Abstract

The Small snakehead (Channa asiatica) is an economically important species in both aquaculture and ornamental trade, mainly distributed in South China and Southeast Asia. Despite its significance, limited genomic resources have impeded in-depth genetic studies and breeding programs. In this study, we used PacBio HiFi long-read sequencing, Illumina short-read sequencing, and Hi-C technologies to generate a high-quality chromosome-level genome of the C. asiatica. The final genome spans 659.44 Mb, with an impressive 98.18% anchored to 23 chromosomes. Notably, the contig N50 and scaffold N50 are 23.92 Mb and 29.61 Mb, validated by a BUSCO completeness score of 98.93%. Genome annotation identified 26,603 protein-coding genes, 99.29% of which were confirmed by BUSCO analysis, and 93.68% were functionally annotated. Approximately 27.72% of the genome sequences were classified as repeat elements. This high-fidelity genome assembly provides a robust foundation for advancing molecular breeding, comparative genomics, and evolutionary studies of C. asiatica and related species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The Small snakehead (Channa asiatica, Channidae) is a fish with significant culinary and ornamental value, highly favoured by both aquaculture farmers and fish enthusiasts1,2. This species is primarily distributed across Southeast Asia and the regions south of the Yangtze River in China. The Small snakehead is particularly noted for the striking appearance of its body surface, which is characterized by distinctive stripes and silver-white spots3. The Small snakehead is known for its strong vitality, fast growth rate, and ability to reach market size within the first year of cultivation. It is highly favoured by farmers and consumers for its abundant meat, few bones, and delicious taste4. Additionally, due to its small size, surface features colourful stripes and white spots, making it highly ornamental and popular among native fish enthusiasts who keep it in aquariums. Small snakehead has strong environmental adaptability and can use its gill rakers to breathe air, which facilitates high-density intensive cultivation and live fish transportation5.

Previous research on Small snakehead has primarily focused on mitochondrial sequences, colour variation, ecology, physiology, and toxicology6,7,8. The complete mitochondrial DNA sequence of Small snakehead has been determined, revealing a genome size of 16,550 base pairs, which provides essential genetic information for molecular identification6. Whole-genome resequencing has also identified a nonsense mutation in the csf1ra gene associated with the white phenotype, which affects pigmentation and sheds light on the genetic basis of albinism in this species3. Recent studies have extensively explored the molecular mechanisms and environmental adaptability of Small snakehead, particularly its responses to hexavalent chromium (Cr6+)7. These findings offer crucial insights for reproduction and molecular breeding programs in Small snakehead cultivation. Despite the ecological and economic significance of this species, genomic data on this species remain relatively limited. To date, the chromosomal genomes of several species within the Channa genus have been sequenced, including C. argus and C. maculata9,10. Additionally, the mitochondrial genomes of C. siamensis, C. burmanica, and C. aurantimaculata have been determined, providing further insights into the genetic diversity of the Channa genus11,12.

In this study, we used PacBio HiFi long-read sequencing, Illumina short-read sequencing, and Hi-C technologies to generate a high-quality chromosome-level genome of the C. asiatica. The development of this reference genome is expected to significantly advance population genetics and facilitate the identification of functional genes linked to key economic traits in the Small snakehead. This genomic resource provides a solid foundation for advancing molecular breeding and gene editing applications in this species.

Methods

Sample collection and DNA extraction

A mature male C. asiatica specimen was collected from the Pearl River (Guangzhou, China). Muscle tissue from this specimen was used to extract DNA for whole-genome sequencing, which included Illumina short-read sequencing, PacBio HiFi long-read sequencing, and Hi-C sequencing. Genomic DNA was isolated from muscle tissue with the Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA quality was evaluated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and concentrations were measured with a NanoDrop One spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). All procedures strictly followed the guidelines approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pearl River Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences (Approval No. PRFRI-2024-012).

Genome sequencing

For short-read sequencing, a 350 bp paired-end library was constructed using the Illumina TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Kit and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, CA, USA), yielding 56.47 Gb (84.27x) of paired-end raw sequence data (Table 1). Long-read sequencing was performed using the PacBio Sequel II system with a SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 (Pacific Biosciences, USA). A total of 38.74 Gb of continuous long reads (HiFi) with an average length of 15.96 kb were generated (Table 1). Hi-C library construction involved dissection of approximately 1 g muscle tissue, followed by in situ chromatin proximity ligation using the DpnII restriction enzyme according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Arima Genomics, USA). The resulting Hi-C library was sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, producing 101.46 Gb (149.54x) of raw Hi-C reads (Table 1).

