Abstract

The pinna-related transfer function (PRTF) is critical for localizing and perceiving sound in three-dimensional space. PRTF largely depends on individual spectral cues and the unique physiology of the pinna, necessitating high-resolution data for accurate acoustic modeling. The accuracy of personalized acoustic models could be significantly improved using high-precision physiological data and incorporating advanced simulation methods such as the boundary element method (BEM). We describe a comprehensive dataset of 150 bilateral PRTFs from 75 participants to support developing, improving, and validating personalized PRTF modeling methods. The dataset includes simulated results from binaural laser-scanned models that are accurately validated through empirical measurements. This comprehensive dataset will contribute to acoustic and spatial audio research and support the ongoing advancements in personalized PRTF modeling techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The pinna plays a critical role in human auditory perception. The unique shape and complex structure of the pinna can alter the propagation path of sound waves, resulting in the pinna effect, which leads to changes in directional and spectral characteristics1,2.

The pinna-related transfer function (PRTF) is closely related to the pinna effect. It describes the spectral changes that sound undergoes as it propagates from the sound source to the entrance of the ear canal, reflecting the interaction between sound waves and the pinna structure. The PRTF encodes information about the spatial location of sound sources, including lateral and polar angle, making it valuable for research into auditory functions such as sound localization. The pinna’s reflection, diffraction, and resonance effects create a series of notches and peaks in the PRTF spectrum. The position and strength of these notches and peaks vary with changes in the lateral angle of the sound source, providing cues about the source’s direction.

The PRTF can be obtained through two primary approaches: measurement and simulation. The measurement method often faces challenges such as the requirement of specialized equipment, the complexity of setting up the experimental environment, and the time-consuming nature of the process. The simulation method is based on acoustic theory, where a numerical model of the human pinna is established, and the propagation of sound waves within this model can be calculated to obtain the PRTF. Based on a numerical model, simulation offers greater flexibility and efficiency, allowing for rapid adjustments and extensive testing under different conditions, making it a valuable alternative for PRTF acquisition. Three main technical approaches for obtaining pinna geometric models are medical imaging3, 2D image-based reconstruction4, and 3D laser scanning5. Compared to Magnetic Resonance Imaging and 2D-3D reconstruction, 3D laser scanning technology offers fast acquisition, low costs, and convenient model construction, making it suitable for building high-quality 3D pinna model datasets.

Numerical computation methods have been widely applied in acoustic research and are invaluable for accurately solving complex acoustic problems. They enable precise simulations of wave propagation and sound interactions with intricate geometries such as the pinna, offering benefits in terms of computational efficiency and robust validation against experimental data. Both the finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method6 and the finite element method (FEM)7 have been successfully applied in the acoustic simulation of PRTFs. In contrast, the boundary element method (BEM) stands out for its ability to reduce the computational load by discretizing only the surface of objects, thus offering distinct advantages for PRTF modeling. BEM can be used to calculate PRTF in the frequency range up to 20 kHz and can be coupled with the fast multipole method to develop the Fast Multipole Boundary Element Method (FM-BEM), which improves computational speed and extends the frequency solution range8,9. BEM is particularly effective for high-frequency simulations in PRTF modeling, as it naturally handles open-domain problems and generally provides more accurate results compared to FDTD and FEM, which can be more computationally expensive and often require artificial boundary conditions.

A dataset for acoustic research was developed, comprising 150 high-resolution (0.1 mm) PRTFs from 75 subjects, obtained through simulations using the boundary element method. Each model is accompanied by 20 anthropometric measurements of the pinna, acquired following standard protocols. Compared to existing datasets such as SONICOM10 (0.5 mm resolution) and WiDESPREaD11 (unilateral), this dataset offers a more representative sample of pinna morphology with 0.1 mm scanning precision, includes bilateral data for all 75 participants, and features a balanced 8:7 gender distribution, significantly enhancing its research value. This dataset enables a comprehensive investigation into the relationship between pinna anthropometric parameters and simulated PRTFs, contributing to a deeper understanding of the acoustic characteristics of the pinna and its role in sound localization.

