Abstract

Dual water isotopes (δ¹⁸O, δ²H, referred to as δD) serve as robust tracers for water masses, enabling the identification and quantification of ocean currents and circulation patterns, thereby complementing traditional temperature-salinity and velocity metrics. This study presents a comprehensive dual water isotope dataset covering the northern South China Sea (SCS) to quantify summer water mass transport, addressing the scarcity of isotope observations in this region. The dataset comprises 873 dual isotope samples collected from 169 stations during summer (2015–2021), covering depths of 0–3700 m. Core parameters include δ¹⁸O, δD, temperature, and salinity. Additionally, using uniform end-member selection criteria and an isotope correction method, we applied the SIAR isotope mixing model to quantify the contributions of distinct water masses and characterize circulation features. This dataset fills a critical gap in SCS isotope data and establishes a standardized methodology for quantitatively interpreting water mass transport using dual water isotopes, underscoring the significance of isotopes as supplementary indicators for monitoring ocean currents and circulation dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Craig and Gordon1 (1965) were the first to propose the application of stable isotope analysis of seawater (δ¹⁸O, δ²H, referred to as δD) as tracers for water masses and global hydrological cycles. These water isotopes are influenced by processes such as evaporation, precipitation, runoff, high-salinity water intrusion, and sea ice formation1,2,3. Consequently, distinct dual water isotope signatures have been identified across different oceanic regions globally4,5,6,7,8. Additionally, vertical profiles of water masses exhibit unique isotopic characteristics9,10,11, providing a theoretical foundation for quantifying water mass transport and ocean current dynamics.

To date, stable seawater isotopes have been employed to validate ocean circulation models and characterize processes governing spatial variability12. Furthermore, they have been used to infer control information on oxygen isotope ratios in calcareous plankton shells, enabling reconstructions of paleo-ocean salinity and circulation patterns13. The NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) Global Seawater Oxygen-18 Database has compiled and homogenized most pre-1998 isotope data14. Since 1998, the isotopic platform facility at LOCEAN (CISE-LOCEAN) has expanded global coverage by analyzing water isotope samples from the North Atlantic, equatorial Pacific, Atlantic, South Indian Ocean, and Southern Ocean15, regions previously underrepresented in the GISS database14. Although the LOCEAN dataset spans 1998–2021 and continues to grow, it lacks comprehensive coverage of the South China Sea (SCS), particularly the northern SCS (NSCS), where dynamic oceanographic processes dominate. This highlights the urgent need to establish a dedicated isotope dataset encompassing surface-to-bottom layers in the NSCS.

The combined use of hydrogen-oxygen isotopes and the SIAR (Stable Isotope Analysis in R) isotope mixing model has been successfully applied in diverse contexts, including nearshore estuaries and quantitative assessments of typhoon-induced upwelling16,17. Traditional approaches rely on extensive cruise-based temperature-salinity and velocity measurements to characterize NSCS currents18. However, these methods often fail to fully resolve contributions from distinct water masses, such as coastal waters. In contrast, water isotopes act as intrinsic fingerprints of water masses, encapsulating cumulative signatures of long-term hydrographic interactions17. Even in coastal regions with multiple freshwater sources and homogenized low salinity, isotopes provide a novel perspective for tracing water mass origins19,20. Wang et al.21 further investigated summer circulation in the NSCS using a 3D numerical model. While model outputs offer spatially continuous data, their accuracy is constrained by resolution limitations and nonlinear complexities. Isotope-based methods, when integrated with mixing models, thus serve as a complementary quantitative tool to enhance monitoring capabilities for ocean circulation.

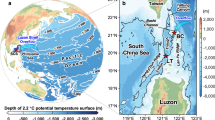

The shelf and slope circulation in the NSCS is highly complex and variable, driven by seasonal monsoon reversals, water exchange with the Northwest Pacific through the Luzon Strait, and intricate topography22. Although prior studies have partially characterized shelf and slope currents18,21,23, critical gaps remain in understanding: (1) dynamic linkages and material exchange between the SCS basin-scale circulation and shelf currents, (2) cross-slope transport mechanisms in the NSCS, and (3) the influence of terrestrial runoff and coastal currents on regional circulation. This study seeks to advance understanding of these gaps by compiling and augmenting a comprehensive dual-isotope dataset covering the NSCS during summer, providing a foundational resource for investigating unresolved questions. Utilizing unified end-member selection criteria, an isotope correction method, and an isotope mixing model, we generate a quantitative dataset to resolve circulation-driven transport processes, including the impacts of freshwater plumes, coastal water contributions, and cross-shelf exchanges between the SCS basin and shelf regions.