RNA extraction and transcriptome sequencing

Total RNA was isolated from ten tissues (muscle, liver, spleen, kidney, intestine, heart, brain, swim bladder, testis) using TRIzol reagent. RNA integrity was verified via an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer. Equal quantities of high-quality RNA from each tissue were pooled to construct a strand-specific cDNA library using the TruSeq RNA Library Prep Kit v2 (Illumina, CA, USA). The library was sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, CA, USA), yielding 22.64 Gb of transcriptomic data for genome annotation (Table 1).

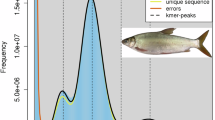

Genome size and heterozygosity estimation

To estimate the genome size of the C. asiatica, a k-mer analysis was conducted using Illumina clean reads. First, Jellyfish (v2.3.0)13 was employed to calculate the frequency of 17-mers and generate the k-mer frequency table. Subsequently, GenomeScope (v2.0)14 was used to analyze the k-mer frequency table, yielding a total genome size of 622,512,009 bp, with a heterozygosity rate of 0.379% and 65% unique sequences (Fig. 1).

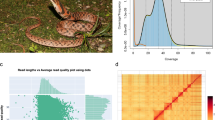

Genome assembly

The genome was de novo assembled using Hifiasm v0.19.515 with default parameters. This process generated 60 contigs with a total length of 659.44 Mb, featuring a maximum contig size of 47.37 Mb and an N50 of 23.92 Mb (Table 2). For chromosome-scale scaffolding, a hybrid approach combining Juicer v1.616 and 3D-DNA v20100817 was implemented. The workflow initiated with BWA v0.7.1718 indexing of the contig-level genome, followed by Juicer processing to identify restriction enzyme cutting sites. Clean Hi-C paired-end reads were then mapped to the contigs using Juicer, and 3D-DNA was applied following standard protocols to generate the initial chromosome assembly. Manual curation was performed using Juicerbox v1.11.0819 to refine chromosome boundaries and correct scaffold misassemblies, resulting in 23 resolved chromosomes (Figs. 2, 3). The revised output from Juicebox was reprocessed through 3D-DNA for per-chromosome scaffolding. The final assembly consisted of 103 scaffolds with a maximum size of 47.37 Mb and an N50 of 29.61 Mb (Tables 2, 3).

Repeat annotation

Given the biological significance of tandem repeats, a genome-wide survey was performed using GMATA v2.2.120 and Tandem Repeats Finder (TRF) v4.10.021 with default parameters. GMATA was specifically applied to detect simple sequence repeats (SSRs) with short repeat units, while TRF was used to identify all classes of tandem repeats. For dispersed repetitive sequences, the workflow initiated with MITE-hunter22 to detect miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs), generating a MITE library file. The genome was then masked using a hard-masking approach (converting repeats to “N”), followed by de novo repeat discovery with RepeatModeler23 to construct a RepMod.lib library. Given the presence of unclassified elements in RepMod.lib, these sequences were subsequently classified using TEclass v2.424. A comprehensive repeat library was created by integrating MITE.lib, RepMod.lib, and Repbase25. This combined library was used to annotate repetitive sequences across the entire genome with RepeatMasker26.

The annotation results revealed that dispersed repeats accounted for 25.29% of the genome (Table 4). Among transposable elements (TEs), DNA transposons were the most abundant class (7.01%), followed by long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs, 4.34%), long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons (2.15%), and short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs, 0.84%). Collectively, repetitive sequences spanned 182,862,722 bp, representing 27.72% of the total genome length (Table 4).

Gene prediction and function annotation

Gene annotation was performed using a three-tiered evidence integration pipeline, incorporating transcriptomic evidence, homologous protein evidence, and ab initio predictions. Transcriptomic evidence was obtained by aligning Illumina RNA-seq reads to the genome assembly with HISAT2 v2.2.127, followed by transcript assembly using StringTie v2.2.328. Putative coding sequences (CDS) were identified with TransDecoder v5.7.129 using default parameters. Homology-based annotation was carried out using protein sequences from five evolutionarily conserved species. Protein-to-genome alignments were conducted with miniprot30. For ab initio prediction, braker v2.1.5 was used to perform gene predictions employing Augustus v3.5.0 and GeneMark-ETP v131 based on reference proteins from the OrthoDB v12 database32. The three evidence streams were consolidated using EVidenceModeler v2.1.0, yielding 26,603 high-confidence protein-coding genes, with an average gene length of 20,822.68 bp, an average coding sequence length of 1,675.78 bp, and an average of 10.08 exons per gene (Table 5).