Methods

Model acquisition

Participants

A total of 75 participants, aged 24 ± 5 years, were recruited for this research, including 40 males and 35 females. All participants were in good physical health, without any physiological abnormalities of the pinna, and were instructed to refrain from wearing earrings during the experimental scanning process. Participants with long hair were required to use hair clips, caps, or other auxiliary tools to secure their hair, preventing it from obstructing the pinna and affecting the scanning results. The recruitment was conducted at Tianjin University, and all participants were students recruited via internal advertisements. This study has been approved by the Tianjin University Ethics Committee for conduct and data sharing (approval number: TJUE-2024-462). Informed consent was obtained from all participants for the anonymous publication of the 3D scanning data and acoustic simulation results.

3D scan

The dataset was acquired using a handheld, non-contact 3D laser scanning system, specifically the HSCAN-S scanner from Thunk3D (Beijing Xunheng Technology Co., Ltd.), with a resolution of 0.1 mm. The scanner’s initial position was adjusted according to the participant’s head orientation to mitigate the impact of the scanner’s position and orientation on the accuracy of pinna models. The handheld scanner was maintained in a vertical orientation during initial alignment, with the positioning laser precisely aligned to the concha area. During the scanning, participants were required to maintain an upright sitting posture and minimize head movement. The scanning procedure is detailed in Fig. 1.

The scanning procedure for acquiring three-dimensional pinna models. Steps A and B are the calibration before scanning and the scanning process. Step C is the spatial point cloud acquired from scanning. Steps D and E merge and automatically repair the point cloud. After confirming that the merged and repaired model meets the requirements, Step F is executed to save it in STL format.

Given the complex geometric characteristics of the pinna, each pinna was scanned from multiple angles, with the scanner moving slowly throughout the process to ensure comprehensive data capture. The scanning time was approximately 5 minutes per pinna. Participants were briefed on the scanning procedure, including the presence of flashing lights, and instructed to keep their eyes closed during scanning. Additionally, they were assured that they could take a break or terminate the procedure at any time if they felt uncomfortable. After scanning one pinna, participants repositioned to facilitate scanning of the contralateral pinna. Multiple scans were merged, and a point cloud was extracted using the system’s post-processing software, automatically generating a 3D model with 0.1 mm resolution, as shown in Fig. 1.

Post-processing

Magics software was utilized for specialized 3D modeling post-scanning, focusing on defect correction and model optimization to address image noise and problematic triangular mesh features. The technical workflow and repair steps are summarized in Fig. 2.

Workflow for pinna model repair. There are three main procedures: hole filling, surface smoothing, and solidification. Among them, when the scanning system merges the point cloud, sharp protrusions may occasionally be generated due to misjudgment. In such cases, these protrusions must be manually filtered and treated as holes for filling.

The standardized repair process is as follows:

-

1.

Eliminate interfering shells generated during scanning and reconstruction, and perform normal correction on-pinna models with inverted normal.

-

2.

Manually repair defective areas of the model through operations such as creating bridges and triangular faces until no holes or missing parts remain.

-

3.

Employ software filters like sharp feature removal and duplicate face removal to repair problematic triangular meshes and eliminate geometric distortion.

-

4.

Smooth the pinna model by performing localized smoothing operations to remove surface noise and identify and mark small triangular cones on feature regions such as the external auditory canal entrance, triangular fossa, concha, and helix edge for targeted elimination and hole-filling repair.

-

5.

Simplify the pinna model using triangle reduction operations by setting parameters such as minimum detail, maximum angle, and iteration count to reduce the number of triangular faces while preserving the geometric topological structure, thereby improving computational efficiency.

-

6.

If necessary, check for any remaining surface irregularities and perform additional smoothing, ultimately completing the geometric model repair.

COMSOL Multiphysics simulation software was employed to control and validate the quality of the optimized pinna models obtained after the repair process shown in Fig. 2. The processed models were imported into COMSOL to assess their suitability for acoustic simulation. The model surface smoothness and overall geometry were thoroughly examined during this step. The imported models were rigorously inspected for artifacts, discontinuities, or irregularities that could compromise the accuracy of acoustic simulations, focusing on any sharp triangular edges or surface inconsistencies. The software’s visualization tools enabled rotation and zooming of the models, ensuring a comprehensive evaluation of all surface details.

