).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833751: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733549 (2023).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833688: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733612 (2023).

Sorokina, M. et al. Draft genome assembly and sequencing dataset of the marine diatom Skeletonema cf. costatum RCC75. Data Brief 41, 107931 (2022).

Balance of the Microverse. Genome assembly FSU_Scostatum_1.0 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_018806925.1/ (2021).

NAGAHAMA_BIO. DRX141855: Illumina HiSeq. 2000 paired end sequencing of SAMD00137718. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=DRR151104 (2018).

NAGAHAMA_BIO. DRX141856: Illumina HiSeq. 2000 paired end sequencing of SAMD00137719. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=DRR151105 (2018).

NAGAHAMA_BIO. DRX141857: Illumina HiSeq. 2000 paired end sequencing of SAMD00137720. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=DRR151106 (2018).

NAGAHAMA_BIO. DRX141858: Illumina HiSeq. 2000 paired end sequencing of SAMD00137721. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=DRR151107 (2018).

NAGAHAMA_BIO. DRX141859: Illumina HiSeq. 2000 paired end sequencing of SAMD00137722. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=DRR151108 (2018).

NAGAHAMA_BIO. DRX141860: Illumina HiSeq. 2000 paired end sequencing of SAMD00137723. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=DRR151109 (2018).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693963v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939635.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833803: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733497 (2023).

Liu, S., Xu, Q. & Chen, N. Expansion of photoreception-related gene families may drive ecological adaptation of the dominant diatom species Skeletonema marinoi. Sci. Total Environ. 897, 165384 (2023).

Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Genome assembly ASM3054422v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_030544225.1/ (2023).

University of Gothenburg. Genome assembly GU_Smar_1.1.8 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_030871285.1/ (2023).

University of Gothenburg. SRX20979719: RNA-Seq of Skeletonema marinoi. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR25233270 (2023).

University of Gothenburg. SRX20979712: RNA-Seq of Skeletonema marinoi. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR25233277 (2023).

University of Gothenburg. SRX20979710: RNA-Seq of Skeletonema marinoi. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR25233279 (2023).

University of Gothenburg. SRX20979704: RNA-Seq of Skeletonema marinoi. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR25233285 (2023).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693985v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939855.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833746: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733553 (2023).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3694000v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036940005.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833727: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733572 (2023).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM1318728v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_013187285.1/ (2020).

Lewis Lab, Biological Sciences, University of Arkansas. SRX15830763: GSM6261389: CCMP332_1hr_0ppt_rep3; Cyclotella cryptica; RNA-Seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR19991157 (2022).

Lewis Lab, Biological Sciences, University of Arkansas. SRX15830764: GSM6261390: CCMP332_2hr_0ppt_rep1; Cyclotella cryptica; RNA-Seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR19991158 (2022).

Lewis Lab, Biological Sciences, University of Arkansas. SRX15830768: GSM6261394: CCMP332_30m_0ppt_rep2; Cyclotella cryptica; RNA-Seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR19991160 (2022).

Lewis Lab, Biological Sciences, University of Arkansas. SRX15830773: GSM6261399: CCMP332_8hr_0ppt_rep1; Cyclotella cryptica; RNA-Seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR19991165 (2022).

Lewis Lab, Biological Sciences, University of Arkansas. SRX15830778: GSM6261404: CCMP332_Control_rep3; Cyclotella cryptica; RNA-Seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR19991170 (2022).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3694010v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036940105.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833771: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733529 (2023).

Audoor, S. et al. Transcriptional chronology reveals conserved genes involved in pennate diatom sexual reproduction. Mol. Ecol. 33, e17320 (2024).

Universiteit Gent. Genome assembly Cyc-CA1.15-REFERENCE-ANNOTATED - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_933822405.4/ (2023).

Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Genome assembly ASM3717862v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_037178625.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833772: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733528 (2023).

