Abstract

Hurricane Ian caused aboveground biomass density (AGBD) losses across Florida’s forests in the United States, highlighting the need for accurate, large-scale monitoring tools. We combined Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI) LiDAR data with synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and passive optical satellite imagery to model GEDI AGBD as a function of image-derived data, enabling predictions across the study area and producing continuous AGBD maps. Validation using in situ field data demonstrated high model performance, with an R2 of 0.93 and a root mean square difference (RMSD) of 39.3%. Spatial uncertainty reflecting bootstrap-derived variance remained consistent, with relative standard errors around 90% across the years analyzed. The data are accessible through a web application, RapidFEM4D, enabling researchers and stakeholders to assess AGBD maps for areas of interest. These datasets support monitoring forest recovery, assessing carbon dynamics, and guiding post-hurricane management and restoration. The RapidFEM4D platform facilitates access and analysis of Hurricane Ian’s impact on Florida’s forests, empowering stakeholders with actionable insights and offering a model for similar efforts in other hurricane-prone regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Hurricane Ian, the major hurricane of the 2022 North Atlantic hurricane season, caused widespread devastation across parts of the Caribbean and the southeastern United States. Originating off the west coast of Africa and intensifying as it crossed the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico, Ian made landfall in Florida on September 28, 2022, as a powerful Category 4 hurricane with sustained winds reaching 240 km h−1. Its destructive path extended from Cuba to the southeastern United States, including Florida, South Carolina, and North Carolina, leaving behind catastrophic flooding, wind damage, and storm surges. With an estimated cost of $111.8 billion, Hurricane Ian became the third costliest tropical cyclone in U.S. history1.

Beyond the significant economic and human losses, the ecological impact of hurricanes is profound, particularly on aboveground biomass density (AGBD) in forest ecosystems2,3,4. Hurricanes can cause severe tree mortality, canopy loss, and structural damage5, along with shifts in species composition6 and other abiotic changes7. In addition, post-storm interventions such as salvage logging can further boost these impacts8, impacting forest recovery and altering AGBD and carbon dynamics9,10. Monitoring these impacts is critical for understanding ecosystem resilience and informing management strategies, requiring accurate measurements of AGBD losses and structural changes.

Previous hurricane damage assessments often relied on field plots, aerial photography, or optical remote sensing, which provided limited structural information and were restricted by cloud cover or inconsistent spatial resolution11,12,13. This shift toward structure-based assessment supported the widespread adoption of LiDAR, which has become essential for quantifying hurricane-induced biomass changes14,15. The Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI) mission represents a major leap forward in measuring forest biomass and carbon stocks from space, using LiDAR to capture high-resolution vertical profiles of forest canopies16. The waveform data from GEDI footprints are transformed into estimates of AGBD through the L4A product calibration models. This product provides globally distributed, footprint-level AGBD estimates, derived using machine learning models trained on field inventory and airborne LiDAR reference datasets17. However, GEDI’s sampling strategy, which collects data along narrow transects, limits its ability to produce continuous, wall-to-wall maps. To overcome this limitation, GEDI data must be integrated with other remote sensing sources, such as optical or radar imagery from satellites18,19,20.

Data integration approaches that combine GEDI with multisource remote sensing, such as Sentinel-121, Sentinel-222, Landsat23, and ALOS-224, have proven effective for producing spatially continuous and accurate estimates of AGBD. They can leverage the complementary strengths of each sensor, where GEDI provides vertical structure information, while optical and radar data offer spatial coverage and sensitivity to vegetation condition and canopy structure. This integration improves estimation accuracy across diverse forest types and disturbance gradients25, and enables consistent post-hurricane assessments by reducing reliance on GEDI footprints alone26.

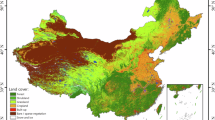

To address the biomass losses caused by Hurricane Ian, we generated detailed AGBD maps using a combination of GEDI data with synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and passive optical imagery, allowing us to produce continuous, wall-to-wall coverage of impacted areas. The study area was defined as the forested area within a 200 km buffer surrounding the path of Hurricane Ian (Fig. 1). These maps are provided through RapidFEM4D (Rapid Forest Ecosystem Monitoring in Four Dimensions), an open-access dataset designed to represent the hurricane’s effects on forest biomass. The dataset is publicly available for use by researchers, land managers, and policymakers, providing spatially explicit information to support analysis of forest recovery, carbon dynamics, and post-hurricane conditions.