Additionally, preliminary acoustic simulations were performed to verify that the models could successfully generate valid results without numerical instabilities or mesh-related errors. This validation confirmed the models’ visual quality and functional adequacy for advanced acoustic analyses. Models meeting the criteria for surface smoothness and simulation compatibility were deemed suitable for further acoustic studies, while those requiring additional refinement underwent further optimization steps. The three-dimensional pinna models of all subjects were refined based on this process.

Computational processing

Anthropometric parameter measurement

Following the acquisition and optimization of three-dimensional pinna models, the next crucial phase involved the precise measurement and analysis of pinna morphological parameters. This step aimed to provide a quantitative understanding of the geometric characteristics of the pinna, thereby providing a basis for subsequent acoustic analysis and the development of individualized PRTF models. The morphological features of the pinna could be comprehensively captured by integrating high-quality 3D models with rigorous parameter measurements, thus facilitating the establishment of potential correlations between morphology and acoustic performance.

A comprehensive morphological analysis of 150 pinna samples was performed using Magics software, with a measurement resolution of 0.01 mm. The parameter selection adhered to the national standard ISO 14738:2002 (Safety of machinery Anthropometric requirements for the design of workstations at machinery) and incorporated commonly used pinna measurement indicators from relevant literature12,13,14,15. 20 key anthropometric parameters were selected for precise measurement, as listed in Table 1, explicitly referring to previous studies to guide the selection. The specific meanings of the 20 anthropometric parameters are shown in Fig. 3.

Anthropometric parameters. The red labels represent parameters related to the height of the pinna, the blue labels represent parameters related to the width of the pinna, the yellow labels correspond to the depth-related parameters of the cross-section of the pinna, and the black labels indicate the angular parameters of the pinna.

All measurements were performed using Materialise Magics software to ensure accuracy and reliability. Specifically, distances were determined using the point-to-point method, while angles were measured using the three-point plane method. The measurement method based on Magics is shown in Fig. 4. For the parameters d2, d3, d4, d5, d6, d7, d9, d10, d11, d12, and d16, distances were measured in the top view using the 2D X-Y plane. Parameters d13 and d14 were measured in the right view using the 2D Y-Z plane. The distance for d1 was measured along the X-axis in the top view, d8 along the Y-axis, and d15 along the Z-axis in the right view. Angles θ1 and θ2 were measured in the 2D X-Y plane in the top view, while θ3 and θ4 were measured in the 2D Y-Z plane in the right view.

Method for measuring anthropometric parameters. When measuring, the coordinate axis of the model is shown in the lower right corner of the subfigure. The light green plane is the 2D X-Y plane, the red annotation in the plane indicates the distance parameter and the black annotation indicates the angle annotation. Three different measurement methods are shown in the three subfigures: (a) Distance parameters aligned with the X-axis in the 2D X-Y plane; (b) Distance parameters measured in the 2D X-Y plane; (c) Angle parameters measured in the 2D X-Y plane. (The subfigures show the measurements of d1, d2, and θ1, respectively).

Following the measurement process, three independent measurements were taken for each parameter, and the mean value was used for subsequent analyses to reduce random errors and enhance data stability.

Acoustic simulation

The precise data served as the foundation for acoustic simulation and PRTF acquisition following the processing of pinna models and measurement of physiological parameters. The PRTF, which describes how sound is transformed as it interacts with the pinna’s unique geometry, was calculated to represent its acoustic characteristics accurately.

The PRTF is mathematically expressed as follows:

where PRTF(f,θ) is the Pinna-Related Transfer Function at frequency f and lateral angle θ. The PRTF is represented using an interaural-polar coordinate system, where θ represents the lateral angle relative to the forward direction. Pout(f,θ) represents the sound pressure measured at the ear canal entrance after interacting with the pinna’s geometry. Pin(f) represents the sound pressure of the incident sound source before interacting with the pinna. This formula establishes a direct relationship between the incident sound and the modified sound after interacting with the pinna, enabling the simulation of how individual pinna geometries influence sound perception. Highly accurate and individualized simulations of acoustic behavior can be achieved by using personalized 3D pinna models in combination with this PRTF.