Methods

Sample collection and storage

The EH (Eastern Hainan Island) cruise comprised three transects conducted in September 2015 within the eastern Hainan Island upwelling region. Seawater samples were collected using a rosette sampler equipped with Niskin bottles. To minimize post-sampling biological processes that could alter water isotope signatures, the collected water was filtered through 0.45 μm pore-size cellulose acetate membranes and transferred into pre-cleaned 100 mL high-density polyethylene (HDPE) bottles. To reduce bioavailability and prevent evaporation-induced isotopic fractionation, the bottle caps were tightly sealed and secured with Parafilm (PM-996; country of origin: USA) wrapped around the cap interface. Samples were then stored at −20 °C in a freezer and transported to a land-based laboratory for isotopic analysis. Full-depth profiles of temperature, salinity, and depth were concurrently measured using a calibrated SBE 911plus CTD unit (Sea-Bird Electronics, Inc., USA). Sampling details and references for cruises other than EH are summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 1a.

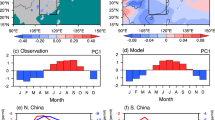

Study area and sampling information in the northern South China Sea. (a) Topographic distribution and sampling regions from different cruises. (b) Number of sampling layers per station. c Maximum sampling depth at each station. Abbreviations: EH (Eastern Hainan), LZ (Luzon Strait), NBBG (Northern Beibu Gulf), PRE (Pearl River Estuary), SBBG (Southern Beibu Gulf), WG (Western Guangdong Province).

Isotopic measurements

For hydrogen isotope analysis, 200 μL of seawater was aliquoted into a 12 mL Labco Exetainer® vial containing a hydrophobic platinum catalyst rod. The vial was tightly sealed, and a mixed gas of hydrogen (2% by volume) and helium was injected to initiate equilibrium exchange between the water sample and hydrogen gas under platinum catalysis. After 40 minutes of equilibration, the isotopic composition of the hydrogen gas was analyzed using a Gasbench II coupled to an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Gasbench II-IRMS; Thermo Scientific). Isotopic values were calibrated against reference materials provided by the United States Geological Survey (USGS): USGS47 (δDV-SMOW = −150.2‰), USGS45 (δDV-SMOW = −10.3‰), USGS48 (δDV-SMOW = −2.0‰), and USGS50 (δDV-SMOW = + 32.8‰). Analytical precision was ± 0.5‰ (n = 8), with an accuracy of −2.0 ± 0.5‰ (n = 8, USGS48).

The δD value, expressed relative to the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW), was calculated as:

where RV-SMOW is the D/H ratio of VSMOW, and Rsample is the D/H ratio of the sample. The final δD values had an analytical precision of ±0.5‰.

For oxygen isotope analysis, 200 μL of seawater was transferred into a 12 mL Labco Exetainer® vial. A mixed gas of carbon dioxide (1% by volume) and helium was injected to initiate equilibrium exchange between the water sample and CO2. After 24 hours of equilibration, the isotopic composition of CO2 was analyzed using the Gasbench II-IRMS system, following protocols described in Lao et al.16,17. Calibration was performed using USGS reference materials: USGS47 (δ¹⁸OV-SMOW = −19.8‰), USGS45 (δ¹⁸OV-SMOW = −2.2‰), USGS48 (δ¹⁸OV-SMOW = −2.2‰), and USGS50 (δ¹⁸OV-SMOW = + 5.0‰) (IAEA). Analytical precision was ± 0.1‰ (n = 8), with an accuracy of −2.2 ± 0.1‰ (n = 8, USGS48).