Methods

Field data collection and reference AGBD prediction

Forest inventory data were collected in situ in spring 2023 and 2024. A total of 27 plots, each measuring 25 × 25 meters, were strategically sampled across four study areas to represent a full gradient of tree density, basal area, and AGBD, ranging from dense woodlands to sparsely treed shrublands (Table 1). The sampling design aimed to improve model training and validation to enhance model robustness and predictive reliability. Two study sites in Florida, United States, were visited in spring-summer 2023, Myakka State Forest and Okaloacoochee Slough State Forest, and have experienced severe AGBD loss due to Hurricane Ian (Table 1). Myakka State Forest spans a landscape characterized by dry prairie, pine flatwoods, and wetland ecosystems, making it representative of hurricane-prone coastal forests. Okaloacoochee Slough State Forest, on the other hand, contains a diverse mix of cypress swamps, pine flatwoods, and hardwood hammocks. Two other study areas, the University of Florida’s Austin Cary Forest and the Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences (FAS) Millhopper Unit, are located near Gainesville in north-central Florida, United States, and were visited in summer-fall 2024 (Table 1). These areas consist primarily of managed stands of loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.), longleaf pine (Pinus palustris Mill.), and slash pine (Pinus elliottii Engelm. var. elliottii). Both areas experienced minimal to no damage from Hurricane Ian, providing a reference for undisturbed forest conditions.

Sampling plots were selected based on visual assessment of representative hurricane damage, accessibility, and avoiding interference from roads or other land cover types. For example, when setting a plot center, we accounted for the distance to the nearest border plus a safe margin of approximately 30 meters, ensuring that the plot remained within a homogeneous forested area. This safe margin corresponds to the spatial resolution of remote sensing data, minimizing the risk of mixed pixels that could introduce information from non-forest features. At each sampling plot, the plot center was marked and plot boundaries were established using distance tapes to define the corners and edges accurately. Within each plot, only standing and live trees with diameter at breast height (DBH) greater than 10 cm were identified and measured. Tree height was recorded using a rangefinder; however, in plots with a high density of trees or limited visibility of tree tops, height measurements were reduced to approximately 20% of the individuals to improve efficiency while maintaining representative sampling. The distribution of tree density, basal area, and AGBD across all plots, along with representative photos from low, medium, and high-AGBD sites, is shown in Fig. 2.

Distribution of tree density (trees ha−1), basal area (m² ha−1), and aboveground biomass density (AGBD, Mg ha−1) across the 27 inventory plots. Boxplots summarize variability, and representative photos illustrate plots with different forest conditions sampled in the study. Informed consent was obtained from the individual shown in the photo.

Field data was organized and the reference AGBD from sample plots was calculated through a two-step modeling approach. First, missing tree height values were estimated using species-specific height-DBH relationships derived from the collected data, ensuring consistency in height estimation across all measured trees. These height models allowed for a more complete dataset, reducing bias in subsequent biomass calculations. Second, aboveground biomass (AGB) was estimated for each tree as a function of species, DBH, and height using species-specific allometric equations (Table 2). The sum of individual tree predictions within each plot provided the total AGB in kilograms per plot. This value was first converted to megagrams to standardize units before being scaled to a per-hectare basis (Mg ha−1), resulting in AGBD.