The BEM was employed to simulate and analyze the acoustic characteristics of the pinna model in a sound field. The geometric structure of the pinna model was reconstructed using high-precision three-dimensional scanning data. The material parameters were based on anatomically measured data of ear tissue16,17,18, and their default values were predefined by COMSOL’s built-in physiological human ear impedance model (Outward Human Ear Radiation).

The mesh discretization employs triangular elements with edge lengths set to 1/6 of the wavelength corresponding to the respective frequency range to enhance the accuracy of acoustic simulations19. This adjustment is particularly critical in the high-frequency range, where a smaller edge length allows for a more precise capture of wavefront details. A convergence analysis was performed to ensure simulation accuracy, leading to the selection of an average edge length of 1 mm for high frequencies. This configuration achieves an optimal balance between computational accuracy and resource efficiency, enabling high-quality simulations while effectively managing computational demands. Furthermore, the pinna model was extended to include some of the surrounding head areas for the calculation of PRTFs to make it more closely match experimental conditions.

The sound source was configured as a point source, with a frequency range from 200 Hz to 20 kHz, covering the entire human audible spectrum. According to the reciprocity principle, the sound source was placed at the entrance of the pinna’s ear canal, while the receivers were positioned at fixed lateral angles (left + 90° and right −90°) in the interaural-polar coordinate system with a near-field distance of 3 cm and a far-field distance of 1 m6,11. In the interaural-polar coordinate system, 0° corresponds to the frontal direction relative to the listener’s head. The sound pressure level was set at 1 Pa to simulate the incident wave under free-field conditions. The pinna’s physiological impedance was modeled using COMSOL’s built-in Human Ear model, allowing for accurate simulation of the pinna’s response to sound waves across different frequencies. In contrast, other geometric surfaces were set as soft sound field boundaries to avoid interference from reflected waves, ensuring that the sound field propagation characteristics accurately reflect the acoustic behavior of the pinna. With these settings, the acoustic behavior of the pinna in the sound field could be simulated accurately.

PRTF acquisition

According to the simulation setup method, the 75 pairs of pinna models were individually imported into COMSOL for acoustic simulation calculations. Each calculation standardized the position coordinates of the pinna model, excitation sound source, and receiver to ensure the relevant transfer function for each pinna was calculated under identical conditions. The simulation employed pressure acoustics, boundary elements, pressure acoustics, and frequency domain physics interfaces for modeling.

After the computation was completed, a point result plot of the pabe.Lp expression was generated, and the frequency-sound pressure data of the receivers was exported. The simulation results were all saved in CSV format. A standard pinna model was selected for multiple simulations to verify the accuracy of the simulation process, with consistency ensured through the comparison of the transfer functions from multiple simulations. Additionally, the results were processed and exported using the pabe.p_t expression and converted into SOFA format files for standardized data sharing and analysis.

Data Records

Overview

The complete data records were stored in the figshare repository and were freely available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28545548.v120. The repository structure is illustrated in Fig. 5.

Notional illustration of the folder structure of the data repository. At the top level, there are two main folders: Source (dark blue box) and Results (dark green box). The Source folder contains two subfolders: Model Dataset and Simulation Dataset. The Model Dataset folder includes the original and BEM models, while the Simulation Dataset folder contains the COMSOL files and parameter setting files. The Results folder also contains two subfolders: PRTF Results and Measurement Results. The PRTF Results folder includes the SOFA files and results of the PRTFs, and the Measurement Results folder contains the parameter results.

These additional data allowed for more refined acoustic analyses, particularly in simulations requiring high accuracy across various frequency ranges. The combination of geometric detail and simulation-ready models made this dataset a valuable resource for studies on how pinna shape influences acoustic properties, thereby contributing to advancements in auditory perception research and personalized hearing solutions.

Model data

A total of 150 pinna models were created in the Original models folder, and 3 left pinna models were selected for presentation. These pinna models have been post-processed, with smooth surfaces, and have been solidified. All models have been imported into COMSOL for testing to ensure they can be used for acoustic simulations directly. Since the scanners started scanning in an initial state perpendicular to the ground during scanning, the coordinate axis directions of all pinna models were unified. Furthermore, the origin of the coordinate axis was uniformly set at the center of the ear canal entrance for each pinna to facilitate the setting of the sound source excitation for acoustic simulation.