The functional annotation of predicted protein sequences was performed using Diamond v2.1.1033 against the SwissProt34, KEGG35, KOG36, GO37 and NR38 databases with an e-value cut-off of 1e-5. A total of 25,133 genes were annotated, which accounted for 94.47% of all inferred genes (Fig. 4 and Table 5).

Genome synteny analysis

To compare the whole genome synteny, four chromosome-level genomes of Oryzias latipes, Anabas testudineus, Channa argus and Channa maculata were aligned to the genome assembly of C. asiatica using MCscan (v0.8)39, and syntenic relationships were plotted using the JCVI (v1.1.12)40. Collinearity analysis revealed significant chromosomal collinearity between C. asiatica and the other four bony fish species, although numerous chromosomal rearrangements were also observed (Fig. 5).

Data Records

The raw sequencing reads of all libraries have been deposited into NCBI SRA database via the accession number PRJNA113901141. The assembled genome has been deposited at Genbank under the accession number GCA_041146785.142. Moreover, the genome annotations, predicted coding sequences and protein sequences are available at Figshare43.

Technical Validation

Assessment of genome assembly

The accuracy of the Small snakehead genome assembly was evaluated by assessing its completeness using the conserved metazoan gene set ‘actinopterygii_odb10’ from BUSCO (v5.4.3)44. The analysis demonstrated high completeness, with an overall completeness of 98.93%. Specifically, 98.24% of the genes were complete and single-copy, 0.69% were complete and duplicated, 0.35% were fragmented, and 0.71% were missing. These findings indicate the high quality of the Small snakehead genome assembly (Table 6). To evaluate the quality of the genome assembly, we calculated the mapping rates of both PacBio HiFi and Illumina reads against the assembled genome. Illumina short reads were aligned using BWA (v0.7.17-r1188), while HiFi reads were mapped with Minimap2 (v2.24). A total of 99.58% of Illumina reads and 99.75% of PacBio HiFi reads successfully aligned to the reference genome, indicating high assembly accuracy and completeness.

Gene annotation validation

To evaluate the integrity of the annotated gene set, we conducted BUSCO44 analysis using conserved single-copy homologous genes from the ‘actinopterygii_odb10’ library. The results revealed that approximately 99.29% of the complete gene elements are present in the annotated gene set, indicating a high level of completeness in the conserved gene predictions. Specifically, 98.35% of the genes were complete and single-copy BUSCOs, with only 0.93% fragmented and 0.63% missing from the assembly (Table 7). These findings highlight the exceptional integrity and conservation of gene content in the Small snakehead genome assembly, leading to highly confident prediction outcomes.

Code availability

No special codes or scripts were used in this work, and date processing was carried out based on the protocols and manuals of the corresponding bioinformatics software. The version and parameters of software have been described in Methods.

References

Froese, R. & Pauly, D. (Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia Los Baños, Philippines, 2010).

Yu, Z. et al. Bioflocs attenuate Mn-induced bioaccumulation, immunotoxic and oxidative stress via inhibiting GR-NF-κB signalling pathway in Channa asiatica. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 247, 109060 (2021).

Yuan, D. et al. Whole genome resequencing reveals the genetic basis of albino phenotype in an ornamental fish, Channa asiatica. Aquaculture Reports 36, 102193 (2024).

Zhao, L. et al. Polysaccharide from dandelion enriched nutritional composition, antioxidant capacity, and inhibited bioaccumulation and inflammation in Channa asiatica under hexavalent chromium exposure. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 201, 557–568 (2022).

Chew, S. F., Wong, M. Y., Tam, W. L. & Ip, Y. K. The snakehead Channa asiatica accumulates alanine during aerial exposure, but is incapable of sustaining locomotory activities on land through partial amino acid catabolism. Journal of experimental biology 206, 693–704 (2003).

Meng, Y. & Zhang, Y. Complete sequence and characterization of mitochondrial DNA genome of Channa asiatica (Perciformes: Channidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part A 27, 1271–1272 (2016).