Remotely sensed data acquisition

We integrated data from GEDI, Harmonized Landsat Sentinel (HLS), Sentinel-1C, and ancillary datasets to capture AGBD from multiple perspectives, leveraging different sensors and measurement approaches to enhance data reliability and completeness. GEDI provided biomass estimates from lidar-derived vegetation structure, collected along 25-meter footprints spaced 60 meters apart along-track. The instrument uses three lasers split into eight beams: four strong (full power) and four weak (coverage), resulting in eight parallel ground tracks spaced 600 meters apart27 (Fig. 3b). It operates between 51.6°N and 51.6°S, providing near-global sampling across vegetated areas. The GEDI Level 4 A data product provides near-global AGBD estimates derived from three-dimensional vegetation structure28. For this study, we analyzed data collected in April across 2019–2022 (Fig. 3a), a period selected based on pre-modeling tests identifying April as optimal for consistent vegetation measurements. Temporal filtering allowed us to account for inter-annual variability in biomass and ensured model robustness against environmental changes. Although GEDI ceased data collection in 2023, we used the multi-year GEDI dataset to train a temporally generalized model, which can be further applied to other years. In addition, we applied a series of filters to refine the data quality of each dataset (Table 3).

We integrated data from HLS, Sentinel-1C, and ancillary data using Google Earth Engine (GEE29), to enhance the upscaling of GEDI L4A data. A temporal window from March 1 to May 31 for 2019–2022 was selected to align with the GEDI dataset while increasing the likelihood of cloud-free HLS observations. A per-pixel median was calculated within the period, minimizing noise and approximating the central GEDI acquisition period. This median composite was then used to derive all subsequent covariates. Time-series analysis confirmed minimal inter-annual variability, ensuring that the selected window reliably represented consistent vegetation characteristics, including greenness, canopy structure, and biomass. In addition, the layers were standardized to a 30-m resolution for spatial consistency using a nearest neighbor interpolation from GEE.

HLS imagery provided surface reflectance data in blue, green, red, NIR, SWIR1, and SWIR2 bands, combining observations from Landsat 8/9 OLI and Sentinel-2A/B MSI for global 30-m resolution coverage every 2–3 days. Cloud and shadow masking was performed using the Fmask algorithm30. Using the HLSL30 catalog on GEE, we selected images with less than 30% cloud cover for the study area. For acquiring and processing Sentinel-1C data, we utilized the interferometric wide (IW) mode for its capability to deliver high-resolution imagery suitable for detailed vegetation and land cover analysis. Data from vertical transmit–vertical receive (VV) and vertical transmit–horizontal receive (VH) polarizations were selected, as VV primarily captures surface scattering, while VH is sensitive to volume scattering from vegetation structure. Using both polarizations provides complementary information for characterizing forest and its respective AGBD properties31. Ancillary data from NASADEM provided elevation, slope, and aspect to assess topography’s impact on vegetation and biomass. Latitude and longitude were also included as predictors to enable spatial analysis of ecological dynamics across forest patches. Additional preprocessing applied to optical datasets included aligning pixels across sources, standardizing spatial resolution, and converting reflectance values to integer format to improve processing efficiency.

Image covariates and stacking

We generated an image stack of 260 covariates from HLS, Sentinel-1C, and ancillary datasets for AGBD modeling. Spatial transformations, including 3 × 3 kernel window analyses and Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) texture metrics, captured fine-scale landscape structure and texture. Kernel analyses calculated mean, standard deviation, maximum, and minimum values for HLS, Sentinel-1C, and DEM variables, quantifying local variability. GLCM, applied to HLS bands using a 3-pixel window, is a second-order statistical method that quantifies image texture by measuring how often pairs of pixel values occur in a specified spatial relationship. It describes texture by capturing spatial patterns such as contrast, homogeneity, entropy, and correlation, using 8-bit grayscale inputs to generate 18 standard texture indices32. These covariates were consolidated into a dataset for further analysis (Supplementary Table 1).

AGBD modeling and upscaling

AGBD was modeled using image-derived data (Fig. 4a). From the image stack, 1,000 GEDI L4A footprints were sampled across all available years, ensuring spatial independence by applying a 1.3 km semivariogram-derived distance threshold33. The dataset was split into 70% training and 30% validation subsets to optimize learning and evaluation.

Flowchart of the proposed method for AGBD prediction. Panel (a) illustrates the steps for acquiring and processing GEDI AGBD data (light blue boxes) and other remote sensing predictors of AGBD (light orange boxes), resulting in 260 covariates. Panel (b) describes the modeling and upscaling framework used in the study. Panel (c) explains the map accuracy, uncertainty assessment process, and technical validation.