The model could more accurately capture acoustic behavior across the spectrum by adapting the mesh to various frequency ranges. Specifically, it was performed with target edge lengths of 10 and 5 mm, in the frequency bands [0.2, 0.5 kHz] and [0.5, 2.0 kHz], respectively. At higher frequencies, edge lengths of 2 mm and 1 mm were applied for the frequency bands [2.0, 8.0 kHz] and [8.0, 20 kHz], respectively. According to the 4 frequency ranges, the dataset provided example boundary element models with edge lengths of 10 mm, 5 mm, 2 mm, and 1 mm, as shown in Fig. 6, to meet different simulation requirements. The subdivision of the edge length was always maintained at 1/6 of the source wavelength to ensure high-precision PRTF data was obtained during computation. These BEM models with different edge lengths were placed in the BEM Models folder as separate zip files.

Simulation data

The simulation dataset included two parts: COMSOL files and global parameters. The global parameters were provided in txt file format and could be directly imported into the global definitions in COMSOL. These global parameters included tissue sound speed, maximum frequency, wavelength, etc., providing the simulation configuration information.

The COMSOL files contained specific pinna models, material settings, and sound pressure results. Users could directly open these files to view and analyze the simulation results of the sound field without needing to repeat the calculations. These COMSOL files covered various conditions, including mesh subdivisions, source positions, and frequencies, providing rich data support for sound field modeling research.

By providing these two parts, this dataset aimed to provide comprehensive data support for hearing-related sound field modeling research, including necessary parameter inputs and calculation result outputs, enabling researchers to conduct analysis and application work efficiently.

PRTF data

The PRTF Data files contained two CSV files. One zip file included 150 PRTF simulation calculation results covering near- and far-field conditions. The other zip file contained the locations of the peaks and notches in these 150 PRTF data sets. As for the PRTF calculation results, due to the simulation research setting with a frequency range of 200 Hz to 20 kHz and a resolution of 100 Hz, a total of 150 (individuals) × 198 (frequency points) × 2 (distances) × 2 (ears) data sets were obtained, with each set containing the sound frequency and corresponding sound pressure value. The data for the near-field and far-field conditions were stored in separate sheets.

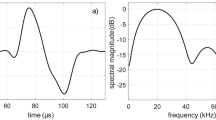

The curves plotted based on the PRTF calculation data are shown in Fig. 7. Relevant research has demonstrated that the information on peaks and notches in the PRTF curve is crucial for human auditory localization. Generally, the PRTF curve contained seven main features: P1, N1, P2, N2, P3, N3, and P4. However, a few individuals only have six features, lacking P4, which is annotated in the CSV file. Among them, the five features P1, N1, P2, N2, and P3 significantly impact spatial localization6,21,22.

Frequency Response Curve of PRTF (θ = ± 90°, Δf = 100 Hz). The PRTF spectral curve is plotted from the 3 cm near-field results, aiming to present the peaks and notches more clearly. The locations of the peaks (P) and notches (N) are marked on the curve. However, it is worth noting that some PRTF curves lack the P4 component due to individual differences.

Statistical analysis showed no significant difference between male and female PRTFs at P and N frequencies, with an average difference in magnitude of less than 1 dB. Furthermore, related research has shown that the physiological structure of the adult pinna remains relatively stable within the age range of 30 to 50 years10. As the pinna shape is the most important factor in determining PRTF, and this dataset includes a variety of pinna structures, it could meet the research needs.

Technical Validation

Model data

Through point cloud registration synthesis and semantic mapping, the resulting number of triangular faces averages 236,730, where a facet was defined as going from one mesh to another unchanged mesh. After the repair process shown in Fig. 2, the number of triangular facets for the realized pinna model averages 6,930. The literature mentions that the dataset contained around 54,530 triangular facets11. Therefore, the pinna models obtained through structured light scanning could accurately reproduce the physiological morphological structural features of the pinna, meeting the requirements for personalized research.