The δ¹⁸O value, normalized to VSMOW, was calculated as:

where Rsample is the 18O/16O ratio of the sample and RV-SMOW is the 18O/16O ratio of VSMOW. The δ¹⁸O values had an analytical precision of ±0.1‰. Deuterium excess, defined as d-excess = δD−8 × δ¹⁸O, serves as an indicator of kinetic fractionation associated with phase changes and inversely correlates with δ¹⁸O during evaporation processes24.

Stable isotope mixing model

The proportional contributions of distinct water masses can be quantified using a Bayesian stable isotope mixing model, implemented via the Stable Isotope Analysis in R (SIAR) package (SIAR v4.2, R v4.1.1). The general framework of the model is defined as follows:

Here, Xij denotes the j-th isotopic observation at the i-th mixed sample. \({s}_{{jk}}\) represents the j-th isotopic value of the k-th source, modeled as a normal distribution with mean \({\mu }_{{jk}}\) and variance \({\omega }_{{jk}}^{2}\). \({c}_{{jk}}\) is the fractionation factor for the j-th isotope in the k-th source, characterized by mean \({\lambda }_{{jk}}\) and variance \({\tau }_{{jk}}^{2}\). pk denotes the proportional contribution of source k, estimated by the SIAR model. \({q}_{{jk}}\) corresponds to the concentration of the j-th isotope in the k-th source. \({{\varepsilon }}_{{ij}}\) represents residual variance unexplained by the model, following a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance \({\sigma }_{j}^{2}\), where \({\sigma }_{j}^{2}\) is inferred during model calibration.

The Bayesian framework allows incorporation of prior information to refine the precision of contribution estimates25. Priors may be uninformative (vague) or informative, depending on existing knowledge of water mass mixing. The natural prior distribution for \({p}_{k}\) is the Dirichlet distribution, a multivariate generalization of the Beta distribution. The Dirichlet prior assumes independence among sources while constraining their summed contributions to unity. In SIAR, users can specify prior mean proportions (summing to 1) for each source and the standard deviation of the first proportion to derive parameters \({\rm{{\rm K}}}\) and \({\rm{\alpha }}\). However, the Dirichlet prior does not permit individual uncertainty specifications for each proportion. In this study, an uninformative prior assuming equal proportions was adopted.

Marginal distributions generated by the Dirichlet distribution with parameters \({\rm K}\) and \(\alpha \) are defined as:

Distributional properties are further described by:

where \({p}_{k}\) and \({p}_{p}\) (with Dirichlet parameters \({\alpha }_{k}\) and \({\alpha }_{p}\)) denote the proportional contributions of the k-th and p-th sources, respectively. The default SIAR configuration sets all \({\rm{\alpha }}\) values to 1, corresponding to an uninformative prior with equal mean contributions (\(1/{\rm{{\rm K}}}\)) and variance \(\left({\rm{{\rm K}}}-1\right)/({{\rm{{\rm K}}}}^{2}\left({\rm{{\rm K}}}+1\right))\). This study employs the default uninformative Dirichlet prior, ensuring that results are predominantly data-driven. Model fitting proceeds via Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulations to generate posterior distributions of \({p}_{k}\) consistent with observations.

The SIAR framework has been widely validated for quantifying source contributions in stable isotope studies26,27. Due to their conservative behavior and minimal alteration by biogeochemical processes, water isotopes (δ¹⁸O and δD) are robust tracers of hydrological cycling1,6,17,24. Furthermore, distinct isotopic signatures among water masses enable successful applications in tracing proportional contributions and circulation features8,10,17,28.