A Random Forest (RF) regressor34 implemented in the Scikit-learn package35 was used to estimate AGBD, configured with 250 trees for a balance of accuracy and efficiency. Feature selection employed Scikit-learn’s SelectFromModel, retaining features with importance scores above the mean to enhance model performance. A bootstrap procedure with 100 iterations was applied to ensure robust and reliable outcomes. For each iteration, a random sample with replacement was used to train the RF model and generate an AGBD map. The trained model was then applied to the image stack, producing a spatially explicit AGBD map for the study area (Fig. 4b). We calculated model performance metrics based on predicted and observed AGBD values. The equations below define the Mean Difference (MD; Eq. 1), Root Mean Square Difference (RMSD; Eq. 3), their relative forms (%MD and %RMSD; Eqs. 2 and 4), and the coefficient of determination R2 (Eq. 5).

Where, \({y}_{i}\) is the reference AGBD in the GEDI footprint i, \({\hat{y}}_{i}\) is our estimated AGBD in the GEDI footprint i, and \(\bar{y}\) is the mean of the reference AGBD sample used for testing. %RMSD (Eq. 4) and %MD (Eq. 2) were calculated by dividing the respective absolute values (Eqs. 1 and 3) by the mean of GEDI AGBD observations used for model testing.

Damage assessment through AGBD

Hurricane damage classification was derived from the estimated AGBD loss, calculated as the difference between the pre- and post-hurricane AGBD maps. To assess the relative impact, we computed the percentage of biomass loss based on pre-hurricane conditions. The resulting values of loss were then categorized into five hurricane severity classes: 0–5% (no damage), 5–20% (light damage), 20–35% (moderate damage), 35–50% (severe damage), and >50% (catastrophic damage). Classification was included to support interpretation and decision-making by stakeholders. We focused solely on biomass loss; potential AGBD gains, such as regrowth or recovery, were not evaluated, as our objective was to generate detailed AGBD maps specifically to assess the biomass losses caused by Hurricane Ian.

We overlaid the damage classification map with Florida counties to assess the spatial distribution of hurricane impacts at the administrative level (Fig. 8). The total area of each damage class was quantified within each county, followed by the calculation of its relative percentage of the total damaged area. This analysis provided a visualization of the hurricane’s impact, highlighting regional differences in hurricane severity. For example, the maps reveal counties with a higher percentage of catastrophic damage, indicating areas where forests experienced the most extensive biomass loss.

RapidFEM4D

The final prediction maps and associated uncertainties, specifically generated to assess the impacts of Hurricane Ian, were uploaded to RapidFEM4D, a cost-free, single-page web application designed to enable researchers to assess AGBD maps for affected areas. This dynamic platform provides an intuitive interface for visualizing, interacting with, and analyzing AGBD maps, making it accessible to users with varying levels of remote sensing expertise (Fig. 5). The platform’s features include a location search tool for quickly navigating to specific areas and an opacity slider for adjusting layer transparency

An additional feature of the platform allows users to draw custom polygons or upload shapefiles of areas of interest, enabling the extraction of average values from the active layer within the selected region. This function enables users to compute AGBD estimates, uncertainty levels, and biomass loss for specific locations, facilitating localized analyses of hurricane impacts. In addition to AGBD data, the platform integrates Hurricane Ian’s track and demographic information about Florida, including the hurricane’s impact on counties.

Data Records

The dataset is available on the USDA ARS National Agricultural Library Ag Data Commons36. It consists of six raster files at a spatial resolution of 30 meters in GeoTIFF format, each approximately 400 MB in size with a Uint16 data type. AGBD values were scaled by 100 for storage as integers; users should divide by 100 to retrieve biomass estimates in Mg ha−1. All GeoTIFF files use the EPSG:4326 coordinate reference system.

-

2022 RapidFEM4D AGBD prediction

-

2023 RapidFEM4D AGBD prediction

-

2024 RapidFEM4D AGBD prediction

-

2022 RapidFEM4D AGBD uncertainty

-

2023 RapidFEM4D AGBD uncertainty

-

2024 RapidFEM4D AGBD uncertainty

In addition, the field data is available in CSV format (RapidFEM4D field data.csv), containing tree-level measurements collected during the study. The dataset includes the following columns: DATE_OF_ACQUISITION, SITE, PLOT_X, PLOT_Y, PLOT_ID, TREE_ID, SPECIES, DBH_CM, and HEIGHT_M. These attributes document the location, species, and structural characteristics of individual trees measured across all sampled plots.