Although the optimized model had fewer triangular facets than the models in the literature, this dataset handled the edges more smoothly and naturally, better reflecting the inherent characteristics of the pinna. More importantly, fewer triangular facets imply a higher simulation computation speed, which could greatly improve the efficiency of acoustic simulations.

Measurement data

A comprehensive statistical analysis of all parameters was performed once the data collection was complete. Initially, each parameter was standardized to ensure comparability across different scales. The Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests were then employed to assess the normality of distribution for each parameter. The results indicated that all 20 parameters conformed to a normal distribution, as illustrated by the violin plots in Fig. 8. These plots effectively demonstrated the data’s adherence to a normal distribution, providing a solid foundation for subsequent analyses.

Statistical distribution of standardized anthropometric parameters. Each parameter was standardized, and then normality tests were conducted for some parameters, such as d3, d7, and d15. Two density peaks appeared, possibly caused by the morphological differences between males and females in these parameters12.

Each pinna model underwent meticulous post-processing to ensure precise geometric accuracy and smooth surface contours. Subsequently, 20 anthropometric parameters were measured for each pinna, and their statistical results were analyzed. Following normality tests (such as the Shapiro-Wilk test), it was found that all 20 anthropometric parameters conformed to a normal distribution, laying a solid foundation for further statistical analysis.

Additionally, the anthropometric parameters were measured directly to compare and verify the accuracy of the parameters obtained through Magics. The parameters d2, d6, d7, d9, d11, and d15 were used for accuracy verification. Each parameter was measured three times, and the average value was taken, accurate to 0.5 mm. The software measurement results, the actual measurement results, and the percentage errors are shown in Table 2. As can be seen, all percentage errors are less than 1.5%, demonstrating that the measurement method of this dataset is reliable in terms of accuracy. Furthermore, the precision of the software measurement results is 0.01 mm, providing a more accurate reflection of anthropometric results.

The pinna parameter dataset meets the requirements of accuracy and representativeness after measurement verification. It can reflect the physiological characteristics of the pinna relatively precisely and conforms to the auricular morphology of most populations. Therefore, the database lays a solid foundation for acoustic analyses and provides valuable reference material for research in related fields.

PRTF data

The dataset employed actual measurement methods for validation to verify the accuracy of the 150 sets of pinna-related transfer function data obtained through simulation. The experiments were conducted in an anechoic chamber to minimize the impact of environmental noise. Five subjects were randomly selected from a pool of 75 participants to ensure the sample was representative. The measurements were performed using a AKG C111 LP model miniature microphone with a frequency response range of 60 Hz to 15 kHz (typical frequency response fluctuation: ± 3 dB), at a sampling frequency of 44.1 kHz for both the microphone and speaker. This range ensures the accuracy of the measurement data. The microphone was rigorously calibrated before the experiment.

In alignment with the auditory environment conditions set in the simulation, a white noise signal source encompassing the entire frequency range was played at both near-field and far-field distances from the subject’s ear. The 1-meter far-field measurement results were selected to facilitate verification. A miniature microphone was positioned at the entrance of the subject’s ear canal to capture the actual measurements, thereby obtaining the pinna-related transfer function data. The setup of the microphone placement and the experimental environment is shown in Fig. 9.

Experimental measurement methods and microphone placement. The left one shows the overall scene of the actual measurement experiment. The miniature microphone is connected to the experimental computer to record the time-domain audio signal, and the speaker can be precisely adjusted on a 1 m rail track. The right one illustrates the placement of the miniature microphone, which is ensured to be at the entrance of the participant’s external auditory canal before recording.

Subsequently, the time-domain signals obtained from the measurements and simulations were transformed into the frequency domain using the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to facilitate comparison. The FFT is a widely used algorithm to compute the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) of a sequence and its inverse, which can be mathematically expressed as:

where X(k) represents the frequency component at index k, x(n) is the input signal at time index n, and N is the total number of samples.