Yu, Z. et al. Toxic effects of hexavalent chromium (Cr6+) on bioaccumulation, apoptosis, oxidative damage and inflammatory response in Channa asiatica. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 87, 103725 (2021).

Zhu, S.-R., Fu, J.-J., Wang, Q. & Li, J.-L. Identification of Channa species using the partial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene as a DNA barcoding marker. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 51, 117–122 (2013).

Ou, M. et al. Chromosome-level genome assemblies of Channa argus and Channa maculata and comparative analysis of their temperature adaptability. GigaScience 10, giab070 (2021).

Zhou, C. et al. Chromosome-scale assembly and characterization of the albino northern snakehead, Channa argus var.(Teleostei: Channidae) genome. Frontiers in Marine Science 9, 839225 (2022).

Li, R. et al. Complete mitochondrial genome of a kind of snakehead fish Channa siamensis and its phylogenetic consideration. Genes & genomics 41, 147–157 (2019).

Xu, T. et al. The Complete Mitogenomes of Two Species of Snakehead Fish (Perciformes: Channidae): Genome Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis. Diversity 16, 346 (2024).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770 (2011).

Ranallo-Benavidez, T. R., Jaron, K. S. & Schatz, M. C. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat Commun 11, 1432 (2020).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat Methods 18, 170–175 (2021).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell systems 3, 95–98 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95 (2017).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell systems 3, 99–101 (2016).

Wang, X. & Wang, L. GMATA: an integrated software package for genome-scale SSR mining, marker development and viewing. Frontiers in plant science 7, 215951 (2016).

Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 27, 573–580 (1999).

Han, Y. & Wessler, S. R. MITE-Hunter: a program for discovering miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements from genomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 38, e199–e199 (2010).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 9451–9457 (2020).

Abrusán, G., Grundmann, N., DeMester, L. & Makalowski, W. TEclass—a tool for automated classification of unknown eukaryotic transposable elements. Bioinformatics 25, 1329–1330 (2009).

Jurka, J. et al. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenetic and genome research 110, 462–467 (2005).

Chen, N. Using Repeat Masker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Current protocols in bioinformatics 5, 4–10 (2004).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nature biotechnology 37, 907–915 (2019).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nature biotechnology 33, 290–295 (2015).

Haas, B. J. et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nature protocols 8, 1494–1512 (2013).

Li, H. Protein-to-genome alignment with miniprot. Bioinformatics 39, btad014 (2023).

Bruna, T., Lomsadze, A. & Borodovsky, M. GeneMark-ETP: automatic gene finding in eukaryotic genomes in consistency with extrinsic data. BioRxiv, 2023-2001 (2023).

Kuznetsov, D. et al. OrthoDB v11: annotation of orthologs in the widest sampling of organismal diversity. Nucleic Acids Res 51, D445–D451 (2023).

Buchfink, B., Reuter, K. & Drost, H.-G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat Methods 18, 366–368 (2021).

Bairoch, A. & Apweiler, R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence database and its supplement TrEMBL in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res 28, 45–48 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 28, 27–30 (2000).

Tatusov, R. L. et al. The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC bioinformatics 4, 1–14 (2003).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 25, 25–29 (2000).

Kanz, C. et al. The EMBL nucleotide sequence database. Nucleic Acids Res 33, D29–D33 (2005).

Tang, H. et al. Synteny and collinearity in plant genomes. Science 320, 486–488 (2008).

Tang, H. et al. JCVI: A versatile toolkit for comparative genomics analysis. iMeta, e211 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive. https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP547255 (2024).

NCBI Genbank. https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_041146785.1 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the Small snakehead (Channa asiatica) using PacBio HiFi and Hi-C sequencing. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24746397 (2024).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-46); Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, CAFS (2023TD37, 2025SJHX1, 2025XK01); China-ASEAN Maritime Cooperation Fund (CAMC-2018F); Guangdong Province Rural Revitalization Strategy Special Fund (2023-SJS-00-001); the Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (2024A1515030165); National Freshwater Genetic Resource Center (FGRC18537); Guangdong Rural Revitalization Strategy Special Provincial Organization and Implementation Project Funds (2022-SBH-00-001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, H., Liu, J., Cui, T. et al. A chromosome-level reference genome assembly of the Small snakehead (Channa asiatica). Sci Data 12, 1159 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05479-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05479-7