The dataset is available for visualization at http://rapidfem4d.silvalab-uf.com/. It includes AGBD predictions followed by a change detection map and damage classification for the 2022–2023 period to capture the pre- and post-Hurricane Ian conditions (Fig. 6) and the respective uncertainty maps for the years 2022, 2023, and 2024 (Fig. 7).

Technical validation

Internal validation of model performance

Internal validation of model performance was evaluated through both absolute and relative MD, RMSD, and R2 (Fig. 4c). It demonstrated reasonable predictive accuracy, capturing biomass variability across the study area. Performance metrics remained within acceptable ranges, indicating reliable AGBD estimates. The MD ranged from −4.8 to 9.2 Mg ha−1, with percent varying between −5.8% and 12.7%, reflecting low bias (Fig. 9a). The near-zero median MD suggests that, on average, the model does not overestimate or underestimate AGBD, which enhances reliability for biomass assessments and post-hurricane forest monitoring in the study area. The error-related metrics provided further insight into the model internal validation and the magnitude of deviations from observed AGBD values. The RMSD had a median value of 48.3 Mg ha−1, while the percent reached a median of 61.5% (Fig. 9b). The R2 ranged from 0.42 to 0.64, indicating a moderate correlation between predicted and observed AGBD values (Fig. 9c).

Internal validation boxplots of model performance based on 100 bootstrapped iterations. (a) Absolute error metrics include mean difference (MD) and root mean square difference (RMSD). (b) Relative error metrics include percent mean difference (%MD) and percent root mean square difference (%RMSD). (c) Coefficient of determination (R2).

External validation of map accuracies

External validation was divided into two parts: in situ validation and spatial uncertainty assessment of AGBD estimates. In situ validation involved direct comparisons between predicted AGBD values from the maps and field-measured AGBD from the 27 plots. A 1:1 plot illustrated the agreement between predicted and observed AGBD values, providing a graphical representation of model performance, and statistical metrics were calculated to quantify accuracy and precision, including MD, %MD, RMSD, %RMSD, and R2 (Fig. 10). Deviations from the 1:1 line indicate over- or underestimation trends, while the spread of points reflects the variability and precision of the predictions. Our results demonstrated a high correlation, with an R2 of 0.93, indicating strong agreement between predicted and observed in situ AGBD values. The model exhibited a slight negative bias, as reflected in the MD of −10.5 Mg ha−1 and %MD of −9.5%, suggesting a small systematic underestimation of biomass. The overall prediction error was quantified by an RMSD of 43.3 Mg ha−1, with a relative RMSD of 39.3%, capturing the variability in biomass estimates across the study area. These results demonstrate the model’s reliability in predicting AGBD, with minimal bias and strong predictive accuracy, reinforcing its applicability for post-hurricane biomass assessments.

Comparison of in situ estimates and derived wall-to-wall AGBD estimates. The black dashed line represents the 1:1 relationship, the solid black line is the best-fit linear model for the pairwise measurements, and vertical lines indicate the standard deviation from each estimate. Statistical metrics are computed by the linear relationship between predicted AGBD and the 27 field plots (observed AGBD). Field pictures illustrate real AGBD conditions of selected plots, highlighting (a) an underestimated, (b) a well-fitted, and (c) an overestimated example.

The spatial uncertainty in AGBD predictions for each year was quantified using the estimated mean \(E(\mu )\) AGBD, calculated as the average of predicted values, representing the central tendency of the predictions (Eq. 6). The 95% confidence interval provides the range within which the true mean is expected to fall. Spatial variability was assessed through the total variance \(V[\hat{E(\mu )}]\) derived from pixel-level bootstrap estimates (Eq. 7). From this variance, the standard error \(\left(\overline{{SE}}\right)\) quantifies the average deviation of the estimated means from the true population mean (Eq. 8). The relative standard error \(\left( \% \overline{{SE}}\right)\) is calculated as \(\overline{{SE}}\) divided by the mean AGBD, offering a percentage-based representation of estimation uncertainty (Eq. 9).