New York University AbuDhabi, UAE. Genome assembly ASM1969352v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_019693525.1/ (2021).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3694004v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036940045.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833722: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733577 (2023).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693941v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939415.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833776: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733524 (2023).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833691: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733609 (2023).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693943v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939435.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833769: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733531 (2023).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3694008v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036940085.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833794: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733506 (2023).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833734: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733565 (2023).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693975v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939755.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833796: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733504 (2023).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693973v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939735.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833791: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733509 (2023).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693965v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939655.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833806: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733494 (2023).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693955v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939555.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833759: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733541 (2023).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693983v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939835.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833781: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733519 (2023).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833705: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733595 (2023).

WELLCOME SANGER INSTITUTE. Genome assembly uoEpiScrs1.2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_946965045.2/ (2023).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693989v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939895.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833737: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733562 (2023).

Maeda, Y. et al. Chromosome-Scale Genome Assembly of the Marine Oleaginous Diatom Fistulifera solaris. Mar. Biotechnol. 24, 788–800 (2022).

Institute of Engineering, Division of Biotechnology and Life Science, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology. Genome assembly Fpelliculosa_ONT_v02 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_026008555.1/ (2022).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3735621v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_037356215.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833780: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733520 (2023).

Institute of Engineering, Division of Biotechnology and Life Science, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology. Genome assembly Fsolaris_ONT_v03reference - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_030295235.1/ (2022).

Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology. Genome assembly Fsol_1.0 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_002217885.1/ (2017).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693959v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939595.1/ (2024).

Zepernick, B. N., Truchon, A. R., Gann, E. R. & Wilhelm, S. W. Draft Genome Sequence of the Freshwater Diatom Fragilaria crotonensis SAG 28.96. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 11, e0028922 (2022).

Zepernick, B. N. et al. Morphological, physiological, and transcriptional responses of the freshwater diatom Fragilaria crotonensis to elevated pH conditions. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1044464 (2022).

University of Tennessee Knoxville. Genome assembly ASM2292589v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_022925895.1/ (2022).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833756: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733544 (2023).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833742: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733557 (2023).

Galachyants, Y. P. et al. Sequencing of the complete genome of an araphid pennate diatom Synedra acus subsp. radians from Lake Baikal. Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 461, 84–88 (2015).

LIMNOLOGICAL INSTITUTE SB RAS. Genome assembly sac1- NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_900642245.1/ (2019).

Limnological Institute SB RAS. SRX4509102: Fragilaria radians RNA-seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR7646146 (2019).

Limnological Institute SB RAS. SRX4509101: Fragilaria radians RNA-seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR7646147 (2019).

Limnological Institute SB RAS. SRX4509100: Fragilaria radians RNA-seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR7646148 (2019).

Limnological Institute SB RAS. SRX4509099: Fragilaria radians RNA-seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR7646149 (2019).

Limnological Institute SB RAS. SRX4509098: Fragilaria radians RNA-seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR7646150 (2019).

New York University AbuDhabi, UAE. Genome assembly ASM1969357v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_019693575.1/ (2021).

DFG Cluster of Excellence “Future Ocean.” Genome assembly ThaOc_1.0 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_000296195.2/ (2012).

NCBI (GEO). SRX13155147: GSM5692981: LCuA rep2; Thalassiosira oceanica CCMP1005; RNA-Seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR16963171 (2021).

NCBI (GEO). SRX13155149: GSM5692982: LCuA rep3; Thalassiosira oceanica CCMP1005; RNA-Seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR16963172 (2021).

Armbrust, Oceanography, University of Washingtom. SRX18196720: GSM6720087: To Hydrogren peroxide N2; Thalassiosira oceanica; RNA-Seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR22218830 (2022).

Armbrust, Oceanography, University of Washingtom. SRX18196719: GSM6720086: To Hydrogren peroxide N1; Thalassiosira oceanica; RNA-Seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR22218832 (2022).

Armbrust, Oceanography, University of Washingtom. SRX18196718: GSM6720085: To Control N3; Thalassiosira oceanica; RNA-Seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR22218838 (2022).