Empirical measurements were conducted to validate the accuracy of the 150 sets of pinna-related transfer function data obtained through simulations. Tests were performed on the left and right ears of 5 individuals selected from a pool of 75 subjects in an anechoic chamber. To facilitate a valid comparison with the measured data obtained from these 5 participants, the simulations corresponding to these individuals were recalculated with an increased highest frequency of 22.05 kHz, enabling appropriate resampling of the simulated impulse response data, thereby allowing for a valid comparison between measurement and calculation. The setup ensured that the relative position between the sound source and the subject’s pinna matched the simulation conditions. The measured impulse response data were processed and transformed into frequency-domain transfer functions. Following the transformation, waveform analyses were conducted on the measured data and the data obtained from simulation calculations. The validation process, including the comparison between simulation and measured results, is shown in Fig. 10.

The results of the analysis comparing the averaged frequency-domain data from the left and right ears were consistent with the simulation results. Figure 11 compares the measured and simulated average data for both ears. The waveforms of the measured data were highly similar to the simulation results.

Root mean square error (RMSE) and log-spectral distance (LSD) were used as metrics for quantitative analysis to compare the degree of discrepancy between the two datasets. RMSE quantifies the average deviation between the simulation and measurement data points, measuring the overall error magnitude. LSD, on the other hand, evaluates the spectral differences between the two datasets, offering an analysis of their frequency-domain similarity. The accuracy of the simulation in reproducing the pinna-related transfer function was comprehensively evaluated by analyzing these two metrics, as shown in Fig. 12.

RMSE and LSD for the Evaluation of 5 Sets of Results. The blue represents the RMSE or LSD of the left ear, while the orange represents the RMSE or LSD of the right ear. The results indicate a strong correlation between the simulation and experimental data, with both RMSE and LSD values being relatively low. Specifically, RMSE ranged from 3 to 5 dB, and LSD ranged from 0.05 to 0.75.

Notably, Subject 1 exhibited relatively higher RMSE and LSD values for the left ear, which may be attributed to morphological differences between the left and right ears of this subject and errors introduced during model repair. The evaluation confirms the reliability of the simulation model in predicting the acoustic response of the pinna.

It is important to note that the PRTF simulation results in this study were obtained under free-field conditions and may not be fully applicable to situations involving headphones that create a closed acoustic field. Although the pinna model used for simulation includes the pinna and a baffle, the influence of the head was reduced to facilitate future research on PRTF in closed sound fields. The validation method inherently possesses certain limitations, so adopting 3D-printed artificial ears for more accurate comparisons could be considered. In addition, the pinna model with a closed ear canal was used during the simulation due to the scanner’s inability to capture the ear canal. COMSOL’s built-in physiological impedance model was utilized to set the boundary conditions, which approximates the ear canal’s effects on the sound field. Since the geometric shape of the ear canal was not explicitly modeled, medical imaging is planned to reconstruct the external ear canal and tympanic membrane and integrate them with the pinna model to improve the accuracy of the PRTF results. The study primarily focused on the relationship between the shape structure of the pinna and its corresponding PRTF variations, and thus a single sound source direction was employed, while the characteristics of multiple sound source directions were not considered. The influence of multiple sound source directions is planned to be systematically investigated in future work. Furthermore, variations in microphone sensitivity, microphone size, and the shielding effectiveness of the anechoic chamber can all affect the accuracy of the measurement results.

Code availability

The original data allows researchers to tailor the processing workflow for their specific applications using software of their choice, while the post-processed data allows consumers to employ the data without reprocessing it directly. All data is publicly available and can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28545548.v120. The original data supporting the results of this study are available from the corresponding authors.

References

Langendijk, E. H. A. & Bronkhorst, A. W. Contribution of spectral cues to human sound localization. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 112, 1583–1596, https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1501901 (2002).

Raykar, V. C., Duraiswami, R. & Yegnanarayana, B. Extracting the frequencies of the pinna spectral notches in measured head related impulse responses. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 118(1), 364–374 (2004).

Bomhardt, R., de la Fuente Klein, M. & Fels, J. A high-resolution head-related transfer function and three-dimensional ear model database. Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics 29, https://doi.org/10.1121/2.0000467 (2017).

Pollack, K., Majdak, P. & Furtado, H. Application of non-rigid registration to photogrammetrically reconstructed pinna point clouds for the calculation of personalised head-related transfer functions. Hamburg (2023).

Braren, H. S. & Fels, J. Towards Child-Appropriate Virtual Acoustic Environments: A Database of High-Resolution HRTF Measurements and 3D-Scans of Children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, 324 (2022).