The central tendency of AGBD for the entire study area ranged from 50 to 60 Mg ha−1 over the years analyzed. The increase in the estimated mean AGBD to 58.2 Mg ha−1 in 2024 suggests a gradual recovery of forest biomass following the significant losses caused by Hurricane Ian. The %SE for the entire area consistently remained around 90%, reflecting high spatial uncertainty (Table 4). However, it is important to note that this value encompasses the entire study area, including regions with inherently higher uncertainty. These high uncertainties can be attributed to several factors, including cloud cover that affects data acquisition, land cover dynamics such as flooding in coastal zones, and sensor limitations like saturation in densely vegetated areas. Additionally, model limitations, particularly in capturing complex canopy structures or sparsely vegetated regions, contribute to elevated uncertainty levels.

Usage Notes

The RapidFEM4D AGBD maps serve as a reference estimation for the scientific and public communities working on post-hurricane forest recovery and carbon assessment in a knowledge co-production manner. They are expected to be particularly useful for the calibration, validation, and direct comparison of remote sensing-based biomass estimation models, enhancing the accuracy of broader-scale monitoring efforts, and pinpointing where efforts are needed for recovery and restoration. The temporal continuity of these maps is also an important feature once it enables the tracking of biomass dynamics and provides insights into disturbance impacts, recovery trajectories, and carbon fluxes over time. While developed in Florida, the data and methodology (Bueno et al., in review) can be transferable for use in other hurricane-prone regions, as well as areas affected by large-scale disturbances (e.g., fire, landslide, bark beetle infestation).

Uncertainty maps provide essential context for interpreting AGBD estimates, highlighting areas where predictions may be less reliable due to model limitations. Higher uncertainty typically occurs in regions with greater biomass. The 30-m resolution of these maps imposes certain constraints, as fine-scale variations in biomass distribution may be smoothed or underrepresented. Small forest gaps, individual trees, and fine-scale structural differences might not be fully captured, leading to potential discrepancies when comparing with higher-resolution datasets. Users conducting independent accuracy assessments or validation should compare AGBD estimates against high-resolution field or airborne LiDAR data, ensuring spatial alignment and considering scale differences. Employing bootstrapped sampling methods and statistical confidence intervals can further refine uncertainty evaluations.

It is important to note that this dataset does not differentiate between native and planted forests during the modeling and upscaling. Users interpreting damage or biomass changes in areas with known harvesting, thinning, or forest management may consider applying external forest type or management masks to isolate these effects.

Code availability

All steps for GEDI, HLS, and Sentinel-1C data acquisition, preprocessing, covariate generation, stacking, as well as AGBD modeling and upscaling were performed using Python and the GEE environment. The scripts used for these processes are available on GitHub (https://github.com/inaciotbueno/rapidfem4d). Field data used for map validation is available on the USDA ARS National Agricultural Library Ag Data Commons36.

References

Bucci, L., Alaka, L., Hagen, A., Delgado, S. & Beven, J. National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Report. https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL092022_Ian.pdf (2023).

Bellanthudawa, B. K. A. & Chang, N. Bin. Hurricane Irma impact on biophysical and biochemical features of canopy vegetation in the Santa Fe River Basin, Florida. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 102, 102427 (2021).

D’Amato, A. W. et al. Long‐term structural and biomass dynamics of virgin Tsuga canadensis–Pinus strobus forests after hurricane disturbance. Ecology 98, 721–733 (2017).

Seidl, R., Spies, T. A., Peterson, D. L., Stephens, S. L. & Hicke, J. A. Searching for resilience: addressing the impacts of changing disturbance regimes on forest ecosystem services. J. Appl. Ecol. 53, 120–129 (2016).

Whelan, A. W., Bigelow, S. W., Staudhammer, C. L., Starr, G. & Cannon, J. B. Damage prediction for planted longleaf pine in extreme winds. For. Ecol. Manage. 560, 121828 (2024).

Zhang, J., Heartsill-Scalley, T. & Bras, R. L. Parsing Long-Term Tree Recruitment, Growth, and Mortality to Identify Hurricane Effects on Structural and Compositional Change in a Tropical Forest. Forests 13, 796 (2022).