Correction of water isotopes affected by kinetic fractionation

It is noteworthy that incorporating accurate fractionation factors into the SIAR model can eliminate the need for explicit corrections. Previous studies have estimated fractionation factors for water isotopes, primarily linked to temperature and atmospheric humidity24. However, a critical limitation arises when considering full-depth water masses as end-members or mixtures: isotopic fractionation predominantly occurs in surface layers (e.g., evaporation and condensation), making the estimation of integrated fractionation factors across the entire water column highly uncertain. Consequently, this approach was deemed unsuitable for the present study.

d-excess, a key parameter, reflects kinetic fractionation processes during oceanic evaporation24. Evaporation increases δ¹⁸O while reducing d-excess, leading to an inverse correlation between d-excess and δ¹⁸O. This relationship, observed in the LZ (Luzon Strait), EH, WG (Western Guangdong Province), and PRE (Pearl River Estuary) voyages (Fig. 2e), signifies significant kinetic fractionation in these regions4,15,24. To account for these effects in the SIAR model, we identified samples from these four voyages where d-excess values fell below the minimum end-member d-excess or δ¹⁸O values exceeded the maximum end-member δ¹⁸O (gray points with black borders in Fig. 3a–d). These samples were interpreted as having undergone additional kinetic fractionation during transport from source regions to the study area.

Water isotope characteristics in the northern South China Sea. (a) Spatial distribution of surface δD. (b) Spatial distribution of bottom δD. (c) Spatial distribution of surface δ¹⁸O. (d) Spatial distribution of bottom δ¹⁸O. Black-bordered circles in (a–d) represent the GISS dataset; black double-headed arrows indicate adjacent stations used for comparison between this study and the GISS dataset. (e–f) Two-dimensional linear relationships between water isotope parameters and salinity.

Isotope corrections for the SIAR model. (a–d) Screening of scatter points for correction. (e–h) Deviation of scatter points relative to the δ¹⁸O–S linear regression. (i–l) Spatial distribution of corrected δD values in δD–S space. Gray points: non-end-member scatter points; gray points with black borders: pre-correction scatter points; green points with black borders: post-correction scatter points.

The δ¹⁸O–salinity (δ¹⁸O–S) relationship serves as an empirical diagnostic tool for distinguishing water masses and quantifying contributions from terrestrial runoff or glacial meltwater4,29. Both δ¹⁸O and salinity increase with evaporation, resulting in a positive linear correlation when mixing high-salinity/high-δ¹⁸O and low-salinity/low-δ¹⁸O water masses (Fig. 2f). Samples deviating above this regression line likely experienced enhanced evaporation. We thus attributed positive Δδ¹⁸O (δ¹⁸O deviations from the δ¹⁸O–S regression line) to additional kinetic fractionation. Following Benetti et al.5, Δδ¹⁸O values were corrected using the Δd-excess–Δδ¹⁸O relationship derived from the slope of the d-excess–δ¹⁸O regression line. Corrected samples are shown as green points with black borders in Fig. 3.

The primary uncertainty in this correction method stems from insensitivity to samples with low anomalous fractionation, which are assumed to reflect end-member mixing. However, since selected end-members and mixing zones are geographically proximate, they likely experienced similar meteorological and evaporative conditions, minimizing systematic biases in relative contribution estimates. Furthermore, kinetic fractionation associated with evaporation-condensation processes predominantly affects surface layers, whereas this study integrates full-depth water mass contributions. Consequently, surface-driven fractionation errors have limited impact on the quantification of subsurface contributions.

End-member selection and quantification of water mass transport

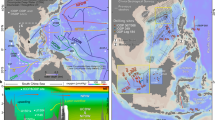

NSCS exhibits unique circulation features, necessitating careful identification of appropriate end-members and corresponding stations based on prior research before quantifying circulation characteristics (Fig. 4 and Table 2). In the northeastern SCS, Kuroshio water (KW) intrudes into the SCS all the year round via the Luzon Strait, with weaker intensity in summer and stronger in winter22,30. A southwestward slope current persists between 200 m and 1000 m depths, even during summer under prevailing southwesterly winds31,32. Along the southern coast near mainland China, a westward coastal current dominates west of the Pearl River Estuary for most of the summer, termed the Western Guangdong coastal current (WGCC)22. This current flows into the Beibu Gulf via the Qiongzhou Strait, with a branch diverging southward along the eastern coast of Hainan Island before entering the gulf8. The Beibu Gulf features a dual-gyre structure, with a cyclonic circulation in the north and an anticyclonic circulation in the south33. During summer, the coastal current along eastern Hainan Island flows northeastward under the influence of the southwestern monsoon34. This current, referred to as the SCS Warm Current (SCSWC), subsequently moves eastward along the shelf and eventually toward the western Luzon Strait22, designated as the coastal current (CC) end-member. Additionally, diluted water (DW) end-members from coastal river discharge and the South China Sea Water (SCSW) end-member representing southern SCS exchange were identified in specific coastal cruises.