Mokhtari, P., Takemoto, H., Nishimura, R. & Kato, H. in Proceedings of the 20th International Congress on Acoustics (ICA’10), Sydney, Australia (2010).

Joshi, M., Gupta, N. & Hmurcik, L. Modeling of pinna related transfer functions (prtf) using the finite element method (FEM). in COMSOL conference (2013).

Gumerov, N. A., O’Donovan, A. E., Duraiswami, R. & Zotkin, D. N. Computation of the head-related transfer function via the fast multipole accelerated boundary element method and its spherical harmonic representation. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 127, 370–386, https://doi.org/10.1121/1.3257598 (2010).

Kahana, Y. & Nelson, P. A. Boundary element simulations of the transfer function of human heads and baffled pinnae using accurate geometric models. Journal of Sound and Vibration 300, 552–579, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2006.06.079 (2007).

Engel, I. et al. The SONICOM HRTF Dataset. Journal of the Audio Engineering Society 71, 241–253, https://doi.org/10.17743/jaes.2022.0066 (2023).

Guezenoc, C. & Séguier, R. A wide dataset of ear shapes and pinna-related transfer functions generated by random ear drawings. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 147, 4087–4096, https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0001461 (2020).

Fan, H. et al. Anthropometric characteristics and product categorization of Chinese auricles for ergonomic design. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 69, 118–141, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2018.11.002 (2019).

Iida, K., Shimazaki, H. & Oota, M. Generation of the amplitude spectra of the individual head-related transfer functions in the upper median plane based on the anthropometry of the listener’s pinnae. Applied Acoustics 155, 280–285, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2019.06.007 (2019).

Guo, Z. et al. Anthropometric-based clustering of pinnae and its application in personalizing HRTFs. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 81, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2020.103076 (2021).

Stitt, P. & Katz, B. F. G. Sensitivity analysis of pinna morphology on head-related transfer functions simulated via a parametric pinna model. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 149, 2559–2572, https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0004128 (2021).

Hudde, H. & Engel, A. Measuring and Modeling Basic Properties of the Human Middle Ear and Ear Canal. Part I: Model Structure and Measuring Techniques. Acta Acustica United with Acustica 84, 720–738 (1998).

Hudde, H. & Engel, A. Measuring and Modeling Basic Properties of the Human Middle Ear and Ear Canal. Part II: Ear Canal, Middle Ear Cavities, Eardrum, and Ossicles. Acta Acustica united with Acustica 84, 894–913 (1998).

Hudde, H. & Engel, A. Measuring and Modeling Basic Properties of the Human Middle Ear and Ear Canal. Part III: Eardrum Impedances, Transfer Functions and Model Calculations. Acta Acustica united with Acustica 84, 1091–1108 (1998).

Ziegelwanger, H., Kreuzer, W. & Majdak, P. A priori mesh grading for the numerical calculation of the head-related transfer functions. Applied Acoustics 114, 99–110, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2016.07.005 (2016).

Liu, J. & Liu, H. PRTF-Nislab. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28545548.v1 (2025).

Iida, K. & Ishii, Y. Effects of adding a spectral peak generated by the second pinna resonance to a parametric model of head-related transfer functions on upper median plane sound localization. Applied Acoustics 129, 239–247, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2017.08.001 (2018).

Luan, Y., Doutres, O., Nélisse, H. & Sgard, F. Experimental study of earplug noise reduction of a double hearing protector on an acoustic test fixture. Applied Acoustics 176, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2020.107856 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank everyone who participated in this study and cooperated with us by following the instructions provided. This work was supported by projects from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2023YFF1203500).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jihan Liu: Methodology, Software, Validation, Data curation, Writing-original draft, Writing—review and editing. Hongxing Liu: Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Writing—review and editing. Jianing Zhu: Methodology. Xu Han: Software. Yanru Bai: Methodology, Writing—review and editing. Guangjian Ni: Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing, Supervision. Dong Ming: Conceptualization, review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Liu, H., Zhu, J. et al. A Dataset of Pinna-Related Transfer Functions Using High-Resolution Pinna Models. Sci Data 12, 992 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05334-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05334-9