Van Beusekom, A. E., González, G., Stankavich, S., Zimmerman, J. K. & Ramírez, A. Understanding tropical forest abiotic response to hurricanes using experimental manipulations, field observations, and satellite data. Biogeosciences 17, 3149–3163 (2020).

Taeroe, A. et al. Recovery of temperate and boreal forests after windthrow and the impacts of salvage logging. A quantitative review. For. Ecol. Manage. 446, 304–316 (2019).

Chambers, J. Q. et al. Hurricane Katrina’s Carbon Footprint on U.S. Gulf Coast Forests. Science (80-.). 318, 1107–1107 (2007).

Lodge, D., Winter, D., González, G. & Clum, N. Effects of Hurricane-Felled Tree Trunks on Soil Carbon, Nitrogen, Microbial Biomass, and Root Length in a Wet Tropical Forest. Forests 7, 264 (2016).

Parker, G., Martínez-Yrízar, A., Álvarez-Yépiz, J. C., Maass, M. & Araiza, S. Effects of hurricane disturbance on a tropical dry forest canopy in western Mexico. For. Ecol. Manage. 426, 39–52 (2018).

Wang, W., Qu, J. J., Hao, X., Liu, Y. & Stanturf, J. A. Post-hurricane forest damage assessment using satellite remote sensing. Agric. For. Meteorol. 150, 122–132 (2010).

Bloom, D. E., Bomfim, B., Feng, Y. & Kueppers, L. M. Combining field and remote sensing data to estimate forest canopy damage and recovery following tropical cyclones across tropical regions. Environ. Res. Ecol. 2, 035004 (2023).

Chavez, S. et al. Estimating Structural Damage to Mangrove Forests Using Airborne Lidar Imagery: Case Study of Damage Induced by the 2017 Hurricane Irma to Mangroves in the Florida Everglades. USA. Sensors 23, 6669 (2023).

Dolan, K. A. et al. Using ICESat’s Geoscience Laser Altimeter System (GLAS) to assess large-scale forest disturbance caused by hurricane Katrina. Remote Sens. Environ. 115, 86–96 (2011).

Dubayah, R. et al. The Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation: High-resolution laser ranging of the Earth’s forests and topography. Sci. Remote Sens. 1, 100002 (2020).

Liang, M., Duncanson, L., Silva, J. A. & Sedano, F. Quantifying aboveground biomass dynamics from charcoal degradation in Mozambique using GEDI Lidar and Landsat. Remote Sens. Environ. 284, 113367 (2023).

Tamiminia, H., Salehi, B., Mahdianpari, M. & Goulden, T. State-wide forest canopy height and aboveground biomass map for New York with 10 m resolution, integrating GEDI, Sentinel-1, and Sentinel-2 data. Ecol. Inform. 79, 102404 (2024).

Wang, D. et al. Estimating aboveground biomass of the mangrove forests on northeast Hainan Island in China using an upscaling method from field plots, UAV-LiDAR data and Sentinel-2 imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 85, 101986 (2020).

Shendryk, Y. Fusing GEDI with earth observation data for large area aboveground biomass mapping. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 115, 103108 (2022).

Mohite, J. et al. Forest aboveground biomass estimation by GEDI and multi-source EO data fusion over Indian forest. Int. J. Remote Sens. 45, 1304–1338 (2024).

Guo, Q. et al. Combining GEDI and sentinel data to estimate forest canopy mean height and aboveground biomass. Ecol. Inform. 78, 102348 (2023).

Francini, S., D’Amico, G., Vangi, E., Borghi, C. & Chirici, G. Integrating GEDI and Landsat: Spaceborne Lidar and Four Decades of Optical Imagery for the Analysis of Forest Disturbances and Biomass Changes in Italy. Sensors 22, 2015 (2022).

Padalia, H., Prakash, A. & Watham, T. Modelling aboveground biomass of a multistage managed forest through synergistic use of Landsat-OLI, ALOS-2 L-band SAR and GEDI metrics. Ecol. Inform. 77, 102234 (2023).