Selection of end-member stations. (a) Major circulation patterns in the northern South China Sea during summer and spatial distribution of selected stations. (b) Temperature-salinity (T-S) diagram; gray points represent non-end-member scatter points. Abbreviations: CC (coastal current), KW (Krushio water), SCSW (South China Sea water), DW (diluted water), WGCC (Western Guangdong coastal current).

Data Records

The cruise information and references associated with the dataset are summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 1a. Sampling spanned depths of 0–3700 m in the northern South China Sea (SCS), with the number of sampling layers per station ranging from 1 to 12 (Fig. 1b,c). Spatial distributions of surface and bottom water isotopes are illustrated in Fig. 2a–d. All data are archived in the Excel file “water_isotope_NSCS.xlsx”. The file comprises two sheets:

-

Basic Data: Station, Longitude, Latitude, Date, Bot. (bottom depth in meters), Depth (sampling depth in meters), δD (in ‰), δ¹⁸O (in ‰), T (temperature in °C), S (practical salinity in psu), d_excess (in ‰), Voyage, δD correction (δD values corrected for SIAR modeling), and δ¹⁸O correction (δ¹⁸O values corrected for SIAR modeling). Missing values are denoted as NA.

-

Dynamic Data: Includes variables such as Area, Source (end-member name), Mean_δ¹⁸O (mean δ¹⁸O of the end-member), SD_δ¹⁸O (standard deviation of δ¹⁸O), Mean_δD, SD_δD, Contribution (%), End-Member Criteria, and Station Selection Features.

The SIAR model code is stored in the file “NSCS_SIAR.R.” For each subregion (Area), a dedicated folder ccontains three files: source-raw.xlsx (detailed station information for end-members), ConsumerData.xlsx (mixed water mass data), and SourceData.xlsx (end-member isotope data), which are used to execute the SIAR model. Spatial distributions of water mass contributions are presented in Fig. 5.

Technical Validation

To ensure internal consistency across measurement batches from six voyages, three replicate samples of aged open-ocean seawater were analyzed for each cruise. The results demonstrated that mean differences among triplicate samples were smaller than the analytical precision (±0.5‰ for δD and ±0.1‰ for δ¹⁸O) (Table 3), confirming appropriate sample preservation (no significant evaporative fractionation) and stable instrument calibration (no drift). However, potential offsets between datasets may arise from differences in internal standards, processing protocols, or instrument configurations. Thus, cross-validation with external datasets is critical for future data integration and expansion.

The NASA GISS Global Seawater Oxygen-18 Database, comprising over 26,000 δ¹⁸O values and limited δD values (relative to V-SMOW) since the 1950s14, includes only six stations in the SCS and adjacent western Pacific, all sampled in the 1990s (black-bordered points in Fig. 2a–d). Comparisons between the nearest stations in this study and the GISS dataset revealed minor discrepancies in bottom δ¹⁸O (mean difference: 0.01‰, within the δ¹⁸O range of [−2, 1]‰) and bottom δD (0.31‰ and 2.30‰, within the δD range of [−15, 20]‰). Surface δD differences were 2.18‰ and 1.06‰, while surface δ¹⁸O exhibited a larger mean discrepancy (0.92‰), likely due to Kuroshio influence and associated dynamic processes. Overall, isotopic values in this dataset showed a slight positive bias relative to GISS, suggesting systematic offsets.

Finally, water mass contributions in the NSCS, as quantified by SIAR, align with qualitative circulation features (Figs. 4, 5). For example, the SIAR-derived 75% contribution of the SCSW end-member in the southern EH area corroborates prior observations of strong northward currents along eastern Hainan Island under summer southwestern monsoons34. Similarly, Kuroshio intrusion and Pearl River discharge were identified as significant factors influencing volume transport in the northern PRE region35, with our quantified contributions also revealing 36% Kuroshio water (KW) and 35% diluted water (DW) in this area. Furthermore, the 35% DW contribution in PRE substantially exceeds the 17% DW in EH, attributable to the Pearl River (China’s second-largest river) whose summer-dominant discharge exerts extensive influence across the NSCS36. Notably, the DW end-member contribution reaches 46% in the NBBG, primarily due to multiple rivers along its coast and restricted water exchange capacity characteristic of this semi-enclosed bay17. These results validate the robustness of the SIAR model in resolving regional circulation dynamics.