Paajanen, P. et al. Building a locally diploid genome and transcriptome of the diatom Fragilariopsis cylindrus. Sci. Data 4, 170149 (2017).

TGAC. Genome assembly Fc_falcon_quiver_polished - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_900095095.1/ (2016).

JGI-PGF. Genome assembly Fracy1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_001750085.1/ (2016).

Plant and Algal Genomics Lab, Institut de Biologie, École Normale Supérieure. SRX18295413: GSM6736698: Return_to_Light_5days.Biorep3; Fragilariopsis cylindrus; RNA-Seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR22322156 (2023).

Plant and Algal Genomics Lab, Institut de Biologie, École Normale Supérieure. SRX18295408: GSM6736693: Return_to_Light_3days.Biorep1; Fragilariopsis cylindrus; RNA-Seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR22322161 (2023).

Plant and Algal Genomics Lab, Institut de Biologie, École Normale Supérieure. SRX18295407: GSM6736692: Return_to_Light_48h.Biorep3; Fragilariopsis cylindrus; RNA-Seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR22322162 (2023).

Plant and Algal Genomics Lab, Institut de Biologie, École Normale Supérieure. SRX18295399: GSM6736684: Return_to_Light_12h.Biorep1; Fragilariopsis cylindrus; RNA-Seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR22322170 (2023).

Plant and Algal Genomics Lab, Institut de Biologie, École Normale Supérieure. SRX18295398: GSM6736683: Return_to_Light_6h.Biorep3; Fragilariopsis cylindrus; RNA-Seq. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR22322171 (2023).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693969v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939695.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833798: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733502 (2023).

IBENS. Genome assembly CCMP470 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_900291995.1/ (2018).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693987v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939875.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833748: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733551 (2023).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833721: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733578 (2023).

Suzuki, S. et al. Rapid transcriptomic and physiological changes in the freshwater pennate diatom Mayamaea pseudoterrestris in response to copper exposure. DNA Res. 29 (2022).

National Institute for Environmental Studies. Genome assembly Mpse_1.0 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_027923505.1/ (2022).

Armbrust, E. V. et al. The genome of the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana: ecology, evolution, and metabolism. Science 306, 79–86 (2004).

Diatom Consortium Genome assembly ASM14940v2 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCF_000149405.2/ (2009).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3694012v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036940125.1/ (2014).

Universidad Mayor. SRX10228342: RNA-Seq of RCC4660. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR13846812 (2021).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833711: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733589 (2023).

University of Arkansas. Genome assembly ASM3693935v1 - NCBI - NLM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_036939355.1/ (2024).

University of Arkansas. SRX14833695: Phylogenomics of the Thalassiosirales. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR18733605 (2023).

Anisimova, M. & Gascuel, O. Approximate likelihood-ratio test for branches: A fast, accurate, and powerful alternative. Syst. Biol. 55, 539–552 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We thank Stepan Saenko for discussing the snakemake workflow for structural genome annotation. NN was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) in the framework of the research unit FOR2406 “Proteogenomics of Marine Polysaccharide Utilization (POMPU)” by a grant to KJH (277249973). CW and AH, and their software, were supported by a grant to JLW (NSF DBI 1943371).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.J.H. and M.M.B. conceptualised the study. C.P. and K.J.H. designed and implemented the software. C.P. executed the snakemake workflow for structural genome annotation under supervision of K.J.H. C.W. and A.H. performed functional annotation under supervision of J.L.W. C.W. performed ploidy analysis under supervision of J.L.W. A.H. performed horizontal gene transfer analysis under supervision of J.L.W. N.N. performed orthology analysis under supervision of K.J.H. N.N. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript in writing. All authors read and approved of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nenasheva, N., Pitzschel, C., Webster, C.N. et al. Annotation of protein-coding genes in 49 diatom genomes from the Bacillariophyta clade. Sci Data 12, 985 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05306-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05306-z

This article is cited by

-

Diatoms in low pH environments: diversity, adaptations, mechanisms, ecological roles, and applications

Archives of Microbiology (2025)