Silva, C. A. et al. Fusing simulated GEDI, ICESat-2 and NISAR data for regional aboveground biomass mapping. Remote Sens. Environ. 253, 112234 (2021).

Holcomb, A., Burns, P., Keshav, S. & Coomes, D. A. Repeat GEDI footprints measure the effects of tropical forest disturbances. Remote Sens. Environ. 308, 114174 (2024).

Dubayah, R. et al. GEDI launches a new era of biomass inference from space. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 095001 (2022).

Duncanson, L. et al. Aboveground biomass density models for NASA’s Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI) lidar mission. Remote Sens. Environ. 270, 112845 (2022).

Gorelick, N. et al. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 202, 18–27 (2017).

Claverie, M. et al. The Harmonized Landsat and Sentinel-2 surface reflectance data set. Remote Sens. Environ. 219, 145–161 (2018).

Robinson, C., Saatchi, S., Neumann, M. & Gillespie, T. Impacts of Spatial Variability on Aboveground Biomass Estimation from L-Band Radar in a Temperate Forest. Remote Sens. 5, 1001–1023 (2013).

Hall-Beyer, M. Patterns in the yearly trajectory of standard deviation of NDVI over 25 years for forest, grasslands and croplands across ecological gradients in Alberta, Canada. Int. J. Remote Sens. 33, 2725–2746 (2012).

Curran, P. J. The semivariogram in remote sensing: An introduction. Remote Sens. Environ. 24, 493–507 (1988).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python (2011).

Bueno, I. et al. RapidFEM4D: aboveground biomass density maps for post-Hurricane Ian forest monitoring in Florida. at https://doi.org/10.15482/USDA.ADC/28304213.v1 (2025).

Chojnacky, D. C., Heath, L. S. & Jenkins, J. C. Updated generalized biomass equations for North American tree species. Forestry 87, 129–151 (2014).

Gonzalez-Benecke, C. A. et al. Local and general above-stump biomass functions for loblolly pine and slash pine trees. For. Ecol. Manage. 334, 254–276 (2014).

Gonzalez-Benecke, C. et al. Local and General Above-Ground Biomass Functions for Pinus palustris Trees. Forests 9, 310 (2018).

Mitsch, W. J. & Ewel, K. C. Comparative biomass and growth of cypress in Florida wetlands. Am. Midl. Nat. 417, 426 (1979).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the intramural research program of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Rapid Response to Extreme Weather Events Across Food and Agricultural Systems (Grant # 2023-68016-39039). Carlos A. Silva has been funded through U.S. National Science Foundation (Grant # 2409886) and NASA’s grants (ICESat-2, 80NSSC23K0941), Carbon Monitoring System (CMS, grant 80NSSC23K1257), and Commercial Smallsat Data Scientific Analysis (CSDSA, grant 80NSSC24K0055). We would like to thank the School of Forest, Fisheries, and Geomatics Sciences and the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) for providing access to the FAS Millhopper Unit and Austin Cary Forest areas. We also extend our gratitude to the personnel responsible for the Myakka State Forest and Okaloacoochee Slough State Forest for their cooperation and support. The findings and conclusions in this publication are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: I.T.B., C.A.S; Methodology: I.T.B., M.B.S., M.A.K; Software: I.T.B, C.H; Validation: I.T.B.; Formal analysis: I.T.B.; Investigation: I.T.B.; Resources: C.A.S.; Data curation: I.T.B., C.A.S., M.B.S, J.X.; Writing – Original Draft: I.T.B.; Writing – Review and editing: I.T.B., C.A.S, V.M.D, A.S., J.Q., J.X., K.B., J.W.A., D.R.V., J.V., A.S., C.K.; Visualization: I.T.B., Supervision: C.A.S.; Project administration: C.A.S.; Funding acquisition: C.A.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bueno, I.T., Silva, C.A., Hamamura, C. et al. Aboveground biomass density maps for post-hurricane Ian forest monitoring in Florida. Sci Data 12, 1189 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05464-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05464-0

This article is cited by

-

Synergistic use of ICESat-2 lidar data and Sentinel-2 imagery for assessing hurricane-driven forest changes

Environmental Monitoring and Assessment (2025)