Code availability

All data and code used for graphing are permanently available on the FAIR compliant repository Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1557767637.

References

Craig, H., & Gordon, L. I. Deuterium and oxygen 18 variations in the ocean and the marine atmosphere, Stable Isotopes in Oceanographic Studies and Paleotemperatures E. In Proceedings of the Third Spoleto Conference, Spoleto, Italy, edited by Tongiori, E. (pp. 9–130) (1965).

Lian, E. et al. Kuroshio subsurface water feeds the wintertime Taiwan Warm Current on the inner East China Sea shelf. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 121, 4790–4803 (2016).

Dubinina, E. O., Kossova, S. A., Miroshnikov, A. Y. & Fyaizullina, R. V. Isotope parameters (δD, δ 18 O) and sources of freshwater input to Kara Sea. Oceanology 57, 31–40 (2017).

Deshpande, R. D. et al. Spatio-temporal distributions of δ¹⁸O, δD and salinity in the Arabian Sea: identifying processes and controls. Marine Chemistry 157, 144–161 (2013).

Benetti, M. et al. Composition of freshwater in the spring of 2014 on the southern L abrador shelf and slope. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 122, 1102–1121 (2017).

Wang, B., Zhang, H., Liang, X., Li, X. & Wang, F. Cumulative effects of cascade dams on river water cycle: Evidence from hydrogen and oxygen isotopes. Journal of Hydrology 568, 604–610 (2019).

Chen, D. et al. Origin of the springtime South China Sea Warm Current in the southwestern Taiwan Strait: Evidence from seawater oxygen isotope. Science China Earth Sciences 63, 1564–1576 (2020).

Liu, S. et al. Seasonal distribution of water masses and their impacts on nutrient supply in the southern Beibu Gulf. Marine Environmental Research 194, 106311 (2024).

Sengupta, S., Parekh, A., Chakraborty, S., Ravi Kumar, K. & Bose, T. Vertical variation of oxygen isotope in Bay of Bengal and its relationships with water masses. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 118, 6411–6424 (2013).

Wu, J. et al. Water mass processes between the South China Sea and the Western Pacific through the Luzon Strait: Insights from hydrogen and oxygen isotopes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 126, e2021JC017484 (2021).

Zhou, F. et al. Using stable isotopes (δ¹⁸O and δD) to study the dynamics of upwelling and other oceanic processes in northwestern South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 127, e2021JC017972 (2022).

Xu, X., Werner, M., Butzin, M. & Lohmann, G. Water isotope variations in the global ocean model MPI-OM. Geoscientific Model Development 5, 809–818 (2012).

Amrhein, D. E., Gebbie, G., Marchal, O. & Wunsch, C. Inferring surface water equilibrium calcite δ¹⁸O during the last deglacial period from benthic foraminiferal records: Implications for ocean circulation. Paleoceanography 30, 1470–1489 (2015).

Schmidt, G.A., Bigg, G. R. & Rohling, E. J. Global Seawater Oxygen-18 Database - v1.22 https://data.giss.nasa.gov/o18data/ (1999).

Reverdin, G. et al. The CISE-LOCEAN seawater isotopic database (1998–2021). Earth System Science Data 14, 2721–2735 (2022).

Lao, Q. et al. Increasing intrusion of high salinity water alters the mariculture activities in Zhanjiang Bay during the past two decades identified by dual water isotopes. Journal of Environmental Management 320, 115815 (2022).

Lao, Q. et al. Quantification of the seasonal intrusion of water masses and their impact on nutrients in the Beibu Gulf using dual water isotopes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 127, e2021JC018065 (2022).

Wang, D. et al. An analysis of the current deflection around Dongsha Islands in the northern South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 118, 490–501 (2013).

Bigg, G. R. & Rohling, E. J. An oxygen isotope data set for marine waters. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 105, 8527–8535 (2000).

Rahman, A., Khan, M. A., Singh, A. & Kumar, S. Hydrological characteristics of the Bay of Bengal water column using δ¹⁸O during the Indian summer monsoon. Continental Shelf Research 226, 104491 (2021).

Wang, Q. et al. Dynamic of the upper cross-isobath’s flow on the northern South China Sea in summer. Aquatic Ecosystem Health & Management 18, 357–366 (2015).

Shu, Y., Wang, Q. & Zu, T. Progress on shelf and slope circulation in the northern South China Sea. Science China Earth Sciences 61, 560–571 (2018).

Wang, D., Hong, B., Gan, J. & Xu, H. Numerical investigation on propulsion of the counter-wind current in the northern South China Sea in winter. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 57, 1206–1221 (2010).

Dansgaard, W. Stable isotopes in precipitation. Tellus 16, 436–468 (1964).

Jackson, A. L., Inger, R., Bearhop, S. & Parnell, A. Erroneous behaviour of MixSIR, a recently published Bayesian isotope mixing model: a discussion of Moore & Semmens (2008). Ecology letters 12, E1–E5 (2009).

Moore, J. W. & Semmens, B. X. Incorporating uncertainty and prior information into stable isotope mixing models. Ecology letters 11, 470–480 (2008).

Zhang, M., Zhi, Y., Shi, J. & Wu, L. Apportionment and uncertainty analysis of nitrate sources based on the dual isotope approach and a Bayesian isotope mixing model at the watershed scale. Science of the Total Environment 639, 1175–1187 (2018).

Jian, X. et al. Using dual water isotopes to quantify the mixing of water masses in the Pearl River Estuary and the adjacent northern South China Sea. Frontiers in Marine Science 9, 987685 (2022).

Singh, A., Mohiuddin, A., Ramesh, R. & Raghav, S. Estimating the loss of Himalayan Glaciers under global warming using the δ¹⁸O–salinity relation in the Bay of Bengal. Environmental Science & Technology Letters 1, 249–253 (2014).

Liu, S. et al. Potential carbon sources and sinks in frontal zones dominated respectively by mesoscale and submesoscale processes in the Luzon Strait. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 217, 104461 (2025).

Jilan, S. Overview of the South China Sea circulation and its influence on the coastal physical oceanography outside the Pearl River Estuary. Continental Shelf Research 24, 1745–1760 (2004).

Yuan, Y., Liao, G. & Yang, C. The Kuroshio near the Luzon Strait and circulation in the northern South China Sea during August and September 1994. Journal of oceanography 64, 777–788 (2008).

Gao, J., Wu, G. & Ya, H. Review of the circulation in the beibu gulf, South China Sea. Continental Shelf Research 138, 106–119 (2017).

Liu, S. et al. Impacts of marine heatwave events on three distinct upwelling systems and their implications for marine ecosystems in the Northwestern South China Sea. Remote Sensing 16, 131 (2023).

Liu, J., Dai, J., Xu, D., Wang, J. & Yuan, Y. Seasonal and interannual variability in coastal circulations in the Northern South China Sea. Water 10(4), 520 (2018).

Xu, J. et al. Phosphorus limitation in the northern South China Sea during late summer: influence of the Pearl River. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 55, 1330–1342 (2008).

Liu, S. SihaiLiu/NSCS_dual_water_isotope: A Hydrogen and Oxygen Isotope Dataset for Quantifying Summer Water Mass Transport in the Northern South China Sea (v1.0.0). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15577676 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Fei Yu and Xiaohua Zhu for their support in collecting LZ water samples. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42276047, U1901213), Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (2023B1515120029).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. curated the database and wrote the first draft of the paper. F.C. directed the project. All authors contributed to the data collection. All authors corrected and oversaw the production of the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S., Chen, C., Lu, X. et al. A dual water isotope dataset for quantifying summer water mass transport in the northern South China Sea. Sci Data 12, 1123 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05444-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05444-4